ABSTRACT

The impact of State policy to combat educational disadvantage with two iterations of DEIS supports has had a positive influence the patterns of achievement among all social groups with some notable improvements across a range of indicators for students in DEIS schools. Notwithstanding these improvements, research and evaluations continue to identify a persistent achievement gap for large numbers of working-class students compared to their more middle-class peers. Research evidences the inextricable links between class, economic circumstances, and student outcomes. In producing these more system-oriented data, the dynamism of underlying processes that produces these outcomes can be often masked. Student-teacher characteristics and classroom interactions become variables or aggregated performance datasets, rather than signifiers to unpack the mechanisms of how students and teachers construct their classroom world. Pedagogic communication, so central to classroom teaching and learning, is largely unexplored from the perspective of its construction, transmission, acquisition, context and how these are framed by structures of social relationships. This paper intends to explicate a core component of the student/school relational domain by examining specifically the patterns of pedagogic communication that frame teaching and learning in one case study school located in a very marginalised and challenging community in Ireland. The findings are stark. Different linguistic strategies for engaging in pedagogic communication are detailed in the data but in all cases, they fail to lead to rich learning experiences and positive student outcomes.

Introduction

The impact of State policy to combat educational disadvantage with two iterations of DEIS supports (2007, 2017) has had a positive influence on patterns of achievement among all social groups with some notable improvements across a range of indicators for students in DEIS schools (Weir and Kavanagh Citation2018). Notwithstanding these improvements, research and evaluations continue to identify a persistent achievement gap for numerous working-class students compared to their more middle-class peers. Many of these gaps may now be compounded and it is also likely that the identified gains (Weir and Kavanagh Citation2018) will be eroded by sub-optimal experiences and significant disruption to learning during COVID 19 (Flynn et al. Citation2021; UN Citation2020; ESRI Citation2020). Achievement gaps for most working-class students have persisted across all the indicators used in the literature to define educational success in class comparative terms, e.g. grade attainment, school completion, graduation, progression and career trajectories. Indicators are expressed in terms of aggregated outcomes, densities, distributions, socio-economic identifiers and classroom transmission in terms of management and administrative systems. The educational stratification revealed by the research ‘describes the systematic structures of inequality’ (Crompton Citation2008) and draws attention to the inextricable links between class, economic circumstances and outcomes. Many outcome-focused studies evidence ‘a state of knowledge’ rather than ‘ways of knowing’ (Bernstein Citation1971, 214), and the dynamism of underlying processes is masked by this rationalist, performative approach. Student-teacher characteristics and classroom interactions become variables or aggregated performance datasets, rather than signifiers with the potential to unpack the mechanisms of how students and teachers construct their classroom world. Pedagogic communication, so central to classroom teaching and learning, is largely unexplored from the perspective of its construction, transmission, acquisition, context and the principles of ‘their embodiment in structures of social relationships’ (Bernstein Citation1973). More recent work on establishing links between building school belonging in adolescence and school success (Korpershoek et al. Citation2020) foregrounds the social relationships that frame classroom interactions as a key prerequisite for success. Evidence has also found that there are very clear, and by now well-established, negative correlations between lower SES groups and their sense of belonging, which, in turn, is significantly associated with several motivation-related measures—the expectancy of success, valuing schoolwork, general school motivation and self-reported effort (Goodenow and Grady Citation1993). The seminal work of Bernstein, Bourdieu and many who have drawn on their conceptual strengths about the inequity of experiences of working-class students in school now resonates with these more recent ideas of belonging and self-efficacy. This paper intends to explicate the core of the student/school relational domain by examining specifically the patterns of pedagogic communication that frame teaching and learning in one case study school located in a very marginalised and challenging community in Ireland.

Some theoretical insights

The potential ‘usefulness’ of examining how students and teachers respond to and interact with and within the material and immaterial environment of the classroom, is based on the premise that ‘the way we signify the world is at least partially constitutive of that world’ (Quantz Citation1999, 494). These signifiers are embedded in the myriads of small, daily patterned actions of classroom interaction as teachers and students navigate the effects of their structural biographies and deploy their cultural resources to negotiate the school space’s legitimated norms and conventions. To release the ‘interpretative usefulness’ (Quantz Citation1999, 494.) of this process it is necessary to engage with, strip back and understanding ‘the complex local ecology’ (Luke Citation2018, 3; Mac Ruairc Citation2009, Citation2011a, Citation2011b) of school classrooms, ensuring the social relationships which this process rests upon are not abstracted from the wider social and cultural situation (Bernstein Citation1977, 23). Central to this process is language in its many forms and manifestations. Language enters the classroom and mediates teaching and learning in many different ways. Insights into the complexity and centrality of language in classrooms are increasingly emerging in research. Recent work on multilingualism, translanguage, language-sensitive classroom practices and other work in critical and culturally appropriate pedagogies are among this scholarship. However, some of the more persistent and chronic issues relating to language in the classroom represent the focus of this paper. This focus on language will concentrate on the well-established view that working-class students are embedded in discontinuous cultural and linguistic relational domains for the cultural and linguistic norms of school and those norms that prevail outside the school context. These perspectives continue to be reaffirmed by many scholars especially those working on the impact of social class and educational outcomes (Reay Citation2006; Reay, Crozier, and James Citation2011; Bader, Lareau, and Evans Citation2019). Layered onto and into this broader phenomenon is an examination of pedagogic communication and pedagogic discourse (Bernstein Citation1990) that gives primacy to the knowledge we have about the central role language plays in mediating student learning. Perspectives on pedagogy that come from a range of different perspectives explicate how high-quality critical discussions form the basis for efficacious teaching and learning. In essence, the paper follows the core class-based discontinuity that permeates the overall experiences of school for many working-class students in the classroom focusing on all of the linguistically derived relational norms and practices that delimit this space.

