ABSTRACT

Neo-liberalism has driven a crisis in Social Work Field Education (SWFE) globally, creating competition, funding cuts, increased workload, and limited capacity to support students. This has been exacerbated by widespread disruptions associated with the global pandemic and other disasters. This article outlines how one Australian university SWFE team has enhanced placement opportunities for students and industry during times of crisis, via a partnership approach. Outcomes include multiple student placements, joint initiatives, mutual relationship, and reciprocity, placing all students during a pandemic. The article contributes to addressing global SWFE challenges, provides a framework for consideration, and identifies areas for further investigation.

An innovative SWFE partnership model can assist universities and industry to withstand global crises impacting placements.

Committed partners and placements, collegial relationships, and a reference group that collaboratively sets agendas for agency and university increases placement opportunities for all students.

IMPLICATIONS

Neo-liberalism has driven a crisis in Social Work Field Education (SWFE) in recent decades, creating competition, funding cuts, increased workload and limited capacity to support students (Hardy et al., Citation2021; Zuchowski et al., Citation2019). Associated with this development have been increased student enrolments and decreasing SWFE opportunities. This situation has been exacerbated further since the 2020 global pandemic (O'Keeffe et al., Citation2023). One Australian university has used a variety of strategies to address the challenges. This has included provision of “in-kind” resources in relation to formal and informal partnerships with agencies; placements in education settings (primary, secondary, public, and private schools); or specialist fields of practice forming the major “cluster” model for offsite supervision (provided by the university). Pilot partnerships with numerous agencies and multiple students were undertaken initially in 2011. However, as the crisis continued, creative solutions were required which involved the field in the response.

Decreased SWFE opportunities is not unique to Australia; it has been highlighted that the future of SWFE lies in closer relationships between universities and the field (Bogo, Citation2015). Universities have recognised the need to engage and partner with communities, but the challenge is how to operationalise engagement. To meet these challenges, many Australian FE programs have developed strategies to establish new placement models and to collaborate with various partners in providing FE (Zuchowski et al., Citation2019).

Other literature informing university and community engagement relates predominantly to research partnerships between the community and universities. Drahota et al. (Citation2016) recommended using a single term, Community-Academic-Partnerships (CAPs), and a conceptual definition to unite multiple research disciplines and strengthen the field. There is substantial contribution in the CAP literature from social work because the identified processes creating effective partnerships are foundational to social work values, ethics, and education. This literature informed the practice presented in this article, hereafter described as “the partnership model” of one university.

The university has been working closely with partners to deepen relationships with community organisations in advancing FE, developing partnered project work for student learning and assessment, and leveraging to progress collaborative research. Partnerships between the academy and community organisations are fundamental to the delivery of social work education, providing “the context for FE to take place as part of students learning experiences” while enhancing program delivery (Egan, Citation2018, p. 1).

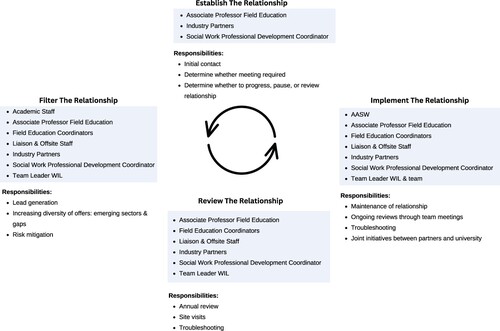

This article conceptualises a model developed to address the global challenges in FE and provides a framework for consideration and investigation. It sets the scene for a PhD study aimed at investigating the collaborative practices developed by SWFE practitioners to address the global challenges of placement opportunities. In this article the authors reflect on this model and recognise areas that need further enhancement. The model relies on all internal and external stakeholders working collaboratively (refer ). The model has not been formally evaluated. Understanding the model in the context of other FE programs is a next step, which is the focus of the PhD study being undertaken by author one.

The Partnership Project

In 2012 the university FE team consulted agencies, peak bodies, and recruitment organisations to explore potential changes in the structure of social work programs to accommodate FE strategies and models appropriate to the major stakeholders over the next 3–5 years (Hawkins, Citation2012). This social work program sits within a School of Social Sciences, where there is less reliance on paid clinical placements and greater commitment to not-for-profit community agencies. Some local schools of social work sit within health faculties, which coincide with payments by the school of social work on a per placement basis. As this is not the case in this school, creativity is paramount in growing placement capacity.

