ABSTRACT

This article maps out the largely unknown history of poor women’s dealings with coffee in Stockholm during the coffee prohibitions of 1794–1796 and 1799–1802 drawing on the city’s extensive police records. A total of 536 cases have been identified that involved the illegal selling, preparation, and consumption of coffee. These cases are analysed in the context of the separate but intertwined research fields of the global underground, household work, and the consumption of new exotic goods in the early modern period. The results from the study reveal the complex networks that facilitated the trade in coffee beans and coffee beverages during the prohibition, and the multifaceted processes which promoted the status of coffee to a common consumer good. It also reveals the extent to which coffee brought labour opportunities and income to poor women, but also how, by the end of the eighteenth century, the consumption of coffee had gained new connotations associated with work and leisure.

JEL CODES:

1. Introduction

When she was arrested, the 18 pounds (7,7 kg) of coffee discovered at the dwellings of Maria Kiempe in October 1794 would form only one part of the evidence used against her in Stockholm Police Court. Another would be her own admission that she had sold a variety of beans and coffee surrogates as well as the beverage itself. In her own defence, an emotional Kiempe referred to her ill health and destitution; coffee peddling was the only means by which she could escape ‘the utmost wretchedness’.Footnote1 But the police court rejected her pleas for mercy and found Kiempe guilty of having breached ‘the gracious regulation of opulence and abundance’ law of 1794, a sumptuary decree prohibiting the retail, preparation, and consumption of coffee. This was one of several coffee bans introduced in the long eighteenth century, whose aim was to improve the state’s finances by reducing the import of exotic luxuries. Mercantilism thus provided the economic framework for the bans, and reflected the specific situation of Sweden, a country with no significant colonial holdings, a circumstance that set it apart from the main European trading nations of the time (Magnusson, Citation1987).

As the bans also indicate, Swedes did have a taste for coffee, a taste they shared with the rest of Europe. The surviving police registers, protocols from court proceedings, and pardon applications from the prohibition periods offer more specific insights; namely, evidence of an urban underground coffee-culture which to a large extent was populated by poor and insubordinate women, like Kiempe. The aim of this article is to map out these women’s roles in the retailing, preparation, and consumption of coffee in Stockholm in the 1790s and early 1800s, drawing on the unique material produced by the city’s police. In doing so we reveal that poor women’s dealings with coffee were intricately connected with their work and leisure. Moreover, we show how coffee beans and consumer habits intertwined in many complex and multidirectional processes during the prohibitions, indicative of how coffee became a common consumer good in Sweden.

The article is divided into three parts – selling, preparing, consuming – each relating to separate but intertwined fields of research: the global underground, household work, and consumption. Coffee actually takes centre stage in many histories of globalisation. Together with tea and sugar, it was one of the key commodities that fuelled the boom in long-distance trade in the eighteenth century (Pomeranz & Topik, Citation2013). The expansion of global trade also led to attempts to try to control it; however, such attempts only resulted in the creation of what Michael Kwass (Citation2014), in his study of smuggling in eighteenth-century France, has termed a ‘global underground’. Research from France has shown that women from various socioeconomic backgrounds played a key role in enabling and maintaining this global underground (Montenach, Citation2017). This was also true in Sweden, where the coffee bans, repeatedly issued during the eighteenth century, encouraged smuggling and the rise of a black market (Knutsson, Citation2019).

As Olwen Hufton and others have argued, women’s involvement in illegal activities, particularly economic crimes, was often linked to life-cycle changes and periodic poverty (Hufton, Citation1984; King, Citation1996; Lane, Citation1997; Boulton, Citation2000; Kilday, Citation2014). Indeed, Anne Montenach has suggested that involvement in illegal trade was most often a fall-back plan, an add-on to legal forms of employment during periods when financial need was particularly pressing (Montenach, Citation2015a). Widowhood has been identified as a particularly trying period for women, who became increasingly involved in criminal activities because they needed to provide for themselves and, often, their underage children. Women could easily become economic victims during the early modern period when their informal income-generating activities began to be regulated and criminalised (Lane, Citation1997). However, prohibitions could also open up new survival strategies. When trade went underground, regular checks and guild affiliations no longer held sway, allowing anyone willing to take the risk to participate in illicit trade (Knutsson, Citation2019). Businesses could, if they remained clandestine, be considerably freer in their activities than established legal ones, which suffered constant surveillance by the authorities (Ling, Citation2016; Knutsson, Citation2019). Several scholars have thus pointed to the importance of considering illegal sources of income as part of female survival strategies, and Penelope Lane (Citation1997) has encouraged researchers to consider not only how many women appear in the crime statistics, but how and why women turned to crime. The first part of this article comprises just such a study.

Another way in which the demand for coffee came to impact the life and labour of women relates to the work of turning beans into a beverage. Before the modern retail practice of selling pre-roasted and ground coffee, coffee beans were largely sold raw and their preparation into a drink was a household chore. This is one example of how household work has changed throughout history, and marks an important point of departure in recent research into how women contributed to early modern economies in England and Sweden, as developed by historians such as Jane Whittle and Maria Ågren and their research teams (Ågren, Citation2017; Whittle, Citation2019; Whittle & Hailwood, Citation2020). In their studies they extracted data from a wide range of sources, including juridical material, focusing on verbs that tell stories of work, such as what tasks women and men performed, rarely or regularly, and how women interacted with different sectors of the economy (Ågren, Citation2017; Whittle & Hailwood, Citation2020). They have also shown how gender, civil status, and positions within households, the central unit of labour in the early modern period, determined how chores were divided. Married women in early modern households, for example, tended to do more skilled chores associated with higher status (Ling et al, 2017).

Such an approach to gender and work in history can further be combined with studies by Sara Pennell that focus on different household spaces, including the kitchen, and how the work that took place there, shaped hierarchies, particularly the relationship between maids and mistresses (Pennell, Citation2012a; Pennell, Citation2012b). Yet to many, although not all, early-modern maids, such hierarchies only shaped part of their working lives. Many women participated in the practice of life-cycle servitude, which entailed spending the beginning of their working life in servitude prior to getting married and setting up their own households (Whittle, Citation2017). Making use of the verb-based method, tracing words such as roasting, grinding, and cooking, in the legal material and mapping them onto the history of the hierarchical household and life-cycle servitude, enables us to uncover the extent to which coffee-related work had become part and parcel of maids’ everyday work. These aspects are discussed in the second part of the investigation, covering coffee preparation crimes. Here we also offer a hypothesis for how coffee drinking habits spread, which problematises the ‘trickle down’ theory of consumption (McKendrick,Citation1982). We suggest that skills and developing tastes were key aspects acquired during life-cycle servitude, as was the relocation of maids as they moved from households in which they served to households of their own during their lifetimes.

Poor people’s consumption practices are otherwise notoriously hard to get at. Traditionally this has been done by studying the often brittle remains of material culture. Researching probate inventories, Anne McCants (Citation2008) has, for example, shown that global consumer wares were far more widespread among the Amsterdam poor in the eighteenth century than previously believed, challenging the idea that coffee and tea were luxury products. Similar studies have been done on Swedish probate inventories, suggesting that coffee paraphernalia first spread among the middle classes in the cities in the eighteenth century, but were only intermittently found in the countryside and among the lower echelons of society. This has led to the conclusion that coffee drinking was not common in the countryside or among the lower sorts until the 1820s and 1830s (Ahlberger, Citation1996; Hallén, Citation2009). But, although this assumption has since been challenged, no systematic attempts have been made to study coffee drinking among non-elites in eighteenth-century Sweden (Runefelt, Citation2015). In our study we show that coffee consumption was widespread in Stockholm around 1800, in spite of the economic downturn that the people of this ‘stagnating metropolis’ experienced. (Söderberg, Jonsson, & Persson, Citation1991). Moreover, we demonstrate that it was actually prevalent among poor female consumers, who drank coffee in small, intimate domestic contexts, or even alone.

