ABSTRACT

School networks have become increasingly prevalent in education in recent decades, particularly with a focus on improving student outcomes in contexts of socio-economic disadvantage. To address the lacunae of literature and research nationally, this article presents findings from original case study research on two networks of disadvantaged schools in Ireland. Data was collected from interviews, focus groups, surveys with network members and documentary analysis. Drawing on international literature on school networks, social capital, social theory, and teacher professional learning (TPL) and findings from the research, this article explores how networking can support the development of individual members’ bonding social capital through peer interaction and development of their professional capital to enhance capacity to respond to complexity. Additionally, it outlines how fostering bridging and linking social capital can support schools in disadvantaged contexts to collectively respond to intractable social issues by connecting network members’ priorities to those of key stakeholders and building lateral capacity. As such, these networks can be viewed as a divergent approach to TPL that also supports schools to develop networked agency to respond to complexity and change in Irish society.

Introduction

Globally, society has become increasingly complex with a myriad of pervasive challenges including societal inequity, income poverty, health inequality, the climate crisis, migration, unemployment, the technological divide, and the recent pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war, all of which have serious implications for the field of education and educational leaders (Brown and Flood Citation2020; Fullan Citation2019; Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016; Schleicer Citation2016; Stevenson Citation2023; Stoll Citation2010). These challenges have permeated schools and classrooms nationally, with their impact undoubtedly felt most keenly in disadvantaged schools, which in Ireland are supported by the Delivering Equality of Opportunity in School (DEIS)Footnote1 School Support Programme. DEIS schools have greater concentrations of students at far greater risk than others of not achieving their potential in education (Fleming and Harford Citation2023; Frawley Citation2014; Harford et al. Citation2022; Smyth and McCoy Citation2009), including those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, Traveller backgrounds, non-English speaking backgrounds and with Special Education Needs (Smyth, McCoy, and Kingston Citation2015). This is evident in the persistent nature of ‘educational disadvantage’ in terms of socio-economic, class and ethnic differentials in educational outcomes for students (Delaney et al. Citation2023; Drudy and Lynch Citation1993; McNamara et al. Citation2021; Smyth Citation2018a; Citation2018b; Smyth and McCoy Citation2009; Smyth, McCoy, and Kingston Citation2015), disparities in outcomes between those attending DEIS and non DEIS schools (Delaney et al. Citation2023; DoE Citation2017; Gilleece et al. Citation2020; Neils and Gileece Citation2023) and consistent under-representation of students from ‘disadvantaged’ backgrounds in higher education (Clancy Citation2001; HEA Citation2015; Citation2018; HEA Citation2022; McCoy et al. Citation2010; McCoy and Byrne Citation2011; O'Connell, Clancy, and McCoy Citation2006; Scanlan et al. Citation2019). The demographics of DEIS schools have significant implications for school staff in terms of responding to the evolving, complex social context of inequality.

This article presents findings from an original piece of research on two networks of DEIS schools, the first of its kind nationally on this topic, which sought to understand members’ perspectives on how networking has supported both individual members and schools over a twenty-year period. The networks were established in recognition that disadvantaged schools need multifaceted support to respond to complex issues arising from inequality, particularly in the absence of a whole government response to social exclusion that recognises the endemic nature of and intersectionality of multiple dimensions of inequality (Cahill Citation2015; Fleming and Harford Citation2023; Jeffers and Lillis Citation2021).

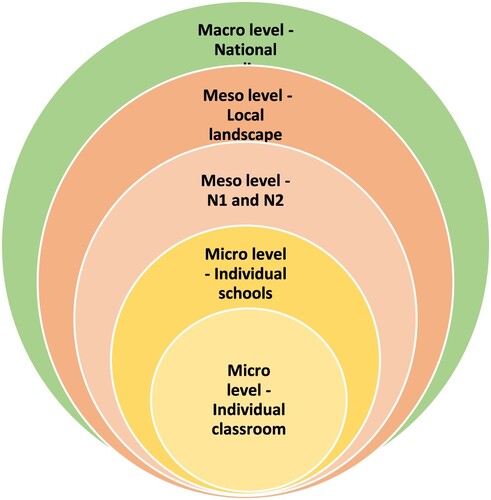

A key contribution is the insight on how networking can support schools in disadvantaged contexts within centralised education systems to respond to complexity by enhancing social and professional capital and creating connections from the micro, to meso and macro level thereby building lateral capacity (Fullan Citation2019) and strengthening the ‘middle’ tier (OECD Citation2015). In centralised education systems, such as that in Ireland, where there are no local or regional education departments, the middle tier is comprised of clusters of schools (Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016, 19).

The conceptual framework drew on social theory, social capital (SC) theory, and literature on school networks and teacher professional learning (TPL) to problematise the contribution and limitations of these particular networks.

Conceptual framework

Inequality and social reproduction in education

Inequality in education is multi-faceted, complex, related to ingrained social, economic and educational issues and endemic (Doyle and Keane Citation2019; Drudy and Lynch Citation1993; Frawley Citation2014; Kellaghan Citation2001; Scanlan Citation2020). The diverse range of factors at family, school, neighbourhood and societal level that underpin unequal outcomes in education are well documented (Doyle and Keane Citation2019; Drudy and Lynch Citation1993; Frawley Citation2014; Kellaghan Citation2001; Lynch and Baker Citation2005; McAvinue Citation2022; O’ Sullivan Citation2005; Smyth Citation2018b).

Economic, social and cultural capital play a significant role in the social reproduction of inequality and perpetuation of class and other differentials in education through the ideology of meritocracy (Bourdieu Citation1997; Kellaghan Citation2001; Lareau Citation2015; O’ Sullivan Citation2005). Through habitus, a form of socialisation, the cultural capital of dominant groups is unconsciously transmitted and reproduced by middle class institutions, such as schools (Bourdieu Citation1979; Citation1997) and students from ‘subordinate’ groups become alienated due to the discontinuity between the worlds of home and school (Kellaghan Citation2001; Lareau Citation2015). The subsequent educational success of dominant groups is misrecognised and legitimised through ‘symbolic violence’ as the natural order or due to their individual giftedness (Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1979, 22), competence, and merit rather than due to class-based differentials (Mills Citation2008).

Recognition of the role of economic and cultural capital in perpetuating inequality reveals just how difficult it is for students and parents in DEIS schools to compete on a level playing field. Courtois (Citation2015; Citation2018) and Kennedy and Power (Citation2010) illuminate the role of economic and cultural capital in the reproduction of privilege in elite Irish private schools. Their greater economic capital allows the middle and upper middle classes to pay for and reap the benefits of factors known to be positively related to student outcomes, i.e. privileged learning conditions, better facilities, higher expectations, smaller class size, access to private tuition and access to educational resources (Lynch and Lodge Citation2002; Kennedy and Power Citation2010; Courtois Citation2018). While fee-paying schools are also funded by the Irish government, non-fee-paying schools must supplement their income with voluntary contributions from parents. This has significant implications for DEIS schools. McNamara et al.’s research (Citation2021) indicates that DEIS primary schools were responsive to family capacity to pay voluntary contributions, with 59% of those in DEIS Band 1Footnote2 primary schools not asked for a contribution, compared to only 30% in non-DEIS schools. Overall, those with higher income levels were more likely to be asked to pay higher contributions (ibid). The ability of DEIS schools to offer the aforementioned optimal learning conditions and resources and infrastructure to provide diverse extracurricular opportunities (McCoy Citation2021) that can advance academic performance, which are important in the context of socio-economic gaps in achievement (McCoy, Smyth, and Banks Citation2012), are thus greatly diminished. The policy of voluntary contributions is ‘deeply inequitable’ (Lynch and Crean Citation2018, 7) due to differences in parents’ economic resources. Furthermore, in the neoliberal market-based education system in Ireland, it legitimates and perpetuates social class stratification through education as more privileged groups use education to ‘ensure optimum benefit for their children’ (Lynch and Lodge Citation2002, 40).

