ABSTRACT

Social work external accrediting bodies are moving towards competency-based models that require educational providers to demonstrate that students meet specific competencies at graduation. It is expected that all social work students at accredited social work programs in Australia will have acquired specific graduate attributes and demonstrated the associated learning outcomes by the completion of their degree. The purpose of this study was to investigate the experiences and benefits of using an ePortfolio with Master of Social Work students (n = 43) to critically reflect on their own learning and demonstrate how they met the Australian Association of Social Work graduate attributes necessary for accreditation. The findings revealed that students’ perceived level of readiness for practice and identity as a professional social worker increased with the successful completion of the ePortfolio. The study also identified barriers and enablers in implementing the ePortfolio as an assessment piece to document overall program learning outcomes. The conclusion discusses how ePortfolios are a viable assessment tool in the online and blended learning space that has benefit for both the student and the program in demonstrating learning outcomes and compliance with accreditation graduate standards.

Academic ePortfolios are an effective tool for student reflection and communication of competence of required graduate outcomes.

Student self-assessment of graduate attributes can strengthen professional identity and preparedness for professional practice.

The ePortfolios benefit students and social work educators by sharing the accreditation-obligated responsibility of ensuring that AASW graduate competencies are met.

IMPLICATIONS

KEYWORDS:

- Social Work

- Education

- Social Work Educators

- Social Work Students

- Master of Social Work Students

- Social Work Graduates

- Technology

- Computers

- Eportfolio

- Graduate Attributes

- Pebblepad

- Accreditation

- Assessment Aids

- Self-Assessment

- Technology Assisted Assessment

- Technology Assisted Learning

- Professional Identity

- Self-Efficacy

- Critical Thinking

- Self-Reflection

- Australia

The current challenge facing Australian social work educational institutions is proving that students are meeting graduate attributes in line with the eight domains listed in the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) Education and Accreditation Standards (AASW, Citation2021; Australian Council of Heads of Social Work Education, Citation2023). The authors contend that ePortfolios offer a workable evaluation method that can encourage student ownership in showcasing graduation competencies and can empower both educators and students. The AASW Practice Standards establish the attributes of Australian social work graduates (AASW, Citation2021). These standards serve as indicators of the expected outcomes of graduates from social work programs accredited by the AASW. The Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS) identify eight essential practice standards that significantly influence the outcomes of these graduates (AASW, Citation2021):

values and ethics

professionalism

culturally responsive and inclusive practice

knowledge for practice

applying knowledge to practice

communication and interpersonal skills

information recording and sharing

professional development and supervision

Throughout the duration of their degree, it is expected that all Australian social work students enrolled in accredited programs will have acquired these attributes and evidenced the corresponding learning outcomes (AASW, Citation2021).

Currently, the onus is on educational providers to develop and deliver learning outcomes consistent with graduate outcomes to strengthen the profession itself. This presents a challenge for social work educators, who must ensure that students meet graduate attributes as a means of encouraging long-lasting professional identity. Despite most English-speaking countries recognising social work as a registered profession, Australia remains unsuccessful in its efforts to bring social work into the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) (Hallahan & Wendt, Citation2020; McCurdy et al., Citation2018). AHPRA currently oversees most other allied health professions including nursing, occupational therapy, and psychology (AHPRA, Citationn.d.). Australian social work registration occurs through the AASW; this is predominantly an opt-in process, except for South Australia, where membership is mandated by the Social Workers Registration Act 2021 (Tangney & Mendes, Citation2022). Several studies have queried the practicalities and safeguarding measures of a national Australian social work registry (Hallahan & Wendt, Citation2020; Tangney & Mendes, Citation2022). However, it is generally regarded as important to professionalisation, especially for social work graduates, who are navigating and developing their professional identity, and have increased vulnerability in legal, social, and personal spheres (Long et al., Citation2023).