The 2012 consultation produced important insights regarding workforce development with most organisations seeking work-ready qualified experienced staff. Recruitment in the sector was being taken more seriously, with high-demand areas for positions in aged care, child and family services, refugee services, mental health, disability, and homelessness. These insights are supported by research identifying FE as a vehicle for employability in social work (Bloomfield et al., Citation2013). Participants’ suggestions included university-led external (offsite) supervision models when onsite social work supervisors were not available, internships, payment for placement, and partnerships for multiple students. Consultation recommendations included the provision of offsite supervision, financial contribution for provision of onsite supervision, better access to university resources, training and/or professional development, building research capacity, and accessing resources for research, evaluation, and social-action projects.

From this 2012 consultation, a partnership strategy was developed. It began with approaches to existing long-term community partners, who were providing placements for many years. Through these negotiations, different organisations agreed and different reciprocal arrangements were developed, depending on organisation needs. For some, where there were limited qualified social work staff, they required the university to provide offsite supervision in line with ASWEAS requirements (Australian Association of Social Workers, Citation2020). Others had qualified social workers and required some contribution to the provision of onsite supervision, or wanted more in-kind contributions: e.g., training, accessing university resources, or building research capacity. As the number of partners grew so did the commitment to the model and interest from other organisations. Many agreed to take on a minimum of ten students annually, as their commitment to the model.

In 2015, at the instigation of the group of partners, the University and Industry Partnership Reference Group (PRG) was convened (Egan, Citation2018). This group set the annual agenda about different activities they were interested in pursuing over a 12-month period. The relationship became reciprocal whereby the industry agency and university brought complementary roles to the partnership. Whilst this concept may not be unique, the collaborative partnership with this specific model has worked beyond the provision of placements and achieved a series of key outcomes outlined below. It is based on the Community-Academic-Partnerships (CAPs) literature, drawing on values aligned with social work. Although the notion of university–industry partnerships in field education is not new, what is noteworthy here is the prolonged engagement of the university with its industry partners in ways that have resulted in mutually beneficial work and outcomes beyond the provision of placements. The unique contribution of this model is that it has created the conditions to build a strategic alliance across a range of education, practice, and research activities, and to maintain and grow this alliance despite widespread disruptions.

The group remains keen to monitor and input into university processes to improve placement provision, grow their organisation’s involvement with the university and improve reciprocity between the partners and the university. Joint funding applications between the partners and the university social work team were successfully developed for events and projects through internal university funding aimed at promoting industry-engaged networks. These grants allowed for the development of training and/or professional development opportunities, assistance with research, capacity building, and access to university resources to create a sustainable community of practice, and to demonstrate commitment to partnerships ensuring the longevity of a model for placement provision. The first of these events resulted from the Partnership Reference Group’s interest in building organisational research capacity.

How the Partnership Model Works

outlines the model with stakeholder roles and different stages. There are four stages to the ongoing management of the model with each stakeholder having specific roles in partnership relationship. It is a dynamic relationship, evolving over time, depending on partner needs. Partner/university placement requirements are regularly reviewed. The model is based on a developmental learning approach where the team has been open to listening and integrating feedback to continually improve the model and is very much a work in progress.

In the first stage, a new partnership begins with either potential interest from industry or an approach from the university and often starts as a pilot and with phased implementation. After the initial pilot phase, industry may agree to partner and take up the full 10 students, negotiating how the partnership will be approached, and is invited to join the PRG. At this stage, the partner is supported by the Social Work Professional Practice Coordinator and Associate Professor of FE. There is no fixed time to the development of a partnership. It is a flexible approach, based on organisational stability and readiness. Leadership is critical at the early stage of development and throughout the partnership relationship.

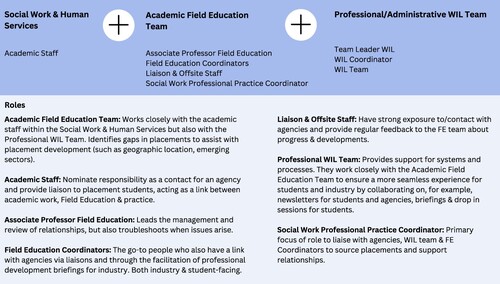

The position of Associate Professor of FE was fundamental to the development of the model. A senior figure in the role to establish and maintain industry collaborations was highly valued in the academic setting. The position brought a range of attributes: e.g., legitimacy in the academy and field, high-order skills in networking and collective action, and a longstanding commitment to collaborative work practices. outlines the roles of internal university team members and depicts integrative approaches between academic and administrative processes that lead to a smooth transition of tasks internally.

