ABSTRACT

While student voice pedagogies have been cited as a powerful educational tool in engaging children in the learning process, the perspectives of primary-aged children on using these pedagogies as part of everyday practice need to be considered. Within this research, student voice pedagogies were implemented as part of one teacher’s regular primary physical education (PE) practice and children’s perspectives of these pedagogies were explored. Qualitative data were collected from two consecutive cohorts of children (n = 39) over a 6-month and 9-month period respectively. Data sources included the children’s written entries in their PE scrapbooks, along with transcripts from focus group interviews (n = 4, with 16 total participants) and a teacher-led classroom discussion (n = 1). Findings show that providing children with space to share their input, along with the appropriate information to inform their voices is important to the children. Offering choices and opportunities for the children to direct their learning experiences greatly mattered to how they experienced PE. These findings illustrate the value of student voice pedagogies as everyday practice to the quality of children’s experiences in physical education. The merits of listening to student perspectives on student voice to ensure these pedagogies add value is highlighted.

Introduction

Student voice is a ‘powerful lever’ for children’s involvement in decision-making (Charteris and Smardon Citation2019a, 93) and has a transformative impact on the engagement of students in the learning process. While student voice pedagogies offer a method by which students’ participation can be nurtured (Fielding Citation2004), guidance is lacking on how these pedagogies can be employed as part of regular classroom practice (Skerritt, Brown, and O’Hara Citation2023) particularly at primary level (Mayes, Finneran, and Black Citation2019). Furthermore, primary children’s perspectives of student voice practices are largely absent from the literature. Without a better understanding of how student voice pedagogies can be implemented, student voice risks being peripheral and having little to no impact on their learning experiences. In particular, it is crucial to understand how student voice is experienced by children and currently such evidence is lacking. The aims of this research are to explore primary children’s experience of student voice pedagogies in physical education (PE) and examine the role of these pedagogies in the enhancement of their PE experiences. This paper argues for the merits of and possibilities for the inclusion of student voice within a teacher’s everyday practice in the primary school classroom, using the children’s data as evidence.

Student voice in theory and policy

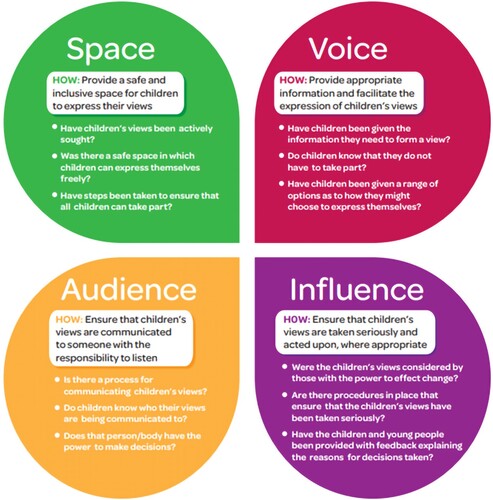

According to Dewey (Citation1938, 296), education is a democratic endeavour, where ‘every individual becomes educated only as [they have] an opportunity to contribute something from [their] own experience’. As a form of participatory democratic education (Sant Citation2019), student voice provides a method by which students are actively involved in educational decision-making (Mitra Citation2004) and viewed as co-creators of the curriculum, ‘raising their voices and having their views taken into account’ (Sant Citation2019, 673). The ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) provides a foundation for the inclusion of student voice practices in education, with many curricula and educational approaches having been inspired by Article 12, which states that a child’s view must be considered on all matters affecting them (Children’s Rights Alliance (CRA) Citation2010). To help organisations and people who work with children comply with Article 12, Lundy (Citation2007) developed a model for children’s participation in decision-making (see ). As can be seen in , the model proposes the need for four elements in decision-making processes: children should have the space to express their views, their voice should be enabled, their views must be communicated to an appropriate audience, and their voices must have an influence.

Figure 1: Lundy’s Model of Participation (Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA) Citation2015).

In Ireland, the publication of the National Strategy on Children and Young People’s participation in Decision Making, 2015–2020 (DCYA Citation2015), which was underpinned by Lundy’s (Citation2007) model of participation, placed a focus on student voice through children’s active participation in decisions affecting their lives. Further building on this national strategy, the recent publication of the Primary Curriculum Framework (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) Citation2023) supports the inclusion of children in decision-making specifically within the primary classroom, describing how children should be ‘active and demonstrate agency as the capacity to act independently and to make choices about and in their learning’ (NCCA Citation2023, 9). While Lundy’s (Citation2007) model provides some guidance on determining authentic decision-making opportunities, conflicting ideas exist within the literature regarding what student voice pedagogies should look like and ‘where or when the pursuit of democratic ideals should begin’ (Enright et al. Citation2017, 460).