Recent research has examined the extent to which social work education prepares students for practice (Jefferies et al., Citation2022; Moorehead et al., Citation2016; Nuttman-Shwartz, Citation2017). Reflective abilities are essential for preparing students for social work practice. Reflective practice, critical reflection, and reflexivity support students’ preparation for practice by encouraging “problem-solving, building understanding from, and about, practice situations, the use of self, and … improving and learning from practice” (Watts, Citation2019, p. 17). In addition to critical reflection skills, there is a need for a “visible conceptualisation of professional identity in social work education” (Moorhead, Citation2019, p. 984). The development of a strong professional identity is regarded as one of the most influential factors in a social worker's sense of purpose, motivation to engage in ethical practice, and self-assurance to enter the workforce after graduation (Webb, Citation2017). Due to challenging availability of traditional field placements, expecting students to develop professional identity from placement supervision alone is unrealistic (Cleak & Zuchowski, Citation2019; Jefferies et al., Citation2023). This is concerning, as exploring and distinguishing social work identity is crucial for new graduates (Wiles, Citation2013), who have been found to struggle with forming, identifying, and articulating social work identity (Smith et al., Citation2022). According to Nuttman-Shwartz (Citation2017), “students must cultivate a personal sense of being a social worker. This is only possible through opportunities to articulate one's professional identity in the field and in the classroom” (p. 2).

Defining capabilities can assist students in acquiring work-readiness characteristics upon graduation (Howard et al., Citation2015) and strengthen their professional identity. Educators must continue adapting to emergent technologies and innovative approaches to instruction that align with the student graduate attributes. Apgar (Citation2019) stated that capstone projects are an effective method for students to demonstrate and implement knowledge acquired throughout their course and field work. Completing a capstone project in the final year enables students to consolidate their knowledge, skills, and learning competencies to enhance their practice readiness and skill transferability (McNeill, Citation2011). The ePortfolio aids are a contemporary, technologically sound platform for scaffolding these learning assets with evidentiary capabilities (Faulkner et al., Citation2013; Hamilton et al., Citation2023). The capacity to demonstrate graduate attribute attainment is associated with higher outcomes of perceived and actualised readiness for practice, as well as a stronger sense of professional identity. The aggregation made possible by capstone portfolios also is linked to the concept of “assessment as learning”, wherein the process of compiling evidence of demonstrated knowledge and integration of practice skills improves practice readiness (Allen & Coleman, Citation2011).

Australian higher education is regulated through the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) and the Australian Qualification Framework (AQF); these policies set national standards and learning outcomes. Their current “job-ready” focus is a performance-based funding model that stresses student enrolment, participation, and retention (Cox et al., Citation2021; Long et al., Citation2023). In addition to TEQSA, social work degrees are accredited by the AASW’s Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS) (AASW, Citation2021). Accrediting bodies of social work education have shifted the emphasis from directly measuring learning outcomes and program objectives to determining program outcomes through the evaluation of social work students’ mastery of core competencies or graduate attributes (Australian Council of Heads of Social Work Education, Citation2023). This shift challenges social work educational institutions to develop ways to ensure that individual students meet the graduate attributes set out by their professional accrediting bodies (Meyer-Adams et al., Citation2011). According to Salm et al. (Citation2016), measuring competencies against specific standards aids in determining whether students possess the technical and professional skills required for their career path. Internationally, the United States Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards recognise a “holistic view of competence; that is, the demonstration of competence is informed by knowledge, values, skills, and cognitive and affective processes that include the social worker’s critical thinking, affective reactions, and exercise of judgment in regard to unique practice situations” (Council on Social Work Education, Citation2022, p. 7). Critiques of competency-based education highlight the emphasis on technicist skills and managerial processes over a student's ability to “think” (Larrison & Korr, Citation2013). The use of an ePortfolio promotes a student-centered approach to competency through “deep learning” (Baeten et al., Citation2010) and critical reflection. These ePortfolios encourage students to take ownership of their learning by recording evidence of learning as self-reflection, artefacts, and other records that demonstrate the development of social work practice skills and reflect graduate characteristics (Venville et al., Citation2017). In higher education, the use of online and hybrid learning approaches is expanding. When assessing learning outcomes in both online and blended learning environments, social work educators are increasingly embracing novel technology (Davis et al., Citation2019). Traditional didactic teaching is gradually being replaced by more learner-centered, interactive, and active methods that encourage students to take ownership of their own education (Mostrom & Blumberg, Citation2012).

