ABSTRACT

The article discusses the female beauty ideal of the small foot in the Swedish press during the second half of the nineteenth century, as an object for the male gaze in fiction, as an actual fashion ideal, and as a prescribed beauty practice for women. It consists of three parts, analysing different subgenres within the press. First, I show how a male notion of the beauty and erotic attractiveness of the small foot was constructed in short stories and serial novels published in the daily and weekly press. Next, I show how this ideal was visually represented for its realization in every-day life in figures in fashion journals. Both genres presented an ideal unattainable for most women. Third, I discuss articles in dailies and weeklies giving advice on how to take care of feet, warning against ambitions to make the foot look small. Taken together, representations of female feet in the Swedish press involved a construction of the foot that also constructed women as perpetually failing in relation to the existing beauty ideal, making it part of a discursive misogynist practice, according to which women was supposed to invest in their appearance, and were derided and ridiculed when they did.

In 1855, the Stockholm daily Friskytten published a short story entitled ‘An Adventure on Drottninggatan’ (Swe: ‘Ett äfventyr på Drottninggatan’). Drottninggatan, e.g. ‘Queen’s Street’, was a major shopping street in nineteenth-century Stockholm), and in the short story, the narrator urged young men to sit for a few hours in the city’s busiest shopping areas and watch the ‘adventures’ – young women – passing by in their fashionable hats. He had done this many times himself, but the adventure he was about to tell did not begin with a hat. It did indeed come walking in a pink hat, with eyes like ‘diamonds in the sky on a clear night’ and a silk dress, accompanied by an elderly chaperone. But it was not the hat or the eyes that made him follow the girl to her house, but her feet, in brown Moroccan leather shoes. According to the anonymous author, there was nothing strange about this behaviour: ‘He who does not lose his mind because of certain things, he has no head, a great writer once said. One of those things is a small foot. A small foot can drive the greatest head insane’.Footnote1

The author expressed an opinion on the stunning beauty of feet common in Swedish nineteenth-century press. While fashion, ideals of beauty and how they were discussed in public debate and journalism in the late nineteenth century have been thoroughly studied internationally, one central part – shoes and the meanings of the foot – has been understudied. During the second half of the century, the small foot, which had long been an ideal of beauty, became an essential part of descriptions of female beauty and attractiveness, not only in Sweden.Footnote2 However, the limited research on the ideal has focused on the major countries – Britain, France, USA – and on the period’s fixation on the foot and the shoe as erotic objects and fetishes.Footnote3 The importance of the second half of the nineteenth century for the worship of the foot is evident in the history of literature, which is the discipline that has studied the phenomenon most closely. A number of well-known writers of the time have been singled out as foot fetishists, such as Théophile Gautier, Baudelaire, Algernon Swinburne, Anthony Trollope and George de Maurier.Footnote4 Only a few precursors are mentioned in the research, such as Restif de la Bretonne – ‘the greatest foot fetishist of all times’Footnote5 – and John Keats.Footnote6 It was also during this period that the high heel was reintroduced into fashion, having been absent since the time of the French Revolution, an effective means of making the foot look smaller.Footnote7 The late nineteenth century also saw the first scientific analyses of foot fetishism, by the German sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing in 1886 and the psychologist Alfred Binet in 1887.Footnote8

In this article I discuss how the ideal of the small foot was expressed in the Swedish press in the second half of the nineteenth century, as an objectifying trope in depictions of women’s appearance, as an actual fashion ideal, and as a prescribed yet criticized beauty practice for women. It consists of three parts, each analysing different sub-genres within the press. First, I show how a masculine idea of the beauty of the small foot was constructed in short stories and serial novels published in the daily and weekly press. Next, I demonstrate how this ideal was visually represented for its realization in every-day bourgeois and middle-class life, in figures in fashion journals. Both genres presented an ideal unattainable for most women. Finally, I discuss articles in dailies and weeklies that gave advice on foot care and warned against ambitions to make the foot look small. These articles show that the ideal of the small foot involved a construction of the foot that also constructed women as perpetually failing in relation to existing ideals.

Thus, focus is not on eroticism and fetishism, but on the ideal of the small foot as a misogynistic practice. My view of misogyny is inspired by the philosopher Kate Manne. In her book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, she argues that sexism is an ideology that affirms and reinforces unequal gender roles by presenting them as natural and true, while misogyny is the executive force, in Mannes words: the ‘law enforcement’ of that ideology.Footnote9 Misogyny, therefore, should not be limited to outright hatred or hostility towards women. It is a system of oppression that rewards women who uphold the sexist ideology and punishes those who act in ways that oppose or threaten it. Misogyny, as I see it, is a set of practices that aim to maintain an unequal social order in which women are continually diminished and their agency denied. In late nineteenth-century Sweden, I argue, the small foot was one of many components of this set. It was an act of objectification, judging the woman by the appearance of her body parts. It was part of an oppressive regulatory framework, as there were perceptions that clearly affirmed that one should have a small foot, but also widespread ridicule of women who aspired to have a small foot.

This article is about women’s feet. Illustrations of men from the nineteenth century show that small feet were also a male ideal. The daily and weekly press, however, gives the impression that men hardly had feet at all – and the few fashion journals published in Sweden dealt exclusively with women’s fashion. While feet obviously supported men, they made women.

Foot worship in the fiction of the press

The adventure on Drottninggatan was an example of male foot worship, common in fiction published in the Swedish daily and weekly press in the form of short stories and serials.Footnote10 This literature was often inferior but certainly more read in Sweden than both Gautier and Swinburne. It was a standard feature, popular among readers and thus important for publishers for retaining buyers. This section investigates how women’s feet were portrayed in this fiction, of which almost all was built on male third person narratives. Most of the daily press is now digitized. I searched for variants of the word foot, as well as words such as stocking, ankle, calf, shoe and other words associated with the foot, in order to capture foot worship as a fundamental way of relating to women’s feet. I also looked at several weekly magazines, few of which have been digitized. Although the Swedish newspaper market was relatively small compared to the larger European countries, the study still covers hundreds of different texts in a large and growing number of newspapers and magazines. While the perspective in this fiction was mostly male, many authors were women, and the intended readers were men and women of the broad, heterogeneous, and growing urban middle class.Footnote11

The attractiveness of the foot is evident in an 1859 short story, in which a man called Fremmer flirted with a young woman, Line, as she carried a writing casket.Footnote12 ‘You don’t wear bluestockings, do you’, he asked her – the word ‘bluestockings’ (Swe: blåstrumpa) was a pejorative expression for learned women that had entered the Swedish language from English in the 1840s.Footnote13 However, Line was completely uneducated, she did not get the joke and took the statement literally. ‘Astonished, she held out a small foot of the most delicate dimensions, giving a glimpse of the snow-white stocking over the pretty walking shoe’. The girl was puzzled by the question, but her ‘anxiety increased’ when she looked up at Fremmer, and ‘met with a flash from Fremmer’s eye, which seemed to want to devour the whole little shoe in its delight’. Fremmer was the experienced body connoisseur and Line the innocent, foolish girl whose cheeks ‘burst into two glowing roses’ when she met his gaze.

