?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The enclosure movement was a significant element of the agricultural revolution in Sweden. Legislation from 1749 onwards, opened up for Storskifte, which reduced the number of plots per owner, but did not touch the villages’ common field or housing structures. The edicts of Enskifte (1803–1807) and Laga skifte (1827), however, made possible the final dissolution of the open-field system. According to the Laga skifte legislation one single landowner applying for enclosure, could force the entire village to enclose. Nonetheless, the process was not complete even by the 1890s. Previous research has emphasised the importance of the enclosures for economic development and/or as a factor in income redistribution. It has, however, not fully explained why some villages enclosed early and others late. We investigate this question by using a newly constructed database containing all villages in the county of Västmanland. Furthermore, by using a Cox Proportional Hazards model, a random sample of 100 villages is followed over time to estimate which factors accelerated or decelerated the enclosure process. The major conclusions are that concentration of ownership and cost factors decreased the probability for enclosure while complex land-use patterns and real GDP-per capita growth increased the probability of enclosure.

1. Introduction

Enclosures in Sweden appeared in three phases. Already before 1750, some arable land was redistributed and enclosed, in order to secure correspondence between land tax burden and the amount of land owned.Footnote1 In 1749, a legislation promoting Storskifte was enacted. Storskifte implied a redistribution of plots within a village in order to reduce the number of plots for each owner, within the remaining fenced open fields. The common field structure persisted and the village still collectively determined when to sow, when to harvest, when to let the cattle go grazing. The collaboration regarding fences remained. Subsequent legislation in 1757 and 1762 gave a single applier of Storskifte within a village the possibility to force Storskifte upon resisting fellow villagers. This speeded up the process and where villages were small – for example in East Central Sweden – this redistribution reduced the number of arable plots enough to ease the rationalisation of farming, to speed up the land clearance process, to stimulate the introduction of new crops and in general to give a boost of individual entrepreneurship amongst farmers.Footnote2

In areas with large villages, for example in Western and Southern Sweden, where villages could easily comprise over 50 farmsteads each with a multitude of individual plots (or strips) located far from each other, the Storskifte far from led to this goal and further reforms were required although the number of plots per owner, was reduced to around 10–15 in general. In 1783, it was thus allowed for a villager to get his entire land cut out into one plot. These breakouts together with the full radical enclosure of entire villages owned by a few noblemen (reckoned as Storskifte if they were registered by the Land Survey Authority) paved the way for the Enskifte edict for Scania in 1803.Footnote3 According to this edict, the land surveyor should endow each villager with his entire land, including arable, meadows and pastures, in one single plot in direct connection to the farmyard. This necessitated that some landowners moved out from the villages, and so the villages were physically dispersed. Moreover, the common fields and fencing system were broken up.Footnote4

On the southwestern plain of Scania Enskifte was carried out quickly in the first decades of the nineteenth century and Sven Dahl (Citation1941) listed 316 Enskiften in Scania as a whole from 1803 to 1827, most of them occurred before 1820 and concerned villages on the plains. By 1804, a similar legislation was made for Skaraborg county in Western Sweden and by 1807 the Enskifte legislation was widened to cover the entire realm with the exception for the northernmost counties. Progress was slower outside Scania and foremost villages in the south and on the plains of Blekinge and Öland in the southeast and Skaraborg county in the west, were enclosed according to this legislation.Footnote5 For topographic reasons, Enskifte occurred rarely in East Central Sweden.Footnote6

In 1827, a new law of radical enclosure, Laga skifte replaced the Storskifte and Enskifte acts. Like the Enskifte, enclosure following the Laga skifte act broke up the old open fields system with its strips and common fences, replacing it with consolidated fields for each farmer. The commons were divided and privatised, and collective land use was made away with. In general, private property rights were strengthened and individualistic use of land was stimulated. The new law was less strict as to how many plots each landowner retained, up to three were allowed, but that included the private plot of forest or old pastures. Laga skifte normally concerned arable as well as meadows and forest lands and all fencing between previous meadows and arable fields were abolished. A landowner could get less arable land than before, but was in that case compensated with more meadows suitable to clear into arable fields. All land was graded and more land of lower quality could be exchanged for less land of better quality and vice versa. Except for the plains of Scania, Öland and parts of Skaraborg County Laga skifte became the main form of radical enclosure in Sweden. In the wooded and northern parts of Scania and in much of southern Sweden enclosures peaked in the 1830s and the 1840s. The further north we go, the later the enclosures were carried out. In East central Sweden, the 1850s was the most intensive period.Footnote7

In many regions, radical enclosures transformed the countryside: tightly packed villages were scattered into individual farms surrounded by their consolidated farmland. The radical enclosures – Enskifte and Laga skifte alike – implied that some villagers had to move out from the village centre and, particularly following Enskifte, that many villages disappeared as settlement units. The privatisation of practically all collective property and the individualisation of plots also implied that the village ceased to exist as cooperative units with the right and imperative to make decisions valid for the villagers in common.Footnote8

The law gave each landowner in the village the right to demand enclosure and force it up on the other villagers, whether they liked it or not. This made it comparably easier for eager landowners to enclose land in Sweden than in, for example, England, where owners representing the qualified majority of the land in the village had to favour enclosure for the redistribution to come about.Footnote9 Despite this radical nature of the enclosure law (implying that every single landowner had a veto against any majority not wanting to enclose), the enclosure process took a long time and 80 years later, many villages were still not enclosed.Footnote10

On the one hand, it has been widely argued that enclosures were positive for agricultural productivity as it eased individual investment decisions. It is believed that enclosures stimulated the clearance of new land and allowed a more rational land use with specialisation in certain crops, the introduction of convertible husbandry and new more intensive crop rotations with little or no fallow. On the other hand, another strand of literature has argued that the enclosure movement mainly caused a redistribution of land and incomes, leading to increasing inequality in land ownership and raised rents.Footnote11 Some researchers have argued that enclosures destroyed functioning road networks and, by dispersing settlements, made it harder to introduce communal roads, water, sewage and electricity facilities at a later stage.Footnote12

The problem investigated in our article is based upon the description above. If, in Sweden, radical enclosure was fairly easy to accomplish, landowners were enabled more strict individual control over their properties, a more rational use of land and increased land productivity, or enabled actors to redistribute land in their favour, then why did the process drag on for so long? This problem has been widely discussed in the literature on enclosures, but to our knowledge, few have actually tried to estimate the determinants of the timing of enclosures.Footnote13 The purpose of this paper is thus to investigate the timing of enclosures in the county of Västmanland and pinpoint factors which accelerated or decelerated this process, but also to determine what factors made some farmers eager to enclose while others did not strive for it, thus why some villages were enclosed early and some late (or never).

This article uses a newly constructed database of the timing of enclosure of all villages defined as agricultural units in Västmanland, as well as a subsample of 100 villages, with at least two owners, where ownership structure is followed over time. Using a Cox Proportional Hazards model, we find that highly scattered land ownership, issues of coordination and market growth all played a part in the timing of enclosures in Sweden. The conclusion is that – as would follow from rational behaviour – villages were more likely to enclose when the benefits of enclosures were perceived to exceed the costs.

