ABSTRACT

This paper examines attitudes to classism in Irish education using a thematic analysis of social media conversations about social class between 2018 and 2022. Previous research indicates that Irish education systems are designed by and favour the dominant and ruling classes. However, few studies use the voice of the lived experience to explore the phenomenon. This article investigates Irish people’s communication of class inequalities in education via the social media platform Twitter (X). Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis was employed to analyse and group the Tweets, with Dean’s framework on communicative capitalism to guide the findings. This study indicates that social media has become a legitimate platform to challenge hegemony in education by creating online communities or collective identities in struggles against social inequalities in Ireland. Findings reveal that classism continues to prevail in Irish education, with working-class Tweets on the lived experiences of discrimination providing novel insights on emerging themes such as elitism, inequality of access and symbolic violence. Future research in this area needs to focus on the effects of social class on educational attainment, access, and participation in Irish settings. In particular, examining weaknesses in current structures to support working-class students, and possible grassroot interventions and policies to mitigate the impacts of social class on education.

Introduction

It is apparent from Twitter narratives that class continues to have a lasting effect on education and outcomes due to continued and deep-rooted inequalities in our country. Bourdieu’s multi-layered theory of class posits that it is economic, social, cultural, and emotional capital which reproduce class by moulding and limiting social networks, educational opportunities, and aspirations (Reay Citation2006). This paper examines the interactional conversations on Twitter surrounding social class issues in Ireland. The research is based on multi-participant and asynchronous interactions on the social media platform and aims to provide new insights into socio-cultural discourses produced around class, as experienced by Irish people between 2018 and 2022. The paper seeks to capture the conversations that attempt to legitimise these class issues, moreover, exploring the class impacts on the Irish education system and how individuals choose social media to challenge Irish political ideologies and the social constructs of class hierarchies.

The Twitter feeds are analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) thematic analysis and focus on how Irish social class divisions are discursively created and perceived by a wide range of people. This is particularly evident amongst the working-class sector, where voices are too often powerless due to marginalisation in the mainstream media, indicating that social media has become a platform to mitigate some of the class power struggles. It offers people from marginalised backgrounds a voice and representation of their own narrative in a new and unedited manner, where they can express their frustrations, lack of power, and experiences of class discrimination. Social media is a form of self-representation on class issues which Bourdieu (Citation1984) describes as an integral part of class identity. Using this form of self-representation, the study answers three research questions through thematic analysis:

What are the leading themes that Twitter users emphasise on social class inequalities in the Irish education system?

How do the Tweets articulate and call on users to empathise with the issues?

How can we understand expressions on social media as an attempt to highlight social injustices in Irish education?

Social class in Ireland

Social class represents an enduring focus of sociological inquiry. It stratifies people into hierarchical social categories and is typically based on the constructs of resources, authority, and expertise which relate to a person’s position in relation to means of production (Giddens Citation1971). Social class is linked to wealth which is seen as an index of occupation, income, and status, i.e. the level of esteem an individual can attract. It relates to control, power, and political effectiveness (Entwhistle Citation1978). Contrastingly, for Bourdieu (Citation1984) social class is understood to represent positions in social space and how people occupy this space is determined by their economic position within a system of production Furthermore, governed by their possession of different types of capital (Bourdieu Citation1986).

Historically, Ireland does not have a strongly defined social class hierarchy, and the term ‘social class’ is rarely used. Muntaner, Lynch, and Oates (Citation2020) argue that social class is a taboo subject in Ireland that is kept hidden, and if discussed, it is in euphemisms that hide it’s the reality of its existence. This is compared to countries like the UK and mainland Europe, where class inequalities are an integral part of political debate. ‘When people talk about class-based injustices, they are accused of making political debates “ideological”’ (Muntaner, Lynch, and Oates Citation2020, 3). Senator Lynn Ruane (Citation2013) states that despite statistics pointing at social class issues in the country, as a society there is a failure to recognise the role class plays in accessing adequate healthcare, education and general life prospects. Therefore, despite a lack of obvious delineation or recognition of class structures, Ireland appears as divided as the UK and mainland Europe.