There was a voyeuristic element to the scene, common to many stories; a man watching a woman, the reader seeing the scene from the man’s point of view. Another such moment was described in a short travel story from the rural town of Trosa, published in 1884. The story’s protagonist was spying on some girls playing croquet in a garden. A beauty, perhaps eighteen years old, accidentally hit herself ‘on the little foot’ with the mallet and sank to the ground complaining, whereupon an almost paradisiacal moment occurred for our small-town flâneur:

Her friends rush in and take her to the nearest couch, where she is shamelessly stripped of her footwear. And there goes the sock as well. My goodness, such a cute little foot! Apparently, they don’t know what modesty means here, because they don’t bother to hide the interesting in the situation.Footnote14

Other women were not as innocent as Line and the croquet girls, but well aware of the powers of their feet, like the woman in the short story ‘Doppelgangers and ghosts’, (Swe: ‘Dubbelgångare och gengångare’), published in the Gothenburg daily Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfarts-Tidning in 1882. In front of a man, she calculated the power of her foot to the millimetre as she sat down elegantly on a divan, ‘draping her skirt very tastefully and sticking out 0.049 meters of a delightful little foot in bronzed leather’.Footnote15 A tropical beauty, whom a correspondent from the West Indies claimed to have seen in a fictional letter to Aftonbladet in 1876, behaved in a similar way: she was half-lying carelessly on a couch, and ‘under the thin, airy muslin dress one could see the ankle of a delightful little foot, wrapped in a thin silk stocking’.Footnote16

In ‘Hight and depth’ (Swe: ‘Höjd och djup’), a serial published in Jönköpingsbladet in 1853, the beautiful Sophie is described as waking up and getting up. In ‘sweet reverie’, she first rang the bell for the maiden.

Soon a small foot, then a shinbone, then a calf appeared under the blanket, all of them so finely and harmoniously rounded that the artist’ gaze would have rested on them in amazement.Footnote17

Thus, both the accidental and the more calculated display of a small foot could astonish men, even fill them with awe and erotic longing.

The examples expressed a male voyeuristic gaze, but the readership – expected by editors or de facto readers – was probably not predominantly male. It was, if nothing else, a contemporary prejudice that women read fiction more than men, and while men were thought to appreciate news and politics, the intended reader of the fiction was more likely to be a woman than a man.Footnote18 There are also many examples of foot worship in the fiction published in the growing press aimed especially at women. The short story about Line was printed in Journal for the home, dedicated to the Swedish woman (Swe: Tidskrift för hemmet, tillegnad den svenska qvinnan), and another example was ‘A Stockholm Don Juan’ (Swe: ‘En Stockholmsk Don Juan’), which ran as a serial in Stockholm’s Mode-Journal (Eng: Stockholm Fashion Journal, previously entitled Journal for ladies) in 1856. The Don Juan of the story tried to snatch a stunning wife, with beautiful eyes, a mouth red as roses and ‘a small, small foot’, from an ugly janitor at the customs office.Footnote19

The successful weekly Idun, subtitled Practical weekly for women and the home (Swe: Idun: Praktisk veckotidning för kvinnan och hemmet), often printed fiction in which the little feet appeared. Johan Nordling, the newspaper’s editorial secretary and later longtime editor, wrote the serial ‘The battle for hearts: From the history of a woman’s life’ (Swe: ‘Striden om hjärtan. Ur ett kvinnolifs historia’) in 1890. In it, Count Stjärne, on his daily walk in the countryside, comes across a lonely female hiker who had soaked herself in a forest stream. Her beauty left him ‘struck with the most lively admiration’, and he offered to run to fetch a pair of dry shoes, ‘with a glance down at the high-ankled little feet, sticking out from under the wet hem of the dress’.Footnote20

Female readers were fed such descriptions of beautiful feet and how they were viewed by men. It was a very simple ideal: size mattered, or rather, decided everything. The perfect foot was not just small, it was very small. According to an 1857 serial from published in Jönköpingsbladet and reprinted in other provincial dailies, the ideal was ‘a small foot, a real Cinderella’s foot’ – the ideal of the small foot was of course never more evident than in the fairy tale of Cinderella, which enjoyed great popularity throughout the nineteenth century and especially after Rossini’s opera La cenerentola (premiered in 1817). The author of the 1866 short story, ‘Fortune Favors the Brave’ (Swe: ‘Lyckan står den djerfwe bi’) emphasized the beauty of a ‘Cinderella foot’, while the author of ‘A galosh’, published in Skånska Posten 1888, took the worship of the small foot to a more explicitly fetishistic level: there, a man could not tear himself away from his fiancée’s galosh, in her absence he kissed the little piece, ‘shaped after a Cinderella foot’ – when suddenly the woman appeared and allowed him to put on the galosh and kiss it when it was in place.Footnote21

Writing in 1890, the popular columnist Sigurd (pseudonym of Alfred Hedenstierna) described the ideal contemporary woman as having a modern corset, the soul of an angel, a beautiful face and a child’s foot.Footnote22 Looking at today’s shoe sizes, ‘a child’s foot’ was an apt description of the ideal. It was rare for anyone to give a measurement for the little shoe, but a poem published in the provincial newspaper Lindesbergs Allehanda in 1878 did. The poem described the ideal woman: golden hair, teeth like ivory, a cheek like the rose and smooth as velvet, a kissable purple mouth, and a small foot, barely eight inches.Footnote23 A Swedish inch was 2.472 centimetres, which gives 19.78 centimetres, corresponding to today’s Swedish size 32. The limit for adult sizes, size 35, is 21.9 centimetres (8,6 British inches). Thus, the ideal was indeed a very small foot, also when taken into account that women in the late nineteenth-century Sweden were shorter than they are today.

Did the reader get descriptions of these feet when used for the basic human activity of walking? No, it was only rarely, as with our adventurer in Stockholm, that the woman was described as walking. Men walked, women were sitting on chairs or lying on chaise longues or divans, their little feet poking out from under their long dresses. When foot movement was described, it tended to be of an elusive character. It swayed, as if innocently, but certainly well calculated, as in a short story in the Fredrika Bremer Association’s newly started magazine for women Dagny in 1886: ‘Was she perhaps asleep? No, the foot moved in slow rhythm to the notes of the flute’.Footnote24 It was the same in a short story in Nya Dagligt Allehanda in 1896, signed Marie Stahl, in which a slender girl lay in a chair in front of a fireplace, balancing a small velvet slipper on her Cinderella foot. It could also be a more innocent movement, the woman unaware that a man was watching her, as in a translated serial novel by Julian Hawthorne in Göteborgs-Posten in 1879: ‘The tip of a real Cinderella’s foot peeped out from under her dress. The foot rose now and then and slowly touched the floor’.Footnote25

The little foot peeking out: feet in fashion journals

The fiction of the press not only described a common ideal of beauty. It also prescribed it, educating the public on how a woman’s foot should be presented in social life. Moreover, this male gaze on the foot taught the reader something else: that feet were indeed looked at by men, that they had a special power, that this power could be used, that you could appear to be a special kind of woman if you used it, and that it therefore had to be used with great care and calculation. Showing a foot required know-how.