Language in context

The context of school endows a specialised character on ritualised interactions that can be understood as ‘aspects of social action that are formalised, symbolic performances’ (Quantz Citation2011, 119), whose meaning also transcends the ‘specific situational meanings’ (Bernstein Citation1975/Citation1977, 54). It is also necessary that the social relationships on which this process rests are not abstracted from the wider social and cultural situation (Bernstein Citation1971, 23). While the core of this study is concerned with teaching and learning school knowledge in the formal setting of the classroom, it is also in search of the socially based, symbolic processes operating beyond the situated actions of the classroom, which mediate the biographical consciousness and differentially shape the school knowledge orientations of classroom participants through the enacted processes of their socialisation. To realise this objective, this paper aspires to examine the pedagogic consequences of some of the ways ‘relations to’ and ‘relations within’ shape classroom pedagogic practices for working-class children’s access to their democratic entitlement to ‘pedagogic rights’ (Bernstein Citation2000, xxi). This approach generates general principles that are ‘somewhat wider than the relationships that go on in schools … a fundamental social context through which cultural production and reproduction takes place’ (Bernstein Citation2000, 3).

Pedagogic communication/pedagogic discourse

Placing pedagogic communication at the core of the process of teaching and learning foregrounds many forms of classroom discourse and points to the dialogic nature of classroom practice as developed in Bernstein’s concept of enhancement and the Bakhtinian concept of the dialogic (Bakhtin Citation1984) for the development of student critical thinking and overall high-quality engaged learning. Bakhtin proposes dialogue as a route to critical engagement, to experiencing new horizons and a route to accessing new possibilities referenced in Bernstein’s yet to be thought of. Bakhtin outlines the process as

An active understanding, one that assimilates the word under consideration into a new conceptual system, that of striving to understand, establishes a series of complex interrelationships, consonances and dissonances with the word and enriches it with new elements (Bakhtin Citation1984, 282)

Bakhtin’s concept of dialogue involves more than a conversational exchange of words. It is based on the Socratic idea of dialogue involving syncrisis (juxtaposing) and anacrisis (provocation) (Bakhtin Citation1984). The rationale underpinning this concept is the notion of polophony, (multivoicedness) involving the interaction and interdependence of different levels of consciousness, yet each consciousness has equal rights, retaining a separateness and preserving its uniqueness:

A plurality of independent and unmerged voices and consciousness’s, a genuine polophony of fully valid voices … a plurality of consciousness’s, with equal rights and each with its own world, combine but not merge in the event. (Bakhtin Citation1984, 8, 72)

This points to the need to develop a very high level of classroom discourse to create the circumstances for this type of dialogue to happen. The alignment of this type of classroom culture in creating optimal circumstances for learning and developing a better sense of belonging for students is widely recognised.

To a large degree, Bakhtin’s dialogic sets out an ideal type of context for learning. If this context and the pedagogic processes within it are examined using Bernstein’s concept of classification and framing, it becomes possible to see key junctures where teaching and learning can be shaped and formed in different ways as discursive outcomes of practices. Classification and framing are theoretical concepts that attempt to specify the nature of the rules, transmitters and acquirers we are expected to learn if they are to produce what counts as legitimate meanings and legitimate realisation in relevant contexts (Bernstein Citation1990, 127). The concepts of classification and framing are concerned with power and control. Bernstein distinguishes these concepts analytically to provide a model which separates ‘discourse from the form of its transmission and evaluation’ (Bernstein Citation2000, 99), although, in practice, these concepts are embedded in each other. Concepts of classification and framing make us understand the social nature of formal pedagogic discourse construction and the potentially totalising nature of the external macro- and internal micro-level control of transmission and acquisition and the relation between the micro and macro.

Together, classification and framing offer insights into the ‘privileging text’ (Bernstein Citation1990, 176) of institutionalised formal schooling and a conceptual language to describe this process. Pedagogic communication is embedded in the principles of classification and framing, in terms of legitimacy, orientation to meaning, subject voice/message and specialised interactional practices (Bernstein Citation1996). Classification defines the context, provides and delimits voice/discourse/identity, constructs the rules and procedures of its recognition, ‘the order of things’ and the means of recognition of legitimate message. Framing regulates relations between acquirers and transmitters, within an already defined context, establishes the message (practice), produces the discourse and actualises a means of realising what is to be recognised as legitimate text and enables its attainment. Together, classification and framing regulate the ‘distinguishing features’ of communicative contexts, creating, defining and legitimising the specialised practices required to produce the ‘syntax for generating legitimate meaning … [and] … the syntax of realization’. This presupposes concepts of appropriate/ inappropriate forms of realisations through legitimate/illegitimate communications (Bernstein Citation1996):

Classification refers to what, framing is concerned with how meanings are to be put together, the form by which they are to be made public, and the nature of the social relationships that go with it’ (emphases original, Bernstein Citation2000, 12)

The insight then an examination of framing brings to a critical examination of pedagogic communication and pedagogic discourse is notable. Bernstein’s concept of framing can be defined as the control of the ‘internal logic’ of the interactional principle within the pedagogic communication context (Bernstein Citation2000, 12). Framing operates as a structuring mechanism of pedagogic practice by controlling communication within the local pedagogic setting, legitimising and regulating pedagogic relations, talk and spaces. Framing can be either strong or weak across the elements of practice. Strong framing represents transmitter control of context and the rules of regulative and instructional discourse are explicit. Weak framing represents implicit regulative and instructional discourse and is largely unknown to the acquirer. Framing creates the realisation rules and regulates the means of acquiring what counts as legitimated text by controlling the following instructional dimensions of the pedagogic context:

The social base which makes the transmission possible

Selection of the communication

Sequencing

Pacing criteria (Bernstein Citation2000, 12–13)

Framing is concerned with ‘how meanings are to be put together, the form by which they are to be made public, and the nature of the social relationship that go with it’ (Bernstein Citation2000, 12). It is Bernstein’s view that within the school the instructional discourses of classrooms are always embedded in the overall regulative discourse. This in itself may well point to a fundamental fault line in the overall school system where students have to be regulated to learn. What is important in the case of this paper are two key factors that will examine the level of embeddedness of the instructional in the regulation and the related degree of dominance of the regulative over the instructional.

