ABSTRACT

Aim

Initially, this paper delves into the connection between Irish society and Project-Based Learning (PBL) and curriculum, exploring how this connection has influenced the evolution of Digital Spaces (DS). It positions the origins of the Transition Year Program (TYP) in Ireland within the context of societal and political changes that are relevant to the education field. Lastly, the focus shifts to a particular change, the integration of PBL, curriculum, and DS within the framework of the TYP. No review of research on the TYP in Ireland is currently available in relation to PBL in DS and this is timely given the policy context's recent focus on the digital world and the development of students’ digital competence.

Research Question

How are PBL Environments understood in the context of the TYP?

Approach

This paper follows the steps of a literature review and thematic synthesis.

Findings

Themes are identified and described, summarising the most current TYP research in Ireland. Sufficient time must be allocated for the coordination of activities and the facilitation of collaboration among teachers to foster participation in DS. Moreover, the TYP should incorporate structured opportunities for students to gain exposure to PBL in DS.

Introduction

This narrative literature review examines three interconnected topics. Initially, it delves into the connection between Constructionism and Project Based Learning (PBL), exploring how this connection has influenced education. Next, it positions the origins of the Transition Year Program (TYP) in Ireland within the context of societal and political changes that are relevant to the education field. Lastly, the focus shifts to a particular change, the integration of PBL and the evolution of Digital Spaces (DS) within the framework of the TYP.

PBL in the TYP can be an effective way to develop digital competence among students. By engaging in individual projects that require the use of digital tools and technologies, students can enhance their skills and understanding in various aspects of digital literacy. Constructionism is an approach towards PBL and DS appearing in many different settings, but how are these places understood in the context of the Irish TYP? This narrative literature review explores Irish education identification with PBL and curriculum and addresses how the TYP is found within this context. It is necessary to briefly explain the term of constructionism before progressing further. The term begins to make sense when distinguished from PBL.

Evolving digital spaces

Bough and Martinez Sainz (Citation2022, 12) focus on the evolving digital spaces in education in Ireland and affirm that ‘the social construction of DS needs greater engagement from key stakeholders such as teachers and learners in its development and review to accordingly prepare learners for the future.’ Ferrari (Citation2012) defined digital competence as: ‘the set of knowledge, skills, attitudes, abilities, strategies and awareness that are required when using ICT [information and communication technologies] and digital media to perform tasks; solve problems; communicate; manage information; collaborate; create and share content; and build knowledge effectively, efficiently, appropriately, critically, creatively, autonomously, flexibly, ethically, reflectively for work, leisure, participation, learning and socialising’ (30).

The European Union (EU) laid out ambitious goals in its ‘Digital Education Action Plan’ (EC Citation2020), seeking to guide governments and policy makers in nurturing digital competence among learners. However, the unprecedented arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic brought both opportunities and challenges for Irish second level educators and students alike (Bray et al. Citation2021). As educators embraced digital platforms and virtual environments for learning, communication, and collaboration (Connolly et al., Citation2022), learners also encountered vulnerabilities such as cyberbullying, harassment, and exposure to unsafe content (Marcus-Quinn and Hourigan Citation2022).

In Ireland, the ‘Digital Strategy for Schools to 2027′ envisioned a transformative educational landscape, fostering competent, critically engaged, and active learners who could thrive in the digital realm as global citizens (DoE Citation2022). Echoing this vision, the Transition Year Programme (TYP) aimed to infuse information technology throughout the curriculum (DES Citation1993), propelling students towards a technology-driven future. However, as the digital revolution continued to reshape education (O’Regan, Brady, and Connolly Citation2021; Citation2022; O’Sullivan et al. Citation2023; Citation2021), the practical implementation and impact of digital competence in the TYP remained largely unexplored.

Marcus-Quinn and Hourigan (Citation2022) extensively examine the emerging digital spaces in education in Ireland and the tiers of teaching and learning that are influenced by private companies, industry and operations that have their own agendas. The development of digital competence is focused on educational contexts where students can become active players in their learning (Pettersson Citation2018) and what this looks like within the TYP is largely unknown.

Constructionism for learning

Papert introduced constructionism in 1980 as a framework for learning that involves creating artefacts with others to gain understanding (Papert Citation1980; Tissenbaum et al. Citation2021; Citation2017). Central to constructionism is the belief in respecting learners as creators and providing them with access to powerful tools. In their book, Holbert, Berland, and Kafai (Citation2020) analyse, reformulate, and advance the constructionist paradigm, considering innovative technologies and theories. Research explores various contexts, including schools, homes, and virtual spaces, and examines ways to support underprivileged or marginalised learners (Tissenbaum et al. Citation2021; Citation2017). Collaboration and the creative process of construction are also highlighted, along with strategies for nurturing creativity within the confines of formal educational environments (Holbert, Berland, and Kafai Citation2020) such as the TYP. ‘Constructionism respects the learner beyond any curriculum, institution, or system. And valuing the learner, their experiences, perspectives, and needs – also means valuing their frustration, their anxiety, and their anger. Constructionist design must create space for students to be unhappy, disruptive, and disrespectful’ (Holbert, Berland, and Kafai Citation2020, 165). ‘Constructivism focuses on students being actively engaged in doing rather than passively engaged in receiving knowledge. PBL can be viewed as one approach to creating learning environments in which students construct personal knowledge’ (Moursund Citation2002, 35).

Project-based learning

PBL designers have the responsibility not only to facilitate student-led learning and construction on a daily basis but also to adapt and reconfigure the learning context, social arrangements, material choices, and activities to enable the unrestricted exchange of learners’ social and cultural experiences across different spaces they navigate (Holbert, Berland, and Kafai Citation2020; Boss & Krauss, Citation2014). Boss and Krauss, (Citation2014) discuss the evolution of PBL can be traced back to John Dewey's conceptualization of an iterative process driven by reflective analysis of outcomes. Dewey emphasised the importance of acting, reflecting on the results, and using that analysis to inform further iterations in the learning process (Boss and Krauss Citation2014). This includes considering the context influences outside the confines of the learning environment, whether virtual or physical. ‘Becoming a skilled Project Based Teacher does not happen with one project. It is an ongoing process of professional learning and reflection, supported by effective school leaders, instructional coaches, and teaching colleagues’ (Boss & Krauss, 2018, p. 27). PBL involves students engaging in open-ended inquiries and using their knowledge to create genuine and meaningful outcomes (Moursund Citation2002). A key aspect of PBL is that the teacher facilitates but does not direct (Moursund Citation2002). Projects often provide students with the freedom to make choices, fostering active learning and collaborative teamwork (Boss and Krauss Citation2014) to facilitate the development of digital competence (Pettersson Citation2018). Within post primary education research there is a focus on what is next within digital spaces, students’ development of twenty-first century skills and creativity within the programmes (Bray et al. Citation2023a; Citation2023b; Citation2021). Strangely, the TYP’s most common mode of assessment is through an ePortfolio (NCCA Citation2022) and there is no research on ePortfolios within the TYP. EPortfolio research reveals the benefits and challenges associated with them as a form of assessment, moving away from written exams and into the twenty-first Century model (Farrell et al. Citation2021).

Why chose a constructionism and project-based learning approach in the TYP?

A constructionist learning environment focused on PBL that truly listens to the learners must be responsive to the broader context that extends beyond its immediate boundaries (Holbert, Berland, and Kafai Citation2020; Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979) when developing DS in the TYP. ‘Through academically rigorous projects, students acquire deep content knowledge while also mastering twenty-first century success skills: knowing how to think critically, analyse information for reliability, collaborate with diverse colleagues, and solve problems creatively’ (Boss & Krauss, 2018, p. 19).