This section examines how feet were depicted in fashion journals with the implicit aim of training middle-class women in fashionable femininity. Swedish fashion journals are much understudied.Footnote26 However, there is a wide range of research on fashion journals as well as fashion journalism in women’s magazines, particularly in France, Britain, and the US, demonstrating their importance to middle- and upper-class women and fashionability in the second half of the nineteenth century. Fashion journals were the essential tool for many women to learn about and access new fashions – before the days of movies and lifestyle magazines, there weren’t that many other ways to see fashionable dress, and that applied not only to those who wore it, but also to an essential part of the producers, the seamstresses.Footnote27 Fashion journals and women’s magazines also played a key role in producing and maintaining femininity, arguing through both text and image about the roles and expected behaviours of non-working class-women in modern society.Footnote28 To some extent, fashion journals functioned as the kind of conservative, apolitical pseudo-feminism analysed by Rachel Mesch, countering ideals of the New Woman, equality and emancipation by focusing on the opportunities offered to women by a modern, fashionable lifestyle within established social and domestic hierarchies.Footnote29

There is nothing to suggest that the situation was any different in Sweden, although fashion journalism was rare before the 1890s, and fashion journals contained very little text, showing an immense number of figures of dresses, in conjunction with enclosed or available patterns. Folded paper patterns introduced in the US in the 1860s revitalized the Swedish market: in 1873, after a long period without any Swedish fashion journals, three were launched. This section is based on an analysis of available journals up to 1900.Footnote30 With one exception, none were Swedish originals; figures and plates were mostly from Berlin and Vienna, sometimes from France.Footnote31 In one of the few articles analysing Swedish fashion journals from the late nineteenth century, Leif Runefelt has shown, in line with international research, how the many figures in Swedish journals represented not only fashion, but a specific female lifestyle and a set of norms and rules for female appearance and behaviour.Footnote32

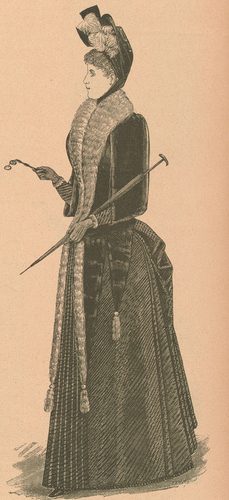

During this period, fashionable dress was depicted in drawings. This made it possible to adapt the female body to ideals to a greater extent than with photography. Fashion journals wanted realistic depictions of clothes, but not of the women who wore them. On the contrary, their figures reminded somewhat of Renaissance Mannerism, with a number of exaggerations such as excessively long, slender bodies and disproportionately long arms and necks. In terms of costume, there were two particularly striking exaggerations, the strong lacing and the small shoes. Women’s waists were narrow and got narrower after the turn of the century when depicted women could have waists as small as their necks. The shoe was depicted as very small and partly hidden under the long dresses.

At least since the renaissance, the ideal proportion for a foot in the world of art has been one-seventh of the body. ‘The foot is the seventh part of the man’, wrote Leonardo da Vinci.Footnote33 The same ideal was sometimes presented in late nineteenth-century press. An article on the appearance and beauty in the short-lived women’s daily newspaper Now (Swe: Nu) in 1894 described the ratio as 1.5:10, which is roughly equivalent to 1:7.Footnote34 But in art, as in so much else in the world, the man was the norm (1:7), and the woman’s ‘little foot’ had to deviate from it in order to be small. So let us see how the foot was depicted in fashion journals.

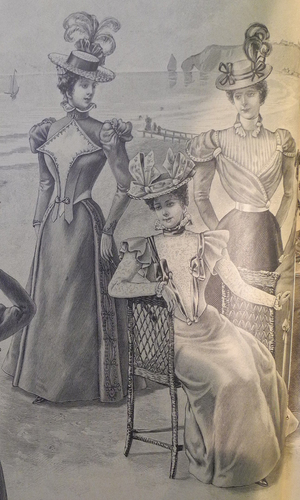

While presenting a normative bourgeois lifestyle, the main purpose of fashion journals was to present fashionable clothes that could be sewn, either at home or by seamstresses.Footnote35 This makes it necessary to point out two things. Firstly, over the years, even in a market as limited as the Swedish one, journals contained thousands of figures of fashionably dressed women, making it impossible here to present anything else but a few samples. Secondly, shoes could be fashionable, but because they were not made at home or by seamstresses, they were never a real topic in the journals. There were no close-ups of shoes or feet wearing shoes, no measurements or textual descriptions of a good or fashionable shoe (which may partly explain why feet are under-represented even in research from Britain and the US). In fact, most figures between 1873 and 1900 show the long dresses that almost touch the ground and completely hide the feet. The women depicted, if they were adults, did not walk like real people, although the most common outfit was clearly the promenade suit. They either stood still or moved slowly and gracefully. The foot was often hidden ().Footnote36

Figure 1. Bazaren, 1873, no. 9; figures 2–3. Reproduction: Anna Guldager, National Library of Sweden.

Many times, however, a foot was visible under the robes, as in Bazaren (Eng: The Bazaar, published between 1873 and 1878Footnote37) in 1874 (). The foot protruded in such a way that the above figure of 0.049 metres makes more sense to us.Footnote38 After a brief period in the mid-1880s when the foot was allowed to protrude a little more, it became less visible and apparently smaller again from the end of the decade. Some figures in the short-lived high-end journal Skandinavisk modetidning (Eng: Scandinavian Fashion Magazine, 1888–89) showed very small feet, more a hint of foot than a foot ().Footnote39 It remained so throughout the 1890s, and this impression was reinforced by the brief mid-decade fad for bell-shaped dresses (). Long dresses were also worn in more informal contexts, such as summer seaside resorts ().Footnote40

Figure 3. Bazaren, 1874, no. 7, figure 1–2. Reproduction: Anna Guldager, National Library of Sweden.

Figure 4. Skandinavisk modetidning, 1889, no. 1, figure 8. Reproduction: Anna Guldager, National Library of Sweden.

Figure 5. Freja. Illustrerad modetidning, 1895, no. 3, figures 71–72. Reproduction: Nordiska Museet.

The examples are representative of figures in fashion journals and show that the small foot was not just a male dream or a fetishism to be explored in the emerging science of psychology, but a very real beauty ideal of the time, worshipped by men, certainly, but cultivated by women. As only a small part of the foot protruded, it is difficult to get an idea of the ideal size by measuring it in relation to the body. However, it is possible – as a pedagogical experiment – to calculate the proportions by looking at figures where the whole foot is shown, as was the case with the sports fashions of the 1890s, especially the cycling fashions. The introduction of the safety bicycle and the special clothing for women that went with it is one of the more studied short-lived trends in fashion history.Footnote41 Cycling made longest dresses impossible, but not only that – in some of the figures of bicycle fashion, the women stood by the bicycle in a different, more determined, less graceful way.

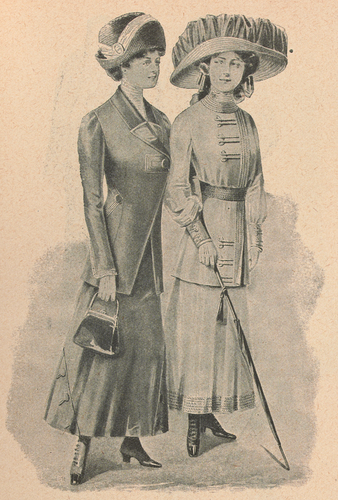

In these figures, the ratio of foot to body is always 1:10 or worse (), meaning that the foot was no more than a tenth of the total length of the body. The number is approximate because all cycling women wore hats. There are also some figures from the 1890s showing women doing other physical activities, such as horse riding and tennis, in which the same 1:10 ratio occurs.Footnote42 Fashion journals thus conveyed the same ideal of the small foot as fiction. As an aside, it should be noted that while the foot generally remained small after the turn of the century, it became both larger and more visible in fashion journals from around 1910. By this time, shorter dresses were allowed in certain contexts, and the foot was simultaneously presented as noticeably larger ().Footnote43

Figure 8. Iduns modell-katalog, 1910, no. 2, figures 325–326. Reproduction: Anna Guldager, National Library of Sweden.

