ABSTRACT

This paper explores and compares the experiences and perspectives of primary teachers regarding the teaching of religion in Catholic schools in Ireland and South Korea. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten teachers from each country. The findings highlight the contrasting perspectives of teachers from the two countries regarding the importance of and approach to religious education as a response to the challenges posed by pluralism. Teachers from Ireland predominantly exhibit a proactive approach, valuing diverse viewpoints and making efforts to engage in interreligious dialogue. Conversely, many teachers from South Korea demonstrate a deep appreciation for their own belief in God and prioritise the faith development of children. The comparative study highlights the importance of understanding teachers’ experiences and the ways in which they navigate the intersection of religious diversity, national policies, Catholic ethos, and their own personal faith perspectives. Our findings demonstrate the central role of teachers’ beliefs and future-oriented agency in the construction and implementation of religious education which does not always follow prescribed confessional or secular-neutral approaches.

Introduction

This paper explores and compares teachers’ responses to the demands of teaching religion in Catholic schools in the context of significantly diversified student populations in Ireland and South Korea. Catholic schools, with their specific religious ethos, face the unique challenge of balancing the teaching of religion while ensuring a welcoming and inclusive environment for students from various cultural and religious backgrounds. This paper delves into the perspectives and lived experiences of teachers in navigating this delicate balance.

The unique cultural and historical contexts of Ireland and South Korea provide an intriguing comparative framework for this study. In Ireland, Catholicism has been deeply intertwined with national identity, and Catholic schools follow a Catholic ethos. Despite significant societal shifts and increased calls for more multi-denominational education offerings, the majority of primary schools in Ireland remain under Catholic patronage (Darmody, Tyrell, and Song Citation2011; Faas, Darmody, and Sokolowska Citation2016). In contrast, South Korea is a nation characterised by a much more diverse landscape of religions and belief system with Catholicism representing a minority religion and a small percentage of schools ascribing to the Catholic ethos. By investigating teachers’ perspectives on, and responses to, cultural and religious diversity in these two contrasting contexts, this research aims to explore the nuanced relationships between contextual and personal factors and the pedagogical approaches employed in religious education classes. Findings presented here will shed light on the complexities of teaching religion in Catholic schools with diverse student populations, enriching the ongoing dialogue surrounding essential themes such as religious plurality, religious education (referred to as RE hereafter), and the structural and pedagogical challenges faced by Catholic primary schools in Ireland and Korea.

This article draws on teachers’ experiences, reflections and on some examples of pedagogical approaches regarding the teaching of religion in Catholic schools with culturally and religiously diverse student populations in two different national contexts. It is important to note that the intention of this study is not to evaluate the teachers’ or countries’ success or failure in responding to religious diversity. Rather, the paper seeks to delve into and compare the experiences and perspectives of teachers to enrich the ongoing dialogue surrounding essential themes such as religious plurality, RE, and the structural and pedagogical challenges faced by Catholic primary schools in Ireland and Korea.

The following key research questions guided the empirical study:

What are the experiences of teachers teaching religious education in Catholic schools with diverse student populations in Ireland and South Korea?

In how far, and in what ways, do teachers respond to the presence of students with different religious backgrounds in their teaching of religion in schools with a Catholic ethos?

In how far, and in what ways, do teachers feel that their own faith, or worldview, impacts their teaching of religious education?

The paper continues with the literature review focusing on RE, teachers’ religious backgrounds and their perspectives on teaching religion. It then moves on to describe methodology and findings, followed by a discussion and conclusion.

Context and literature review

Religious landscapes in Ireland and South Korea

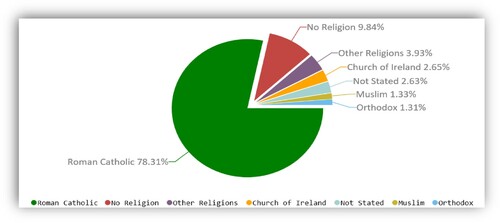

Over the past three decades, Ireland has undergone a remarkable transformation, transitioning from a predominantly Catholic society to an increasingly pluralist and secular one (CSO Citation2017). This shift can be attributed to the substantial influx of immigrants into the country, resulting in the emergence of ethnically and religiously diverse communities. Notably, the non-Catholic population has experienced significant growth, driven not only by a rise in individuals with no religious affiliation but also by the arrival of people practising different faiths. However, despite these changes, Ireland still remains predominantly Catholic, with 78.3 percent of the population identifying as Roman Catholic (CSO Citation2017) ().