Some gains have been made in DEIS schools in recent years in literacy and numeracy at primary level (Smyth, McCoy, and Kingston Citation2015; Kavanagh, Weir and Moran Citation2017), improved retention at Junior and Senior cycle (Smyth, McCoy, and Kingston Citation2015; Kavanagh, Weir and Moran Citation2017) and more recently in reading, maths and science at post-primary level (Gilleece et al. Citation2020). However, recent research indicates that the gap between DEIS and non-DEIS schools has not narrowed significantly (Delaney et al. Citation2023; Neils and Gileece Citation2023). These findings raise questions about the adequacy of the resourcing of the DEIS programme to bridge the gap between DEIS and non DEIS schools (Fleming and Harford Citation2023; Smyth, McCoy, and Kingston Citation2015) and more significantly, about the capacity of isolated and ‘piecemeal’ (Jeffers and Lillis Citation2021, 2) initiatives from one government department to reduce deep-seated inequality and tackle complex societal issues (Cahill Citation2015; Cahill and O’Sullivan Citation2022; Educational Disadvantage Committee Citation2005; Fleming and Harford Citation2023; Fleming, Harford, and Hyland Citation2022; Jeffers and Lillis Citation2021; McAvinue Citation2022).

School networks supporting schools to respond to complexity

Networking and collaboration are increasingly prevalent in education internationally. Harris, Azorín, and Jones (Citation2021, 1) observed a ‘seismic shift in networking activity between and across education systems’ since COVID. Networks have emerged to promote improvement in student outcomes, knowledge exchange, collaboration, professional learning and innovation, and more equitable education systems (Azorín Citation2020; Azorín, Harris, and Jones Citation2020; Brown and Flood Citation2019; Chapman Citation2019; Díaz-Gibson et al. Citation2017; Fullan Citation2019; Muijs et al. Citation2011; Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016). Key findings and policy recommendations from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) indicate that teacher professional development and collaboration are important factors in terms of student achievement and outcomes, particularly in schools with higher proportions of socio-economically disadvantaged students (OECD Citation2017; Citation2019). In a context of increased international competitiveness and pervasive societal challenges, Stoll (Citation2010) asserts that networking and collaboration have developed as many issues are far too complex for individual schools to tackle alone and a more ‘divergent’ (472) approach to professional learning is required (Brown and Flood Citation2020; Díaz-Gibson et al. Citation2017; Stoll Citation2010). Networks of schools in ‘challenging circumstances’ involving other stakeholders have developed in response to a wide variety of measures to improve outcomes for children (Azorín Citation2020; Herrera-Pastor, Juárez, and Ruiz-Román Citation2020; Rincón-Gallardo Citation2020; Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016).

Collaborating with other schools experiencing similar challenges provides opportunities for joint problem solving, a key aspect of the following definition of school networks adopted in this research:

A network … is a group of organisations working together to solve problems or issues of mutual concern that are too large for any one organisation to handle on its own (Mandell Citation1999). Applied to school, the idea of networks suggests that schools working together in a collaborative effort would be more effective in enhancing organisational capacity and improving student learning than individual schools working on their own (Wohlstetter et al. Citation2003, cited in Chapman and Hadfield Citation2010a, 310).

The establishment of networking initiatives has been shown to support schools in effecting improvement (DoE Citation2017, 30).

The significance of networks for DEIS schools, as this research has found, lies in their capacity to support the development of different types of SC, i.e. bonding, bridging (Putnam Citation2000) and linking (Grootaert et al. Citation2004). Subsequently, they foster members’ professional capital (Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012) through a process of peer interaction which enhances TPL relevant to the social context of DEIS schools, supports their capacity to respond to complexity arising from inequality and creates opportunities to advocate for resources and support.

Social capital and the development of professional capital

Social capital theory illuminates how the process of networking creates opportunities for the development of individual and collective SC through interaction with those in similar roles and the advantages that accrue from same at both the individual and collective level. SC is conceptualised as resources residing in social networks and investment in embedded resources or assets in social networks with expected returns (Bourdieu Citation1997; Coleman Citation1997; Field Citation2003; Li Citation2015; Lin Citation1999). Bridging SC can bring people together across diverse social divisions, while bonding SC reinforces exclusive identities, maintains homogeneity and can foster solidarity and group loyalty (Field Citation2003; Putnam Citation2000). These are of particular salience for this research which views the main effects of SC as the information, influence and solidarity which accrue to members of a ‘collectivity’ (bonding SC) and to individuals and collectives in their relations to other actors (bridging SC) (Kwon and Adler Citation2014, 412). Linking SC (Grootaert et al. Citation2004, 4) was also significant and is vertical in nature, i.e. the ties that individuals have to those in positions of authority connecting people across ‘power differentials’ to key political and other resources and economic institutions.

Collaborative practices and interactions amongst teachers and schools (e.g. school networks, Professional Learning Communities or Networks and Communities of Practice) help to build SC through opportunities for exchange of resources or assets in the form of information, advice and support, access to expertise, dissemination, negotiation, adoption and adaptation of pedagogical knowledge and instructional materials (Bridwell-Mitchell and Cooc Citation2016; Coburn and Russell Citation2008; Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012; Johnson, Lustick, and Kim Citation2011; Stoll Citation2010).

At the collective level, the advantages that accrue from SC include trusting relationships that enable collective action and the pursuit of shared goals and support collaborative professional learning (Sleegers, Moolenaar, and Daly Citation2019). These relationships are built through the structure of the networks, which distinguish them from other organisational forms (Church et al. Citation2002; Kerr et al. Citation2003; Chapman and Hadfield Citation2010a) and enables bringing people together to organise connections between them (Chapman and Hadfield Citation2010a). These can be hard i.e., membership, coordination, formal and informal structures, and soft i.e., trust, relationships and knowledge. Linking SC can connect schools and learning communities to the wider educational landscape including district, regional and national bodies, training bodies or Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) (Mulford Citation2010; Stoll Citation2010), essentially creating links between the macro level of individual experience to meso and macro levels (Field Citation2003). The advantages of collective school networking lie in the increased flow of information (Muijs et al. Citation2011, 21) and the greater influence or ‘collective pressure’ (Jones and Harris Citation2014, 476) that can be exerted on the social and political landscape than when individuals act in isolation (Jones and Harris Citation2014; Lin Citation1999; Muijs et al. Citation2011).

Developing teachers SC through peer interaction highlights how school networks can be an important vehicle to support staff in DEIS schools to respond to complexity through a process of peer learning that ultimately builds both their human and social capital. As Hargreaves and Fullan (Citation2012, 102) observe:

It’s not enough for teachers of the disadvantaged [sic] and the poor to have a heart of gold. They need to have a treasure chest of knowledge and expertise too. They need to know how to make brilliant connections between the capital children need to get upward access and the existing cultures of these children’s families and their communities. To do this well, teachers need considerable human and social capital of their own.

Materials and methods

This research aimed to conduct a thorough analysis of how these two networks evolved, how they function, in what way they contribute to knowledge creation and sharing and to gain insight about how DEIS schools can be supported through the process of networking.

A qualitative exploratory, instrumental case study (Stake Citation1995) was adopted. Network members comprised the unit of analysis, i.e. those who represent their school on the networks and have experience of same. Network One (N1) was set up in 1998 and includes 14 DEIS Band 1 school and two special schools. Home School Community Liaison Coordinators (HSCLs)Footnote3 primarily represent their school on the network but there are some class teachers. Network Two (N2) was established in 2009 and membership includes principals from 12 DEIS Band 1 and 4 DEIS post -primary schools. Both networks are facilitated by aHEI, with a statutory agency involved in facilitating N2 from 2009 to 2019. Ethical clearance was granted by Mary Immaculate College Research Ethics Committee (MIREC).