2. Previous research on the timing of enclosures

A number of factors might have acted as stimuli for initiation of enclosures. Fundamental in the discussion about the incentives for and timing of enclosures has been a need for clearer property rights, the question of the inefficiencies of the open-field system and the urge for privatisation of the commons.Footnote14 An important issue has been how the distribution of land ownership affected the timing of enclosures. In the English case, the chronology of enclosures and the variations in the share of enclosed land between nearby regions have been attributed to differences in ownership. In parishes where one landowner owned most of the land the enclosures were carried out earlier, while in areas with many landowners the process became more complicated and slower. When the economic benefits became apparent, the share of enclosed land increased also in parishes with more mixed ownership.Footnote15 For Spain, Beltrán Tapia has raised the question of the timing of the dissolution of communal regimes, and analyses why commons persisted longer in some areas in the country than in others. He emphasises that there was an interaction between social and environmental factors at force.Footnote16 Beltrán Tapia means that regional environmental factors are important for understanding the different timing of the dissolutions of the commons. For example, in mountain areas, the commons survived longer because they were important in the agriculture that combined farming, animal husbandry and forestry. On the other hand, the commons were dissolved to a greater degree in provinces with more unequal land distributionFootnote17 after legislative changes in the 1860s, after which the landowning elite opted for privatisation in order to secure control over the resources within the commons.

In the Low Countries, communal land existed only in the eastern and southern regions during the eighteenth and nineteenth Century. For the eastern parts of the Netherlands, Luiten van Zanden has studied commons and factors that determined the speed and the outcome of their dissolution process. He stresses the importance of governmental legislation making it easier for individual landowners to successfully demand enclosure, but also points towards economic motives with large landowners wanting to transform their shares in the commons into marketable real estates.Footnote18 In Belgium too, institutional factors promoted the enclosure process, for example, the 1847 law for reclamation of uncultivated land, after which villages sold their common land.Footnote19

In Sweden, the radical enclosure process in the villages was earlier and faster in the southern and western parts of the country.Footnote20 An earlier view of the lag of enclosures in the eastern part related it to the large proportion of landowning by the nobility. The hypothesis was that landowners with large estates could reform their farming themselves without making use of any enclosure legislation. According to an old historical research tradition, Swedish freeholders were hesitant or opposed to enclosures. This image has been strongly questioned by later scholars, and freeholders have instead been assumed, and been shown, to have had a role as supporters of, and initiators of the enclosure reforms.Footnote21

While the Storskifte normally left the settlement structure unchanged, the number of strips for each owner was, however, sharply reduced, and if villages were small, as they normally were in eastern Sweden, this should have reduced the need for a radical enclosure (Enskifte or Laga skifte).Footnote22

The size of the villages has been pointed out as a driving force for enclosure, as well as complex or fragmented land distribution within the open-field system. A farmer with arable land in many different places had higher production costs compared to a farmer with concentrated fields, as the moving of labour, towing animals and equipment resulted in higher costs.Footnote23 Thus the higher the number of plots per farmer, the more likely it would be expected that some landowner in the village demanded radical enclosure.

Agricultural-technical-related factors have also been put forward as a cause of early or belated enclosure movement in different regions. For example, the need to switch to new crop rotations with fodder plants has been proposed as one of the most important motives, as it has been believed that changes in land-use arrangements presupposed enclosures. For England, it has been argued that the need for introduction of convertible husbandry, modern crop rotations and rational cultivation methods were driving forces to enclose. Parliamentary enclosures have been seen as an important element of the increase in agricultural productivity in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century. An opposing view is that the great increase in productivity took place during other periods than when the enclosures were most extensive, that the transformation of the system of cultivation did not require enclosure and that enclosures mostly resulted in redistribution of incomes.Footnote24

Another theme considered in the discussion of the chronology has been the emergence of markets and the importance of price changes. The costs of enclosure are an issue that has been discussed as important for the process. Some scholars, notably Utterström (Citation1957) and Fridlizius (Citation1979) have emphasised the importance of increasing prices of rural products as a motivation to enclose land. If an enclosure could be expected to contribute to increased production and to higher profit, it was an incentive to enclose. In addition, in economically good times, the farmers could more easily afford to finance enclosures, which likely made them more positive to the reform.Footnote25

Dahlman (Citation1980) argues that, from a property rights and transaction costs perspective, the open-field system will remain in a village as long as the costs of the system were lower than its benefits. He argues that the costs of the open-field system mainly consisted of the scattering of land, collective decision making, communal ownership of scarce resources and unexploited advantages in specialisation. These were, on the other hand, offset by benefits yielded from collective fencing and herding when it came to animal husbandry. Enclosure would, according to Dahlman, then only be implemented if the anticipated income from enclosure would outweigh the lump-sum costs of the reform. The former would depend upon market growth and technological progress, yielding increasing returns from specialisation in cash crops. The latter consists of several components: fixed costs that could be somewhat predictable such as fencing, clearing of land, construction of new buildings, but also unpredictable costs consisting of compensation to individuals that had perceived or real losses from the reform. This has a lot to do with coordination within the village. If there was no consensus for enclosure and one farmer in a village appealed against the new distribution of land, costs could increase unpredictably.Footnote26

The enclosures in Sweden were financed by the landowners in the villages. The process was rather expensive, but it is difficult to provide details of exactly how much money was involved either in total or per acre. The costs fell under two main headings, payments to the commissioned land surveyors and relocation of buildings. Still more resources were spent in the actual physical work of enclosure: the making of new fences, new ditches, new roads and the cultivation of previously un-ploughed meadows and pastures. Some small grants from the government existed, but could be withdrawn if conflicts led to court procedures.Footnote27

Studies of enclosures in the southernmost part of Sweden, Scania, have shown that villages on the plains were enclosed earlier than villages in forested and mixed areas.Footnote28 This has been explained by the relative simplicity to redistribute topographically even land, by the particularly good cultivation conditions on the plains and by the early and thorough commercialisation of agriculture on the southern plains. For Scania, studies by Olsson and Svensson (Citation2010), Bohman (Citation2010) and Nyström (Citation2019) have shown that radical enclosures in the early 1800s strongly contributed to productivity growth and extensive land reclamation. But both the process as such and the mechanism whereby enclosures contributed to productivity growth are partly unclear: was it because enclosure allowed for deeper intensification of land use? The impression from Dahl (Citation1941) and Dahl (Citation1942) is that much of the growth of production stemmed from the post-enclosure permanent clearance of pastures which had only occasionally been used for cultivation of oats. Lägnert (Citation1955) seems to indicate a clear correspondence between early enclosures in the south and the introduction of new, intensive crop rotations with very little fallow. For the County of Halland enclosures have been claimed by Wiking-Faria (Citation2009) to have been less important for the agricultural development.Footnote29 For the county of Västergötland, Nyström and Hallberg (Citation2018) have examined the price differential between enclosed and unenclosed land in neighbouring areas and their results point towards no distinct productivity differences, until around the 1860s when new crop rotations were introduced on enclosed land.

To sum up earlier research points towards a diversity of factors determining the likelihood of villages being enclosed and thus the timing of radical enclosures, namely the size of villages; the distribution of landownership, the number of plots per landowner/peasant; the need for reformed land use, price trends and economic cycles; the type of rural area (plains, forested land, etc.) involved; the degree to which farming in a particular area was commercially directed; the extent to which earlier enclosures (Storskifte) had already opened for a more rational land use and finally the rational farmer’s calculus of costs and benefits of enclosures.

3. Data and methodology

In order to study what factors were important for the amount of time it took for villages to apply for enclosure, we have collected a database containing all villages and taxed agricultural units in the county of Västmanland during the nineteenth century, using data from land survey maps. The database provides a descriptive overview of the enclosure process in the county.