Student voice in practice

As a set of pedagogies, student voice has been described as multifaceted and complex (Jones and Hall Citation2022) with educators and researchers differing in their approach to its implementation in practice. In its simplest form, student voice is often viewed as children having a say in their learning or being consulted on matters affecting them (Fielding and Bragg Citation2003). However, it has been argued that many pedagogies which involve children in decision-making are tokenistic in nature, offering children space to share their views, without offering their voices due influence (Lundy Citation2007). According to Cook-Sather (Citation2018, 17), student voice should encourage students to ‘speak and act … as critics and creators of educational practices’. Thus, it is important to differentiate between democratic pedagogies which offer children a degree of agency in their learning (i.e. closed choices), and those which allow them to have ‘a say in shaping what is taught, how it is taught, how their learning is assessed, and/or what classroom norms or routines look like’ (O’ Conner Citation2022, 14). Some student voice advocates have gone so far as to suggest that it should not only aim to improve student engagement and outcomes ‘within the existing frameworks of practice’ (Groundwater-Smith and Mockler Citation2019, 30), but rather the frameworks themselves should be the subject of critique. For example, Fielding and Moss (Citation2011, 75) propose a reconfiguring of the roles of students and teachers, describing a ‘radical democratic school’ in which ‘fluidity and exploration’ are encouraged amongst staff and students. In this vision, students and teachers are enabled to work together towards improvement (Hall Citation2020).

Within Irish schools, school self-evaluation policy represents the most significant and visible use of student voice pedagogies to date (Fleming Citation2015), in which the voices of students are enlisted to contribute to an overall aim of whole school improvement. In this sense, student voice is used ‘in the form of a learner lens for teachers’ fostering reflection and prompting teachers to take pedagogic action (Charteris and Thomas Citation2017, 167). However, student voice pedagogies that are implemented for the sole purpose of evaluating practice offer only an indirect benefit to students, missing the emancipatory potential of student voice and failing to fully realise the capabilities of the approach (Charteris and Smardon Citation2019b). Fleming (Citation2015) further noted that externally mandated policy initiatives involving student voice which focus solely on school improvement and performativity, lack any significant motivation towards student voice ‘as a person-centred dialogic interaction within an inclusive classroom and school culture’ (Fleming Citation2015, 238)

Student voice in Irish primary schools

While significant research has been conducted in the area of student voice in Irish post-primary schools (e.g. Fleming Citation2015; Skerritt et al. Citation2023), limited research and guidance exist at primary level. Children’s School Lives (CSL), a longitudinal cohort study of primary schooling in Ireland, recently published a report (Devine et al. Citation2023) providing insight into student voice pedagogies within Irish primary schools. Findings show that while most children felt listened to by their teacher, less than half of children stated that they were involved in decision-making in school, with interviews with children highlighting ‘an absence of their voice in what and how they learned’ particularly in the more senior primary classes (Devine et al. Citation2023, 32). Although teachers in the study recognised the value of the children’s voices, it was viewed as ‘an added extra to their pedagogy’ rather than embedded into day-to-day teaching and learning (Devine et al. Citation2023, 36). Furthermore, the report noted ambiguity around school policies in student voice, and teachers lacked specific professional development in the area. Similar findings were also reported by Forde et al. (Citation2018) and Turner, Ring, and O’Sullivan (Citation2020), who found that while Irish primary children had a say in some decisions, such as the books they read, games they played in PE, or in naming the class goldfish, the choices given to children were ‘relatively minor and peripheral’ and had ‘little impact on the core activities in which children participate in school’ (Forde et al. Citation2018, 498).

While the above-mentioned research provides an overview of what student voice practices already exist within the Irish education system, more guidance is needed on what student voice pedagogies can be used at primary level and how they can be implemented into the everyday practice of the classroom, within time, curricular and accountability pressures (Mayes, Black, and Finneran Citation2021).

Student voice in PE

Physical education (PE) is one subject area where the potential of student voice pedagogies is being harnessed in research and practice. For many years there have been moves to take PE away from traditional, teacher-oriented approaches towards those that more actively involve students in the entire learning process (e.g. Enright and O’Sullivan, Citation2010). Evidence from post-primary education shows that student voice practices can lead to more meaningful experiences in PE (Walseth, Engebretsen, and Elvebakk Citation2018), along with higher engagement amongst historically disengaged students such as girls (e.g. Enright and O’Sullivan Citation2010). Several specific strategies that promote student voice, such as the use of taster sessions, digital/written reflections, and cooperative learning (Howley Citation2022), have also been proposed to increase students’ agency and autonomy over their learning. Notably, data and guidance on student voice pedagogies in a primary PE context is lacking (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022a).

One pedagogical approach which is strongly aligned with the ethos of student voice is Meaningful Physical Education (Meaningful PE) (Fletcher et al. Citation2021). Meaningful PE proposes that by focusing on the provision of meaningful experiences for students in PE, students will be able to see the value and relevance of PE in their lives. Meaningful PE involves the consideration of features of participation that children themselves have identified as holding personal significance to them (such as fun, personal relevance, challenge, motor competence, and social interaction) (Beni, Fletcher and Ní Chróinín. Citation2017). Within a Meaningful PE approach, educators work closely with their students to ensure the presence of the above features within PE lessons, guided by the democratic and reflective pedagogical principles of the approach (Fletcher and Ní Chróinín Citation2022). Student voice pedagogies offer a means by which these democratic and reflective principles can be enacted, and guidance exists on how these pedagogies can be implemented within primary PE practice (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b). However, empirical evidence is lacking on both teachers’ and children’s experience of student voice pedagogies within primary PE practice. While research by Ní Chróinín et al. (2023) has provided evidence of children’s perspectives of democratic and reflective pedagogies in practice, the project was carried out over a limited timeframe and was lacking in offering insight into the sustained use of student voice pedagogies within democratic approaches. Thus, it is unclear how the prioritisation of democratic and reflective principles, using student voice pedagogies would play out over a longer period of time. With this in mind, the purpose of this paper is to describe the perspectives of children on student voice pedagogies used in primary PE practice over time.