In this respect, the results from the article offer an important contribution to the long history of how and why consumers started to demand the sorts of global consumer goods which eventually became an integral part of European every-day life. Research by historians such as Woodruff Smith and others has shown how these goods, tea and coffee in particular, came to play a central role in the performance of respectable identities in different cultural contexts, such as the coffee house or in the domestic setting (Smith, Citation2002). The main actors in this type of analysis have typically belonged to a new elite, the middling classes of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe. Poorer consumers, by contrast, have received not only less but also different types of scholarly attention. Jan De Vries has, for example, studied how their work patterns changed as their demand for new goods evolved – as they, in De Vries’s words (2008), became more ‘industrious’. Others, most famously Sidney Mintz, have discussed how sugar and caffeinated drinks were added to the menus of the ‘industrial canteens’ and thus introduced into the diet of the British working class (Mintz, Citation1986). However, as Laurence Klein (Citation1995) has argued, we should be wary of creating a dichotomy between consumption for utility and for politeness (respectability). Instead of thinking of them as contrasting incentives for consumption, he suggests that we should view them as complementary.

Our study shows that the home and the family were critical cultural contexts for poor women’s coffee consumption, just as they were for more elite women. However, the police materials show that coffee was an important component in other cultural contexts too, such as places of work and female-only leisure time. The contours of the contexts that can be derived from these judicial materials are perhaps the most important results informing this study, as they point towards the different roles that the consumption of coffee came to play in the shift between the early modern and modern world.

1.1. The coffee bans

Coffee was banned in five separate periods between the 1750s and the 1820s: 1756-61, 1766-69, 1794-6, 1799–1802 and 1817-1823. On the first two occasions only coffee was banned, but in the latter three coffee surrogates were also banned. The bans were steeped in a patriotic discourse that encouraged the population to turn their back on coffee for the good of the country and its allies. Unpatriotic members of the public convicted of coffee crimes would have their names published in the newspapers (Knutsson, Citation2019). Behind this patriotic rhetoric and the many other justifications given for the bans, the essential motivation was economic: an attempt to reduce the international trade in coffee and to guarantee autarky in the face of Sweden’s failed attempts to secure its (coffee) producing colonies and to defend against ungovernable global influences (Knutsson, Citation2019). This issue became more pressing as the market for coffee expanded and reached increasingly ‘problematic’ consumers: that is, people from the lower echelons of society who challenged established norms with their consumption. While statistical studies of Scandinavian importation have suggested that global wares like coffee and sugar only became common consumer goods after the 1830s (Rönnbäck, Citation2010), work on smuggling in the eighteenth century has shown that the contraband trade was more extensive than previously believed, at least in Sweden (Knutsson, Citation2019). Coffee was the second most smuggled contraband ware in Sweden, and between the early bans in the 1760s and the 1790s coffee smuggling became more professionalised and was conducted on a larger scale.

Contravening the coffee bans was also, like smuggling, regarded as a threat to state finances, something which also explains the high fines levelled on the culprits. There were three types of coffee crimes: selling coffee, punished with a fine of 50 rdr (riksdaler); making coffee, with a fine of 10 rdr; and drinking coffee, with a fine of 2 rdr. 50 rdr roughly equated to 5 months’ work for an able seaman, or 261 days income for an unskilled labourer, an eye-watering sum (Lagerqvist, 2005; Söderberg, Citation2010). This can be compared to another illegal venture common in the police records, selling illegal alcohol, a crime punished with a fine of 16 rdr 36 sk (skilling) (1 rdr = 48 sk). Coffee crimes had higher fines than any other crime handled by Stockholm’s Royal Police Chamber (Äldre Poliskammaren), founded in 1776, which primarily dealt with threats to public order, misdemeanours and petty crime (Jarrick & Söderberg, Citation1998; Larsson, Citation2016; Osvald Citation2022). The size of the police force varied, growing from 50 to 70 constables between 1782 and 1812, with around 10 supervising constables (Staf, Citation1950). In theory, police officers were expected to demonstrate a high level of integrity. According to the regulations, any officer bearing false witness or submitting erroneous reports was punished with penal service (Larsson, Citation2016; Osvald Citation2022). In practice, however, conflicts of interest, bribery, and personal animosity still influenced police work.Footnote2 Police officers received a third of the fines from any crime they reported that resulted in conviction, and consequently they had a personal interest in reporting as many crimes as possible. The police were mainly concerned with controlling and monitoring the lower social classes of Stockholm, something that is very apparent in the police office records (Larsson, Citation2016; Osvald Citation2022). It is worth stressing, then, that due to the police force’s preoccupation with the lower echelons of society, the material evidence used in this paper is not appropriate for researching elite coffee consumption. What it does reveal is something usually much harder to get at – opening up the coffee market to reveal a previously hidden group, the non-elite female consumers, makers, and retailers of coffee.

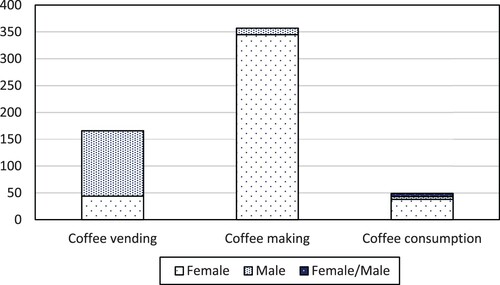

This article will consider coffee-related crimes during the prohibition periods 1794–96 and 1799-1802. By examining the period after the foundation of the Royal Police Chamber, we can draw on the new body of source material these records produced in the shape of police diaries, registers, and protocols, which make up the spine of the study. In total, 536 criminal cases have been identified in the police registers, 129 from the first period and 407 from the second. These registers have been supplemented with other surviving legal materials such as protocols, memorandums, and appeals, as well as tax registers, bankruptcy records, and trading licenses. A rough breakdown of the cases can be found in , which gives a general idea of the nature of the coffee crimes reported to the police office. However, some of the cases involved several crime classifications and occurred more than once.

2. Underground coffee: illegal survival strategies

Coffee first arrived in Sweden in the 1680s. Throughout the early decades, the retailing of coffee followed a similar trajectory to that in many other European countries: coffee, initially considered a medicine, was first sold by apothecaries, but the business was slowly transferred to grocers (kryddkrämare). These two male-dominated groups typically argued over who should have the license to sell what goods (Hjelt, Citation1893). Although little is known about how coffee beans were traded outside the prohibition periods, the grocers were dominating the urban legal trade by the end of the eighteenth century. Coffee houses were also established in urban centres such as Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Turku (Åbo). From the 1740s women began to play a more visible role in running the coffee houses in Stockholm, as licenses were granted for running coffee houses as forms of charity. Regulations from this time stipulated that 20% of all coffee house licenses (5 of 25) issued by the city governance were to be earmarked for poor women (Bolin, Citation1944). Poor women’s right to run coffee houses was part of a larger social phenomenon whereby women were given trading rights, particularly in the catering industries, as a form of poor relief (Bladh, Citation1991; Ling, Citation2016).

While this local circumstance can to some extent shed light on why, when the coffee bans were introduced, poor women in Stockholm were ready to participate in, and benefit from, illegal coffee retailing, it is also worth considering other more general explanations for their willingness to break the law. Results from research on early modern France, for example, have shown that women, especially financially exposed and single women, often turned to the black market as part of their makeshift survival strategies and played a crucial role in perpetuating illegal trades (Hufton, Citation1984; Montenach, Citation2015a; Montenach, Citation2015b). As we will show below, similar strategies can be detected in Stockholm’s underground coffee-culture. During the first period considered here, 1794-6, there were 9 cases in the police records involving female coffee vendors, which equates to 6% of all cases reported for this period. In the second period there were 35 cases involving women selling coffee, or 8.3% of all cases. It is important to note that the remainder of coffee vendors in the police registers, 24% of all cases in the first period and 22% in the second, were male grocers who in legal times had enjoyed a virtual monopoly on coffee beans. Grocers clearly continued to sell coffee beans during the prohibition era under various guises; however, this trade was put under pressure by police officers, who particularly targeted their shops. This clamp down on grocery shops opened up the market to new actors, and they were almost exclusively female. In order to understand the actions of these the female coffee retailers, this survey will first consider their socio-economic lives before focusing on two types of sellers, those selling coffee beans and those selling the prepared beverage.