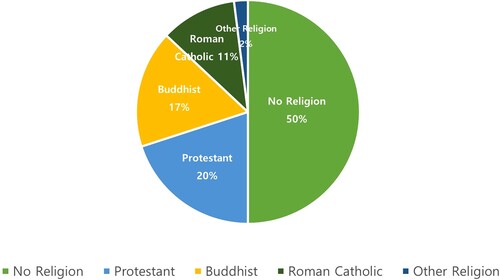

The Republic of South Korea (hereafter referred to as Korea) is a nation characterised by a more diverse landscape of religions and belief systems. Among the prominent faiths practiced in the country are Shamanism, Protestantism, Buddhism, Taoism, Catholicism, Confucianism, Islam, and various new religions. According to the 2021 national census (Lee Citation2021), a significant portion of the Korean population, 50 percent, identified themselves as having ‘no religion’. Furthermore, the census indicated that 20 percent of the population identified as Protestants, while 17 percent identified as Buddhists, and 11 percent as Catholics ().

A significant characteristic of Korea’s diverse belief traditions is that various religions have maintained a great influence on society. Kim (Citation2007) argues that the multi-religious situation of Korea is unusual, in the sense that both eastern and western religions co-exist without any one particular religion taking precedence over another, offering people a view of different religions and new worldviews.

Religious education and religion/s in school contexts in Ireland and South Korea

The presence of minority belief pupils and pupils with no religious affiliation poses a significant challenge for the predominantly denominational Irish school system. Currently, an overwhelming majority of primary schools in Ireland, accounting for 96.4 percent, operate under the patronage of the Catholic Church and the Church of Ireland. In contrast, only 3.6 percent of schools follow a multi-denominational approach, being under the patronage of organisations such as Educate Together, An Foras Pátrúnachta, and Community National Schools (DES Citation2017). The expanding sector of multi-denominational primary schools has a significant impact on the overall educational system, challenging established notions of the role of religious education (RE) and requiring adjustments to effectively address the religious and educational needs of all children (Kieran and Hession Citation2005). The Catholic Primary Schools Management Association (CPSMA Citation2017) has indicated that the religious values and practices of school ethos are considered to permeate the very fabric of school life. In this context, Darmody and Smyth (Citation2016) question how religious difference is respected in denominational schools.

In Ireland, Catholic schools are faith-based schools which reflect the guidelines issued by the Irish Episcopal Conference (IEC), together with Catholic theology and a Catholic philosophy of education. IEC (Citation2015, 25) specifies in its framework that ‘the mystery of God – Father, Son and Holy Spirit – is the centre of the curriculum’. It also states that those delivering the curriculum as a divine pedagogy should ‘remain faithful to God’s Revelation and Church teaching must be presented in its fullness, not fragmented or impoverished’ (IEC Citation2015, 25). Researchers have raised concerns regarding the in/compatibility of the requirements of Catholic primary schools with the backgrounds and perspectives of a significant proportion of primary teachers in an increasingly diverse and secular society (Heinz, Davison, and Keane Citation2018). Heinz, Davison, and Keane (Citation2018) found that while a significant proportion of primary ITE applicants appreciated the importance of ‘passing on Catholic values and beliefs’, approximately one third rarely or never practiced their religion and many preferred to teach religion using a non-confessional model.

In Korea, religious freedom and basic law of education were constitutionally declared in the second half of the twentieth century. The current Korean constitution stipulates that ‘All the people should have the freedom of religion. The establishment should not be allowed and religion should be separated from the state’ (Article 20). The principle of education is also codified, stating that ‘public schools established by the state or the local self-government should not give religious education for a particular religion’ (Article 6). Many scholars link secularisation to the country's history of tensions and conflicts (Kim Citation2007). However, in education contexts, a non-confessional model of religious education has also been linked to the intention to facilitate a holistic understanding of religion beyond the education of a particular religious view. RE should, therefore, aim to teach religion as an object of academic inquiry that is integrated across secular subject areas such as history, ethics, society and culture (Kim Citation2007). Cho (Citation2016) claims that ‘mixed views’ on religious pluralism promote an ‘academic understanding of Korea’s indigenous religions and multi-religious context’. However, having considered the multi-faceted nature of children’s spiritual and religious development, Kim (Citation2018) argues that the framework of a strict non-confessional academic perspective does not sufficiently meet the requirements that belong to a proper understanding of RE resulting in the emergence of ‘a type of barren and dangerous secularist response that tends to ignore RE and a school’s foundational spirit altogether’ (Kim Citation2018, 12). Currently, religiously founded schools account for 20 percent of all schools in South Korea (Kim Citation2018). Among them, Catholic primary and secondary schools number almost 65 schools (Kim Citation2016).