With the evolution of educational technology spurred on by the need to adapt pedagogy during the COVID19 pandemic (Jefferies et al., Citation2022), education programs are struggling to develop measures that captivate student attention and satisfy assessment requirements (Parker, Citation2007). The use of ePortfolios in education is not new to social work (Venville et al., Citation2017), but most research has focused on the use of ePortfolios in single courses (Ajandi et al., Citation2013; Atkins & Sykes, Citation2021; Sidell, Citation2003), rather than as a means of assessing end-of-program graduate attributes and competencies. A few studies (Hanbridge et al., Citation2018; Housego & Parker, Citation2009; Posey et al., Citation2015) have demonstrated the program-wide benefits of ePortfolio use. In the Australian context, there is a gap in the literature regarding the use of ePortfolios to support the assessment of social work students’ graduate attribute competency as required for external social work accreditation. Venville et al. (Citation2017) investigated the use of ePortfolios in social work field education and found them useful for documenting evidence and facilitating communication between students and instructors. It also has been determined that ePortfolios effectively capture evidence of learning in various forms of assessment (Hanbridge et al., Citation2018; Reece & Levy, Citation2009). Presented in electronic form, they provide flexibility for engagement and access, which is particularly pertinent to the needs of modern learners (Campbell & Tran, Citation2021). However, Faulkner et al. (Citation2013) argued that these benefits are restricted to students who recognise the importance of personal and professional development.

Considering the challenges that social work education faces when preparing students for practice and ensuring attribute competency, additional research is required to consider effective teaching tools. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of ePortfolios as a teaching and learning instrument from the perspective of Master of Social Work (MSW) students. Specifically, this study aimed to determine the effectiveness of ePortfolios on students’ critical reflections on their own learning and demonstrations of AASW graduate attribute competency.

Methods

Research Design

This research used a mixed methods survey design (Shorten & Smith, Citation2017) to assess student perceptions about the effectiveness of using an ePortfolio (PebblePad) as the capstone project to assist MSW students in meeting the graduate attributes and preparing for professional practice. The authors are social work educators who have experience with using ePortfolios in course work and recognised a gap in knowledge about student perceptions of the effectiveness of ePortfolios for demonstrating graduate attributes.

Participants

Final year MSW students (n = 124) at a regional university in Australia undertaking their professional placement of 500 hours completed an ePortfolio capstone task using PebblePad. Following the completion of the capstone assessment task, students were invited via email to complete an online survey conducted through Survey Monkey about their experience of completing the ePortfolio. The online survey was voluntary, and students were free to stop the survey at any time. Forty-three participants completed the survey. The majority (67%) identified as female, international students (79%), and were studying full-time (91%). Participants ranged in age from 18–55 years, with the majority (88%) being 23–45 years old. The demographic data are reflective of the general cohort of students in this program except for the international ratio, which was slightly higher than expected, given that the program averaged approximately 50% international students.

Procedure

The capstone assessment was undertaken within their placement course and required students to create an artefact that synthesised their learning over the two-year program and evidenced how they met each of the AASW graduate attributes. Students were required to address each attribute and document how they met that attribute through their specific courses, assessment task, and field placement experiences. The ePortfolio was assessed and graded by the Head of Social Work (and author) to ensure that each student met the graduate attributes prior to graduation.

Data Collection

Data was collected from the MSW cohorts over a three-year period from 2019–2021. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. Descriptive data were collected for responses to demographic items and students’ experiences in completing the ePortfolio. In addition, qualitative questions included the following: what did you like best about the PebblePad ePortfolio tool; what did you like least about using PebblePad; what barriers, if any, did you encounter in using PebblePad; and do you have any other comments or feedback? All data were collected anonymously, and implied consent was obtained by clicking on the survey link.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data for the study were analysed in IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26. Descriptive statistics were calculated using univariate analysis (Agresti, Citation2018). Qualitative data were analysed using inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Participants’ qualitative survey responses were manually coded, and themes generated, reviewed, and defined through a heuristic process. To support academic rigour and credibility, themes were reviewed by all authors to reach consensus on the findings. The following steps were undertaken: 1. familiarisation with, and organisation of, transcripts; 2. identification of possible themes; 3. review and analysis of themes to identify structures; and 4. construction of theoretical model, constantly checking against new data (Guest et al., Citation2012). Ethical approval for this research was granted in 2018 by the University of the Sunshine Coast Human Research Ethics Committee (Ethics approval number A17971).