2.1. The socio-economic lives of coffee peddlers

Across all of the 44 cases involving female retailers, 45 individual culprits can be identified. In 5 of the cases numerous different offenders were involved and 5 culprits appear more than once. Out of the 45 identified female coffee vendors we have been able to satisfactorily track down and identify 25 women in other related materials. For the remainder, our knowledge is restricted to their names, their relational titles, and their marriage status. At the time of their arrest the vast majority of the women appear to have been poor, either chronically or temporarily. The single largest group of female coffee retailers is made up of 12 very poor women (see ). Their socioeconomic status has been established partly through the police records – women unable to afford their fines who had them converted into prison terms, with 8–28 days on bread and water depending on the perceived severity of the crime,Footnote3 or who were released without punishment – and partly through the tax registers, which use the term destitute (utfattiga) for those unable to pay their taxes.Footnote4 During the second prohibition period the court and the police began to show mercy for the impoverished women caught selling coffee. Instead of converting the fines to a prison sentence, many women saw their fines commuted when they were unable to pay.Footnote5

Table 1. Suspected female coffee retailers in the police registers 1794–1796 & 1799-1802.

Focusing on these poor women allows certain patterns to emerge that help explain why they became involved in the illegal coffee trade. A representative example is Anna Elisabeth Mangeot, wife of the elderly girdle-maker apprentice Carl Mangeot. She was first caught selling coffee in 1800 at the age of 56. In the tax registers, Mangeot and her husband are described as destitute, living in crowded quarters with their two underage children. Due to her extreme poverty, she was not sentenced with the customary 50 rdr fine but was instead given a sharp warning to end her illegal trade. The warning appears to have had little impact on Mangeot; the following year, after being widowed, she was again caught, but her fine was commuted due to poverty.Footnote6 Mangeot is notable in that she appears in the registers once as married and once as widowed; however, as shows both married and unmarried women are common in the police registers.

It seems, then, that poverty appears was a central factor motivating women to sell coffee during the prohibition periods, even though we know the fines for doing so were very steep. While there were married women selling coffee, the majority of the culprits were single females, and this is likely linked to the fact that single women were particularly vulnerable to economic hardship. This was especially true for widows who might also be providing for underage children.Footnote7 Indeed, providing for children was the reason many women gave for engaging in coffee retailing. It also correlates with research on other types of female crime, such as petty theft and prostitution, which were particularly common among lone women, especially widows with children (King, Citation1996; Lane, Citation1997). It is therefore not surprising that two thirds of the women engaged in coffee vending during the prohibitions were ‘women without men’.

The poverty experienced by these women did not necessarily mean destitution, as it could also be status or estate-related poverty, i.e. they were poorer than their social standing demanded (Hassan Jansson, Citation2009). The most illustrious woman found in the records to have been retailing coffee was the divorced baroness Beata Rehbinder (née Rutenskiöld), who was involved in coffee crimes on three occasions between 1800 and 1801.Footnote8 Rehbinder had separated from her husband in 1790, and had since then lived alone in a few rooms in central Stockholm with a maid. She received a small yearly payment of 166 rdr from her former husband. This sum could not even cover her yearly rent of 232 rdr. It seems highly plausible that this contributed to Rehbinder’s decision to start selling coffee. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to establish if this was a longstanding practice or something the baroness took up during the prohibition period, when the illegal coffee market offered opportunities for black market entrepreneurs. When Rehbinder died in 1804, at the age of 38, she left behind a considerable assortment of equipment for preparing and serving coffee and tea.Footnote9 Rehbinder thus appears to have made use of the tools at her disposal to further her insufficient income.

While some women appear to have turned to coffee vending during times of particular economic distress, for others it was a long-term support strategy. This can be seen not merely in the cases of repeat offenders but also in the women’s statements to the police.Footnote10 When the police widow Anna Margareta Källander was caught in her lodgings with two large coffee pans, she explained that she had made a living for some time by selling coffee.Footnote11 Coffee retailing, for both women and men, had a considerably higher rate of reoffending than any other type of coffee crime. This is not necessarily a sign of an increased likelihood to reoffend compared to coffee making; for example, the greater number of arrests for retailing could simply be linked to more focused police surveillance.Footnote12 What it does show, however, is that there were women who engaged in coffee retailing over extended periods of time, sometimes years, despite the risks involved. The most notable example of this is the seiner’s wife Catharina Wennman, who was first caught selling coffee in August 1799 – not even a month after the reintroduction of the coffee ban.Footnote13 Despite being charged 50 rdr for her illegal trading, Wennman was caught again in 1801 and again in 1802.Footnote14

In fact, women had long been involved in retailing, a reflection of the two-support system common in Sweden at the time, which meant that a household needed income from both the husband and the wife to stay afloat (Ling et al, 2017). This meant that many women were running businesses, such as baking, brewing, vending, and serving, alongside their household duties. The police records show that selling coffee was one of the many side ventures women engaged in, either selling coffee beans or selling the prepared beverage at their taverns, public houses or chophouses.Footnote15 It is possible that the prohibition periods amplified this trend as the coffee trade went underground, thereby diverting it, at least partially, from its regular supply channels. However, testimonies given by the female vendors indicate that at least some of them had been trading coffee even prior to the bans. Whereas for male grocers, their official business ventures required the permission of societies and guilds, for women, illegal vending was something that could be picked up by anyone at any time without overcoming bureaucratic hurdles or risking financial exposure. The difference between female (unlicensed) and male (licensed) coffee vendors is also noticeable in relation to the fallout of their crimes. Women involved in retailing were often directly punished; grocers, by contrast, hid behind their staff, particularly their ever-changing shop assistants, claiming complete ignorance while their 50 rdr fines were either rapidly paid or contested in court. They were neither poor nor socially exposed but rather part of a bourgeois elite, and were not intimidated by the patrolling police.

2.2. Selling beans

Cases in the police records of women selling coffee beans can roughly be divided into two categories, women selling coffee beans under the counter in their shops and women without an official trade selling out of their homes. The women who sold from shops were primarily wives and widows of grocers, who during legal times were tasked with selling coffee, but they also included some other types of shop owners, such as silk and accessory retailers.Footnote16 We can here presume that these retailers, particularly the grocers’ widows, had access to the beans through the legal supply chains during legal times and kept selling during the prohibition periods.

By contrast, the women selling from home would have accessed the beans through other channels. It is especially noteworthy that a considerable number of women selling from home were connected with men who worked (or had been working) in law enforcement (5) or as seafarers (6).Footnote17 Clara Finneman, widow of the Director General of the Customs Office, had, for example, maintained contact with the customs office following her husband’s death, as her eldest son was also working there. It is possible that she acquired the beans that she vended through the customs office, which had a large contraband storage facility in Stockholm.Footnote18 This sort of corruption within the customs office was not uncommon, and confiscators are known to have spirited away contraband from their seizures (Knutsson, Citation2019). In regard to the seafarers it seems likely that the women’s coffee retailing was related to the long tradition of sailor and fishermen smugglers who played a crucial role in bringing in coffee during prohibition eras both for themselves and others (Knutsson, Citation2019).