The editors of fashion journals were, of course, aware of both the ideal beauty of the foot and its erotic power. It was only allowed to be shown in its entirety when required by a particular activity, such as cycling or horse-riding. The small foot was part of the ideals propagated by fashion journals, but it could not be exposed more than suggestively in normal social situations, such as strolling in the garden or socializing in the salon. Fashion journals had to contend with criticism from both conservatives and advocates of dress- and lifestyle-reform movements that fashion was wasteful, vain and unhealthy. They could not encourage behaviour that was unacceptable in the bourgeois world. The value of a young bourgeois woman was determined by her value in the marriage market and thus, to a large extent, by her attractiveness in bourgeois life.Footnote44 Being beautiful and attractive meant being pleasant, but not vain or coquettish, so it was important not only to have a small foot, but also to have conscious control over how and when it could be exposed.

This awareness is evident in the fashion journals’ sharp distinction between adult (married or marriageable) women and girls. Motherhood and intergenerational female sociability were central parts of the rhetoric, designed to show that fashion, like any other part of bourgeois life, was a project to be trained into from early childhood.Footnote45 Children and especially girls of every imaginable age were legion in the figures of fashion journals. The foot of the girl – a non-erotic creature – was presented in a completely different way, fully exposed. It is significant that the foot of the adult woman could appear smaller than that of the child ().Footnote46 The boundary between girl and woman, between girls’ and women’s feet was not only to be found in fashion journals, but also in fiction, for example in the short story ‘The Cavalry Captain and the lieutenant’ (Swe: ‘Ryttmästaren och löjtnanten’), published in Jönköpings Tidning in 1866. An officer looked at the young woman Charlotte, ‘about twenty years old’ and wearing ‘a white dress, somewhat short for her age, which allowed him to see a pair of the most beautiful feet’. The reference to her dress being too short shows that Charlotte had not yet understood that she had grown up. She should know not to expose her feet and attract an inappropriate male gaze.Footnote47

Cinderella’s Swedish stepsisters: foot moralism

At the end of the nineteenth century, with a growing niche in the press for magazines and columns aimed wholly or partly at women, and with a slowly emerging consumer culture based on the choice of various industrially produced products, articles on appearance and beauty care became increasingly common. Fashion and beauty had been discussed publicly in Sweden at least since the first wave of moral-philosophical journals in the 1730s, but for more than a century the debate was a moralistic and conservative critique, deriding perceived excesses as indulgent and accusing women who tried to be beautiful of vanity and extravagance.Footnote48 From the late nineteenth century, the discussion became more nuanced and more accepting of the prevailing ideals. It was part of a newer consumer culture in which print commodities (magazine articles, advice books, advertisements) taught women to achieve ideals by using equally commercial methods and commodities.Footnote49 At the same time, there was a hygienic awakening in society, with a greater emphasis on taking care of the body.Footnote50 An older moral critique of fashion as wasteful and sinful was replaced by a medical and hygienic one, particularly represented by the dress reform movement, which promoted healthier and supposedly natural dress that increased women’s mobility. In Sweden, the dress reform movement mainly attacked corsetry, long skirts and other impractical clothing, while it was less interested in shoes.Footnote51 The criticism of the small foot discussed below is somewhat similar to the medical or pseudo-medical opinions on the dangers of lacing, and the dress reform movement’s criticism of what it considered to be unnatural fashions.Footnote52 However, it was expressed independently of the dress reform movement and had a clearer moral slant, which may have had to do with the erotic power of the foot.

Although less judgemental, the discussion of female beauty in the late nineteenth century was often paradoxical, presenting beauty both as an innate female quality and as the result of hard work. This paradox applied to the skin, the hair, the hands, the figure, but was perhaps most evident in the foot, because the ideal was so simple, and so unattainable. How could one work to get a small foot? How could it be achieved through the selection of products and methods offered by the market? There were certainly many opinions and advice on the care or mistreatment of feet. A beautiful foot required constant work. An early advisory article, ‘Beautiful Hands and Feet’ (Swe: ‘Wackra händer och fötter’), printed in Norrköpings Tidningar in 1877, argued that there was a lady’s foot, just as there was a lady’s hand. A beautiful hand was well-groomed and unmarked by work, and so was a beautiful foot: ‘The feet, like the hands, are purely noble beauties, the lower classes cannot take the necessary care of them’.Footnote53 The beautiful foot did not work (walk, stand, carry the weight of the body), but was the object of work.

Women’s feet were delicate and not to be neglected. The signature Dolly Roon, who wrote a series of articles in Idun with advice and tips for the modern woman, said in 1890 in ‘A lecture to the ladies’ (Swe: ‘En föreläsning för damerna’) that black stockings were disastrous for ‘your little feet’ in summer. They attracted mosquitoes, the woman who was bitten would itch both bites and socks, and particles of black dye would penetrate the bites and inflame them.Footnote54 The anonymous author of the article ‘Something about the hygiene of the foot’ (Swe: ‘Något om fotens hygien’) in Vårt Land in 1900 argued that feet needed at least the same care as hands and face, especially since they were ‘locked up in tight leather covers’ all day. This meant washing them every day in warm water with drops of ammonia, taking care of their nails, changing their socks every day and making sure their shoes were comfortable to avoid corns.Footnote55

In a fashion column in Idun in 1890, Helena Nyblom, a well-known writer, described the ideal type that she thought Swedish middle-class women should emulate: the lady of the landed gentry who had mastered the art of dressing properly but simply, without ostentation. She gave the example of two such women she had met on a train:

It was a real satisfaction to see once again a dress that fit so well and was so dazzlingly clean, such fine little feet in matching shoes, such pretty gloves, such well-combed hair, and all without the slightest pretense of being particularly modern or stylish.Footnote56

Here, the small feet became part of an ideal of beauty that could be aspired to and achieved if one was attentive, educated in taste and fashion, knowledgeable about appropriate simplicity and diligent in one’s pursuit.

But it couldn’t be? A woman could get a well-fitting dress and shoes to match, but a small foot was hard to come by if she did not already have one. The beauty columns could only give advice on how to keep the foot healthy, not on how to reduce its size. However, they were able to point out the dangers – medical and ethical – of trying to make the foot appear small. There seemed to be some consensus in the columns that many women were wearing shoes that were too small, with high heels to make their feet look smaller. As beauty advice grew, so did the admonitions not to wear shoes that were too tight or too high: ‘It is known that women, even if they have never-so-small and pretty feet, regardless like to squeeze them into as tight booties as possible’, Göteborgs-Posten claimed in 1883.Footnote57

The writer Mathilda Langlet, who like Nyblom was well known in her time, argued in Idun 1888 that shoes that were too tight could cause death, just as she believed that tight lacing could, by inhibiting blood circulation.Footnote58 Just a few weeks later, Dolly Roon, in the article ‘Tight footwear’, warned against the use of small shoes. Many women had come to regret that they lived by the old Swedish proverb, ‘if you want to be beautiful, you have to suffer pain’ (Swe: ‘Den som vill vara fin får lida pin’), using small shoes to make the feet look ‘pretty, teasing and small’.Footnote59 In the 1880s, self-proclaimed corn-removal surgeon E.C. Åbjörnson travelled the country selling his services while giving lectures on foot care that were reprinted in the press, including an attack on high heels, which he believed women wore to make their feet look smaller.Footnote60

Several articles suggested a connection between the nerves of the foot and the brain. The article ‘Something about the hygiene of the feet’ in Vårt land claimed that the nervous ailments so common among modern women could in many cases be traced back to tight shoes or high heels. Instead ‘Look at your feet’, published in the weekly Förgätmigej (Eng: Forget-me-not) in 1895, emphasized the connection of the nerves between the foot and the eye and that tight shoes and high heels caused problems with the visual organs.Footnote61 It was an idea that had been in vogue for some time; in 1880 an anecdote from an American newspaper was published in many Swedish newspapers about a woman who went to the doctor because of severe sight problems, and the doctor asked to see her foot. ‘Underneath the richly ornamented silk dress, a pretty little foot appeared, encased in an elegant canvas boot with an annoying two-inch heel at about the middle of the sole’. The doctor told the woman – with a ‘cold and contemptuous smile’! – to go without such shoes for a month. Only then could they talk about the eye problems. She took his advice and the problems went away.Footnote62