Methodology

This research was carried out in one case study second-level school, located in an urban area considered economically and socially disadvantaged since the school was established. The area is identified as one of the most disadvantaged urban areas at the national level as determined by a very useful deprivation index, based on CSO statistics – (Hasse and Pratschke Citation2014). details this designation based on this index:

Table 1. Deprivation index of school area.

The shaping of this inquiry is filtered through the researcher’s biographical lens shaped by 30 years’ teaching experience, mostly in the case study school, and always in schools in marginalised communities, which undoubtedly contributes a degree of ‘insider’ knowledge and accompanying bias. This positioning of the researcher in the study is a transactional strength and a weakness. Familiarity with the research site characteristics obviates a need for immersion in context. It also requires ‘critical vigilance’ (Derrida Citation1987), to prevent interpretative distortion through personal biases (Creswell Citation2003). Due to the researcher’s association with the characteristics of the research, it was essential to making the familiar ‘anthropologically strange’ (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). As the research process unfolded during the data collection phase of the study this ‘strangeness’ was achieved by clear and repeated communication with all parties as to the purposes of the study. Over time the shift from an insider, as a teacher, to an outside storyteller, as a researcher, was understood and welcomed by participants; there was a sense that if anyone is to tell this story then it should be this researcher -a kind of ‘who knows us better’ perspective.

At the outset it is important to point out a clear finding borne out by this study in relation to the strengths of a single research site that does not signify a more simplified research study. Within the single case study school, there are multiple of cases, at class year group, ability streaming, subject, student, teacher and parent level. Each of these subcases provides an additional data dimension. The accumulation of different experiences and potentially differing perspectives and orientations to meaning adds another layer of complexity, of interrelationships and interconnections.

The study adopted an ethnographic stance following the steps of Bronislaw Malinowski, a giant of ethnographic research, by engaging in prolonged immersion as a participant at the research site. The rationale for this was to attempt to enter the study participants’ worlds and abstract how their experiences were constructed in day-to-day interactions. Immersion in the participants’ ‘own turf’ facilitated a search for meaning and tacit understanding in participant actions and practices. The study situates knowledge as socially constructed, relational conversational, contextual, linguistic, narrative and pragmatic (Kvale Citation2007, 54–56). From a social constructivist perspective people are viewed as ‘constructing the social world, both through their interpretation of it and through the actions based on those interpretations’ (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). This positioning does not fit neatly into any one bounded methodological paradigm. It is grounded in postmodern thinking in terms of a rejection of a universal system of thought, of economic performativity and mercantilisation of knowledge (Lyotard Citation1984) viewing reality through, ‘interpretation and negotiation of meanings of the social world’. Adoption of this worldview of social action provides the potential to gain insights into the culture of the researched subjects. Observing their actions and hearing their accounts of how they experience events can open a means of access to their interpretation of the world and how they construct meaning in relation to it. Hammersley and Atkinson observe:

We act in the social world, and yet we are able to reflect upon ourselves and our actions as objects in that world … capacities we have developed as social actors can give us such access … we can interpret the world more or less in the same way … we can produce accounts of the social world and justify them. (Citation2007, 10–18)

The ethnographic perspective of this study is based on a ‘pragmatism that ideas and meanings derive their legitimacy from enabling us to cope with the world in which we find ourselves’ (Kvale Citation2007, 52–56).

Three main methodologies were used in collecting data for this case study:

Participant interviews (students (n = 15), teachers (n = 8), and parents (n = 10);

Multiple, sequential classroom observations in the eight classrooms of teacher interviewees, and/or many single observations in classes of other teachers not involved in interviews;

School documents (School Discipline Policy, student attendance records and school journals of two students and a selection of standardised school–home letters).

Findings

The findings presented below are stark. They present a picture of pedagogic communication that is so tightly framed that it offers a little by way of extended learning opportunities and produces largely negative and disruptive forms of classroom discourse. The language code that prevails in the classrooms, specifically using directive and controlling language, frames all aspects of classroom interaction with negative consequences for the overall efficacy of teaching and the quality and type of learning. A key driver of these practices is a view of student behaviour, articulated through a discourse, that is benchmarked against the schools' values, norms and goals for teaching and learning. This ideal construct of engagement with school norms, which the data below reveals, functions as an alienating force in classrooms. The data presented here illustrate examples of classroom interactions that were observed in all eight classrooms and discussed by all participating teachers, students and many parents during interviews. The purpose is to present vignettes of classroom practice that foreground the type of pedagogic communication that typically occurs in this case study school. They draw on student perspectives mainly but not exclusively. Future publications based on this study will highlight how teachers strive to manage the pedagogic communication in classrooms and how they attempt to frame pedagogic communication more weakly to create more collaborative, democratic-type learning environments for students. This is not a blame game; it is an account of a class-based, linguistic struggle in schools that follows in a long line of calls for radical action– no more no less.

The case study school sets and explicates norms considered facilitative for student achievement. These norms require regular student attendance, punctuality, observance of the school’s code of conduct and teacher/subject-specific stipulations/requirements for the management of safe, respectful and effective classroom engagement. The language used here is unidirectional – a clear code with no room for manoeuvre despite the clear gaps between the code and the lack of control the code exerts in practice ().

Table 2. Research school code of conduct.

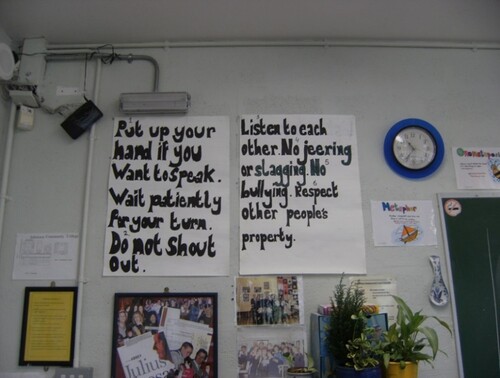

An additional set of rules governing the linguistic interactions that are permitted are on display in many classrooms in the school. These follow a similar tone with a few options for the type of classroom discussions that lend themselves to high-quality learning conversations ().

