ABSTRACT

Based on quantitative and qualitative data and analyses, this article highlights how research in the discipline of history in Sweden has been affected by imperatives of internationalization in recent decades. Four central dimensions of the internationalization of research are discussed in some depth, based on empirically observable changes in the discipline since 2000: (i) geographical areas of research, (ii) international publications, (iii) international researcher mobility, and (iv) international research funding. It is concluded that for the first two dimensions there has been a significant shift towards more internationalization of research in the Swedish discipline of history since 2000, and particularly since 2010, but for the latter two, internationalization is less prominent, even though the opportunities for international mobility and securing international research funding have increased significantly since 2000. The article also highlights some controversies and debates pertaining to the internationalization of historical research in Sweden and the other Nordic countries. It is concluded that Swedish historians have come a long way in overcoming the methodological nationalism that characterized the discipline for most of the twentieth century, and that they now participate more than ever before on the international frontlines of historical research.

Internationalization and methodological nationalism

When it comes to academic research, both internationalization and methodological nationalism are contested, multidimensional concepts. Perhaps all research – including in the discipline of history – is intrinsically international.Footnote1 In that vein, the doyen of Swedish historiography, Rolf Torstendahl, has argued there has hardly ever been a strand of history free of the influence of what people in other countries have thought or written. For Sweden’s part, he highlights how international influences can be traced over more than a millennium, starting with the earliest form of rudimentary written history in Scandinavia, the rune stones.Footnote2

However, despite such influences, research in history and other parts of the humanities and social sciences have sometimes been criticized for being too nationally oriented. Since the end of the twentieth century, particularly since Sweden joined the European Union in 1995, there has been an increased emphasis on internationalization of research and higher education, including aspects such as mobility, networks, publications, research funding, and research themes. The main arguments for the internationalization of research have been that its perspectives are necessary for understanding an increasing globalized world and that it improves the quality, impact, and efficiency of research.Footnote3

Most historians would probably agree that internationalization in the first sense – of being open to influences and new ideas from abroad – is desirable in principle, and generally has a positive effect on the quality of research. However, in other respects, such as when internationalization is taken to mean a greater emphasis on international publications or citations, the recruitment of PhD students or researchers in open international competition, or research about geographically distant parts of the world, there is less consensus about the desirability of internationalization. Against this background, many nationally (but not necessarily nationalistically) oriented researchers in the humanities and social sciences in Sweden and elsewhere have resisted the imperative to internationalize their research.Footnote4

The resistance to internationalization among historians and other researchers in the humanities and social sciences may be linked to the second concept under scrutiny here: methodological nationalism. Since the nineteenth century, empirical studies in the discipline of history have generally been limited to a specific geographical area, primarily defined by the nation-state. There may be compelling reasons for such restrictions, with respect to both the historical importance of the nation-state and its institutions and the need for empirical in-depth studies. However, methodological nationalism entails more than just empirically limiting historical investigations to the nation-state. Above all, methodological nationalism means that historical explanations tend to be national, ignoring or downplaying transnational and other exogenous factors. Historical narratives and interpretations are thus structured beforehand by national perspectives, limitations, sources, concepts, and categories. Methodological nationalism also involves a tendency to see the history of each country as unique, and quite distinct from developments in other countries or regions in the world.Footnote5

Methodological nationalism is by no means limited to Sweden, nor to the discipline of history. Internationally, the concept began to be used in the 1970s in the social sciences, and the debate has since intensified, particularly since around 2000, against the backdrop of the growing importance of transnational and global processes.Footnote6 In Norway, the concept prompted a debate in the wake of an evaluation of the discipline of history commissioned by the Norwegian Research Council and published in 2008. The report, entitled ‘Beyond the nation in time and space’, concluded that the bulk of the historical research in Norway, as elsewhere, was characterized by methodological nationalism. The commission – which consisted of five senior historians from Denmark, Finland, and Sweden – also concluded there was an ‘under-exploited potential in Norwegian professional historical research’ and called for ‘a focused problematization of temporal and spatial borders under reflection on the connections between continuities and discontinuities and on the complex connections between local, regional, national, international, and global borders’.Footnote7

Methodological nationalism was an integral part of the discipline of history from the outset. History first emerged as a modern academic discipline in Sweden, as in other countries, as part of a state-led nation-building project in the nineteenth century. Historians’ main interest was the genealogy of the nation-state and the long historical processes that had led to the emergence of nations, understood in best Hegelian fashion as cultural, linguistic, and spiritual communities. National archives and other vernacular sources were the building blocks of national historiographies, and few historians ventured to study the manuscript sources of other nations, particularly when doing so required proficiency in foreign languages. History also took on a prominent role as a school subject and in the public sphere, which also served the purpose of nation-building – and in some respects continues to do so today in Sweden and elsewhere.Footnote8

In the Nordic countries the emphasis on national history was mitigated to some extent by the long-standing close historical ties, socially, economically, politically, and culturally, between the Nordic countries. These historical circumstances, paired with many historians’ Scandinavist bent, particularly in Denmark and southern Sweden, prompted Nordic historians to take considerable interest in the history of their neighbours, particularly after the turn of the twentieth century. Several initiatives were taken to encourage collaborations, and in 1905 the first Meeting of Nordic Historians (Nordiska historikermötet) was held in Lund in southern Sweden. The establishment in 1928 of the Lund-based journal Scandia, with its openly Scandinavian focus, in contrast to the older, more nationally oriented Historisk Tidskrift, further stimulated Nordic collaborations to integrate the study of the region’s history. Nordic collaboration gained further in strength after the Second World War; the founding in 1976 of the Scandinavian Journal of History by the historical associations of the five Nordic countries was a demonstration of Nordic historians’ collaborative efforts.Footnote9

The focus on national and regional frames of study in Nordic historiography, however, meant that few Nordic historians before the mid twentieth century ventured outside the region to study the history of other countries or cultures. In the second half of the twentieth century, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a surge in interest in international history, but for the most part the discipline of history in Sweden continued with its strong focus on the nation’s history for its own sake, rather than as part of broader, international, or universal historical processes. The situation was similar in Denmark and Norway, but in Finland the strict division between Finnish or Nordic history and general history led both to a stronger insulation of the former from global and transnational historiographic trends, and to a waxing and waning in the relative strengths of the two disciplines throughout the twentieth century.Footnote10

Against this background, this article explores how Swedish historians have dealt with the trend towards the internationalization of research since 2000. Based on quantitative and qualitative data, it analyses several of the key aspects of the internationalization of historical research in Sweden since the early 2000s. The study also introduces some debates and controversies about various aspects of the internationalization of historical research in Sweden, including international rankings, bibliometric measures, and the use of English – as opposed to Swedish – for academic publishing and other forms of research communication.

First, a caveat about the scope and validity of the study. It is limited to the internationalization of historical research since 2000 and does not discuss the parallel internationalization of higher education.Footnote11 It is also limited to the discipline of history proper, and does not extend to neighbouring disciplines such as economic history and the history of science and ideas, both of which are strong disciplines in their own right in Sweden. The impression is that the two neighbouring disciplines are in several respects more international and less troubled by methodological nationalism than the discipline of history. The effect of this typically Swedish division of historical studies into three separate disciplines may have contributed to the past tendency towards methodological nationalism, because of a dynamic similar to the one described by Max Engman in the Finnish distinctions between national and Nordic history on the one hand and general (or universal) history on the other.Footnote12

The aim here is introduce an international audience interested in Swedish and Scandinavian historiography, and its place in cutting-edge historical research, to the historiographical developments and debates about internationalization and methodological nationalism in Sweden. It is also a response to recent calls for more empirical research about the internationalization of research, which has attracted far less attention than the internationalization of higher education in recent years.Footnote13 The study can thus provide a basis for comparisons of the internationalization of historical research in different countries and regions, and the conditions and imperatives for internationalization in different disciplines.