Findings

Findings revealed that the participants’ level of technology literacy varied, with nearly half (n = 21, 49%) reporting advanced skills, just under half (n = 19, 44%) intermediate skills, and only a few (n = 3, 7%) reporting basic skills. As shown in , the ePortfolio was viewed as positive or useful in meeting the mandatory national accreditation graduate attributes, transitioning to professional practice, and preparing for employment opportunities. The majority of participants were confident that they met the AASW graduate attributes (78%) and that the ePortfolio was helpful for demonstrating how they met the graduate attributes (67%). In addition, the majority of participants reported that the ePortfolio helped them to develop a sense of professional identity (68%), prepare them for professional practice (59%), address job selection criteria (62%), and gain employment postgraduation (51%). Furthermore, 66% thought the ePortfolio was a useful tool for entry into social work practice, and 68% viewed the ePortfolio as a useful tool to use after graduation for career progression. Although the majority (67%) would recommend the ePortfolio to other students, most (73%) would have liked it introduced at the beginning of their program as opposed to the final semester.

Table 1 Participants’ Views on the Usefulness of the ePortfolio

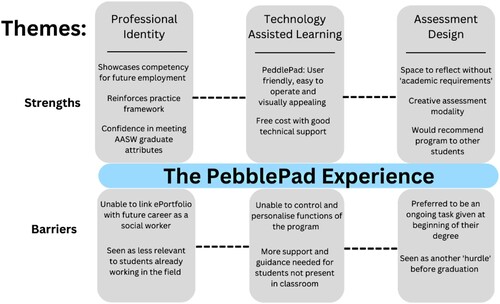

Qualitative thematic analysis revealed three central themes: professional identity, technology-assisted learning, and assessment design (see ).

Theme 1: Professional Identity

The first theme that emerged from the data focused on the development of professional identity for participants. The findings revealed that students’ perceived readiness for practice and sense of professional social work identity increased with the successful completion of the ePortfolio. Consistent with the quantitative data, most participants identified reflection and professional identity as a key strength of their ePortfolio project, as this participant explained, “I was able to reflect on my university and placement experiences and found this useful for expanding my knowledge and practice (P1)”. The experience of completing the ePortfolio encouraged critical reflection on both the student’s field placement and on their social work studies more broadly, “(it) was more of a self-reflection than a task. It reminded me of what I have achieved and learned throughout my journey (P10)”.

For some participants, completing the ePortfolio explicitly reinforced key knowledge connected to graduate attributes. One participant stated, “I remembered AASW Code of Ethics, which are very useful for a social worker (P2)”, with another explaining that the ePortfolio was “clearly divided into eight parts in following AASW requirements (P6)”.

In addition to reflecting on ethics and practice standards, some participants identified that completion of the ePortfolio encouraged them “to articulate and put into words my thoughts (and) encouraged me to think of examples (P3)”, thus reinforcing their developing practice framework:

I liked how it helped me and guided me in my summarising my experience; it helped me reflect on certain examples of the skills I acquired and also how social work studies and placement changed my personal views on the world. (P5)

[ePortfolio] did not help in understanding graduate attributes and was not at all helpful in gaining employment. The amount of information required was quite extensive and I don’t think sharing this with potential employers would be what they are looking for. (P31)

Theme 2: Technology-Assisted Learning

The second theme that emerged from the data focused on the technology of an ePortfolio. The ePortfolio’s unique design and features were noted as a strength by many participants. Participants identified “ease of use (P17)” and accessibility as strengths of the ePortfolio. Many of the participants described the ePortfolio as easy to navigate and described it as “user friendly (P25)”, “easy to use (p24)”, and “easy to operate (P27)”. Accessibility of the PebblePad tool was reported as a key strength by many participants. Participants noted benefits such as “free of charge (P25)”, “flexibility (P39)” of access, and “good technical support (P40)” as central to their satisfaction in using the technology. Participants noted that certain features of the tool such as “easy editing and formatting tools (P13)” assisted them when completing their ePortfolio task.