The TYP focuses on project-based learning throughout all aspects of the curriculum and furthermore promotes constructionism as an approach to teaching and learning (NCCA Citation2022). The adoption of a constructionism and PBL approach in DS is driven by significant advantages for the developing digital world. Another essential aspect of PBL in the TYP is technology integration, where students have access to digital tools, software, and online resources that enhance their learning experiences and foster digital literacy and technological competence (O’Regan, Brady, and Connolly Citation2022; Connolly et al., Citation2022; Zhang & Wang, Citation2018). Utilising technology for research, data analysis, multimedia creation, and communication further develop students’ digital skills and accommodates the needs of students with diverse learning requirements (O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021; O’Sullivan et al. Citation2023).

These approaches actively engage learners, involving them in direct activities and problem-solving tasks to stimulate their curiosity and critical thinking skills (Tissenbaum et al. Citation2021; Citation2017). By providing authentic learning experiences, students can apply their knowledge in practical contexts, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter (Holbert, Berland, and Kafai Citation2020). Constructionism and PBL allow for personalisation and individualisation, catering to the unique needs and interests of students (Lane, McGarr, and Nicholl Citation2023). Collaboration and communication are also emphasised, promoting teamwork and people skills as well as constant reflection (Boss and Krauss Citation2014). Furthermore, these approaches develop higher-order thinking skills, encourage reflection, and enhance motivation and ownership of learning, and cultivate transferable skills necessary for future success (Moursund Citation2002; Papert Citation1980). Overall, constructionism and PBL provide a dynamic and effective educational environment that prepares learners for the challenges in DS.

Gap year considerations

The TYP on offer in post-primary education in Ireland is not seen in other countries and more often seen after formal education has ended. The TY as an outlier programme internationally is innovative in its very core of development in Irish education, despite this it has been under researched. The TYP is a gap year between the formal education setting of Junior Cycle and Senior Cycle and is embedded within the school’s organisation and context, completely individual to Ireland. A gap year can be defined as a period in ‘which an individual takes out of formal education in the context of a longer-term career trajectory’ (Jones Citation2004). A gap year is flexible and can involve unstructured activities, part-time work, volunteering, leisure activities, emotional and social development with gap year students undertaking or combining these distinctive and unique activities at different points throughout their gap year (Jones Citation2004; Martin Citation2010). A gap year internationally is commonly experienced after students’ high school/secondary education has ended and before starting third level education/university or entering the workforce (Martin Citation2010). Several definitions for the term ‘gap year’ are used in the literature on adolescents who delay entry to further and third level education, however, there is little consistency in the use of the term ‘gap year’ between studies. Previous studies internationally suggest that taking a gap year might contribute to increased self-development, higher performance outcomes, better career choice formation, and an increase in a variety of life skills such as leadership, communication, and self-discipline (Jones Citation2004; Martin Citation2010). This is particularly relevant in Ireland where better exam results are seen in the Senior Cycle where students participate in the gap TYP (Clerkin, Citation2018; Hayes and Childs Citation2012; Jeffers Citation2011; Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004). The opportunity to explore new extra-curricular activities, new friends, career paths, and sample subjects (Prendergast and O'Meara Citation2016) in the low-stakes environment of TY is also widely valued (Clerkin, Citation2018) and impacts on decisions going forward into the senior cycle and leaving certificate.

Although gap years have become increasingly commonplace over recent decades, they are still less common among disadvantaged groups within the TY and internationally after secondary education (Greenspon Citation2017; Clerkin, Citation2018). The increase in gap years internationally has been seen as a response to increased participation in further education and opportunities available after secondary education. Gap years bridging the time between formal education and examinations is a way for adolescents and young people to gain social and emotional maturity, improve their experiences in practical first-hand activities and gain essential experience over their fellow peers/competitors. Many of the international studies define any period spent away from formal, full-time studies after secondary school education is considered a gap year, however for this research the TY within secondary education in Ireland qualifies under the same headings and will be considered a gap year as well. Greenspon (Citation2017) notes how the growing number of international corporation’s support gap years and emphasise ‘strengthened employability’ as a selling point. The growth in gap years has been synchronous with the rise of a demand for individual and varied experiences which are compelling adolescents to demonstrate individual employability (Greenspon Citation2017) far younger than previous generations clear in Ireland where a gap year appears within post-primary education, is the Irish education system pushing life skills earlier on than their international counterparts?

In general, opting for a gap year seems advantageous for these young people (Greenspon Citation2017); however, the effects of a gap year are contingent upon factors such as the individual's socioeconomic status and the specific activities engaged in during the gap year. Although additional research is needed to firmly establish the conclusion that gap years are beneficial for PBL and the development of digital competence, the existing evidence suggests a positive trend in this regard.

Literature search

The methods section is optional in narrative reviews but can enhance clarity (Ferrari Citation2015). Conducting a literature search with well-defined keywords and inclusion/exclusion criteria is crucial (Ferrari Citation2015; Winter Citation2023). For this study, three databases were searched using specific terms, with inclusion criteria for articles published in education and related to the TYP. Exclusion criteria included articles without full text availability, non-English articles, and grey literature. Additional references were identified through manual searches. It is recommended to consult diverse information sources, avoid excessive reliance on specific research groups or journals, and prioritise original articles (Winter Citation2023). The selection process can be refined, documented in a summary table or reference cards, and filed with proper citation style (Winter Citation2023) .

Table 1. Manuscripts analysed.

The transition year programme

In this section on origins, the evolution of the TYP in Ireland is traced from the late 1970s to the present. It explores several significant advancements and places them within the context of pertinent political and societal factors prevailing during the respective periods. This section reviews the past and present literature in relation to the TYP.

The TYP in Ireland is often strongly associated with PBL methodologies. The TYP provides an ideal framework for the implementation of PBL approaches due to its emphasis on student-centred and experiential learning. During the TYP, students can engage in extended projects that allow for in-depth exploration of topics and the application of knowledge and skills in real-world contexts. These projects typically involve open-ended questions, collaborative teamwork, and authentic outcomes. By incorporating PBL into the TYP, students not only develop subject-specific knowledge but also enhance their critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, and collaboration skills. PBL within the TYP fosters student autonomy, creativity, and a sense of ownership over their learning, promoting a deeper and more meaningful educational experience.

What is the transition year programme?

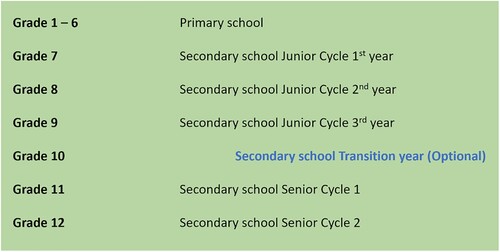

The TYP in Ireland is an optional one-year programme offered to students aged 15–16 in post-primary schools, serving as the first year of a three-year senior cycle (DoE Citation1993). It acts as a transitional phase between the Junior Certificate and Leaving Certificate programmes, preparing students for entry into higher education or further studies. The TYP is considered unique and innovative within the education system in Ireland and internationally, as it lacks comparable interventions in standardised systems (Clerkin Citation2013; Jeffers Citation2011). Notably, the TYP has influenced the development of similar programmes, such as the Free Year Programme in South Korea, which emphasises student well-being and an integrated approach to education, prioritising a break from high-stakes assessments (Clerkin, Jeffers, and Choi Citation2022). There is a current (NCCA Citation2021; Citation2022) review of the TYP underway as part of the review of the Senior Cycle years in Ireland with a desire to ensure the programme is keeping up with changes in society and policy .