In this social media research, one of the aims was to discover how class-conscious the Irish are, by tracing Twitter conversations about class constructs. Interestingly reviews of the data show that conversations do not openly discuss class systems within the country. However, when Ireland is described as ‘classless’ on Twitter, individuals are quick to anger and articulate that their life experiences in this country would tell a very different tale. The reactions of working-class Irish people to an ideology of a classless country are emotive and almost Dickensian in description. Gillmor (Citation2006) states that social media offers people an opportunity to share mostly unfiltered opinions and allows a greater variety of ideas and opinions to be available in the public sphere, thus providing a type of digital ethnography to produce rich descriptive data.

Social media and Twitter

According to Hogan and Quan-Haase (Citation2010) social media are digital applications that allow multi-person interaction and engagements. Twitter (now X) is described as the fastest and most critical tool for reaching and mobilising people, for gathering data and responding to public reactions (Parker Citation2012). Twitter/X has 1.5 million subscribers in Ireland (CSO Citation2020), equating to nearly 30% of our population, which indicates its far-reaching potential not only nationally but internationally. Larsson and Moe (Citation2014) noted that unlike other social media platforms which can be dominated by socio-economic elites, Twitter is a platform on which individuals from any status can get their tweets shared and liked as much as elites. Hastags make Tweets searchable and were therefore used to find relevant relatable discourses on social class. Zappavigna (Citation2011) describes hashtags as a function of flagging a subject and as a tool that connects users who share similar emotions or stories.

Theoretical framework

Bouvier (Citation2015) purports that social media provides a site of fundamental shifts in communicative practices, genres and modalities. She proposes that in studying social media and discourse, it needs to engage with the wider issue of power, ‘the nature of the wider power relations that they inhabit and how these may be influenced by shifts in the communications landscape’ (2). Therefore, the connection between social media as a source of empowerment in social class discussions needs to be critically examined.

To achieve the examination of the Tweets in an analytical way, Dean’s critical media theory is employed as a framework of inquiry into these media conversations and observations. Dean provides a critical approach to digital media, examining the political implications of networked communication, which she terms as communicative capitalism and describes as:

A form of capitalism in which … ideals of access, inclusion, discussion and participation are realised through expansions, intensifications and interconnections of global telecommunications. (Citation2010, 4)

There is intersectionality between the use of communicative capitalism through social media and social class issues. This capitalism provides voice and space for under class and working class, who previously did not have collective strength and power in the mainstream media. From a working-class perspective, this potential to share content on class issues and discriminations is thus extremely important in bringing underrepresented issues to the fore. The sharing of data through likes, shares or retweets can help gather momentum on social class struggles and their legitimation amongst Irish society. It creates an antithesis to mainstream media which is dominated by middle- and upper-class rhetoric and cultures. According to Downey, Titley, and Toynbee (Citation2014) the mainstream media is lending to the legitimisation of socio-economic stratifications that form the very foundation of a class society. Jakobssen, Lindell, and Stiernstedt (Citation2021) find that the issue of class is invisible, downplayed, or silenced in mainstream media and journalism, which undoubtedly adds to the confusion surrounding the topic, and a person’s reluctance to use categories of class to understand their own living conditions.

Furthermore, Dean offers a framework to understand the reasoning behind the rise in communicative capitalism and that is the collapse of symbolic efficiency, which is a societal rebellion against macro institutions and governance. She states that correlative to the change in communication is a change in subjectivity, ‘formerly powerful markers of symbolic identity no longer organise action. As symbolic figures for politics, they have been critiqued, complicated, and pluralized’ (Citation2014, 4). Zizek (Citation1997) describes the decline in symbolic efficiency as a fading of a central force or institutional body of knowledge, scepticism has created despondency in governing bodies who in the past enforced ideas, values and identities, such as governments or religious organisations. This waning symbolic efficiency leaves a gap which social media can fill, individuals are seeking truths and values from more local sources, beliefs and opinions, power can be achieved in the sharing and reproduction of ideas, and socio-political ideologies, and campaigns can build momentum and strength. Bouvier (Citation2015) proposes that this demise of central authority allows for the celebration of ‘more localised identities, ideas and values as regards how esoteric they are (4). Turner (Citation2010) claims that social media has taken a ‘demotic turn’ where ordinary people have become a more visible and obvious part of media content, indicating that this allows those lacking in power in the traditional sense, an outlet to voice their opinions and find their identities. Social media is now blended into the fabric of daily life, furnishing new avenues for communication, new methods of maintaining, creating, or imagining cultural communities and identities and combining locally nuanced ideas, values and identities (Shi-xu Citation2014).

