ABSTRACT

Australian social workers are routinely employed in forensic roles, including forensic medicine, domestic and family violence, youth justice, probation or parole, and correctional work. Forensic social work often is considered to be a specialist area of social work due to the required additional knowledge of the law, crime, victimology, comorbidity, and intersectionality. Globally, and in Australia, concerns have been raised about the training and education of forensic social workers. In Australia, there is no clear forensic social work education pathway; there are no tertiary forensic social work courses, and the AASW does not recognise forensics in their credentialing program. Thus, practitioners are seen to qualify through their generic studies. The purpose of this study was to ascertain the extent to which forensic knowledge features in the current AASW accredited undergraduate social work programs. A content analysis of available 2023 Bachelor of Social Work programs was undertaken to reveal any disparity of forensic offerings under a generic qualification. This research is positioned within the wider “generic practice versus specialisation” debate in Australian social work education. It raises concerns about the fragmented nature of forensic studies within Australian social work education.

There is a lack of clarity around what constitutes useful and sufficient forensic studies within Australian social work education, in the absence of specialist programs.

There is little opportunity for social work students to gain “social work specific” forensic training in their qualifying education.

Further consideration of a specialist forensic social work pathway could assist with the advanced training of this workforce.

IMPLICATIONS

There have been references to social workers working within and alongside the Australian criminal justice system for over a century. From as early as 1911, social work guidelines featured offender reformation as part of their role (Lawrence, Citation2016). Since then, Australian social workers have occupied roles in correctional settings; re-entry, reintegration, and rehabilitation programs; youth justice; forensic mental health; and substance misuse programs (Duvnjak et al., Citation2022). Historically, forensic work (specifically probation and parole work) has played an essential role in Australian social work's national recognition and professionalisation (Lawrence, Citation2016). The term “forensic social work” emerged in Australian social work research in 1965 with calls for its recognition as a specialist field of practice (Benjamin & Settle, Citation1965). Since then this argument has re-emerged several times (Green et al., Citation2005; Sheehan, Citation2012, Citation2016). At present, “forensics” is not a recognised specialisation in social work in Australia: this means there is no clear education or training pathway, no professional competencies or standards, no forensic specialist credential offered through the Australian Association of Social Work (AASW), and no independent professional forensic social work association. Nevertheless, contemporary Australian social workers continue to occupy a wide range of forensic roles around Australia, including within community legal centres, forensic medical and coroner services, correctional facilities, forensic disability services, and forensic mental health services. Australian forensic social work is a diverse field of practice, where practitioners are united through their shared experience of working within or in conjunction with oppressive and ethically contentious structures and systems (Sheehan, Citation2016; Jarldorn, Citation2020).

Forensic social work is often given the rudimentary definition of social work within a forensic or legal context (Harvey, Citation2020). However, this definition does not capture the unique and ethically challenging nature of this field of practice. Interestingly, the history of forensic psychology shows a parallel in limited conception. Before the 1990s, it was largely framed as clinical psychology within a legal setting (Bartol & Bartol, Citation2013). However, this framing has now been expanded into the more comprehensive account seen today. Forensic psychology represents a research endeavour and professional practice, and, as a specialisation, it both produces its own psychological knowledge and applies that psychological knowledge to justice systems (Bartol & Bartol, Citation2013). Reduced conceptualisations are often the effect of being born a subset of a discipline or practice, but as their research body grows, so does their legitimacy as a specialist practice. This article is working from the remit of forensic social work as the practice applicable across criminal justice and legal systems, requiring an understanding of the law, criminality, intersectionality, power, oppression, and mental health, and the skills to maintain a social justice orientation within an often hostile and involuntary environment (Harvey, Citation2020; Maschi et al., Citation2017; NOFSW, Citation2020; Sheehan, Citation2016).

