ABSTRACT

This study examines teachers’ experiences of transition at different points in time over a two-year period to encapsulate their journey to becoming a qualified teacher. Six novice teachers participated in a study in their final year of university through to their first year as a newly qualified teacher. Reflective journals, one-to-one interviews and qualitative surveys formed that database for reflexive thematic analysis and theme maps. Schlossberg’s indicators for identifying transition were then related to the analysed data to establish the type of transition experienced by teachers. Findings from the study shed light on the overlapping nature of transitions experienced by novice teachers and highlight opportunities for professional learning to aid for the smoothening of these transitions for aspiring teachers.

Introduction and purpose

This study is contextualised in terms of the international historical need to provide evidence-based professional learning to contribute to high-quality teaching. Evidence-based teacher professional learning is central to fostering adaptive teaching practices that cater for diverse student needs and strive to achieve learning outcomes tailored for the twenty-first century (Timperley and Alton-Lee Citation2008). One way of collecting evidence to support professional learning is through learning from the experiences of others using the lens of our own encounters to produce rich insight and perspective for our practice (Brookfield Citation1998; Harland Citation2014). For example, if you are looking for a good hairdresser, it is likely that you would ask a trusted friend for a recommendation even if you have different hair colour or length. In the same way, we can learn lessons from the experiences (discover patterns emerging from experience (Thomas Citation2011)) of other teachers transitioning to the workplace in an effort to support future novice teachers. Considering the process of how teachers transition into the workplace (both professionally and personally) can highlight opportunities for embedding meaningful professional learning opportunities or understand the roadblocks encountered by novices that may inhibit them from moving to the next transition successfully e.g. becoming a qualified teacher and contributing to quality educational experiences for their students.

Much of the research pertaining to supporting novice teachers, centres around creating specific support for teachers to understand student reasoning, teaching strategies and curriculum knowledge (Angell, Ryder, and Scott Citation2005), negotiate their status as a novice teacher (Long et al. Citation2012), develop their pedagogical content knowledge (Loughran, Mulhall, and Berry Citation2004) or address many of the other constraints faced in their early years of qualification. The dynamic nature of teaching as a profession (constantly presenting new challenges and responsible for the needs of others) coupled with all of life’s other obstacles or elating experiences suggests the need to capture more than just one dimension of a teacher’s experience to fully understand their needs and support them in a meaningful way. Cobb (Citation2022) encapsulates some of this journey, revealing that teacher identity, resilience and agency affect how teachers respond to transition into the teaching profession (Cobb Citation2022).

We must consider, however, that the aforementioned studies are focussed on specific factors affecting transition, with the assumption that the type of transition is already determined, that transitions are obvious and clear. As Schlossberg (Citation1981) highlights, often different people experience different types of transitions depending on their individual circumstances. What may be a major career transition for one teacher may be less significant to another teacher who is experiencing a significant personal change or event (Schlossberg Citation1981). Collecting evidence systematically, to establish the transition being experienced by teachers, may help to enhance interventions (Barclay Citation2015) and suggest time-sensitive and unique professional supports to specific cohorts of teachers, as is common practice in nursing education (Wall, Fetherston, and Browne Citation2018).

Theoretical considerations

Workplace transitions are usually assumed to take place when [physically] leaving one establishment and starting in another. This research focusses on teachers’ experience of transition over a continuum (not assuming a transition to occur at a specific time) and examines what factors influence novice teacher transitions into the workplace and at what stage in their career development they occur. The study of transition in teacher education is reported in the literature at each level of teacher education (early childhood, primary and second-level). Novice teachers often experience difficulty in separating their experiences of being taught to learning how to teach (Hopper Citation1999). This is corroborated in a study of primary science teachers where Mulholland and Wallace (Citation2003) use a ‘border crossings’ theoretical framework to inspect their transition from pre-service to in-service teaching, from non-science to science and from other school subjects to school science. They observed that past experiences and understandings largely influenced their crossing the border from the sub-culture of the university to the sub-culture of the primary school (Mulholland and Wallace Citation2003). Tynjala and Heikkinen (Citation2011, 26) reviewed research related to novice teacher transition and reported similar challenges as graduates from other professions also related to threat of unemployment, feeling of inadequate competences, decreased self-efficacy and increased stress. They understand that teacher attrition, belonging in the work community and learning on the job are all aspects of teaching that novice teachers face in their beginning years of teaching (Tynjala and Heikkinen Citation2011). These studies focus mostly on specific aspects of professional learning, or novice teachers’ use of tools and strategies, considered at a snapshot in time, rather than a holistic exploration (using a systematic approach) of teacher transition over a sustained period of time.

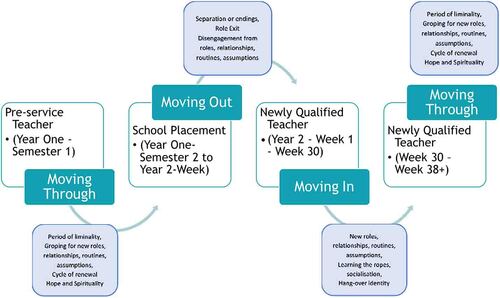

Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson (Citation2006, 40) suggest that to examine people experiencing a transition is ‘to study them at several points in time’. They present three stages for understanding the transition process, moving in, moving through and moving out or moving in again.

Individuals moving in, to a transition share common needs such as becoming familiar with new roles, rules, norms and expectations of the new system (Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson Citation2006). In the context of a work transition specifically, the individual is required to understand the expectations of peers and supervisors and become accustomed to the company/industry norms. This may entail learning new skills and this new role can result in feeling marginalised. At the same time, there is an expectation that the individual will experience joy, at the prospect of a new job. During this stage, the individual needs to feel supported and challenged in balancing work duties and other parts of their lives (Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson Citation2006).