In summary, the use of Dean’s communicative capital and lack of symbolic efficiency is a theoretical frame for the examination of Tweets, assessing individual’s approaches to challenging central sources of power on class issues and middle-class ideologies that serve the dominant classes. By engaging in the empowering effect of the circulation of their content through likes, comments and retweets, working-class individuals are gifted the opportunity of a global platform in which they can hope for awareness and legitimation of their message through circulation.

Methods

Data collection

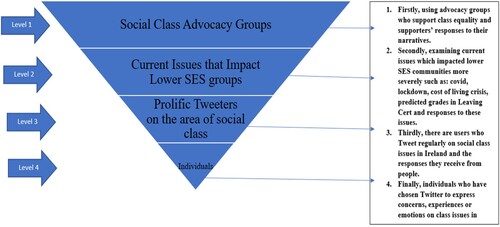

The Twitter search process is shown in .

The research takes data drawn from Twitter as its focus. The paper analyses tweets from 2018 to 2022, the conversations were gathered from public Irish based accounts using the handles or hashtags of social class, class mobility, working class, cultural capital, social capital, classless Ireland, social class Ireland, Irish class systems, class and education, class and identity (see for search order). These topics were gleaned from the author’s literature review of PhD research on social class mobility in Ireland. This selection rendered a total of nearly 1000 tweets which is similar to data recorded in other published studies. Tweets included for analysis were generated by almost 400 individual Twitter users, some accounts tweeted several messages on the same topic. Tweets were selected using the inclusion criteria that they must be (1) Irish accounts, (2) relating to class-based topics only, and (3) within the designated timeframes. This resulted in 620 tweets that fulfil the purpose of understanding people’s identity in class, the language used to legitimate class, and finally the emotions and experiences of social class in Ireland.

Data analysis

All 620 selected tweets were then grouped thematically in line with Baxter’s (Citation2011) approach. Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis framework was then used to analyse the Tweets. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) describe this analysis as being ‘driven by the theoretical interest in the area’ (84). The first analysis focused on forming latent themes, the identification of underlying ideas and concepts through interpretative work (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This was followed by grouping commonalities to form initial codes. Charmaz (Citation2014) advises that initial codes provide the researcher with tools for interrogating and sorting documents, ‘it shapes the analytic frame from which you build the analysis’ (113). This in-depth coding ensures deep engagement and continuous interaction with the data, using the recording of memos as an integral part of the process from the beginning. According to Charmaz (Citation2014) this provides the researcher with ‘space to become actively engaged in the materials, to develop ideas and engage in critical reflexivity’ (163).

Once all initial codes were extracted, they were colour coded according to repetition or points of interest related to the research topic. They were then gathered into a table according to colour codes, analysed and provided with an in-vivo code, which is a term to capture the meaning of the grouped initial codes (Charmaz Citation2006). These grouped codes were then reviewed further to examine connectivity and relationships to the research, the most prevalent were chosen as focused codes for potential themes, others at this stage were discarded. ‘Attending to focused coding through making informed choices from your initial codes can give you the skeleton of your analysis’ (Charmaz Citation2014, 141). Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) emphasise that at this stage of analysis you should have an idea of how themes fit together and the overall story they tell.