Social workers bring an important and meaningful perspective to the forensic field. Australian forensic social work often exists within a multidisciplinary team that comprises legal or medical professionals, other mental health clinicians and other discipline-trained professionals (Harvey, Citation2020; Sheehan, Citation2016; Turner, Citation2022). As social justice advocates, forensic social work interventions focus on the individual’s cycle of disadvantage and on the system’s production of disadvantage (Maschi et al., Citation2019). They operate at a macrolevel, as advocates for institutional culture and policy change, and at a microlevel, as direct practitioners (Maschi & Killian, Citation2011). Australian social workers have been crucial in enabling systemic changes for vulnerable populations, such as advocating for legal reforms for youth, women, and aged offenders (Sheehan, Citation2012). At an organisational level, social workers identify gaps in service provision and develop programs to rectify identified gaps (O'Donahoo & Simmonds, Citation2016). At an individual level, they provide psychosocial interventions, including assessing and managing risk, and engaging with clients, families, and communities (Turner, Citation2022). At all levels, forensic social workers must navigate the spaces of imbalance between clients, other specialists, and legal professionals; they operate as a vehicle for knowledge to be circulated between the parties (Naessens & Raeymaeckers, Citation2020; Ratliff & Beyer, Citation2019). This can take the form of an expert witness, case manager, report writer, restorative justice convenor, or community policy consultation.

Forensic social work requires practitioners who have the training and skills to support clients with a wide range of vulnerabilities and needs, and are able to practice within ethically tense, bureaucratic, and often politically hostile organisational contexts (Schaffer, Citation2021). In the United States of America, forensic-specialised social work education has been shown to be instrumental in creating critical practitioners who are attentive to the human rights and social justice issues present in a forensic context (Kheibari et al., Citation2021; Maschi et al., Citation2019; Robbins et al., Citation2014). A key component of these educational programs is that students are given opportunities to critically reflect on their own biases, beliefs, and attitudes towards offending, complex behaviour, and controversial issues relating to forensics (Maschi et al., Citation2019). There are no official Australian forensic social work education or training programs, or any practice competencies or standards to outline the skills and knowledge needed for this specialisation (Ogloff & Sheehan, Citation2014). Several researchers, however, have identified some of the skills and knowledge needed for Australian forensic social work. Green et al. (Citation2005) suggested that forensic social workers require expertise and specialised skills related to their mandatory forensic professional duties, such as working with involuntary clients, report writing, and cross-examination. Sheehan (Citation2016) suggested a need to have the generalist core skills and values of social work retaught in relation to the forensic sphere, as they can be constrained and complicated by the pressures of a forensic context. For O'Donahoo and Simmonds (Citation2016), forensic social workers need to be adaptive in their practice and advocate against dominant ideologies in order to shift the focus and trajectory for the client: for example, promoting the psychosocial recovery model within an otherwise biomedical-dominated space. In forensic mental health, Turner (Citation2022) suggested that the social worker must understand and help the client navigate the justice systems, supporting the client, families or carers through the gaps and transitions between systems, such as supporting someone going from an institution into community care (Turner, Citation2022). The duties of the practitioner include managing interagency communication and connecting clients and their families with resources and local services. The practice of the Australian forensic social worker is underpinned by systems theory; person-in-context approaches; strengths-based, biopsychosocial assessments; and recovery-orientated practice (Green et al., Citation2005; Harvey, Citation2020; O'Donahoo & Simmonds, Citation2016; Turner, Citation2022).