There is no ambiguity about the message in this notice. The framing is very strong; the font used is bold, emphatic, and large enough to be read with ease from the back of the room. The modality of the text, ‘Put up, Wait, Do not, Listen’ is direct and commanding, indicating an authoritative source (Fairclough Citation2001). The message in the notice urges interactional distancing by adopting social routines that constrain interpersonal relations. They can act as constraints on communication and collaboration. These routines of politeness are expected and considered necessary in the classroom. Fairclough considers politeness as a manifestation of formality based on a relational exercise of power, intended to control through distancing. The politeness routines, e.g. of signalling intent and waiting turns, induce a degree of formality to the classroom through stable, routine practices, which some students seem to find difficult or choose not to comply with.

Classroom observation by the researcher indicates that a few students overtly interact with teaching and this appears to confirm statements from students, teachers and parents about how few students engage. Only 2–3 students volunteer to answer teacher questions, indicating their willingness by raising hands. The silence of otherwise committed students is notable. In each classroom, the pattern is repeated. It is generally the same few students who offer and in some classes, there was only a single student engaging in this mode of interaction. In most classes observed there were no student-initiated questions apart from a small number of procedural ones, e.g. ‘what page are we on?’. Some of the students have internalised the code and complied – the issue is to what end? These student participants heavily subscribed to listening in class. Students are considered to be ‘good learners’ when they attend school regularly, are silent in class and concentrate on listening to the teacher; students who cooperate and complete classroom tasks, retain information and do homework assignments. A mix of both engaged and disengaged students describe these attributes:

: A good learner is someone who listens in class and remembers everything

: Concentrates … listens to the teacher

: Mostly some people that are like, geeks. They pay more attention, teachers know that they know the answers because they’re always in all the time … they always do their homework, and they are always good and they never talk.

: A good listener, co-operating

In each of the classes observed and among many of the students interviewed some students ignore the polite conventions expected in the classroom. These students are not always disinterested in school or learning; they do not always have low expectations of themselves but they share the patterns of classroom interactions with those who deliberately resist. Typically, these students do not raise their hands to request teacher assistance or wait patiently to be nominated to speak by the teacher. They shout out in class to command teacher or peer attention. Their method of inquiry is loud, noisy, insistent, persistent and urgent. They make their expectation of immediate teacher response explicit. These students resolutely engage to achieve classroom-learning objectives while simultaneously flouting the rules for student engagement. While their behaviour is an earnest request for assistance, their conduct is disorderly and diverts teacher and student attention from teaching and learning. This is public form of oppositional behaviour.

Student Audrey typifies this type of student style of communication. She claims, ‘I’m the type of person … if I didn’t know how to do something I’d say it like, here I don’t know how to do that like’. This excerpt from Audrey’s interview displays her resolve in seeking guidance/clarification in class when she does not understand the next steps. Her approach is straightforward and upfront. Audrey states that if she doesn’t know how to do something she will ask. She is not prepared to ‘sit at the back of the class being quiet and not having a clue’. Her objective to be well informed is linked to her aspiration and rationale for achieving a high standard in her exams. She views this as a means to achieving economic success and personal independence.

Student Audrey:

I want to do all higher levels like. I’d like to do all, because I’d be proud of myself. Like ordinary level in some things, probably like one or two would be alright, but I want to do higher level in most things … I don’t want to be sitting around like everyone else in … town. Like being on the dole or whatever they’re on, like on the labour, living off social welfare. I want to have a job and a big nice house, and a nice family and a nice sports car I don’t want to be driving around on the dole with a little Nissan, I want to have something more for me future, ‘cos the best part of jobs you need good education.

This stimulates her belief in her capacity to engage and scaffolds her confidence to ask questions in the public environment of the classroom; openly acknowledging her failure to comprehend. The honesty of this common-sense approach implies a sense of entitlement that access to school knowledge is her due as a student.

Student Audrey uses the term, ‘here’ to attract the teacher’s attention. This could perhaps be viewed as an expression she might use with a peer outside the formal context of the class. It has an informal edge to it and young people use it to preface an address to a peer, as in ‘here you’. It could also be interpreted as having an element of the command, as in ‘come here’, indicating her expectation of the teacher’s role in guiding students and student entitlement to receive assistance. Audrey’s behaviour may indicate her perception of adult–child relationships as undifferentiated, regardless of role, teacher–student levels of maturity or context-appropriate codes. It denotes student challenge to the hierarchical teacher–student power classroom relationship, even if not intended as power inversion by Audrey.

Researcher observation of student Audrey interacting with her mother at their home revealed the child appeared to see herself on a par with her mother, communicating with her on equal footing, demonstrating a strong sense of her entitlement to hold and voice opinions and an expectation of her contribution being regarded as equally valid as an adult’s. This adult–child parity, observed in the home does not correspond with classroom communication codes for deference to adults who are invested with authority. Parent Audrey, commenting on her child’s forthright disposition and interactional style noted:

She needs to shut her mouth, stop mouthing out of her as well. She is like that here with me. If she thinks she is right she won’t stop, she will not stop for a minute ‘til she has had her say. She doesn’t realise she is being cheeky, seriously that’s the truth where adults would say, Jesus, she is so loud. If she wants to get her point across, she will roar at the top of her voice. She doesn’t realise and I say to her, Audrey you are shouting at me.

During the interview, parent Audrey suggested to her daughter, ‘you’d want to start changing, stop carrying on in school’. Audrey became defensive and answered her mother in a raised angry voice:

Audrey: Carry on what way ma? If someone is roaring in my face, giving me cheek, I am going to roar back and that’s only human and that’s the way I am. I won’t let anyone give me cheek. I don’t care what anybody thinks. She said I come across as too fiery and that it’s not fair on the other students. I won’t change. I like the way I am. I won’t change it for nothing and if you don’t like me, you don’t like me.

Parent Audrey: Well, tone it down or something

Audrey: I’m not changing I told the Miss the other day that I am not changing. How is it not fair that I have a good personality?