As the table is continuously edited further memos were developed as dominant themes became apparent and distinct, with a cognisance of the research aims. The most relevant focused themes were extracted from the table and drawn into a thematic table to examine further connectivity while continuing reflexive memoing to stay in touch with the data. Saldaña (Citation2016) purports that codes should be used as a prompt to evoke reflection on deeper and complex meanings and connections. When all comments were grouped in their focused themes, it was observed that there were five categories of recurring themes in the discourse that related to social class in Ireland. The focused themes include:

Challenging Power and Political Ideologies – The Lack of Symbolic Efficiency

The Issue of Class in Irish Education –

Reproducing Inequalities

Space and Voice of the Working Class in Academia

Social and Economic Capital of Students in Education

Role of Teachers in Class Reproduction

Accents in Academia

Class Divides in Ireland and Social Class Mobility

Classism – the more accepted discrimination

Legitimisation of Social Class Hierarchies in Ireland through Social Media.

Reproducing Inequalities in Higher Education – Capitals, Symbolic Violence and Accents

Reproducing Inequalities in Second Level and

The Role of Educators in Class Reproduction.

Findings and discussions

Over 20% of Tweets collected related to people’s encounters or emotions on class and the Irish education system. The discussions on the lived experiences of classism in both second and third levels are very rich and create a tapestry of information surrounding the relationship between class and education. Third-level academia produces more discussions than the other education levels, with narratives reporting higher barriers of access, and being inherently upper/middle class in culture. According to the Higher Education Authority (HEA Citation2019), access to the most selective higher education courses is heavily dominated by those from the most affluent (white Irish) families. These tweets reflect that a sizeable percentage of students when entering third level from working-class backgrounds, have the surprising realisation of the level of class divides that exist in the country. Previously sheltered at lower levels of education on class divides, third-level exposes some individuals for the first time to a place in society where socio-economic backgrounds are blended in high proportions on one campus. Social, cultural, and economic capital differences are brought to the forefront.

Reproducing inequalities in third level – capitals, symbolic violence, and accents

In relation to third-level institutions individuals’ Tweets predominantly narrated memories and experiences of exclusion and alienation due to their socio-economic background. Elitism is reported as being celebrated in certain institutions and without the correct social networks, college life can be a difficult path to navigate. Bathmaker, Ingram, and Waller (Citation2013) purport that middle-class university students use their capitals to maintain their advantages in college through the ‘acquisition, development, and mobilisation of their cultural, social and economic resources’ (94). However, working-class individuals struggle to compete when their capitals and resources are limited.

‘Life’s most humiliating experiences can take place at university; classism runs through it.’

‘Third level institutions have become a manifestation of classism.’

‘Education policies are reproducing and keeping educational disparities.’

‘Colleges and universities need to tackle socio-economic diversity.’

‘Academia is not class friendly.’

This concludes that the working-class struggle to find space and voice within middle-class dominated education systems, who serve to respect and value middle-class capital and voice.

The idea of working-class space and voice in education, especially third level, resulted in very interesting Tweets on individual’s experience of trying to navigate their space in academia. Discussions proposed that in lieu of the elites and privileged academics speaking for and representing the working class, could they step back and allow working-class students and academics the space and voice to represent themselves?

‘Wouldn’t it be great if we reversed the narrative and asked the more privileged to speak less and relinquish the space they already have, makes more sense than fighting for space that working class do not and may never have.’

‘Do elites ever step back in academia and allow marginalised people take promotions, chair a meeting, sit on a panel or allow them to rise and occupy these spaces.’

‘Working class are often the subject of analysis, the academic bourgeoise appear threatened when they realise that we working class are more than capable to occupy this intellectual space.’

‘Working class students and academics often live at the literal and metaphorical distance from cultural and social forms of capital. Yet they bring their own forms of capital to campuses. Higher education institutions need to recognise their capital is valuable.’

‘Societal and institutional production and reproduction for working class academics.’

‘My ability to speak my mind, to fight the system, to see the gaps in the structures were taught to me by the poverty I lived through. And by being given the opportunity to use these skills in an academic sense is imperative.’

‘The wealth experience of the working class has only the potential to enhance colleges and universities, their staff and the world, if given the right time, chances and support.’

‘College campuses need to be more open to working class, why do we need to conform, why can’t campuses open up their systems to fit with us and not vice versa.’