Once the individual has learned the ropes of the new role, they begin to move through the transition. This period is seen to evoke reflection and re-evaluation of the transition. During the moving-through phase of a work transition, a person initially goes through a period of exploration and innovation. This is followed by a period of time during which the person focusses on extending and improving skills. Finally, during the moving-through phase, the individual must embrace the ‘new and different’ in order to transform and move to successful fulfilment and reinventing of the future (Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson Citation2006).

Moving out of a transition can be viewed at the end of a transition period or at the start of a new transition (exiting a transition in order to embrace a new change). Goodman, Schlossberg and Anderson (Citation2006) draw on research from a workshop for people in transition to summarise the shared experiences of individuals moving out of a transition. They report that during this phase the person can display feelings of mourning or disbelief for the job change or loss, to resolution and accepting the reality of the situation (Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson Citation2006).

Research questions

Examining the experiences of novice teachers as they engage in pre-service teacher education, participate in school placement or begin their journey as a newly qualified teacher, can all help to inform teacher professional learning at each stage of novice teacher professional development. Investigating the many experiences of novice teachers, as a trajectory of a journey with no beginning or end, to identify patterns of change in their personal and professional lives, may be a new approach to examine the experiences of newly qualified teachers entering the workplace. In particular, identifying the type of transition (be it a personal transition or career transition) experienced by teachers as they leave pre-service teacher education and become in-service teachers.

This study aims to examine teachers’ experiences of transition at different points in time to encapsulate their journey to becoming a qualified teacher and explores the research questions:

What type of transition is experienced by novice teachers as they become newly qualified teachers?

What are teachers’ experiences of the transitions associated with becoming a novice physics teacher?

Methodology

This article presents a comparative analysis of novice teachers’ experiences at different points in time over a two-year period. Schlossberg’s transition theory was applied to the data set (reflective journals, interviews and qualitative surveys) in order to identify the type of transition (moving in, moving through or moving out) that was common to novice teachers.

Participants

The participants included in this study were six novice physics teachers. The sample was purposefully sought (Merriam and Tisdell Citation2016) to address the research question, however, the sample was also convenient to the researcher who taught a final year Physics Methodologies module to the participants as part of their BSc in Science Education. In the case of this study, the teachers’ discipline was not particularly interrogated with respect to transition, however, the authors felt it necessary to distinguish the teacher discipline should further research in the field wish to focus on this dimension.

Novice teachers in the context of this study referred to the teachers in their final year of pre-service teacher education through to their first year as a newly qualified professional teacher. Ethical approval was sought and granted from Dublin City University for the novice teachers to investigate their experiences at the end of school placement and in their first year of teaching (DCUREC2020/093).

Research design

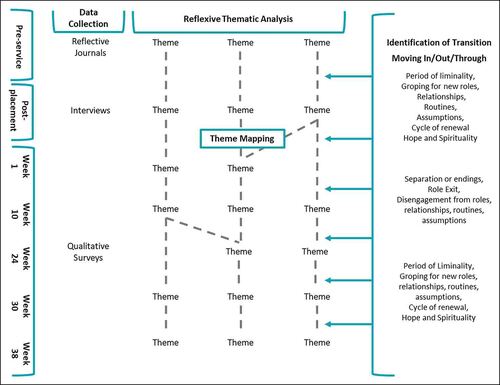

This study (see ) describes research carried out over two years (Year 1 and Year 2). The research began in the final year (4th year) of pre-service teachers’ BSc in Science Education. All six of the novice teachers participating in this study had chosen pathways to qualify as physics and mathematics teachers and completed methodology modules for both physics and mathematics in semester one of their final year. The Physics Methodologies module (from which data for this study was collected) was delivered over three hours per week for 12 weeks (see Figure 1) During the second semester of final year, the teachers completed a 14-week school-based placement and gained experience teaching physics and mathematics at lower and upper secondary level. Research Practice Partnerships (RPPs) were formed at the end of teachers’ school placement experience (see ). The purpose of RPPs was to reconnect novice teachers with their peers (of similar subject discipline) and link theory to practice by building on key findings in the literature to address the novice teachers’ problems of practice. The RPP meetings took place four times during the novice teachers first year of teaching. Six novice physics teachers and two science education researchers (Researcher and Supervisor) joined the RPP voluntarily and the first meeting focussed on negotiating norms and setting expectations for the year ahead (Penuel and Gallagher Citation2017). It was important that all members shared their common goals in order to have equal buy-in from each partner and build a mutualistic relationship.

Data collection

Reflective Journals: Merriam and Tisdell (Citation2016) emphasises the usefulness of textual data that does not intervene with the participant as they document their experiences. Novice teachers engaged deeply in reflective practice as part of Physics Methodologies module over 12 weeks in the first semester of their final year. Teachers were introduced to: the role of reflection in teaching and learning (Moon Citation2004), reflecting on their reflections and assessing their reflections (Binks et al. Citation2009) and writing critically (Larrivee Citation2000). Textual data in the form of 60 reflective journals were collected at the end of each weekly lecture that ranged from approximately 500–2000 words.

Interviews: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with the teachers at the end of their final teaching placement in university. There were 9 questions in total and the interview probed; teachers’ experiences of school placement, supports available to pre-service teachers during their school placement, opportunities for collaboration with other teachers, barriers to teaching physics, difficult physics concepts (as a teacher and as a learner), general advice for future teachers and any concerns they may have starting a new job.