Several participants noted that the clear and comprehensive presentation of the tool was appealing to them as it used simple terminology and prompts to guide completion. For some participants, a strength of the ePortfolio was its ability to improve their readiness for practice postgraduation due to features such as providing “essential information about how to write resumes (P16)” and that “it can last long even after graduation and displays different sections that can be accessed by potential employers (P14)”.

Several key barriers to ePortfolios were identified from the data including technical difficulties and learning a new system. For a few participants, learning how to navigate PebblePad was confusing, especially at the beginning, and a frustrating experience that was a “steep learning curve (P27)”. Despite these initial challenges, most students developed confidence in use of the tool as this participant noted, “first, I am confused using it. But, after watching (instructional) video, I did everything very well (P2)”.

Some students experienced frustration at the technical problems they encountered when completing their ePortfolio such as “forgetting to save and losing my work (P1)”, “no word count feature (P38)”, and “difficulty changing font size (P22)”. Most students who became frustrated with the features of PebblePad were seeking more control over the creative and personalised functions of the program, such as changing their profile picture, changing the design and colour, and reordering pages. For a few participants, navigation of the tool was “a slow process (P34)” as this participant noted, “I didn't like much the technical side—swapping between Domains was a little uncomfortable (P5)”.

Theme 3: Assessment Design

The final theme that emerged from the data focused on the design of the ePortfolio task. Most participants were positive about this type of assessment and would recommend it to other students. Some participants appreciated the unique features of this type of assessment and noted that the opportunity to engage in purposeful reflection without the constraints of academic requirements provided “a space to reflect on … overall learnings (P2)”, which was free of the usual expectations for student assignments. As this participant explained, “I liked how we didn't have to reference and could just reflect (P35)”. Another participant indicated similar satisfaction with the design of the ePortfolio, stating “it was a fantastic reflection tool to use at the end of the degree as a way of identifying skills and boost[ing] confidence (P15)”. Participants also commented on how the ePortfolio did not have the look and feel of traditional academic work and that it was an “amazing portal (P15)” through which to do their work.

Some participants identified that integrating the ePortfolio earlier in the program of study could be beneficial as it “would have been more useful to have started using this from the beginning of the degree rather than the last semester (P13)”. It was suggested that the ePortfolio could be woven throughout the MSW program in the following way: “It would be good to integrate this within each subject as a reflective journal connecting our learnings into our outside world view. Perhaps this could make up 10–20% of each course and help students refine the self-reflection skillset (P2)”.

For some participants, more guidance and support were needed as they completed their ePortfolio project, with one participant suggesting “some YouTube tutorials on how to use it maybe? I was unable to come to campus so maybe that was covered in workshops. Lots of students do placement away from (campus) though (P37)”.

For a few participants, the ePortfolio presented a barrier to graduation and “another task to do (P3)”, which created more stress: “When you are at the end of the degree, you just want to finish (P29)”. Lack of time to “write during placement (P28)” was seen as a barrier to successfully completing the ePortfolio, with this participant explaining “it took valuable time out of my student placement, which was of actual use in identifying attributes employers and AASW are looking for (P26)”.

Discussion

Social work educators are searching for conceptually and empirically solid strategies to evaluate educational outcomes to foster competency-based educational evaluations. Findings from this mixed methods study highlight the benefits and challenges for students in using an ePortfolio as a tool for assessing and documenting how students meet graduate attributes. It measured the student’s self-assessment of their competence and mastery of the eight ASWEAS graduate attribute domains. Through documenting and recording, social work students needed to critically reflect on their growth and contextualise educational experiences within the graduate competency framework. Although student self-assessment alone has been shown to be limited to student satisfaction rather than learning and effectiveness (Joubert, Citation2021), it is important when paired with educator feedback. In this study, the student self-assessment was reviewed by the educator, who ultimately reviewed, graded, and gave feedback on the ePortfolio. This design gives power to students over their educational experience and shares the responsibility of evidencing individualised outcomes for ASWEAS accreditation guidelines between the student and the educator.