Forensic Landscapes in Australia

Forensic social workers support some of the most vulnerable and often high-risk populations, with responsibilities during investigation, mitigation, incarceration, and the probation and parole period (Harvey, Citation2020; Sheehan, Citation2016). These responsibilities are framed within increasing societal demand for the prediction and mitigation of risk, particularly with regard to recidivism and adverse circumstances, including harm to or death of a child (Sheehan, Citation2014). Social workers can advocate for a more nuanced understanding of risk, including a shift from criminality as a moral failing to an awareness of the environmental and psychological explanations for crime. For example, a significant number of people who commit crimes also have their own histories as a victim of violence and trauma (Turner, Citation2022). It is the practitioner’s duty to ensure a voice is given to the trauma, historical, developmental, and psychosocial factors that contribute to criminal behaviour (Ratliff & Beyer, Citation2019). Recent Australian statistics show that imprisonment rates are rising (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021), and the majority of first-time offenders have comorbid and intersecting issues, including substance misuse, mental health issues, and poverty. Data from the latest 2021 National Prisoner Health Data Collection (NPHDC) revealed that prison entrants evidence a myriad of social disadvantages: 33% hold a Year 9 or lower education level, 65% have used an illicit substance in the last year, 40% have had mental health issues, 25% are currently taking mental health-related medication, and 21% report a history of self-harm (AIHW, Citation2021). In addition, harsher sentences and outcomes are more common for oppressed and disadvantaged communities, evidenced by the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in prisons (Dawes, Citation2016; Jarldorn, Citation2020).

Forensic clients often are situated within a system that is in part an exacerbation of disadvantage (Harvey, Citation2020; Jarldorn, Citation2020; Sheehan, Citation2012). After engaging with the criminal justice system, individuals are more likely to experience new and compounding forms of disadvantage, including homelessness, health issues, and social exclusion. Their reintegration into society is fraught with oppressive social stigmas (Duvnjak et al., Citation2022). Thus, their experience with the criminal justice system adds to their criminogenic needs rather than leading to rehabilitation or behavioural change. Like most western nations, Australia has faced an ongoing assault from neoliberalism (Baffour et al., Citation2020; Jarldorn, Citation2020; Schaffer, Citation2021). Neoliberalism fosters an individualised and deviancy-based view of crime and offending; hence, recidivism is seen as the individual’s failing (Jarldorn, Citation2020). Reincarceration or recidivism is a primary driver in rising incarceration rates (ABS, Citation2021). The 2022 Australian Report on Government Services (Australian Government Productivity Commission, Citation2022) noted that over half (53.1%) of released prisoners had returned to corrective services within two years. Under a traditional recidivism perspective, reincarceration is a failure because incarceration has not achieved the goal of deterring future criminal behaviour. Research on reoffending and recidivism shows that this issue is not easily solved (Fitzgerald et al., Citation2016; Payne, Citation2007). Individual and social factors, including gender, unemployment, family issues, relationship status, education, geographical location, homelessness, mental health issues, and substance misuse each play a role. The forensic social worker’s interventions recognise a holistic and systemic view of crime, and should recognise, respond, and attempt to reduce the situational and structural barriers faced by the forensic population (Loue, Citation2018; Ratliff & Beyer, Citation2019).

Forensic Social Work as a Specialisation

At present, there is yet to be a consensus on what Australian forensic social work is. A number of researchers have called for forensic social work to be considered a specialist field (Green et al., Citation2005; Sheehan, Citation2012, Citation2016). Specialisation within a profession refers to dedicated education and training pathways that equip students with specific knowledge and skills required for a domain of practice. Blom (Citation2004) classified social work specialisation by its category requirements of field, setting, age, problem, methods, function and task. In comparison, generic practice is a toolset for all practitioners: it paints a multimethod, broadly humanistic brushstroke. Blom (Citation2004) conceived of generic social work knowledge, both taught and applied, as generalised concepts and methods universally applied to its range of settings and clients. Forensic social work as a specialisation in Australia exists as two possibilities, as a distinct specialist practice model and as the application of generalist skills within a specialist setting.