Methodology

This research was part of a larger self-study of a teaching practice project that focused on the implementation of student voice pedagogies in a primary school classroom. Findings about Grace’s experiences of implementing this approach were reported in Cardiff et al. (in review). In the present paper, there is a shift away from the teacher’s perspective and towards the children’s perspectives. Thus, a different methodological approach is taken, representing a longitudinal ethnographic case study to capture children’s experiences of student voice pedagogies in a primary PE setting. Ethnography involves utilising a range of methods to ‘make sense of the world around us … by watching, experiencing, absorbing, living, breathing and inquiring about a culture, lifestyle event or even object’ (O’Reilly Citation2012, 1). This ethnographic research draws on a range of qualitative data sources to provide a rich description and interpretation of children’s experiences of student voice pedagogies.

Participants and setting

This research was carried out in a large, mixed-gender, rural DEISFootnote1 primary school in Ireland. Grace, who is a qualified primary school teacher and had five years teaching experience on commencing this project, was the primary investigator and classroom teacher in this project.

Children in Grace’s class were invited to be participants in this research. Student data were collected by Grace over a period of seventeen months, and involved two consecutive groups of 5th class students, who were aged 10–11 years old at the beginning of the study. Data was collected with the first group of students (n = 19) for a period of 6-months between January and June. For the second group of students (n = 20), data collection commenced in October and continued for the remaining 9 months in the academic year, concluding the following June. Students in this study had limited exposure to student voice practices in their previous years in education.

Ethical approval for this project was obtained from Mary Immaculate College Research Ethics Committee in Mary Immaculate College, Limerick (Ref: A21-039). Written consent was obtained from parents of the children before beginning the research, and the children indicated their assent. Non-consenting children continued to participate in PE lessons as normal and could not be identified by peers.

Overview of implementation

Guided by the democratic and reflective principles of the Meaningful PE approach (Fletcher and Ní Chróinín Citation2022), along with Lundy’s (Citation2007) model of participation, Grace implemented student voice pedagogies as part of her PE practice. To ensure the children were being afforded space, voice, audience, and influence in decision-making within their PE experience (Lundy, Citation2007), Grace employed a variety of student voice pedagogies during the weekly PE lesson, as shown in . It is important to note that this list does not constitute all ‘possible’ student voice pedagogies but rather those that Grace chose based on her experiences and priorities as a teacher and the children’s needs, interests, and preferences:

Table 1. Student voice pedagogies used.

Data sources

Several qualitative data sources were used in this project to capture children’s experiences of student voice pedagogies. As this research was framed within a larger self-study design, Grace could not separate herself from the data entirely. Grace’s post-lesson reflections, transcripts from critical friend meetings, along with critical friend responses to Grace’s reflections offered a teacher’s perspective on the implementation of student voice pedagogies, which has been discussed in another paper (Cardiff et al., in review). Although teacher data is not the focus of this paper, these data sources offered observations of the children’s experiences which often were not represented in the children’s written reflections.

Student data was collected in the form of PE scrapbooks (n = 39) with multiple entries (approx. 20) by each child. Children used the scrapbooks before and after PE lessons to offer their input and respond to reflection prompts. In addition, focus group interviews (n = 4, with 16 total participants) were carried out at two points during the project: at the end of Year 1 and at the end of Year 2. Focus group interviews were used to garner more information about the children’s experiences. To control for teacher-student power dynamics, the interviews were conducted by a research assistant (Year 1) and a teacher who was known to the children but not directly involved in the research (Year 2). Audio recordings of the focus group interviews were transcribed and anonymised by a research assistant, who was not known to the children, to further protect the identity of the children. An informal discussion which occurred during the school day between Grace and her students was also recorded and served as a data source.

Data analysis

A reflexive thematic analysis approach was taken to analysing the data in this project, guided by Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2021) six-phase approach: dataset familiarisation, data coding, initial theme generation, theme development and review, theme refining, defining and naming, and writing up. Reflexive thematic analysis was selected as a good fit to explore the children’s experience of student voice practices as thematic analysis goes beyond merely reporting what is in the data, and ‘involves telling an interpretative story about the data in relation to a research question’ (Clarke and Braun Citation2014, 6626).