Primary data () was gathered through focus groups, in-depth individual interviews and surveys with network members. There is an overlap of 12 primary schools between the networks. During the data collection period, every representative was invited to participate in a focus group, followed by an interview and a subsequent survey. Facilitators of N2 also participated in a focus group and individual interviews. The researcher facilitated N1 for much of the time during the data collection phase.

Table 1. Primary sources of data.

Secondary data analysed () involved documentary analysis of agendas and minutes of meetings from 1999 to 2018. Multiple methods and sources of data generation facilitated triangulation of sources of evidence (Creswell Citation2014; Merriam Citation1998; Robson Citation2011; Stake Citation1995; Yin Citation2009).

Table 2. Secondary sources of data.

Two case study reports were written outlining the model of each network based on the research findings and key elements of school networks identified in the literature, i.e. purpose, structures, processes and interactions (management and leadership, participation, learning and interpersonal relationships and trust) and challenges (Azorín and Muijs Citation2017; Chapman and Hadfield Citation2010a; Citation2010b; Church et al. Citation2002; Hadfield and Chapman Citation2009; Hopkins Citation2003; Katz et al. Citation2008; Kerr et al. Citation2003; Lieberman Citation1999; Lieberman and Grolnick Citation2005; Lima Citation2010; McLaughlin, Black-Hawkins, and McIntyre Citation2004; Muijs et al. Citation2011; Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016).

Data analysis

Qualitative data was analysed through a six-step process (Creswell Citation2014, 197–201). First and second cycle coding were adopted (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2014, 86–87) to thematically analyse data using QSR NVivo 11 software. Meeting agendas, minutes and associated documents were analysed through one cycle of coding as the documents were incorporated specifically for contextual and historical information and to triangulate participants’ accounts. Survey results were analysed using SPSS and incorporated into the write up of the draft findings. Findings presented here are primarily drawn from interview and focus groups data and outline and discuss the role that the networks play in building social capital at the individual and collective level. Research participants were assigned a random numberFootnote4 to anonymise for direct quotation, along with N1 or N2 to identify the network to which they belong.

Findings – how social capital is built in the networks

Bonding social capital, trust, relationships and networked agency

Bonding SC was instrumental in developing trusting relationships between members of each network at the outset. Initial relationships were founded on the shared sense of understanding of the DEIS school context and over time evolved into solidarity, collegiality, camaraderie, peer support and ‘friendships’ or more personal relationships. In N2, this helped to break down barriers between schools, the HEI and statutory agency at the beginning and ease reservations that some research participants held about the motives of the statutory agency at the outset. For HSCLs, N1 is a valuable ‘networking’ opportunity to meet others in the same role for peer support in the absence of formal supervision in their role. N2 was described as a support group for DEIS principals ‘in the front line’ with participants emphasising the ‘isolation’ experienced in their leadership role and how peer support from principals in schools with ‘similar issues and similar problems’ (N2-35) helped to combat the same.

The networks provide members with opportunities for both ‘quality and quantity’ (Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012, 90) interaction and discussion in a ‘friendly’, ‘open’, ‘relaxed’, and ‘positive’ atmosphere which incorporates both formal e.g. agenda, timekeeping and informal aspects e.g. tea/coffee, chatting, freedom to bring something to the discussion. These interactions impact on access to information and knowledge (ibid) and the networks have become a platform for the ‘exchange of resources’ (Adler and Kwon Citation2002; Coburn and Russell Citation2008) with others ‘in the same boat’ (N1-79 & N2-64) in the form of information sharing, advice, feedback, ideas, best practice, problem solving, guidance, reassurance and support. This extends to communication between members outside of meetings.

Facilitative and supportive structures (Mulford Citation2010, 198) foster trusting relationships, i.e. what research participants described as ‘good facilitation’, ‘listening’, ‘respect’, confidentiality, creation of a ‘safe space’, being non-judgemental, the role of the neutral or ‘objective’ facilitator in N2 and follow through on issues of concern. In turn, trust allows for greater social exchange and cooperation (Nahapiet and Ghoshal Citation1998) as well as exchange of more valuable or sensitive information (Leana and Pil Citation2006). The significance of trust was more prominent in N2 participant’s accounts, likely due to members’ leadership role and the challenges they deal with arising from the complex social issues and inequalities that non-DEIS counterparts in other professional organisations or support groups do not understand. Competition between schools in N2 for enrolments was acknowledged, but as trust built, people ‘came out of their silos’ (N2-64) to work towards a common goal. N2 participants also revealed that they feel they can vent, let rip and be honest about ‘what the reality is on the ground’ (N2-51) within their ‘safe space’, which indicates their willingness to ‘be vulnerable’ based on their confidence in the good intentions of other members (Misztral Citation1996) and a reduced sense of uncertainty about other members based on prior interaction (Sleegers, Moolenaar, and Daly Citation2019).

Bonding SC also enhances cohesion, cooperation and collaboration in the networks. Over time, cohesion buttressed by bonding SC, reciprocal relationships and trust, has facilitated the networks to collaborate towards common goals (Sleegers, Moolenaar, and Daly Citation2019) and developed ‘networked agency’ (Hadfield and Chapman Citation2009, 6). Collectively, the networks have advocated on many issues affecting DEIS schools over a twenty-year period and secured resources to deliver initiatives to directly support schools to respond to their concerns including the promotion of positive behaviour in school, developing family, school, community relationships and changing demographics and cultural and linguistic diversity. Over time bonding SC reinforced members sense of cohesion and purpose of ‘making a difference in children’s lives’ (N2-44) to respond to changing needs of members and the environment (Kools and Stoll Citation2016).

Bonding social capital supports the development of professional capital

Bonding SC has played a significant role in professional learning (Kools and Stoll Citation2016) and development of professional capital (Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012) in both networks. As observed above, relationships between network members provide opportunities for interaction and exchange of resources in the form of information, advice, feedback, ideas, best practice, problem solving, guidance, reassurance and support (Kools and Stoll Citation2016; Lima Citation2010; Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016). Such interactions not only increase members’ prospects of tapping into the human capital (knowledge and skills) and intellectual capital (knowledge and knowing capability) (Leana and Pil Citation2006; Nahapiet and Ghoshal Citation1998) of others, it also enhances their ‘decisional capital’ (Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012) or capacity to make professional judgements grounded in practice, experience and reflection.

Accessing the knowledge and experience of colleagues was cited in the N1 case study report as helping members to learn about different initiatives and supports that their school or students’ families can avail of, to solve problems or concerns, to seek feedback or suggestions on particular issues, and to learn about what is working for others so that ‘you can bring that back to the table in your school’ (N1-81). Sharing practice and experience with colleagues in this way can ‘set off some lightbulbs in your head’ (N1-78) about how things might be applied in their own school. N1 participants emphasised the relevance of this type of learning for teachers who don’t often get the opportunity to meet others outside their class, never mind their school, and for HSCLs who don’t often get the chance to network with each other. N2 participants detailed how bonding SC had contributed to their professional capital in the form of advice on different issues from other members, sharing of information about funding or supports for schools, problem solving, bouncing ideas off colleagues, access to ‘little pockets of knowledge’ (N2-51) that they can tap into and insights or ‘nuggets’ from other principals. Due to the insular nature of the leadership role and the level of responsibility they hold, as well as the context of being a leader in a DEIS school, this type of insight and experience from colleagues was perceived as very beneficial particularly as principals are often expected to ‘have the answer to every issue’ (N2-36) in their own school. N2 participants indicated that learning through sharing of experience with others in similar contexts was an important way to develop their leadership style by drawing on the experience of others, i.e. ‘what worked, what didn’t work and what they did’ (N2-56), as they navigate the role of principal. It helped them ‘to know what to expect’ with experiences they have never dealt with before, i.e. a DEIS inspection. It also inspired ‘confidence’ in others to try things out in their school, ‘they tried that, I might give it a shot’ (N2-51).