The recognition of a distinct specialist practice model carries an acknowledgement of the advanced skills and knowledge required (Sheehan, Citation2014). The legal and statutory constraints and obligations of forensic social workers place additional requirements on practitioners, meaning they must have a greater familiarity with the law than their generalist counterparts (Green et al., Citation2005; Sheehan, Citation2012, Citation2016). In addition, the practitioner’s knowledge of victimology, offending, criminality, and the justice model is seen to go beyond generic social work (Green et al., Citation2005; Sheehan, Citation2016). In comparison, forensic social work as the application of generalist skills within a specialist setting recognises that generalist core practices and skills taught in Australian social work education make them effective practitioners in the criminal justice space: these skills include critical reflection, empathy, self-awareness, ethical reasoning, and decision making (Stout, Citation2017). This notion was reflected in Naessens and Raeymaeckers’s (Citation2020) research, which highlighted the importance of a generalist practice ethos in forensic practice. These authors identified that forensic populations are a diverse cohort with varying concurrent issues, so the broad scope of generic social work practice is still needed. They focus on the role of the social worker as a conduit to other specialist services. Generalist social work here maintains a holistic and person-in-context framework while balancing the client’s engagement with other specialist services.

Australian social work education is based on a generic practice model, specifically qualifying tertiary courses. At present, the singular unifying education experience of Australian forensic social workers is their qualifying program. The adequacy of this for forensic training was challenged by the abovementioned research by Sheehan (Citation2016), where a number of experienced forensic social workers reflected on their generic skills. Sheehan’s (Citation2016) research suggested the need for additional postgraduate courses in Australia to supplement the generic Bachelor of Social Work degree.

Qualifying Bachelor of Social Work

Australian qualifying education is regulated through the Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS) (AASW, Citation2020a). ASWEAS mandates course length, duration, and some content. Forensic social work is not explicitly mentioned in ASWEAS. However, a meaningful grasp of the cultural and psychosocial ramifications of power, oppression, abuse, human development, and mental health would entail some knowledge of the complexities seen in forensic scholarship and practice, and social workers could use this knowledge in reports, referrals and support plans (Harvey, Citation2020; Maschi et al., Citation2019; Turner, Citation2022). Given that there is no explicit expectation to teach forensic content, it is unclear if forensic social work theory and practice competencies are included as a graduate outcome in accredited Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) and Bachelor of Social Work Honours (BSWH) programs.

In recent decades, the AASW has come under pressure to include certain issues or methods, most notably with family violence content (Cooper, Citation2007; Crisp, Citation2019). Prescriptive accreditation does not align with the generic practice history of the AASW accreditation. Indeed, any dictated social work curriculum can have problems: these include concerns about stagnant content, and social work academics losing their creativity and autonomy (Crisp, Citation2019; Healy, Citation2019). The premise of generic undergraduate social work is to leave space for teachers and students to explore their research and curricula interests. Fook (Citation2003) noted that within an undergraduate generalist social work course, students have the opportunity to use electives and field education to explore their interests in specialised fields, but that specialisation in Australian social work education happened primarily in postgraduate study and research.

Is the current allowance for specialisation enough? This article asks this question in the context of a broader exploration to ascertain if Australian social work graduates are adequately prepared for practice in forensic settings. Thus, a review of accredited BSW and BSWH programs was undertaken to assess what kind of units of study, core and elective, are currently available for students interested in the area of forensics. The guiding research questions are how many forensic-related courses are available to students across the AASW accredited BSW and BSWH programs and how do the different BSW and BSWH program structures restrict or open student access to forensic courses?

Methodology

Review of Social Work Programs

Research Design

To address the study’s research questions, the authors conducted a content analysis of the published course structures of available 2023 Bachelor of Social Work programs accredited by AASW. Content analysis is drawn on because it allows a structured research technique involving the systemic and purposive reading of texts and other data to make replicable and valid inferences (Drisko & Maschi, Citation2015; Krippendorff, Citation2019). A priori codes were set by pre-existing categories outlined in sample course structures: for example, unit names, unit descriptors, and faculty locality.

Sample Collection

This study drew its data from the websites of Australian universities with AASW accredited undergraduate social work programs (AASW, Citation2014). AASW accredited BSW and BSWH programs have a unique course structure with a mixture of mandatory core courses, restricted electives (e.g., a specific list of courses to choose), and free electives (e.g., any university-wide course). The authors reviewed the 2023 course structures of AASW accredited BSW and BSWH programs listed on the AASW webpage (n = 25). Institutions with provisional acceptance were excluded from the study, as were Master of Social Work Qualifying (MSWQ) programs.