Once the partnership is established, the FE Coordinators and Global Urban and Social Studies Work Integrated Learning (GUSSWIL) team assume responsibility, reflecting strong internal collaboration between the FE administrative team and academic team, which is clearly articulated to industry partners. Negotiation occurs with the AASW if any issues arise regarding ASWEAS requirements. A collegial internal approach has contributed to the success of the model, leading to a smooth transition of tasks between staff. This process also requires role clarity and regular communication via team meetings and daily communications. This, in turn, means students and industry are experiencing a more coordinated and seamless service. Examples include communication with students and industry via regular newsletters, drop-in student sessions, and professional development briefings for industry. Partner relationships enable the administrative team to provide better support to industry and develop more responsive systems, placing less demand on industry. Permanent academic staff nominate responsibility as a contact for an agency and provide liaison. The benefit to the academic staff is exposure to practice, retention of practice currency, and the development of contacts for research opportunities. Casually employed liaison and supervision staff have strong exposure to agencies and provide regular feedback to the FE team about progress.

There have been many benefits to students and agencies. Students have been placed in groups, rather than individually, enhancing peer support. The FE experience is such a critical element in student learning, from the preparation stage (Catherine et al., Citation2011) to the actual experience. For industry, there is the provision of participating in regular partnership meetings where they can collaborate to discuss emerging needs and opportunity to be involved in customised professional development. Knowing they have regular groups of students allows industry partners to plan projects and practices as a continuum of ongoing activity.

Outcomes

Since its inception, the partnership model has seen a variety of outcomes which have occurred in concert with industry. At the 2015 reaccreditation of the social work program, the PRG made it clear to accreditors that they wanted students across the academic year, not just in one semester and as a result the curriculum was restructured to enable this to occur. This outcome is significant as it positions the PRG as a site for change. Students now go on placement across the academic year. The following provide a summary of additional model outcomes.

Events

The 2016 Social Justice Research Forum was a day event to build collaborative research capacity for partners using the expertise of university academics (Egan, Citation2018, p. 8). There was diverse research capacity across partners; therefore, a consultation process was designed to respond to this difference in planning and facilitating the day. Outcomes included access to knowledge about building research capacity in community organisations, planning joint research grant applications with the university, work on a collaborative project, steps to develop adjunct academic positions, and future training plans. In 2017, a Co-design Masterclass was facilitated for partners with the purpose of demonstrating the use of co-design strategies through using an organisational challenge faced by one organisation partner (Egan, Citation2018, p. 8). It was through this real-life application that the partner’s Board of Management was able to progress a problem faced by them.

Publications

A series of publications have been produced to support the partnership work between industry and academia (Egan, Citation2018; Egan et al., Citation2020; Johnson et al., Citation2018). In 2018, the PRG book project was developed where twelve partners worked together on producing a book, which documents the history of FE, gathers stories of partners and the types of placements they have provided (Egan, Citation2018).

Grants, Projects, and Positions

A series of projects with partner agencies have been undertaken that involved addressing knowledge gaps in a collaborative manner. The focus has included violence and mental health (Watson et al., Citation2020), Tangentyere Council Alice Springs Women’s Safety Committee Two Way Learning Project, and a Forensicare Industry Fellow academic position, which has been a joint industry and university fellow.

Research

Industry Consortia Scholarships have been developed in partnership with industry to enhance the relationship and build capacity between industry and academia.

The FE Hub and Access to Professional Development and/or Training

In 2018, the University built an external-facing online university social work portal, the Hub, a central point of entry and communication. This occurred in response to a partner’s request for greater access to university resources. This combines with regular professional development and/or training.

