Abstract

Scientists are ideally placed to inform, inspire and empower others in science, and thus contribute towards the formation of a scientifically informed society. Despite the increasing emphasis on scientists engaging in Public Engagement in Science, there is not enough structured spaces for scientists to practice. Social-distancing policies incurred by the COVID-19 crisis have forced many PES programmes to move online, incurring further limitations on both training and structured spaces to practice. This pilot study aimed to investigate the impact of participation in four short online training modules and online PES activity on scientists’ perceived science communication skills. I’m a Cell EXPLORERS Scientist Online Chat, is a 35-minute text-based chat where young people (aged 11–15 years old) ask questions about science and being a scientist. Both the training and activity were informed by the ‘Science Capital Teaching Approach’. The participating scientists (N = 11, 8 female and 3 male scientists) comprised a mix of staff and students from four Higher Education Institutions in Ireland. Data were collected via surveys completed after the initial training, directly after each chat, and at the end of the project. Findings indicated that participating in the PES activity increased scientists’ perceived proficiency in various science communication skills.

1. Research background and rationale

Scientists participating in Public Engagement in Science (PES) play an important role in contributing towards the formation of a scientifically literate society (Concannon and Grenon Citation2016; European Commission Citation2002; Thomas and Durant Citation1987). Scientists interacting with non-expert members of the public can have dual benefits: it can combat public distrust and address certain misconceptions associated with science and scientists (Brownell, Price, and Steinman Citation2013; Concannon and Grenon Citation2016; Thomas and Durant Citation1987); and scientists can gain increased confidence and science communication skills (Clark et al. Citation2016; Concannon and Grenon Citation2016; Laursen et al. Citation2007).

Although many Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) include civic and community engagement activities in their mandates (Campus Engage Charter Citation2014; Hunt Citation2011), this often does not translate into practical supports embedded in institutions (Seakins and Fitzsimmons Citation2020). Despite an increasing push for scientists to participate in PES, there is a scarcity of training available for scientists in HEI spaces (Besley et al. Citation2018; Burchell Citation2015), which is one of the key barriers for participation cited by scientists (BBSRC Citation2014; Burchell Citation2015).

Science Communication Training (SCT) is defined here as an initiative that endeavours to teach some aspects of science communication to its participants – whether it includes theoretical concepts, practical skills or a mix of both. As noted by Baram-Tsabari and Lewenstein (Citation2017), such SCT initiatives can comprise a ‘once-off’ class, week-long practicums, short courses integrated into accredited institutions or full degree programmes. Most SCT initiatives aim to improve their participants’ ability to communicate their science topic effectively to their intended audience (Baram-Tsabari and Lewenstein Citation2017; McHugh et al. Citation2019).

Scientists receiving SCT have cited increased self-confidence (Gillian-Daniel, Taylor, and Gillian-Daniel Citation2020; Seakins and Fitzsimmons Citation2020; Silva and Bultitude Citation2009), increased competence in general language skills (Silva and Bultitude Citation2009), and were also observed to use less jargon in their science explanations (Yonai and Blonder Citation2020). Whilst many SCT initiatives include opportunities to practice using role-play, discussions and rehearsals, few include authentic structured spaces to practice. ‘Authentic structured spaces’ are defined here as opportunities where learners can practice their new science communication skills with the targeted members of the public in a way that is guided and moderated by instructors. As a result, many studies evaluating the impact of SCT initiatives do not examine how practice within the intended space (e.g. scientists explaining scientific concepts to children) affects learners’ science communication skills.

We describe here an SCT initiative comprising four short individual modules to prepare scientists to engage in a PES event consisting of scientist–student discussion activity. Due to the current COVID-19 crisis, both the training modules and the student–scientist discussion activity were delivered online. The evaluation of the project was underpinned by the following research questions (RQs):

(RQ1): How effective was the online training in preparing the scientists for the student–scientist chat activity?

(RQ2): What was the perceived impact of the experience on scientists’ science communication skills?