‘Third level institutions need to be more working class friendly, a shift in mindset from disadvantaged students needing to be college ready to campuses needing to be more student friendly.’

Social and economic capital of students

This theme explores micro-class differentiations, rather than discussing the macro or institutional level of symbolic violence, these tweets are grouped based on individuals’ experience of class gaps amongst themselves and their peers. Third-level institutions house a wider range of socio-economic origins compared to primary or secondary levels, and for a percentage of students it is the first time that they get to work alongside and socialise with individuals outside of their own class. Reay (Citation2013) believes this gap is felt in college more because children and young people from different socio-economic backgrounds are increasingly educated apart rather than together in schools that are predominantly middle or working class. The biggest gaps felt by working class are economic and social capital, Major and Machin (Citation2018) claim that these middle-class capitals acquired in life are very marketable in higher education and careers and can aid social mobility more than education itself. They state that these capitals are generationally exchanged through family, community, and peer-group socialisation. In middle-class dominant settings like colleges, this can leave working-class students feeling isolated and unrelatable. ‘When attempting to express our thoughts and opinions across vast gulfs in social and cultural experiences, nuance gets lost in translation’ (McGarvey Citation2017, 125).

‘In a class of thirty in college I was the only one with an accent and having to work part-time to support myself.’

‘In college my middle-class friends were always going out for lunch, some of their parents owned the properties they lived in near college, and they were always wearing labels. I on the other hand brought my lunch to college, went out less and had to work a lot harder to support myself.’

‘When I went to university a lot if my peers could not grasp how much I had to work to support myself, I felt judged but realistically I did not have financial parental supports, my parents were barely surviving.’

‘I was asked in a Dublin University how I managed to get in there when I told a peer where I was from.’

Accents in academia

According to conversations on Twitter, accents are the strongest class characteristic and identifier that can separate and isolate working-class students and academics from their more privileged peers. Individuals discuss using digital technology like Google and YouTube to learn how to pronounce certain words prior to speaking with middle- and upper-class peers and teachers. In doing this, they can avoid discrimination and judgement by softening or altering their accents as they feel it links them to their address and social origin. A study conducted by Keane (Citation2023) revealed that the classed sign-equipment predominantly used by individuals in her research included their physical appearance in terms of dress and accessories, but moreover, their accent and ways of speaking.

‘On my first day of lectures I was called a scumbag for nothing more than my accent.’

‘Sometimes the night before a presentation or event I sit on YouTube listening to the pronunciation of certain words to avoid judgement on my accent.’

‘I was judged and asked how I ever made it to college by a person based only on my accent.’

‘Being asked to repeat something when you know the person heard you, but you have mispronounced it in your common accent. I see it, I feel it and it makes me feel like shit.’

‘For all our progress on diversity and inclusion in education, accents can still be a huge barrier in classless Ireland.’

These Twitter conversations expose the pressures people feel to change accents to be accepted professionally and academically, with people expressing a lack of power and space because they are speaking less to avoid judgement, resulting losing their voice and face changing of identity and erasing elements of their past. Gamsu (Citation2019) states that accents are tied into uneven regional geographies of economic and cultural power. ‘The associations between intelligence and forms of middle-class and elite speech and accent are deeply woven into class structures’ (Guardian Newspaper Citation2019).

Reproducing inequalities – second level

Cahill and O’Sullivan (Citation2022) report that disadvantaged schools get the same level of public spending as private fee-paying schools, the latter having access to large financial funds, grinds culture and ‘any other means that can be employed to cultivate success within a system that facilitates such inequalities of outcome’ (475). The pandemic drew attention to certain facets of class differences between fee-paying and educationally disadvantaged schools. In particular, a dominant example of unequal practice was the predictive grades for the 2020 Leaving Certificate, a system put in place by government to replace the traditional Leaving Certificate points system, which could not run due to the pandemic and school closures. The education policy for these grades can be summarised as follows; in lieu of sitting exams, the 60,000 plus students would be assigned a grade in each of their subjects of study based on four sources of data:

Estimated marks and rankings from teachers

Junior Cycle exam performance

Historical national distribution of students’ results subject by subject (bell curve system used in all years for standardisation)

Historical school data based on past Leaving Cert exam performance in schools across three previous years (DES Citation2020).