Development of the TYP

The development of the TYP in Ireland spanned several decades, evolving in response to various educational, societal, and political influences. The origins of the TYP can be traced back to the late 1970s when it was first introduced as a response to concerns about the narrow focus of the Leaving Certificate examination and the need for a more integrated approach to education (Hayes and Childs Citation2012).

The initial phase of development involved pilot projects and experimental initiatives in a small number of schools (Jeffers Citation2007). These early initiatives aimed to explore alternative educational models that would provide students with a broader range of experiences, beyond the traditional academic curriculum.

Over time, the TYP gained recognition and support from educational policymakers, leading to its formal establishment as a national programme in the early 1990s (Jeffers Citation2011). Its inclusion in the curriculum was driven by the desire to offer students an additional year of education between the Junior Certificate and Leaving Certificate examinations, focused on personal development, life skills, and exploration of various subjects and disciplines.

The TYP continued to evolve in response to changing societal and educational needs (Smyth Citation2016; Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004). It incorporated elements such as work experience, community engagement, and PBL, providing students with opportunities to apply their knowledge and skills in real-world contexts (Moynihan Citation2015). This approach aimed to enhance student engagement, critical thinking, and personal growth. The TYP development process involved ongoing evaluation, research, and collaboration between educational stakeholders, including teachers, policymakers, and students. This collaborative effort ensured that the programme remained responsive to emerging trends in education, societal demands, and the evolving needs of students.

Today, the TYP is an established part of the Irish education system, offering students a unique and valuable educational experience that goes beyond the confines of traditional academic subjects. Its development over the years has been driven by the goal of providing students with a well-rounded education, fostering personal development, and preparing them for future challenges and opportunities .

Table 2. Timeline of the TYP in Ireland.

Research of the TYP

This literature review provides a comprehensive analysis of the TYP within the Irish educational system. Through an examination of various research studies, evaluations, reports, and practitioner reflections, the review aims to assess the impact, benefits, challenges, and effectiveness of the TYP. The findings highlight the programme's positive influence on holistic development, offering diverse educational experiences, enhancing student engagement and motivation, fostering skills development, providing transitional support, and eliciting favourable perspectives from students. However, challenges related to implementation, resource constraints, and the need for effective monitoring and evaluation are also identified. The review concludes by emphasising the Department of Education and Skills’ guidelines for implementing the TYP, which stress the importance of creating a space for students to learn, mature, and develop without the pressure of examinations (NCCA Citation2022). The goal is to prepare them to become autonomous, participative, and responsible members of society (DoE Citation1993). The review suggests implications for further education and recommends avenues for future research in this area.

Revealed themes of this narrative literature review will now be revealed in relation to.

Holistic Development and Personal Growth

Broadening Educational Experiences

Student Engagement and Motivation

Skills Development

Transitional Support

Challenges and Considerations

Positive and Negative Perspectives

Transition Year and Further Education

Holistic development and personal growth

This section of the literature review delves into the research findings that specifically focus on the impact of the TYP on students’ personal, social, and emotional development. The studies examined highlight various positive outcomes associated with the TYP, shedding light on its significant influence on students’ growth and well-being.

One prominent area of impact is the TYP's role in facilitating self-discovery among students (NCCA Citation2022). By providing a supportive and nurturing environment, the programme allows students to explore their interests, passions, and talents. This process of self-exploration has been found to contribute to improved self-esteem, as students gain a deeper understanding of their abilities and potential (Clerkin Citation2013). Moreover, the TYP fosters the development of interpersonal skills, such as effective communication, teamwork, and collaboration (Jeffers Citation2015; Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004). Through group activities, projects, and community engagement, students have many opportunities to interact with their peers, build relationships, and enhance their social competencies (Clerkin, Jeffers, and Choi Citation2022).

Another significant outcome observed in the literature is the increased confidence displayed by TYP participants particularly after engaging in new experiential learning opportunities (Ng et al. Citation2019; Zhang & Wang, Citation2018) and developing student voice (Dempsey Citation2001). Engaging in a wide range of experiential learning activities, including work placements, practical projects, and community service, students gain a sense of accomplishment and competence, which in turn boosts their self-confidence (Clerkin Citation2013). This is particularly noteworthy for disadvantaged students who may have faced various challenges or limitations in their educational journey (Jeffers Citation2002; Marcus-Quinn et al., Citation2019). The TYP offers a supportive environment where they can thrive, and their achievements contribute to a positive sense of self and greater belief in their capabilities while appreciating other ethnicities and cultures (Tormey and Gleeson Citation2012).

In addition to personal development, the TYP has been found to have a positive impact on students’ socioemotional well-being (Clerkin Citation2019). The programme provides a holistic and inclusive educational experience, focusing not only on academic learning but also on the emotional and social aspects of students’ lives. This comprehensive approach contributes to the development of students’ emotional intelligence, resilience, and empathy (Clerkin, Jeffers, and Choi Citation2022). The TYP creates an environment where students feel supported, valued, and empowered, leading to greater overall well-being and a sense of belonging within the school community.

Furthermore, the studies conducted by Clerkin (Citation2012), Jeffers (Citation2011), and Hayes and Childs (Citation2012) consistently highlight the positive experiences reported by both students and teachers in relation to the TYP. Students express elevated levels of satisfaction, enjoyment, and motivation during their participation in the programme. Teachers also recognise the benefits of the TYP, acknowledging its potential in promoting student engagement, active learning, and personal growth. This alignment between student and teacher perspectives underscores the positive impact of the TYP on the educational experience.

It is also worth noting that the inclusion of exchange students from diverse cultural backgrounds in the TYP has been found to challenge attitudes towards ethnic minorities and promote positive changes among participants (Tormey and Gleeson Citation2012). This aspect of the programme fosters intercultural understanding, empathy, and appreciation for diversity, contributing to a more inclusive and tolerant learning environment (Jeffers Citation2007) and aids students wellbeing (Clerkin Citation2019).

Overall, the literature provides compelling evidence of the TYP's significant impact on students’ personal, social, and emotional development. Through self-discovery, improved self-esteem, enhanced interpersonal skills, increased confidence, and socioemotional well-being, students benefit greatly from their participation in the programme. The positive experiences reported by both students and teachers further reinforce the value and effectiveness of the TYP in facilitating holistic growth and fostering a positive school climate.

The TYP's significant impact on students’ personal, social, and emotional development through self-discovery, improved self-esteem, enhanced people skills, increased confidence, and socioemotional well-being, students derive substantial benefits from their participation in the programme. The positive experiences reported by both students and teachers further reinforce the value and effectiveness of the TYP in facilitating holistic growth and fostering a positive school climate (Dempsey Citation2001).

Holistic development and personal growth in the TYP plays a pivotal role in nurturing students’ comprehensive development, and this theme aligns well with the principles of PBL and digital spaces in education. PBL, resonates strongly with the TYP's goals of enhancing students’ self-esteem, communication skills, and overall personal growth. Digital spaces can serve as dynamic platforms for students to engage in collaborative problem-solving, foster effective communication, and showcase their newfound confidence and skills. Moreover, the TYP's inclusive approach to education, as highlighted in the literature, can be further enriched through digital means by facilitating interactions with diverse cultural backgrounds and promoting intercultural understanding and empathy. Thus, the convergence of PBL principles and digital spaces within the TYP holds the promise of creating a powerful educational environment that not only fosters holistic growth but also prepares students for the complexities of the digital age.