Measuring internationalization

Internationalization is a notoriously broad, ambiguous concept and there are numerous ways of defining and measuring it. A common quantifiable dimension for STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and some social science disciplines (for example, economics) is the proportion of internationally co-authored publications. Another common measure is the number of international citations of peer-reviewed articles, often limited to periodical publications indexed in the Web of Science citation database. Internationalization can also be measured by the proportion of such articles among the 10% with most citations globally. Yet another measure is participation of researchers in large multinational research programmes, or their use of internationally funded infrastructures.Footnote14

None of these, however, are adequate measures of the degree of internationalization in history, or indeed of most other disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. For example, the proportion of internationally co-authored publications is probably not a significant measure of internationalization in the discipline of history, since only a small proportion of publications in the field are co-authored in the first place.Footnote15 Historical research and infrastructure are generally less costly than in many STEM disciplines, so there is less need for internationalization to pool resources to pay for large research programmes or infrastructure. Most bibliometric measures, moreover, fail to take into account the most important publication channel in history and many other disciplines in the humanities and social sciences: the monograph.Footnote16 These and other problems with using quantitative models derived from the STEM disciplines are well-known, but they are often ignored, downplayed, or inadequately considered in studies of the internationalization of research and in discussions of research policy in general.Footnote17

The problem is aggravated when internationalization, as measured by STEM-derived models, is taken as an indicator of quality or productivity, and used to draw comparisons across disciplines and research fields which in reality have very different channels and models for publication. Hence the deficiencies of the analysis published in the Swedish news magazine Focus in October 2019 as a list of the 800 (nominally) most productive Swedish researchers. The list was divided into eight areas of research – one of which was the humanities – with 100 researchers in each. The rankings were based exclusively on the number of articles listed and cited in Web of Science, and took no account of monographs (even when cited in journals indexed in the Web of Science), neither in terms of absolute numbers nor in terms of citations. One of Sweden’s leading experts in bibliometrics and the analyst behind the ranking, Ulf Sandström, said it bluntly, ‘To publish articles is what research is about’. As might be expected, given the premises and the way the algorithm was constructed, historians fared badly in the rankings. Only one of the 800 top researchers listed was a historian: Hans Hägerdal, a professor of history at Linnaeus University, who ranked as number 77 in the humanities.Footnote18

For present purposes, a more balanced way of measuring and assessing internationalization has been chosen. The article thus uses a mixed methods approach, and includes both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. Quantitative data have been used as much as possible, but it has not been possible to quantify all relevant aspects, such as the number of international citations of publications written by Swedish historians, or their level of participation in international review boards, academic advisory boards, governing bodies, and the like. Other dimensions that do not easily lend themselves to quantitative analysis are the degrees to which Swedish historians participate in international conferences, workshops, and research networks; however, it is likely they show a relatively high degree of internationalization in the those respects, and have done so for a long time.Footnote19

The quantitative part of the analysis instead centres on four dimensions that do lend themselves to quantification: (i) geographical areas of research, (ii) international publications, (iii) international researcher mobility, and (iv) international research funding. Each dimension has been analysed in terms of one to three measurable indicators ().

Table 1. Dimensions, indicators, and measures of internationalization.

The chosen indicators have the advantage of being relatively well defined, measurable, relevant, and comparable over time. The results of the quantitative analyses are discussed qualitatively to provide insights into the reasons for the observed trends. Taken together, this analysis can indicate how Swedish historical research has developed regarding different aspects of internationalization since around 2000.

On balance, to my mind the move towards more internationalization has been a positive one, contributing to what I suggest is the end of methodological nationalism. At the same time, the tendency towards internationalization in recent years has also given rise to worries, some of which appear well founded, about some of its negative aspects, such as a crowding out of Swedish as the main language of academic and popular communication. Such aspects are also discussed in the article.

Here, because of the close historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between the Nordic countries, Scandinavian languages, and geographical areas, studies of the Nordic region or other Nordic counties have not been defined as international. This is in line with previous studies of the internationalization of the discipline of history in Sweden.Footnote20

Doctoral theses as a measure of internationalization in the twentieth century

Earlier attempts to analyse the degree of internationalization and other aspects of the development of the discipline of history in Sweden based on quantitative data have relied mainly on longitudinal studies of metadata about doctoral theses. Despite the limitations of the method, theses have the advantage of providing a coherent, clearly defined, and sufficiently large sample for statistical analysis. Previous studies have thus used statistics pertaining to Swedish theses in history to demonstrate a wide range of historiographical trends, including shifts in thematic orientation, chronological periods of investigation, gender ratios among historians, and the use of unpublished sources.Footnote21

Two aspects are of particular interest: the geographical areas of study and the language. Conny Blom has demonstrated that the interest in international relations culminated in the first two decades of the twentieth century, when close to 40% of all Swedish theses in history had international topics, which for the most part meant Sweden’s relations with foreign, mainly European, powers.Footnote22 After the First World War, interest in the history of international relations declined sharply, and by the 1940s only about 15% of Swedish doctoral theses in history had international topics. This was a remarkable turn of events, because in most of the rest of Europe and the US, the interwar years saw a growing interest in the history of modern international relations against the backdrop of the war and the hunt for its causes. The interwar years also saw a renewed interest in grand syntheses of regional and global reach, often with both academic and popular ambitions, and an increased interest in international comparative history.Footnote23

Historiographers have generally explained this retreat from international history in Sweden with the rise of the ‘history-critical’ school under the auspices of the brothers Curt and Lauritz Weibull. The school was critical of the earlier focus in Swedish historical research on allegedly nationalist historical narratives, including endless studies of Sweden’s international relations. Instead, the Weibull brothers and their followers focused on domestic power struggles in Sweden and Scandinavia, particularly in mediaeval times, when the political fortunes of the Nordic countries were intimately intertwined. The turn away from international history was reinforced by the simultaneous distancing of Swedish historians (and Swedish intellectuals in general) from German influence.Footnote24 The result was that Swedish historians by the mid twentieth century were intent on Swedish and Scandinavian history like never before, and that the surge in interest in the history of modern international relations and imperial history in other parts of the world in the decades following the Second World War gained little traction in Sweden.Footnote25

The 1960s and 1970s saw a renewed interest in international history in Sweden when several prominent historians, including Magnus Mörner, Åke Holmberg, Sven Tägil, and Göran Rystad, established lively research environments and taught large numbers of PhD students, many of whom were internationally recruited. Encouraged by the great contemporary interest in decolonization, much of this research concerned non-European parts of the world, particularly Africa and the Americas. In all, over 30% of the theses in history defended in the 1970s were international investigations in some form.Footnote26 In 1986, Magnus Mörner, in an assessment of internationally oriented historical research in Sweden, argued that the changes had been significant over the previous decades and concluded that ‘the proportion of the historical research in Sweden that nowadays is oriented towards international subjects cannot be regarded as particularly low compared with other smaller countries in Europe’.Footnote27

Mörner’s claim, however, was soon overtaken by events. Shortly after his article was published, the proportion of internationally oriented theses in history dropped sharply and continued to decline during the following decade. By the early 2000s, the proportion of international theses was down to around 17%, roughly the same as it had been in the mid twentieth century. Moreover, as the influential historians who had built the internationally oriented research environments retired in the 1980s and 1990s, there were few senior historians to continue the work they had initiated. Many of the brightest students of the first generation of internationally oriented historians in Sweden also pursued international careers or took up positions in area studies departments and institutes and so had limited influence on the development of the Swedish history discipline.Footnote28

Against this background, in 1997 an assessment of Swedish historical research observed that