In this extract, student Audrey is adamant that she will not change to accommodate the teacher’s idea of appropriate school behaviour. Yet her very varied behaviour and demeanour in school is inconsistent with this statement. In teacher David’s class she is school compliant, a model student, never in trouble, never creating any disturbance, working hard and achieving good grades. In teacher Martha’s class, she usurps the teacher's time and attention, does not engage with the subject, fails the subject in examinations and renders the class inoperable. Classroom observation and her interviews attest to this. Her interviews reveal this pattern is repeated in other classes. Two key influences emerge from her interviews as possible explanations. Her affinity and understanding of subjects influence her engagement. This is linked to her relationship with the subject teacher, which in turn is shaped by her perception of the teacher's academic competence and social attributes:

Student Audrey: Like teachers do get cheeky with you, like everybody thinks teachers don’t … .if someone gives you cheek it’s only natural to give them cheek back. That’s the way it works. Because if someone comes in and is disrespectful for you, would you not give them any respect back? Obviously you’re not going to. Because I don’t … but like obviously if a teacher gives you cheek you’re going to give them cheek back … I find that teachers in this school that has respect for you and doesn’t give you cheek unless you give them cheek, and listens to you.

Despite Audrey’s angry protestation about not changing, she has tried on previous occasions to fit in with school requirements:

Student Audrey: I tried to just, sit down and don’t say anything back, but I can’t though. I really can’t do that. I really can’t, if someone says something to me I have to say something back. It’s just me, I’ve tried it. I’m just not one of those people to keep things to themselves.

‘Miss, Miss, Miss’

Repetitive calling of ‘Miss, Miss Miss’ for assistance irritates and annoys teachers. It reflects a breach of classroom politeness. The noisiness encroaches on the classroom quietness some teachers feel necessary for effective classroom communication. Requests for students to ‘be quiet, to s-h-hush, to listen up, pay attention’ in conjunction with the Initiation-Response-Feedback (IRF) methodology, are regularly used by teachers during a classroom observation. The shouting out of turn could be regarded as distracting from students' focus on the teacher, which is central to IRF. Teachers may also be concerned about interference with student peer contribution engagement.

Some teachers feel constant calling out makes unreasonable demands on the teacher, especially where many students are calling out contemporaneously. They consider it may demonstrate a student lack of understanding of the complexity of the teacher’s role in the classroom, especially if the class size is large. Teacher Julia attributes students' inconsiderate behaviour result of their impatience rather than a lack of awareness of what is appropriate:

Teacher Julia

Even if the hand goes up … The whole idea of waiting, that it's not instantaneous … Where maybe at home, they ask and they get, or they don't have to wait, to put other people first. As I said I think they know for the most part how to behave and the know when they are acting up. And my thing there is just that the impatience sometimes, you know

Teacher Julia strongly expresses her belief that students are aware of what counts as context-appropriate behaviour and are selective in how they exercise it in different contexts and conditions. She considers they make deliberate choices. She supports her claim by referencing how she has observed students’ varied behaviour in school across different classes and their capacity to act per context requirements outside school:

Teacher Julia

But I’ve been struck by, over the years, that students do know, they’re very astute in different situations how to behave … and eh, within the school day, from teacher to teacher, they might choose to behave in one way and another way. I’ve seen very, very difficult students over the year, very challenging students, who might have a job and they’re in Mc Donald’s or whatever and they would know how to ‘tow the line’ down there with the manager, so I think they do pick and choose, I think they are aware what is correct behaviour, for the most part.

In this account, students’ raising a hand for teacher attention indicates their awareness of required compliance, albeit only partially practised. However, it is not accompanied by silent waiting for the teacher’s response or teacher’s permission to contribute, which teacher Julia attributes to the student’s impatience. An alternative perspective might regard student ‘calling out’ as an indication of eagerness to engage, despite the insensitivity towards other classroom participants learning needs. They do not appear to be acting as a cohesive group but seem to be simultaneously but independently seeking teacher or peer support in relation to a classroom task. While it is a deliberate tactic, it does not appear to be planned. It seems to happen, to be necessitated by the requirements of the moment as these students spontaneously call out for assistance. Their calling out fractures the sense of order, valued in the classroom and considered by teachers and students as conducive to teaching and learning. They can dominate the classroom, depending on the teacher’s reaction and/or how these students interpret the teacher’s reaction. If the teacher’s attention does not measure up to their entitlement expectations or if they consider that the teacher is providing an inequitable amount of time to other students, their behaviour is liable to explode.

Wait time

Some examples of these extreme outbursts detailed below appear to be linked to this type of delayed response by the teacher. If the waiting time for the teacher’s response is too long, frustration ensues and builds, tolerance runs out and students become exasperated. They give up on seeking assistance and channel their attention elsewhere. Some students recount teacher preparedness to assist them, ‘if I'm stuck teachers come over and explain it’. Despite students’ recognition of this, students are annoyed at the perceived delay in teachers’ responses.

Student Dominic: You’d be calling her like that, going Miss, Miss, Miss

Student Jasmine: Will you hurry up then miss; you are helping them and not me.

Student Hayley: In some classes, teachers don’t come over to you straight away.

Student Hilary recounts the wait time for some teachers’ responses as excessive. The teacher’s response is to eventually remove the student from class. The cooling-off period is supposed to be for ‘five’ [minutes], but Hilary is excluded for the entire class period despite her requests to return:

Student Hilary: … and sometimes they leave you waiting for ages and then I get annoyed and the miss would tell me to take five. Take five ends up the whole class because they just don’t come out and get you. … Yeah, I do [ knock on door and request to return] and they just tell me to get out until they call me … Yeah but they don’t call me till the end of class, all of them.

The outcome of this encounter for Hilary fails to provide her with the desired assistance, but she is also excluded by the teacher from participating in-class instruction for the entire class period.

Other students exclude themselves to highlight their dissatisfaction with the teacher’s behaviour. They are angered by having to wait ‘for ages’ for the teacher’s assistance. Their ire is vented in eruptive behaviour, slamming work on the desk or the ground, swearing, remonstrating, refusing to continue with the task in hand or stomping from the room and banging the door on the way out. They are transferring the responsibility for their disengagement to the teacher. They may consider withholding effort and/or abandoning tasks punishes the teacher:

Teacher Clarissa: They say … ‘Miss, You never come over and I’ve been waiting for ages’ This can escalate to a situation where stuff gets thrown up in the air because you don’t get there fast enough … or they would down tools and tell you, I’m not doing it now because you didn’t come over to me. I am not doing any more of this. Just a kind of a sulk situation … throw work on ground, stalk out and slam door.