Broadening educational experiences

This section of the literature review focuses on the diverse range of learning experiences offered by the TYP beyond the conventional academic curriculum. The research highlights various components of the programme, such as subjects, direct activities, community engagement, work experience, and PBL, which collectively contribute to a comprehensive educational journey. Scholars have recognised the TYP as an innovative initiative within the Irish education system, providing students aged 15–16 with an opportunity to explore their personal interests and foster maturity through a wide array of educational and practical experiences, free from the pressure of high-stakes assessments (Department of Education Citation1993).

One notable shift in the TYP is the move away from a homework-centric approach towards a more practical learning style. This transition has been found to positively influence students’ attitudes and approaches to homework during their Senior Cycle years (Clerkin Citation2016). Moreover, the responsibility for setting appropriate goals and defining objectives tailored to the individual needs of students lies with the schools, which can employ various assessment methods, including continuous assessment, end-of-year interviews, portfolios of achievement, and presentations of students’ accomplishments (DoE Citation1993; Lawlor et al. Citation2018; O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021).

The curriculum of the TYP varies among schools, with core subjects like English, Irish, and Maths still being maintained, while optional subjects such as Art, Music, Construction, Engineering, Information and Technology, and Home Economics are introduced to students for exploration and to help them determine the subjects that best align with their interests and goals for the Leaving Certificate. The TYP represents a departure from the uniformity of education experienced prior to this stage, offering students a valuable opportunity to develop essential social and professional skills without the constraints of rigid, test-oriented learning. Both teachers and students are encouraged to customise TYP courses or short modules based on the students’ interests and skills, incorporating a wide range of optional modules and competitions (Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004; Zhang & Wang, Citation2018) such as the BT Young Scientist & Technology Exhibition, Formula1 in schools, Young Social Innovators, AIB Build a Bank, Certified Irish Angus Schools Competition, Student Enterprise, CoderDojo, Gaisce, European Youth Parliament, and many others. These additional modules and competitions provide students with eye-opening educational opportunities (Prendergast and O'Meara Citation2016).

It is important to note that due to the diverse nature of the TYP curriculum, numerous opportunities for students are available (O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021). However, it is also worth considering that the TYP can serve as an introductory year to the intense and pressurised Leaving Certificate system, where teachers may focus on thoroughly covering the curriculum content in a detailed manner, shedding light on the demanding nature of the Leaving Certificate.

The TYP offers modular courses that provide certification for specific purposes. These certifications include the Student Enterprise Awards, Young Social Innovator (YSI), GAA coaching (Gaelic Athletic Association – Football), European Computer Driving License (computer course), First Aid, Tourism Awareness, Amber flag (NCCA Citation2022; Ng et al. Citation2019) and An Gaisce, which is dedicated to fostering personal development and social agency in young people (Professional Development Services for Teachers Ireland Citation2022). These additional certifications enhance students’ skill sets and contribute to their overall personal and professional growth. Adventure activities, a prominent feature of the curriculum, provide students with active outdoor learning experiences (Pierce, Citation2021).

The TYP's ability to provide a broad range of learning experiences beyond the traditional academic curriculum was explored in this section. The programme's innovative nature, emphasis on practical learning, customization of courses, and inclusion of optional modules and competitions contribute to students’ educational journey, enabling them to develop essential skills and explore their interests (O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021; Pierce, Citation2021). The TYP serves as a bridge to the intense Leaving Certificate system, while also offering modular courses that provide certifications for specific purposes, further enhancing students’ skill sets and personal development (Bray, Girvan, and Ni Chorcora Citation2023b).

Broadening educational experiences in the TYP signifies an essential shift towards diverse and practical learning opportunities beyond traditional academics. This theme aligns with the principles of problem-based learning and underscores the potential of digital spaces in education. PBL, which emphasises real-world problem-solving and critical thinking, resonates with the TYP's hands-on approach. However, students often express confusion about the purpose of their tasks. Here, digital spaces can play a pivotal role by providing clarity, structured problem statements, and collaborative online environments, enhancing goal-oriented activity-based learning. Moreover, the TYP's customization aspect finds synergy with digital platforms, enabling tailored educational experiences that cater to individual interests. Digital resources, online courses, and virtual tools empower students to explore their passions while fostering self-directed learning. Thus, this convergence of pedagogical innovation and digital technology promises to enrich the TYP.

Student engagement and motivation

The TYP has a significant impact on student engagement and motivation (Jeffers Citation2015). These findings suggest that students experience heightened levels of enjoyment, interest, and active participation in their studies during the TYP year, which can be attributed to the programme's experiential and student-centred approach (Clerkin Citation2012; Citation2013). The TYP is implemented in approximately 75% of Post Primary schools in Ireland (Clerkin Citation2019), indicating the widespread recognition and success of adopting a more flexible approach to learning and personal development.

A central aspect of the TYP is the emphasis on developing basic competences in key areas tailored to the individual needs of students, including remediation for those who may otherwise be disadvantaged (NCCA Citation2022). This personalised approach ensures that students are provided with the necessary support and opportunities to engage meaningfully in their learning.

TYP has been shown to have a positive impact on student engagement and motivation (Clerkin Citation2018a). The programme's experiential and student-centred approach allows students to actively participate in their studies and explore different areas of interest (Prendergast and O'Meara Citation2016). By providing a more flexible learning environment, the TYP encourages students to take ownership of their learning and engage in hands-on experiences (Lawlor et al. Citation2018; O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021). The heightened levels of enjoyment and interest experienced by students in the TYP can be attributed to the programme's emphasis on experiential learning (Clerkin Citation2018b). Through practical projects, work experience placements, community engagement, and other activities, students can apply their knowledge and skills in real-world contexts (Ng et al. Citation2019). This hands-on approach fosters a deeper understanding of the subject matter and helps students see the relevance and applicability of what they are learning.

The student-centred nature of the TYP acknowledges the diverse interests and talents of students. It provides them with the freedom to explore different subjects, pursue personal projects, and develop skills beyond the traditional academic curriculum with active promotion of their student voice (Dempsey Citation2001). This flexibility and autonomy in learning contribute to increased motivation and engagement among students (Jeffers Citation2007). The wide adoption of the TYP in approximately 98% of Post Primary schools in Ireland reflects the recognition of its benefits and success (NCCA Citation2022). The programme provides an alternative to the traditional Junior Certificate curriculum and offers students a valuable year of personal and social development. By incorporating experiential learning, student-centred approaches, and flexibility into the curriculum, the TYP promotes active engagement, motivation, and holistic growth among students.

The TYP's experiential and student-centred approach aligns well with the principles of PBL, as both methodologies emphasise active participation, exploration, and firsthand experiences. These characteristics naturally lead to increased enjoyment and interest in learning, as students see the relevance and applicability of what they are studying. Additionally, the flexible nature of the TYP, allowing students to pursue their interests and develop skills beyond the traditional curriculum, echoes PBL's emphasis on self-directed learning and autonomy. In the context of digital spaces, technology can play a pivotal role in enhancing student engagement by providing interactive learning experiences, facilitating research, and enabling creative projects. Moreover, digital spaces can offer personalised learning opportunities, catering to individual needs and interests, thereby contributing to increased student motivation. The TYP's success in promoting student engagement and motivation is closely tied to the principles of PBL and the potential of digital spaces to create dynamic and personalised learning environments.

Skills development

The literature delves into the impact of the TYP on the development of critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork, and communication skills in students. Various research studies highlight how the TYP facilitates the practical application of knowledge, thereby promoting the acquisition of transferable skills crucial for continued education and future professional endeavours. Throughout the TYP, students are encouraged to actively participate in independent and self-directed learning, enabling them to cultivate a range of general, technical, and academic proficiencies while experiencing personal growth and development, free from the constraints of high-stakes examinations (NCCA Citation2022).