A major pitfall with predicted grades was that a high achieving student in a designated disadvantaged school now faced a situation where their results could be unfairly reduced due to their own socio-economic background while meritocratic ideology was ignored. In reverse, a privileged student in an elite school could potentially earn more points based on their socio-economic background rather than merit. This approach further compounded the inequalities of the Leaving Cert system.

At this time in 2020, Tweets were displaying aggrievance with predictive grades, because upper-class students with access to grinds, lower teacher–pupil ratios and result-driven structures held unfair advantage over students in educationally disadvantaged schools. These elite schools are also heavily supported by parents with excellent sources of capital both economically, culturally and socially.

‘Difference in fee paying schools and public schools highlight the two-tiered systems during Leaving Certificate grade predictions.’

‘These Leaving Certificate predicted grades highlight the need for lower class sizes in the public schools when comparing to private fee-paying institutions.’

‘Governments should not be providing capitation for elite schools; it furthers the divide creating a corrosive two-tiered system.’

The role of educators in reproducing class inequalities

Research commonly claims that teachers’ perceptions are often not neutral, but class related (Reay Citation2006; McGillicuddy and Devine Citation2018) and those practices such as academic selection position learners within a hierarchy. The research of Dunne and Gazeley (Citation2008) supports this, when their findings concluded that there were differences in the way that teachers ‘constructed the underachievement of middle-class and working-class pupils, and these prompted different strategies for addressing it’ (461). They continue that teachers’ expectations on pupil’s attainment and achievements were influenced by not only the pupil but the pupil’s home, and underachievement was more readily accepted by students perceived to be working class compared to middle-class learners.

In this theme, individuals discuss their experiences of discrimination and prejudices based on their social class and socio-economic backgrounds from teachers and lecturers throughout their educational journeys. Teaching skills that allow empathy to encourage students with disadvantage to develop aspirations, to create an accepting space that is respectful of different cultural backgrounds needs to be central in both initial teacher education policy and practice. Therefore, creating policy at both national and local level that seeks to mitigate these micro-social processes in school settings and their personnel. Irish student’s experiences of classism with educators in schools are still evident in their sharing of their stories on educational experiences on Twitter.

‘Education reproduces class inequality and teachers need to be better trained in this area for empathy and understanding.’

‘Teachers lack awareness on class issues, colleges and schools need to train staff in this area.’

‘In college my lecturer was encouraging the class to pursue postgraduate courses, completely oblivious to the fact that this was way beyond some of our reaches socially and economically.’

‘A teacher went around the class and told us all one by one at 14 years of age what we would go on to achieve. The divide in her estimation was less on academic ability but more on parental income and address.’

Conclusions

This study has aimed to analyse the voicing and diversity of attitudes on Twitter to social class and education, and how class can impact individual’s educational journey. Dean’s theory has been used as a lens to examine the Tweets and understand how communicative capital provides individuals a source of media attention that mobilises support for collective actions. Therefore, working-class individuals have gained access to a media source that provides agency and advocacy to challenge hegemony in macrosystems like education. Witschge (Citation2008) purports that social media outlets like Twitter can provide grassroots, disadvantaged, and powerless people with a channel to access information and voice their issues to create social justice movements. Furthermore, Adams and Roscigno (Citation2005) propose that public forums can create collective identity for those who share similar ideologies but were previously disconnected, thus, empowering the voiceless and building communities through the sharing of experiences, opinions and values. Dean (Citation2014) proposes that the power in these forms of communication is not in the content but in the momentum the message can build through likes, shares and comments, ‘what matters is not what was said but rather that something was said’ (6)