The warnings about tight shoes can certainly be seen as medical and health-related. Everyone knows that shoes that are too small are painful. But there was an element of nemesis divina, that women with too-tight shoes had only themselves to blame for any misfortune, and that others should learn from their example. In 1883, Öresunds-Posten reported about a twelve-year-old girl in America who died because her shoes were too small: she had chafings but did not stop wearing her ‘bird’s beak-like shoes’, within short dying from blood poisoning.Footnote63 Dagens Nyheter reported in 1886 on 19-year-old Miss Ada Barnakou in London, who danced all night in shoes that were too tight, was tormented but ignored it, and danced the next night at another ball – where she soon fell down unconscious from blood poisoning caused by the dark dye in her stockings seeping into her chafings. ‘To save the unfortunate girl’s life, both feet had to be amputated’.Footnote64 Such warnings were not medical, of course, but moral. These women were coquettes who deserved the contemptuous smiles of doctors. That’s why Dolly Roon added the word teasing in her article on ‘Tight footwear’: ‘pretty, teasing and small’. The thing to be teased was the male gaze, not to be provoked by decent middle-class women.

Does anyone believe”, asked a ‘Doctor G.S.’, who lectured on hygiene and beauty in Svensk Damtidning in 1898, that a woman with shoes that are too tight could be happy, or that ‘the knowledge that the shoes are beautiful can give her satisfaction when her feet hurt?’Footnote65 No one believed that, the doctor claimed, so how come women still wore shoes that were too tight? The answer was that there was a particular type of woman who wore tight shoes: the coquette. In her case, no advice could help other than warnings. ‘The more vain a person is, the more ruthlessly she tends to treat her foot’ said the article ‘Foot care and barefoot walking’ in Jämtlands Allehanda in 1895: ‘Many people want to have a small foot who don’t have it’, using small shoes to their own detriment.Footnote66

According to Jämtlands Allehanda, shoes should be large and roomy, different for left and right (which was not the norm at the time, both shoes were made the same) and have low, wide heels. Such advice created a dilemma for women who wanted to look good in bourgeois society. They were supposed to be beautiful and there were clear ideals of beauty, one of which was to have a small foot, but according to the contemporary press those who tried to achieve these ideals were coquettes. The only way for most women to somehow live up to the beauty ideal of the time, the use of tight shoes and high heels, was denied to the decent woman. When articles about how women should look after their feet and their shoes said that it was coquettes who wore shoes that were too small, and that it was both medically and morally reprehensible to do that, the interesting situation arose that a coquette could be recognized by her small shoes. This meant that women who had small feet and lived up to the ideal risked being looked down upon. The small shoe became the sign of the coquette.

Returning to fiction, we see how the tight shoe was part of the image of the coquette. An example is Victoria Benedictsson’s short story ‘The Coquette’ (Swe: ‘Koketten’), about Countess Stahr who used make-up and high heels in social life, and was unhappy and lonely at home, ignored by her equally vain husband: ‘She looked down at her feet. The Atlas shoes were tight and the ankles were high; they were swollen again’.Footnote67 The short story ‘Miss Amalia’ published in Arbetets Vän (Eng: The Worker’s Friend) in 1887, described the wealthy merchant’s daughter Amalia as sitting idly in a chair on the veranda, a French novel in her lap, her waist laced, her hands in long gloves, her hat heavy with feathers and ribbons, ‘and the unnaturally small, high-heeled, sharp-toed shoes that stick out under the richly draped skirt’. She was unhappy because all this physical confinement tormented her, and she herself expressed the moral of the novella: ‘“I have everything this world can offer me”, she thinks, “youth, wealth, talents, and yet I am not happy”’.Footnote68

But it was not only the tight shoe that could be presented as a characteristic of the coquette, but the small foot itself. In Idun in 1893, Anna Wahlenberg wrote a story about a meeting between the prefect Öhrström and the young Hedvig, both of whom had been trained by balls, dinners and promenades in ‘the very modern sport of “flirtation”’. Hedvig was ‘a voracious little lady’, never satisfied with flattery. Now she was half-lying on a comfortable armchair, ‘with her outstretched little feet crossed, leaning back in a teasing, self-indulgent position’, smiling self-consciously. The prefect admitted that he was prepared to re-educate himself as a wigmaker just to be able to take care of Hedvig’s curly hair every day, but it wasn’t the hair, it was the little feet that Wahlenberg repeatedly pointed out: how small they were when ‘she stretched the crossed little feet even more’.Footnote69

Conclusion: the foot as a misogynistic practice of looking

In the late nineteenth century, the small foot was a well-established ideal of feminine beauty. Both men and women wanted it, but in different ways. Men wanted to look at it and perhaps do more than that, women wanted to have it and if they did not, they tried to fake it – at least according to the advice columns. The ideal was as difficult to achieve as it was firmly established. It’s hard to say whether the critics were right when they claimed that women wore wear shoes that were too small, but of course stories of amputations and deaths were as much a hoax as any alleged deaths from corsets. That middle-class women really did try to hide their oversized feet became clear to dress reformers in the 1890s. They promoted a shorter skirt fashion for hygienic, aesthetic and practical reasons, but admitted that they faced strong opposition from the intended users as such a fashion exposed the feet.Footnote70 A pointed shoe sticking out under a wide dress was in keeping with the ideal of beauty – from which a comfortable, shorter dress distanced most women.

The foot was only a part, but an important one, in the construction of beauty that constituted the ideal bourgeois woman. It was the first or last in a series of reference points for the nineteenth-century male gaze: hair, face, eyes, mouth, neck, bosom, arms, hands, waist, calf, ankle. In this way, the foot was an integral part of the privilege of male visuality in the emerging consumer society of the late nineteenth century. The right to look and the obligation to be looked at were not equally distributed in the world, and the female foot was considered to be an object to be gazed upon.

It was a problem that the small foot, like the lily-white hand, was a sign of class, but at the same time a sign of the coquette. The hand differed from the foot in such a way that it lacked erotic power in most representations in fiction or fashion journals. The foot, on the other hand, was charged with erotic implications. This made showing the foot a specific skill and a balancing act for fashionable women. The 0.049 metres may have been more accurate than it first appears, there was a degree of calculation involved, a certain knowledge of how to display the foot. Put simply, the small foot was to be shown because it was part of the bourgeois ideal and something that separated the wearer and the world of the wearer from the working classes, but it was not allowed to be shown because showing a small foot was the mark of a coquette and an act potentially charged with eroticism. The small foot as a beauty ideal was an example of the ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’-situation that Ellen Bayuk Rosenman identified as the double bind of fashion: women were expected to invest heavily in their appearance, and were then ridiculed and derided for doing so.Footnote71 In this way, the foot was incorporated into a misogynistic discourse that produced ambiguous ideals, which also applied, for example, to the laced waist – it was to be achieved, but it was not entirely acceptable to achieve it. No matter how they behaved, women came up short in the public conversation about beauty. The small foot was an ideal of beauty, but it was also a patriarchal technique of domination and a misogynistic practice of looking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leif Runefelt

Leif Runefelt, PhD in Economic History and a professor in the History of Ideas at Södertörn University, Sweden, is specialized in the Swedish history of consumption and consumer culture during the transition from early modern to modern society, ca 1700–1920. Among fields of studies are press advertisements, 19th-century entertainment, and fashion.