Dataset familiarisation was a continuous process throughout the project, as Grace was the classroom teacher and was interacting with the data regularly during the school year (i.e. by reading students’ scrapbooks often, and writing and rereading personal reflections). On beginning formal data analysis, Grace read and reread all data sources (i.e. personal reflections, critical friend meeting transcripts, focus group transcripts, and students’ scrapbooks entries). Grace then began to systematically review each data source and allocate codes to points which related to the research question. Themes were then generated in consultation with co-authors; the codes were reviewed and revised and grouped to form initial themes. Following this, the initial themes were further developed and refined. Provisional themes were reviewed in relation to both the children’s and teacher’s data. Finally, the findings were drafted in consultation with co-authors.

Trustworthiness of the analysis was addressed through the triangulation of multiple, rich data sources and through working with several authors in the data analysis process. The children were also invited to member check and offer feedback on a presentation which lined up with the findings of this paper, further ensuring trustworthiness of the data.

Findings

The findings of this research give insight into primary children’s experience of the use of student voice within a teacher’s everyday practice in primary PE. Findings are presented and will be discussed under three themes: My voice counts, I can use my voice to make choices that matter to me, and Taking control and getting to be in charge. Each theme is illustrated using direct quotes from the children.

My voice counts

Supporting children in developing their capacity to share their voice, and providing a safe learning environment to do so, was a necessary precursor to authentic student voice pedagogies (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b). The need to create a safe space in which children can share their voices, along with providing the appropriate information to inform children’s voices is central to Lundy’s (Citation2007) model of participation. In this research, priority was given to supporting children in expressing their voices throughout PE lessons using democratic and reflective pedagogies (Fletcher and Ní Chróinín Citation2022). Below, we provide evidence that the inclusion of their voices during PE lessons mattered greatly to the children and offered a means by which to develop their capacity to engage in democratic practices.

Sharing curriculum objectives at the beginning of PE lessons enabled children to see the purpose of the plan of activities (Ní Chróinín et al. 2023) and encouraged them to be active participants in the learning process (Glasson Citation2009). The children noted how in previous years learning objectives or a lesson outline were not shared with them, noting how ‘the teacher would just plan it’ (FG1, A). In discussion with Grace, most children stated that they liked when the lesson objectives and outline were shared as it provided them with an idea of what was to come, while also offering an opportunity for student input. One child noted how this practice ‘helps us have a say in things, which is really nice’ (VW). Sharing information about the lesson was pivotal in affording the children an initial opportunity to have their voices heard, while serving to equip them with the knowledge needed to make informed decisions during the lesson (Lundy Citation2007; Lundy Citation2018). As one child stated: ‘It helps us know what we’re going to do so we can better prepare in between activities in PE’ (VW).

Reflective practices employed during lessons, which involved small- and whole-group discussions, also proved to be essential in providing the children with space and giving influence to the children’s voices (Lundy Citation2007). Many children responded positively to these mid-lesson reflections:

I think it really helped because [in previous years] you might be playing a game but you really don’t like it and you might just be thinking I have my hand up the whole time and the teacher just keeps doing the game and when am I going to tell her that I don’t like this game. (ST)

Reflective pedagogies employed post-lesson, such as whole class discussions, exit-tickets and written reflections in the children’s PE scrapbooks, served to further facilitate the children in the expression of their voices. One child noted how post-lessons reflections afforded them influence over future learning experiences, as the teacher would ask ‘what worked well, what didn’t work well, and then for the next week we could change it so it would be better.’ (FG2, R). The children appreciated having the opportunity to share their thoughts about different aspects of the lesson, along with contributing ideas for future lessons:

If a game didn't work, you'd be able to talk to Ms. Cardiff about it and then in the next PE lesson, she'd say that, a lot of people didn't really think this game worked. So we wouldn't do it again, or we try and make it better with our own ideas, we try and … put some of our own ideas in it. And then we'll see how that game goes again. (FG2, D)

Reflective pedagogies supported the children’s investment in the planning process (Ní Chróinín et al. 2023) and complemented pedagogies which afforded them greater freedom to direct their own learning (i.e. the pedagogy of choice).

I can use my voice to make choices that matter to me

Iannucci and Parker (Citation2022b) proposed that there is a need for progressive scaffolding of opportunities for children to have a say and input in their learning, but empirical evidence of primary children’s experiences is lacking. This theme illustrates how a pedagogy of choice can be used to support children in considering their learning needs, while facilitating movement towards a more collaborative approach to decision-making in PE, providing both an audience and influence to students’ voices (Lundy Citation2007).