The government-controlled system places limitations on the implementation of RE and the freedom of RE rights in faith-based schools (Kim Citation2018). Denominational schools and teachers describe the RE curriculum guide as ‘too intrusive’ and complain about not being allowed to teach their own religion freely (Jung Citation2001). According to Kim (Citation2018), most of the religiously founded schools try to introduce their own form of RE in an independent way, using extracurricular activities within the context of the national curriculum.

Teachers’ religious backgrounds and their perspectives on teaching religion

Pohan and Aguilar (Citation2001) argue that ‘educators’ beliefs serve as filters for their knowledge bases and will ultimately affect their actions’ (160). Hartwick’s research showed that teachers who had a strong religious background tended to understand the purpose of teaching religion as the transmission of faith, which, in turn, nurtured a hierarchical relationship with knowledge and authority (Hartwick Citation2015). However, as society has become increasingly pluralist, studies focusing on teachers’ views of religion have emphasised the importance of teaching about different religious viewpoints and of the teacher’s role to provide accurate information including in relation to secular humanism and other non-religious philosophies (Darmody and Smyth Citation2016; Jackson Citation2012). Mcgrady (Citation2013) points out that there is appreciation among teachers for the type of scientific thinking exercised by both the human sciences and the sciences of religion in RE which assists in expanding the horizon for addressing religion. However, studies in Ireland have shown that some teachers struggle to overcome the distance that has emerged between the faith formation element of the Catholic tradition and the attitude of secularised contemporary society (Heinz Citation2013; Irwin Citation2017; Mcguckin et al. Citation2014). Recent proposals set out in Irish primary education also present difficulties in addressing such plurality, in terms of both the particularity of the ethos of the school and the diverse nature of classrooms and inclusion policies for schools (NCCA Citation2015, Citation2020).

Methodology

This study has used Bråten’s model for comparative studies in RE (Bråten Citation2015) as a framework for design and data analysis. Bråten’s model identifies three contextual dimensions, the supranational (international), national (country-wide), and subnational (regional) dimension, as well as four levels of curriculum development and enactment, societal, institutional, instructional, and experiential (Bråten Citation2015). The societal level represents the political and the professional debates about RE. The institutional level is the curriculum derived from the societal level, but specified by the state and modified by the school. In Ireland, relevant expressions include the Catholic Preschool and Primary School Religious Education Curriculum, National Council for Curriculum and Assessment for RE. In Korea the institutional level includes National Curriculum and Regional Guidelines, and the Korean Constitution. The institutional level of curriculum includes legislation regarding the place of RE and curriculum documents. The instructional level relates to how teachers deliver the curriculum in the classroom. Finally, the experiential level is grounded in the experiences and perspectives of the children. It is the curriculum as it is internalised and made personal, i.e. how pupils relate to religion, and what they learn about and from religion (Bråten Citation2013). In this paper, the focus of the experiential level is shifted as we explore teachers’ personal experiences, concerns and convictions. The combination of these factors in our comparative analysis allows us to capture some of the complexities of what goes on in each country while at the same time considering the impact of supranational processes (Bråten Citation2013). In our analysis, we pay special attention to how supranational challenges related to increasingly diverse student populations are experienced differently and result in different responses by teachers in Irish and Korean schools.

Purposive sampling was used to recruit ten participants from each country. All participants were teachers in Catholic primary schools catering for pupils from various nationalities and religious backgrounds. Interviews took place between September 2021 and April 2022. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the University. The interview schedule was developed based on literature review and piloted with four teachers in Ireland and three teachers in Korea. Of the twenty interviews, thirteen were conducted face to face and seven online. It is often challenging to conduct long distance case studies, the COVID-19 pandemic added further difficulties with interviews for much of 2021. Interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes. They were conducted in English with teachers in Ireland and in Korean with teachers in Korea. All interviews were recorded and later transcribed. Translation from Korean to English was reviewed by the bilingual researcher. To protect participants’ anonymity, pseudonyms are used throughout the findings section.

The qualitative software NVivo 12 was used for data coding following Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006, Citation2019) six-step thematic analysis: ‘familiarisation with the data; generation of initial codes; searching for themes; reviewing themes; defining and naming themes; producing the report’. Throughout the data analysis process, the researcher searched for and reflected on concepts, patterns and themes across the data to ‘discover variation, portray shades of meaning, and examine complexity’ (Rubin and Rubin Citation2005, 202). Both, the Irish and Korean data sets were, initially, analysed separately. Some 1,150 codes were created across ninety categories, which were then placed in pattern codes and concepts. As codes and themes emerged during the analysis, they were contextually compared and integrated. Three main themes will be explored in this paper: (i) teachers’ commitment and efforts to build appreciation and understanding of different religions in Ireland, (ii) appreciation and commitment to upholding the Catholic ethos while valuing and respecting diversity in Korean schools, and (iii) teachers’ views regarding the impact of their ‘faith’ on their teaching of religion.