It is perhaps surprising that the foreign-oriented research effort has actually decreased quite sharply, mostly due to lessening interest in Swedish foreign policy relations. At a time when the relationship with Europe, globalization processes in the fields of the economy, environmental impact and culture are frequently emphasized, transnational studies are in fact thematized to a relatively lesser extent than before by historians. To some extent it can be seen as a consequence of the choice of subject areas, but the question must still be asked whether this is an expression of a lack of contact with the surrounding society – or a reaction where a problematized Swedish identity results in a stronger orientation towards Sweden.Footnote29

A similar but somewhat less clear-cut picture emerges from an analysis of the other of the two relevant criteria in this context: the proportion of theses written in English or another foreign language widely read among historians such as French, German, or Spanish. In the later 1970s – when the proportion of theses focusing on international conditions peaked – the proportion of theses written in non-Scandinavian languages was 22%, but by the early 2000s that had fallen to 13%.Footnote30

Geographical areas of study

An analysis of the 314 theses in history defended in Sweden between 2001 and 2020 indicates the interest in international history has increased significantly. In 2006–2010 there was a small, statistically insignificant increase in the number of theses with international areas of investigation compared with the previous five-year period (2001–2005), but in the following period, 2011–2015, the proportion almost doubled to 31% compared with the 2001–2005 period, only to fall back somewhat to 27% in the most recent five-year period (2016–2020).Footnote31 The increase is not as strong in absolute numbers, however, which indicates that the increase in the proportion of internationally oriented theses was mainly due to a decline in the number of theses dealing with Swedish or Nordic history (and thus to a decline in the total number of theses), particularly after 2006.Footnote32 Most of the internationally oriented theses either dealt with European history or were studies of international topics involving Sweden (for example Sweden’s economic or political relations with other countries, migration to and from Sweden, Swedish perceptions of international developments or international comparisons and transnational studies including Sweden). The proportion of theses dealing with non-European or global history also increased, from 4% in the early 2000s to 7% in the later 2010s.

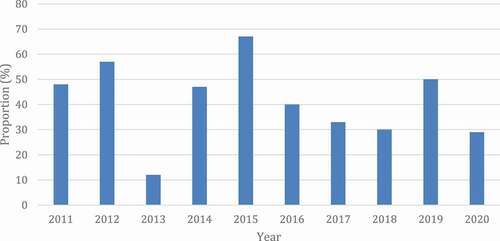

The analysis of the orientation of the doctoral theses has been supplemented by data about the history project applications submitted to the Swedish Research Council between 2011 and 2020.Footnote33 Of 179 projects granted funding in the ten-year period, 74 (41%) had some kind of international orientation, as signalled by the title of the project. Of these, 25 had European areas of investigation, another 25 had a non-European or global orientation, and 24 dealt with international topics involving Sweden and other parts of the world. The small numbers and considerable variations between each year make it impossible to demonstrate any clear trend towards internationally oriented research projects (). The overall result, however, corroborates the analysis by the Scientific Council for Humanities and Social Sciences at the Swedish Research Council in 2019, which came up with similar figures based on a text-mining analysis of project summaries.Footnote34 The approved research projects were also to a greater extent internationally oriented than the doctoral theses in the period 2011–2020.

Figure 1. Proportion of research projects in history financed by the Swedish Research Council, 2011–2020, with international areas of investigation signalled in the title. Source: see n. 33.

The third indicator for the geographical areas of study used here is the research orientation of full professors of history employed at a Swedish university or university college. Information was gathered about the research orientation of the 57 members of staff who were listed as full professors of history by thirteen Swedish universities or university colleges that offer PhD programmes in history, and the main research orientation of each professor was determined by searching the academic publication database SwePub and the national library catalogue LIBRIS. The analysis shows a significant change has taken place in the professors’ interest in international history over the past two decades. Twenty (35%) of the professors have published most of their research on international areas of investigation. European history is well represented and is the main focus of research for eleven of the professors, mainly at Lund University. In contrast to the situation fifteen years ago, moreover, global and non-European perspectives are now also well represented among Swedish professors of history, and are the main focus of interest for eight. Here, Linnaeus University stands out as particularly well represented with four professors (including the present author) whose main area of research is non-European or global history. All four are members of the Linnaeus University Centre for Concurrences in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies, which since its founding in 2012 has become a centre in Scandinavia for the study of colonial and global history. In contrast to the analysis of the theses, the increased interest in international history among the professors is visible both absolute and relative numbers.

The analysis of the theses’ geographical areas of research and the professors’ research orientation both indicate a significant move towards more internationalization in recent years, albeit arguably from low levels in 2000. The trend towards more international history is visible both on the doctoral and professorial levels, but of the two the interest in global and non-European history is more pronounced among the professors – possibly, at least in part, because of differences in international recruitment and mobility, as discussed below.

The analysis of research projects approved by the Swedish Research Council shows no trend towards internationally oriented history, but since over 40% of the history projects approved in the past ten years have an international orientation, international history, as measured by this indicator, stands strong in Sweden. In contrast to the other two indicators, the relative proportion of each of the three categories of international history used here was roughly equal for the research projects. International studies involving Sweden, meanwhile, were more prominent as measured by doctoral theses (where it made up the largest of the three sub-categories) and less pronounced among the professors.

The trend towards more international areas of study is not surprising given the impact global history has had internationally since the end of the twentieth century and the growing importance of global contacts and challenges. Global history was a relative latecomer to Sweden, however, as it started to gain ground only from around 2010, twenty years after the field was first established in the US and subsequently in several other European countries.Footnote35

International publications

The proportion of theses written in English or another of the most read languages worldwide – here French, German, or Spanish – was around 13% in 2001–2005. At 15%, the proportion was only slightly higher in the following five-year period. In 2011–2015, however, the proportion of theses written in English or (sometimes) German more than doubled to 31%, with an abrupt change in 2010–2011. The numbers were almost identical in the last period studied. As expected, English was by far the most dominant of the foreign languages, and only three theses in 2011–2020 were written in another non-Scandinavian language, all in German.Footnote36

Unsurprisingly, and in line with earlier studies, theses with international areas of study are overrepresented among the theses written in English or German. Of the 61 theses written in these languages in the period 2011–2020, 39 had international areas of investigation: 17 concerned European history, 9 global or non-European regions, and 13 international developments involving Sweden. Moreover, of the 57 theses in international history in 2011–2020, 72% (41 out of 57) were written in an international language, which is slightly more than in earlier periods. Theses that had no connection to Sweden regarding the area of investigation were overwhelmingly written in English (88%) or, in the case of three theses in European history, German. For those that dealt with international topics involving Sweden, the proportion of English-language theses was much smaller – 52% (13 out of 25) – with the rest being written in Swedish.

By comparison, of the theses dealing exclusively with Sweden (so not including those dealing with international topics involving Sweden), the proportion written in English was 13% (18 out of 142) in 2011–2020 (and there were none in French, German or Spanish). This is significantly higher than in 1976–2005, when only 3.6% of theses about Sweden were written in English. This is a new development in a longer historiographical perspective too: until the 1990s, only a handful of theses about Swedish history were written in a non-Scandinavian language.Footnote37 Although Swedish is still undoubtedly the preferred academic language for theses on Swedish history, PhD students working on Swedish history today are more open than in the past to the idea of catering not only to a Swedish academic audience but also to an international.

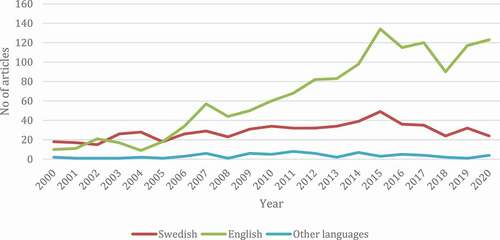

A similar picture emerges from an analysis of peer-reviewed articles in history registered by scholars employed at a Swedish higher education establishment in the database SwePub. There was a decline in the proportion of articles published in English or another internationally read language in the early 2000s (). The lowest proportion was in 2004, when only 11 articles, or 28% of all articles in SwePub, were written in a language other than Swedish. In subsequent years, however, both the number of articles and the proportion of articles written in a foreign language increased sharply. The upward trend continued throughout the 2010s, with the proportion of international publications reaching an unprecedented 82% in 2020.Footnote38 As expected, English is the dominant foreign languages, accounting for 95% of the international publications in the period.