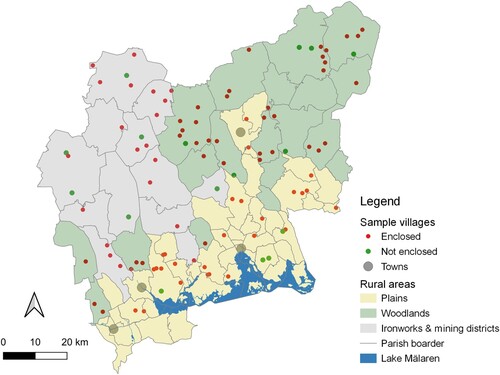

The county of Västmanland is located in what is usually labelled East Central Sweden, with its southeastern border ca 100 km west of Stockholm (see ). The county has a varied rural landscape and relatively large topographical differences. Around 1900, only 23% of the land area was arable, while 58% was covered by forest.Footnote30 The southern part of the county consists of fertile plains next to the Lake Mälaren. In the northern part, the landscape is dominated by woodlands, with larger arable stretches only along the five rivers running from north towards the Lake Mälaren. The northwestern part is an area historically dominated by mining and iron works. This area is referred to as Bergslagen. In this study, we use a division of the county into three areas according to these topographical structures: plains, woodland areas and mining/iron works areas.Footnote31

Most of the historic settlements were organised in relatively small hamlets. On average, the mantalFootnote32 (tax unit) was only 1.35 per village with an average of four to five landowners and farmsteads. Compared to much of Southern and Western Sweden, the villages were thus very small, but there were exceptions, mostly in the mining areas and in the southwest. The areas close to Lake Mälaren were dominated by large properties and mansions owned by the nobility, and large estates were common in the mining areas as well. These were owned by iron works proprietors and companies. Both the estates of the nobility and the iron works-proprietors generally owned large areas of land, which could be distributed between the central estate (demesne) and leased out farms in several villages.

The county thus includes a varied economic structure and should thus be representative for the larger region of central Sweden. It is distinctly different, however, from the plains with large villages in Scania, Skaraborg and Öland.

3.1. The enclosure process in Västmanland county

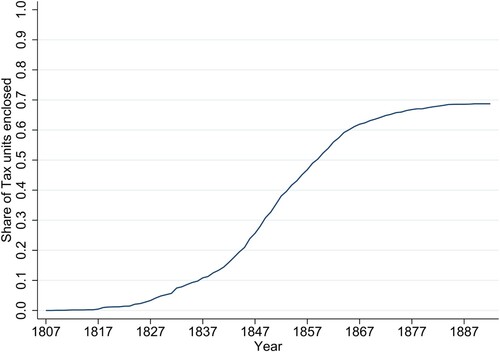

The enclosure process in Västmanland county took about 90 years and was not fully completed until the 1920s. We have studied the period 1807–1892, when around 1220 radical enclosures took place. Out of these only 47 were enclosures according to the edict of Enskifte (1807–1827), many of them incomplete. The rest were Laga skifte enclosures from 1827 onwards. Of the county’s total tax units (mantal), 68.7% were radically enclosed in the period between 1807 and 1892, 66.5% of the mantal had been enclosed according to the Laga skifte legislation, i.e. after 1827. depicts the evolution of radical enclosures in the studied county.

Figure 2. Share of enclosed tax units (mantal) in Västmanland County 1807–1892. Source: Rikets allmänna kartverk (kartor och beskrivningar) Beskrivningar till konceptkartorna öfver Västmanlands län (1916).

The frequency of enclosures varied over the years. After the very few events of Enskifte, the process had three phases: a relatively slow start phase after 1827, an intensive phase during the 1840s, 1850s and early 1860s, and a slowdown phase from the late 1860s. The highest concentration of enclosures was reached during the 1850s. After 30 years from the starting point of the Laga skifte edict, no more than 50% of the radical enclosures in the county had yet occurred. The process was drawn out in terms of the county as a whole, but the analysis of all the enclosure acts, show that this was also true within parishes. On average, the time period between the first and last radical enclosure in individual parishes was 42 years. The long-time span means that enclosed villages could persist side by side with unenclosed ones for decades.Footnote33

3.2. Variable and sample selection

As noted in Section 2, a number of different factors have been argued to be important for the timing of enclosures. We take an eclectic approach to variable selection and try to include as many relevant factors as possible. These factors and how we measure them have been summarised in below.

Table 1. Important factors for enclosure.

As several variables, such as the number of owners, concentration of ownership and the number of farmers to landowners in , vary over time, it is clearly not appropriate to only rely on land surveys in the early twentieth century to investigate our question. Because of this, a stratified random sample of 100 agricultural units has been drawn from the database. The sample from each stratum has been weighted by the geographical size of each economic/rural area in order to avoid any geographical bias in the sampling. Time-varying data (number of holdings per village unit, number of landowners, etc.) for this sample have been collected from poll tax assessment rolls (mantalslängder) in five-year intervals starting in 1807 and ending in the year that they were enclosed in order to solve this issue.Footnote34 As enclosure was only needed and possible in villages with more than one owner, we have limited the sample by only sampling from villages with two owners or more in 1807. In the case that the ownership in a sampled village was totally concentrated to one owner during the study, the village has been censored.

As can be seen in below, the sample drawn from the population is relatively evenly spread across the region and covers most parishes. The distribution of enclosed and unenclosed villages was also relatively evenly spread, and there seems to be no clear geographical pattern in the data.

Figure 3. Map over Västmanland with sample and rural areas. Source: Enclosure acts, Lantmäteriet (www.historiskakartor/lantmateriet.se). For rural areas, see note 27.

The database enables us to describe some general characteristics concerning enclosed and unenclosed villages in early twentieth century Västmanland. In below, one can clearly see that the variation among agricultural units was large. The smallest agricultural unit consisted of just 2.4 hectares of land whereas the largest consisted of 9266 hectares. Enclosed villages were larger on average, both concerning tax units and acreage. They also had a larger share of freeholder’s land (skattejord) than manorial land (frälsejord). The number of holdings was also greater among enclosed villages. Finally, the enclosed villages had more arable land relative to other types of land on average. This implies that the villages that were enclosed were either more specialised in grain production (at the time of enclosure) or reclaimed land to a larger extent than unenclosed villages after enclosure.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of taxed agricultural units in Västmanland 1906–1911.

As already noted, relatively speaking, there was a rather low proportion of villages and units in the county that were enclosed in the early 1900s, when the Häradsekonomiska kartan was constructed. Circa 43% of the units neither went through Enskifte or Laga skifte. The reason for the relatively low proportion of enclosed units in the county has not been studied here, but one possible reason can be that a great part of the non-enclosed units was single-farm units. Out of the 1828 taxed agricultural units for which Häradsekonomiska kartan reports the number of taxed farm units, 708 had just one taxed farm unit in the beginning of the twentieth century.

As we have sampled villages with at least two owners, there is an expected difference between the means in the total population of taxed agricultural units and the sample. The villages in the sample were larger on average, both in terms hectares and the number of tax units, than the total population. This, however, is no problem as our population of interest is villages where enclosure was possible.

One important variable (see ) is the number of field plots per owner. Many plots in the open fields led to larger time losses in terms of transport of material and tools between them. Plots might also have tended to become impractically narrow if there were many of them. With only a few plots per field, the individual farmer might have had a chance to act rather independently when it came to choosing crops and when timings of operations were concerned, even if the village was not radically enclosed. With many narrow stripes in the fields, this was hardly possible. We know the number of plots per owner only when the village had gone through Storskifte before it was radically enclosed. As 74% of the villages in the sample of 100 had gone through Storskifte and we let these 74 villages form a subsample in order to test the impact of the number of plots (or strips) per owner, on the timing of radical enclosure.