Findings

Teachers’ commitment and efforts to build appreciation and understanding of different religions in Ireland

Whilst all schools in this research were under Catholic patronage, children who were pupils in these Catholic schools came from a variety of religious and cultural backgrounds, and this was particularly evident in the Irish school setting. Most of the Irish teachers were very aware of those of minority beliefs within the class. Some participants said that the acknowledgement of the diverse voices and learning about the children’s backgrounds was something that they prioritised in their teaching.

It’s my duty, in a respectful way. Not in a tell me everything about you way because I’m curious. No, I want to attend to the child’s needs properly. I want to make them feel a part of this school community. I feel I can do that best if I know what is important to you in terms of beliefs and culture. If I don’t know that, I could step over, cross a boundary or miss something or disrespect the child in a completely innocent way. (Jessica)

I’m very interested in it. We’re very engaged with other people’s religions. I’d love to sit down and read a book about different religions and everything like that. It would be something that I get to know their own background and their religious identity … (Nicola)

There are 30 children in my class. We have 28 non-national children and two Irish children, actually the two Irish are siblings. They’re brother and sister. And about 18 of them are Polish and the other 10 non-nationals are Russian, Romanian, African. I may be missing some there … That will be a big part of my own identity as a teacher, getting to know children’s culture and children’s religious identity. (Tom)

As a teacher […] sometimes we might give a story that interferes with the other person’s religious beliefs. I, a teacher may not have thought of that in preparing my lesson. It just may not have entered my head. When you go to introduce it, it becomes … I can’t do that. You have to adjust and you have to be constantly aware of the other kids within your class that are not Catholic. They can’t participate in certain stuff … Just to clear the air before. I would always have felt I would be conscious of clearing the air. (Margaret)

Actually, they don’t believe that other people can intercede for you, you must pray directly to God. At least I had that knowledge … culturally, what is different for them? Or what is applicable? And what is not? … they come with a story. They’re not blank canvases when they get to you. They don’t switch off their identity at nine o’clock in the morning. (Tom)

I had a Jehovah’s Witnesses. They don’t do Halloween. They don’t do Christmas. They don’t do birthdays. It made all children find very hard to understand why you wouldn’t celebrate your birthday. Why you wouldn’t have Christmas? Why you don’t have Santa? That can cause a little bit of a confusion with the kids that believe one thing while the other children don’t. (Margaret)

Another teacher, Michael, also emphasises the importance of learning and understanding which can ‘breed tolerance even if it’s only a little bit of understanding’. His desire to embrace the belief traditions of others, alongside Catholic belief traditions, prompts him to suggest that ‘we can fit the church calendar around pagan festivals’. When asked what he meant, he replied:

I would have explained to the class to the best of my knowledge … Easter is not the same time every year. It moves a bit. We celebrate Christmas on the same date. Then if you look at the church calendar, you give them credit for being, not complicating things, by basically looking at the pagan festivals. We can fit the church calendar around pagan festivals that they had been used to celebrating and similar times of year. (Michael)

as a school staff, I just have to be very sensitive to the family [of other religious traditions] and try as best as I can to incorporate within the school day … allowing the child to share their experience of their religion with the rest of the class.

Appreciation and commitment to upholding the Catholic ethos while valuing and respecting diversity in Korean schools

The data collected in Korea demonstrates that teachers support the children in exploring their Catholic ethos and focus more on creating a supportive environment within the Catholic tradition. The ‘Gospel spirit’ is particularly evident throughout the interviews with Korean teachers. It appears that their religious devotion and religious way of life permeate the entire school day. Most Korean teachers acknowledge the importance of school assemblies and of displays of religious objects such as rosary beads, religious statues and holy water in their classroom and school.