Figure 2. Number of peer-reviewed journal articles about history in Sweden by language, 2000–2020. Source: See n.38.

The largest increase in internationally published articles since the early 2000s is due to the larger absolute number of articles. At least until 2015, the number of articles written in Swedish also held up well, and increased steadily in absolute numbers so that by 2015 the number of peer-reviewed articles in Swedish was roughly twice the number in 2005. The absolute figures, however, should be handled with care because the trend may in part be due to the expansion of SwePub’s coverage.

Worryingly for the use of Swedish as an academic language, there has been a significant decline in the number of peer-reviewed articles in Swedish in recent years, as shown in . In 2015 there were 49 articles in history published in Swedish, but in 2020 the number was 24, or less than half. These figures should also be interpreted with care because of the delay in registrations in SwePub, but given that the trend is observable over several years it is not unreasonable to suspect that to some extent it is due to a crowding-out effect from English publications.

Worries about the marginalization of Swedish as an academic language because of the growing emphasis on international publications are frequently voiced by Swedish historians and other researchers in the humanities and social sciences. Among the principal concerns are a deterioration in the quality of academic discussion, because most Swedish historians are less proficient in English than in Swedish, compounded by the difficulties of translating Swedish terms – particularly historically specific terms – into English. Another concern is a dislocation between research and the public sphere, further marginalizing Swedish historians in the national public sphere.Footnote39

Such worries are worth taking seriously, but against the fears that Swedish historians would be deprived of Swedish as an academic language there are some encouraging signs. In 2013–2014, a controversial suggestion that the Swedish Research Council stop supporting journals in the humanities and social sciences led to loud protests by researchers, the deans of the humanities faculties, and private research foundations. The protests generated an increased awareness of the important function of Swedish-based (and largely Swedish-language) scholarly journals as channels for dissemination and debate and as guarantors of the quality of research.Footnote40 The suggestion was promptly withdrawn because of the protests, and the Swedish Research Council’s current financial framework for humanities and social sciences journals is larger than ever before. Moreover, as a testimony to the high quality of Swedish academic publishing in history, both of the country’s major historical journals, Historisk Tidskrift and Scandia, are listed in the Web of Science: Arts & Humanities Citation Index, despite most of their content being in Swedish.

International researcher mobility

It is difficult to procure detailed data about international mobility for PhD students and staff broken down by individual disciplines. However, there are statistics for broader research areas, such as the humanities, which can be used as proxies. In 2019, the Swedish Higher Education Authority reported that the proportion of foreign doctoral students – defined as students who had entered Sweden to do a postgraduate degree and who had been granted a residence permit for that reason or had immigrated less than two years before they started their PhD – had increased from 20 to 35% of all PhD students in the preceding ten years. The differences were great between fields of research, however, with the proportion of PhD students in the arts and humanities being the lowest of all at 7%.Footnote41 As regards history, it is likely that a relatively large proportion of the PhD students with a non-Swedish background came from other Nordic countries. There are very few non-Scandinavian doctoral students in history in Sweden.

A major barrier to international mobility among PhD students in history – and, presumably, in other disciplines in the humanities – is language proficiency. However, of the thirteen Swedish universities or university colleges with a PhD programme in history, only four explicitly have proficiency (reading or passive proficiency) in Swedish as an admission criterion for PhD students: Luleå University of Technology, Lund University, Mid Sweden University, and Södertörn University. Södertörn, however, makes an exception for PhD students enrolled in its Baltic and East European Graduate School, while the University of Gothenburg requires doctoral students to ‘have such language skills necessary for course requirements and active participation in seminars’, which in practice means a good command of Swedish or another Scandinavian language.Footnote42

In theory, this leaves eight Swedish universities (nine if Södertörn is included) where students can be enrolled in doctoral programmes in history without a working knowledge of Swedish. However, most universities have little or no information about their PhD programmes in history in English on their websites. Both of the two major Swedish research schools in history – the National Research School in Historical Studies (Lund, Gothenburg, Linnaeus, Malmö and Södertörn universities) and the Research School in History (Stockholm and Uppsala) – operate in Swedish, including the majority of courses, workshops, and seminars. PhD positions are often only advertised in Swedish, and when advertised in English proficiency in Swedish may be required for the position, even if this is not a formal requirement under the general study plan. The latter documents, moreover, are often only available online in Swedish.Footnote43

Postdoctoral researchers are normally not required to take courses or to teach to any great extent, and the impression is that they are more likely than PhD students to be recruited internationally. Again, exact numbers are difficult to come by, but there are indications. Heiko Droste, in a recent study of mobility among Swedish historians, found that out of over 300 employed at a Swedish university or university college, 27 had completed their PhD abroad.Footnote44 Since there are only about a handful of lecturers and professors with foreign PhDs, the majority – probably close to 20 – of the 27 were presumably postdoctoral researchers or externally funded researchers.

Another measure of international mobility is the number of Swedish historians doing postdoctoral research abroad. In 2012, the Swedish Research Council launched an international postdoctoral grant programme, which since has been advertised twice a year. In total, 19 early career historians – that is, within two years of receiving a PhD – have been awarded a grant between 2012 and 2020. The figure represents about 9% of the 213 historians who received their PhD between 2010 and 2020. The data from the Swedish Research Council is incomplete regarding the host countries, but out of the eleven grants for which host country data are given, ten involved mobility to another Western European country and one to the US.Footnote45

Other opportunities for international researcher mobility are the EU-funded Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) and Riksbankens Jubileumsfond’s sabbatical grant. Sweden pales in comparison to Denmark and Norway for the MSCA: Sweden was the host country for only 10 out of 458 MSCA Individual Fellowships in history in 2014–2019, compared to 40 for Denmark, 10 for Norway, 5 for Finland, and 1 for Iceland. None of those 10 grants seems to have involved a history department, having been hosted by other related departments such as archaeology, the history of law, and literature studies.Footnote46

A few historians have been awarded Riksbankens Jubileumsfond sabbatical grants, which make it possible for lecturers or professors to spend at least one month abroad (of between six and twelve). In 2014–2020, seven historians were awarded the grant, or roughly 3% of the two hundred or so lecturers and professors of history employed at Swedish higher education institutions.Footnote47

Finally, regarding members of history faculties, a difference can be observed between lecturers and professors. An analysis of the staff pages of the four largest history departments – Gothenburg, Lund, Stockholm, and Uppsala – shows that only one out of thirty lecturers held a foreign PhD, but that four out of twenty-nine professors did.Footnote48 Whereas the proportion of foreign PhDs among of all staff thus corresponds with Droste’s conclusion that 8.6% of all employed historians had received their PhD abroad, there was a significant difference between the 3.3% of lecturers who did so and the 14% of professors.

The impression is thus that mobility among historians in Sweden has increased in recent years, because of measures designed to encourage researcher mobility, particularly in the shape of mobility grant programmes. It is probably relatively common for Swedish historians to spend some of their career in a foreign research environment. In other respects, however, mobility seems more limited. PhD students and lecturers are overwhelmingly recruited from Sweden, whereas internationally recruited postdocs and professors seem somewhat more common. Inward mobility when measured by the number of MSCA fellowships in history is relatively low, though.