2. Methodology and theoretical perspective

2.1. I’m a Cell EXPLORERS Scientist Online Chat and the Science Capital Teaching Approach

The activity and online training modules were delivered by the science education and outreach programme Cell EXPLORERS (www.cellexplorers.com). Cell EXPLORERS comprises a national network of 13 teams based in HEIs across Ireland and aims to deliver interactive science sessions to children and young people, whilst training the next generation of scientists in PES. The PES activity, called I’m a Cell EXPLORERS Scientist Online Chat (ICESOC), comprised a live 35-minute student–scientist text-based online discussion. ICESOC sessions were hosted on a website (www.cellexplorers.imascientist.ie), in collaboration with the science outreach programme I’m a Scientist Get Me Out Of Here (www.imascientist.ie).

Scientists, students and their teachers logged on to the website and entered a private chatroom, where they could send text-based messages. The platform was used only for chat discussion, without the competition aspect. The chat sessions were moderated by the lead author, and comprised six sections: Session Introduction, Meeting the Scientist, About Being a Scientist, About Me, Free Choice and Goodbye (Supplementary Figure 1). The chat moderator introduced each section and invited the students to ask relevant questions to the participating scientists. This was to ensure a wide variety of questions were asked by students and to align to different pillars of the Science Capital Teaching Approach (SCTA). For example, during the ‘About Me’ section, students were invited to ask scientists questions about their hobbies and interests. The SCTA, a social justice approach developed to improve student engagement in science (Godec, King and Archer Citation2017), was implemented in the design of the chat structure to broaden students’ ideas of scientist and scientists (Supplementary Figure 1).

2.2. The online training modules

The training was designed drawing on best practice for SCT (Jenkins, Grygorczyk, and Boecker Citation2020; Jensen and Gerber Citation2020; Silva and Bultitude Citation2009) and the SCTA (Godec, King, and Archer Citation2017). An ‘interactive book’ format was used to create four training modules, completed by participants in their own time: (1) introduction to the programme, (2) communicating science to children, (3) child protection policies and (4) ICESOC-specific training (Supplementary Figure 2). The modules had multiple interactive elements such as quizzes, drag-and-drop activities, and essay-type answers, which have been identified as being effective in successful SCT (Silva and Bultitude Citation2009).

2.3. Data collection and participant details

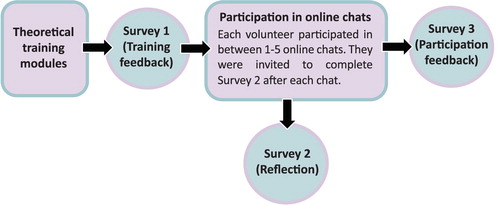

Participants were 11 scientists (8 female and 3 male scientists), from 4 different HEIs in Ireland, who volunteers with the Cell EXPLORERS programme: 5 undergraduate students, 2 research postgraduate students, 2 alumni and 3 researchers. Participants took part in up to 10 different online chats with primary and secondary students. Data were collected using surveys at three different time points (): after the initial online training (11 respondents), after each chat session (18 surveys completed; 11 respondents), and after completing the last chat (11 respondents). The surveys, comprising a mixture of open-ended questions and Likert-type scales, aimed to gather scientists’ insights into the effectiveness of the online training, the quality of the online chats and to determine the perceived impact on their science communication skills.

Figure 1. Data collection schematic. Participants completed Survey 1 (Training feedback) after doing the four online theoretical training modules. Participants completed Survey 2 (Reflection survey) after participating in each chat. Participants completed Survey 3 (Participation feedback) at the end of the project.

3. Findings and results

3.1. The online training modules were clear and informative

To determine whether the volunteers found the training to be beneficial (RQ1), responses to the training feedback (Survey 1) were analysed. Most participants agreed that the four online modules were clear and informative, were clear about the aims and objectives of the project, and felt prepared to answer children’s questions (Supplementary Figure 3). Participants seemed to appreciate the interactive elements, with all agreeing that ‘There were enough interactive elements’ for all modules. Several participants mentioned the interactive elements in open comments e.g. ‘I thought this was great – I liked the interactive nature’; ‘More interactive parts are always a good way to keep us engaged!’.