I’d have a religious area in the classroom, where I would have a little altar, maybe with the Holy Family, and maybe the Trinity. I have a little candle there as well. I’d usually have rosary beads there so that we could talk about the Rosary and make it normal to say the Rosary. Because that’s something that probably isn’t happening in houses. (Sungje)

We would have had a space in the school where there was a different part of the year, different features like for the month of May. We might have had a display for Our Lady, looking at the different prayers associated with Our Lady. It would be in a central spot so that the children will be able to engage with it outside of the classroom too. We would have had a prayer at the start of our weekly meetings where we would have some time to reflect and think about our own faith and our own religious identity. (Minsu)

We have multi-faith and multi-cultural events in the school where we celebrate differences and we explore what other celebrations are going on at different times. We’re looking at Buddhism, Confucianism and indigenous beliefs as well as cultural, shamanic traditions derived from certain religious practices. (Susin)

Maybe have the displays of different culture that are relevant in the class, where different people come from and to recognize our cultures also … It could be celebrated maybe in the school newsletter, whatever the religion or culture is. We celebrate the values we share in the school and this enhances the relationships in the class. (Jina)

A Catholic school helps them to see this beautiful world that God has given to us to be carers of this beautiful art. (Jina)

I am a Catholic teacher in a Catholic school educating in the Catholic faith, while giving children of different faith and no faith, space to be who they are … Teaching within the Catholic ethos means that it is my responsibility to educate children in the Catholic faith. At the same time, I am integrating the shared values of a diverse classroom throughout the day. (Changju)

Teachers’ views regarding the impact of their own ‘faith’ on their teaching of religion

An important theme emerging from the analysis was the ‘teachers’ own faith’ and its influence on their approach to teaching religion in a Catholic school. Some of the Korean participants spoke at length about the importance of teachers’ religious identity and faith. Although this theme also emerged in a few interviews with Irish teachers, it was particularly prominent and accompanied by more elaborate reflections within the Korean context. Susin, a teacher from Korea, feels strongly about the importance for teachers to have a strong Catholic faith.

I do think that having a solid grounding, having a good idea of your own identity and your own faith does impact the way that you teach it … We need to be Catholic and that’s our identity, you need to step into it more. (Susin)

One of the things that I think are really important is that, as a Catholic, we believe that we’re receiving the body and blood of Christ. We can be a lot better and more open about expressing our faith and our belief. That’s my view of religious education, that we’re following the program that could be a little bit stronger on the teachings of the church in Catholic schools in particular. Perhaps we could be a little bit stronger. I think it’s important that we are strong. (Susin)

I’m strong on my own faith. So I know that I’m going to be able to carry that and I do know that I had a relationship with God. I will be strong enough in what I believe as an educator. (Kiyun)

Because the person who teaches RE is now a nun, there are other influences on some students from that. I think it has a more educational effect, rather than just taking RE as a general subject. My identity is a Catholic nun, and I’m trying to play a role as a nun here in public education … I think they should be exposed to it in school … I suppose they know they’re learning about God and Jesus and maybe when they’re a bit older, they might speak more about the fact they are fully committed Catholics. (Kiyun)

In Ireland, Ciara identifies as a strongly affiliated Christian, ‘I am a strong believer in Jesus and God’. She feels that teachers should be comfortable and confident to talk about their own beliefs, traditions and the content of faith, suggesting that ‘I really think a big part of it is the teachers’ familiarity and how comfortable they are with teaching religious education’. For this reason, she raises concerns about the experiences of non-Catholic teachers teaching in Catholic schools:

I know I have a friend who is a teacher, who is an atheist, and teaches in the Catholic school. She finds it uncomfortable to talk about God and especially if there is a question relating to life and death, and questions that come from the Bible that are difficult to answer. So she finds it uncomfortable, and I had that discussion with her recently. And she’s a bit awkward. (Ciara)

I think one of the biggest ones is how comfortable the teacher is with their own religious identity and how comfortable they are in teaching religious education in the school in the classroom. From my own experience, for me it’s something I love to teach, something I love engaging with students. I know that there are other teachers in the school who are not comfortable, because they just don’t have a strong sense of their own spirituality or identity when it comes to religion and spirituality. It’s probably a little bit uncomfortable to be talking about Jesus and God if you’re not a believer. But I don’t think you have to be a believer to do it. (Daniel)

Discussion

This paper explored the perspectives and experiences of teachers in relation to teaching religion in Irish and Korean Catholic primary schools with increasingly diverse student populations. The findings demonstrate both unique as well as common experiences and perspectives in the two distinct national contexts. What is obvious from the data analysis is that most of the participants generally have positive experiences and attitudes towards teaching RE as well as towards diversity and welcome students from different cultural and religious backgrounds in Catholic ethos schools. However, clear differences have emerged from the analysis with regard to teachers’ perspectives about the importance of faith formation, with teachers from Korea, all of whom were Catholic priests and nuns, demonstrating a much stronger commitment to the development of their students’ religious and spiritual character. Indeed, some of the participants from Korea describe teaching as a vocation, something that helps them cultivate children’s Catholic faith and shape their religious identity. It also appears that teachers from Korea tend to adopt a catechetical framework that promotes students’ faith formation and, in doing so, dedicate themselves to the transmission of Christianity. For them, the promotion of understanding of God and the Catholic faith seems to be a priority, as opposed to the direction of the Korean government’s educational policy guidelines calling for a neutral-secular RE and a focus on religious plurality (Korean Ministry of Education Citation2015; Article 20 of the Constitution of S. Korea).