The Bridge21 model promoted in DS increased student motivation and was effective in helping students develop twenty-first Century skills through PBL activities (Lawlor et al. Citation2018) as a positive impact on students’ critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork, and communication skills. However, challenges arise in implementing skills-based curricula, as teachers may be concerned about assessing and certifying students’ skills, and there may be pressures within the TYP to prepare students for their future Leaving Certificate examinations (Johnston et al. Citation2012).

Through practical application and independent learning, students acquire transferable skills necessary for their education and future careers (Moynihan Citation2015; O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021). In the context of Chinese language development in the TYP, Zhang and Wang (Citation2018) suggest that the use of digital technologies can provide equal opportunities for students to explore the language, especially when teachers may not be as confident in their own language abilities. “The students learn by doing, so also do the teachers learn by trying out new things as they devise, develop, resource and evaluate their own teaching modules” (Dempsey Citation2001, 106), this is significant for this research and acknowledges the teachers and students as negotiators throughout the TYP. Farrell et al. (Citation2021) focus on eportfolios as they can creatively showcase students’ skills and knowledge, however this is not researched in relation to the TYP despite being one of the most used forms of assessment in the TYP.

The TYP review (NCCA Citation2022) acknowledges that the absence of external assessments in the programme is seen as both a strength and a weakness. Schools have developed innovative approaches, such as credit-based systems, to assess and recognise student learning in the TYP. These practices merit consideration when developing the revised programme statement. However, the extent to which centrally prescribed credit systems could be implemented needs careful examination. The introduction of a centrally devised credit system may risk a loss of autonomy for schools in designing their TYP programmes and assessing student learning. Furthermore, there is a potential risk of reducing the creativity and innovation that currently characterise good practice in the TYP.

The TYP's focus on practical application and independent, self-directed learning aligns with the principles of PBL, emphasising the acquisition of transferable skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork, and communication. This firsthand approach in the TYP promotes active skill development through real-world experiences, mirroring PBL's focus on applying knowledge to authentic situations. Additionally, the incorporation of digital technologies within the TYP, as highlighted in the context of Chinese language development, underscores the role of digital spaces in skill development. Digital tools provide opportunities for students to explore subjects and languages, particularly when teachers may have limitations in their own expertise. The use of e-portfolios as a form of assessment further illustrates the integration of digital spaces in skill showcasing and assessment within the TYP. However, challenges arise in assessing and certifying these skills, as well as balancing the need for skills development with traditional examination preparation, as noted in the review of the TYP. In summary, the TYP's emphasis on skills development is intricately linked to PBL principles and leverages digital spaces to enhance skill acquisition and assessment.

Transitional support

This section discusses the TYP's significance as a transitional year between the Junior Certificate and Leaving Certificate examinations. It presents research findings that highlight the programme's role in supporting students’ academic and personal growth (Clerkin Citation2012), aiding their adjustment to the demands of senior cycle education, and facilitating a smoother transition process. The TY reinforces the efforts from the Department of Education and Skills to provide ‘a bridge to help pupils make the transition from a highly structured environment to one where they will take greater responsibility for their own learning and decision making’ (Dept. of Education Citation1993, 2). However, for the successful implementation of the TYP, key challenges remain, from students’ abilities to ‘reflect on and develop an awareness of the value of education and training in preparing them for the ever-changing demands of the adult world of work and relationships’ (Dept. of Education Citation1993, 2) to teachers capacities and autonomy to enact the 45 timetabled hours of ‘shorter modules and other learning experiences’’ (Dept. of Education Citation1993, 2).

However, the successful implementation of the TYP is not without its challenges. Students face difficulties in reflecting on and developing an awareness of the value of education and training in preparing them for the ever-changing demands of the adult world of work and relationships (Jeffers Citation2010). Teachers also face challenges in terms of curriculum change (Byrne & Prendergast, Citation2020), their capacities and autonomy to deliver the forty-five timetabled hours of shorter modules and other learning experiences as required by the TYP curriculum (Gleeson Citation2012).

The TYP plays a crucial role in facilitating students’ transitions from post-primary education to third level and from Junior Cycle to Senior Cycle, as identified by Mooney et al. (Citation2014). The influence of school culture on the implementation of the innovative TYP has also been recognised, with Jeffers (Citation2007) noting its impact on students’ development and preparation for the next steps in academia.

PBL often incorporates real-world scenarios and practical problem-solving, which are valuable for students in preparing for the challenges of senior cycle education. Additionally, the use of digital spaces and technologies within the TYP can facilitate the transition process, as students become more accustomed to self-directed learning and digital tools commonly used in higher education and the professional world. However, challenges related to students’ understanding of the value of education and teachers’ capacity to deliver the diverse TYP curriculum should be addressed to maximise the programme's effectiveness in this transitional role. Overall, the TYP's role in transitional support is intricately linked to PBL principles and can be enhanced through the strategic use of digital spaces and tools.

Challenges and considerations

While the TYP has shown promise in enhancing student engagement and promoting essential skills, its successful implementation is not without challenges. The Challenges and Considerations section discusses the obstacles related to implementing the TYP, such as disparities among schools, limited resources, and the significance of monitoring and evaluation. It emphasises the importance of ensuring consistency, quality, and coherence in TYP experiences across various educational contexts (Clerkin Citation2018b). The primary constraints identified for the successful operation of the TYP are time limitations and inadequate financial resources for funding activities and outings (Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004). Ensuring consistency, quality, and coherence in TYP experiences across diverse educational contexts is crucial to provide equitable access and high-quality education for all students (Jeffers Citation2002; Johnston et al. Citation2012).

The TYP experiences significant variations in implementation approaches, curricula, and activities across different schools. This can result in inconsistencies and inequities, as students from various schools may have differing TYP experiences. Establishing standardised guidelines and frameworks that ensure consistency in programme delivery is crucial to ensure equitable access and quality education for all students. Given that the TYP typically spans a single academic year, time constraints pose challenges to fully realising the programme's potential. The limited duration may restrict students’ ability to engage deeply with the diverse range of activities and experiences. Balancing the breadth of opportunities with sufficient time for reflection and consolidation of learning becomes crucial for optimising the impact of the TYP (O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021). Exploring innovative solutions to overcome resource limitations, establishing effective monitoring and evaluation processes, and managing available time judiciously are critical aspects of operating and continuously improving the TYP (Farrell et al. Citation2021).

Furthermore, challenges related to implementing eportfolios for assessment in higher education institutions (Farrell et al. Citation2021) highlight the need to consider potential hurdles in using eportfolios within the TYP, even though research specific to eportfolios in the TYP context is lacking. In the face of these challenges, the TYP review (NCCA Citation2022) recognises the importance of empowering students to navigate and contribute meaningfully to complex issues in the twenty-first century, such as climate breakdown, evolving work patterns, and increasing digitalisation of society. By addressing the identified challenges and responding to global trends, the TYP can better fulfil its purpose of fostering students’ holistic development and preparing them for future educational and professional endeavours.

While not explicitly tied to PBL, these challenges have indirect connections to PBL principles and digital spaces. For instance, the disparities among schools in implementing the TYP can impact the consistency and quality of students’ experiences with digital devices such as tablets (Coyne and McCoy Citation2020), which is a key concern in PBL where equitable access to resources and opportunities is crucial. Additionally, the effective use of digital spaces and tools can help address some of these challenges, such as resource limitations and monitoring and evaluation processes. However, challenges related to eportfolios in higher education institutions highlight the need for careful consideration when incorporating digital assessment tools in the TYP context. Overall, addressing these challenges requires a collaborative effort to ensure that the TYP continues to provide valuable educational experiences and prepares students for the evolving demands of the twenty-first century.