Consistent with existing literature (Apgar, Citation2019; McNeill, Citation2011; Venville et al., Citation2017), the findings established that not only did the ePortfolio promote critical reflection and preparation for practice, but it also provided further insight into ePortfolios as a tool for developing professional identity. Most participants reported having a positive experience completing the ePortfolio, although it is noted that students needed to be equipped with the technological literacy and sufficient assistance to meet the challenge of technology-enhanced pedagogical approaches, as noted in previous research (Davis et al., Citation2019; Harris, Citation2022). The data analysis revealed that participant experiences could be grouped into three themes: professional identity, technology-assisted learning, and assessment design.

Social work professional identity continues to be critically explored and researched throughout Australia (Long et al., Citation2023; Moorehead et al., Citation2016). Professional identity, as a construct, is as diverse as the people, needs, and contexts within which social workers practice. The changing nature of organisational structures, social issues, political landscapes, and world events further add to the evolving role, resources, and barriers that underpin the constant shifts within the social work profession as a practice and identity (Webb, Citation2017). Social work educational institutions in Australia are challenged to demonstrate that individual students are meeting the graduate attributes in accordance with the eight domains of the AASW Practice Standards (Jefferies et al., Citation2023). Defining capabilities and critical thinking can support students to attain graduate attributes for work readiness (Howard et al., Citation2015). As a learning tool, the e-Portfolio provides a format and platform for students to communicate and evidence such competencies to the educator. Education service providers are encouraged to utilise teaching pedagogies that enable students to acquire these capabilities that align with required graduate attributes. Preston-Shoot (Citation2004) argued for differentiation in student competence for practice, during study, and competence in practice, postgraduation. The ePortfolio can assist in such differentiation. This potential has been discussed by Schmidt Hanbidge et al. (Citation2018) who identified that incorporating an ePortfolio into a professional program offers numerous pedagogical advantages, including the synthesising and culminating of the students’ learning experience and professional identity.

The challenge for social work graduates without a strong professional identity is the organisational forces and pressures that may not be congruent with graduate attributes. Long et al. (Citation2023) describe the risks to professional identity for new graduates as working within organisations that do not share social work values, and the absence of a social work network. The fundamental issue for social work educators is meeting the expectations of employers and client needs by addressing concerns about the legitimacy of education and professional identity in preparing students for the professionalisation process (Frost et al., Citation2013). The key findings from this study suggest that ePortfolios are an effective tool for helping students demonstrate graduate outcomes and strengthening professional identity and preparedness for social work practice. It has been recognised that social work education requires accurate and efficient techniques to evaluate student competence. The implementation of an ePortfolio as a capstone project supports students to demonstrate standards and prepare for practice.

Limitations

Further research is required on how to embed the ePortfolio tool within placement assessment and activities to avoid repetition and cognitive overload. Further research is needed to understand if utilising ePortfolios earlier in the degree would further enhance critical reflection and provide a more developmental approach to meeting graduate competencies. It is recommended that the AASW enhance the ASWEAS standards to require social work programs to assess graduate attributes for individual students rather than simply assessing across generic course material.

A limitation of this study was its small sample size, which was recruited from one rural/regional university in Australia; therefore, the results are not generalisable. Further, the survey was online, which required some degree of technical literacy and was based on a self-report of their own learning experiences.

Conclusion

The utilisation of ePortfolios aligns with the current shift towards a student-centered approach, which promotes the cultivation of deep learning. However, it is important to ensure that students have the technology skills and adequate support to adapt to the challenge of technology-enhanced educational strategies. By documenting learning evidence that illustrates social work practice abilities and signifies adherence to graduate competencies in ePortfolios, students can take more control of their education and educational institutions can demonstrate individualised learning outcomes that meet accreditation guidelines.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Agresti, A. (2018). Statistical methods for the social sciences. Pearson.