In contrast, the teacher participants from Ireland, who do not belong to religious orders and vary in the existence and/or strength of their Catholic faith, demonstrate a stronger focus on cultural and religious diversity as a significant issue within their teaching. They exhibited a greater awareness of different religions in their schools, likely due to the number of students from diverse backgrounds enrolled in Catholic schools in Ireland surpassing those in Korea. The data collected provides strong evidence of Irish teachers’ profound interest in world religions and their commitment to interreligious engagement. Their appreciation of the importance of interreligious understanding and engagement align with the vision of inclusive education portrayed in Irish policy documents (IEC Citation2015; National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) Citation1999, Citation2020, Citation2015; Department of Education and Science, Primary School Curriculum (DES PSC) Citation1999) even though their experiences also demonstrated difficulties in translating inclusive approaches into practice. Irish teachers’ desire to better understand and incorporate the diverse experiences of their students align strongly with Jackson’s (Citation2004) perspective, which emphasises the importance of children learning about other faith traditions to foster understanding and tolerance.

It is particularly interesting to note that teachers in Irish Catholic schools expressed greater caution with regard to a confessional approach to RE, which is explicitly promoted by the Irish Episcopal Conference (Citation2015), highlighting their concerns about potential confrontations or misunderstandings in the classroom as well as discomfort it can cause for non-religious colleagues. The latter concern has also been raised by Heinz, Davison, and Keane (Citation2018) in their study exploring the religious backgrounds and perspectives on teaching religion of primary teacher education entrants. In this study the researchers found less than half of student teachers agreed with teaching religion as part of their teaching role with many portraying compliant rather than positive attitudes towards RE in primary schools. Drawing on these findings, the researchers argue that the prescribed confessional approach which applies to the great majority of primary schools in Ireland may cause significant conflict between teachers’ personal beliefs and expected professional practice (Heinz, Davison, and Keane Citation2018).

Nevertheless, despite the observed differences regarding the shared understandings within the two national contexts, the integrated analysis of the data from both contexts also shows that teachers with strong religious affiliations are, in both contexts, more interested in facilitating children in the development of their religious identity. Additionally, those who self-identify as being very religious place greater emphasis on their commitments and the transmission of the Catholic faith tradition.

Applying the supranational, instructional and experiential comparative lenses (Bråten Citation2015) in the interpretation of our findings highlights the central role of teacher agency within the context of contemporary RE. It is clear from both data sets that teachers are responding to supranational developments, especially to the diversification of student populations as well as international initiatives that emphasise inclusive education policies and practices (Jackson Citation2014). However, our data also demonstrate that the approaches of many teachers to the teaching of RE, in either a confessional or non-confessional way, may deviate from national policy (in the case of Korea where a secular approach is prescribed) or from national curricular guidelines (in the case of Ireland where faith formation forms a key focus of RE in Catholic primary education). Biesta, Priestley, and Robinson (Citation2015) suggest that teachers’ beliefs about teaching and about educational purpose inform teachers’ perceptions, judgements and decision-making, motivating their actions. Our findings reflect this connection demonstrating how teachers’ own religious beliefs and/or worldviews influence their beliefs about the purpose of RE in Catholic primary schools which, in turn, drive their pedagogical approaches. Our research furthermore indicates that teachers’ personal beliefs and experiences in the classroom take central stage as they critically engage with competing faith and secular viewpoints. Rather than a mere understanding and compliant implementation of current policy and/or school ethos, teacher agency within the specific context of RE appears to be influenced heavily by the teachers’ personal religious values and/or worldviews.

Limitations

Due to the relatively small sample size, the experiences shared by the participants of this study may not reflect the experiences of other teachers in Ireland and Korea. Additional studies with larger sample sizes may be beneficial to further explore perspectives and experiences of teachers and to test the generalizability of the findings from this study.