Perspectives

Perspectives on the TYP from various stakeholders have been explored, shedding light on the programme's reception and impact. Students generally express positive feedback about the TYP (Jeffers Citation2007) valuing the opportunities it provides for self-exploration, learning autonomy, and personal development (Dempsey Citation2001; Smyth Citation2016). However, students who are less positive about their overall school experience, especially in schools where the programme is compulsory, may hold more negative views about the TYP (Clerkin Citation2019; Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004). Students reflections on informal learning environments within in the TYP and outside of the classroom revealed that the capacity of the teachers to engage with the students and the relationship between them are crucial for positive outcomes and experiences (O’Regan, Brady, and Connolly Citation2021; Citation2022).

School principals and teachers tend to view the TYP as successful, particularly in developing students’ personal and social skills (Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004). However, perspectives can vary among school principals, with those in designated disadvantaged schools, smaller schools, and vocational sectors potentially having less favourable perceptions of the program due to specific contextual challenges (Clerkin Citation2018b). Particularly in relation to the role of management within the school as a form of leadership for the teachers and students alike (Jeffers Citation2010)

Parental perspectives on the TYP also exhibit a degree of variation. Some parents hold positive views, recognising the programme's benefits in fostering holistic development, experiential learning, and exploration of different subjects and career options (Smyth Citation2016). Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that there can be mixed opinions and concerns among parents (Clerkin Citation2018c). Some parents may express reservations about the perceived lack of structure or potential gaps in academic content during the TYP (Jeffers Citation2015). Socio-economic background and educational attainment can also influence parental perspectives on the TYP, with parents from disadvantaged backgrounds potentially having different views due to variations in programme implementation and available resources across schools (Clerkin Citation2018c; Jeffers Citation2002). Furthermore, parents from lower socio-economic groups may harbour concerns about the TYP's impact on their child's future educational and career prospects (Moynihan Citation2015).

While the TYP is generally viewed positively by many stakeholders, including students and educators, there can be a range of opinions and concerns regarding its impact on academic progress and future outcomes (Hayes and Childs Citation2012; Jeffers Citation2002). Understanding these varied perspectives is crucial for policymakers and educators to continually enhance the programme's effectiveness and inclusivity, addressing specific challenges and meeting the diverse needs of students and their families.

Although not explicitly connected to PBL or digital spaces, these perspectives have indirect links to these concepts. For example, students’ positive feedback on the TYP often revolves around self-exploration and learning autonomy, which align with PBL principles of student-centeredness and independent inquiry. Additionally, students’ varying experiences and opinions highlight the need for a flexible and adaptable curriculum that can leverage digital spaces to cater to diverse learning preferences. Similarly, teachers and principals’ perceptions of the TYP's success in developing personal and social skills resonate with the collaborative and interpersonal aspects of PBL. Overall, understanding these perspectives is critical for refining the TYP's design and ensuring it remains a valuable and inclusive educational experience for all stakeholders.

Transition year and further education

This section examines the impact of the TYP on students’ academic achievements and educational pathways. Research indicates that participation in the TYP is associated with positive academic achievements and educational pathways. Students who engage in the TYP tend to achieve higher grades in their Leaving Certificate exams and are more likely to pursue higher education (Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004). While the TYP generally demonstrates positive outcomes, not all students experience academic improvement due to participating in the programme (Jeffers Citation2002; Citation2007). Factors such as part-time work and the compulsory nature of the TYP in some schools can influence the academic benefits for certain groups of students (Smyth Citation2016).

Moreover, the TYP plays a crucial role in shaping students’ subject choices in the senior cycle and aids in developing a clearer focus on future career possibilities (Clerkin Citation2019; Moynihan Citation2015). Work experience programmes within the TYP positively impact students’ academic performance and vocational identity development. The programme also exposes students to alternative learning and assessment methods, both within the school community and in real-world work environments (Jeffers Citation2011; Citation2015; Ng et al. Citation2019).

Despite the positive outcomes, there is a need for further research to understand the specific mechanisms through which the programme leads to success for students and teachers (Clerkin, Citation2018). The experiences and outcomes of the TYP can vary among schools due to differences in offered subjects, work experience placements, and assessment methods (Lawlor et al. Citation2018; O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021). Addressing these variations and providing support for schools’ implementation efforts can contribute to maximising the positive impact of the TYP on students’ academic achievements and educational trajectories.

This section highlights the potential for integrating these elements into the TYP to enhance its impact further. For instance, the TYP's role in improving study skills and fostering successful transitions to higher education aligns with the self-directed learning and research skills promoted by PBL. Digital spaces can serve as valuable tools for facilitating independent research, collaborative problem-solving, and project-based assessments, all of which can contribute to improved academic outcomes. Additionally, the TYP's exposure to alternative learning and assessment methods sets the stage for the integration of digital platforms and tools to support varied teaching and evaluation approaches. Hence, the future pathways of the TYP may involve a more deliberate integration of PBL and digital spaces to maximise its benefits for students’ academic achievements and personal development.

Discussion

This paper aimed to examine the broader historical context surrounding the TYP in Ireland and the trends that have propelled its development and advancement in PBL in DS. In conclusion, previous research has yielded mixed findings regarding the outcomes of taking a gap year, with the benefits and drawbacks being unclear and sometimes contradictory. There is a clear need for more research into DS in education (Bough and Martinez Sainz Citation2022) for the development of student’s digital competence and PBL in the TYP. Some studies suggest that the TYP enhances students’ self-development and facilitates self-exploration, aiding them in identifying their values, interests, and academic preferences for future studies (Clerkin Citation2018a; Citation2018b; Citation2019). However, previous research has also highlighted potential drawbacks, such as decreased motivation to resume education and the perception of a wasted year (Clerkin, Citation2018), negative experiences among students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds (Tormey and Gleeson Citation2012), and the influence of school size and resource provisions on the suitability of the TYP for certain students (Jeffers Citation2002; Smyth, Byrne, and Hannan Citation2004).

Benefits of a PBL approach to teaching and learning in the TYP have been revealed (Lane, McGarr, and Nicholl Citation2023; Lawlor et al. Citation2018; O’Sullivan, Bird, and Marshall Citation2021) however, it remains uncertain how a flexible TYP contributes to PBL in DS and teaching and learning process within secondary education (NCCA Citation2022) and its impact on teachers and students’ development of digital competence. a glaring challenge persists as the digital proficiency of students outside the classroom often surpasses what is offered within it (Coyne and McCoy Citation2020), or teachers are expecting too much in terms of what students know (Connolly et al., Citation2022).Understanding what success looks like in relation to the context of the TYP is unclear (Clerkin Citation2019) and within PBL activities in the DS is unknown. The revealed themes of this narrative literature review on the TYP highlight the need for PBL activities in the DS in the TYP in an academic year that affords students with unique opportunities and experiences.

In the evolving landscape of education, digital competence has risen to the forefront as an essential skill set for learners (Bray, Girvan, and Ni Chorcora Citation2023b). This review of literature underscores the critical role of digital education in contemporary learning environments and the pressing need for pedagogical approaches that foster active engagement and critical thinking among students. Integrating digital literacy and critical thinking into curricula is central to enhancing students’ digital competencies (Lawlor et al. Citation2018) within the TYP for the development of digital spaces. Equipping students with the ability to critically evaluate information and engage responsibly online is essential in an era characterised by information overload and digital misinformation. Marcus-Quinn and Hourigan's focus on team-based learning activities underscores the practical application of these skills within collaborative contexts, aligning with real-world demands (Citation2022).