Surveys: The six novice teachers were invited to complete qualitative surveys in the first week of teaching as a newly qualified teacher (NQT) and at 4 other points throughout their first year of teaching during research practice partnership (RPP) meetings.Footnote1 The qualitative surveys consisted of four open-ended questions that aligned with the research question and were completed online in Google Forms. The qualitative questions probed teachers on what challenges have they faced [up to now], what they were excited for [in the year ahead], concerns they may have [in the year ahead] and resolutions they will try and make [before the next meeting]. Thirty-five qualitative surveys were collected in total throughout the teachers’ first year as NQTs.

Data analysis

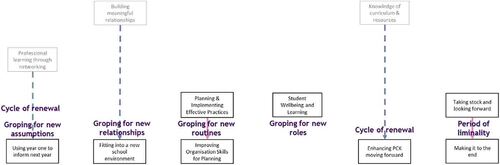

Reflexive thematic analysis was carried out on each of the data sets described in the data collection above, to identify themes generated around centralising concepts (Braun and Clarke Citation2019). These themes are described in more detail in another paper (O’Neill Citation2022), however a summarised version of the themes can be found in Appendix. A theme map (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) was then created with all of the themes generated at each point in time over the two years of the study, in order to conceptualise the teachers’ experience moving from pre-service teacher to newly qualified teacher See below.

A descriptive relation (Robinson Citation2011) was drawn between the inductive themes of the data set and the themes from Schlossberg’s transition theory to create joined up description within analysis. This was done by relating the indicators from Schlossberg’s Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson’s (Citation2006) ‘Approaching Transitions’ model (see Moving In/Out/Through Indicators in ) to the themes at each data collection point. This was used to identify the teachers’ transition type: moving in, moving through or moving out and examine relationships between the transitions as seen in .

A transition was observed when all of the themes could be mapped to the indicators of that theme. For example, in , it can be seen that the themes can be related with the indicators for moving through a transition which in turn can be further related to concrete contextualised examples of the themes and the participant quote (Robinson Citation2011, 201).

Findings

Teachers’ journeys from pre-service teacher to newly qualified teacher highlighted a ‘moving through’ transition during their pre-service teacher education, and teachers then began to ‘move out’ during their school placement as they transitioned from learner to teacher (see ). As the teachers came to the end of their school placement experience a shift towards ‘moving in’ was observed. It was not until about week 30 of their first year as a newly qualified teacher that they ‘moved through’ the transition for the remainder of the year (see ).

Figure 4. Novice teacher’s transition identification in their final year of university and first year teaching as a newly qualified teacher.Footnote2

Moving through

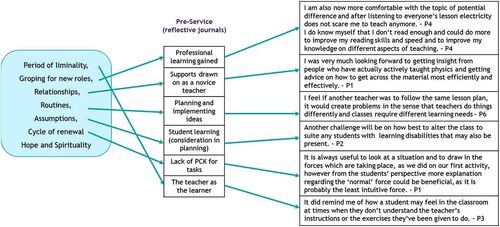

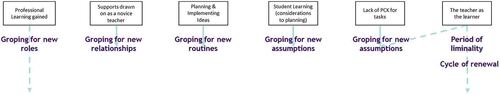

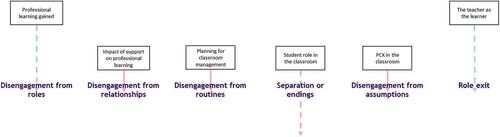

The first transition that teachers experienced was observed when there was a shift in themes between the data sets at the end of final semester of structured lectures [reflective journals] to their school placement block [interviews] (school placement took place predominantly in school with some evening lectures in university), as in . The themes summarised during this point of teachers’ journey were professional learning gained, supports drawn on as a novice teacher, planning and implementing ideas, student learning (considerations for planning), lack of PCK for tasks and the teacher as the learner (further detail of themes in generation of these themes in O’Neill (Citation2022)).

These themes suggested that teachers were moving through a transition as they began looking for New Roles as practicing teachers (Nguyen Citation2017). Teachers described the professional learning they had gained such as confidence teaching a particular topic, ‘I am also now more comfortable with the topic of potential difference and after listening to everyone’s lesson electricity does not scare me to teach anymore’ – Teacher 4. They also recognised other opportunities to improve their professional learning (reading literature), ‘I do know myself that I don’t read enough and could do more to improve my reading skills and speed and to improve my knowledge on different aspects of teaching.’ – Teacher 4.

Teachers described the New Relationships they would like to explore during this transition, such as connecting with teachers who were actively teaching the curriculum, ‘I was very much looking forward to getting insight from people who have actually actively taught physics’ – Teacher 1. Pietsch and Williamson (Citation2010) suggest that novice teachers should be encouraged to collaborate with experienced colleagues at ‘point-of-need’ to develop novices’ professional identity and feel like they belong within the school community(Pietsch and Williamson Citation2010).

Within this transition the themes reflected that the teachers had reached a point where they could broadly identify many different aspects of being a teacher (planning lessons, student learning, pedagogical content knowledge) but this knowledge was also limited by their lack of classroom experience (implementing plans, catering for different learner types, knowledge of curriculum – Groping for New Routines). Most of their discussion is centred around hypothetical scenarios., ‘I feel if another teacher was to follow the same lesson plan, it would create problems in the sense that teachers do things differently and classes require different learning needs’ – Teacher 6.

In some cases, teachers began projecting what experience they would expect to have and often this left them wondering if they were prepared to become teachers ‘And another problem we had was coming up with the questions for IBL (inquiry based learning) and predicting what the students may do. This is very hard when you have never thought the topic before.’ – Teacher 4 (Groping for New Assumptions).