- Ajandi, J., Preston, S., & Clarke, J. (2013). Portfolio-based teaching and learning: The portfolio as critical praxis with social work students. Critical Social Work, 14(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.22329/csw.v14i1.5869

- Allen, B., & Coleman, K. (2011). The creative graduate: Cultivating and assessing creativity with ePortfolios. In G. Williams, P. Statham, N. Brown, & B. Cleland (Eds.), Changing demands, changing directions (pp. 59–69). Proceedings Ascilite Hobart.

- Apgar, D. (2019). Conceptualization of capstone experiences: Examining their role in social work education. Social Work Education, 38(2), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1512963

- Atkins, P., & Sykes, K. (2021). Embedding holistic learning: Designing curated eLearning processes for social work students. Ascilite 2021 Back to the Future.

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2021). Australian social work education accreditation standards. AASW. https://aasw-prod.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ASWEAS-March-2020-V2.1-updated-November-2021.pdf

- Australian Council of Heads of Social Work Education. (2023). Reimagining field education: Report from the summit 2023. ACHSWE.

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). (n.d.). The national registration and accreditation scheme. Retrieved June 7, 2023 from http://www.ahpra.gov.au/

- Baeten, M., Kyndt, E., Struyven, K., & Dochy, F. (2010). Using student-centred learning environments to stimulate deep approaches to learning: Factors encouraging or discouraging their effectiveness. Educational Research Review, 5(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.06.001

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Campbell, C., & Tran, T. L. N. (2021). Using an implementation trial of an ePortfolio system to promote student learning through self-reflection: Leveraging the success. Education Sciences, 11(6), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060263

- Cleak, H., & Zuchowski, I. (2019). Empirical support and considerations for social work supervision of students in alternative placement models. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0692-3

- Council on Social Work Education. (2022). Educational policy and accreditation standards (EPAS). CSWE. https://www.cswe.org/getmedia/94471c42-13b8-493b-9041-b30f48533d64/2022-EPAS.pdf

- Cox, D., Cleak, H., Bhathal, A., & Brophy, L. (2021). Theoretical frameworks in social work education: A scoping review. Social Work Education, 40(1), 18–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1745172

- Davis, C., Greenaway, R., Moore, M., & Cooper, L. (2019). Online teaching in social work education: Understanding the challenges. Australian Social Work, 72(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1524918

- Faulkner, M., Mahfuzul Aziz, S., Waye, V., & Smith, E. (2013). Exploring ways that ePortfolios can support the progressive development of graduate qualities and professional competencies. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(6), 871–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.806437

- Frost, E., Höjer, S., & Campanini, A. (2013). Readiness for practice: Social work students’ perspectives in England, Italy, and Sweden. European Journal of Social Work, 16(3), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2012.716397

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Hallahan, L., & Wendt, S. (2020). Social work registration: Another opportunity for discussion. Australian Social Work, 73(2), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1666891

- Hamilton, A., Downer, T., Flanagan, B., & Chilman, L. (2023). The use of ePortfolio in health profession education to demonstrate competency and enhance employability: A scoping review. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 14(1), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2023vol14no1art1704

- Hanbridge, A. S., McMillan, C., & Scholz, K. W. (2018). Engaging with ePortfolios: Teaching social work competencies through a program-wide curriculum. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(3), https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2018.3.3

- Harris, S. (2022). Australian social workers’ understandings of technology in practice. Australian Social Work, 75(4), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1949025

- Housego, S., & Parker, N. (2009). Positioning ePortfolios in an integrated curriculum. Education + Training, 51(5), 408–421. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910910987219

- Howard, A., Johnston, L., & Agllias, K. (2015). Ready or not: Workplace perspectives on work-readiness indicators in social work graduates. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 17(2), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.3316/aeipt.212505

- Jefferies, G., Davis, C., & Mason, J. (2022). Simulation and skills development: Preparing Australian social work education for a post-COVID reality. Australian Social Work, 75(4), 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1951312