3.2. Children engaged well, but scientists struggled with the amount of questions

To explore volunteers’ perceptions of how the ICESOC sessions went, the post-chat reflection surveys (Survey 2) were examined (n = 18, not all participants completed post-chat surveys after each chat). Participants were asked ‘what went well?’, ‘what went less well?’ and ‘what could be improved for next time?’. Most (n = 12) mentioned ‘children engagement’ as the aspect that went ‘most well’ e.g. ‘the children seemed engaged with chatting to us and had good questions about what it means to be a scientist’. For ‘what went less well’ many participants reported not being able to answer the questions due to the high volume e.g. ‘I was a bit overwhelmed with the amount of questions being sent’. For ‘what could be improved for next time’, participants suggested limiting the number of questions to help address this.

3.3. Scientists reported perceived improvements to science communication skills

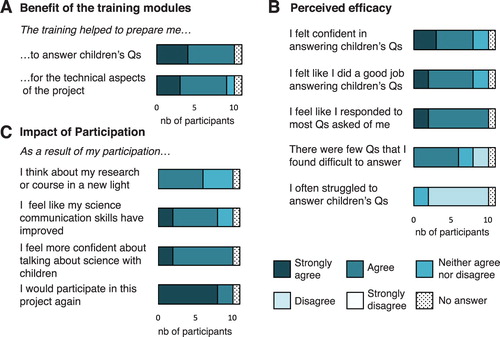

To explore the overall volunteer experience in the project, the first half of the post-project survey (Survey 3) asked participants to rate 11 Likert-type statements assessing (i) the perceived benefit of the training modules, (ii) their perceived efficacy and (iii) impact of participation (). All respondents agreed that the training modules prepared them for the technical aspects of the session ((A)). Most agreed that the training modules helped to prepare them to answer children’s questions and for the technical aspects of the project ((A)). Participants reported a high level of perceived efficacy in answering children’s questions ((B)). Despite noting in Survey 2 that they faced too many questions, most disagreed that they struggled to answer children’s questions ((B)). Most participants agreed that their science communication skills had improved ((C)).

Figure 2. Volunteers’ perceived experience of the project. Responses to Likert-Type statements in post project survey (Survey 3). All (N = 11) volunteers completed Survey 3, but one volunteer skipped this section. A. Volunteer’s perceived benefit of the training modules. B. Volunteer’s perceived efficacy during the chats. C. Volunteer’s perception of benefits of participation. Q = Question.

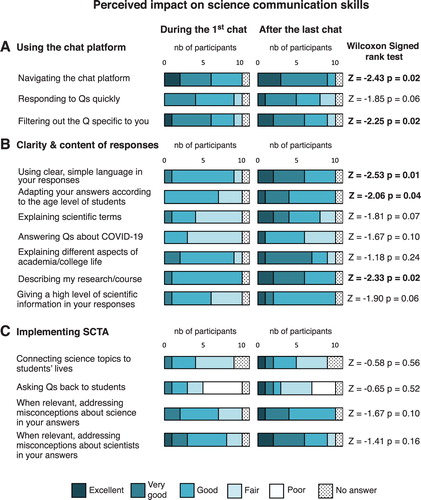

To further examine the perceived impact of participation on scientists’ perceived science communication skills, the second half of Survey 3 asked participants to retrospectively compare their competence during their first chat with how they felt after completing their last chat (). Comparing the two sets of Likert-type rankings, it seemed that participants felt that they had improved across many skills after completing their last chat, compared to during their first chat ().

To test the significance of these differences, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed. This non-parametric test compares the two sets of rankings and calculates a statistic called a Z-score: the larger the Z-score the more differences exist between the two rankings. A Z-score ±1.96 with an associated p-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Results indicated that participants perceived statistically significant improvements in five items (). Two of these items assessed participants’ perceived competence in using the online platform: ‘Navigating the chat platform’ and ‘Filtering out the question specific to you’ ((A)). This suggests that, with practice, volunteers quickly adapted to using the online platform in facilitating their interaction with students, which was necessary due to the social-distancing restrictions implemented at the time.

Figure 3. Scientists’ perceived impact on science communication skills. Scientists (n = 10/11) rated on a 5-point Likert-Type scale their perceived competence in 14 different aspects of science communication skills, as they felt they were during the 1st I’m a Cell EXPLORERS Scientist Online Chat (ICESOC) and after their last one. Comparisons between the two sets were tested using the Wilcoxon Signed rank test. Q = Question.