The enhancement of professional capital in the networks through the sharing of insights and experiences and bonding SC, is similar to learning in Communities of Practice (CoPs) through ‘thinking together’ (Pyrko, Dörfler, and Eden Citation2017; Citation2019) and the articulation and exploration of tacit knowledge through dialogic ‘learning conversations’ (Stoll Citation2010, 475), whereby such knowledge is explored and assumptions are challenged. This type of exchange of resources creates an environment that supports professional learning (Coburn and Russell Citation2008; Johnson, Lustick, and Kim Citation2011) and is explored in further detail elsewhere (Bourke Citation2022) in relation how these networks also operate as CoPs.

Bridging and linking social capital, access to information, expertise and information flows

In addition to relationships built between members via bonding SC, N1 and N2 promoted the development of connections and relationships with other stakeholders through bridging (Field Citation2003; Putnam Citation2000) and linking SC (Grootaert et al. Citation2004). Not only does this strengthen connections in the ‘middle’ tier (OECD Citation2015), the impact for individual members and their schools has included access to support and resources, the creation of information flows and feedback loops, advocacy on behalf of children and families in DEIS schools and contribution to the wider educational landscape in the city where the networks are based and connection between the micro, meso and macro level.

Bridging SC is fostered in the networks by creating connections with other stakeholders such as staff in educational organisations and statutory and community agencies with a remit to support children and families. This supports information flows (Lin Citation1999) and ‘double-loop learning’ (Kools and Stoll Citation2016, 21) between members and staff in other stakeholder organisations. N1 was cited as providing opportunity for new HSCLs in particular to ‘build relationships’ (N1-13) with support agencies that are vital to their role. N2 participants emphasised links made with ‘big players’ locally including statutory and education support agencies. Such ‘multiagency’ links were perceived as beneficial because they improved communication with other stakeholders, provided an opportunity for schools to raise ‘our concerns’ (N2-55), raised awareness amongst members about ‘what’s going on in the wider world’ (N2-35) and support and funding available. Essentially, the networks act as boundary spanners (Burt Citation1992) bridging structural holes or disconnections in people’s social ties, i.e. between network representatives/their schools and other stakeholders, helping to access important information for schools and avoiding the ‘echo chamber’ (Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016).

Both networks have been a platform for members to access the expertise of guest speakers and external stakeholders from the wider community including lecturers in education, staff from statutory agencies and community and voluntary agencies. These were described as ‘meaningful and helpful and relevant for our schools at that time’ (N2-51), ‘hugely beneficial’ (N1-79) and raising awareness of member’s about services, best practice, and when to refer someone to an agency. Additionally, they were described as essential to access ‘professionals and experienced people’ (N1-30) to support schools, children and families in the context of increasing demand for social supports in areas such as wellbeing and mental health, addiction, imprisonment, bereavement and homelessness. In this sense, creating connections with external stakeholders enhances members’ decisional and professional capital (Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012). Connections created with external stakeholders are also an important source of information about the resources and supports which HSCLs in N1 bring back to their schools and local clusters, with HSCLs acting as boundary spanners (Burt Citation1992) bridging information gaps between their different social networks and as brokers to new knowledge (Brown and Flood Citation2020), gained via N1, in their school or cluster. Ultimately, bridging SC as developed in the networks, fosters connections that support DEIS schools to implement their DEIS plan targets in relation to ‘partnership with others’ and to enhance whole school wellbeing as set out in Wellbeing Framework (Government of Ireland Citation2019).

Advocacy on behalf of DEIS schools, the wider educational landscape and connection between the micro, meso and macro

Bonding SC helped to create networked agency for collective action within the networks and foster a ‘united voice’. Bridging SC created between the schools and external stakeholders working towards similar goals provided N2 the opportunity to raise concerns directly with staff from statutory agencies which participants felt helped to raise awareness and access resources to support children. Having a statutory agency directly involved in N2 was viewed as providing verification or ‘weight’ within other sections of that agency that schools’ concerns about a particular ‘EALFootnote5 crisis’, or influx of migrants in a short period of time and the need for resources to respond to same, were ‘very real’ (N2-55). SC built in N2 provided kudos or ‘social credentials’ (Lin Citation1999) to access much needed resources. In the past, N1 also advocated on the highly contentious issue of middle-class post-primary schools ‘cherry picking’ students from more affluent backgrounds and middle-class primary schools.

N2 in particular was perceived as ‘feeding into national policy’ (N2-55) and described as a ‘united’ and collective voice for schools involved. Bridging SC creates ‘systemic extension’ (Stoll Citation2010, 472) to collectively leverage support from ties between the networks and the broader group of stakeholders (Adler and Kwon Citation2002), therefore, they can exert greater influence on the social and political landscape than if members acted in isolation (Jones and Harris Citation2014; Lin Citation1999; Muijs et al. Citation2011). Participants in N2 highlighted connections created with those in positions of authority, i.e. those ‘higher up the food chain’ (N2-35), to raise the concerns of the DEIS schools involved within political institutions, e.g. the Department of Education and Department of Children and Youth Affairs, exercising linking SC (Grootaert et al. Citation2004).

Bridging and linking SC not only connect the networks to the wider educational landscape they also serve to illuminate the connections between the micro, meso and macro levels of policy (Chapman and Aspin Citation2003; Hopkins Citation2003), as depicted in . The networks created a platform for staff from DEIS schools to bring practices, concerns or queries from individual classrooms and schools (micro level), to the networks (meso level) where interaction between members, i.e. school representative, HEI and statutory agency and school to school interaction occurs. This platform also facilitates interaction with other stakeholders in the local landscape that are involved in supporting children and families from DEIS schools, i.e. statutory agencies, community and voluntary groups, as well as those involved in teacher education/professional development. The concerns that filtered through from the micro level of the classrooms and schools, to the meso level of the school networks, are raised with a variety of local stakeholders and where relevant, raised at the national macro level via statutory agencies or on occasion, with the appropriate Minister. This process also supports the assertion that networks hold potential to create change by ‘leading from the middle’ (Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016).

Discussion

This research sought to understand how these two networks support DEIS schools and the findings reveal that bonding SC plays a crucial role in creating connections between members, founded on trust, that enhances members’ professional capital, and fosters cohesion, solidarity and networked agency to advocate on behalf of their schools. Through bridging and linking SC, connections are fostered with other stakeholders that create potential for concerns to permeate from the micro level of classrooms in DEIS schools to the macro level of the national policy landscape.

The findings about how these networks build SC can be directly correlated to their purpose and their categorisation as teacher professional learning and support networks (Azorín Citation2020) as opposed to those specifically focused on teaching, learning, improved student outcomes and effective pedagogy. While they broadly support teaching and learning activity, ascertaining the impact at the level of classroom or the individual student would be extremely complex and questionable in terms of value. However, the findings add to the existing international literature on school networks by delineating how the processes and interactions involved build ‘hidden’ or informal relationships, trust or internal accountability (Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016) and commitment to a common goal and the potential, as evidenced in N2, to connect the priorities of the micro level of DEIS schools, to the meso and macro layers of education in the centralised Irish education system by building lateral capacity (Fullan Citation2019) and strengthening the middle tier (OECD Citation2015). In contrast to much of the literature on school networks, teacher social networks and Professional Learning Networks, which adopt a ‘static’ structural perspective (Lima Citation2010) to understand the diffusion of teacher’s instructional and pedagogical practice, this research illuminates the relational and cognitive dimensions of social capital in school networks.