Student Dominic recounts an incident where one teacher interprets his efforts to seek teacher assistance as ‘talking out of turn’. He recounts what he considers deliberate and selective ignoring by a teacher. He claims she is unresponsive to his initial appeals for help. Instead, the teacher informs him of his lack of compliance with the classroom protocol of hand raising to signal a student wishes to speak. The student recounts the teacher also ‘ticks’ him on a misdemeanour record. The student appears to accept this action. His reference to ‘talking out of turn’ demonstrates awareness of classroom interaction requirements. His acceptance, without remonstration, of the ‘tick’ indicates he most likely understands it as a consequence of a breach of the class rules. Being informed of this protocol infringement may lead the student to interpret this as the reason the teacher does not assist. He adjusts his method of attracting teacher assistance by raising his hand to conform to the teacher’s requirements. He waits for what he says feels like an hour to get a response and still does not succeed. Feeling defeated in his efforts he stops trying. His frustration at his helplessness to affect the teacher’s attention finds expression in expletives. He observes that at this point his swearing merits her attention, negatively. The student is indignant at the teacher’s focus on his swearing. He is incensed by her silence to his request to ascertain what she is ‘ticking’ on his record. He challenges the teacher. The student’s action merits another ‘tick’. He challenges again. Each challenge receives yet another ‘tick’, but the teacher remains silent, except to request the student to leave the classroom.

Student Dominic: When you talk, when you talk out of turn and you say Miss will you help me with this, she’d tick you and say you didn’t put your hand up. You put your hand up and you’re waiting for about an hour … and a few would have their hands up … she wouldn’t listen and you put your hand down and say, if you go like that, f—- sake. She put you, she ticks your name down … She wouldn’t hear you calling her but when you curse you get put down. Then when she puts you, when she puts the tick down then you’d being having a big argument and she’d send you out … She wouldn’t say anything back, she’d just go like that. Tick down. And say what’s the other tick for and then she’d … put another tick down, keep going with the ticks … She still doesn’t answer

The outcome of this student-teacher interaction is negative attention rather than the assistance Dominic had originally sought. It escalates from the student's request for help, the manner of which is deemed inappropriate by the teacher, through to what appears to be a protracted monologue by the student in the face of the teacher’s non-communication and student perceived inequity culminating in student removal from the class and most likely subsequent sanctions, thereby compounding his sense of alienation. The intensity of Dominic’s recounting suggests similar antecedent negative classroom experiences. Consequently, he expresses hopelessness about succeeding in classes with particular teachers whereas in other classes with other teachers he works very well and engages perfectly.

Anesthetised

Not all pedagogic communication is so volatile and out of control. In the case of some class groups in this study the type of interaction is withdrawn verbal engagement of any kind. Consultation with colleagues, in the case of one of the teachers in the research sample, revealed her frustration with one of the group’s poor engagement levels which was replicated in other classes: ‘and it’s across the board. I’ve asked other teachers who have them’ (Teacher Julia). Teacher David observes that classes are ‘very subdued, … they seem to be anesthetised, there is no energy in that class in particular [ 3rd years] … my 6th year class is similar to them, they are the most zoned out 6th year class I have ever had’. In other classes, some students typically present as having difficulty engaging, some daydream or temporarily disengage. In these classes the interaction rules are not challenged but rather taken to the other extreme where the rules are not used at all because they are not necessary, the class is ‘closed down’. The scale and level of the non-engagement complicate the nature of remedial action required to address the issue. Not only do they not engage in learning tasks, but they also remain unresponsive to the teacher's effort to assist them:

Teacher Julia: No one has ever asked me anything in class [in response to her offers of clarification] They leave things blank rather than ask … they shrug their shoulders, it’s because I forgot to do it or I didn’t want to do it, or I didn’t feel like it, sounds cheeky but it is just complete disengagement.

Classroom observation notes confirm the statements of teachers and students concerning patterns of passive non-engagement of students in a range of classes. Evidence of knowledge sharing between student and teacher or between student and student was a rare occurrence among this group.

‘Wrecking their heads’

Some more typical disruptive students in the sample deliberately adopt behaviours that challenge classroom codes. Publicly enacted ploys are routinely used by students to ‘wreck teachers’ heads’, and/or divert teacher-planned classroom activities. They tip what Willis refers to as ‘the axis of control’ and replace teacher order and orderliness with student disorder. They create noisy distractions that interfere with classroom communication, shouting, throwing classroom materials, challenging, confronting and provoking the teacher, raising the noise level beyond the tolerance of the teacher or what would allow teaching and learning to take place. They attempt to provoke the teacher’s reaction, ‘just to have a laugh’, mimicking teacher talk as a form of ridicule, verbally abusing the teacher or other students. These students reject/deny teacher authority. They ignore teachers’ instructions for order and engagement in-class tasks. They challenge teacher statements and strive to draw teachers into confrontational exchanges by repeatedly denying their misbehaviour or engaging the teacher in off-task conversation. Examples of incidents of this type of engagement include:

Not acknowledging teacher authority

Student Calvin: ‘ They’re not in charge of me … giving a teacher stick … tell a teacher to shut up … walking out of class … They told her to get out of my face and all, F— off away from me

Unauthorised talking which seems to be constant

Student June: They’d be talking all the time, everyone just talks non-stop … they are picking fights [arguments] just to stop the teacher from working … and the miss’d [would be] be asking them to stop and they’d say no, don’t tell me what to do … They shout a lot, they just talk whenever they want, they just make sure they can say what they want to say … whenever they feel like not doing any work they just say it to any teacher’ they shout across the classroom.

‘Slagging’ teachers:

Student Calvin: If they said something,’ just laugh at them I’d say what they had said back to them in a funnier voice, I dunno [don’t know], just wrecking their heads’ … . talking, throwing stuff at the teacher, slagging her’.