For the women selling coffee in their private lodgings the informal environment did not mean that they were lacking the tools of their trade. Coffee beans might be squirrelled away in baskets and chests, tucked away under beds or hidden in basements, but the retailers were still equipped with scales to measure out the coffee and paper cones to package it in.Footnote19 The size of their coffee stocks varied. Wennman was found to be in possession of 8 ¼ pounds (c. 3.5 kg) of coffee beans, while one of the most prolific coffee vendors, Maria Kiempe, stocked 18 pounds (c. 7.7 kg) of regular coffee beans, but also offered chicory root, roasted beans, and sugar, along with brewed coffee ready to drink.Footnote20 Wennman’s stock would have been enough for roughly 67 cones of coffee, and Kiempe’s 148. The police records indicate that a paper cone often contained c. 4 lots, equal to 52 g of coffee. This shows that the female coffee retailing business bore many of the hallmarks of the regular retailing trade and, even though it was mainly conducted from the home, it was professionalised and conducted on a fairly large scale.

How much this coffee fetched depended on the price set by the retailers, the date, and the type. There are, however, some price indications found in the material. In 1795 the trader’s widow Maria Alén charged 40 sk per pound of coffee, while in 1799 Catharina Wennman charged 1 rdr 12 sk per pound, and the following year Anna Mangeot charged 12 sk for 4 lots of coffee, corresponding to an impressive 2 rdr per pound.Footnote21 Drawing on the prices charged by Wennman, her stock of 8 ¼ pounds of coffee would have fetched 10 rdr on the black market. This equates to a month’s salary of an able seaman, but would only have covered a fifth of her fines (Lagerqvist, Citation2015). While coffee was not prohibitively expensive, it was expensive enough to be a lucrative source of income as a semi-luxury good that could be consumed by the popular masses. Indeed, the very fact that it was possible to use coffee vending as an alleviator of hardship indicates a widespread demand for coffee despite the prohibitions.

2.3. Selling the beverage

Coffee was not just sold as beans but also in liquid form. This crime incurred a fine of 20 rdr, somewhat lower than selling beans. The police records indicate that coffee was served in three main settings, each catering to a slightly different clientele. The first was established public houses, taverns, inns, and chophouses.Footnote22 These commercial venues catered mainly for male consumers; on the rare occasions we get a glimpse of these patrons they are exclusively male: sailors, a captain, and coachmen.Footnote23 These establishments most likely also served coffee during legal times, and continued to do so despite the bans. They bear some similarities to the early eighteenth-century Swedish coffee houses that were run by women but frequented by men. Interestingly, no illegal trading of coffee in any establishment referred to as a coffee house is registered in the police records during the prohibition periods researched here. It is likely that their trade in alcoholic drinks kept them in business. Judging by advertisements in the Stockholm newspapers they also offered meeting rooms for different types of businesses, such as firms concerned with, for example, bankruptcy cases, on a regular basis.Footnote24

That alcohol and coffee were sold together in various different English establishments, and that such establishments were bawdy places to visit, has been discussed by Phil Withington (Citation2020). Something similar was the case for one specific context for illegal coffee retailing: the late-night dance. In 1796 Anna Lisa Salander sold coffee in her public house while hosting a night-time ‘dance’.Footnote25 Similarly, the destitute curate’s widow Helena Unge, the maiden Sophia Söderström, and the seiner’s wife Lindström, all organised dances in their own rooms, where they also offered coffee for sale throughout the night.Footnote26 It is very likely that these women also sold alcohol, and probably also sex. While there are no explicit mentions of prostitution in the police material, previous research has revealed that such activities took place at events described as ‘dances’ in public as well as in semi-domestic settings in Stockholm (Bladh, Citation1997; Lennartsson, Citation2019). Following on from this, we can infer that the consumers of coffee at dances organised by Salander, Unge, Söderström, and Lindström were largely open to men.

The final settings for selling prepared coffee were small-scale business ventures run out of private lodgings.Footnote27 One of the best examples of this is Maria Kiempe. She had in her room a small set up where she roasted beans for selling and kept pans of prepared coffee ready to heat up and sell.Footnote28 She explained that her clients were restricted to ‘known’ people – people she knew. One of these clients might well have been Kiempe’s landlady, who was convicted of drinking coffee not long after Kiempe’s arrest.Footnote29 Little is known with certainty about the clients of these private coffee establishments, but it seems likely that, in contrast to the clientele of the tavern and public house, they were to a large extent female. One fairly unusual example gives us some insight into these buyers. In a small butter shop owned by Mrs. Lindberg, Catharina Gängström was found pouring boiled coffee into jugs for sale. The jugs of coffee were set out on a counter ready to be grabbed on the go, reminiscent of modern-day coffee bars. In the shop the police also found the female peddler Eva Öhman drinking coffee.Footnote30 It is probable that the consumers would have come into this space to consume the illegal coffee out of sight of the patrolling policemen; however, these do not appear to have been places intended for patrons to sit down for long periods of time. More refined coffee settings also emerge from the police material. Most noteworthy are probably the apartments of Baroness Rehbinder. It seems likely that Rehbinder, just like Kiempe, sold coffee to people known to her. However, her fine apartments and her large collection of porcelain indicate that she could offer a ‘refined’ coffee drinking experience more similar to established accounts of polite consumption.Footnote31

In this section we have shown that illegal coffee retailing was part and parcel of the survival strategies of various types of ‘poor’ and exposed or vulnerable women. As a response to an unquenchable demand, these strategies played an important role in sustaining the global underground trade in Stockholm. However, poor women’s role in sustaining the coffee drinking public went far beyond simple retailing, it extended into the heart of the household – the kitchen – where they laboured with the hands-on process of coffee preparation.

3. Coffee in the household: negotiating work and taste

The household is a focal point in the research on consumption in the early modern period, particularly in the work of British historians, who have linked material culture to the development of identities and notions of respectability and politeness among the middle classes in particular (Berg, Citation2005). Within this context, attention has been directed towards tea drinking and how rituals evolved in better-off families as acts of intimacy, rituals in which the mistress of the household could take a central role (Smith, Citation2002). The Swedish case was similar, but involved coffee consumption rather than tea. Analysis of popular culture and critical debates on the subject show that coffee became particularly associated with female urban domestic consumption among the better off in the second half of the eighteenth century, but also among less well-off female consumers (Runefelt, Citation2015). The bans on coffee are in a sense testament to this growing popularity. Whether or not the bans actually deterred consumers is much harder to say, though; research on materials such as diaries has suggested that middling and elite consumers got used to the bans and started to get together to share a drink again (Knutsson, Citation2019). It perhaps comes as no surprise, then, that the household was by far the most common crime scene in Stockholm. The act of preparing coffee therein is the most frequently reported offence, constituting roughly two thirds of all coffee cases.

A further reason for the very high prevalence of cases concerned with preparation has to do with legal considerations: the act of consuming coffee was hard to prove, whereas coffee making utensils could be used as evidence in court. From our point of view the latter evidence is helpful, as the court’s focus on grinders and pans for cooking and roasting helps to show the labour involved in producing the beverage from the raw bean found in the household. As will be discussed in more detail below, this labour was largely done by women. Of the 129 coffee crimes reported in the first period and 407 in the second, 86 (or 67%) and 259 cases (or 64%) respectively involved women making coffee. Aside from the odd individual male coffee maker, the few examples of groups of male culprits – a handful of mariners and ‘foreigners’ – suggest that men predominantly prepared coffee in homo social contexts, or when they were in transition, and thus outside of the household context.Footnote32 At home, the overrepresentation of women is thus largely a reflection of gender-based work divisions. In the first section of this part, the focus will be on the coffee-related household work conducted by women and what the material evidence can tell us about it: when coffee making took place, how it was organised, the status of the work and the skills involved. In the second section the focus will be on those doing the chores, particularly maids, and their relationship with their master and mistresses, but also on those who presumably made coffee for themselves.