Throughout PE lessons, the children were supported in making choices regarding the content and delivery of the lesson. Although these choices were often modest (for example choosing a warm-up activity) they allowed the children to assert more influence on decision-making in the lesson (Lundy Citation2007) and make decisions ‘about issues of immediate relevance to their own lives in PE’ (Howley and O’Sullivan Citation2021, 13). The children were empowered to alter the level of challenge of activities by selecting an option which best matched their ability, a feature which has been identified as frequently leading to meaningful experiences in PE (Beni et al. Citation2017). Choice regarding the level of challenge was viewed as an important aspect of the PE lesson by the children; it fostered inclusivity (Ní Chróinín et al. 2023) and contributed to their overall engagement in and enjoyment of the lesson. As noted by one child:

Whenever we do PE, there’s always a couple of people out there just not trying as hard. And I think it’s because they think it’s too hard. And they don’t want to be seen to not be able to do it. So I think like a broader range of challenge [is needed], so that people who can do it, that can do it well, they can really challenge themselves but the people who can’t do it, they can really start from the basics and just really work their way up. (FG2, R)

If [the teacher] didn’t let you choose challenge and it was very hard for you, some people might give up … and then if it was no challenge at all you’d just say this is way too easy and you’d keep going over and over again. (FG2, D)

However, mirroring findings from Koekoek and Knoppers (Citation2015), while the children often preferred to work with friends, they also realised that their friends could become a distraction to learning. In a post lesson reflection, one child noted how they hated ‘working with others because my friends [are] always messing’ (AB). Others noted how self-selecting groups can often mean people ‘feel left out when everyone goes to their friends’ (Q) or how it was ‘a bit awkward to pick the group’ (TU). Furthermore, children recognised the value of working with new people in lessons, and often appreciated the groups which the teacher picked: ‘we got to work with friends and new people that we usually would not (best of both)’ (S). Providing the children with space and enabling their voices in choosing between self-selected groups and teacher-selected groups in lessons mattered greatly to the children (Lundy Citation2007), and reportedly influenced their enjoyment and learning within lessons.

By allowing the children choice around how they participated in activities, it created ‘potential spaces for empowerment and student involvement in the curriculum-making process’ (Howley and O’Sullivan Citation2021, 13). Children not only appreciated having a say in choosing their ‘just-right’ level of challenge and in the group selection, but they recognised the important roles that these choices played in shaping their PE experience, echoing findings within the Meaningful PE literature (e.g. Beni et al. Citation2017; Ní Chróinín et al. 2023).

Taking control and getting to be in charge

Opportunities for autonomy and agency can be provided by inviting students to contribute to the planning and delivery of PE lessons (Enright and O’Sullivan, Citation2010), and has been shown to help promote meaningfulness for students within PE at post-primary level (Walseth et al. Citation2018). In this research, Grace used self-created games and ‘personal practice time’ to enable children to take responsibility for their own learning in a way that benefitted them.

Self-designed games enabled the children to develop their agency (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b) and further direct their learning. Children were tasked in small groups to create a game, while considering the needs of themselves and others, that reflected the curricular focus of the day. As noted by Grace, the children took this responsibility seriously:

The students were really excited about [creating games], and the majority of them were wholly engaged in the planning activity, so much so that I had to remind them on multiple occasions to eat their lunch as they talked, as they were using up some of their lunch time to plan! (Reflection 22)

‘Personal practice time’ was offered in lessons to further foster children’s voices and afford them control over their learning. A 5–10-minute practice period during/at the end of the PE lesson allowed the children to continue to develop any skill or fundamental movement from the lesson. Mirroring the findings of Ní Chróinín et al. (2023), providing students with discretionary time to direct their own activities helped children to make connections between PE and their lives outside of school, allowing them to see the personal relevance of these activities to their lives, an element which has been noted as contributing to meaningful experiences within the Meaningful PE literature (Beni et al. Citation2017). Several children reported that personal practice time was the best part of the lesson, with some petitioning for ‘more time for us to do our own thing’ (MN). Children cited how they used this time to further develop skills of their choosing, and adapt the lesson to match their preferences, with one child stating: ‘it really helps me by working on stuff that I need to work on’ (CD). Several children noted how this time allowed them to make advances in their motor competence, an element which has been noted as leading to meaningful experiences in PE (Beni et al. Citation2017):

I couldn’t get over the hurdles the first day we tried to do them and then when I kind of just, every time we had the personal time at the end I kept on practicing and then by the final day I was able to do the 3 hurdles (RS)

Discussion

Having the opportunity to share their voices and direct their learning experiences in PE mattered to the children. Creating space for their participation and informing their voices, along with providing the appropriate audience and influence to their input (Lundy Citation2007) served to empower the children as learners, giving them greater agency over their learning experiences (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b). Grace’s position as both the primary investigator and the classroom teacher in this research allowed the student voice pedagogies employed to be matched to the changing needs and preferences of the children in real time. Furthermore, as the children became more invested in the decision-making process within PE, Grace was in the position to embed the use of student voice pedagogies in other curricular areas, in response to the children’s calls for greater autonomy throughout the school day.

Sharing their voices was important to the children. The use of democratic and reflective pedagogies (Fletcher and Ní Chróinín Citation2022), such as the sharing of lesson objectives and mid-/post-lesson reflective tasks, afforded the children space to share their input before, during and after PE lessons (Lundy Citation2007), while also prompting them to develop a deeper understanding of their experiences (Standal Citation2015). It has been argued that providing space alone, without affording the associated influence results in tokenistic practices and can lead to ‘disaffection and disillusionment and ultimately disengagement’ (Lundy Citation2018, 340-341). However, we propose that offering children space and opportunities to share their voices is an essential version of student voice practice which warrants additional consideration in the Irish primary classroom, particularly when students lack prior experience of the approach within their schooling (Skerritt et al. Citation2023). In line with Article 12 of the UNCRC, emphasis is often placed on giving influence to children’s voices (Lundy Citation2007), with the importance of Article 13 largely overlooked. Lundy (Citation2018) attests that even in cases when children’s voices cannot be given due weight, they can still enjoy the right to ‘seek, receive and impart information’ (CRA Citation2010, 15), and measures should be taken ‘to respect, protect and fulfil’ this right (Lundy Citation2018, 344). Thus, we argue that creating space for children’s voices serves an essential role in everyday classroom practice.