Moreover, such mobility as there is, at all levels, is largely concentrated to European countries, mainly Western European and neighbouring countries. The few non-European historians in Sweden mainly come from the US. These trends indicate that the efforts in recent decades to increase researcher mobility have had effects on Swedish historians’ mobility, but that the effects are unevenly distributed between the various career levels. The figures also indicate that intra-European mobility dominates, presumably reflecting the EU’s efforts to encourage cross-country mobility in academic careers.

International research funding

The fourth and last dimension of internationalization considered here is the interest and success of Swedish historians in applying for international research funding, as measured by the opportunities provided by the European Research Council (ERC). In recent years it has been a priority in the humanities and social sciences in Sweden to increase the number of projects funded by the ERC. The grants are prestigious and relatively well funded, typically in the € 1.5–2.5 million range over five years (depending on the funding scheme), so recipients can gather a team of researchers and doctoral students. The research groups are often recruited internationally, though it is not a formal requirement. It is open to all disciplines and fields of research to apply, and applications are evaluated solely on scientific excellence.

In 2019 the Swedish Research Council commissioned a report on the applications and successes of Swedish researchers in the humanities and social sciences in the ERC’s calls for funding. The report concluded that fewer applications from researchers in the humanities and social sciences in Sweden were submitted to the ERC compared with other fields of research, but that their success rate was ‘not particularly low’. The report also found that Swedish researchers fared better than the average of researchers in all eligible countries, whether in the humanities and social sciences or in other research areas.Footnote49 It inferred that the reason relatively few ERC projects went to Swedish scholars in the humanities and social sciences was not that the quality was poor, but that too few applications were submitted.

This conclusion is borne out by the statistics for submitted and granted applications for the three major types of ERC grants in historical studies in 2010–2017. Swedish researchers submitted 35 applications of which 6 were successful in the research domain ‘Social and Humanities 6: The Study of the Human Past’: 17 for a Starting Grant (2 awarded), 10 for a Consolidator Grant (1 awarded), and 8 for an Advanced Grant (3 awarded). The 17% success rate was relatively high – it can be compared to the 10% success rate for the corresponding research area at the Swedish Research Council, History and Archaeology (review panel HS-I) in the same period. However, a far larger number of applications in history and archaeology was submitted to the Swedish Research Council: 978, or almost thirty times as many as those submitted by Swedish historians and archaeologists to the ERC. The small number of submissions to the ERC obviously contributed to the remarkably low proportion of grants awarded to Swedish researchers in the SH6 research domain, which, at less than 1.8% (6 out of 341 granted projects to all countries in the period) was around half that of all research fields combined or 3.4% (377 granted projects out of 10,998). The statistics also show considerable variations between the types of grants. For the whole period for which data is available, 2008–2020, the success rate for Swedish applications for an Advanced Grant in SH6 was an impressive 33% (3 projects out of 9 evaluated), whereas it was 11% (3 out of 28) for a Starting Grant, and only 5% (1 out of 20) for a Consolidator Grant.Footnote50

The variations in the number of submitted applications to each of the three funding schemes indicate that the problem of too few researchers in history and archaeology submitting applications to the ERC – as singled out by the Swedish Research Council report – was most obvious for Advanced Grants. This points to a generation gap, as senior Swedish researchers – defined by the ERC as those who received their PhDs twelve years or more before the application deadline – are less keen than their younger colleagues to put in the substantial effort necessary to write a competitive application for an ERC grant. Similarly, the eight applications for Advanced Grants in 2008–2020 were spread out across the thirteen years, ranging from no applications to two in a year, with no discernible trend in the interest in applying for ERC grants among senior Swedish historians and archaeologists. Much the same is true of the other two funding schemes, although the number of submissions are higher. It remains to be seen if the 2019 report of the Swedish Research Council will encourage Swedish scholars in the humanities and social sciences to submit more applications, which would likely result in more grants.

Thus far the discussion has focused on the SH6 research domain – the study of the human past – which is broader than the discipline of history. On closer inspection, three of the seven successful projects were in archaeology and one in the interdisciplinary field of immaterial rights, while the three projects that could be categorized as history were awarded to researchers at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology’s Division of History of Science. No historian employed at or associated with a general history department has ever had an application for an ERC grant approved by Panel SH6, although at least one Swedish historian, Lotta Vikström, has landed a grant in another panel.Footnote51

here are obviously many other international funding opportunities besides the ERC grants. Swedish historians have been involved in large projects funded under Horizon 2020 and past EU framework programmes for research. However, in view of the small number of history projects funded under the MSCA-IF scheme, the Swedish historians’ applications to the ERC indicate that internationalization as measured by international research funding is relatively low. A possible explanation for the Swedish historians’ low participation rate when it comes to European research funding is that Sweden, unlike many other European countries, may be relatively well equipped with public and private research funding for the humanities and social sciences. The validity of this hypothesis remains to be investigated, however.

Conclusions

Since 2006, the Swedish discipline of history has in certain respects undergone a spectacular internationalization process. Swedish historians’ interest in international history – be it European, non-European, global, or international studies involving Sweden – has increased significantly. The proportion of doctoral theses addressing international topics has doubled since the beginning of the twenty-first century, currently standing at some 30%. Another indication of the internationalization of Swedish historical research is that around 40% of new research projects in history granted by the Swedish Research Council in 2011–2020 concerned international themes, wholly or in part. The trend is also visible in the work of history professors in Sweden today, around a third of whom have devoted most of their research to international, transnational, or global history, which is a higher proportion than in the early 2000s. In contrast to ten or twenty years ago, many professors now also have a strong focus on global and non-European history. Moreover, Swedish historians publish their research in English or (more rarely) other international academic languages to a far greater extent than before, which allows them to participate actively in pioneering international research. In doing so, Swedish historians both participate in the discussions pertaining to global and international history and bring Swedish and Scandinavian empirical results to bear on theoretical and comparative historical research.

This suggests a swift erosion of the national, or possibly Nordic, paradigm that has been a long-standing feature of the discipline of history in Sweden (as elsewhere) since its inception in the second half of the nineteenth century. It also points to a breakthrough for global and transnational history in Sweden since around 2010. These developments, however, have also been a source of some controversy among Swedish historians. Some Swedish historians – Swedish in their geographical research interests and preferred language of publication, that is – have serious reservations about the possible negative effects of an internationalization they seem to believe, at least in some respects, has gone too far. Much of it centres on whether Swedish or English should be the language of academic conversation, teaching, and publication. The decline in the number of scholarly articles in history written in Swedish since 2015 indicates such concerns are not unfounded. The controversy thus looks likely to continue.

Of the other two dimensions of internationalization addressed here – international researcher mobility and international research funding – the Swedish discipline of history seems less internationalized. The opportunities for international mobility, especially in Europe, are probably greater today than ever before for historians at all stages of their careers, and yet Swedish historians do not appear to be among the most mobile researchers, whether compared to other disciplines or neighbouring countries. There are still numerous formal and informal obstacles to mobility, particularly regarding the recruitment of PhD students and lecturers, who must normally have a good command of Swedish in order to be considered as serious candidates for a position. The proportion of internationally recruited postdoctoral researchers seems somewhat higher, but there are very few historians among the incoming MSCA-IF fellows. At 14% of the professors, however, the proportion of internationally recruited senior researchers is somewhat higher than for other groups of staff. It is also notable (if not surprising) that all forms of mobility, regardless of career level, are heavily dominated by intra-European mobility, and there appears to be little exchange with the rest of the world except for the US. This bias indicate that the potential of international mobility to encourage cultural and geographic diversity in the history discipline in Sweden is not used to any large degree.

Finally, another dimension of the internationalization of research where Swedish historians are not particularly active is applications for international research funding as measured by project applications to the ERC. The relatively high success rate for applications submitted by Swedish historians in recent years indicates this side to internationalization also contains potential for improvement.