The Covid-19 pandemic has shed light on the challenges faced in creating high-quality digital learning resources (Connolly et al., Citation2022; Bray, Girvan, and Ni Chorcora Citation2023b; Marcus-Quinn and Hourigan Citation2022). Creating inclusive learning spaces that bridge formal and nonformal education recognises the diverse contexts in which students learn (O’Regan, Brady, and Connolly Citation2021). The flexibility to apply digital skills across various settings fosters a deeper understanding and practical application of knowledge. Bough and Martínez Sainz (Citation2022, 12) have highlighted the evolving digital spaces in education in Ireland and affirm that ‘the social construction of digital spaces needs greater engagement from key stakeholders such as teachers and learners in its development and review to accordingly prepare learners for the future.’

Future considerations

This paper has unveiled critical directions for future research in the context of PBL within DS and the TYP in Ireland. Firstly, there is a need for in-depth investigations into the specific digital skills and competencies that students develop through PBL experiences, establishing a robust connection between PBL activities and national digital competence objectives. Secondly, research should scrutinise the effective integration of digital tools within PBL in the TYP, elucidating best practices and challenges faced by teachers in harnessing technology's potential for enhancing digital literacy. Thirdly, the development of assessment methods and tools to evaluate students’ digital skills and competencies acquired through PBL in DS is imperative, considering innovative approaches like ePortfolios. Fourthly, the impact of teacher professional development programmes on PBL facilitation skills and their role in fostering digital competence among students warrants exploration. Fifthly, understanding students’ perspectives, motivations, and long-term outcomes in PBL within DS should be a focal point, informing the continuous improvement of PBL practices. Additionally, research on digital ethics, safety, and responsible use within PBL in DS is indispensable in the digital age given the new developments in Artificial Intelligence. Lastly, examining the influence of digital education policies on PBL implementation and their role in shaping teacher practices and student experiences is essential. By addressing these research directions, scholars and educators can contribute significantly to the effective integration of PBL and DS, fostering digital competence, and aligning educational practices with policy objectives.

Conclusion

This comprehensive narrative literature review provides a multifaceted analysis of the TYP within the Irish educational system and underscores its pivotal role in shaping the educational landscape. The examination of a multitude of research studies, evaluations, reports, and practitioner reflections has shed light on various facets of the TYP, revealing both its merits and challenges.

The findings highlight the positive influence of the TYP on holistic development, offering diverse educational experiences, enhancing student engagement and motivation, fostering skills development, providing transitional support, and eliciting favourable perspectives from students. This is aligned with the Department of Education and Skills’ guidelines, which underscore the importance of creating a space for students to learn, mature, and develop without the pressure of examinations (NCCA Citation2022). The goal is to prepare them to become autonomous, participative, and responsible members of society (DoE Citation1993).

However, amidst the accolades, certain challenges related to the TYP's implementation, resource constraints, and the necessity for effective monitoring and evaluation have been identified. These challenges emphasise the need for continuous improvement and refinement in the programme's design and delivery.

One noteworthy aspect brought to the fore in this review is the gap in the existing literature concerning the influence of PBL on the evolution of digital spaces in the context of the TYP. In an increasingly digitised world, where digital competence is a critical skill (DES Citation2022; EC Citation2020), understanding how PBL principles and practices shape the digital landscape of the TYP is paramount. This research endeavour could uncover innovative practices, effective strategies, and potential challenges that have the potential to inform educational policy and practice not only in Ireland but also in other educational contexts grappling with similar digital transformation initiatives.

In conclusion, while this narrative literature review has provided a comprehensive understanding of the TYP's dynamics, it also underscores the pressing need for further research that explores the symbiotic relationship between PBL and DS in this unique educational setting. This research endeavour has the potential to bridge a significant gap in the existing literature and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how the TYP prepares students for success in the digital era. As educational paradigms continue to evolve, it is imperative to stay attuned to the transformative potential of PBL within the digital spaces of the TYP and beyond.

Ethics statement

There was no empirical data collected for this paper and therefore ethical approval was not needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ashley Bough

I am a doctoral researcher in University College Dublin exploring teachers and students’ experiences in Digital Spaces in Post Primary education in Ireland. My research analyses teachers and students’ perspectives of curriculum, pedagogy, and digital spaces for engagement. I have a background as a Post Primary Mathematics and Music Post-Primary teacher of seven years with expertise in online learning, digital pedagogy, and education technology. I have a Post of Responsibility as an Assistant Principal Two in my school.

References

- Boss, S., and J. Krauss. 2014. Reinventing Project-Based Learning: Your eld Guide to Real-World Projects in the Digital age. 2nd ed. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology Education.

- Bough, A., and G. Martinez Sainz. 2022. “Digital Learning Experiences and Spaces: Learning from the Past to Design Better Pedagogical and Curricular Futures.” The Curriculum Journal 34: 375–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.184.

- Bray, A., J. Banks, A. Devitt, and E. Ní Chorcora. 2021. “Connection Before Content: Using Multiple Perspectives to Examine Student Engagement During Covid-19 School Closures in Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 40 (2): 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1917444

- Bray, A., A. Devitt, J. Banks, S. Sanchez Fuentes, M. Sandoval, K. Riviou, D. Byrne, M. Flood, J. Reale, and S. Terrenzio. 2023a. “What Next for Universal Design for Learning? A Systematic Literature Review of Technology in UDL Implementations at Second Level.” British Journal of Educational Technology 00: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13328.

- Bray, A., C. Girvan, and E. Ni Chorcora. 2023b. “Students’ Perceptions of Pedagogy for 21st Century Learning Instrument (S-POP-21): Concept, Validation, and Initial Results.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 49), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2023.101319.

- Bronfenbrenner, U.. 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Byrne, J. R., C. Girvan, and J. Clayson. 2021. “Constructionism Moving Forward.” British Journal of Educational Technology 52 (3): 965–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13094.

- Byrne, C., and M. Prendergast. 2020. “Investigating the concerns of secondary school teachers towards curriculum reform.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 52 (2): 286–306.

- Clerkin, A. 2012. “Personal Development in Secondary Education: The Irish Transition Year.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 20 (38), http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/view/1061/1022.

- Clerkin, A. 2013. “Growth of the ‘Transition Year’ Programme, Nationally and in Schools Serving Disadvantaged Students, 1992–2011.” Irish Educational Studies 32 (2): 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2013.770663

- Clerkin, A. 2016. “Homework and Study Behaviours Before the Leaving Certificate among TY Participants and non-Participants.” Irish Journal of Education 41: 5–23.

- Clerkin, A. 2018a. “Filling in the Gaps: A Theoretical Grounding for an Education Programme for Adolescent Socioemotional and Vocational Development in Ireland.” Review of Education 6: 146–179. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002rev3.3112.

- Clerkin, A. 2018b. “Context and Implications Document for: Filling in the Gaps: A Theoretical Grounding for an Education Programme for Adolescent Socioemotional and Vocational Development in Ireland.” Review of Education 6: 180–182. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002rev3.3113.

- Clerkin, A. 2018c. “Who Participates? Predicting Student Self-Selection Into a Developmental Year in Secondary Education.” Educational Psychology 38 (9): 1083–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1504004.

- Clerkin, A. 2019. “A Three-Wave Longitudinal Assessment of Socioemotional Development in a Year-Long School-Based ‘gap Year’.” British Journal of Educational Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12267.