There were many points during this time period that teachers exhibited critical reflection about teaching approaches. During their methodologies module they discussed effective teaching approaches, different adaptations they could make to teaching approaches, suitability of teaching approaches and even analysed the thinking (lecturer’s thinking) for choosing to teach a class in a particular way (Groping for new assumptions). McLean and Price (Citation2019) raise a similar interesting finding with pre-service tutors as they exhibit idealistic views based on their own learning experiences in the early stages of their training.

The most predominant aspect of identifying this transition was teachers’ comments that aligned with a ‘Period of Liminality’ as outlined by Schlossberg and colleagues (Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson Citation2006). It could be seen that the teachers were experiencing teaching as a learner, probably (could only be determined by collecting data earlier in their journey) throughout their university degree and were now beginning to reach a point of knowledge saturation as a ‘learner’ as they focussed more on challenges they may encounter in future, ‘Another challenge will be on how best to alter the class to suit any students with learning disabilities that may also be present’ – Teacher 2. Here, it is evident that providing teachers with space actively reflect can help them to enhance their practice and grow professionally (Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020).

Throughout the duration of this study, it was observed that time and experience were needed for teachers to understand their role in the classroom associated with the Cycle of Renewal indicator. Teachers highlighted their understanding of the student role as a consequence of their own learning as a learner. They focussed here on the learner experience and putting themselves in the shoes of the student. It was clear that teachers still felt, in part, a learner as they describe their lack of pedagogical content knowledge. These lived experiences of novice teachers provided insights into some of the tensions that they must unravel as part of discovering their teacher identity. Bullock (Citation2017) describes findings from a self-study in which a student teacher is provided with extended experiences of teaching the same classes with no feedback early on in order to form relationships and focus on the students versus an experience of teaching ‘learned in the messiness of unexpected experiences’ (p.188). Here, he refers to the ‘Freedom with Foundation’ for teachers to begin to develop their teacher identity (what their role is in the classroom) and deal with the dynamic aspects of teaching be it; controlled and well thought out, or sudden and dealing with complex situations (Bullock Citation2017).

Moving out

Teachers began to move out of the previous transition (moving through) during their school placement (Semester 2) (see ). The summarised themes for this point of the data collection were; impact of support on professional learning, planning for classroom management, student role in the classroom and PCK in the classroom. Here, teachers were exiting their role as the learner and beginning to think about aspects of teaching in the context of their teaching experiences. This was evident in all of the themes generated at the end of the novice teachers school placement experience.

Professional learning was not a concern for teachers (disengagement from routines) at this point as they juggled between the old and new roles and relationships that came with moving out of the transition. For example, rather than broadly considering planning and implementing ideas, teachers were now concerned about how to plan around classroom management and control issues related to behaviour.

Teachers began to disengage from the supportive relationships of their classmates as they felt their peers were also under the same pressure (as they were) and they didn’t want to add to this, ‘Not really [use peers as support], cause em, I suppose I didn’t want to dive in because we were all sorta up in the air a bit,’ – Teacher 3. Instead, teachers discussed how the support from their cooperating teachers influenced their experience of classroom practice, ‘My coop teacher was really good, he sorta, every time I went to him with an issue he was like ‘oh you can try this,’ – Teacher 3.

The more teachers integrated into the school community during their school placement the more they disengaged from their idealistic routines when planning for ‘theoretical classes’, ‘..so I suppose I had to take a step back in the level I was giving them and go through things, like give more time to things that I thought would be done in ten minutes.’ – Teacher 4. this aligns with the literature as teachers are faced with the realities of teaching as their new point of reference (McLean and Price Citation2019).

Evidence from teacher interviews after school placement also highlighted that teachers’ attention shifted to planning for classroom management, similar to that reported by Britt (Citation1997). Teachers still remained adventurous in trying new approaches to see what worked effectively, however, the depth of reflection seen in the previous transition seemed to become less during this moving out transition. Tammets, Pata, and Eisenschmidt (Citation2019) highlight the value of fostering reflection for novice teachers’ post-university in order to highlight learning and knowledge-building practices that could be supported in the wider school community (Tammets, Pata, and Eisenschmidt Citation2019).

Teachers again discussed the teacher and student role in the classroom. However, it was evident that teachers’ view of what they thought the teacher’s role was in the classroom began to shift as a result of the experience they were gaining. This finding indicated a ‘separation or ending’ in teacher old beliefs when immersed in university-based modules. Teachers were now considering how their role (as a teacher) in the classroom could facilitate student learning and how they could plan around engaging students in meaningful learning. They were beginning to discuss balancing teacher and student roles so that students could be more active in their learning (‘Now they were good with inquiry based and I’m not going to tell you the answer you’s have to go find the answer and stuff like that,’ – Teacher 1), but it was difficult to say at this point if teachers were implementing this approach into their role as a teacher during their school placement. School placement gave teachers a space to reflect on their teaching strategies and bring their own experiences into practice. Ultimately learning to teach is a complex issue and is reported in much of the literature (Bullock Citation2017; Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020).

Rather than being concerned about their own pedagogical content knowledge teachers were taking stock of the knowledge and experience needed to ‘get through’ teaching (implementing restorative practice and keeping track of student progress). ‘I was sitting at the computer for quite a while trying to fully get my head around what needed to be taught and how I was going to teach it that sort of thing,’ – Teacher 1. This can also be seen clearly as one teacher describes their experience with having to adapt teaching strategies and planning to the changing circumstances that impeded on student attendance in transition year (changing assumptions).