4. Who applied for enclosure?

Individuals had great influence on when the enclosures took place since it was enough with a single landowner in a village to apply for enclosure for it to be implemented. To examine if there were any significant relations between applicants and the timing of enclosure, we have studied who applied for enclosure for every Enskifte and Laga skifte enclosure from 1807 to 1890 in the county. Of course, for each applicant there were several individual characteristics and conditions that remain completely unknown, but what can be done is a rough categorisation of applicants into different groups. We have categorised them into four groups according to their socio-economic positions: Large estate owners, freeholders, officials and merchants and finally representatives of institutions (the Crown, the Church) ().

Table 3. Enclosure applicants by social group.

In terms of the entire period 1807–1890, the majority of applicants for enclosure were freeholders. Overall, they accounted for 64% of the applications. Large estate owners accounted for 15%, 5% of the applications were made by officials and merchants, while 3% were made by representatives of institutions. Thirteen per cent of the applications were jointly made by all landowners in the village, which almost exclusively involved freeholders. The dominance of freeholders among applicants reflects that freeholders owned most of the agricultural land in the county. There were a large number of villages in the county where freeholders were the only landowners and consequently the only ones who could apply for enclosure. There is a tendency that large estate owners were more active to apply for enclosure during the early period. As have been shown in above, the majority of the enclosures in Västmanland county were applied for before 1870. During this period, most applications were not made by all the landowners together. Consequently, we expect that issues of coordination might be of significance for the study.

It is also clear that an unproportionally large share of enclosures, applied for before the 1840s, was applied for by large estate owners (29%). If we speculate that all owners who applied altogether were freeholders, then 77% of the applications stemmed from freeholders in the entire period, 56% in 1807–1840, 78% in 1841–1864 and 87% in 1865–1890. The dominance of freeholders amongst applicants thus grew over time.

5. Empirical strategy

The nature of our question lends itself quite nicely to a survival analysis approach. We use a Cox Proportional Hazards modelFootnote35 to investigate what factors increased or decreased the probability for enclosure. This model has been most commonly used in medical research, but can be used in most time-until-event studies.

Formally,Footnote36 the Cox model can be specified as:

(1)

(1) where the hazard at time t is the function of an unspecified baseline hazard function h0, Xi is a vector of covariates and βi is a column vector of coefficients. Xi can be either fixed over time or time varying. A key assumption of the Cox Proportional Hazards model is that hazard ratios are constant over time, i.e. that they are proportional, which enable the model to specify hazard rates without estimating the baseline hazard for the model.

If hazard ratios are not constant over time, i.e. the coefficient of some covariate X is not constant over time; one solution is to use an extended Cox model.Footnote37 This implies interacting the specific time-dependent covariate with some function of time g(t) so that

(2)

(2) The functional form of g(t) needs to be modelled so that it describes how the hazard ratio of the time-dependent variable changes over time. There are several ways to model time, such as a linear function g(t) = t or model it as the natural logarithm of t, i.e. g(t) = ln(t). Another possibility is to use a heavy sided function to split the dataset in two or more parts where the hazards are proportional.Footnote38

To test if hazards are proportional, the standard method is to use the Therneau and Grambsch nonproportionality test. The test statistic can be interpreted as a measure of the correlation between the covariate-specific Shoenfeld residual and event times, and a significant result indicates that the proportional hazards assumption has been violated. However, the test is also indicative of other model failures which may yield false-positive results, such as omitted variables or functional form misspecification.Footnote39

6. Results and discussion

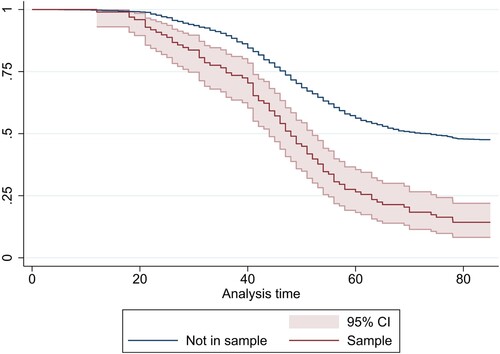

As we noted in Section 3.2 above, the sample differs from the total population of villages and agricultural units in Västmanland due to the fact that our population of interest is the villages that were at risk of enclosure. The difference in the rate of enclosure can be clearly seen in below where the Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of the sample and the total population of taxed agricultural units are compared. This difference is most likely due to a large number of taxed solitary farms or villages with a single owner which consequently had no need to enclose.

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of enclosure in Västmanland 1807–1892. Source: Enclosure acts in LMA (www.historiskakartor/lantmateriet.se), Rikets allmänna kartverk, Beskrivningar till konceptkartorna öfver Västmanlands län (1916).

The hazard function of enclosure followed a quadratic pattern and was greatest in the late 1840s and early 1850s, after which it decreased rapidly.

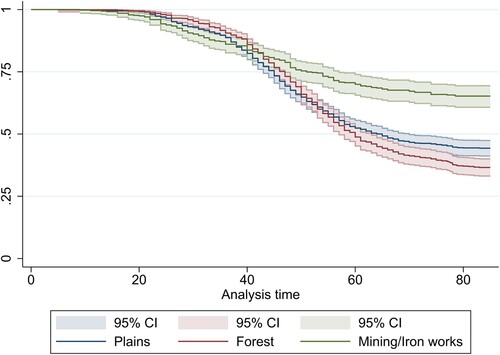

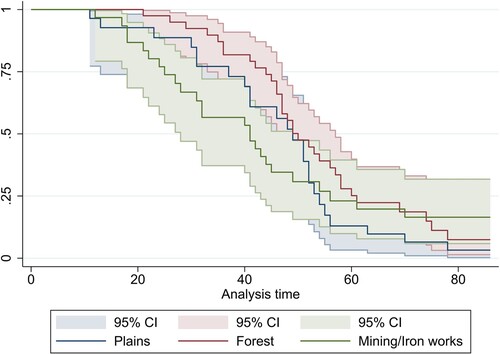

The economic orientation of different areas seems to have mattered quite significantly for the rate of enclosure. The process was somewhat quicker in the mining and iron-working areas during the first years. But in the 1840s and 1850s, as can be seen in below, there was a main acceleration of enclosures in plains and forest regions whereas the mining and iron-working areas enclosed to a lesser degree. This is somewhat surprising, as one might speculate that iron works owners would have tried to have forest land privatised in order to secure access to charcoal. Also, the enclosure of forest regions accelerated somewhat compared to on the plains, which might possibly be due to a greater potential for reclamation of land which has been argued to have been a factor in enclosure. This too is at odds with the experiences from, for example, Scania, where the villages on the plains tended to get enclosed earlier than villages in forested areas.

Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of enclosure in Västmanland by rural area 1807–1892. Source: Enclosure acts (www.historiskakartor/lantmateriet.se), Rikets allmänna kartverk (kartor och beskrivningar) Beskrivningar till konceptkartorna öfver Västmanlands län (1916).