- Jefferies, G., Davis, C., Mason, J., & Yadav, R. (2023). Using simulation to prepare social work students for field education. Social Work Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2023.2185219

- Joubert, M. (2021). Social work students’ perceptions of their readiness for practice and to practise. Social Work Education, 40(6), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1749587

- Larrison, T. E., & Korr, W. S. (2013). Does social work have a signature pedagogy? Journal of Social Work Education, 49(2), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2013.768102

- Long, N., Gardner, F., Hodgkin, S., & Lehmann, J. (2023). Developing social work professional identity resilience: Seven protective factors. Australian Social Work, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2022.2160265

- McCurdy, S., Sreekumar, S., & Mendes, P. (2018). Is there a case for the registration of social workers in Australia? International Social Work, 63(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872818767496

- McNeill, M. (2011). Technologies to support the assessment of complex learning in capstone units: Two case studies. In D. Ifenthaler, J. Spector, P. Isaias, & D. Sampson (Eds.), Multiple perspectives on problem solving and learning in the digital age (pp. 199–216). Springer.

- Meyer-Adams, N., Potts, M. K., Koob, J. J., Dorsey, C. J., & Rosales, A. M. (2011). How to tackle the shift of educational assessment from learning outcomes to competencies: One program’s transition. Journal of Social Work Education, 47(3), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2011.201000017

- Moorehead, B., Bell, K., & Bowles, W. (2016). Exploring the development of professional identity with newly qualified social workers. Australian Social Work, 69(4), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1152588

- Moorhead, B. (2019). Transition and adjustment to professional identity as a newly qualified social worker. Australian Social Work, 72(2), 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1558271

- Mostrom, A., & Blumberg, P. (2012). Does learning-centered teaching promote grade improvement? Innovative Higher Education, 37(5), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-012-9216-1

- Nuttman-Shwartz, O. (2017). Rethinking professional identity in a globalized world. Clinical Social Work Journal, 45(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-016-0588-z

- Parker, J. (2007). Developing effective practice learning for tomorrow’s social workers. Social Work Education, 26(8), 763–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470601140476

- Posey, L., Plack, M. M., Snyder, R., Dinneen, P. L., Feuer, M., & Wiss, A. (2015). Developing a pathway for an institution wide ePortfolio program. International Journal of ePortfolio, 5(1), 75–92.

- Preston-Shoot, M. (2004). Responding by degrees: Surveying the education and practice landscape. Social Work Education, 23(6), 667–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261547042000294473

- Reece, M., & Levy, R. (2009). Assessing the future: E-portfolio trends, uses, and options in higher education. EDUCAUSE Centre for Applied Research.

- Salm, T. L., Johner, R., & Luhanga, F. (2016). Determining student competency in field placements: An emerging theoretical model. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2016.1.5

- Schmidt Hanbidge, A., Mcmillan, C., & Scholz, K. (2018). Engaging with ePortfolios: Teaching social work competencies through a program-wide curriculum. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2018.3.3

- Shorten, A., & Smith, J. (2017). Mixed methods research: Expanding the evidence base. Evidence Based Nursing, 20(3), 74–75. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102699

- Sidell, N. (2003). The course portfolio: A valuable teaching tool. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 23(3), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v23n03_08

- Smith, F. L., Harms, L., & Brophy, L. (2022). Factors influencing social work identity in mental health placements. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(4), 2198–2216. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab181

- Tangney, M., & Mendes, P. (2022). Should social work become a registered profession? An examination of the views of 15 Australian social workers. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 58, 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.222

- Venville, A., Cleak, H., & Bould, E. (2017). Exploring the potential of a collaborative web-based ePortfolio in social work field education. Australian Social Work, 70(2), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2017.1278735

- Watts, L. (2019). Reflective practice, reflexivity and critical reflection in social work education in Australia. Australian Social Work, 72(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1521856

- Webb, S. A. (2017). Professional identity as a matter of concern. In S. Webb (Ed.), Professional identity and social work (pp. 431–454). Routledge.

- Wiles, F. (2013). ‘Not easily put into a box’: Constructing professional identity. Social Work Education, 32(7), 854–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.705273