3.1. Roasting, grinding and making coffee

Making coffee involves roasting, grinding, and cooking, and the police ledgers frequently contain information about what their suspect had been caught doing, or references to the equipment used, particularly during the first of the prohibition periods, and sometimes also when the chore was performed. In 68 cases both types of information are provided, enabling us to uncover a schedule of work.

clearly shows that coffee making tasks most commonly took place in the morning, followed by the afternoon.Footnote33 The results likely reflect patterns of consumption, although there is evidence, particularly from female proprietors of commercial establishments, that coffee was brewed in the morning and kept throughout the day, to be reheated on demand.Footnote34 On the premises of the tavern keeper Fredrica Lindberg, for example, the police found 7 halvstop (4.5 litres) of premade coffee.Footnote35

Table 2. Time references in cases involving coffee preparation.

Further evidence that coffee was prepared in separate stages can be inferred from the police ledgers; only a handful of cases from each period refer to more than one of the pieces of equipment used in coffee making, or to more than one of the specific chores. The case of divorced captain’s wife Gyllenskepp, in whose kitchen the police found a roaster, a grinder, and a pot of warm coffee, is a unique exception.Footnote36 By far the most frequently referred to piece of equipment is the coffee pot, mentioned in 71 cases; in more than half of these (36 in total), the police confiscated the pot, with the intention, presumably, to use it as evidence. The activity most often mentioned is ‘cooking coffee’, which appears in connection to 269 individuals, compared to 24 of roasting and 11 of grinding. This asymmetry might reflect the generic use of the term ‘cooking’, a synonym of ‘preparing’, which is also occasionally used. Cooking could also refer to the habit of recycling coffee grounds; boiling previously used grounds with water, which was a way of eking out meagre stores. Police records regularly register used coffee ground stashes, both ‘warm’ or ‘fresh’, and carefully hidden older grounds. In the case of the chophouse keeper Christina Catharina, Thim, grounds were kept in a jar on her kitchen table.Footnote37 Coffee grounds were thus valuable both as an ingredient and as evidence, although one defendant argued that coffee grounds could be kept for long periods without becoming spoiled, and that her grounds pre-dated the prohibition.Footnote38

3.2. Coffee making and the household hierarchy

Another way of thinking about coffee making chores is to consider them from the perspective of the household hierarchy. Research on household management has indicated that the matron trained her maids to perform the most labour-intensive tasks, while she kept charge of some of the more skilled tasks (Pennell, Citation2016). Maids were caught cooking coffee in 137 cases, making up the single largest group of offenders in the records. Presumably, cooking coffee was a simple, low-status task involving heating up a pot of water and adding fresh or recycled ground coffee. As suggests, the chore was most often performed early in the morning, which probably meant that it took place in conjunction with the maid’s other morning tasks, such as lighting the fire. In total, the material contains 21 references to kitchens, four to stoves, and five to tiled stoves (kakelugn). This low-status task can be compared to the chore of roasting coffee beans, arguably a more skilled activity since it involved making sure that the expensive beans, which could be irregular in size, did not burn in the process. Maids caught roasting coffee are also noticeably rare in the records: of the 23 women accused of this crime only four are referred to as maids.Footnote39 Knowledge could, of course, be transferred between high- and low-status household members. It was perhaps the skill of roasting that was being taught when the police caught the maid Anna Wahlberg in the presence of her mistress, the coach driver’s wife Catharina Hedberg, with ‘her hands full preparing coffee’.Footnote40 While no roasting pan is mentioned, the police confiscated some roasted beans as evidence.

We can also study the status of the women accused of making coffee by looking at their titles and their ability to pay the fines. summarises which women accused of making coffee had the title of maid and which were referred to as widow or wife.Footnote41 Our assumption is that the majority of maids listed below were unmarried, and that their employment was part of their life-cycle servitude. The cases involving maids are further subdivided into three groups: maids with a named employer, maids with no named employer, and maids who worked for proprietors of commercial establishments.

Table 3. Cases of maids, wives and widows accused of preparing coffee in Stockholm 1794–1796 & 1799-1802.

Starting with the latter group, it is notable that maids caught making coffee in commercial venues were generally convicted only of making coffee, not selling it, indicating their perceived role as mediators not instigators.Footnote42 Yet, although a mistress was responsible for the goings on under her roof, the hierarchy of labour allowed proprietors to distance themselves from the crime. A recurring line of defence was that the proprietor had been asleep when the coffee was made. This defence was used by the tavern keeper Lindberg, who claimed to have been unaware of the large amount of coffee that had been prepared by her maid, Anna Lisa Lagergren.Footnote43 But when Lindberg was invited to swear an oath to the effect that the coffee had not been intended for sale, she refused. Very similar circumstances can be observed in the case of Christina Widman, a maid employed at the public house of Stina Sandberg. The police entered the public house early one morning only to find Widman alone, making coffee, while her mistress was still in bed. Just like Lindberg, Sandberg later claimed that she had no knowledge of the coffee, nor had she given her permission to make it.Footnote44 In both cases the maids were used as a buffer against the police, shielding the proprietors from being fined 10 instead of 20 riksdaler. Worth mentioning is that both Lindberg and Sandberg reappear in the police registers along with several other of their maids, who were convicted of coffee making.Footnote45

The reputation of the master or mistress was also at stake, since the names of those contravening the coffee prohibition were published in a Stockholm newspaper. Previous research has shown that maids and other servants conducted business which might threaten the safety or honour of their master and mistresses (Hassan Jansson, Citation2013). Such considerations help to explain the pattern of distancing shown by Lindberg and Sandberg, a behaviour evidenced not merely among commercial proprietors but also in regular households. A case from 1796, involving no fewer than four households and four maids, is telling, in that all of the employers – a cashier, an accountant, a widowed stove maker, and a pattern designer – claimed to be ignorant of their maids’ activities, or of the pots and grinders found in their households.Footnote46 Consequently, three of the maids were fined 10 rdr each. In this and many other similar cases a subtle agreement probably existed; the maid took the blame, and, in exchange, her master or mistress paid the fines. Evidence of this system can be found in police records. Of the maids with named employers (group two in ), 67 (or 81%) paid their fines; a third of these (22 of 67) even paid the fines ‘willingly’.Footnote47

Sometimes, however, neither employer nor maid could afford to pay; in 1795 the farrier journeyman Elkenberg’s maid, Margareta Catharina Norberg, was unable to pay the fine and was sentenced to 12 days in prison.Footnote48 In four other cases the fines for employed maids were remitted either in full or in part due to sickness or poverty.Footnote49 Nonetheless, such cases are rare and the high rate of paid fines among domestic maids compared with other groups suggest that their employers generally paid up.

In the police ledgers there are also 40 cases of maids not listed as serving in a household. They contain only brief descriptions of the crimes and are harder to assess. It seems likely, however, that the great majority of these maids had employers covering for them, since 29 (or 73%) could pay their fines. The remaining 10 (25%) had their fines remitted or converted to prison terms. Without the support of an employer, the maids became economically vulnerable.