It is evident from the Twitter (X) data collected on the last four years, classism continues to prevail in education systems, with working-class students’ Tweets on lived experiences providing novel insights into their journey through education. This research aimed to delineate salient themes that Twitter users encapsulate in their writings on experiences of social class-related incidences in both their past and present in Ireland. As part of larger study on social class issues in this country, education had the strongest and most recurring conversations on the media site with five leading themes emerging from the data analysis. Revealing issues on a macro level in education such as elitism, inequality of access, continued barriers to participation and progression, and symbolic violence through limited space and voice for working-class students. On a micro level the themes reveal working-class student’s isolation, discrimination, and an inherent deficit in social, cultural and economic capitals. The Tweets call on readers to empathise with these issues, by acknowledging the value the working-class culture can add to educational institutions, to avoid discriminating students based on class identifiers like accents and address, and allow meaningful space and voice for all students within education in Ireland.

This type of research highlights the importance of social media in providing unique insights into the intensity of social class issues in Ireland, by furnishing the reader with a bird's eye view of individuals’ emotions and lived experiences within the Irish education system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Helen Lowe

Helen Lowe is a doctoral candidate with a background in post-primary education. An interest in equity of opportunity, social class mobility, social and educational disadvantage, inclusive practices for students with additional and special educational needs, social class structures, socio-cultural understandings of learning, identity, and assessment.

References

- Adams, J., and V. J. Roscigno. 2005. “White Supremacists, Oppositional Culture and the World Wide Web.” Social Forces 84 (2): 759–778. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0001

- Ashley, L., J. Duberley, H. Sommerland, and D. Scholarios. 2015. A Qualitative Evaluation of Non-educational Barriers to the Elite Professions. London: Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission.

- Bathmaker, A., N. Ingram, and R. Waller. 2013. “Higher Education, Social Class and the Mobilisation of Capitals: Recognising and Playing the Game.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (5–6): 723–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.816041

- Baxter, L. A. 2011. Voicing Relationships: A Dialogic Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 81–92. New York: Greenwood.

- Bouvier, G. 2015. “What is a Discourse Approach to Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Other Social Media: Connecting with Other Academic Fields?” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 10 (2): 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2015.1042381

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cahill, K., & D. O’Sullivan. 2022. “Making a Difference in Educational Inequality: Reflections from Research and Practice.” Irish Educational Studies 41 (3): 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2085763.

- Central Statistics Office. 2020. Vital Statistics Yearly Summary, 2020.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Connolly, C. 2021. “Recognising Misrecognition: Challenging the Reproduction of Inequality and Subverting Doxastic Thinking in Initial Teacher Education.” International Journal of Educational Research 109: 101–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101834

- Crew, T. 2020. Higher Education and Working-Class Academics Precarity and Diversity in Academia. Cham: Palgrave Pivot.

- Dean, J. 2009. Democracy and Other Neoliberal Fantasies: Communicative Capitalism & Left Politics. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822390923.

- Dean, J. 2010. Blog Theory. London: Polity.

- Dean, J. 2014. “Communicative Capitalism and Class Struggle.” Spheres: Journal for Digital Cultures 1: 1–16.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2020. Implementation of Calculated Grades Model For Leaving Certificate 2020 – Guide for Schools on Providing Estimated Percentage Marks and Class Rank Orderings. Dublin: Government Publications. Accessed March 19, 2023. https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/74604/d9e27dc5986e49a5a1b24623e77308d3.pdf#page=null.

- Downey, J., G. Titley, and J. Toynbee. 2014. “Ideology Critique: The Challenge for Media Studies.” Media, Culture & Society 36 (6): 878–887. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443714536113.

- Dunne, M., and L. Gazeley. 2008. “Teachers, Social Class and Underachievement.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 29 (5): 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690802263627

- Ellis, S., I. Thompson, J. Mcnicholl, and J. Thomson. 2016. “Student Teachers’ Perceptions of the Effects of Poverty on Learners’ Educational Attainment and Well-Being: Perspectives from England and Scotland.” Journal of Education for Teaching 42: 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2016.1215542.

- Entwhistle, N. J. 1978. “Educational Research in Classrooms and Schools,” by Louis Cohen (Book Review). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Equality Laws in Ireland. 2023. “Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission.” Accessed September 14, 2023. www.ihrec.ie/your-rights/equality-laws-ireland/.