Ignoring teacher instruction:

Student Calvin: Not doing stuff that I am asked to do. Playing games on the computer, looking at pictures and all

Engaging in confrontational exchanges

Student Bella: … and I was messing and the teacher said stop!

And I say ‘I didn’t do anything’ (she mimics her voice in recalling this interaction) and the teacher says ‘I saw you’ and I say ‘no you didn’t’ and she says ‘you’re always doing it’ and then I would go mad.

What has been presented above are many different discursive strategies used by teachers and students to engage in some form of pedagogic communication to facilitate teaching and learning. The failure of all of these to engage the learners calls into question the efficacy of the approaches evidenced on the part of students and teachers. Nobody is gaining here; instead, the trajectory is compounding experiences of alienation and marginalisation. With few exceptions students display a strong desire to access the code of schooling, recognising its potential to provide them with a degree of control over their lives. However, for a variety of reasons, only a small number of students achieve this as many of the students gain only partial access as ‘active enquirers’ (Bernstein Citation2000) in their learning. Teachers too struggle to deal with the interactions and the code that frames these interactions. There is evidence in the study (not reported here) of some success on the part of some of the approaches used by teachers, but this is not significant enough to negate the types of experience described above.

Concluding comments

The students reported above all present different ways of engaging with school. For those who are overt and confrontational in their interactions, the classroom becomes a conflicted terrain as teachers and students ‘compete for scarce resources of communication space’ (Edwards and Furlong Citation1978, 23). To restore order, teachers impose a disciplinary ‘apparatus intended to render individuals docile and useful … [consequently] the asymmetries of disciplinary subjection’ (Foucault Citation1977, 231–232) render any notion of the community of learners and any resemblance of a Bakhtin-like dialogic enquiry impossible. The culture does not contribute to fostering a sense of belonging among students nor is there much evidence of engagement with school or learning. Irrespective of the complexity of its origin, the forms of discourse presented in the data produce ‘a state of perilous equilibrium’ (Waller Citation1932) with teachers and students engaged in a ‘battle of wills’ (Russell and Slater Citation2011, 73). Instruction becomes secondary and students are excluded, self-exclude and exclude others from the pedagogic process. Those students who are unresponsive in class – anesthetised – have retreated and hidden in silence (Delpit Citation2012) and do not seek anything from their teachers. This is evidenced, in the main, in the effort expended by teachers to support students to achieve success in school, by expressions of teacher frustration at the thwarting of this objective, and by the teacher’s professional tenacity to persevere through what they are experiencing as ‘exceptionally challenging’ circumstances. Despite their teaching methodologies being tested to the limit, and at times beyond the limits, the teacher’s concern for student welfare prevails. In all cases, irrespective of the teacher strategies deployed, the outcomes are not good and pedagogic communication is impoverished at best and absent most of the time.

The data present students who in the main want to learn and the overall study provides evidence of teachers who are strongly and tenaciously committed to supporting their students. This is not the first time that data of this kind have been reported and it is not that education systems have not been changing; indeed, there is a view that systems are always reforming but never changing very much in terms of which social groups benefit most. Many scholars have called for a radical transformation of education to avoid producing the type of outcomes reported here. Slee (Citation2011) and Slee and Thompson argues for more inclusive models of education and call for radical system reform. Others (Allan Citation2008; Fleming and Harford Citation2021; Graham Citation2020; Mac Ruairc Citation2013; Mac Ruairc Citation2020; Norwich and Koutsouris Citation2017) echo the need for a seminal shift at the system level, to interrupt current paradigms, to bring about more profound shifts in practice. Critical pedagogues, drawing on and developing the work of Freire (Citation1972, Citation1997), argue for emancipatory alternatives where conscientisation results in a critical awareness of context that can be mobilised for transformative reflection and action (Giroux Citation2019; Biesta Citation2017).

It might be that waiting for the big reveal of an alternative inclusive model of education is a way of avoiding more agentic reforms at a more local school level. Trying to make sense of the alienating culture that prevails is complex but the imperative to explore what is happening and seek ways to transform the context is unavoidable. Looking at this data from a Bernsteinian perspective there is compelling evidence that the regulative discourse of pedagogy device has fully dominated the instruction in this school to the extent that in most cases learning is either very limited or not happening at all. This instructional/regulative relational discourse is at the core of pedagogic communication and the pedagogic device. Because this pedagogic core is significantly off balance and because this is so important, it is very clear that this is where the action is needed. Putting high-quality, empowering and inclusive teaching at the core of the work of the school is essential. Evidence from within mainstream and alternative models of education that puts this ‘pedagogy first’ indicates the transformative potential of this type of re-calibration (Kovačič et al. Citation2021). The code that is generative of the norms that prevail in the school is creating a context where the only option available is to resist and create an alternative code and way of engaging with the school that is denying students all that education has to offer in its broadest sense. In many ways, it is the Willis lads all over again. It is also creating an intolerable career trajectory for teachers and this too is something that requires action. What we have here is closed, impoverished and ultimately creating student and teacher alienation where reproducing failure becomes an inevitable outcome.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ursula Nolan

Ursula Nolan worked as a second level teacher in schools in marginalised communities for all of her teaching career. She completed her PhD - How is class today? An examination of inclusion, participation and in a case study second level disadvantaged school. Ursula was awarded her PhD posthumously by UCD following her untimely death on June 10th 2017.

Gerry Mac Ruairc

Gerry Mac Ruairc is the Established Professor of Education and Head of School in the School of Education, NUI Galway and Senior Research Fellow with the UNESCO Child and Family Centre and the Institute for LifeCourse and Society NUI Galway. He has published widely in the areas of leadership for inclusive schooling, language and social class, literacy as well as in the areas of leadership and school improvement for equity and social justice.

References

- Allan, J. 2008. Rethinking Inclusive Education. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Bader, M. D. M., A. Lareau, and S. A. Evans. 2019. “Talk on the Playground: The Neighborhood Context of School Choice.” City & Community 18 (2): 483–508.