One possible explanation for the lower rate of enclosure in the mining and iron-working areas is that the Laga skifte act had a paragraph stipulating that, in Bergslags districts, previously enclosure of forests with the Storskifte legislation could not be altered with the Laga skifte legislation without a unanimous decision by all owners in the village.Footnote40 This might have reduced the ability of iron works owners to privatise forests. Another could simply be that grain production was less important to the economy of these districts, thereby lowering the incentives for paying the costs associated with enclosure. An even simpler explanation could be that there were a large number of small agricultural units with a single owner in these regions, which would make enclosure pointless. If this was the case, once the larger villages in the regions were enclosed, the rate of enclosure would decrease rapidly.Footnote41

This could also explain another area where the sample differs from the population, that is in the rural area variable. As can be seen in below, the difference in the rates of enclosure between different rural areas is not statistically significant in the sample. This is a clear difference compared to the picture in the total population. We can thus expect the variables for rural areas to be insignificant when running the Cox regression.

Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of enclosure in our sample by rural area 1827–1892. Source: Enclosure acts (www.historiskakartor/lantmateriet.se), Rikets allmänna kartverk (kartor och beskrivningar) Beskrivningar till konceptkartorna öfver Västmanlands län (1916).

In order to test what factors that increased or decreased the risk of enclosure, we estimate several Cox proportional hazards models. In addition to our baseline model described above, we test a number of models to check the robustness of our results as there are several issues that might cause problems for the model. The first is multicollinearity. As can be seen in below, there is a high correlation between the HHI-index, the number of owners and the size of the village in Tax units.

Table 4. Pairwise correlations of variables.

As multicollinearity might inflate the standard error of the coefficients, these should be interpreted with care, and, although it does not solve the issue, we also show the effect of dropping each of the correlated variables from the model.

Second, we check for functional form misspecification and add polynomials where there are non-linear relationships. This is needed for the GDP/capita growth variable that exhibits a non-linear relationship in the model. Third, as this variable also displays non-proportional hazards, this is controlled for by a time-interaction.

The results from the models are presented in and below. In total, 12 models are tested, where the hazard ratios are presented for each model. Further robustness checks are also presented in .

Table 5. Cox proportional hazards model with full sample.

Table 6. Cox proportional hazards model with subsample.

Table 7. Cox proportional hazards model, robustness tests.

Although the sample size is rather small and the results need to be interpreted with some care, the results from the regressions show several interesting patterns.

Firstly, it is quite clear that the number of farmers in relation to the number of landowners (frequency of leaseholds) increased the probability of enclosure. A doubling of the number of farmers in relation to the number of owners increases the probability for enclosing at any point of time with approximately 400%–450%. The wish to concentrate several holdings to one location, and thereby increase direct control and the possibility to reorganise the farming of the property, thus seems to have been an important factor that raised the probability of enclosure. The Laga skifte act specifically promoted that owners of more than one holding could concentrate their land ownership to one location, if possible,Footnote42 and some owners explicitly stated that this was the goal when they applied for enclosure. When, for example, C. F. Gyllenhaal applied for enclosure in 1850 he wrote to the land surveyor asking for the properties to be reorganised:

… so that my owned parts there become lawfully separated from the other part-owners in these enclosures and, as far as possible, be placed in junction with the previously mentioned bordering properties, and finally, in all these my properties to execute the levelling and divisions etc. that could be found necessary for ditching and the organization of a prudent farming and a good management of the main farm, with its subordinate farms and crofts.Footnote43

In all specified models that include land ownership concentration, it had a significant negative effect on the rate of enclosure. An increase in the HHI-index of 100 points decreased the rate of enclosure by about 4.5%. Villages where the concentration of ownership was high and the coordination of land use thus should have been easier, also had a lower risk of enclosure, i.e. they tended to enclose later.

Due to the issue of multicollinearity, it is hard to disentangle the possible effects of the size of the village and the number of owners as it might inflate standard errors. However, if the size of the village in tax units did not influence the timing of enclosure in a statistically significant way, this result might indicate that the adoption of labour-saving technology or travel distances was not a significant driver of the enclosures in Västmanland. An explanation is simply that other than improved ploughs and harrows, not much new technology was yet available, and clearly none so far that requested more consolidated and broad fields. Field machinery like mowers and harvesters were hardly introduced before the 1870s, and not particularly common before the turn of the century.Footnote44

The number of owners might also have had a weak statistically significant negative effect on the hazard of enclosure. In that case, the greater the numbers of owners, the lower the probability of enclosure. An increase in the number of owners by one decreased the hazard of enclosure by about 7%. The absolute majority of the enclosures before 1870 were not applied unanimously by all farmers in the villages and conflict among the farmers could thus potentially cause an asymmetric increase in the costs of the enclosure. This might indicate that issues of coordination of enclosure, and consequently, costs were of importance to the timing of the enclosure process.

Real GDP per capita growth also had a statistically significant impact on the hazard of enclosure. However, this effect is non-linear and, furthermore, the effect decreased linearly over time. This implies that in 1807, an increase in the GDP per capita growth by 1 percentage point annually lead to an increase in the risk for enclosure by 350%. In 1808, a similar growth leads to an increased risk for enclosure by 348%, etc. We thus find that market growth was of importance to the enclosure process, which, for example, Utterström (Citation1957) has argued for.

In below, we use a subsample to estimate the effect of the average number of plots per owner on the risk of enclosure. As one of the main goals of the radical enclosure was to reduce the number of plots and concentrate them to one location, villages with many plots per owner should have had incentives to enclose earlier.

The table gives the result for the subsample of villages that had gone through Storskifte. Here for obvious reasons, we do not test the impact of Storskifte upon the risk of radical enclosures, as all villages in the subsample had gone through Storskifte. The variables that showed significant coefficients in did so also for the subsample. There was a little increased probability for enclosure with a raised relation between holdings and owners, and also for GDP/capita growth. Of more interest are the results of the impact of varying number of arable plots or strips per landowner. This variable is not significant in itself, but if it is interacted with the type of rural area variable, it is shown that in the plains, the risk for enclosures increases with 14.3% if the number of plots per owner increases by 1. This is expected: the more fragmented fields owners had, the more likely it ought to have been that they (or at least one of them) opted for enclosure. This, however, is not true for forested areas or the mining areas where the summed effect of the interaction coefficients is close to zero.

6.1 Robustness checks

In order to check the robustness of our results, we have run a number of robustness tests. We have used dfbeta-measures of influence and likelihood displacement values to make sure that no single village is driving the results. In below, we also test if including distance to towns or yield ratios for different crops as control variables change the results to any large degree. One concern with the GDP per capita growth variable might be that there was a non-causal temporal correlation between increasing growth rates and the increasing number of enclosures up until the late 1870s, when most villages were enclosed and growth rates declined due to the recession of the late 1870s. Consequently, we test if our results are robust to an alternative specification of the growth variable in the form of an indicator variable where 1 indicates expansion in GDP per capita growth and 0 indicates contraction. We also test if the ownership concentration variable is robust to an alternative specification using an indicator variable that is equal to 1 when more than 50% of a village is owned by a single owner and equal to 0 otherwise.

We have used data from Hammar (Citation1860) which includes the distance of the parish church to the closest town for all parishes in Sweden. The relation is weakly significant and shows that if the distance to the nearest town increases with 10 km, then the risk of enclosure at any time decreases by 11%. Thus, it would seem that the higher the possibility to market farm output (grain), the higher the propensity to demand enclosure. But, again, the significance is a bit weak and the proxy for distance to town we use is not incredibly sophisticated. Therefore, the result should be regarded as somewhat hypothetical. Good harvests in the previous year could theoretically increase the amount of grain that can be put to the market. If harvests were poor in the previous year, most of the harvest had to be consumed by the household. Good harvests would on the other hand enable larger cash incomes. We use one-year lagged yield ratios for the three most important crops in Västmanland: Rye, Oats and Potatoes. Including yield ratios, however, does not affect the overall results to any large degree. Using alternative variables for the economic growth and ownership concentration do not change our results in any significant way. There was a significantly larger risk for villages to enclose during periods of economic expansion than during periods of contraction, although the estimate is imprecise, which might be due to the fact that it does not take the size of the economic contraction/expansion into account. Villages where the majority of the land was owned by a single owner also had a significantly lower risk of enclosure, which is in line with our overall results.