However, lack of complicity was not only dangerous for maids abandoned by their employers; a breakdown in their relationship could also threaten the employer, and research has shown that tensions between servants and employers were common (Pennell, Citation2016). In 1801, for example, the wife of a lead founder was called to answer accusations that she had ‘consumed and enjoyed coffee’ with her husband – a charge made by her maid, Brita Stina Malmström.Footnote50 The same year, restaurateur Nils Boman accused his maid, Maria Elisabeth Löfgren, of theft, which provoked her to report him and his wife for coffee drinking.Footnote51

Likewise, maids could also be exposed, particularly those who lived within their master’s household and who enjoyed only limited privacy, usually restricted to their personal locked box. This box was normally out of reach of their employer; it was a small, protected world where servants could keep their private possessions safe (Vickery, Citation2009). However, it was not beyond the reach of the police. When widow Sophia Hagberg requested the police to conduct a search of her maid Maja Öberg’s locked box they found coffee beans and stolen yarn. Öberg immediately confessed to having made and drunk coffee on occasion.Footnote52

The coffee bans thus generated re-negotiations of relationships within households. Anecdotal evidence suggests that it also impacted who drank what kind of coffee; maids who had previously settled for their master and mistress’ pre-used coffee grounds now demanded ‘good coffee’ in exchange for their silence (Colling, Citation1983). In 1805, when coffee became legal again, the famous diarist Märta Helena Reenstierna noted that her maid Lena was furious with her ‘because I had made coffee from the [used] grounds, that she tends to extract the juices from’ (Colling, Citation1983, pp. 183–184). The fact that the consumption of caffeine-rich drinks ‘above stairs’ was linked to what was going on below has been discussed in research on tea drinking in Britain, where servants recycled their masters’ and mistresses’ tea leaves (Ellis, Coulton, & Mauger, Citation2015). Such behaviour corresponds with other practices of recycling non-perishable goods, including how garments were handed down from master and mistresses to servants (Lemire, Citation2012). However, coffee was arguably a more labour-intensive beverage to produce than tea, something that suggests that the key to understanding its widespread popularity as a drink is to consider those who prepared it. A taste for coffee, as well as coffee-making skills, might have been acquired during service and brought into new social settings when maids later married and set up their own households. In this way we suggest that life-cycle servitude might have been crucial in developing skills and taste in tandem, allowing for a transfer of coffee consumption between different social settings.

3.3. Wives and widows

It is not far-fetched to think, then, that many of the married and widowed women who were caught making coffee in their own homes had once served as maids in better-off households. And the fact that coffee had moved down the social ladder in turn-of-the-century Stockholm is evident if we consider the economic status of this group of coffee culprits. As suggests, 28% of the wives, (3 + 25 cases out of 106) and 23% of the widows (3 + 10 cases out of 55) accused of coffee making ended up in prison or had their fines remitted due to poverty. The low rate of widows being able to pay the fines – 56% (30 out of 55) – is further evidence that widowhood was a particularly exposed period in a woman’s life, and also that we are dealing with a different type of household to those in which maids worked.

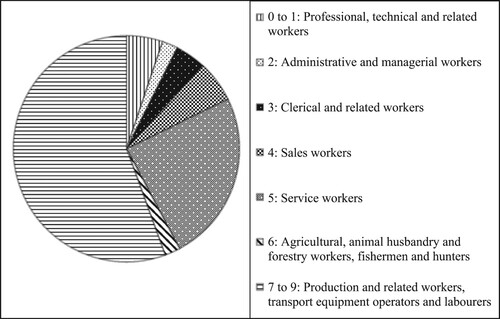

This impression is further reinforced by an analysis of the titles of wives and widows, including relational titles, i.e. to whom they were married, or occasionally who their fathers were. 134 titles can be categorised using the HISCO coding (see ). Of these, the great majority belonged to category five, ‘Service workers’ (33 women), and category eight ‘Production and related workers’ (75 women). Large subgroups are the wives and widows of porters, soldiers, textile workers, and carpenters. Moreover, among the widows and wives in our investigation, 15 were, or had been married to, journeymen, evidence of the ongoing breakdown of the traditional household centred around craft masters that marked the period. One key to this development was the growing use of remunerations to cover the cost of housing and food for journeymen (logi- and spispeng). Mats Hayen (Citation2007) points to how, through this process, public houses in Stockholm became new contact and socialisation areas for male workers, serving food and drink. For their wives and widows, consumption of coffee at home is, we argue, likely to have played a similar role promoting sociability.

Figure 2. Status of wives and widows accused of making coffee, including relational titles (HISCO). Source: Diarium, 1794–1796, and 1799–1802, Överståthållarämbetet för polisärende, Äldre poliskammaren, CIa1, vols. 21–23 and 26–29, Stockholms Stadsarkiv.

As we have shown in this section, the household is a key institution in the history of coffee, not only as a place of consumption but also one of production. How coffee was prepared reflected the hierarchical organisation of the household, but the substance itself also opened up a space for the renegotiation of relationships between servants and their master and mistresses. Moreover, skills and tastes could be transferred both within and between households, including new smaller and poorer ones, something which led to an increase of consumption.

4. Poor consumers: sociability and respite

Historians have labelled the late eighteenth century as a period of stagnation for Stockholm, when the situation of the poor population, in particular, deteriorated (Söderberg et al., Citation1991; Lindberg, Citation2007). However, it was also a period when larger households were splitting up into smaller units, when individuals in service were moving out of their places of work and setting up their own households while gaining new freedoms in regards to their consumption, particularly in terms of their diet (Hayen, Citation2007). How this combination of circumstances impacted poor people’s consumption of exotic goods in Stockholm is hard to tell. Judging by research into developments in England, sugar, coffee, and tea are likely to have been introduced into the diet of the poorer sorts as an alternative rather than as an accompaniment to traditional foods like bread, porridge, and gruel (Shammas, Citation1984). Unfortunately, we know very little about which foodstuffs supplemented the coffee taken by poor consumers. If we focus on affordability, however, it can be argued that coffee was not out of reach for individuals from the social groups at the forefront in this study, although how much coffee was needed would naturally vary depending on how strong a brew was desired and on the financial situation of the drinker. We can use both English and Swedish recipes to make the case.

In 1722, Humphry Broadbent explained in The Domestick Coffee Man that coffee-house coffee, understood to be weak and of poor quality, was made with 1 ounce of coffee (28 g) to 1 quart of water (c.1 litre), while family coffee, good coffee, was made with 2 ounces of coffee to 1 quart of water. A later Swedish recipe book suggests that for 3 cups of coffee (0.45 L), 1 lot (13 gram) of grounds would be sufficient, which corresponds almost exactly to the measurements for coffee-house coffee (Colling, Citation1983). The weaker coffee-house coffee was most likely the commonly used measurement for most coffee brewers, while richer consumers would have been able to afford stronger coffee. While the price of coffee varied, as earlier discussed, 1 lot of coffee would during the prohibition have fetched roughly 2–3 sk.Footnote53 A steep, but surmountable, price for a Swedish spinner who earned 6–7 sk a day with free lodging, but less pricy if she saved and recycled her coffee grounds (Lagerqvist, Citation2015).Footnote54 In other words, coffee drinking would have been affordable for most members of society, even if for some it would have been a rare treat, rather than a daily habit.

With this in mind, let us turn to the consumers in the police files. Cases involving consumption are considerably fewer than the production cases – possibly due to the fact that they were harder to connect to a culprit. All in all, about 52 cases contain references to coffee drinking, and there was a female presence in all but four. These include 16 (12%) of the cases from the first period and 32 (8%) of cases from the second period. By contrast, male consumers are merely involved in 7 (5%) cases in the first period and 6 (1%) cases in the second period. The great majority of the consumption cases in the police records took place in a domestic setting. In fact, there are only 5 cases involving consumption in an establishment, all but one of these involving men and/or unknown culprits. The largest group of men outside of those visiting establishments were those who drank coffee at home together with their wives, a social context which will be discussed below. The remainder of the consumers were largely female, and most of them consumed their coffee with other women.Footnote55 In the following section we will first discuss coffee consumption within the context of the family, then among friends, and finally as a solitary pleasure.