Data Analysis

Data was gathered from each institution’s 2023 sample course structure. Units of study offered in the BSW and BSWH course structures were coded into 2 categories: 1 = forensic focused and 0 = nonforensic courses. Forensic-focused courses were defined as subjects where the majority of the course content was related to issues within and associated with the justice system(s), including crime, offending, victims, judicial settings, and other related issues where forensic content was the primary learning outcome. Nonforensic courses were defined as subjects with either no mention of forensic content, or some mention, where the forensic content did not feature as a primary learning outcome.

Findings

The study findings revealed that none of the programs offered a specific forensic social work course. The majority (88%, n = 22) of programs included one core course specific to law and social work. One program framed its law course as “Socio-Legal Practice in Social Work Settings”; this course appeared to be the closest equivalent to forensic social work. Nearly half (48%) of the programs had a forensic-focused course in their core requirements: 11 programs (44%) included one course, and one program had two courses. Of these 13 courses, four were about general violence (structural, interpersonal, and family), four were specific to domestic and family violence, one was specific to child abuse, three were about working within a forensic statutory body (Juvenile Justice and Child Protection), and one was about general crime and deviancy theory. Of the nine courses relating to violence, child abuse, and family violence, only five were specific to social work. Of the three courses relating to working within a forensic statutory body (Juvenile Justice and Child Protection), none noted social work in their learning outcomes or descriptions, there were no social work specific prerequisites, and only one of the three was co-ordinated by a social work qualified academic. The nonprofession specific design was likely to include students from other degrees such as humanities, criminology, and psychology. Thus, of the 13 forensic-focused core courses, only five were social work specific across all AASW accredited BSW and BSWH programs reviewed.

Electives were included in 84% of the BSW and BSWH programs (n = 21). Institutions offered between one to five elective courses, with 36% offering 2 electives. The majority of programs (68%) allowed for social work students to undertake a forensic-related elective, but 16% had restricted electives with no forensic specific option, and 16% did not include electives in their course structure. Forensic-focused courses were predominantly from criminology, although some psychology, sociology, and other humanities subjects were also available. Only 12% of programs (n = 3) did not include a forensic-focused core course or a forensic elective option.

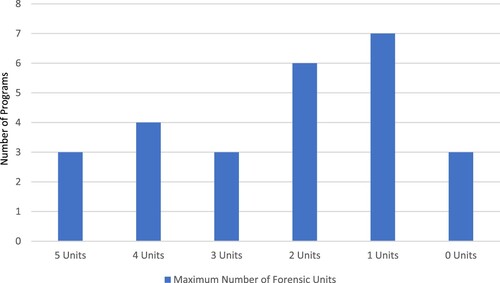

The study findings revealed that course structure affects access to forensic units. The researchers explored the possible maximum number of forensic courses available for students to take. As shown in , the majority of programs (64%) allowed students a maximum of two opportunities to study forensic content. Course structures without electives had the least opportunity to study forensic content, but courses with more free electives had the greatest opportunities. Nearly 30% of programs (n = 7) had four or more opportunities to undertake forensic courses.

Two (8%) accredited BSW or BSWH programs could be undertaken as a dual degree: the Bachelor of Social Work and the Bachelor of Criminology or Criminal Justice. These programs are five years in duration; their program structure follows the core and elective courses from the individual degrees. This equates to 15 courses in criminology and justice studies. There are no elective options to study outside of social work and criminology, and no additional social work courses are offered in these programs that are not available to single-degree BSW or BSWH students.