Notes

1. “Ett äfventyr på Drottninggatan,” Friskytten, May 26, 1855. All translations from Swedish are my own. Morocco leather: Swe: ‘saffian’.

2. Perrot, Fashioning the Bourgeoisie, 104–06. See for instance Fischer, “Pantaloons and Power,” 18–21 with references, on early nineteenth-century beauty ideals of the small foot.

3. Perrot, Fashioning the Bourgeoisie, 11, 26, claims that feet acquired a particular erotic power in nineteenth-century bourgeois life because fashion emphasized breasts and buttocks but hid feet under wide dresses; for a critique, see Steele, “Shoes and the Erotic Imagination,” 251, who instead emphasizes the increasing display and commercialization of sexuality. See also Fischer, “Pantaloons and Power,” 186.

4. Ribeyrol, “Poetic Podophilia”; Ribeyrol, “The Feet of Love”; Byler, “If the Shoe Fits”; Jenkins, “Trilby: Fads, Photographers, and Over-Perfect Feet”. See also Carter, “Consuming the Ballerina”.

5. Ribeyrol, “Poetic Podophilia,” 220.

6. Wyngaard, “The Fetish in/as Text”; Marggraf Turley, “Strange longings: Keats and Feet”. As Díaz Cornide, La Belle-Époque des amours fétichistes, 189–91, points out, Restif was forgotten during the early nineteenth century, and his rediscovery in the later part of the century was much due to the period’s interest in podophilia.

7. Semmelhack, “A Delicate Balance: Women, Power and High Heels,” 230; Shawcross, “High Heels,” 408–9.

8. Ribeyrol, “Poetic Podophilia,” 215, 217. Steele, Fetish: Fashion, Sex and Power, 120, Steele claims that foot fetishism was hardly more common in the nineteenth century than it is today, but that the phenomenon seems to have begun then.

9. Manne, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, 78–9.

10. I do not speak of ‘foot fetishism’. Steele, Fetish: Fashion, Sex and Power, 23–4, conceptualizes fetishism on a four-level scale of intensity. The first is that ‘a slight preference exists for certain kinds of sex partners, sexual stimuli or sexual activity’. The word fetish should not be used for this level. The next level is a stronger preference, the third that ‘specific stimuli are necessary for sexual arousal and sexual performance’, and the last that ‘specific stimuli take the place of a sex partner’; this article deals with level 1 and perhaps level 2, and only in a discursive sense, which is why I cannot talk about foot fetishism.

11. On the development and readership of nineteenth-century Swedish press, see Gustafsson and Rydén, Den svenska pressens historia.

12. “En berättelse om huru berättelsen kom till,” Tidskrift för Hemmet, 1859, no. 3, 161

13. “Blåstrumpa,” Svenska Akademiens ordbok.

14. “Reseepistlar från vår “flygande”, 5,” Tidning för Hedemora, Säter och Avesta eller Södra Dalarnes Tidning, September 9, 1884. For voyeurism, see also Axel, “Derute på landet!,” Jönköpingsbladet, January 31, 1857; “Mördaren och polisspionen,” Vikingen, October 13, 1883.

15. “Dubbelgångare och gengångare (novell),” Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfarts-Tidning, August 19, 1882.

16. “Om bord å en kofferdiman (Från Aftonbladets specielle korrespondent),” Aftonbladet, October 20, 1876. See also “Ett svårt val. Roman af Mrs Alexander. Öfversättning för Helsingborgs Dagblad af Ellen Wester,” Helsingborgs Dagblad, January 3, 1895.

17. Axel, “Höjd och Djup,” Jönköpingsbladet, April 19, 1853.

18. Larsson, En annan historia. Om kvinnors läsning, 27–31; Ballaster et al., Women’s Worlds, 76.

19. “En Stockholmsk Don Juan,” Stockholms Mode-Journal, 1856, 84.

20. Johan Nordling, ”Striden om hjärtan. Ur ett kvinnolifs historia,” Idun, 1890, 319. See also Ave (pseud. for Eva Wigström), “Skogsfrun. Berättelse för Idun,” Idun, 1889, 361.

21. “En galosch,” Skånska Posten, August 24, 1888.

22. “Kaleidoskop. En fläck på ett qvinnolif,” Smålands-Posten, July 29, 1890, reprinted in a number of dailies. It was anonymour, but later published under Hedenstierna’s well-known pseudonym, Sigurd, Fröken Jennys konditioner, 146.

23. “Allmän efterlysning (Insändt.),” Lindesbergs Allehanda, March 1, 1878.

24. “Sport,” Dagny, 1886, 169.

25. Marie Stahl, “En första vals,” Nya Dagligt Allehanda, Februari 1, 1896; “Mrs Gainsboroughs diamanter. Berättelse af Julian Hawthorne. Öfvers. från engelskan,” Göteborgs-Posten, July 18, 1879. The novel ran in 1883 in a number of Swedish newspapers and again in 1892. The descriptions here are reminiscent of the French ones in Perrot, Fashioning the Bourgeoisie, 105.

26. Exceptions are Andersson, “Too Anxious to Please,” which analyses the one existing early nineteenth century fashion journal in Sweden; Hilborn, “Den eleganta cyklisten”; Runefelt, “The Corset and the Mirror”; Bäckström, Förmedling av mönsterförlagor; Törnvall, “From Paper Patterns to Patterns-on-Fabric”.

27. Walsh, “The Democratization of Fashion”; Bohleke, “Americanizing French fashion plates,” 121; Törnvall, “From Paper Patterns to Patterns-on-Fabric,” 56–8.

28. Seminal works on women’s magazines and women readers are Beetham, A Magazine on Her Own; and Ballaster et al., Women’s Worlds. See also Moruzi, Constructing Girlhood through the Periodical Press, 1–20; Korte and Lethbridge, “A Wreath of Freedom and Control: The Kränzchen Periodical”; Boardman, “A Material Girl”. For fashion magazines and plates specifically, see Breward, “Femininity and Consumption”; Bland, “Shaping the life of the New Woman”; Bohleke, “Americanizing French fashion plates”; Marcus, “Reflections on Victorian Fashion Plates”.

29. Mesch, Having It All in the Belle Epoque, 1–30.

30. Two more successful fashion journals started in 1873 were based on German originals: Bazaren was a Swedish version of Der Bazar, while Freja was based on Die Modenwelt. A translation of the French Revue de la Mode appeared only in three issues. Swedish fashion journals published from 1873 to 1900 and included in the inventory for the article: Bazaren (1873–1878), Freja (1873–1907), Bilder och text från modeverlden, (appendix to Idun, 1888), Skandinavisk modetidning (1889), Iduns modetidning (1890–1903), Nordisk mönster-tidning (1884–, renamed 1899 Allers Mönster-Tidning), and Modenytt (1900–1901).

31. Modenytt (1900–1901) was the only Swedish original, ambitious but more of a fanzine than the franchised journals.

32. Runefelt, “The Corset and the Mirror”.

33. Da Vinci, “Human Proportions,” 214.

34. “Utseendet. III. De vackraste qvinnorna,” Nu. Damernas dagliga tidning, 1894, no. 4.

35. Törnvall, “From Paper Patterns to Patterns-on-Fabric”.

36. Bazaren, 1873, no. 9; ; Iduns modetidning, February 5, 1897, figure 35.

37. Bazaren, from 1875, Nya Bazaren, was a translated version of every second issue of the German market leader, Der Bazar. Reemortel, “Women Editors and the Rise of the Illustrated Fashion Press,” has shown that Der Bazar had many international versions, but seems unaware of, or makes at least no mention of, the Swedish one.