4.1. Family functions

The family was a crucial unit that consumed coffee together, and it is in this context that we also find most of our male consumers. The police registers reflect circumstances where both spouses consumed coffee together, as did mothers and daughters. The vast majority of this familial consumption took place at home, but in a notable case we find iron porter Lindström and his wife Stina brewing coffee on a dung-boat.Footnote56 On discovering spouses consuming together it was not uncommon for the husband to resist the police with bribes or violence.Footnote57 In one instance the husband did not merely attempt to fight off the police but confessed to the crime, thus shifting the blame away from his wife.Footnote58 It is seldom clear whether it was the husband or the wife who was the instigator of the coffee consumption. Not all spouses were equally complicit in coffee consumption, however, and in one unique case a husband who found his wife about to drink coffee smashed the coffee pot to pieces and denounced his wife to the authorities.Footnote59 This case is an oddity, however, and probably reflects matrimonial discord rather than a general sentiment towards coffee drinking per se.

In addition to spouses, the police records also reveal seven instances of mothers consuming coffee with children of different ages throughout the prohibition periods.Footnote60 The destitute magistrate’s widow Goldback was 64 when she enjoyed coffee together with her 15-year-old daughter Anna Christina.Footnote61 In some cases there are indications that mothers with younger children were also teaching them to drink coffee, such as the case of Brita Stina Sundberg, who was convicted of ‘allowing her child to drink coffee’, though she was pardoned due to her poverty.Footnote62 Along with their poverty, what unites these cases is that when the gender of the child is recorded, they are all female. The fact that widowed mothers and their daughters resided together is something we recognise from other studies; it was a way to save money on rent and to ensure that the household had more than one income (Hufton, Citation1984). However, as the mothers aged, new difficulties arose due to sickness and frailty, which meant that the children not merely became the main breadwinners but also had to protect and care for their mothers. In relation to coffee consumption this is evident in the case of 71-year-old tailor’s widow Elisabeth Höök, who was caught with her daughter, the sailor’s wife Lovisa.Footnote63 Elisabeth was deemed culpable for the coffee crime, and, as she was unable to pay the fine, she should have been sentenced to prison. Lovisa appears to have intervened at this point and ended up going to prison in place of her aging mother. Within both of these family settings we can discern close-knit units, consuming coffee together but also, in various ways, attempting to fend off the consequences.

It is also worth mentioning that the reoffending rate among family consumers was higher than the average. One example of this is the mother and daughter who were caught drinking coffee when the police came to announce the verdict from their previous trial.Footnote64 Coffee drinking was clearly a durable family habit that was hard to quell.

4.2. Coffee among friends

Of the 52 cases of consumer crimes that we can be certain about, 15 involved coffee-drinking friends (see ). There are examples of large gatherings, with up to four participants present;Footnote65 most coffee get-togethers were, however, intimate get-togethers of two women, such as when soldier’s wife Greta Apelgren served Catharina Toberg morning coffee in her room.Footnote66 Coffee mornings were not necessarily restricted to the drinking of coffee itself, but could involve other activities, as illustrated by the spinner Maja Burman, who visited brazier’s wife Dorothea Black to tell her fortune from coffee grounds.Footnote67 It is usually difficult to establish how the women in each case knew each other, but some appear to have been part of the same professional communities, such as the retired spinner Sara Kypert, who served coffee to the wool dyer’s wife Maja Almroth. Both women were part of a close-knit worker community at the textile factory of John Zach Tillander.Footnote68 Most relationships, however, remain shrouded in obscurity. Nevertheless, women consuming together must have served to enforce social bonds and a sense of a female community. This bonding process was most likely strengthened during the prohibition eras, as social coffee drinking made the women into criminal accomplices. Meanwhile, when a relationship turned sour, coffee could suddenly turn into a weapon. There are examples of women fighting with coffee pans and pouring hot grounds over one another; they could also denounce illegal coffee consumption to the police, thus incriminating their former friends.Footnote69

Table 4. Cases of suspected coffee drinking in the Stockholm police records 1794–1796 & 1799-1802.

Most of the women received their guests in their rooms. Their room was also their only ‘private’ space, which they could use according to their own liking and where they, at least in theory, were safe from the authorities, protected by the right to home peace. This right, which prevented authorities from searching private lodgings, was, however, revoked in 1799 in an attempt to stem smuggling (Knutsson, Citation2019). Even the right to home peace had always been qualified, though, as police officers could always enter the private rooms, particularly of poor residents, under the pretext of conducting fire checks, looking for interlopers or runaway maids, and other irregularities.Footnote70 This has probably led to an overrepresentation of these poor households in the police records.

Coffee consumption sheds light on how poor women in kitchens and living quarters created, cemented, and shattered bonds of friendship. It shows that coffee was an intricate part of their lived experience; to drink coffee together could serve as a social glue to strengthen relationships, a phenomenon that was only strengthened by the bans on coffee. Meanwhile, coffee drinking was most likely also a practice learned and circulated among poor women in such intimate get-togethers. Whether coffee was consumed among friends or in a family setting, it is notable that out of the 52 cases of consumption, 47 involved the presence of at least one other offender.

4.3. Solitary pleasures

While consuming together was common, consumers sometimes also enjoyed a steaming cup of coffee on their own. Drinking coffee in solitude was probably more common than it appears in the police registers, as it was less exposed to the dangers of denunciation than consumption, which involved several individuals. When lone consumption was exposed it was often during other police errands, such as when the police caught the carpenter’s apprentice’s wife Lovisa Westerberg ‘consuming and enjoying’ a cup of rye coffee in her room after the police accidentally entered the wrong door in search of another person residing in the building.Footnote71 Similarly, the apprentice’s widow Margareta Bröske was found making coffee one morning after patrolling police scented a coffee smell outside her dwellings. Bröske defended herself with the argument that she had felt ill that morning and unable to consume any food or any ‘stronger wares’, and so she had brewed some coffee ‘to heat myself in my wretchedness’.Footnote72 In these instances coffee appears to have been consumed as a respite from the daily toil, something that is particularly evident in the case of lackey-wife Gillberg, who was discovered sipping steaming coffee in her ‘bakehouse’ when the police came to investigate her illegal bread sales to the military.Footnote73 Drinking coffee while working, or, more correctly perhaps, while having a break from work, indicates that coffee drinking was not merely a social act but could also be a reinvigorating pause in the day of hardworking women, something Pia Lundqvist (Citation2016) has earlier observed in her study of Swedish novels from the 1830s and 40s. Such cases show that while coffee played a crucial role in social situations it was also drunk in solitude, for personal enjoyment, even among the poorer sorts, and was also connected to the idea of taking a break.

As this survey has shown, coffee was consumed by a range of poor women in Stockholm, who evidently were able to scrape together enough money to enjoy an occasional cup of coffee. In the emerging small households, the consumption of coffee could involve sociability – among family members or among friends – but it could also mark a solitary pause in the daily work.

5. New coffee trends?

By making use of unique source material generated by the Stockholm Police – as it responded to the coffee bans instituted by the Swedish government – this article has mapped out the roles of poor women in the retailing, preparation, and consumption of coffee in the capital in the 1790s and early 1800s. The results, framed by research relating to the illegal trade in global goods, on female work, and on the history of consumption, show that the life, labour, and leisure of these women were shaped by coffee in many ways. The histories uncovered are notably different from the familiar stories that typically focus on how members of the new and upcoming middle class used exotic drinks when they performed new identities in domestic settings or coffee houses in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. And so, in studying poor and disadvantaged women during the transition between the early modern and modern periods can we find evidence of how coffee became associated with new identities, performances and cultural contexts of consumption in the centuries that followed?

In the material we identified two processes which have largely gone unnoticed in previous research and which could work as starting points for further investigations into the new associations of coffee. The first concerns the results of the prohibitions themselves – the response of an early modern mercantilist state to the rising demand for an exotic imported good. In line with research on the global underground, we have found that the bans opened up retailing opportunities for poor women. However, we learned that they also generated a re-negotiation of relationships between master and servants, and possibly also between buyers and sellers, leading to a weakening of social differences, and arguably a widening division between the state and its people. It is thus possible that the coffee bans levelled the social playing field for coffee, contributing to a development in which coffee drinking became part of the performance of the people as a collective, free of state control.