The Global Pandemic (2020–2021)

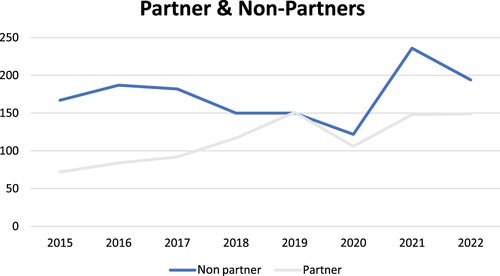

Events were paused during the global pandemic (2020–2021), during which time the focus for agencies and the university was managing services and students’ placements. The challenges of these circumstances were captured in research with agencies and recently published in a second edition of the Partnership Book (Egan et al., Citation2022). Data indicated the strength of the relationships helped foster ongoing placements for students regardless of challenges agencies were facing (refer ). outlines the “Number of field placements in Partners and Non-Partners organisations” pre- and during the pandemic and consistent growth in placements. All students were placed during the two years of the global pandemic. The requirement to continue to service clients in challenging times meant partners knew they could draw on their relationship with the university FE team. Partners committed to students and seized the opportunity to develop new approaches to social work, such as making wellness calls to seniors who were isolated during lockdowns (O'Keeffe et al., Citation2023).

Discussion

The partnership model has resulted in positive relationships with industry, including a range of opportunities for partners to contribute to FE. It has resulted in increased and guaranteed placement opportunities for students, which has created supportive, positive, predictable, varied, and consistent learning opportunities in line with ASWEAS requirements, where students are often placed in groups of fellow students. provides an overview of partner placement growth. The number of partnerships has consistently been about 20 agencies over the years.

The flexibility of the model and the focus on capacity building have been key enablers. The model has been flexible in that the FE team has tailored their response to industry partners in recognition of their capacity at the time. For example, for a small ethnic organisation, the approach might be more staged. With a much larger, national not-for-profit, they may commence with ten students at the outset. Professional development for industry partners is responsive and flexible, offered frequently, and delivered on- or offsite. To date, the model has been self-sustainable as the partnerships have provided guaranteed annual placements and agencies have had guaranteed student numbers via their commitment. Most partner placements are rolled over annually. Students are a key stakeholder but at this stage are not represented in the model: an area for further development. Data on student experiences indicate the benefits and learnings in a group supervision setting when undertaking placements with partner agencies (Egan et al., Citation2021; RMIT Social Work, Citation2018).

The Associate Professor FE (see ) leads the management and review of relationships, but also troubleshoots when issues arise. As mentioned, having this senior role focused on providing strategic leadership and managing relationships indicates to partners the importance of collaboration. The GUSSWIL team provide administrative support to partner agencies once a placement is secured. Most partner agencies have a nominated contact person, who coordinates placement activities at the agency, and liaises with the FE and GUSSWIL teams. Having key contacts on both sides of the relationship and partner agencies involved in the placement allocation process is essential for the work of GUSSWIL teams.

While flexibility is an enabler, it is also a challenge. Each relationship is customised, leading to variability in processes and practices. The development of a more consistent relationship approach has been considered and needs further investigation. Using a staged partnership model means more resources are devoted to the earlier stages, which can vary, depending on agency capacity. While mapping the partnership model () has assisted in articulating the staged approach, further work is required to manage resources, determine the value of the process, and evaluate its worth from all stakeholder perspectives.

In addition to the agency’s capacity, other organisational factors can hinder the relationship. These factors include poor communication about roles and expectations, the time commitment required to manage student placements but also to supervise, and organisational change (Drahota et al., Citation2016). Similarly, interpersonal factors play a role, where trust is built over time. There may also be occasions where personnel change and partnerships fail.

Experiences indicate that regardless of the nature of the organisational settings, all parties acknowledge shared values and that is where the success of the model lies (Meares, Citation2008; Ostrander & Chapin-Hague, Citation2011). These common values enhance student experience to make a difference to the agency, ensure that they get the best possible learning outcome and support social-justice outcomes for service users.

While the accreditation requirements provide a structure and framework, they are not easily adaptable to the speed of change in the sector. This can unfortunately inhibit innovation. For example, virtual or online placements and recent e-health initiatives have not been commonly practised but have become more prominent during the COVID pandemic (2020–2021). The impact of the pandemic on the sector has begun to be documented (Banks et al., Citation2020) and this university is exploring the impact on partners.

This article has presented and analysed a practice by one Australian university SWFE team to facilitate conversations around partnership models within the tertiary environment. It is recognised that most of the evidence is anecdotal and the next steps are to formally evaluate outcomes with partners and students and in light of the current crisis of the pandemic. Evaluating the model will focus on benefits and challenges. It will include an analysis of various approaches and elements such as research, direct practice, policy placements, and examining the impacts of external factors (e.g., COVID-19). Student roles in the model need further consideration. A formal evaluation will cement the learnings and help refine the model.