‘I was given a transition year group and told just do whatever you want with them. And so, I started doing physics and … .. I suppose you didn’t know what students, there could be a day when only two students come to class or a day where there could be twenty. So, I was really trying to do it [plan each lesson] as something that didn’t have to be continuous.’ – Teacher 5

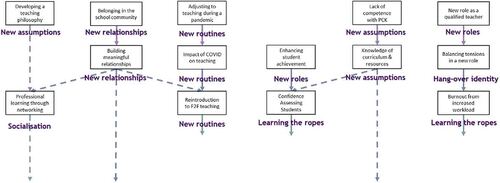

Moving in (but still moving out)

During teachers’ first week as newly qualified teachers there was a clear adoption of new roles, relationships, routines and assumptions indicating an entry into a new transition (moving in) and was evident from week 1 of their first week as a newly qualified teacher through to week 30 (). In , the themes generated from teacher data were summarised as; developing a teaching philosophy, professional learning through networking, belonging in the school community, building meaningful relationships, enhancing student achievement, confidence assessing students, lack of competence with PCK, knowledge of curriculum and resources. COVID-19 began to emerge from the themes as teachers discussed adjusting to teaching during a pandemic, the impact of OCVID on teaching and a reintroduction to face-to-face teaching. Finally, these generated also reflected participant’s new role as a teacher, balancing tensions in a new role and burnout from increased workload.

In this moving in transition, teachers’ professional learning evolved over the 30 weeks from identifying what they had learned in the classroom to reflecting on how they could continuously develop their knowledge, through their philosophy of teaching and networking with others (socialisation). ‘[I hope to] continue having learning discussions with other teachers of all subjects on tips for differentiation’ – Teacher 5.

Teachers began to notice their belonging in the school community and the relationships they had with their colleagues in this transition. It was evident that they were beginning to think about building new and meaningful relationships with colleagues and students, ‘I am looking forward to building good relationships with my new colleagues, getting the chance to work with like-minded people’ – Teacher 1. Supports in the context of pre-service teacher education were also discussed by teachers. During their school placement and first year of teaching, teachers felt that their experience from university was quite theoretical and there was less focus on the difficulties or the implementation of particular teaching approaches such as inquiry-based learning (IBL). Lack of time, resources to prepare for IBL, managing group work, curriculum delivery, assessment and accountability are reported in the literature to be the constraints that practicing science teachers experience adopting IBL approaches (Romero-Ariza et al. Citation2020) and which resonated with the cohort in this study.

Adjusting to new norms that resulted from teaching through a pandemic was a large focus of teachers’ planning and implementation as they moved between online teaching and face-to-face teaching. These new routines were a predominant focus of teachers’ reflections throughout their first year teaching. Teachers were continuously adapting to online and face-to-face teaching according to changing government guidelines, and this in turn impacted the routines they implemented in the classroom, ‘I’m concerned about the transition from online learning to school … how to deal with students who have fallen behind,’ – Teacher 4. These adjustments also led to more responsibility on teachers to implement continuous based assessments and accredited grades for their students, adding yet another new role to their experience as a novice (high stakes exam assessor).

Throughout this phase of new assumptions, it could be seen that teachers were assessing and reassessing their knowledge for teaching as they balanced the tensions in their new role and managed burnout from an increased workload. They experienced a lack of competence when compared to their fellow experienced teachers, ‘[Excited] To grow both my skills and my reputation. [Challenged by] Keeping up with my experienced teacher’s pace’ – Teacher 1. As time progressed teachers became concerned with their knowledge of curriculum and resources. They reported being unsure if they were considering the depth of treatment of the curriculum correctly and whether their pacing would ensure the course would be complete in time, ‘I'm concerned on occasion that I am missing elements of content within topics’ – Teacher 6. Research suggests that methods for developing content competencies are needed in teacher preparation (Buabeng, Conner, and Winter Citation2015).

Once teachers had integrated into their new school, reflection on practice and critical thinking about teaching approaches were overshadowed by increased workload and teaching during a pandemic. Here, teachers were experiencing, new roles (responsibility of a qualified teacher), hang-over identity (still a learner) and learning the ropes (which manifested through their experiencing burn-out). It was evident here, that teachers were still moving out of their previous transition as they had to become accustomed to being accountable for their students and were no longer shielded by their cooperating teachers. ‘Practice shock’ is the term given to the period of time that beginning teachers experience in their first job, that is much different than their expectations of pre-service teacher education and is focussed on survival in the classroom rather than their ideals of teaching (Stokking et al. Citation2003, 340). This was very evident in the case of the six novice teachers in this study.

Moving through

After week 30, there was a notable shift in teachers’ outlook on their experiences (as in ). The themes summarised at this point of teachers’ journey were; using year one to inform the next year, fitting into a new school environment, planning and implementing effective practices, improving organisational skills, student wellbeing and learning, enhancing PCK moving forward, taking stock and looking forward and making it to the end. Here, the relation of indicators onto themes suggests that teachers were entering a moving through transition as they began taking stock of their experiences so far and were looking forward to what was coming next. It was evident that the end of the school year had come with a sense of accomplishment for these teachers.

It was obvious from the themes, that teachers were returning full circle as described by the cycle of renewal (getting ready, to launching and plateauing, to sorting things out) (Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson Citation2006). The themes identified at this period suggest that teachers are now using their past experiences to inform their approach for the next school year, ‘I’m excited to start fresh out next year and take what I have learned this year and apply it’ – Teacher 4. The themes reflected teachers’ future ambitions of enhancing their PCK, learning from the year that had passed and improving their planning and organisation skills, ‘Using the time off in summer to further improve my teaching practices (CPD workshops, creating resources, etc.)’ – Teacher 3.

However, teachers were also concerned about having to move to school and fit into a new school environment (new relationships) or had to deal with the uncertainty of being kept on in their current school, ‘A challenge will be fitting in to a new school environment and also getting to know another set of students’ – Teacher 1. This is similarly reported by researchers who suggest that relationships with other professionals in their field are critical to a teachers’ professional growth (Wilson, Schweingruber, and Nielsen Citation2016, 178).