Discussion

Of the courses reviewed in this study, most undergraduate social work students have an opportunity to learn some legal and forensic content during the course of their studies. Although this may seem positive from an initial glance, upon closer inspection these opportunities have a range of limitations. This review found a lack of “social work specific” forensic content and a wide disparity between the opportunities given to study forensic-focused content across BSW and BSWH programs. Most social work students had two or fewer opportunities for forensic study as the maximum they could undertake during their qualifying program. This raises concerns about the ability of a student to fully comprehend the complexity of forensics within these limitations.

The social work specific forensic courses offered to students focused on violence and abuse. This is unsurprising given the previously mentioned ASWEAS learning criteria and AASW’s Family Violence Capability Framework released after the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence (Crisp, Citation2019). These courses all contain a theoretical understanding of violence, power and control, trauma, and policy context. Violence and abuse are important areas of study for social workers, but in relation to forensics, it is only one specific type of crime and does not necessarily give students a comprehensive understanding of crime and working within a forensic setting. In the absence of a distinct forensic social work unit of study, gaps exist where students are offered the space to critically reflect on their beliefs about forensics and the criminal justice system. As shown in forensic social work education internationally, critically reflecting on one’s beliefs and attitudes to crime, offending, and the justice system is essential to developing a holistic practice framework and can ultimately improve practice (Maschi et al., Citation2019). The presence of forensics in Australian social work education relies primarily on offerings from other academic disciplines and nonprofession-specific content. Elective courses mainly come from criminology and sociology; these disciplines traditionally offer a theoretical study of crime, offending, and society. They play an important role in teaching critical theory and thinking, as critical theory encourages students to evaluate power and social structures and foster a social justice perspective (Howes, Citation2017). However, as reflected in existing literature, many students have difficulties bridging the gap and linking critical macrolevel theory to microlevel direct practice skills (Hurley & Taiwo, Citation2019; Tilbury et al., Citation2010). Tilbury et al. (Citation2010) noted that social work educators have an essential role in guiding students through the translation of generic critical theory into social work practice skills. Regarding forensics, Australian social work does not have a clear bridge that links these macrolevel ideas with discernible microlevel skills for deployment. In comparison to international models of forensic social work education (Maschi et al., Citation2019), the Australian model has reduced opportunities to develop forensic-specific practice skills, such as testifying in court, forensic interviewing, and working with other legal professionals.

Given that the BSW and BSWH are generic practice programs, it is unsurprising that forensic content is only found in some program structures. In highlighting these findings, this article aligns with other scholarly criticisms of prescriptive social work curricula and accreditation requirements (Cooper, Citation2007; Crisp, Citation2019; Healy, Citation2019) and is not advocating for forensic training to be mandated in ASWEAS. Instead, it challenges the notion that all generically trained social workers are equally qualified to work in the area of forensics. The authors pinpoint the innate lack of clarity around what constitutes useful and sufficient forensic studies within Australian social work education, in the absence of specialist programs. Despite a lack of consistency in exposure to forensic content, all social work graduates are considered qualified to work with these vulnerable populations. As mentioned in the findings, two institutions offer double degrees, and their program structure includes a much larger forensic component than generic BSW and BSWH programs. However, there needs to be more research into the efficacy of these programs, as the same problem of applying critical theory to social work practice exists.

It has been argued that Australia’s undergraduate social work education does not equip students for forensic practice (Sheehan, Citation2016). Indeed, it is challenging to establish educational expectations and requirements without Australian forensic professional standards or competencies. This study raises questions about the wide disparity of forensic knowledge under the banner of generic BSW and BSWH programs and their inadequacy. There is minimal opportunity for social work students to get social work specific forensic training in their qualifying education. Multidisciplinary theory is currently being positioned as sufficient to equip social workers to understand and work within forensics. These findings suggest that further research is needed to understand, in detail, the gap between generic social work education and the skills and knowledge necessary for ethical and effective Australian forensic social work. Further exploration is required to address the lack of forensic social work education and training pathways revealed in this review.