The second process is not specific to the prohibition periods but relates to the role of the household as a place within which maids learned to make – boil, ground and occasionally roast – coffee, before they moved on to set up their own households into which they introduced their coffee-drinking habits. What we can detect here is not only a process of popularisation, of trickling down, but a cultural context in which coffee was becoming the drink of choice for working women. To these women, coffee was associated with work in three different ways: firstly, they had to work in order to earn a salary to purchase coffee beans; secondly, without their own maids, turning beans into beverages spelled its own kind of work; and thirdly, and following on from this, coffee drinking became a distinct break-away from their main work, an escape either in solitude, in a discrete, female-only coffee get together, or together with members of the family and household. Here we find a cultural context in which coffee drinking to working women became encapsulated in a schedule of work and leisure. As such, it points towards the central role of coffee today, as a key component of the pause we perform in the time in-between work shifts.

Acknowledgment

An early version of the paper was presented at the Gender and Work Seminar, at Uppsala University. The authors wish to thank the participants for their for helpful comments. A special thank you to Margaret Hunt and Leos Müller for reading the text and advising on the approach and the analysis. We are also very grateful for the constructive comments and criticism from our three anonymous referees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Protokoll (Askling), 1794, Överståthållarämbetet för polisärende (ÖÄPÄ), Äldre poliskammaren (ÄPK), A Ia1, vol.23, Stockholms Stadsarkiv (SSA); Memorialprotokoll (Askling), 1792–95, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, A Ib1, vol.7, SSA.

2 This was also true in relation to coffee crimes as women’s protests and appeals make clear. See e.g. Maria Catarina Hedberg, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2829, Riksarkivet (RA); Christina Hagström, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:3068, RA.

3 Diarium, 1794 vol.21, 900, 1921; Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 995; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 1281. ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

4 It should further be noted that it has not been possible to identify all of the offenders in the tax registers, we have therefore not been able to establish the socio-economic status of all of the female offenders.

5 Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 39; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 845, 1138; Diarium, 1802, C Ia1, vol.29, 32,118, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, SSA.

6 Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 39; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 1138, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, SSA; Mantalslängder, 1800, G1, BA:26, 191, Överståthållarämbetet för uppbördsärenden, Kamrerareexpeditionen, SSA.

7 See e.g. Cathrina Wennman, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2831, RA. Grocer widow Gustafva Lundberg (37) with 3 children living at home: Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 469; Widow of Överdirektör vid tullverket Carl Ludvig Finneman, (46) with 8 children living at home: Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 321, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

8 Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 297 & 975; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 1081, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

9 Beata Rehbinder, 24 april 1804, Svea Hovrätt, Adliga bouppteckningar, EIXb:169, RA.

10 Repeat offenders - Nisser: Diarium, 1795, vol.22, 693; Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 89 Cathrina Wennman: Diarium, 1799, vol.26, 714; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 978; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 181 (possibly also 110). Anna Mangeot: Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 39; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 1138. Maria Sophia/Christina Bonn: Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 1025; Diarium 1802, vol.29, 192, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA. Fredricia Lindberg, Fredrica Lindberg, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2899, RA; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 698, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

11 Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 340, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

12 This trend can also be observed among male coffee vendors, where honey traps appear to have been used to snare them.

13 Cathrina Wennman, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2831, RA.

14 Cathrina Wennman: Diarium, 1799, vol.26, 714; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 978; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 181 (possibly also 110), ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

15 Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 578; Diarium, 1799, vol.26, 714; Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 1041; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 433, 698, 911, 975, 978; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 64, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

16 Diarium, 1795, vol.22, 693; Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 89; Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 469; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 327. Silk shop: Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 693. Accessories shop: Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 1025; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 192, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

17 Law enforcement: Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 321, 481, 1335; Diarium, 1802, C Ia1, vol.29, 152, 304. Seafarers: Diarium, 1794, vol.21, 921; Diarium, 1799, vol.26, 714; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 433, 845, 975, 1103, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

18 Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 321, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

19 Diarium, 1801, vol.28, SSA, 153, 466, 1025, 1103; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 110, 181, 129, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

20 Diarium, 1794, vol.21, 900, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

21 Diarium, 1795, vol.22, 539, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA; Diarium, 1800, vol. 27, 39, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA; Catharina Wennman, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol. E2A:2831, RA.

22 Wennerholm, 22 Oct 1794, Memorialprotokoll (Askling), 1792–95, vol.7, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, A Ib1, SSA; Diarium, 1794, vol.21, 921; Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 578, 1060, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA; Fredrica Lindberg, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2899, RA.

23 Diarium, 1794, vol.21, 921; Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 578, 1060; Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 1041; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 698, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

24 Dagligt Allehanda 16th of September, 1795.

25 Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 995, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

26 Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 935; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 975; Diarium, 1802, C Ia1, vol.29, 32, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

27 Diarium, 1794, vol.21, 900; Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 975; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 340, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

28 Diarium, 1794, vol.21, 900, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA; Protokoll (Askling), Kiempe, 28 Oct 1794, 1794, vol.23, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, A Ia1, SSA.

29 Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 976, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

30 Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 322, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

31 Beata Rehbinder, 24 april 1804, Svea Hovrätt, Adliga bouppteckningar, EIXb:169, RA.

32 Diarium, 1794, vol.21, 899; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 1047; Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 99, 254; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 121, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

33 In two instances the morning time is specified to between 5 and 6 am, and 6:30 respectively. Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 836, ÖÄPÄn, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

34 Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 1060; Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 573, ÖÄPÄn, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA; Protokoll (Askling), 1802, vol.50, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, A Ia1, SSA; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 340, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

35 Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 698, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA. More information on the case can be found in Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2899, RA.

36 Diarium, 1799, vol 26, 914, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

37 Diarium, 1794, vol.21, 921; Diarium, 1795, vol.22, 516; Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 230, 725, 970; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 398, 433, 938. On Thim see Diarium, 1794, vol.23, 578, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

38 See case of Maria Catarina Hedberg, summarised in Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2829, RA.

39 Note however the terms ‘jungfru’ and ‘demoiselle’ (the latter could be used as a synonym of ‘maid’) are used for two of the 23 women. Of the remaining 17 women, 10 were married and 7 were widows.

40 Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 387, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

41 This leaves out occasional examples of women referred to with titles suggesting a subordinate position, typically associated with not being married, e.g. jungfru, hushållerska, demoiselle, and mamsell.

42 For exceptions in cases when either the proprietor was made responsible for cooking and selling or neither, see Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 1060 and Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 698, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

43 Fredrica Lindberg, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2899, RA.

44 Christina Widman, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2977, RA.

45 Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 698, 836, 1297, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA, and Fredrica Lindberg, Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2899, RA.

46 Diarium, 1796, vol.23, 592, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

47 In five cases the records even states that the employers paid, see Diarium, 1795, vol.22, 57; Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 854; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 628, 1081, 1236, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

48 Diarium, 1795, vol.22, 20; Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 280, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

49 Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 513; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 888; Diarium, 1802, vol.29, 25, 140, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

50 Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 224, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

51 Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 224, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA

52 Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 322, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

53 Diarium, 1800, vol.27, 39, 503; Diarium, 1801, vol.28, 427, 665, ÖÄPÄ, ÄPK, C Ia1, SSA.

54 The case of Maria Catarina Hedberg suggests that coffee grounds could be kept for months if not years (Nedre Justitierevisionens/Högsta domstolens arkiv, vol.E2A:2829, RA).

55 There were doubtlessly also other cases that could be included here, as the crime of consumption is not treated consistently in the police diaries and often only the coffee maker would be convicted. This is probably due to the difficulties involved in proving exactly who was going to or had just consumed. The 45 cases discussed here are those where consumption is mentioned in the police records and are not restricted to ones where consumption was punished. This allows us to include interesting and relevant materials from cases where consumption certainly was taking place.