Teachers outlined the new routines that they would like to focus on moving forward such as planning and implementing effective practices and improving their organisation skills, ‘I’m committed to keeping my drive and students results more organised as the predicted grades this year really showed me my own organisation flaws’ – Teacher 4. Teachers also discussed the more holistic aspects of student wellbeing, which exhibited their understanding of teaching to be concerned with wider issues other than that of content and assessment, ‘[I am concerned about] getting students back into a routine after being away from school for so long’ – Teacher 3. This finding aligns with literature that describes graduate teachers’ perceptions of teaching as a combination of ‘the nurturer’ and the ‘moral agent’ (Ezer, Gilat, and Sagee Citation2010).

This transition would suggest that teachers had begun to overcome the challenges that faced them earlier in the school year as, again, a period of liminality is observed across the themes. Teachers began to take stock of their experiences and were focussed on making it to the end of the school year, ‘[I’m excited about] Finish up my first year’ – Teacher 6. However, the transition is somewhat incomplete, similar to the first transition, as it is necessary to see where teachers are going next. The suggestion of teachers’ ‘groping for new roles’ in a ‘period of liminality’ proposes a shift away from the moving in transition and onto a new transition, ‘[I am excited about] Repeating the process again next year and apply what new things/skills I learned during my first year out’ – Teacher 3.

Discussion

This study focussed on capturing the experiences of novice physics teachers over a two-year period, from their final year as a pre-service teacher to their first year as a newly qualified teacher. The research aimed to investigate if there are indicators of transitions occurring during this time period in order to inform the research questions:

What type of transition is experienced by novice teachers as they become newly qualified teachers?

What are teachers’ experiences of the transitions associated with becoming a novice physics teacher?

Observation 1 – Identifying transitions

The application of transition theory to teachers’ experiences collected over two years provided a structured and holistic method to examine novice physics teachers’ experiences. Schlossberg (Citation1981) highlights that in order to examine an individual as they experience a transition, the transition must not be assumed. Transitions can be anticipated, unanticipated, an event or non-event but it must be characterised by the individual in order to be considered a transition (Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson Citation2006). This study’s method and findings were cognisant of this underlying principle and provided an evidence-based approach to identify teacher transitions through the teacher voice. The study highlights the novel way that trends in themes, generated from teacher data, can inform the transitions that teachers are undergoing at a specific moment in time. Here, the teacher’s journey as a novice has been documented and the teacher voice is at the centre of the findings.

The findings presented in this study highlight trends in teachers’ experiences and identify multiple transitions that overlap and span the entirety of their final year in university and first year of teaching. At the end of teachers’ formal university lectures (in Semester 1), the study shows them moving through a transition, they were becoming used to the routines in college and anticipating the next step of experiencing classroom practice. During their school placement block, in the final semester of their degree, teachers began to exit their role as a learner and begin their journey as a teacher. However, this moving out phase of the transition was not instantaneous and overlapped for some time with teachers experience of moving into their role as a newly qualified teacher (from final semester of university to the end of their first year teaching). In week 30 of teaching as a newly qualified teacher, the participants began to describe their cycle of renewal, indicating moving through a transition again. Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson (Citation2006) outline that for this reason (variable and changing circumstances of the individual during a transition), transition theory provides a structural approach to examine experiences rather than considering them ‘anew’. The findings from this study also indicate that the transitions for these newly qualified teachers are ongoing and may extend for several years. This can be explained through the understanding of transitions as a process over time with no beginning or end (Goodman, Schlossberg, and Anderson Citation2006).

Observation 2 – Novice teacher experience of transition

Examination of themes generated from teacher data indicates specific moments of intervention needed by teachers to smooth the transition from pre-service to in-service teaching. The application of this model can help researchers understand at which developmental stage novice teachers are in their career and therefore contribute to differentiated support for teachers during their transition from pre-service teacher to newly qualified teacher as is called for in the research (Zhukova Citation2018, 111). Supporting novice teachers as they navigate changing roles, develop new relationships, transform prior assumptions and trial new routines during their early years of teaching are presented in this study as considerations for designing professional learning opportunities. The themes discussed by teachers in this study are similar to those reported in the literature as challenges faced by teachers in the first years of their teaching (Fantilli and McDougall Citation2009, 823). However, the organisation of these challenges and experiences (as shown in this study using transition theory) can be helpful in identifying aspects of professional learning that are relevant to novice physics teachers at a specific time in their career (according to the lived experiences of teachers). Through the examination of teachers’ experiences over a two-year period, it is apparent that their problems of practice change and evolve over time, with some of these issues dissipating with experience (e.g. building meaningful relationships) and others remaining persistent throughout the year (enhancing PCK). Etkina (Citation2010) describes a physics teacher preparation programme that embeds physics-specific clinical practice. Here, PSTs engage in an ‘active process of knowledge construction’ to enhance their PCK through a cognitive apprenticeship (teaching that is scaffolded and supported by a coach) (Etkina Citation2010).

Helping teachers to manage their expectations before they enter school placement and in their early weeks of the first year out teaching (to relieve practice shock) (Rieg, Paquette, and Chen Citation2007), assigning teachers with subject-specific mentors that can advise on content and curriculum needs on an ongoing basis (Nguyen Citation2017) and facilitating opportunities for novice teachers to network outside of their own school context (Mercieca Citation2018), are just some of the solutions that could be implemented to address the problems of practice outlined by teachers in this study and smooth their transition from pre-service teacher education to in-service teaching. Findings from this study also suggest that teachers require a space to reflect on their practice and grow professionally (Ellis, Alonzo, and Nguyen Citation2020).