Limitations

A limitation to this study is its reliance on website material to be current and reliable. This includes the AASW accredited list of institutions, program structures, and handbooks. The researchers did not access course materials and relied on publicly available information. All course structures are subject to change, and most retain a flexibility to be altered if required or requested. Thus, staff changes could open or close possibilities, and a student with enough motivation could study more opportunities than described in this study.

Conclusion

Australia’s tertiary social work education is based on a generic practice model. Such a course structure is designed to facilitate engagement with multiple practice models and fields of practice. Forensic social work is one field of practice. As expected, forensic studies within AASW accredited BSW and BSWH programs varies. Social work specific forensic coursework mainly relates to understanding violence and abuse, and most specific forensic knowledge is taught outside the discipline of social work, most notably through criminology. At present, Australian forensic social work is unrecognised in tertiary education or through any formal credentialing process, meaning that there is no regulation of the study, professional development or training pathways for students or practitioners. Currently, all students with a BSW and BSWH are seen as equally qualified to work with these vulnerable populations. This study raises concerns that the general qualifying degree hides a wide disparity of exposure to forensic knowledge. Further research is needed to understand the professional competencies of an Australian forensic social worker and develop an adequate education model.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2014, February 21). AASW Accredited Programs. https://www.aasw.asn.au/careers-study/accredited-courses

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2020a). Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS). https://www.aasw.asn.au/careers-study/education-standards-accreditation

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021, December 09). Prisoners in Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/prisoners-australia/latest-release

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. (2022). Report on Government Services (Part C, Chapter 7). https://www.pc.gov.au/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2022/justice

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021, September 16). Adult prisoners. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/adult-prisoners

- Baffour, F. D., Chong, M. D., & Francis, A. P. (2020). Recent developments in criminal justice social work in Australia and India: Critically analysing this emerging area of practice. In I. Ponnuswami, & A. P. Francis (Eds.), Social work education, research and practice. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9797-8_17

- Bartol, C. R., & Bartol, A. M. (2013). History of forensic psychology. In I. B. Weiner, & R. K. Otto (Eds.), The handbook of forensic psychology (4th ed.) (pp. 3–34). Wiley.

- Benjamin, E., & Settle, R. (1965). Forensic social work. Australian Social Work, 18(1), 21–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124076508522542

- Blom, B. (2004). Specialization in social work practice effects on interventions in the personal social services. Journal of Social Work, 4(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017304042419

- Cooper, L. (2007). Backing Australia's future: Teaching and learning in social work. Australian Social Work, 60(1), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070601166745

- Crisp, B. (2019). Educating for social work practice in the 2060s. Australian Social Work, 72(2), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1567801

- Dawes, G. (2016). Keeping on country: Doomadgee and Mornington Island recidivism research report. North and West Remote Health. https://nwrh.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Keeping-Country-Report-Complete.pdf

- Drisko, J., & Maschi, T. (2015). Content analysis: Pocket guides to social work research methods. Oxford University Press. 9780190215491.001.0001

- Duvnjak, A., Stewart, V., Young, P., & Turvey, L. (2022). How does lived experience of incarceration impact upon the helping process in social work practice?: A scoping review. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(1), 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa242

- Fitzgerald, R., Cherney, A., & Heybroek, L. (2016). Recidivism among prisoners: Who comes back? Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 530, 1–10. https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/tandi530.pdf

- Fook, J. (2003). Social work research in Australia. Social Work Education, 22(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470309134

- Green, G., Thorpe, J., & Traupmann, M. (2005). The sprawling thicket: Knowledge and specialisation in forensic social work. Australian Social Work, 58(2), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0748.2005.00199.x

- Harvey, S. (2020). Forensic social work. In M. Petrakis’s (Ed.), Social work practice in health. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003117285

- Healy, K. (2019). Regulating for quality social work education: Who owns the curriculum? In M. Connolly, C. Williams, & D. Coffey (Eds.), Strategic leadership in social work education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25052-2_5

- Howes, L. M. (2017). Critical thinking in criminology: Critical reflections on learning and teaching. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(8), 891–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1319810