- Gamsu, S. quoted in: D. Lavelle. 2019. “The Rise of ‘Accent Softening’: Why More and More People are Changing Their Voices.” The Guardian Newspaper, 20 Mar. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/mar/20/ugly-rise-accent-softening-people-changing-their-voices.

- Giddens, A. 1971. Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gillmor, D. 2006. How to Use Flickr: The Digital Photography Revolution. Boston, MA: Thomson Course Technology.

- Higher Education Report. 2019. Annual Report. Dublin: HEA.

- Hogan, B., and A. Quan-Haase. 2010. “Persistence and Change in Social Media.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30 (5): 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610380012

- Jakobsson, P., J. Lindell, and F. Stiernstedt. 2021. “Introduction: Class in/and the media: On the Importance of Class in Media and Communication Studies.” Nordicom Review 42: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2021-0023.

- Keane, E. 2023. “Chameleoning to Fit in? Working Class Student Teachers in Ireland Performing Differential Social Class Identities in Their Placement Schools.” Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2023.2185592.

- Larsson, A. O., and H. Moe. 2014. “Triumph of the Underdogs? Comparing Twitter Use by Political Actors During Two Norwegian Election Campaigns.” SAGE Open 4 (4): 215824401455901. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014559015

- Levon, E., D. Sharma, and C. Ilbury. 2022. Speaking Up: Accents and Social Mobility. London: Sutton Trust.

- Major, L. E., and S. Machin. 2018. Social Mobility and Its Enemies. London: Pelican Books.

- McCoy, S., D. Byrne, P. O. Connell, E. Kelly, and C. Doherty. 2009. Hidden Disadvantage? A Study on the Low Participation in Higher Education by the Non-Manual Group. Dublin: Higher Education Authority.

- McGarvey, D. 2017. Poverty Safari: Understanding the Anger of Britain’s Underclass. Edinburgh: Luath Press.

- Mcgillicuddy, D., and D. Devine. 2018. ““Turned Off” or “Ready to Fly” - Ability Grouping as an Act of Symbolic Violence in Primary School.” Teaching and Teacher Education 70: 88–990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.11.008.

- McKenzie, L. 2021. “Class Cleansing: Grieving for London.” International Working-Class Academics Conference, Blackburn, UK, July.

- Muntaner, C., J. Lynch, and G. L. Oates. 2020. “The Social Class Determinants of Income Inequality and Social Cohesion.” In The Political Economy of Social Inequalities, edited by International Journal of Health Services, 367–399. London: Routledge.

- Parker, R. 2012. “Social and Anti Social Media.” New York Times, 15 November, Social and Anti-Social Media - The New York Times (nytimes.com). Accessed March 31, 2022.

- Reay, D. 2006. “The Zombie Stalking English Schools: Social Class and Educational Inequality.” British Journal of Educational Studies 54 (3): 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00351.x

- Reay, Diane. 2013. “Social Mobility, a Panacea for Austere Times.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.816035.

- Ruane, L. 2013. “The Devastating Impact of Social Class is not an Abstract Concept to Hundreds of Thousands on this Island.” The Irish Journal, 12 Aug. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://www.thejournal.ie/readme/lynn-ruane-opinion-social-class-opinion-4169652-Aug2018/.

- Saldaña, J. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Shi-xu. 2014. Chinese Discourse Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Turner, G. 2010. Ordinary People and the Media: The Demotic Turn. London: Sage.

- Veenstra, A. S. 2007. "Blogger/Reader Interaction: How Motivations Impact Pathways to Political Interest." Annual Conference of the Midwest Association for Public Opinion Research.

- Witschge, T. 2008. “Examining Online Discourse in Context: A Mixed Method Approach.” Javnost – The Public 15 (2): 75–92.

- Zappavigna, M. 2011. Discourse of Twitter and Social Media. 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury.

- Zizek, S. 1997. “The Big Other Doesn’t Exist.” Journal of European Psychoanalysis 5: 1–9.