Conclusion

The findings presented in this study emphasises the teacher voice, to highlight the gaps in novice teacher professional learning and add another perspective to the call for solutions to address gaps in pre-service teacher education (Gray, McDonald, and Stroupe Citation2022). The application of Schlossberg’s transition theory to identify a transition, is a novel approach to systematically examine the experiences of novice physics teachers entering the workplace. The organisation of teacher challenges and experiences (as shown in this study using transition theory) can be helpful in identifying aspects of professional learning that are relevant to novice physics teachers at a specific time in their career (according to the lived experiences of teachers) through enhanced professional learning interventions (Barclay Citation2015).

Limitations and future research

It is worth noting that the data reported on in this study provided evidence in the context of the participant as a teacher (as opposed to a parent, sibling, sports enthusiast, person from a marginalised group, etc.). This may have been a consequence of the environment in which the data were collected (from an education lecturer, discussing experiences of teaching). Therefore, it cannot be assumed that the participants associate completely and independently as a ‘teacher’ first and foremost. Considering this limitation, the researcher acknowledges that some merit may be given to an ethnographic study to triangulate findings from this study. Individual adaptations of teachers to the transition may also provide deeper insight into the extent to which the transition affected the individual teacher within their own circumstances.

Acknowledgements

This study was part of a wider research examining novice teachers’ experiences of transition across teacher education (O’Neill Citation2022) and was supported by the Centre for the Advancement of STEM Teaching and Learning at Dublin City University. This study would also like to acknowledge the contribution of participating teachers without whom this research would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request within the confines of ethical approvals.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Deirdre O’Neill

Deirdre O’Neill is a post-doctoral researcher in the School of Education in UL. Her research interests focus on transition in teacher education, physics teacher education and education outside the classroom. She is currently leading the monitoring and evaluation of the EU-funded OTTER project and implementation of the pilot studies in Ireland.

Eilish McLoughlin

Eilish McLoughlin is an Associate Professor in Physics Education at the School of Physical Sciences in Dublin City University. She is co-founder of the research Centre for the Advancement of STEM Teaching and Learning (CASTeL) and served as Director from 2008 to 2021. Her research interests focus on physics education research at all levels of education. She has led and collaborated in a wide range of research projects focussed on STEM teacher education at national and European level, including ESTABLISH, SAILS, IN-STEM, OSOS, ENERGE 3DIPhE, STAMPEd, RISE and STEM DIGITALIS. She has served as a member of IUPAP C14 Commission for Physics Education 2014–2021 and as Executive Secretary of GIREP (International Research Group on Physics Teaching) Board since 2020.

Notes

1 RPP meetings were regular check-in professional meetings that occurred as part of the design of the wider research project. For the purpose of this study, they were points at which data collection occurred and professional conversations between education researchers and novice teachers occurred. Further detail on their structure and purpose can be found in (O’Neill Citation2022).

2 The indicators outlined in Schlossberg’s model indicated by the pale blue boxes, in , (e.g. period of liminality, groping for new roles, relationships, routines, assumptions, cycle of renewal, hope and spirituality period) were aligned with the themes at each data point to establish the most likely transition to be occurring at that point and time. Year One in the graphic refers to the first year of a two year study.

References

- Angell, Carl, Jim Ryder, and Phil Scott. 2005. “Becoming an Expert Teacher: Novice Physics Teachers’ Development of Conceptual and Pedagogical Knowledge.” Working Document. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Carl-Angell-2/publication/241757089.

- Barclay, Susan R. 2015. “Turning Transition into Triumph: Applying Schlossberg’s Transition Model to Career Transition.” In Exploring New Horizons in Career Counselling, 219–232. Brill.

- Binks, Emily, Dennie L. Smith, Lana J. Smith, and R. Malatesha Joshi. 2009. “Tell Me Your Story: A Reflection Strategy for Preservice Teachers.” Teacher Education Quarterly 36 (4): 141–156. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23479288.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Britt, Patricia M. 1997. “Perceptions of Beginning Teachers: Novice Teachers Reflect upon Their Beginning Experiences.” https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED415218.pdf.

- Brookfield, Stephen. 1998. “Critically Reflective Practice.” Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 18 (4): 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.1340180402.

- Buabeng, Isaac, Lindsey Conner, and David Winter. 2015. “Preparing Physics Teachers for the Classroom: The Role of Initial Teacher Education Providers.” In AERA 2015-Toward Justice: Culture, Language, and Heritage in Education Research and Praxis, 1–15. AERA.

- Bullock, Shawn Michael. 2017. “Understanding Candidates’ Learning Relationships with Their Cooperating Teachers: A Call to Reframe My Pedagogy.” Studying Teacher Education 13 (2): 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2017.1342355.

- Cobb, Donella J. 2022 February. “Metaphorically Drawing the Transition into Teaching: What Early Career Teachers Reveal About Identity, Resilience and Agency.” Teaching and Teacher Education 110: 103598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103598.

- Ellis, Neville John, Dennis Alonzo, and Hoa Thi Mai Nguyen. 2020 June. “Elements of a Quality Pre-Service Teacher Mentor: A Literature Review.” Teaching and Teacher Education 92: 103072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103072.

- Etkina, Eugenia. 2010. “Pedagogical Content Knowledge and Preparation of High School Physics Teachers.” Physical Review Special Topics - Physics Education Research 6 (2): 020110. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTPER.6.020110.

- Ezer, Hanna, Izhak Gilat, and Rachel Sagee. 2010. “Perception of Teacher Education and Professional Identity among Novice Teachers.” European Journal of Teacher Education 33 (4): 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2010.504949.