Conclusion

This paper explored the perspectives and experiences of teachers in Irish and Korean Catholic primary schools as they navigate the increasingly diverse landscape of their student populations. The research findings unveiled complex layers of diversity, policy and teacher agency. The majority of participants, regardless of their backgrounds and the national education contexts, held positive attitudes towards teaching Religious Education (RE) and welcomed the presence of students from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds in Catholic ethos schools. However, an interesting contrast emerged with regard to the emphasis placed by the teachers on faith formation as a goal of RE. Korean teachers, predominantly Catholic priests and nuns, exhibited a deep commitment to nurturing their students’ religious and spiritual character. They saw teaching as a vocation, a means to cultivate children’s Catholic faith, and shape their religious identity. In contrast, Irish teachers, who varied in their personal religious beliefs and affiliations, demonstrated a heightened focus on cultural and religious diversity as a central issue within their teaching. Nevertheless, regardless of their national context, those who self-identified as very religious, which included a small number of teachers from Ireland, placed a greater emphasis on their commitments to the transmission of the Catholic faith tradition.

The differences in teachers’ perspectives and practices are particularly interesting when we consider how approaches to RE deviate from legal and policy frameworks in each national context. In Ireland, Catholic schools are permitted by law to follow a denominational religious curriculum, which places faith formation at the core of RE. However, the affiliation of teachers with the Catholic faith, or with other worldviews, varies significantly, with an increasing number feeling uncomfortable teaching in a manner contrary to their beliefs. This has fuelled a strong desire among Irish educators to provide a more open religious education curriculum, with a focus on exploring a wide range of world religions.

In contrast, the Korean government prescribes a neutral approach to religious education, reflecting the nation’s diverse religious landscape where Catholicism represents a minority religion. In this context, only a small number of Catholic schools exist, staffed primarily by Catholic nuns and priests who, also, tend to deviate from national policy to adhere to and enact their own beliefs and missions.

This study, thus, underscores the significance of teacher agency within the realm of contemporary RE. Teachers in both contexts are responding to supranational developments, such as the diversification of student populations and international initiatives promoting inclusive education. However, their approaches to teaching RE may deviate from national policies or curricular guidelines aligning, instead, more closely with their own beliefs and visions for RE which are, in turn, strongly influenced by their personal religious faiths and/or worldviews.

At a time where RE is increasingly challenged to relate to plurality and secularisation across the world, comparative research can provide new insights and prompt deeper conversations about the complex interactions, and tensions, between the expectations and practices of different actors. Considering the challenges teachers face as they navigate the complexities of diversity, studies exploring the experiences and expectations of children and their families can make an important contribution to discussions about the future of RE in Catholic as well as in other faith-based schools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jinmin Cho

Jinmin Cho is a PhD Researcher in the School of Education at the University of Galway. Her academic interests focus on religious education in Ireland and South Korea, diversity of religion and culture, inclusion, children’s religious and spiritual development, and comparative case studies.

Manuela Heinz

Manuela Heinz is an Associate Professor and Head of Discipline of Education at the University of Galway. She has published widely on the topics of diversity, inclusion and teacher professional learning and is a member of the Editorial Board of the European Journal of Teacher Education.

Jungui Choi

Jungui Choi is a Professor, Head of the Graduate School of Education at the Catholic University of Korea, and a priest of the Catholic Archdiocese of Seoul, South Korea. His academic interests focus on Catholic identity, spirituality, Catholic school, religious education, and curriculum design and development.

References

- Biesta, Gert, Mark Priestley, and Sarah Robinson. 2015. “The Role of Beliefs in Teacher Agency.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 624–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325.

- Bråten, Oddrun Marie Hovde. 2013. Towards a Methodology for Comparative Studies in RE: A Study of England and Norway. Münster: Waxman Verlag.

- Bråten, Oddrun Marie Hovde. 2015. “Three Dimensions and Four Levels: Towards a Methodology for Comparative Religious Education.” British Journal of Religious Education 37 (2): 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2014.991275.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676x.2019.1628806.

- CPSMA (Catholic Primary School Management Association). 2017. Submission to the NCCA Consultation on Time and Structure in a Primary Curriculum. https://www.ncca.ie/media/3234/writtensubmissionsdocument_structureandtime_ncca.pdf.

- Central Statistics Office. 2017. Census 2016 Summary Results. Dublin: CSO. Accessed June 12, 2023.

- Cho, Kyuhoon. 2016. “Protestantism, Education, and the Nation: The Shifting Location of Protestant Schools in Modern Korea.” Acta Koreana 19 (1): 99–131. https://doi.org/10.18399/acta.2016.19.1.004.

- Darmody, Merike, and Emer Smyth. 2016. Education about Religions and Beliefs (ERB) and Ethics: Views of Teachers, Parents and the General Public Regarding the Proposed Curriculum for Primary Schools. Dublin: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

- Darmody, Merike, N. Tyrell, and S. Song. 2011. The Changing Faces of Ireland: Exploring the Lives of Immigrant and Ethnic Minority Children. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- DES (Department of Education). 2017. Department of Education and Skills Annual Report.