38. Bazaren, 1874, no. 7, .

39. See for instance Freja, 1885, no. 13, figure 42; Skandinavisk modetidning, 1889, no. 1, .

40. Freja, 1895, no. 3, figures 71–2; Iduns modetidning, June 5, 1897, figures 26–8.

41. See for instance Christie-Robin, Orzada and López-Gydosh, “From Bustles to Bloomers”; Chen, “Its Prohibitive Cost”. For the Scandinavian context, see Hilborn, ‘Den eleganta cyklisten’.

42. Freja, 1897, no. 19, figure 35. See also Freja, 1896, no. 5, figure 62; 1897, no. 7, figures 28–9; Iduns Modetidning, May 20, 1899, ; hiking in Iduns modetidning, June 5, 1898, figures 23–4; riding costume, Iduns modetidning, December 2, 1899, figure 56.

43. Iduns modell-katalog, 1910, no. 2, figures 325–6.

44. Gedin, “Att få lov”; Runefelt, Den magiska spegeln, 125–80; Runefelt, “Modedockan”.

45. Moruzi, Constructing Girlhood through the Periodical Press, 56; Breward, “Femininity and Consumption,” 77–8; Korte and Lethbridge, ”A Wreath of Freedom and Control: The Kränzchen Periodical,” 566.

46. Freja, 1892, no. 4, .

47. “Ryttmästaren och Löjtnanten,” Jönköpings Tidning, March 14, 1866. Reprinted for instance in Eskilstuna-Korrespondenten, July 24, 1866. See also Friedrich Gerstäcker, “Systrarna. Berättelse. Öfversättning af Pehr Lange,” Norrköpings Tidningar, January 21, 1873, 16.

48. Runefelt, Att hasta mot undergången; Helmius, Mode och hushåll.

49. Ballaster et al., Women’s Worlds, 2; Breward, “Femininity and Consumption,” 72.

50. Research on Sweden is limited, however, see Runefelt, Den magiska spegeln, 125–80, as well as several contributions with references in Annola, Drakman and Ulväng, eds, Tvål, vatten och flit. It was of course a European process, see for instance Buxton, “Health by Design,” 460–2.

51. Steorn, “Konstnärligt antimode”; Bagherius, Korsettkriget, 119–77. As Steorn, 228, points out, the Swedish dress reform movement was strongly influenced by the British and American movements (although completely skipping any attempts to introduce pants).

52. Steorn, “Konstnärligt antimode,” 236–7; Summers, Bound to Please, 87–107; Fields, “Fighting the Corsetless Evil,” 355–8.

53. “Wackra händer och fötter,” Norrköpings Tidningar, April 20, 1877.

54. Dolly Roon (pseud.), “Om maj månad och Heinrich Heine, om myggbett, svarta strumpor, sympatikurer och rullkaminer. En föreläsning för damerna,” Idun, 1889, 188.

55. “Något om fotens hygien,” Vårt land, October 20, 1900.

56. Helena Nyblom, “Mode och smak. Några iakttagelser af Helena Nyblom,” Idun, 1890, 148.

57. “Hvarjehanda,” Göteborgs-Posten, July 24, 1883.

58. Mathilda Langlet, “Frihet och tvång,” Idun, 1888, 54.

59. Dolly Roon, “Trånga skodon,” Idun, 1888, 102.

60. “Ditt och datt,” Ystads Tidning, March 3, 1882. Åbjörnson advertised for his foot care services in the same issue.

61. “Något om fotens hygien”; “Se på edra fötter,” Förgätmigej, 1895, 269.

62. Först tryckt i “Blandade ämnen,” Nya Dagligt Allehanda, June 18, 1880, reprinted in a number of dailies.

63. “Från Amerika,” Öresunds-Posten, July 17, 1883.

64. “Trånga skor,” Dagens Nyheter, March 10, 1886; reprinted in provincial dailies such as Ljungby-Posten, Helsingborgs Dagblad, Westerwiks-Posten and Cimbrishamnsbladet.

65. ”Hälsa, kraft och skönhet. En hygienisk föreläsning för damerna, i tre kapitel. Af d:r G.S. III. Skönhet,” Svensk Damtidning, 1898, 145.

66. “Fotens vård och barfotagång,” Jämtlands Allehanda, July 3, 1895. For a discussion of the coquette as a type in nineteenth-century critiques of fashion and femininity, see Bayuk Rosenman, “Fear of Fashion”.

67. Ernst Ahlgren (pseud. for Victoria Benedictsson), “Koketten,” 25.

68. H.E., ”Fröken Amalia”, Arbetarens vän, April 29, 1887.

69. Anna Wahlenberg, “I infattning,” Idun, 1893, 420.

70. See for instance Cric Cric (pseud. for Elsa Lindberg), “Litet om nya moder,” Hemmet. Läsning för ung och gammal, 1897, 125; “Dräktreformens kjolmöte,” Idun, 1897, 22; “I Kjolfrågan,” Idun, 1897, 38; Maria Nyström, “Sociététens martyrer,” Idun, 1894, 375.

71. Bayuk Rosenman, “Fear of Fashion,” 12; see also Breward, “Femininity and Consumption,” 75; Ladd Nelson, “Dress Reform and the Bloomer,” 22.

References

- Ahlgren, Ernst. “Koketten.” In Från Skåne. Studier, 16–26. Stockholm: Alb. Bonniers förlag, 1900.

- Andersson, Gudrun. “Too Anxious to Please: Moralising Gender in Fashion Magazines in the Early Nineteenth Century.” History of Retailing and Consumption 6, no. 3 (2020): 216–244. doi:10.1080/2373518X.2021.1915593.

- Annola, Johanna, Annelie Drakman, and Marie Ulväng, ed. Tvål, vatten och flit. Hälsofrämjande renlighet som ideal och praktik ca 1870–1930. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2021.

- Bäckström, Hanna. Förmedling av mönsterförlagor för stickning och virkning: Medierna, marknaden och målgruppen i Sverige vid 1800-talets mitt. Stockholm: Gidlunds förlag, 2021.

- Bagherius, Henric. Korsettkriget. Modeslaveri och kvinnokamp vid förra sekelskiftet. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, 2019.

- Ballaster, Ros, Margaret Beetham, Elizabeth Frazer, and Sandra Hebron, Women’s Worlds: Ideology, Femininity and the Woman’s Magazine. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1991.

- Bayuk Rosenman, Ellen. “Fear of Fashion; Or, How the Coquette Got Her Bad Name.” ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes & Reviews 15, no. 3 (2002): 12–21. doi:10.1080/08957690209600070.

- Beetham, Margaret. A Magazine of Her Own? Domesticity and Desire in the Woman’s Magazine 1800–1914. London and New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Bland, Sidney R. “Shaping the Life of the New Woman: The Crusading Years of the Delineator.” American Periodicals: A Journal of History, Criticism, and Bibliography 19, no. 2 (2009): 165–188. doi:10.1353/amp.0.0030.

- Boardman, Kay. ‘A Material Girl in a Material world’: The Fashionable Female Body in Victorian Women’s Magazines.” Journal of Victorian Culture 3, no. 1 (1998): 93–110. doi:10.1080/13555509809505913.

- Bohleke, Karin J. “Americanizing French Fashion Plates: Godey’s and Peterson’s Cultural and Socio-Economic Translation of Les Modes Parisiennes.” American Periodicals: A Journal of History, Criticism, and Bibliography 20, no. 2 (2010): 120–155. doi:10.1353/amp.2010.0006.