In doing so, it accentuates the agency of network members and the capacity of school networks for TPL relevant to members’ roles and to respond to complexity in disadvantaged schools, based on peer interaction and trust. Empirical research that highlights the processes and interactions of school networks is imperative (Azorín and Muijs Citation2017; Lima Citation2010), particularly for delineating how trust is built, as well as the limits of same in a competitive educational landscape (Lima Citation2010). Unfortunately, the findings do not reveal the parameters of trust, although it is evident that greater importance was placed on same by principals in N2.

There is some evidence that through the building of the three forms of SC, N2 created alignment between various layers of the system for systemic change (Stoll Citation2010) in the local environment, for example, through the involvement of a statutory agency in a local school network and the development of particular initiatives to maximise the use of schools for the wider community and subsequently, for network schools to respond to cultural and linguistic diversity and promote the school as a site to foster integration in the local community. Research on these particular interventions (Higgins et al. Citation2021; Oscailt Citation2013) indicates that they have contributed positively to the lives and learning of students, parents and school staff by: offering accessible opportunities to learn, develop skills and socialise, enhancing relationships between home and school, developing positive attitudes towards school, developing relationships between children, developing relationships between parents/adults, and in the case of the latter initiative, nurturing a sense of belonging and promoting integration in schools. Similarly, research on interventions delivered through N1 in response to members’ concerns about promoting positive behaviour in schools and developing family, school, community relationships, provides a more detailed analysis of the impact for children, parents, teachers and schools (Galvin, Higgins, and Mahony Citation2009; Higgins et al. Citation2021; Oscailt Citation2013). This confirms that building SC through school networks can support DEIS schools to deal with uncertainty and complexity in their environment (Muijs et al. Citation2011; Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016) and that networks can become more than the sum of their parts by developing into something new (Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016). Additionally, the findings illustrate how N2 members became ‘system players’ (Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016, p. 18) and exhibit ‘systemness’ as they moved from individualism to collaboration and thinking in terms of all the children across their schools as opposed to just in ‘my school’.

Building lateral capacity (Fullan Citation2019) through the development of SC in these networks also creates a greater repertoire of choices for DEIS schools by circulating practice around the system. These findings add to the literature to provide a deeper understanding of how the three forms of SC can be fostered through networking to support disadvantaged schools. The cognitive and social resources harnessed form the basis for building relationships between members and with external organisations that lead to TPL, accessing resources and expertise and advocacy for DEIS schools. While much of the research on DEIS schools details the many challenges faced, and class based and other differentials between DEIS and non DEIS schools, this research highlights how the collective agency of DEIS schools can be harnessed through networking and how staff in DEIS schools can challenge the ‘doxas of their own educational trade’ (Lynch Citation2019, 530) by giving them a platform and a voice in a centralised system where teachers and school leaders have very limited access to policy makers to raise awareness of the implications of inequality on the ground in their schools and advocate for policy change and greater resourcing to respond to same. However, the capacity of two networks of DEIS schools alone to challenge endemic societal and economic inequity is severely limited.

Limitations of this research

There are limitations to these networks related to the ‘dark side’ of SC (Adler and Kwon Citation2002; Baron, Field, and Schuller Citation2000; Brown and Lauder Citation2000; Field Citation2003; Kwon and Adler Citation2014). Restricting membership to a particular role, i.e. DEIS principal, HSCL or class teacher, excludes the voices and perspectives of those who do not participate, i.e. children, parents and other school staff, prevents them from benefitting from the various advantages of SC arising from the networks, leads to a greater degree of homogeneity in network membership and can create power imbalances. The lack of the teaching principal and post-primary principal voice in the research is a further limitation.

Methodologically, generalisation is a shortcoming of case study research (Punch Citation2009; Robson Citation2011; Stake Citation1995; Yin Citation2009). Given that networking is an emerging area of practice and the dearth of research on networking and collaboration between DEIS schools nationally, insights from ‘naturalistic generalization’ (Stake Citation1995, 8) and ‘analytic generalization’ (Yin Citation2009, 15) are highly relevant. The researcher’s direct involvement in N1 amplified the risk of researcher bias. Steps to minimise same included: establishing construct validity (Yin Citation2009) through triangulation of sources of evidence, establishing a chain of events and respondent validation (Bassey Citation1999; Creswell Citation2014; Merriam Citation1998); data gathering over a longer period of time to increase validity of findings (Creswell Citation2014; Merriam Citation1998) and clarification of researcher bias, assumptions and theoretical orientation (Bassey Citation1999; Creswell Citation2014; Merriam Citation1998).

Implications and recommendations

A number of key implications and recommendations arise from this research for practice and research. Participants emphasised the importance of a dedicated and skilled facilitator to execute the ‘coordination process’ (Azorín Citation2020, 114) involved in school networks and to ensure sustainability. This is important because of the demanding nature of members’ roles but also because the ‘deliberate leadership’ (Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016, 15) required to lead ‘effective’ networks involves capacity to deliver on varied and complex tasks such as building relationships and trust, brokering between different stakeholders, facilitating ‘dialogic’ discussion and learning in a ‘safe space’ and developing commitment to a ‘communally negotiated agenda’ (Wenger Citation1998, 78). The role of an ‘independent’ or neutral stakeholder in fulfilling this function is critical to building trust, particularly when school leaders are involved (Hadfield and Chapman Citation2009; Rincón-Gallardo and Fullan Citation2016).

The literature suggests that voluntary participation in school networks is preferable (Chapman and Hadfield Citation2010a), particularly in networks supported by educational policy to create systemic change, otherwise they run the risk of ‘contrived collegiality’ (Hargreaves Citation1994; Hargreaves and Fullan Citation2012). The involvement of a statutory agency in N2 was cited as a major incentive by participants for their own participation. Internationally, policymakers and other education stakeholders, such as HEIs are partners in school networks in many contexts. Given that the Irish education system is centralised, statutory agency and other educational stakeholder involvement with networks of DEIS schools holds significant potential for a more ‘joined up’ approach to tackle inequality in education as envisaged by the Educational Disadvantage Committee almost twenty years ago.

The gaze of international research has turned to examine leadership in networks and the relationship between leadership and professional collaboration (Azorín, Harris, and Jones Citation2020; Harris, Azorín, and Jones Citation2021; Rincón-Gallardo Citation2020). This is an area that should be examined in further research on school networks in Ireland, particularly the type of leadership that can create wider cultural and systemic change in education.

Conclusion

In the Irish context, this is an original piece of research that has problematised two unique networks theoretically, practically and from a policy perspective rather than taking an instrumental and normative view (Lima Citation2010). It demonstrates how bridging and linking SC have created links in the centralised Irish education system between the micro level of what’s happening ‘on the ground’ in DEIS schools, to the meso level, and macro level of educational policy thereby by raising awareness of key issues for DEIS schools locally and nationally. Because educational disadvantage is primarily viewed in isolation (Cahill Citation2015) and as a school-based issue in Irish educational policy (Fleming and Harford Citation2023), rather than a broader societal concern, DEIS schools desperately need support to raise awareness about the impact of social and economic inequity in their schools and the multidimensional and multidisciplinary interventions required to support children and families. Despite the ‘positive discrimination’ (Weir et al. Citation2017) of the DEIS School Support Programme, Irish educational policy continues to favour more affluent and privileged children through the ideology of meritocracy (Drudy and Lynch Citation1993; Kennedy and Power Citation2010; Lynch Citation2019; Lynch and Crean Citation2018) thus maintaining the status quo (Cahill and O’Sullivan Citation2022; Fleming, Harford, and Hyland Citation2022). In short, DEIS schools cannot, nor should they have to, work alone to address the challenges of inequality in education. While not a panacea, the appeal of school networks lies in their capacity to leverage resources and knowledge to improve outcomes for students (Rincón-Gallardo Citation2020). This is achieved by building social capital and harnessing the power of relationships within networks and connections between schools and other stakeholders.