7. Conclusions

This paper addresses factors that drove the timing of enclosures in Västmanland in the nineteenth century. Why did some villages enclose earlier than others and why did the process drag on for so long? Our results indicate that the enclosure process in Västmanland county was driven to a large extent by an economic rationale where market growth, coordination problems within villages and owners seeking to increase control over their property all influenced the enclosure process.

According to our results, the probability of enclosure was significantly higher during periods of high real GDP per capita growth, possibly due to a greater ability to bear the costs or access capital during these periods, or reflecting market growth and a higher optimism among farmers to receive higher returns on their crops. Our results are thus in line with those of Fridlizius (Citation1979), Utterström (Citation1957) and Dahlman (Citation1980) who argue that market growth and the costs of enclosure are important for understanding the process.

Village size in itself does not seem to have been a factor in the process and possibly the small villages in Västmanland county had little potential in optimising field use through economies of scale and adopting new technologies. Nyström and Hallberg (Citation2018) argue that the difference in price per tax unit and amount of seed per tax unit between enclosed and unenclosed land was negligible up until the 1850s in Western Sweden. This most likely meant that unenclosed and enclosed farm units were both able to clear new land for sowing at about the same pace. It also seems possible for both enclosed and unenclosed villages to use the same production technology, at least until the very end of the studied period. If this was the case in Västmanland county as well, it is reasonable that the size of the village did not matter for the timing of enclosures. On the other hand, the scattering of land could still be costly. According to our results, the higher the number of arable plots per owner, the higher was the propensity to enclose. This was at least the case for villages on the plains, which arguably were more dependent on grain production and where the scattering of land consequently was costlier, whereas the number of plots did not have a significant effect in the forest and iron-working districts.

Coordination problems within the villages also seem to have been important for the timing of enclosure. Enclosures were applied for later in villages where the ownership concentration was high, and where decision making within the village concerning grazing, planting and harvest was controlled by a few large landowners. Although our results concerning the number of owners should be interpreted with caution due to possible multicollinearity, they could indicate that the larger the number of owners, the lower the probability of enclosure was. This might be due to coordination issues which potentially lead to higher costs and uncertainty.

Additionally, one of the answers to why the enclosure process dragged on for so long may be various views of the positive effects of enclosure among different landowner groups. As can be seen in , the gentry applied early for enclosure, and obviously, there were those within that group who early saw the benefits of the reform. By enclosing, landowners increased the control of their property. We have concluded that villages in which landowners had more than one holding were more eager to enclose, as, in this way, they were able to get their holdings directly connected to each other. It seems highly probable that in the long run this eased the formation of larger farming units. Partly similar patterns have been shown for Spain and the Netherlands, where large landowners acted to secure their control over common resources (Beltrán Tapia, Citation2015; Van Zanden, Citation1999).

But early applicants in Västmanland also included many freeholders which was the largest landowner group in the county. This was a heterogeneous group with major economic and social differences that, apparently, not until very late appreciated the rationality in enclosure. As our results show that in the enclosure process farmers were sensitive to market signals, it is possible that, in villages that either were not enclosed, or were enclosed late, the farmers either could not afford it or did not see it as that economically beneficial. This could partly explain the lengthy process.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this text was presented by Marja Erikson at the session ‘Enclosure, agriculture and landscape change: Regional studies’ at the European Rural History Organization International conference in Paris 2019. Thanks for valuable comments are due to participants at the session, in particular the discussant, Dr Lars Nyström, and to three anonymous referees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For the development in Scania, see Dahl (Citation1942), pp. 179–180; for southern Dalarna Isacson (Citation1979), p. 64; for Bohuslän, Widgren (Citation1997), p. 9; for Värmland Granér (Citation2002), pp. 256–285. Cf. Hoppe (Citation1997), p. 254.

2 An overview of the regional spread of storskifte and a short description of what was intended and achieved, is found in Helmfrid (Citation1961). On the background, scf. Gadd (Citation1983), pp. 218–223. On the effects of the storskifte, see in general Gadd (Citation2000), pp. 273–282, more specifically and detailed on eastern Sweden. Olai (Citation1983). Cf. Olai (Citation1987). In many cases, the storskifte concerned only arable land. Quite often, the meadows and the outfields (the forest) of each village were redistributed in a separate act of storskifte (Lantmäteriet Västmanlands län). The latter implied that the common of the village was divided so each owner got one privately controlled part. Cf. Olai (Citation1987) and Hallberg (Citation2013), pp. 13–14. In Västerbotten (the then northernmost county) the Storskifte seem to have been more radical, with dispersion of villages and colonisation Utterström (Citation1957:I), p. 529.

3 On the intensity, effects and spread of Storskifte, see Dahl (Citation1941); Dahl (Citation1942), pp. 180–181, 184–185; Olsson (Citation2005), pp. 109–113; Nyström (Citation2019), pp. 172, 175–179. Cf. Gadd (Citation2000), pp. 278–279.

4 Dahl (Citation1942), pp. 186–187; Helmfrid (Citation1961), p. 14; Nyström (Citation2019), p. 172.

5 Utterström (Citation1957: I), pp. 547–550; Gadd (Citation2000), p. 291. As Gadd notes Enskifte in Skaraborg often did not divide land at smallest ownership level and in many cases these villages were re-enclosed following the statue of Laga skifte.

6 Lantmäteriet, Västmanlands län.

7 Helmfrid (Citation1961); Utterström (Citation1957: I), pp. 550–553; Gadd (Citation2000), pp. 292–294, 299–302; BiSOS H 1905, supplement.

8 The fierce criticist of enclosures, Frodin (Citation1945), pp. 301–302, complained about this fact, which however evolved slowly as villagers sometimes retained maintenance duties of common roads, etc. The view of the demise of the importance of the village has been disputed. Cf. Pettersson (Citation2003), p. 125; Ek (Citation1972), pp. 1–6.

9 Kongl. Maj:ts nådiga stadga om skiftesverket i riket av den 4 maj 1827. Cf. Overton (Citation1996), p. 160 and Turner (Citation1980), pp. 153–157.

10 BiSOS H 1905, supplement.

11 For Sweden the first view is represented, for example by Heckscher (Citation1945), pp. 201–202, 213–214; Heckscher (Citation1946), pp. 45–51; Utterström (Citation1957: I), pp. 571, 581–583; Gadd (Citation2000), pp. 274, 284–285; Gadd (Citation2011), pp. 149–154. For England the optimistic view is represented by, e.g. Overton (Citation1996), pp. 147–165. Overton, however, opens for the possibility that enclosures in many cases caused sharp redistributions in incomes. That latter view has been argued foremost by Allen (Citation1992). Contemporary supporters of radical enclosures viewed it as axiomatic that improved distribution of land and increased possibilities for individual entrepreneurship would result in raised productivity for the individual tiller and be favourable for society at large. Cf. Pettersson (Citation2003), p. 117.