- Clerkin, A., G. Jeffers, and S. D. Choi. 2022. “Wellbeing in Personal Development: Lessons from National School-Based Programmes in Ireland and South Korea.” In Wellbeing and Schooling. Transdisciplinary Perspectives in Educational Research. Vol. 4, edited by R. McLellan, C. Faucher, and V. Simovska, 155–172. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95205-1_10.

- Connolly, C, C. Murray, B. Brady, G. Mac Ruairc, and P. Dolan. 2022. “New actors and new learning spaces for new times: a framework for schooling that extends beyond the school.” Learning Environments Research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-022-09432-y.

- Coyne, B., and S. McCoy. 2020. “Forbidden Fruit? Student Views on the Use of Tablet PCs in Education.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education 29 (3): 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1754897

- Deane, P. 1997. The Transition Year: A Case Study in the Implementation of Curriculum Change. Master’s thesis, National University of Ireland Maynooth.

- Dempsey, M. 2001. The Student Voice in the Transition Year Programme A school-based case study. Master’s thesis, National University of Ireland Maynooth.

- Department of Education. 1993. Transition Year Programme: Guidelines for schools. (Dublin, Author). https://ncca.ie/en/senior-cycle/programmes-and-key-skills/transition-year/.

- Department of Education. 2022. The Digital Strategy for Schools to 2027. Dublin. https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file = https://assets.gov.ie/221325/9f3845ed-0f6b-43b7-81d5-ddc2ab711c43.pdf#page = null.

- Dewey, J. 1938. Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan.

- European Commission. 2020. Digital Education Action Plan. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-education-action-plan.

- Farrell, O., K. Buckley, L. Donaldson, and T. Farrelly. 2021. “Editorial: Goodbye Exams, Hello Eportfolio.” Irish Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning 6 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.22554/ijtel.v6i1.101.

- Ferrari, A. 2012. Digital Competence in Practice: An Analysis of Frameworks. Sevilla: Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Commission.

- Ferrari, R. 2015. “Writing Narrative Style Literature Reviews.” Medical Writing 24 (4): 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329.

- Gleeson, J. 2012. “The Professional Knowledge Base and Practice of Irish Post-Primary Teachers: What is the Research Evidence Telling us?” Irish Educational Studies 31 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2011.617945.

- Greenspon, Jacob. 2017. “The Gap Year: An Overview of the Issues,” CSLS Research Reports 2017-01, Centre for the Study of Living Standards.

- Hayes, S., and P. Childs. 2012, March. Science in the Irish transition year: Implications for the future of science teaching and learning. Paper presented at the Educational Studies Association of Ireland annual conference, Cork, Ireland.

- Higgins, Michael D. 2021. About GAISCE. Accessed March 29 2022. https://www.gaisce.ie/about-gaisce/.

- Holbert, N. 2016. “Leveraging Cultural Values and “Ways of Knowing” to Increase Diversity in Maker Activities.” International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction 9–10: 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2016.10.002.

- Holbert, N., M. Berland, and Y. B. Kafai. 2020. Designing Constructionist Futures: The art, Theory, and Practice of Learning Designs. MIT Press.

- Jeffers, G. 2002. “TYP and Educational Disadvantage.” Irish Educational Studies 21 (2): 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/0332331020210209

- Jeffers, G. 2007. Attitudes to Transition Year: A Report to the Department of Education and Science. Maynooth: Education Department, NUI Maynooth.

- Jeffers, G. 2010. “The Role of School Leadership in the Implementation of the TYP in Ireland.” School Leadership & Management 30 (5): 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2010.513179

- Jeffers, G. 2011. “The TYP in Ireland. Embracing and Resisting a Curriculum Innovation.” The Curriculum Journal 22 (1), ISSN 0958-5176. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2011.550788

- Jeffers, G. 2015. TY in Action. Dublin: Liffey Press.

- Johnston, K., C. Conneely, D. Murchan, and B. Tangney. 2012. “Enacting key Skills-Based Curricula in Secondary Education: Lessons from a Technology Mediated, Group-Based Learning Initiative.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education ahead-of-print: 1–20.

- Jones, A. 2004. Review of gap Year Provision. London: Department for Education and Skills.

- Lane, D., O. McGarr, and B. Nicholl. 2023. “Unpacking Secondary School Technology Teachers’ Interpretations and Experiences of Teaching ‘Problem-Solving’.” International Journal of Technology and Design Education 33 (1): 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-022-09731-8.

- Lawlor, J., C. Conneely, E. Oldham, K. Marshall, and B. Tangney. 2018. “Bridge21: Teamwork, Technology, and Learning. A Pragmatic Model for Effective Twenty-First-Century Team-Based Learning.” Technology, Pedagogy and Education 27 (2): 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2017.1405066.

- Marcus-Quinn, A., and T. Hourigan. 2022. “Digital Inclusion and Accessibility Considerations in Digital Teaching and Learning Materials for the Second-Level Classroom.” Irish Educational Studies 41 (1): 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.2022519.

- Marcus-Quinn, A., T. Hourigan, and S. McCoy. 2019. How Should Second-level Schools Respond in an Era of Digital Learning?” In Ireland’s Yearbook of Education 2019/2020. Dublin: Education Matters. https://irelandsyearbookofeducation.ie/irelands-yearbook-of-education-2019-2020/second-level/how-should-second-level-schools-respond-in-an-era-of-digital-learning/

- Martin, A. J. 2010. “Should Students Have a gap Year? Motivation and Performance Factors Relevant to Time out After Completing School.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102 (3): 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019321.

- Mooney, A., J. Duffin, T.J. Naughton, R. Monahan, James F Power, and P. Maguire. 2014. PACT: An initiative to introduce computational thinking to second-level education in Ireland. In: International Conference on Engaging Pedagogy 2014 (ICEP), 5th December 2014, Athlone Institute of Technology.

- Moursund, D. 2002. Project-Based Learning: Using Information Technology 2nd ed. Oregon: International Society for Technology in Education.

- Moynihan, J. 2015. “The Transition Year: A Unique Programme in Irish Education Bridging the Gap Between School and The Workplace.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 8: 219–230.

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). 2021. Digital Learning in Schools: A Roadmap for Enhancement. https://www.ncca.ie/media/4595/digital_learning_in_schools_final.pdf.

- NCCA. 2022. Background paper and brief for the review and revision of the Transition Year Programme Statement - as part of the broader Senior Cycle Redevelopment.

- Ng, K. W., F. McHale, K. Cotter, D. O’Shea, and C. Woods. 2019. “Feasibility Study of the Secondary Level Active School Flag Programme: Study Protocol.” Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 4 (1): 16. MDPI AG. http://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4010016.

- O’Regan, C., B. Brady, and C. Connolly. 2021. Bridging Worlds: New Learning Spaces for new Times: Evaluation Report. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway.

- O’Regan, C., B. Brady, and C. Connolly. 2022. Bridging worlds: new learning spaces for new times (Supplemental report). UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland Galway.

- O’Sullivan, K., N. Bird, and K. Marshall. 2021. “The DreamSpace STEM-21CLD Model as an aid to Inclusion of Pupils with Special Education Needs.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 36 (3): 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1762989.

- O’Sullivan, K., A. McGrane, S. Long, K. Marshall, and M. Maclachlan. 2023. “Using a System Thinking Approach to Understand Teachers’ Perceptions and use of Assistive Technology in the Republic of Ireland.” Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 18 (5): 502–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2021.1878297.

- Papert, S. 1980. Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. New York, NY: Basic Books.