School networking is an emerging area of practice in Irish education policy. The importance of having this evidence base to draw from is directly related to the exponential growth of networking and collaboration internationally over the last twenty years, which has become widespread as a policy for educational change and reform, far more quickly than the evidence about their effectiveness has been developed (Azorín Citation2020; Azorín and Muijs Citation2017; Azorín, Harris, and Jones Citation2020; Brown and Flood Citation2020; Harris, Jones, and Huffman Citation2018; Rincón-Gallardo Citation2020) and as Hargreaves and O’ Connor observe, not all forms of collaboration are equal or desirable. Despite the limitations identified, these two networks have been effective to some degree at supporting the DEIS schools involved to respond to complexity arising from social and economic inequity and raising awareness of same at the macro level.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the members of N1 and N2 who participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ruth Bourke

Ruth Bourke is an Assistant Professor and Coordinator, Transforming Education through Dialogue (TED) Project. She has been facilitating networks of schools for nearly twenty years and has led evaluations on initiatives in DEIS schools.

Notes

1 Delivering Equality of Opportunity in School (DEIS) is the Action Plan for Educational Inclusion, which was launched in May 2005 and remains the Department of Education policy instrument to address educational disadvantage. The second Action Plan was introduced in September 2017. Under the DEIS School Support Programme, approximately 1,200 schools, representing 240,000 students, receive additional resources and supports on the basis of the socio-economic profile of the community and school level data.

2 Schools are categorised at primary level as DEIS urban Band 1, Band 2 or rural based on the levels of disadvantage, with urban band 1 schools allocated the most resources. However, at post-primary level, there is no such distinction with all schools being categorised as DEIS post-primary.

3 The HSCL Coordinator is a teacher in a DEIS school who provides support through Home Visits, Parent classes/courses (recreational and educational), Transition Programmes and offers information on other family supports available locally. In addition, HSCL Coordinators can encourage and support parents in attaining their own educational goals.

4 https://www.randomizer.org/ A range of 10 – 100 was specified for a set of 35 potential interview participants.

5 English as an Additional Language.

References

- Adler, Paul S., and Seok-Woo Kwon. 2002. “Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept.” The Academy of Management Review 27 (1): 17–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134367.

- Azorín, Cecilia. 2020. “Leading Networks.” School Leadership & Management 40 (2-3): 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1745396.

- Azorín, Cecilia, Alma Harris, and Michelle Jones. 2020. “Taking a Distributed Perspective on Leading Professional Learning Networks.” School Leadership & Management 40 (2-3): 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1647418.

- Azorín, Cecilia M., and Daniel Muijs. 2017. “Networks and Collaboration in Spanish Education Policy.” Educational Research 59 (3): 273–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2017.1341817.

- Baron, S., J. Field, and T. Schuller. 2000. Social Capital: Critical Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bassey, Michael. 1999. Case Study Research in Educational Settings. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1979. Algeria 1960.The Disenchantment of the World, the Sense of Honour, the World Reversed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1997. “The Forms of Capital.” In Education: Culture, Economy, and Society, edited by A. H. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown, and A. Stuart Wells, 46–58. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., and J. C. Passeron. 1979. Inheritors: French Students and Their Relation to Culture. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Bourke, R. 2022. “How Do School Networks Operate to Support DEIS Schools: A Case study Analysis of Two Transforming Education Through Dialogue Facilitated School Networks.” PhD, University of Limerick.

- Bridwell-Mitchell, E. N., and North Cooc. 2016. “The Ties That Bind How Social Capital Is Forged and Forfeited in Teacher Communities.” Educational Researcher 45: 7–17. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X16632191.

- Brown, C. D., and J. E. Flood. 2019. Formalise, Prioritise and Mobilise: How School Leaders Secure the Benefits of Professional Learning Networks. UK: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. https://books.emeraldinsight.com/page/detail/Formalise-Prioritise-and-MobiliseFormalise,-Prioritise-and-Mobilise/?k=9781787697782.

- Brown, Chris, and Jane Flood. 2020. “Conquering the Professional Learning Network Labyrinth: What is Required from the Networked School Leader?” School Leadership & Management 40 (2-3): 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1731684.

- Brown, P., and H. Lauder. 2000. “Human Capital, Social Capital and Collective Intelligence.” In Social Capital Cirtical Perspectives, edited by S. Baron, J. Field, and T. Schuller, 226–242. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Burt, R. 1992. Structural Holes: The Social Nature of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cahill, Kevin. 2015. “Seeing the Wood from the Trees: A Critical Policy Analysis of Intersections Between Social Class Inequality and Education in Twenty-First Century Ireland.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 8 (2): 301–316.

- Cahill, Kevin, and Dan O’Sullivan. 2022. “Making a Difference in Educational Inequality: Reflections from Research and Practice.” Irish Educational Studies 41 (3): 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2085763.

- Chapman, Christopher. 2019. “From Hierarchies to Networks.” Journal of Educational Administration 57 (5): 554–570. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-12-2018-0222.

- Chapman, J., and D. Aspin. 2003. “Networks of Learning: A New Construct for Educational Provision and a New Strategy for Reform.” In Handbook of Educational Leadership and Management, edited by B. Davies, and J. West-Burnham, 653–659. London: Pearson Education.

- Chapman, Christopher, and Mark Hadfield. 2010a. “Realising the Potential of School-Based Networks.” Educational Research 52 (3): 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2010.504066.

- Chapman, C., and M. Hadfield. 2010b. “School-Based Networking for Educational Change.” In Second International Handbook of Educational Change, edited by A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, and D. Hopkins, 765–781. Springer Science + Business Media B.V.

- Church, Madeline, Mark Bitel, Kathleen Armstrong, Priyanthi Fernando, Helen Gould, Sally Joss, Manisha Marwaha-Diedrich, Ana Laura de la Torre, and Claudy Vouhé. 2002. Participation, Relationships and Dynamic Change: New Thinking on Evaluating the Work of International Networks. London: Development Planning Unit, University College London.

- Clancy, P. 2001. College Entry in Focus: A Fourth National Survey of Access to Higher Education. Dublin: Higher Education Authority.

- Coburn, Cynthia E., and Jennifer Lin Russell. 2008. “District Policy and Teachers’ Social Networks.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 30 (3): 203–235. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373708321829.

- Coleman, J. 1997. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” In Education: Culture, Economy and Society, edited by A. H. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown, and A. Stuart Wells, 80–95. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Council Teaching. 2016. Cosán: Framework for Teachers’ Learning. Maynooth: Teaching Council.

- Courtois, Aline. 2015. “'Thousands Waiting at our Gates': Moral Character, Legitimacy and Social Justice in Irish Elite Schools.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 36 (1): 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.967840.

- Courtois, Aline. 2018. Elite Schooling and Social Inequality. Power and Privilege in Ireland's Top Private Schools. London: Palgrave McMillan.

- Creswell. 2014. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 4th ed. London: SAGE.

- Delaney, E., S. McAteer, M. Delaney, G. McHugh, and B. O’Neill. 2023. PIRLS 2021: Reading Results for Ireland. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- Department of Education. 2017. DEIS Plan 2017. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

- Department of Education. 2017. Retention Rates of Pupils in Second Level Schools: 2010 Entry Cohort. Dublin: DoE.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2016. Action Plan for Education 2016-2019. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2017. DEIS Action Plan 2017. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

- Department of Education and Skills Inspectorate. 2016a. School Self-Evaluation Guidelines 2016-2020 Primary. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills Inspectorate.