- Fantilli, Robert D., and Douglas E. McDougall. 2009. “A Study of Novice Teachers: Challenges and Supports in the First Years.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (6): 814–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.021.

- Goodman, Jane, Nancy K. Schlossberg, and Mary L. Anderson. 2006. Counseling Adults in Transition: Linking Practice with Theory. New York: Springer.

- Gray, Ron, Scott McDonald, and David Stroupe. 2022. “What You Find Depends on How You See: Examining Asset and Deficit Perspectives of Preservice Science Teachers’ Knowledge and Learning.” Studies in Science Education 58 (1): 49–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2021.1897932.

- Harland, Tony. 2014. “Learning About Case Study Methodology to Research Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 33 (6): 1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.911253.

- Hopper, Tim. 1999. “The Grid: Reflecting from Preservice Teachers’ Experiences of Being Taught.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 70 (7): 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1999.10605688.

- Larrivee, Barbara. 2000. “Transforming Teaching Practice: Becoming the Critically Reflective Teacher.” Reflective Practice 1 (3): 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/713693162.

- Long, Fiachra, Kathy Hall, Paul Conway, and Rosaleen Murphy. 2012. “Novice Teachers as ‘Invisible’ Learners.” Teachers and Teaching 18 (6): 619–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.746498.

- Loughran, John, Pamela Mulhall, and Amanda Berry. 2004. “In Search of Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science: Developing Ways of Articulating and Documenting Professional Practice.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 41 (4): 370–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20007.

- McLean, Neil, and Linda Price. 2019. “Identity Formation among Novice Academic Teachers – a Longitudinal Study.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (6): 990–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1405254.

- Mercieca, Bernadette Mary. 2018. Companions on the Journey: An Exploration of the Value of Communities of Practice for the Professional Learning of Early Career Secondary Teachers in Australia. Queensland: University of Southern Queensland. https://doi.org/10.26192/5c0a026ef0cd4.

- Merriam, Sharan B., and Elizabeth J. Tisdell. 2016. “Qualitative Research : A Guide to Design and Implementation.” 4th ed. In The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, a Wiley Brand. 368 pages

- Moon, Jennifer A. 2004. A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning: Theory and Practice. New York: Psychology Press.

- Mulholland, Judith, and John Wallace. 2003. “Crossing Borders: Learning and Teaching Primary Science in the Pre-Service to in-Service Transition.” International Journal of Science Education 25 (7): 879–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690305029.

- Nguyen, Minh Hue. 2017. “Negotiating Contradictions in Developing Teacher Identity During the EAL Practicum in Australia.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 45 (4): 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2017.1295132.

- O’Neill, Deirdre. 2022. Insights Into the Professional Learning of Physics Teachers: An Examination of Novice Teachers’ Experiences of Transition. Dublin: Dublin City University.

- Penuel, William R, and Daniel J Gallagher. 2017. Creating Research Practice Partnerships in Education. Cambridge: ERIC.

- Pietsch, Marilyn, and John Williamson. 2010. “‘Getting the Pieces Together’: Negotiating the Transition from Pre-Service to in-Service Teacher.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 38 (4): 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.515942.

- Rieg, Sue A., Kelli R. Paquette, and Yijie Chen. 2007. “Coping with Stress: An Investigation of Novice Teachers’ Stressors in the Elementary Classroom.” Education 128 (2).

- Robinson, Oliver C. 2011. “Relational Analysis: An Add-On Technique for Aiding Data Integration in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 8 (2): 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2011.572745.

- Romero-Ariza, Marta, Antonio Quesada, Ana Maria Abril, Peter Sorensen, and Mary Colette Oliver. 2020. “Highly Recommended and Poorly Used: English and Spanish Science Teachers’ Views of Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) and Its Enactment.” Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 16 (1).

- Schlossberg, Nancy K. 1981. “A Model for Analyzing Human Adaptation to Transition.” The Counseling Psychologist 9 (2): 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/001100008100900202.

- Stokking, Karel, Frieda Leenders, Jan De Jong, and Jan Van Tartwijk. 2003. “From Student to Teacher: Reducing Practice Shock and Early Dropout in the Teaching Profession.” European Journal of Teacher Education 26 (3): 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261976032000128175.

- Tammets, Kairit, Kai Pata, and Eve Eisenschmidt. 2019. “Novice Teachers’ Learning and Knowledge Building During the Induction Programme.” European Journal of Teacher Education 42 (1): 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2018.1523389.

- Thomas, Gary. 2011. “The Case: Generalisation, Theory and Phronesis in Case Study.” Oxford Review of Education 37 (1): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2010.521622.

- Timperley, Helen, and Adrienne Alton-Lee. 2008. “Reframing Teacher Professional Learning: An Alternative Policy Approach to Strengthening Valued Outcomes for Diverse Learners.” Review of Research in Education 32 (1): 328–369. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X07308968.

- Tynjala, Paivi, and Hannu L. T. Heikkinen. 2011. “Beginning Teachers’ Transition from Pre-Service Education to Working Life.” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 14 (1): 11–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-011-0175-6.

- Wall, Peter, Catherine Fetherston, and Caroline Browne. 2018. “Understanding the Enrolled Nurse to Registered Nurse Journey Through a Model Adapted from Schlossberg’s Transition Theory” Nurse Education Today 67: 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.04.017.

- Wilson, Suzanne, Heidi Schweingruber, and Natalie Nielsen. 2016. Science Teachers’ Learning: Enhancing Opportunities, Creating Supportive Contexts. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21836.

- Zhukova, Olena. 2018. “Novice Teachers’ Concerns, Early Professional Experiences and Development: Implications for Theory and Practice.” Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education 9 (1): 100–114. https://doi.org/10.2478/dcse-2018-0008.

Appendix