12 Frodin (Citation1945), pp. 203–204.

13 Spain: Beltrán Tapia (Citation2015), England: Yelling (Citation1977), Sweden: Nyström and Hallberg (Citation2018). Utterström (Citation1957: I), pp. 537–546, 571, argues about the influence of access to credit, business cycles harvest volumes etc. These were market factors affecting each landowner and they likely determined during what periods enclosures were expanding and when not, but they do not help explaining why some farmers proposed enclosure at a certain point in the business cycle or harvest cycle, while others did not.

14 Pettersson (Citation1983), pp. 138–157.

15 Overton (Citation1996), p. 163.

16 Beltrán Tapia (Citation2015).

17 Beltrán Tapia (Citation2015) captures this using proxy measures: the number of landowners relative to the active agricultural population and the average farm size per owner in different provinces.

18 Van Zanden (Citation1999).

19 Brusse et al. (Citation2010).

20 Helmfrid (Citation1961); Gadd (Citation2000), pp. 299–302.

21 Storskifte: Olai (Citation1987), pp. 48, 73; Bäck (Citation1984); Wiking-Faria Citation2009; Gadd (Citation2000), pp. 281–282; Laga skifte: Pettersson (Citation1983); Bäck (Citation1992); Gadd (Citation2000), pp. 298–299.

22 This is proposed by Gadd (Citation2000), p. 301 as partly explaining the belated radical enclosures in eastern Sweden.

23 On the time use in the open field system, see Jupiter (Citation2020).

24 The traditional view, held by, e.g. Chambers and Mingay (Citation1966); Overton (Citation1996) stressed the importance for reformed land use and growth following upon Parliamentary enclosures in the late eighteenth century and the establishment of large capitalist farms, while Havinden (Citation1961); Kerridge (Citation1967); Jones (Citation1974) and later Allen (Citation1992) argued a revisionist view that convertible husbandry and agricultural growth largely predated this period of extensive enclosures.

25 Utterström (Citation1957: I), pp. 561–564.

26 Dahlman (Citation1980), pp. 178–181. In Sweden sometimes, landowners appealed the grading and redistribution of land, but they could not appeal the demand for laga skifte.

27 Hoppe (Citation1997), p. 267.

28 Dahl (Citation1941); Gadd (Citation2000), pp. 289–290.

29 Wiking Farias’ insistence that enclosures mattered little, fits in a general tendency amongst the large generation of agricultural historical writing in Sweden in the 1970s and 1980s to downplay the importance of enclosure, while still arguing that peasants were not reluctant to enclose. See Hallberg (Citation2013), p. 27.

30 Rikets allmänna kartverk (kartor och beskrivningar) Beskrivningar till konceptkartorna öfver Västmanlands län (1916).

31 To define parishes of plains in relation to parishes of woodlands we use a quota of forest-bearing land in relation to the total area, on parish-level (BiSoS 1872–1875). Parishes that had a share of forest-bearing land of more than 50% have been counted to the woodlands, the ones with less than 50% to the plains. A parish with at least one larger mine or iron works has been defined to belong to Bergslagen (mining/iron works area).

32 Mantal was a nationwide unit defining the size of farmsteads in terms of economic viability. It was also a unit for taxation. Originally one mantal signified a full-scale peasant farm with ability to procure for a household and pay all taxes, but over time, subdivision of farms had led to a situation where an average peasant farm held between 0.25 and 0.5 mantal in the Västmanland area. The size of villages could thus be measured in mantal, broadly representing the amount of agricultural land it comprised. See Thulin (Citation1890–1935).

33 Cf for the same phenomenon in Skaraborg county, Nyström and Hallberg (Citation2018).

34 ULA; Riksarkivet (www.sok.riksarkivet.se/digitala-forskarsalen).

35 Cox (Citation1972).

36 Therneau and Grambsch (Citation2000), p. 39.

37 Therneau and Grambsch (Citation2000), p. 147.

38 Kleinbaum and Klein (Citation2012), pp. 254–264.

39 Keele (Citation2010).

40 Kongl. Maj:ts nådiga stadga om skiftesverket i riket av den 4 maj 1827, p. 32.

41 This would also explain the difference between our long-term picture of enclosures in the mining and iron-working districts with those of Helmfrid (Citation1961) who characterised the iron-working regions in Västmanland as early enclosers. However, he only investigated villages with more than two farm register units whereas we have data on all taxed agricultural units which can also include small agricultural units.

42 Kongl. Maj:ts nådiga stadga om skiftesverket i riket av den 4 maj 1827, p. 36.

43 Lantmäterimyndigheten arkiv, Västmanlands län, Rytterne socken, 19-ryt-79. Authors translation, original text: ‘ … så att mina derstädes ägande delar blifva i laga ordning afskiljde från öfriga delägarnes i dessa skifteslag och, så vidt som möjligt, lagda i förening med de förstnämde intillgränsande egendomarnes ägovälden, och slutligen, att å alla dessa mina egendomar verkställa de nivelleringar och indelningar m.m. som kunna finnas behöflige för jordens afdikning och ordnandet af ett ändamålsenligt lantbruk, samt en planenlig skötsel af hufvudgården, med den under lydande hemman och lägenheter’.

44 Morell (Citation1992), pp. 105–108; Morell (Citation2001), pp. 274–284.

References

Unpublished sources

- Uppsala landsarkiv (ULA):

- Länsstyrelsen i Västmanlands län, Landskontoret

- Verifikationer EIc: 1820–1860.

- Häradsskrivaren i Kungsörs fögderi

- Mantalslängder FIaa: 1861–1892.

- Häradsskrivaren i Bergslags fögderi

- Mantalslängder FIaa: 1861–1892.

- Häradsskrivaren i Västerås fögderi

- Mantalslängder FIab, yngre serie: 1861–1892.

- Häradsskrivaren i Salbergs-Väsby fögderi

- Mantalslängder FIaa: 1861–1892.

Printed sources

- BiSOS H, Lantmäteri. 1905, supplement.

- BiSOS N, Jordbruk och boskapsskötsel 1869–1911.

- Hammar, Å. C. W. (1860). Socken-statistik öfver Sverige, efter C. af Forsells socken-statistik. Stockholm: Bonniers.

- Kongl Maj:ts Befallningshafvandes uti Westmanlands län till Kongl Maj:t i underdånighet afgifvna Embetsberättelse för åren 1829–1833. Stockholm.

- Kongl. Maj:ts nådiga stadga om skiftesverket i riket av den 4 maj 1827.

- Rikets allmänna kartverk (kartor och beskrivningar) Beskrivningar till konceptkartorna öfver Västmanlands län (1916).

Electronic sources

- Lantmäteriet. www.historiskakartor/lantmateriet.se

- Riksarkivet. www.sok.riksarkivet.se/digitala-forskarsalen

Literature

- Allen, R. (1992). Enclosure and the yeoman. Blackwell.

- Bäck, K. (1984). Bondeopposition och bondeinflytande under frihetstiden. Centralmakten och östgötaböndernas reaktioner i näringspolitiska frågor. LT.

- Bäck, K. (1992). Början till slutet. Laga skiftet och torpbebyggelsen i Östergötland 1827–1865. Noteria.

- Brusse, P., Schuurman, A., Van Molle, L., & Vanhaute, E. (2010). The low countries, 1750–2000. In V. Bavel, B. Van Cruyningen, & P.Thoen (Eds.), Social relations: Property and power (pp. 169–198). Brepols.