The most important conclusion to be drawn about the internationalization of the Swedish discipline of history since 2000 is that Swedish historians have come a long way in overcoming the methodological nationalism that has characterized the discipline since its inception in the nineteenth century. Most Swedish historians today do not blindly assume Sweden is the only starting point or frame of analysis for their investigations. True, the majority still focus on Swedish empirical sources and conditions, but in doing so they show a far greater awareness of the need to operate at the forefront of international historical research. The rapid rise in international publications by Swedish historians since the early 2000s, many of which appear in leading international peer-reviewed journals, is testimony to this.

Another sign of the demise of methodological nationalism is the extent to which Swedish historians now choose to investigate themes of global or human interest rather than national or regional concern. In a world that is increasingly interconnected and in which global processes and challenges are high on the agenda in virtually all spheres of life, these developments show that Swedish historians, unlike twenty-five years ago, can no longer can be accused of being out of step with their own times.

It is beyond the scope of this article to compare Swedish developments with other Nordic or European countries. However, a few observations should be made so this study does not fall into the selfsame trap of methodological nationalism. First, the trend towards internationalization of research is not confined to Sweden or a selected number of countries; it is visible across the world, linked to the rise of globalization in recent decades. In Europe, internationalization of research is encouraged by the EU’s policies and funding initiatives. The extent to which the discipline of history is characterized by methodological nationalism has also been discussed in other countries, and such discussions seem to have contributed not only to an increased awareness of the problem, but even to efforts to address it. A systematic comparative study of the differences and similarities between the Nordic countries, and how far the debate in one country influences another, seems a fruitful research agenda for the future.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Martin Åberg and David Ludvigsson for taking the initiative to the edited volume Historikern i samhället (Gidlunds 2021), which stimulated to the writing of this article. Thanks also to the other contributors to the book and the research cluster for Colonial Connections and Comparisons at Linnaeus University for valuable comments and suggestions. Research for this article was funded by the Linnaeus University Centre for Concurrences in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies. I am also grateful to Charlotte Merton for careful editing and language checking and to the two anonymous reviewers for constructive criticism and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stefan Eklöf Amirell

Stefan Eklöf Amirell is a professor of global history at Linnaeus University. He is also the director of the Linnaeus University Centre for Concurrences in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies and the president of the Swedish Historical Association.

Notes

1. Woldegiyorgis et al., “Internationalization of Research,” 162.

2. Torstendahl, “I svensk tappning”.

3. Woldegiyorgis et al., “Internationalization of Research,” 163–64, with cited references.

4. Stier, Internationalisering av högre utbildning, 60. All translations are my own unless otherwise stated. See also Hasselberg, “Internationalisering, språk och vetenskaplig gemenskap” for a recent expression of reservations about the benefits of internationalization of historical studies in Sweden.

5. This definition is close to that of Neunsinger, “Cross-over!,” 6. It reflects the debates and concerns about the discipline of history, which does not exclude other definitions or variants of methodological nationalism; cf. Winner & Glick Schiller, “Methodological nationalism”, who identify three main types in the social sciences.

6. Winner & Glick Schiller, “Methodological nationalism,” 576; Tvedt, “Om metodologisk nasjonalisme,” 492.

7. Norges forskningsråd, Evaluering av norsk historiefaglig forskning: Bortenfor nasjonen i tid og rom. The five members of the commission were the chair Bo Stråth (Sweden), Dorthe Gert Simonsen (Denmark), Thomas Lindkvist (Sweden), Nils Erik Villstrand (Finland), and Anette Warring (Denmark). See Tvedt, “Om metodologisk nasjonalisme”, for a critical discussion of the report and the application of the concept of methodological nationalism.

8. For example, Berger & Conrad, The Past as History. This characterization of the bulk of historical research in Sweden in the twentieth century does not rule out that some Swedish researchers have made important contributions to international theoretical debates, for example on war and state formation in the early modern era, such as Glete, War and the State; Gustafsson, “The Conglomerate State”, or the economic and social history of Latin America, such as Mörner, “Economic factors”.

9. See Haapala, Jalava & Larsson (eds), Making Nordic Historiography.

10. Engman, “Vad är allmänt”.

11. For observations on the internationalization of higher education in history in Sweden in recent years, see Eklöf Amirell, “Svenska historiker och internationaliseringen”.

12. Engman, “Vad är allmänt,” 487.

13. Woldegiyorgis et al., “Internationalization of research,” 162.

14. For example, Van den Basselaar et al., Indicators of internationalization, 15; Woldegiyorgis et al., “Internationalization of research,” 170.

15. Cf. Woldegiyorgis et al., “Internationalization of research,” 165.

16. In 2014, an international inquiry concluded that 95% of researchers in the arts and humanities thought it important or very important to publish research in the form of monographs; Kungliga biblioteket, Öppen tillgång till böcker, 8.

17. For these and other critical perspectives on the fashion for measuring quality and productivity in research and higher education, see Nordin, “Historisk tidskrift i nutid och framtid”; Hasselberg, Vem vill leva i kunskapssamhället?; Bornemark, Det omätbaras renässans.

18. Blume, “Topplista”. The observation here is limited to researchers in the history discipline. Further compounding the problems of the list was the fact that several of the researchers listed as scholars in the humanities were in fact social scientists, for example researchers in business administration.

19. Cf. Stråth, Internationaliseringen behöver kvalificeras.

20. For example, Mörner, “De svenska historikerna och internationaliseringen,” 436; Eklöf Amirell, “Den internationella historiens uppgång och fall,” 259.

21. For example, Blom, Doktorsavhandlingarna i historia 1890–1975 (based on Pikwer, Bibliografi över licentiat- och doktorsavhandlingar i historia 1890–1975); Aronsson, “Historisk forskning på väg – vart?”; Lindegren, “Längre och längre år från år”; Eklöf Amirell, Svenska doktorsavhandlingar i historia; Wångmar & Lennartsson, “Historians and their sources”.

22. Blom, Doktorsavhandlingarna i historia, 27.

23. Floto, Historie, 130–34. Some of the most prominent examples of these international trends are Spengler, Untergang; Wells, Outline of History; Toynbee, Study of History; Nehru, Glimpses of World History; Bloch, Société féodal; Braudel, La Mediterranée.

24. Lilja, Historia i tiden, 57; see further Torstendahl, “Minimum demands” on the Weibull School and Zander, Fornstora dagar on the debates and uses of Swedish history in the twentieth century. On turning away from Germany in the wake of the Second World War, see Östling, Nazismens sensmoral.

25. Eklöf Amirell, “Den internationella historiens uppgång och fall,” 260–61.

26. Eklöf Amirell, “Den internationella historiens uppgång och fall,” 261–62.

27. Mörner, “De svenska historikerna och internationaliseringen,” 441, original emphasis.

28. For a full analysis of these developments, see Eklöf Amirell, “Den internationella historiens uppgång och fall”.

29. Aronsson, “Historisk forskning på väg”, 34–35.

30. Eklöf Amirell, Svenska doktorsavhandlingar, 33–34.

31. Data on 316 theses in history and a selection of theses from the Department of Thematic Studies at Linköping University defended in 2006–2020 from the database Dokhist, compiled by Stefan Eklöf Amirell and available online from the Swedish Historical Association, www.svenskahistoriskaforeningen.se (9 September 2021). The data and classifications of international history used here are compatible with earlier analyses of the geographical areas of study in Swedish doctoral theses. For longer time series they can thus be combined with Eklöf Amirell, Svenska doktorsavhandlingar, 19–24; Eklöf Amirell, “Den internationella historiens uppgång och fall,” 261–64.

32. There were 30 theses dealing with international topics defended in 2001–2005, 23 in 2006–2010, 30 in 2011–2015, and 26 in 2016–2020.