- Bakhtin, M. 1984. Problems of Dostoevsky’s poetics. Edited by C. Emerson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bernstein, B. 1971. Theoretical Studies Towards a Sociology of Language (Class, Codes and Control, Vol. 1). London: Routledge &Keegan Paul Ltd.

- Bernstein, B. 1973. Applied Studies Towards a Sociology of Language (Class Codes and Control, Vol. 2). London: Routledge & Keegan Paul Ltd.

- Bernstein, B. 1975/1977. Class, Codes and Control: Volume 3 – Towards a Theory of Educational Transmissions. 2nd ed. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Bernstein, B. 1990. The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse (Class, Codes and Control, Vol. 4). London: Routledge.

- Bernstein, B. 1996. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Bernstein, B. 1977. Class, Codes and Control. vol. 3. London: Routledge & Kegan Pau.

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique.

- Biesta, G. 2017. “Don’t be Fooled by Ignorant Schoolmasters: On the Role of the Teacher in Emancipatory Education.” Policy Futures in Education 15 (1): 52–73. doi:10.1177/1478210316681202.

- Creswell, J. W. 2003. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. London: SAGE Publications.

- Crompton, R. 2008. Class and Stratification. 3rd ed. London: Wiley.

- Delpit, L. 2012. “Multiplication is for White People” Raising Expectations for Other People’s Children. New York: The New Press.

- Derrida, J. 1987. Archeologie Du Frivole. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Edwards, A. D., and V. J. Furlong. 1978. The Language of Teaching. London: Heinemann Educational Books.

- ESRI. 2020. Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Policy in Relation to Children and Young People. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute. doi:10.26504/sustat94.

- Fairclough, N. 2001. Language and Power. 2nd ed. London: Longman.

- Fleming, B., and J. Harford. 2021. “The DEIS Programme as a Policy Aimed at Combating Educational Disadvantage: Fit for Purpose?” Irish Educational Studies. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1964568.

- Flynn, N., E. Keane, E. Davitt, V. McCauley, M. Heinz, and G. Mac Ruairc. 2021. “‘Schooling at Home’ in Ireland During COVID-19’: Parents’ and Students’ Perspectives on Overall Impact, Continuity of Interest, and Impact on Learning.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 217–226. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1916558.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

- Freire, P. 1972. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Penguin.

- Freire, P. 1997. Pedagogy of the Heart. London: Continuum.

- Giroux, H. A. 2019. “Neoliberalism and the Weaponising of Language and Education.” Race and Class 61 (1): 26–45.

- Goodenow, Carol, and Kathleen E. Grady. 1993. “The Relationship of School Belonging and Friends’ Values to Academic Motivation Among Urban Adolescent Students.” The Journal of Experimental Education 62 (1): 60–71. doi:10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831.

- Graham, L. 2020. Inclusive Education for the 21st Century: Theory, Policy and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography, Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. Devon: Routledge.

- Hasse, T., and J. Pratschke. 2014. “A Longitudinal Study of Area-Level Deprivation in Ireland, 1991–2011.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 41: 1–15.

- Korpershoek, H., E. T. Canrinus, M. Fokkens-Bruinsma, and H. de Boer. 2020. “The Relationships Between School Belonging and Students’ Motivational, Social-Emotional, Behavioural, and Academic Outcomes in Secondary Education: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Research Papers in Education 35 (6): 641–680. doi:10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116.

- Kovačič, T., C. Forkan, P. Dolan, and L. Rodriguez. 2021. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre. Galway: National University of Ireland.

- Kvale, S. 2007. Doing Interviews. London: Sage.

- Luke, A. 2018. Critical Literacy, Schooling, and Social Justice: The Selected Works of Allan Luke. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Lyotard, J. F. 1984. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mac Ruairc, G. 2009. “‘Dip, Dip, Sky Blue, Who's It? Not You’: Children's Experiences of Standardised Testing: A Socio-Cultural Analysis.” Irish Educational Studies 28 (1): 47–66. doi:10.1080/03323310802597325.

- Mac Ruairc, G. 2011a. “They’re My Words – I’ll Talk How I Like! Examining Social Class and Linguistic Practices Among Primary School Children.” Language in Society 25 (6): 535–559.

- Mac Ruairc, G. 2011b. “Where Words Collide: Social Class, Schools and Linguistic Discontinuity.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 32 (4): 541–561. doi:10.1080/01425692.2011.578437.

- Mac Ruairc, G. 2013. Including Inclusion - Exploring Inclusive Education for School Leadership. Dublin: Teaching Council of Ireland. Accessed July 14th 2022. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/research-croi-/research-webinars-/past-webinars/leadership-for-inclusive-schools-article.pdf

- Mac Ruairc, G. 2020. “That’s Enough About Me: Exploring Leaders’ Identities in Schools in Challenging Circumstances.” In Theorising Identity and Subjectivity in Educational Leadership Research, edited by R. Niesche, and A. Heffernan, Chap. 13. London: Routledge.

- Norwich, B., and G. Koutsouris. 2017. Addressing Dilemmas and Tensions in Inclusive Education. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Quantz, Richard. 1999. “School Ritual as Performance: A Reconstruction of Durkheim's and Turner's Uses of Ritual.” Educational Theory 49 (4, Fall): 493–513.

- Quantz, Richard. 2011. Rituals and Student Identity in Education: Ritual Critique for a New Pedagogy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Reay, D. 2006. “The Zombie Stalking English Schools: Social Class and Educational Inequity.” British Journal of Educational Studies 54 (3): 288–307.

- Reay, D., G. Crozier, and D. James. 2011. White Middle Class Identities and Urban Schooling. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Russell, B., and G. R. L. Slater. 2011. “Factors that Encourage Student Engagement: Insights from a Case Study of ‘First Time’ Students in a New Zealand University.” Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 8 (1): 81–96.

- Slee, R. 2011. The Irregular School. London: Routledge.

- UN. 2020. “Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and Beyond.” United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf.

- Waller, W. 1932. The Sociology of Teaching. New York: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1037/11443-000.

- Weir, S., and L. Kavanagh. 2018. The Evaluation of DEIS at Post-Primary, Weir and Lauren Kavanagh. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.