- Department of Education and Skills Inspectorate. 2016b. School Self-Evaluation Guidelines 2016-2020 Post-Primary. Dublin: Inspectorate, Department of Education and Skills.

- Díaz-Gibson, Jordi, Mireia Civís Zaragoza, Alan J. Daly, Jordi Longás Mayayo, and Jordi Riera Romaní. 2017. “Networked Leadership in Educational Collaborative Networks.” Educational Management, Administration & Leadership 45 (6): 1040–1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216628532.

- Doyle, Gavin, and Elaine Keane. 2019. “‘Education Comes Second to Surviving’: Parental Perspectives on Their Child/Ren’s Early School Leaving in an Area Challenged by Marginalisation.” Irish Educational Studies 38 (1): 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2018.1512888.

- Drudy, Sheelagh, and Kathleen Lynch. 1993. Schools and Society in Ireland. Vol. Book, Whole. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

- Educational Disadvantage Committee. 2005. Moving Beyond Educational Disadvantage: Report of the Educational Disadvantage Committee 2002-2005. Dublin: Department of Education.

- Field, J. 2003. Social Capital. London/New York: Routledge.

- Fleming, Brian, and Judith Harford. 2023. “The DEIS Programme as a Policy Aimed at Combating Educational Disadvantage: Fit for Purpose?” Irish Educational Studies 42 (3): 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1964568.

- Fleming, B., J. Harford, and Á Hyland. 2022. “Reflecting on 100 Years of Educational Policy in Ireland: Was Equality Ever a Priority?” Irish Educational Studies 41 (3): 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2085765.

- Frawley, Denise. 2014. “Combating Educational Disadvantage Through Early Years and Primary School Investment.” Irish Educational Studies 33 (2): 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2014.920608.

- Fullan, M. 2019. Nuance: Why Some Leaders Succeed and Others Fail. California, USA: Corwin.

- Galvin, J., A. Higgins, and K. Mahony. 2009. Family, School, Community Educational Partnership: Academic Report. Limerick: Curriculum Development Unit, Mary Immaculate College.

- Gilleece, L., S. Neils, C. Fitzgerald, and J. Cosgrove. 2020. Reading, Mathematics and Science Achievement in DEIS Schools: Evidence from PISA 2018. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- Government of Ireland. 2019. Wellbeing Policy Statement and Framework for Practice 2018-2023. Revised October 2019. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

- Grootaert, C., D. Narayan, V. Nyhan Jones, and W. Woolcock. 2004. Measuring Social Capital: An Integrated Questionnaire. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank).

- Hadfield, M., and C. Chapman. 2009. Leading School-Based Networks. Oxon: Routledge.

- Harford, Judith, Áine Hyland, and Brian Fleming. 2022. Editorial, Irish Educational Studies 41 (3): 421–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2094650.

- Hargreaves, A. 1994. Changing Teachers, Changing Times: Teachers’ Work and Culture in the Postmodern Age. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Hargreaves, A., and M. Fullan. 2012. Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Harris, A. 2010. “Improving Schools in Challenging Contexts.” In Second International Handbook of Educational Change, edited by A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, and D. Hopkins, 693–706. New York: Springer Science + Business Media B.V.

- Harris, A., C. Azorín, and M. Jones. 2021. “Network Leadership: A new Educational Imperative?” International Journal of Leadership in Education 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2021.1919320.

- Harris, A., M. Jones, and J. B. Huffman, eds. 2018. Teachers Leading Educational Reform: The Power of Professional Learning Communities. New York: Routledge.

- Herrera-Pastor, David, Jesús Juárez, and Cristóbal Ruiz-Román. 2020. “Collaborative Leadership to Subvert Marginalisation: The Workings of a Socio-Educational Network in Los Asperones, Spain.” School Leadership & Management 40 (2-3): 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1699525.

- Higgins, A., A. Lyne, S. Power, and M. Murphy. 2021. Embracing Diversity Nurturing Integration Programme (EDNIP): Sharing the Story, Evolution, Model and Outcomes of a Research and Intervention Project in 5 DEIS Band 1 Primary Schools in Limerick 2017-2019. Limerick: Curriculum Development Unit, Mary Immaculate College.

- Higher Education Authority. 2015. National Plan for Equity of Access to Higher Education 2015-2019. Dublin: Higher Education Authority.

- Higher Education Authority. 2018. Progress on the National Access Plan and Priorities to 2021. Dublin: Higher Education Authority.

- Higher Education Authority. 2022. Access Plan. A Strategic Action Plan for Equity of Access Participation, and Success in Higher Education 2022-2028. Dublin: Higher Education Authority.

- Hopkins, D. 2003. Understanding Networks for Innovation in Policy and Practice. Paris: OECD.

- Jeffers, G., and C. Lillis. 2021. “Responding to Educational Inequality in Ireland; Harnessing Teachers’ Perspectives to Develop a Framework for Professional Conversations.” Educational Studies 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2021.1931043.

- Johnson, W., D. Lustick, and MinJeong Kim. 2011. “Teacher Professional Learning as the Growth of Social Capital.” Current Issues in Education 14 (3): 1–16.

- Jones, Michelle, and Alma Harris. 2014. “Principals Leading Successful Organisational Change: Building Social Capital Through Disciplined Professional Collaboration.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 27 (3): 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-07-2013-0116.

- Katz, Steven, Lorna Earl, Sonia Ben Jaafar, Susan Elgie, Leanne Foster, Judy Halbert, and Linda Kaser. 2008. “Learning Networks of Schools: The key Enablers of Successful Knowledge Communities.” McGill Journal of Education/Revue des Sciences de L'éducation de McGill 43 (2): 111–137.

- Kavanagh, L., S. Weir, and E. Moran. 2017. “The Evaluation of DEIS: Monitoring Achievement and Attitudes Among Urban Primary School Pupils from 2007 to 2016.” In Report to the Department of Education and Skills. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- Kellaghan, Thomas. 2001. “Towards a Definition of Educational Disadvantage.” The Irish Journal of Education 32: 3–22.

- Kennedy, M., and M. Power. 2010. ““The Smokescreen of Meritocracy”: Elite Education in Ireland and the Reproduction of Class Privilege.” Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies 8 (2): 26. http://www.jceps.com/wp-content/uploads/PDFs/08-2-08.pdf.

- Kerr, D., S. Aiston, K. White, M. Holland, and H. Grayson. 2003. Review of Networked Learning Communities. London: National Foundation for Educational Research.

- Kools, M., and L. Stoll. 2016. “What Makes a School a Learning Organisation?” OECD Education Working Papers No. 137. OECD (Paris: OECD Publishing).

- Kwon, Seok-Woo, and Paul S. Adler. 2014. “Social Capital: Maturation of a Field of Research.” The Academy of Management Review 39 (4): 412–422. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0210.

- Lareau, Annette. 2015. “Cultural Knowledge and Social Inequality.” American Sociological Review 80 (1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414565814.

- Leana, Carrie R., and Frits K. Pil. 2006. “Social Capital and Organizational Performance: Evidence from Urban Public Schools.” Organization Science 17 (3): 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0191.

- Li, Y. 2015. Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Social Capital. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lieberman, Ann. 1999. “Networks.” Journal of Staff Development 20 (3): 43–44.

- Lieberman, Ann, and Maureen Grolnick. 2005. “Educational Reform Networks: Changes in the Forms of Reform.” In Fundamental Change, edited by Michael Fullan, 40–59. Netherlands: Springer Netherlands.

- Lima, Jorge Ávila. 2010. “Thinking More Deeply About Networks in Education.” Journal of Educational Change 11 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9099-1.

- Lin, Nan. 1999. “Building a Network Theory of Social Capital.” Connections 22 (1): 21.