33. The project database SweCRIS, s.v. Organisationstyp = Universitet, Finansiär = Vetenskapsrådet, Ämneskod = 60,101 – Historia. The search results were manually cleared of project grants that financed conferences, journals, and research schools. The first available year in the database is 2011 and it has consequently not been feasible to include 2000–2010; see https://www.swecris.se/sv_se/ (17 March 2021).

34. Vetenskapsrådet, Bilagor, Forskningsöversikt 2019 humaniora och samhällsvetenskap, 23.

35. Manning, Navigating World History, ch. 5. Of some importance for the growth of global history in Sweden was an introduction to the field in the leading historical journal in Sweden, Historisk tidskrift, in 2008, which was followed by a lively debate about the merits and possible pitfalls of different approaches to global and transnational history. See Eklöf Amirell, “Den världshistoriska vändningen”; Torstendahl, “Idén om global historia”; Eklöf Amirell, “Den världshistoriska vändningen och strävan överkomma det nationella paradigmet”; Torstendahl, “Transnationell eller global?”; Müller & Rydén, “Nationell, transnationell eller global historia?”; Neunsinger, “Cross-over!”; Björk, “Att integrera nivåer”.

36. Sources, see n. 31. Again the analysis and categories are compatible with earlier statistical analyses.

37. Eklöf Amirell, Svenska doktorsavhandlingar, 35.

38. SwePub, s.v. Type of publication = journal article, Type of content = peer-reviewed, Research subject (UKÄ/SCB) = History, Year = 2000–2020, http://swepub.kb.se/ (18 March 2021).

39. For examples of these and other concerns in relation to the use of English as an academic language, see for example Östling, “Internationaliseringens gränser”; Fejes & Nylander, “The Anglophone International(e)”; Salö, The Sociolinguistics of Academic Publishing Language; Eyice & Forss, “Avhandlingar och internationalisering”.

40. For a summary of the debates about the future financing of academic journals, see Salö, The Sociolinguistics of Academic Publishing Language, 80–82.

41. Universitetskanslerämbetet, “Många utländska doktorander lämnar Sverige efter examen,” 3–4.

42. Study plans for doctoral programmes at the universities of Gothenburg, Karlstad, Linköping, Linnaeus, Luleå, Lund, Malmö, Mid Sweden, Örebro, Stockholm, Södertörn, Umeå, and Uppsala, available at the website of each university (18 September 2020).

43. For example, three PhD students in history, Uppsala University: Jobs and vacancies, UFV-PA 2021/1010, published 18 March 2021, https://www.uu.se/en/about-uu/join-us/details/?positionId=388319.

44. Droste, “Sveriges historiker och deras mobilitet,” 540.

45. Information provided to the author by the Swedish Research Council, 22 March 2021.

46. Horizon 2020 webgate data, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/dashboard/sense/app/93297a69-09fd-4ef5-889f-b83c4e21d33e/sheet/erUXRa/state/analysis (22 March 2021). I am grateful to Annett Wolf, European Grants Advisor at Linnaeus University, for providing the figures.

47. Riksbankens Jubileumsfond’s project database, s.v. Stödform = RJ Sabbatical; Ämne = Historia, https://www.rj.se/anslagslistning/ (19 March 2021).

48. Data collected from the staff pages for the discipline of history at Gothenburg, Lund, Stockholm, and Uppsala (19 March 2021).

49. Vetenskapsrådet, “Application activity and success at the European Research Council”.

50. ERC funding database,, https://erc.europa.eu/projects-figures/statistics (18 September 2020); Vetenskapsrådet, “Bilagor, Forskningsöversikt 2019 humaniora samhällsvetenskap”. The period 2010–2017 for the analysis of the ERC data was chosen in order to correspond with the Swedish Research Council’s report.

51. Panel SH2: Institutions, values, environment and space; Consolidator Grant 2018. In addition, historians of Swedish origin working abroad have received grants from the council, such as Bo Stråth at the University of Helsinki.

References

- Aronsson, Peter. “Historisk forskning på väg – vart? En översikt över avhandlingar och forskningsprojekt vid de historiska universitetsinstitutionerna samt en kritisk granskning av den officiella vetenskapliga debattens form och funktion i Sverige 1990–1996.” Rapport från Högskolan i Växjö. Växjö: Växjö universitet, 1997.

- Berger, Stefan, and Christoph Conrad. The past as History: National Identity and Historical Consciousness in Modern Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Björk, Ragnar. “Att integrera nivåer. Nya krav på en internationaliserande historieskrivning.” Historisk Tidskrift 130, no. 3 (2010): 2–18.

- Bloch, Marc. La Société féodale: La Formation des liens de dépendance. Paris: Michel, 1939.

- Blom, Conny. Doktorsavhandlingarna i historia 1890–1975: En kvantitativ studie: Delrapport 8 inom UHÄ-projektet Forskarutbildningens resultat 1890–1975. Lund: Historiska institutionen, Lunds universitet, 1980.

- Blume, Ebba. “Topplista: Här är Sveriges mest citerade forskare.” Focus, October 3, 2019. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.fokus.se/2019/10/topplista-har-ar-sveriges-mest-citerade-forskare/

- Bornemark, Jonna. Det omätbaras renässans: En uppgörelse med pedanternas världsherravälde. Stockholm: Volante, 2018.

- Braudel, Fernand. La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l’epoque de Philippe II. Paris: Colin, 1949.

- Droste, Heiko. “Svenska historiker och deras mobilitet.” Historisk Tidskrift 138, no. 3 (2018): 536–544.

- Eklöf Amirell, Stefan. “Den internationella historiens uppgång och fall: Trender inom svensk internationell historieforskning 1950–2005.” Historisk Tidskrift 126, no. 2 (2006): 257–278.

- Eklöf Amirell, Stefan. Svenska doktorsavhandlingar i historia 1976–2005: En bibliografi. Stockholm: Kungl. biblioteket, 2007.

- Eklöf Amirell, Stefan. “Den världshistoriska vändningen: Möjligheter och problem i relation till svensk historisk forskning.” Historisk Tidskrift 128, no. 4 (2008): 2–24.

- Eklöf Amirell, Stefan. “Den internationella historiens uppgång och fall: Trender inom svensk internationell historieforskning 1950–2005.” Historisk Tidskrift 129, no. 2 (2009): 241–246.

- Eklöf Amirell, Stefan. “Svenska historiker och internationaliseringen.” In Historikern i samhället: Roller och förändringsmönster, eds. David Ludvigsson and Martin Åberg, 42–67. Möklinta: Gidlunds, 2021.

- Engman, Max. “Vad är allmänt i den allmänna historien?” Historisk Tidskrift för Finland 76, no. 4 (1991): 485–493.

- Eyice, Mari, and Charlotta Forss. “Avhandlingar och internationalisering.” Historisk Tidskrift 139, no. 2 (2019): 312–324.

- Fejes, Andreas, and Erik Nylander. “The Anglophone International(e): A Bibliometric Analysis of Three Adult Education Journals, 2005−2012.” Adult Educational Quarterly 64, no. 3 (2014): 222–239. doi:10.1177/0741713614528025.

- Floto, Inga. Historie: nyere og nyeste tid. Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1985.

- Glete, Jan. War and the State in Early Modern Europe: Spain, the Dutch Republic and Sweden as Fiscal-military States. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Gustafsson, Harald. “The Conglomerate State: A Perspective on State Formation in Early Modern Europe.” Scandinavian Journal of History 23, no. 3–4 (1998): 189–213. doi:10.1080/03468759850115954.

- Haapala, Pertti, Marja Jalava, and Simon Larsson, eds. Making Nordic Historiography: Connections, Tensions and Methodology, 1850–1970. New York: Berghahn Books, 2017.