The item with the largest Z-score, was for ‘Using clear, simple language in your responses’ (Z = −2.53, p = 0.04, (B)), indicating that this was the skill with the biggest perceived improvement. The items with the Z-scores closest to zero were two assessing participants’ competence in implementing SCTA in answers: ‘Connecting science topics to students’ lives’, and ‘Asking questions back to students’, indicating little improvement in these skills ((C)).

4. Discussion and conclusion, including future-facing recommendations

This exploratory pilot study aimed to evaluate the impact of four online training modules and participation in a student–scientist online discussion activity on scientists’ perceived science communication skills.

The first research question was: How effective was the online training in preparing the scientists for the student–scientist chat activity? Participant feedback regarding the training was very positive: participants felt prepared to go into the discussion activity and appreciated the different embedded interactive elements. The ‘interactive book’ format served as a useful tool in delivering asynchronous training during COVID-19 social-distancing measures. Overall, the training modules were effective in preparing participants for the theoretical aspects of the activity, within the constraints of social-distancing restrictions.

The second research question was: What was the perceived impact of the experience on scientists’ science communication skills? Findings indicated that participating in the ICESOC chats positively impacted the scientists’ perceived communication skills. In particular, participants reported significant improvements in the clarity and content of their answers. Scientists also adapted well to navigating the online platform, which was necessary to facilitate such student–scientist interactions whilst COVID-19 social-distancing measures were in place.

Although the training modules included components promoting awareness of the SCTA, participants did not feel that their competence in these relating skills improved much after completing the online chat activity. One explanation for this could be that participants did not have sufficient time during the chats to try to implement the approach in their responses, suggested by their reports of receiving too many questions to answer. Alternatively, it is possible that participants were not provided with enough practical advice on how to incorporate such tactics in their responses. Moreover, participants were not given specific feedback in between chat sessions, which is an important step in learning (Kolb and Kolb Citation2005).

Future work within this project will focus on revising the online training to increase the implementation of the SCTA approach in scientists’ answers. Revisions will include adding practical tips on incorporating SCTA into responses, providing volunteers with a rubric to help reflect upon their responses and to guide future improvement, and developing a live workshop where volunteers can receive feedback from instructors on their answers to questions.

Overall, this pilot study demonstrated the importance of providing authentic structured spaces for scientists to practice their science communication skills with a real audience in a way that is guided and moderated. Whilst the scientists in this study had a positive experience of the online training, it was engaging in the PES activity itself that impacted their perceived science communication skills.

Ethical considerations

This study had approval from the research ethics committee at NUI Galway (REC: 2020.10.001). Data were only obtained from CE volunteers who provided positive informed consent.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (2 MB)Acknowledgements

This research was conducted in M.G’s research group within the Biochemistry discipline of School of Natural Sciences at the National University of Ireland Galway in Ireland. The authors thank the science outreach programme and competition I’m a Scientist Get Me Out Of Here (www.imascientist.ie) for hosting the I’m a Cell EXPLORERS Scientist Online Chat activity on their web platform, the pupils and teachers who attended the event, and the Cell EXPLORERS volunteers who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

S.C and M.G. are running the educational outreach /public engagement programme Cell EXPLORERS featured in this work. The programme is funded by Science Foundation Ireland, and supported by the Biochemistry discipline, the School of Natural Sciences, the College of Science, and NUI Galway. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1915840.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sarah Carroll

Sarah Carroll is a research associate in Biochemistry at the National University of Ireland Galway. Her current research interests are in informal science education, self-efficacy and the effect of scientist-facilitated outreach on young people’s perceptions of science and scientists.

Muriel Grenon

Muriel Grenon is a lecturer in Biochemistry at the National University of Ireland Galway. Her current research interests are in informal science education, hands-on learning and the use of educational science outreach as a university teaching tool.

References

- Baram-Tsabari, Ayelet, and Bruce V. Lewenstein. 2017. “Science Communication Training: What Are We Trying to Teach?” International Journal of Science Education, Part B 7 (3): 285–300. doi:10.1080/21548455.2017.1303756.

- BBSRC. 2014. “Public Engagement and Science Communication Survey Report 2014.” https://bbsrc.ukri.org/documents/pe-and-science-comm-report-pdf/.