In line with findings from Ní Chróinín et al. (2023), the provision of unstructured play opportunities or ‘personal practice time’ allowed children to see the relevance of activities and make connections between PE lessons and their wider lives. In addition, the use of self-created games offered children an opportunity to develop their agency by identifying what they wanted to learn in the lesson (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b). This version of student voice reflected a step towards more collective and democratic decision-making (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b), closely aligning with the principles of participatory democratic education. However, as suggested in the findings, additional power/control was not always desired by the children, and some were reluctant to assume an active role in their learning at times. As noted by Welty and Lundy (Citation2013), children should be given the choice to participate in decision-making or not, rather than being obliged to contribute to every decision. The findings indicate the need to consider the capabilities and preferences of the children when enacting different versions of student voice. The implementation of student voice practices thus requires the considered and thoughtful involvement of the teacher, who plays an essential role in both facilitating and interpreting their students’ voices (Pearce and Wood Citation2019).

The pedagogy of choice also fulfilled a necessary function within lessons, by serving as a scaffold in developing the children’s confidence and competence in decision-making in PE (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b). The findings demonstrate the value children placed on opportunities for choice, while illustrating how these choices enabled them to develop their agency to shape their learning experiences (Ní Chróinín et al. 2023). Within the literature, choice is often positioned as a ‘stepping stone’ towards more authentic student voice practices (Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b). However, as we argued in Cardiff et al. (in review), we question the prevailing tendency to categorise student voice along a figurative ladder (e.g. Hart Citation1992), the act of which implies that the more responsibility given to students, the more beneficial the approach is overall (Jones and Hall Citation2022). The pedagogy of choice provided Grace with a practical and feasible way of introducing student voice into her practice, in a way in which both she and the children were comfortable with. Although we believe that children would benefit from additional freedom and involvement in decision-making practices, as suggested in the literature, this stretched beyond the capacity of Grace as a classroom teacher who was bounded by the curriculum and had limited experience of student voice practices (Cardiff et al., in review). Thus, we suggest that student voice research, which offers ‘the ideals of student voice practice’ (Jones and Hall Citation2022, 575) should be viewed as ‘guiding lights’ and a starting point for dialogue, rather than a goal or aim for educators in everyday practice.

Within this research, the experiences of children in one school context were explored, providing some direction for educators’ seeking to implement student voice pedagogies within their own practice. Although Lundy’s (Citation2007) model of participation offers guidance on the elements which should be present in student voice practices (i.e. space, voice, audience, and influence), additional research involving students and educators in a variety of contexts would add richness and nuances to the understanding of how student voice pedagogies operate in primary schools. Furthermore, while PE was the starting point for this research, initiating similar investigations in other subject areas, in line with the principles of the Primary Curriculum Framework (2023), might provide alternative narratives and/or practical direction to educators in enacting student voice pedagogies across the curriculum.

Conclusion

This paper provides an important perspective of student voice pedagogies in classroom practice, by describing the experiences of the children themselves. The findings illustrate how sharing their voices matters to children, and how involving them in a more democratic and reflective approach to learning in PE serves to empower them in shaping their learning experiences to match their preferences (Fletcher and Ní Chróinín Citation2022; Ní Chróinín et al. 2023). The paper adds to existing literature in primary PE (i.e. Iannucci and Parker Citation2022b) by offering empirical data on the implementation of student voice, and illustrates the potential of student voice practices in nurturing personally significant learning experiences. The children’s attitudes towards student voice pedagogies remained consistent, with advice offered by the children at the end of the research all portraying a similar sentiment: ‘Let children have a say’ (PQ).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Grace Cardiff

Grace Cardiff is a qualified primary school teacher in Ireland. She is undertaking her PhD journey at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick, and her work focuses on the use of student voice pedagogies in fostering more meaningful experiences within primary physical education practice.

Déirdre Ní Chróinín

Déirdre Ní Chróinín is the head of department and senior lecturer in Arts Education and Physical Education at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick, Ireland. Her research interests are in teaching, learning and assessment in primary/elementary physical education; initial teacher education in physical education; meaningful experiences in physical education, physical activity and sport; leadership in school physical education; qualitative research methodologies including visual methods and self-study research methodologies.

Richard Bowles

Richard Bowles is a lecturer in the Department of Arts Education and Physical Education at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick. He teaches physical education in undergraduate and postgraduate primary/elementary teacher education programs. He also volunteers as a coach with some of the College’s Gaelic Football teams. Richard’s research interests included school and community sport, teacher and coach education, and self-study research methodologies.