- Hasselberg, Ylva. Vem vill leva i kunskapssamhället? Essäer om universitetet och samtiden. Hedemora/Möklinta: Gidlunds, 2009.

- Hasselberg, Ylva. “Internationalisering, språk och vetenskaplig gemenskap.” Historisk Tidskrift 140, no. 4 (2020): 674–686.

- Kungliga biblioteket, Enheten för nationell bibliotekssamverkan. Öppen tillgång till böcker: En utredning inom ramen för Kungliga bibliotekets nationella samordningsuppdrag för öppen tillgång till vetenskapliga publikationer. Stockholm: Kungliga biblioteket, 2019.

- Lilja, Sven. Historia i tiden. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 1989.

- Lindegren, Jan. “Längre och längre år från år: Doktorsavhandlingarna i historia 1960–2004.” Historisk Tidskrift 124, no. 4 (2004): 631–640.

- Manning, Patrick. Navigating World History: Historians Create a Global Past. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- Meyer, Frank, and Jan Eivind Myhre, eds. Nordic Historiography in the 20th Century. Oslo: Department of History, University of Oslo, 2000.

- Mörner, Magnus. “Economic Factors and Stratification in Colonial Spanish America with Special Regard to Elites.” Hispanic American Historical Review 63, no. 2 (1983): 335–369. doi:10.1215/00182168-63.2.335.

- Mörner, Magnus. “De svenska historikerna och internationaliseringen.” Historisk Tidskrift 105, no. 3 (1985): 430–452.

- Müller, Leos, and Göran Rydén. “Nationell, transnationell eller global historia? Replik till Stefan Eklöf Amirell och Rolf Torstendahl.” Historisk Tidskrift 129, no. 4 (2009): 559–667.

- Nehru, Jawaharlal. Glimpses of World History: Being Further Letters to His Daughter, Written in Prison, and Containing a Rambling Account of History for Young People. Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1962 [1934].

- Neunsinger, Silke. “Cross-over! Om komparationer, transferanalyser, histoire croisée och den metodologiska nationalismens problem.” Historisk Tidskrift 130, no. 1 (2010): 2–23.

- Nordin, Jonas. “Historisk tidskrift i nutid och framtid: Några reflektioner over läsarsynpunkter, bibliometri och Open Access.” Historisk Tidskrift 128, no. 4 (2008): 601–620.

- Norges forskningsråd, Divisjon for vitenskap. Evaluering av norsk historiefaglig forskning: Bortenfor nasjonen i tid og rom: Fortidens makt og fremtidens muligheter i norsk historieforskning. Oslo: Norges forskningsråd, 2008.

- Östling, Johan. Nazismens sensmoral: Svenska erfarenheter i andra världskrigets efterdyning. Lund: Lunds universitet, 2008.

- Östling, Johan. “Internationaliseringens gränser.” Respons 3 (2013): 14–15.

- Pikwer, Birgitta. Bibliografi över licentiat- och doktorsavhandlingar i historia 1890–1975: Delrapport 7 inom UHÄ-projektet Forskarutbildningens resultat 1890–1975. Lund: Historiska institutionen, Lunds universitet, 1980.

- Salö, Linus. The Sociolinguistics of Academic Publishing Language and the Practices of Homo Academicus. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- Spengler, Oswald. Der Untergang des Abendlandes: Umrisse einer Morphologie der Weltgeschichte, 1–3. Wien: Braumüller, 1918–1923.

- Stier, Jonas. Internationalisering av högre utbildning: Vad, hur och varför? Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2018.

- Stråth, Bo. “Internationaliseringen behöver kvalificeras.” Blogg Post, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, 2016. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://rj.se/debattinlagg/2016/internationaliseringen-behover-kvalificeras/

- Torbacke, Jarl. “Hundra år av vetenskaplig gemenskap: 25 nordiska historikermöten.” Nordisk Tidskrift 81 , no. 1 (2005): 52–59.

- Torstendahl, Rolf. “Minimum Demands and Optimum Norms in Swedish Historical Research 1920–1960: The ‘Weibull School’ in Swedish Historiography.” Scandinavian Journal of History 6, no. 1–4 (1981): 117–141. doi:10.1080/03468758108578987.

- Torstendahl, Rolf. “Idén om global historia och den transnationella trenden.” Historisk Tidskrift 129, no. 2 (2009a): 235–240.

- Torstendahl, Rolf. “I svensk tappning: svenska historiker under utländsk påverkan.” In Svenska historiker från medeltid till våra dagar, eds. Ragnar Björk and Alf W. Johansson, 31–44. Stockholm: Norstedts, 2009b.

- Torstendahl, Rolf. “Transnationell eller global? slutreplik till Stefan Eklöf Amirell.” Historisk Tidskrift 129, no. 3 (2009c): 234–235.

- Torstendahl, Rolf. “Scandinavian Historical Writing Schneider, Axel, Woolf, Daniel, and Hesketh, Ian eds. .” In The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 5: Historical Writing since 1945, 311. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Toynbee, Arnold J. A Study of History. Vols. 1–12. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1934–1961.

- Tvedt, Terje. “Om metodologisk nasjonalisme og den kommunikative situasjonen: en kritikk og et alternativ.” Historisk Tidsskrift (Oslo) 91, no. 4 (2012): 490–510. doi:10.18261/1504-2944-2012-04-02.

- Universitetskanslersämbetet. “Många utländska doktorander lämnar Sverige efter examen.” Statistisk analys 2019-02-25/1, 2019. Website of the Swedish Higher Education Authority. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.uka.se/download/18.6f6937d1167c5d28e8711eb5/1551796524725/statistisk-analys-2019-02-25-manga-utlandska-doktorander-lamnar-sverige-efter-examen.pdf

- Van Den Besselaar, Peter, Annamaria Inzeot, Emanuela Reale, Elisabeth de Turckheim, and Valerio Vercesi. “Indicators of Internationalisation for Research Institutions: A New Approach.” Report from the European Science Foundation, Member Organisation Forum on Evaluation. Website of the European Science Foundation, 2012. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://repository.fteval.at/118/1/Indicators%20of%20Internationalisation%20for%20Research%20Institutions.pdf

- Vetenskapsrådet. “Bilagor: Forskningsöversikt 2019 humaniora och samhällsvetenskap.” Website of the Swedish Research Council, 2019. Accessed September 18, 2020. https://www.vr.se/download/18.5511f9a7168876f741c12e/1552390306154/Bilaga_HS_Forskningsoversikt_VR_2019.pdf

- Vetenskapsrådet. “Söktryck och framgång vid Europeiska forskningsrådet: En analys med fokus på humaniora och samhällsvetenskap i Sverige.” Website of the Swedish Research Council, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.vr.se/download/18.6bd0597171d2a04c52dd4/1590423023239/So%CC%88ktryck%20och%20framga%CC%8Ang%20vid%20Europeiska%20forskningsra%CC%8Adet_VR_2020.pdf

- Wångmar, Erik, and Malin Lennartsson. “Historians and Their Sources: The Use of Unpublished Source Material in Swedish Doctoral Theses in History, 1959–2015, and in Student Bachelor’s and Master’s Theses, 2010–2015.” Scandinavian Journal of History 43, no. 3 (2018): 365–386. doi:10.1080/03468755.2018.1459370.

- Wells, H. G. The Outline of History: Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind. New York: Macmillan, 1920.

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2, no. 4 (2002): 301–334. doi:10.1111/1471-0374.00043.

- Woldegiyorgis, Ayenachew A., Douglas Proctor, and Hans de Wit. “Internationalization of Research: Key Considerations and Concerns.” Journal of Studies in International Education 22, no. 2 (2018): 161–176. doi:10.1177/1028315318762804.

- Zander, Ulf. Fornstora dagar, moderna tider: Bruk av och debatter om svensk historia från sekelskifte till sekelskifte. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2001.