- Hurley, D., & Taiwo, A. (2019). Critical social work and competency practice: A proposal to bridge theory and practice in the classroom. Social Work Education, 38(2), 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1533544

- Jarldorn, M. (2020). Radically rethinking social work in The criminal (in)justice system in Australia. Affilia, 35(3), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109919866160

- Kheibari, A., Walker, R. J., Clark, J., Victor, G., & Monahan, E. (2021). Forensic social work: Why social work education should change. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(2), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1671257

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

- Lawrence, R. (2016). Professional social work in Australia. Australian National University EView. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/32428/610990.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Loue, S. (2018). Legal issues in social work practice and research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77414-5_6

- Maschi, T., & Killian, M. (2011). The evolution of forensic social work in the United States: Implications for 21st century practice. Journal of Forensic Social Work, 1(1), 8–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/1936928X.2011.541198

- Maschi, T., Leibowitz, G., & Killian, M. L. (2017). Conceptual and historical overview of forensic social work. In T. Maschi, & G. S. Leibowitz (Eds.), Forensic social work: Psychosocial and legal issues across diverse populations and settings (pp. 3–30). Springer Publishing Company.

- Maschi, T., Rees, J., Leibowitz, G., & Bryan, M. (2019). Educating for rights and justice: A content analysis of forensic social work syllabi. Social Work Education, 38(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1508566

- Naessens, L., & Raeymaeckers, P. (2020). A generalist approach to forensic social work: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Social Work, 20(4), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017319826740

- NOFSW. (2020). National organization of forensic social work specialty guidelines for values and ethics. https://www.nofsw.org/_files/ugd/f468b9_20e60b0830ed4a51808154902b7e9f20.pdf

- O'Donahoo, J., & Simmonds, J. G. (2016). Forensic patients and forensic mental health in Victoria: Legal context, clinical pathways, and practice challenges. Australian Social Work, 69(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2015.1126750

- Ogloff, J., & Sheehan, R. (2014). Balancing legal, cultural and human rights with the forensic paradigm. In R. Sheehan, & J. Ogloff (Eds.), Working within the forensic paradigm (pp. 272–278). Routledge.

- Payne, J. (2007). Recidivism in Australia: Findings and future research (No. 80). Australian Institute of Criminology. http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/rpp/61-80/rpp80.html

- Ratliff, A., & Beyer, M. (2019). Introduction and overview. In A. Ratliff, & M. Willins (Eds.), Criminal defense-based forensic social work (pp. 1–17). Taylor & Francis.

- Robbins, S. P., Vaughan-Eden, V., & Maschi, T. M. (2014). It's not CSI: The importance of forensics for social work education. Journal of Forensic Social Work, 4(3), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/1936928X.2014.1056061

- Schaffer, K. (2021). Protecting and promoting client rights. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824426-5.00002-7

- Sheehan, R. (2012). Forensic social work: A distinctive framework for intervention. Social Work in Mental Health, 10(5), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2012.678571

- Sheehan, R. (2014). Practising in the forensic context: A cross-disciplinary perspective through the social work lens. In R. Sheehan, & J. Ogloff (Eds.), Working within the forensic paradigm (pp. 9–24). Routledge.

- Sheehan, R. (2016). Forensic social work: Implementing specialist social work education. Journal of Social Work, 16(6), 726–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316635491

- Stout, B. (2017). Community justice in Australia. Allen & Unwin.

- Tilbury, C., Osmond, J., & Scott, T. (2010). Teaching critical thinking in social work education: A literature review. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 11(1), 31–50. http://hdl.handle.net/10072/38225

- Turner, S. (2022). Forensicare RMIT social work partnership: Flourishing through the pandemic. In R. Egan, B. Haralambous, & P. O’Keeffe (Eds.), Partnerships with the community: Social work field education during the Covid-19 pandemic (pp. 61–70). RMIT University in partnership with Informit Open.