Tim Fletcher

Tim Fletcher is an associate professor at Brock University in Ontario, Canada. Prior to teaching in universities Tim taught high school health and physical education for five years. His current research focuses on how teachers implement pedagogies that support meaningful experiences for learners in physical education, highlighted in a recent co-edited text Meaningful Physical Education: An Approach to Guide Teaching and Learning (2021, Routledge) with Déirdre Ní Chróinín, Doug Gleddie and Stephanie Beni. He is also interested in various forms of practitioner research, particularly using self-study methodology.

Stephanie Beni

Stephanie Beni is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Teacher Education and Outdoor Studies at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences in Oslo, Norway. Her research interests lie primarily in understanding the ways young people experience meaningfulness in physical education and identifying practical tools by which physical education teachers can foster meaningful experiences for students. In addition, she enjoys studying her own practice and the process of supporting teachers in their professional learning.

Notes

1 DEIS (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) is an action plan for educational inclusion launched by the Department of Education and Skills in 2005. The plan focuses on addressing the educational needs of children in disadvantaged areas through additional support and funding to schools.

References

- Beni, Stephanie, Tim Fletcher, and Déirdre Ní Chróinín 2017. “Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education and Youth Sport: A Review of the Literature.” Quest 69 (3): 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Charteris, J., and D. Smardon. 2019a. “Democratic Contribution or Information for Reform? Prevailing and Emerging Discourses of Student Voice.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 44 (6): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v44n6.1.

- Charteris, Jennifer, and Dianne Smardon. 2019b. “The Politics of Student Voice: Unravelling the Multiple Discourses Articulated in Schools.” Cambridge Journal of Education 49 (1): 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2018.1444144.

- Charteris, Jennifer, and Eryn Thomas. 2017. “Uncovering ‘Unwelcome Truths’ Through Student Voice: Teacher Inquiry Into Agency and Student Assessment Literacy.” Teaching Education 28 (2): 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1229291.

- Child’s Rights Alliance (CRA). 2010. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Dublin: CRA.

- Clarke, V., and V. Braun. 2014. “Thematic Analysis.” In Encyclopaedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, edited by A. C. Michalos, 6626–6628. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Cook-Sather, Alison. 2018. “Tracing the Evolution of Student Voice in Educational Research.” In Radical Collegiality Through Student Voice: Educational Experience, Policy and Practice, edited by Roseanna Bourke and Judith Loveridge, 17–38. Singapore: Springer Publishers.

- Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA). 2015. National Strategy on the Participation of Children and Young People in Decision-Making, 2015–2020. Dublin: DCYA.

- Devine, D., G. Martinez-Sainz, J. Symonds, S. Sloan, B. Moore, M. Crean, N. Barrow, et al. 2023. Primary Pedagogies: Children and Teachers’ Experience of Pedagogical Practices in Primary School in Ireland 2019-2022. Report No. 5. UCD School of Education. https://cslstudy.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/CSL_Report5_ForPublication.pdf.

- Dewey, John. 1938. “The Determination of Ultimate Values or Aims Through Antecedent or a Priori Speculation or Through Pragmatic or Empirical Inquiry.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 39 (10): 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146813803901038.

- Enright, Eimear, Leanne Coll, Deirdre Ní Chróinín, and Mary Fitzpatrick. 2017. “Student Voice as Risky Praxis: Democratising Physical Education Teacher Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 22 (5): 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2016.1225031.

- Enright, Eimear, and Mary O'Sullivan. 2010. “‘Can I do it in my Pyjamas?’ Negotiating a Physical Education Curriculum with Teenage Girls.” European Physical Education Review 16 (3): 203–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X10382967.

- Fielding, Michael. 2004. “Transformative Approaches to Student Voice: Theoretical Underpinnings, Recalcitrant Realities.” British Educational Research Journal 30 (2): 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000195236.

- Fielding, Michael, and Sara Bragg. 2003. Students as Researchers: Making a Difference. London: Pearson.

- Fielding, Michael, and Peter Moss. 2011. Radical Education and the Common School: A Democratic Alternative. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fleming, Domnall. 2015. “Student Voice: An Emerging Discourse in Irish Education Policy.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 8 (2): 223–242.

- Fletcher, Tim, and Déirdre Ní Chróinín. 2022. “Pedagogical Principles That Support the Prioritisation of Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education: Conceptual and Practical Considerations.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 27 (5): 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1884672.

- Fletcher, Tim, Déirdre Ní Chróinín, Douglas Gleddie, and Stephanie Beni. 2021. “The why, What, and how of Meaningful Physical Education.” In Meaningful Physical Education, edited by Tim Fletcher, Déirdre Ní Chróinín, Douglas Gleddie, and Stephanie Beni, 3–19. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Forde, Catherine, Deirdre Horgan, Shirley Martin, and Aisling Parkes. 2018. “Learning from Children’s Voice in Schools: Experiences from Ireland.” Journal of Educational Change 19 (4): 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-018-9331-6.