- Besley, John C., Anthony Dudo, Shupei Yuan, and Frank Lawrence. 2018. “Understanding Scientists’ Willingness to Engage.” Science Communication 40 (5): 559–590. doi:10.1177/1075547018786561.

- Brownell, Sara E., Jordan V. Price, and Lawrence Steinman. 2013. “Science Communication to the General Public: Why We Need to Teach Undergraduate and Graduate Students This Skills as Part of Their Formal Scientific Training.” Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education (JUNE) 12 (1): E6–E10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3852879/.

- Burchell, Kevin. 2015. “Factors Affecting Public Engagement by Researchers.” https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/wtp060033_0.pdf.

- Campus Engage Charter. 2014. “Campus Engage Charter for Civic and Community Engagement.” https://www.campusengage.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Charter_image_1_.png.

- Clark, Greg, Josh Russell, Peter Enyeart, Brant Gracia, Aimee Wessel, Inga Jarmoskaite, Damon Polioudakis, et al. 2016. “Science Educational Outreach Programs That Benefit Students and Scientists.” PLoS Biology 14 (2): 1–8. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002368.

- Concannon, C., and M. Grenon. 2016. “Researchers: Share Your Passion for Science!.” Biochemical Society Transactions 44 (5): 1507–1515. doi:10.1042/BST20160086.

- European Commission. 2002. “Science and Society: Action Plan.” http://www.asset-scienceinsociety.eu/pages/science-and-society-action-plan.

- Gillian-Daniel, Anne Lynn, Benjamin L. Taylor, and Donald L. Gillian-Daniel. 2020. “Using Improvision to Increase Graduate Students’ Communication Self-efficacy.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 52 (4): 46–52. doi:10.1080/00091383.2020.1794262.

- Godec, S., H. King, and L. Archer. 2017. “The Science Capital Teaching Approach.” https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10080166/1/the-science-capital-teaching-approach-pack-for-teachers.pdf.

- Hunt, Colin. 2011. “National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030.” https://www.education.ie/en/publications/policy-reports/national-strategy-for-higher-education-2030.pdf.

- Jenkins, Amy Elizabeth, Alexandra Grygorczyk, and Andreas Boecker. 2020. “Science Communication : Synthesis of Research Findings and Practical Advice from Experienced Communicators.” Journal of Extension 58 (4): 1–10. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol58/iss4/1.

- Jensen, Eric A., and Alexander Gerber. 2020. “Evidence-Based Science Communication.” Frontiers in Communication 4 (January): 1–5. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00078.

- Kolb, Alice Y., and David A. Kolb. 2005. “Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education.” Academy of Management Learning and Education 4 (2): 193–212. doi:10.5465/AMLE.2005.17268566.

- Laursen, Sandra, Carrie Liston, Heather Thiry, and Julie Graf. 2007. “What Good Is a Scientist in the Classroom? Participant Outcomes and Program Design Features for a Short-duration Science Outreach Intervention in K-12 Classrooms.” CBE Life Sciences Education. doi:10.1187/cbe.06-05-0165.

- McHugh, Martin, Sarah Hayes, Aimee Stapleton, and Felix M Ho. 2019. “RAW Communications and Engagement (RACE): Teaching Science Communication Through Modular Design.” In Research and Practice in Chemistry Education, 185–202. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-6998-8_12.

- Seakins, Amy, and Alexandra G. Fitzsimmons. 2020. “Mind the Gap: Can a Professional Development Programme Build a University’s Public Engagement Community?.” Research for All 4 (2): 291–309. doi:10.14324/rfa.04.2.11.

- Silva, Joana, and Karen Bultitude. 2009. “Best Practice in Communications Training for Public Engagement with Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics.” Journal of Science Communication 8 (2): 1–13. doi:10.22323/2.08020203.

- Thomas, G., and J. Durant.1987. “Why should We Promote the Public Understanding of Science?” In Scientific Literacy Papers, edited by M. Shortland, 1–14. Oxford: Rewley House.

- Yonai, Ella, and Ron Blonder. 2020. “USE YOUR OWN WORDS! Developing Science Communication Skills of NST Experts in a Guided Discourse.” International Journal of Science Education, Part B 10 (1): 51–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2020.1719287.