Conclusion

The model developed and implemented by this University FE team in response to the contextual crisis in FE, continues to evolve and adapt to the changing needs of placement provision. The strategy has increased the provision of local placements, represented a range of sectors, and has grown placement numbers in sectors traditionally not taking many social work students (Egan, Citation2018). While the model started as a way of enhancing placement opportunities for students, it has evolved to address knowledge gaps, translating current concerns in the sector into issues that gain academic attention and learning opportunities for students, FE programs, and industry partners in the field. Knowledge to date indicates that this model is unique, but further scoping is required to explore other approaches to FE with industry and in-house WIL teams as well as the impacts of this approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Patrick O’Keeffe and Dr Christina David (School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT) for providing valuable advice and guidance.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2020). Australian social work education and accreditation standards. https://www.aasw.asn.au/careers-study/education-standards-accreditation.

- Banks, S., Cai, T., DE Jonge, E., Shears, J., Shum, M., Sobočan, A., Strom, K., Truell, R., Uriz, M., & Weinberg, M. (2020). Practising ethically during COVID-19: Social work challenges and responses. International Social Work, 63(5), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820949614

- Bloomfield, D., Chambers, B., Egan, S., Goulding, J., Reimann, P., Waugh, F., & White, S. (2013). Authentic assessment in practice settings: A participatory design approach. Office of Learning and Teaching, Australian Government.

- Bogo, M. (2015). Field education for clinical social work practice: Best practices and contemporary challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(3), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5

- Catherine, M., Craik, C., Hawkins, L., & Williams, J. (2011). Professional practice in human service organizations. Allen & Unwin.

- Drahota, A., Meza, R., Brikho, B., Naaf, M., Estabillo, E., Gomez, E., Vejnoska, S. F., Dufek, S., Stahmer, A. C., & Aarons, G. (2016). Community–academic partnerships: A systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. Millbank Quarterly: A Multidisciplinary Journal of Population Health and Health Policy, 94(1), 163–214.

- Egan, R. (2018). Partnerships with the community: Forty-five years of social work field education at RMIT. RMIT University.

- Egan, R., David, C., & Williams, J. (2021). An off-site supervision model of field education practice: Innovating while remaining rigorous in a shifting field education context. Australian Social Work. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1898004

- Egan, R., Haralambous, B., & O’Keeffe, P. (2022). Partnerships with the community: Social work field education during the COVID-19 pandemic. RMIT University.

- Egan, R., Lambert, C., & Ogilvie, K. (2020). The value of community-academic partnerships in field education. Challenges, opportunities and innovations in social work field education. Routledge.

- Hardy, F., Chee, P., Watkins, V., & Bidgood, J. (2021). Collaboration in social work field education: A reflective discussion on a multiuniversity and industry collaboration. Australian Social Work. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1924811

- Hawkins, L. (2012). Alternate social work and field education options. Exploratory project report. Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.

- Johnson, B., Laing, M., & Williams, C. (2018). The possibilities for studio pedagogy in social work field education: Reflections on a pilot case study. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 20(2), 90–100.

- Meares, P. A. (2008). Schools of social work contribution to community partnerships: The renewal of the social compact in higher education. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 18(2), 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911350802317194

- O’Keeffe, P., Haralambous, B., Egan, R., Heales, E., Baskarathas, S., Thompson, S., & Jerono, C. (2023). Reimagining social work placements in the Covid-19 pandemic. The British Journal of Social Work, 53(1), 448–470. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcac124

- Ostrander, N., & Chapin-Hague, S. (2011). Learning from our mistakes: An autopsy of an unsuccessful university-community collaboration. Social Work Education, 30(4), 454–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2010.504768

- RMIT Social Work. (2018). Partnership with the community: Forty–five years of social work field education at RMIT.

- Watson, J., Maylea, C., Roberts, R., Hill, N., & McCallum, S. (2020). Preventing gender-based violence in mental health inpatient units. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety Limited (ANROWS).

- Zuchowski, I., Cleak, H., Nickson, A., & Spencer, A. (2019). A national survey of Australian social work field education programs: Innovation with limited capacity. Australian Social Work, 72(1), 75–90. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2018.1511740