- Glasson, Toni. 2009. Improving Student Achievement: A Practical Guide to Assessment for Learning. Wolverhampton: Curriculum Press.

- Groundwater-Smith, Susan, and Nicole Mockler. 2019. “Student Voice Work as an Educative Practice.” In Participatory Methodologies to Elevate Children’s Voice and Agency, edited by Ilene R. Berson, Michael J. Berson, and Colette Gray, 25–46. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

- Hall, Valerie J. 2020. “Reclaiming Student Voice(s): Constituted Through Process or Embedded in Practice?” Cambridge Journal of Education 50 (1): 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1652247.

- Hart, Roger A. 1992. Children's Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship. Florence: United Nations Children’s Fund International Child Development Centre.

- Howley, Donal. 2022. “Talking the Talk, Walking the Walk: Six Simple Strategies for Enacting Student Voice in Physical Education.” Strategies 35 (6): 38–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2022.2120350.

- Howley, Donal, and Mary O’Sullivan. 2021. “‘Getting Better bit by Bit’: Exploring Learners’ Enactments of Student Voice in Physical Education.” Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education 12 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2020.1865825.

- Iannucci, Cassandra, and Melissa Parker. 2022a. “Beyond Lip Service: Making Student Voice a (Meaningful) Reality in Elementary Physical Education.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 93 (8): 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2022.2108177.

- Iannucci, Cassandra, and Melissa Parker. 2022b. “Student Voice in Primary Physical Education: A 30-Year Scoping Review of Literature.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 41 (3): 466–491. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2021-0007.

- Jones, Mari-Ana, and Valerie Hall. 2022. “Redefining Student Voice: Applying the Lens of Critical Pragmatism.” Oxford Review of Education 48 (5): 570–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2021.2003190.

- Koekoek, Jeroen, and Annelies Knoppers. 2015. “The Role of Perceptions of Friendships and Peers in Learning Skills in Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 20 (3): 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2013.837432.

- Koekoek, Jeroen, Annelies Knoppers, and Harry Stegeman. 2009. “How do Children Think They Learn Skills in Physical Education?” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 28 (3): 310–332. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.28.3.310.

- Lundy, Laura. 2007. “‘Voice’ is not Enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.” British Educational Research Journal 33 (6): 927–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033.

- Lundy, Laura. 2018. “In Defence of Tokenism? Implementing Children’s Right to Participate in Collective Decision-Making.” Childhood 25 (3): 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568218777292.

- Mayes, Eve, Rosalyn Black, and Rachel Finneran. 2021. “The Possibilities and Problematics of Student Voice for Teacher Professional Learning: Lessons from an Evaluation Study.” Cambridge Journal of Education 51 (2): 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2020.1806988.

- Mayes, Eve, Rachel Finneran, and Rosalyn Black. 2019. “The Challenges of Student Voice in Primary Schools: Students ‘Having a Voice’ and ‘Speaking For’ Others.” Australian Journal of Education 63 (2): 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944119859445.

- Mitra, Dana L. 2004. “The Significance of Students: Can Increasing “Student Voice” in Schools Lead to Gains in Youth Development?” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 106 (4): 651–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810410600402.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 2023. Primary Curriculum Framework. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

- Ní Chróinín, Déirdre, Tim Fletcher, Stephanie Beni, Ciara Griffin, and Maura Coulter. 2023. “Children’s Experiences of Pedagogies That Prioritise Meaningfulness in Primary Physical Education in Ireland.” Education 3-13 51 (1): 41–54.

- O’ Conner, Jerusha. 2022. “Educators’ Experiences with Student Voice: How Teachers Understand, Solicit, and use Student Voice in Their Classrooms.” Teachers and Teaching 28 (1): 12–25.

- O'Reilly, Karen. 2012. Ethnographic Methods. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pearce, Thomas C, and Bronwyn E Wood. 2019. “Education for Transformation: An Evaluative Framework to Guide Student Voice Work in Schools.” Critical Studies in Education 60 (1): 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1219959.

- Sant, Edda. 2019. “Democratic Education: A Theoretical Review (2006–2017).” Review of Educational Research 89 (5): 655–696. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319862493.

- Skerritt, Craig, Martin Brown, and Joe O’Hara. 2023. “Student Voice and Classroom Practice: How Students are Consulted in Contexts Without Traditions of Student Voice.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 31 (5): 955–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1979086.

- Standal, Oyvind. 2015. Phenomenology and Pedagogy in Physical Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Turner, Sorcha, Emer Ring, and Lisha O’Sullivan. 2020. “The Transformative Power of Child Voice for Learning and Teaching in Our Classrooms: Signposts for Practice from Research Findings in a Primary School in Ireland.” LEARN The Journal of the Irish Learning Support Association 41: 7–17.

- Walseth, Kristin, Berit Engebretsen, and Lisbeth Elvebakk. 2018. “Meaningful Experiences in PE for all Students: An Activist Research Approach.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (3): 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1429590.

- Welty, Elizabeth, and Laura Lundy. 2013. “A Children’s Rights-Based Approach to Involving Children in Decision Making.” Journal of Science Communication 12 (3): C02.