- DES PSC (Department of Education and Science, Primary School Curriculum). 1999. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

- Faas, Daniel, Merike Darmody, and Beata Sokolowska. 2016. “Religious Diversity in Primary Schools: Reflections from the Republic of Ireland.” British Journal of Religious Education 38 (1): 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2015.1025700.

- Hartwick, James M. M. 2015. “Public School Teachers’ Beliefs in and Conceptions of God: What Teachers Believe, and Why It Matters.” Religion & Education 42 (2): 122–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/15507394.2014.944065.

- Heinz, Manuela. 2013. “The Next Generation of Teachers: An Investigation of Second-Level Student Teachers’ Backgrounds in the Republic of Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies 32 (2): 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2012.747737.

- Heinz, Manuela, Kevin Davison, and Elaine Keane. 2018. “‘I Will Do It but Religion Is a Very Personal Thing’: Teacher Education Applicants’ Attitudes towards Teaching Religion in Ireland.” European Journal of Teacher Education 41 (2): 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2018.1426566.

- Irish Episcopal Conference. 2015. Catholic Preschool and Primary Religious Education Curriculum for Ireland. Dublin: Veritas.

- Irwin, Jones. 2017. “Existential Thought between Ethics and Religion as Related to Curriculum: From Kierkegaard to Sartre.” In Does Religious Education Matter?, 1st ed., edited by Mary Shanahan, 184–193. New York: Routledge.

- Jackson, Robert. 2004. “Intercultural Education and Religious Diversity: Interpretive and Dialogical Approaches from England.” In The Religious Dimension of Intercultural Education, edited by Council of Europ Publishing, 39–50.

- Jackson, Robert. 2012. “The Interpretative Approach to Religious Education: Challenging Thompson’s Interpretation.” Journal of Beliefs & Values 33 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2012.650024.

- Jackson, Robert. 2014. Signposts – Policy and Practice for Teaching about Religions and Non-Religious World Views in Intercultural Education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Jung, Chin Hong. 2001. “The 7th Curriculum Revision and Teaching Religion.” Korean Journal of Religious Education 13: 3–42.

- Kieran, Patricia, and Anne Hession. 2005. Children, Catholicism and Religious Education. Dublin: Veritas.

- Kim, Chong Suh. 2007. “Contemporary Religious Conflicts and Religious Education in the Republic of Korea.” British Journal of Religious Education 29 (1): 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200601037486.

- Kim, Chong-Suh. 2016. “The Development of Religious Education and Its Implications for ‘Education of Humanism’.” Literature and Religion 21 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.14376/lar.2016.21.1.01.

- Kim, Chae Young. 2018. “A Critical Evaluation of Religious Education in Korea.” Religions 9 (11): 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9110369.

- Lee, D. H. 2021. “[2021 Religious Perceptions Survey] Religious Population and Religious Activity.” The Hankook Research. Last Modified December 8. https://hrcopinion.co.kr/archives/20186.

- Mcgrady, Andrew. 2013. Teaching Religion: Challenges and Opportunities for Educational Practice in a Pluralist Context. Edited by Gareth Bynre and P. Kieran. Dublin: The Columba Press.

- Mcguckin, Conor, C. Lewis, S. Cruise, and J.-P. Sheridan. 2014. “The Religious Socialisation of Young People in Ireland.” In Education Matters: Readings in Pastoral Care for School Chaplains, Guidance Counsellors and Teachers, 228–245. Dublin: Veritas.

- Ministry of Education. 2015. The National Curriculum of Social Studies. http://ncic.go.kr/english.kri.org.inventoryList.do#.

- NCCA (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment). 1999. Primary School Curriculum. http://www.curriculumonline.ie/Primary/Curriculum.

- NCCA. 2015. Education about Religions and Beliefs (ERB) and Ethics in the Primary School: Consultation Paper [Online]. NCCA Website: NCCA. https://ncca.ie/media/1897/consultation_erbe.pdf.

- NCCA. 2020. Draft Primary Curriculum Framework: For Consultation [Online]. NCCA Website: NCCA. https://ncca.ie/media/4870/en-primary-curriculum-framework-dec-2020.pdf.

- Pohan, Cathy A., and Teresita E. Aguilar. 2001. “Measuring Educators’ Beliefs about Diversity in Personal and Professional Contexts.” American Educational Research Journal 38 (1): 159–182. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038001159.

- Rubin, Herbert J., and Irene S. Rubin. 2005. Qualitative Interviewing – The Art of Hearing Data. London: Sage.