- Breward, Christopher. “Femininity and Consumption: The Problem of the Lage Nineteenth-Century Fashion Journal.” Journal of Design History 7, no. 2 (1993): 71–89. doi:10.1093/jdh/7.2.71.

- Buxton, Hilary. “Health by Design: Teaching Cleanliness and Assembling Hygiene at the Nineteenth-Century Sanitation Museum.” British Journal for the History of Science 51, no. 3 (2018): 457–485. doi:10.1017/S0007087418000493.

- Byler, Lauren. “If the Shoe Fits … Trollope and the Girl.” Novel: A Forum for Fiction 42, no. 2 (2009): 268–277. doi:10.1215/00295132-2009-014.

- Carter, Keryn. “Consuming the Ballerina: Feet, Fetishism and the Pointe Shoe.” Australian Feminist Studies 15, no. 31 (2000): 81–90. doi:10.1080/713611928.

- Chen, Eva. “Its Prohibitive Cost: The Bicycle, the New Woman and Conspicuous Display.” Journal of Language, Literature and Culture 64, no. 1 (2017): 1–17. doi:10.1080/20512856.2016.1221620.

- Da Vinci, Leonardo. “Human Proportions.” In Edward MacCurdy, ed., The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Arranged, Rendered into English and Introduced by Edward MacCurdy. New York: George Braziller, 1955.

- Díaz Cornide, Martina. La Belle-Époque des amours fétichistes. Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2019.

- Fields, Jill. “‘Fighting the Corsetless Evil’: Shaping Corsets and Culture, 1900–1930.” Journal of Social History 33, no. 2 (1999): 355–384. doi:10.1353/jsh.1999.0053.

- Fischer, Gayle V. Pantaloons and Power: A Nineteenth-Century Dress Reform in the United States. Kent: The Kent State University Press, 2001.

- Gedin, David. “Att få lov. Kvinnor och baler kring 1880-talet.” Samlaren 128 (2007): 52–107.

- Gustafsson, Karl Erik, and Per Rydén. Den svenska pressens historia. II. Åren då allting hände (1830–1897). Stockholm: Ekerlids förlag, 2001.

- Helmius, Agneta. Mode och hushåll. Om formandet av kön och media i frihetstidens svenska små- och veckoskrifter. Uppsala: Uppsala universitet, 2022.

- Hilborn, Emma. “Den eleganta cyklisten: Cykling, mode och kvinnlighet i sekelskiftets svenska och danska damtidningar.” Historisk tidskrift 138, no. 1 (2018): 3–32.

- Jenkins, Emily. “Trilby: Fads, Photographers, and Over-Perfect Feet.” Book History 1, no. 1 (1998): 221–267. doi:10.1353/bh.1998.0008.

- Julia, Christie-Robin, Belinda T. Orzada, and Dilia López-Gydosh. “From Bustles to Bloomers: Exploring the Bicycle’s Influence on American Women’s Fashion, 1880–1914.” The Journal of American Culture 35, no. 4 (2012): 315–331. doi:10.1111/jacc.12002.

- Korte, Barbara, and Stefanie Lethbridge. “A Wreath of Freedom and Control: The Kränzchen Periodical for Girls in Late Nineteenth-Century Germany.” Victorian Periodicals Review 53, no. 4 (2020): 559–582. doi:10.1353/vpr.2020.0049.

- Ladd Nelson, Jennifer. “Dress Reform and the Bloomer.” Journal of American & Comparative Studies 23, no. 1 (2000): 21‒25. doi:10.1111/j.1537-4726.2000.2301_21.x.

- Larsson, Lisbeth. En annan historia. Om kvinnors läsning och svensk veckopress. Stockholm/Stehag: Symposion bokförlag, 1989.

- Manne, Kate. Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. London: Penguin Random House, 2019.

- Marcus, Sharon. “Reflections on Victorian Fashion Plates.” Differences 14, no. 3 (2005): 4–33. doi:10.1215/10407391-14-3-4.

- Mesch, Rachel. Having It All in the Belle Epoque. How French Women’s Magazines Invented the Modern Woman. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

- Moruzi, Kristine. Constructing Girlhood Through the Periodical Press, 1850–1915. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Perrot, Philippe. Fashioning the Bourgeoisie. A History of Clothing in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Ribeyrol, Charlotte. “Poetic Podophilia: Gautier, Baudelaire, Swinburne, and Classical Foot-Fetishism.” Journal of Victorian Culture 20, no. 2 (2015): 212–229. doi:10.1080/13555502.2015.1021536.

- Ribeyrol, Charlotte. “‘The Feet of Love’: Pagan Podophilia from A.C. Swinburne to Isadora Duncan.” Miranda 11, no. 11 (2015): 1–13. doi:10.4000/miranda.6847.

- Runefelt, Leif. Att hasta mot undergången. Anspråk, flyktighet, förställning i debatten om konsumtion i Sverige, 1730–1830. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2015.

- Runefelt, Leif. Den magiska spegeln. Kvinnan och varan i pressens annonser 1870–1914. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2019.

- Runefelt, Leif. “The Corset and the Mirror. Fashion and Domesticity in Swedish Advertisements and Fashion Magazines, 1870–1914.” History of Retailing and Consumption 5, no. 2 (2019): 169–193. doi:10.1080/2373518X.2019.1642566.

- Runefelt, Leif. “Modedockan.” In Historiska typer, edited by Peter Josephson and Leif Runefelt, 247–266. Stockholm: Gidlunds förlag, 2019.

- Semmelhack, Elizabeth. “A Delicate Balance: Women, Power and High Heels.” In Shoes: A History from Sandals to Sneakers, edited by Giorgio Riello and Peter McNeil, 224–247. Oxford: Berg, 2006.

- Shawcross, Rebecca. “High Heels.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valeries Steele, 308–309. Oxford: Berg, 2010.

- Sigurd [Alfred Hedenstierna]. Fröken Jennys konditioner. Berättelser, skizzer och humoresker. Stockholm: Hugo Gebers förlag, 1893.

- Steele, Valerie. Fetish: Fashion, Sex and Power. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Steele, Valerie. “Shoes and the Erotic Imagination.” In Shoes: A History from Sandals to Sneakers, edited by Giorgio Riello and Peter McNeil, 250–270. Oxford: Berg, 2006.

- Steorn, Patrik. “Konstnärligt antimode. Svensk reformdräkt kring sekelskiftet 1900.” In Mode – en introduktion. En tvärvetenskaplig betraktelse, edited by Dirk Gindt and Louise Wallenberg, 225–249. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2009.

- Summers, Leigh. Bound to Please. A History of the Victorian Corset. Oxford & New York: Berg, 2001.

- Svenska Akademiens Ordbok. Stockholm: Svenska Akademien, 1906.

- Törnvall, Gunilla. “From Paper Patterns to Patterns-On-Fabric: Home Sewing in Sweden 1881–1891.” Costume 57, no. 1 (2023): 55–81. doi:10.3366/cost.2023.0245.

- van Reemortel, Marianne. “Women Editors and the Rise of the Illustrated Fashion Press in the Nineteenth Century.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 39, no. 4 (2017): 269–295. doi:10.1080/08905495.2017.1335157.

- Walsh, Margaret. “The Democratization of Fashion: The Emergence of the Women’s Dress Pattern Industry.” Journal of American History 66, no. 2 (1979): 299–313. doi:10.2307/1900878.

- Wyngaard, Amy S. “The Fetish In/As Text: Rétif de la Bretonne and the Development of Modern Sexual Science and French Literary Studies, 1887–1934.” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 121, no. 3 (2006): 662–686. doi:10.1632/003081206X142814.