- Lynch, K. 2019. “Inequality in Education: What Educators Can and Cannot Change.” In The Sage Handbook of School Organisation, edited by C. James, D. Eddy-Spicer, M. Connelly, and S. Kruse. London: Sage.

- Lynch, K., and J. Baker. 2005. “Equality in Education: An Equality of Condition Perspective.” Theory and Research in Education 3 (2): 131–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878505053298.

- Lynch, K., and M. Crean. 2018. “Economic Inequality and Class Privilege in Education: Why Equality of Economic Condition is Essential for Equality of Opportunity.” In Education for All? The Legacy of Free Post-Primary Education in Ireland, edited by J. Hartford, 139–160. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Lynch, K., and A. Lodge. 2002. Equality and Power in Schools: Redistribution, Recognition and Representation. London, New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Mandell, M. 1999. “Community Collaborations: Working Through Network Structures.” Policy Studies Review 16 (1): 42–65.

- McAvinue, L. 2022. “The Social Contexts of Educational Disadvantage: Focus on the Neighbourhood.” Irish Educational Studies 41 (3): 487–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2093519.

- McCoy, S. 2021. “Educational Disadvantage. Evidence from Two Growing Up in Ireland Cohorts.” Leadership+. The professional voice of school leaders, 2.

- McCoy, S., and D. Byrne. 2011. “‘The Sooner the Better I Could get out of There’: Barriers to Higher Education Access in Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 30 (2): 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2011.569135.

- McCoy, S., D. Byrne, P. J. O’Connell, E. Kelly, and C. Doherty. 2010. Hidden Disadvantage? A Study of the Low Participation in Higher Education by the Non-Manual Group. Dublin: Higher Education Authority.

- McCoy, S., E. Smyth, and J. Banks. 2012. The Primary Classroom: Insights from the Growing Up in Ireland Study. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute.

- McLaughlin, Colleen, Kristine Black-Hawkins, and Donald McIntyre. 2004. Researching Teachers, Researching Schools, Researching Networks: A Summary of the Literature. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

- McNamara, E., A. Murray, D. O’ Mahoney, C. O'Reilly, E. Smyth, and D. Watson. 2021. Growing Up in Ireland National Longitudinal Study of Children: The Lives of 9 Year Olds of Cohort ‘08. Dublin: Government of Ireland.

- Merriam, Sharan B. 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Rev. and expanded ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Miles, Matthew B., A. M. Huberman, and Johnny. Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Mills, Carmen. 2008. “Reproduction and Transformation of Inequalities in Schooling: The Transformative Potential of the Theoretical Constructs of Bourdieu.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 29 (1): 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690701737481.

- Misztral, B. 1996. Trust in Modern Societies. Cambridge: Policy Press.

- Muijs, Daniel, Mel Ainscow, Chris Chapman, and Mel West. 2011. Collaboration and Networking in Education. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Muijs, Daniel, Mel West, and Mel Ainscow. 2010. “Why Network? Theoretical Perspectives on Networking.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 21 (1): 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450903569692.

- Mulford, B. 2010. “Recent Developments in the Field of Educational Leadership: The Challenge of Complexity.” In Second International Handbook of Educational Change, edited by A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, and D. Hopkins, 187–208. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Nahapiet, Janine, and Sumantra Ghoshal. 1998. “Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage.” The Academy of Management Review 23 (2): 242–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/259373.

- Neils, S., and L. Gileece. 2023. Ireland’s National Assessments of Mathematics and English Reading 2021: A Focus on Achievement in Urban DEIS Schools. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- O'Connell, O., D. Clancy, and S. McCoy. 2006. Who Went to College in 2004? A National Survey of Entrants to Higher Education. Dublin: Higher Education Authority.

- OECD. 2015. Improving Schools in Scotland. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2017. “What do We Know About Teachers’ Selection And Professional Development In High-Performing Countries?” PISA in Focus, No. 70. Paris.

- OECD. 2019. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OSCAILT. 2013. Report of Dormant Accounts Funded Scheme to Enable DEIS Schools in Limerick City to Maximise Community Use of Premises And Facilities, Limerick. https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Education-Reports/Report-of-the-Dormant-Accounts-Funded-Scheme-to-Enable-DEIS-Schools-in-Limerick-City-to-Maximise-Community-Use-of-Premises-and-Facilities.pdf.

- O’ Sullivan, D. 2005. Cultural Politics and Irish Education Since the 1950s: Policy Paradigms and Power. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration.

- Punch, Keith. 2009. Introduction to Research Methods in Education. London: SAGE.

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Vol. Book, Whole. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Pyrko, Igor, Viktor Dörfler, and Colin Eden. 2017. “Thinking Together: What Makes Communities of Practice Work?” Human Relations 70 (4): 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716661040.

- Pyrko, Igor, Viktor Dörfler, and Colin Eden. 2019. “Communities of Practice in Landscapes of Practice.” Management Learning 50 (4): 482–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507619860854.

- Rincón-Gallardo, Santiago. 2020. “Leading School Networks to Liberate Learning: Three Leadership Roles.” School Leadership & Management 40 (2-3): 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1702015.

- Rincón-Gallardo, Santiago, and Michael Fullan. 2016. “Essential Features of Effective Networks in Education.” Journal of Professional Capital and Community 1 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-09-2015-0007.

- Robson, Colin. 2011. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley.

- Scanlan, M. 2020. Pandemics, Epidemics and the Power of Metaphor. Teachers College Record.

- Scanlan, M., H. Jenkinson, P. Leahy, F. Powell, and O. Byrne. 2019. “How are we Going to do it?’ An Exploration of the Barriers to Access to Higher Education Amongst Young People from Disadvantaged Communities.” Irish Educational Studies 38 (3): 14.

- Schleicer, A. 2016. Teaching Excellence Through Professional Learning and Policy Reform: Lessons from Around the World. OECD. Paris: OECD.

- Sleegers, P., N. Moolenaar, and A. Daly. 2019. “The Interactional Nature of Schools as Social Organisations: Three Theoretical Perspectives.” In The Sage Handbook of School Organisation, edited by C. James, D. Eddiy-Spicer, M. Connelly, and S. Kruse. London: Sage. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/the-sage-handbook-of-school-organization/book256513.

- Smyth, E. 2018a. “Educational Inequality: Is ‘Free Education’ Enough?” In Education for all? The Legacy of Free Post-Primary Education in Ireland, edited by J. Hartford, 117–137. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Smyth, E. 2018b. “Working at a Different Level? Curriculum Differentiation in Irish Lower Secondary Education.” Oxford Review of Education 44 (1): 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.1409967.

- Smyth, E., and S. McCoy. 2009. Investing in Education: Combating Educational Disadvantage. Dublin: ESRI.

- Smyth, E., S. McCoy, and G. Kingston. 2015. Learning from the Evaluation of DEIS. Economic Social and Research Institution (Dublin). https://www.esri.ie/publications/learning-from-the-evaluation-of-deis.

- Stake, Robert E. 1995. The art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Stevenson, H. 2023. “Professional Learning and Development: Fit for Purpose in an age of Crises?” Professional Development in Education 49 (3): 399–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2023.2207332.

- Stoll, L. 2010. “Connecting Learning Communities: Capacity Building for Systemic Change.” In Second International Handbook of Educational Change, edited by A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, and D. Hopkins, 469–484. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Weir, S., L. Kavanagh, C. Kelleher, and E. Moran. 2017. Addressing Educational Disadvantage. A Review of Evidence from the International Literature and of Strategy in Ireland: An Update Since 2005. Dublin: Educational Research Centre.

- Wenger, Etienne. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wohlstetter, P., C. L. Malloy, D. Chau, and J. L. Polhemus. 2003. “Improving Schools Through Networks: A new Approach to Urban School Reform.” Educational Policy 17 (4): 399–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904803254961.

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th ed. London: SAGE.