- Beltrán Tapia, F. J. (2015). Social and environmental filters to market incentives: The persistence of common land in nineteenth-century Spain. Journal of Agrarian Change, 15(2), 239–260. doi:10.1111/joac.12056

- Bohman, M. (2010). Bonden, bygden och bördigheten: produktionsmönster och utvecklingsvägar under jordbruksomvandlingen i Skåne ca 1700–1870 [Dissertation]. Lunds Universitet.

- Chambers, J. D., & Mingay, G. E. (1966). The agricultural revolution 1750–1880. B T Batesford.

- Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 34(2), 187–202.

- Dahl, S. (1941). Storskiftets och enskiftets genomförande i Skåne: Tabeller och kartor. Scandia, 14(1), 86–97. https://journals.lub.lu.se/index.php/scandia/article/view/566

- Dahl, S. (1942). Torna och Bara. Studier i Skånes bebyggelse-och näringsgeografi före 1860. Carl Bloms Boktryckeri.

- Dahlman, C. J. (1980). The open field system and beyond: A property rights analysis of an economic institution. Cambridge U.P.

- De Moor, T. (2009). Avoiding tragedies: A Flemish common and its commoners under the pressure of social and economic change during the eighteenth century 1. The Economic History Review, 62(1), 1–22.

- Ehn, W. (1991). Mötet mellan centralt och lokalt: studier i uppländska byordningar [Dissertation]. Uppsala University.

- Ek, S. B. (1972). Fiktioner om 1800-talets kulturomvandling. Rig. Kulturhistorisk tidskrift, 55(1), 1–6. https://journals.lub.lu.se/rig/article/view/8464

- Fridlizius, G. (1979). Population, enclosure and property rights. Economy and History, 22, 3–37. doi:10.1080/00708852.1979.10418960

- Frodin, J. (1945). Skiftesväsendet och dess samband med jordbrukets nuvarande kritiska läge. Ekonomisk tidskrift, 47(4), 295–308.

- Gadd, C.-J. (1983). Järn och potatis: jordbruk, teknik och social omvandling i Skaraborgs län 1750–1860. Göteborgs Univ.

- Gadd, C.-J. (2000). Det svenska jordbrukets historia III. Den agrara revolutionen: 1700–1870. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur/LT.

- Gadd, C.-J. (2011). The agricultural revolution in Sweden, 1700–1870. In J. Myrdal & M. Morell (Eds.), The Agrarian History of Sweden. From 4000 BC to AD 2000 (pp. 118–165). Nordic Academic Press.

- Granér, S. (2002). Samhävd och rågång: om egendomsrelationer, ägoskiften och marknadsintegration i en värmländsk skogsbygd 1630–1750. Göteborgs Univ.

- Hallberg, E. (2013). Havrefolket. Studier i befolknings-och marknadsutveckling på Dalbosläten 1770–1930. Göteborgs University.

- Havinden, M. (1961). Agricultural progress in open-field Oxfordshire. Agricultural History Review, 9(2), 73–83. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40272969

- Heckscher, E. F. (1945). Det svenska jordbrukets äldre ekonomiska historia. En skiss. Ekonomisk tidskrift, 47(3), 197–224. doi:10.2307/3438368

- Heckscher, E. F. (1946). Skiftesreformen under 1700-talet än en gång. Ekonomisk tidskrift, 48(1), 45–51. doi:10.2307/3438253

- Heckscher, E. F. (1949). Sveriges ekonomiska historia från Gustav Vasa, II:1. Stockholm: Bonniers.

- Helmfrid, S. (1961). The Storskifte, Enskifte, and Laga skifte in Sweden. General features. Geografiska Annaler, XLIII(1-2), 114–129. doi:10.2307/520236

- Hoppe, G. (1997). Jordskiftena och den agrara utvecklingen. In B. M. P. Larsson, M. Morell, & J. Myrdal (Eds.), Agrarhistoria (pp. 254–270). Stockholm: LT.

- Isacson, M. (1979). Ekonomisk tillväxt och social differentiering 1680–1860: bondeklassen i By socken, Kopparbergs län. Diss. Uppsala: Univ.

- Jones, E. (1974). Agriculture and the industrial revolution. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Jupiter, K. (2020). The function of open fields: Agriculture in early modern Sweden. (Dissertation Sveriges Lantbruksuniv). Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae.

- Keele, L. (2010). Proportionally difficult: Testing for nonproportional hazards in Cox models. Political Analysis, 18(2), 189–205. doi:10.1093/pan/mpp044

- Kerridge, E. (1967). The agricultural revolution. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Kleinbaum, D. G., & Klein, M. (2012). Survival analysis: A self-learning text (3rd ed.). Springer.

- Lägnert, F. (1955). Syd- och mellansvenska växtföljder I. De äldre brukningssystemens upplösning under 1800-talet. Gleerup.

- Morell, M. (1992). Småbruket, familjejordbruket och mekaniseringen. Aspekter på det sena 1800-talets och det tidiga 1900-talets svenska jordbruk. In B. Larsson (Ed.), Bonden i dikt och verklighet (pp. 62–116, 149–150). Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Morell, M. (2001). Det svenska jordbrukets historia IV. Jordbruket i Industrisamhället. Natur & Kultur/LT.

- Nyström, L. (2019). Scattered land, scattered risks? Harvest variations on open fields and enclosed land in Southern Sweden c. 1750-1850. Research in Economic History, 35, 165–202. doi:10.1108/S0363-326820190000035008

- Nyström, L., & Hallberg, E. (2018). Two parallel systems: The political economy of enclosures and open fields on the plains of Västergötland, Western Sweden, 1805-65. Historia Agraria. Revista de Agricultura e Historia Rural, Sociedad Española de Historia Agraria, 76, 85–122. doi:10.26882/histagrar.076e03n

- Olai, B. (1983). Storskiftet i Ekebyborna. Svensk jordbruksutveckling avspeglad i en Östgötasocken. Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Olai, B. (1987). “ … till vinnande af ett redigt Storskifte … ”: En komparativ studie av storskiftet i fem härader. Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Olsson, M. (2005). Skatta dig lycklig. Jordränta och jordbruk i Skåne 1660–1900. Gidlunds.

- Olsson, M., & Svensson, P. (2010). Agricultural growth and institutions: Sweden, 1700–1860. European Review of Economic History, 14(2), 275–304.

- Overton, M. (1996). Agricultural Revolution in England: The transformation of the Agrarian Economy 1500–1850. Cambridge University Press.

- Pettersson, R. (1983). Laga skifte i Hallands län 1827–1876: förändring mellan regeltvång och handlingsfrihet. Stockholm: Diss. Stockholm : Univ.

- Pettersson, R. (2003). Ett reformverk under omprövning, Skifteslagstiftningens förändringar under första hälften av 1800-talet. Kungl. Skogs- och lantbruksakademien.

- Schön, L., & Krantz, O. (2016). New Swedish historical national accounts since the 16th century in constant and current prices. Department of Economic History, Lund University.

- Therneau, T. M., & Grambsch, P. M. (2000). Modeling survival data: Extending the Cox model. Springer.

- Thulin, G. (1890–1935). Om mantalet. Nordstedt.

- Turner, M. E. (1980). English parliamentary enclosure: Its historical geography and economic history. Archon Books.

- Utterström, G. (1957). Jordbrukets arbetare: levnadsvillkor och arbetsliv på landsbygden från frihetstiden till mitten av 1800-talet. Tiden.

- Van Zanden, J. L. (1999). Chaloner memorial lecture: The paradox of the marks. The exploitation of commons in the eastern Netherlands, 1250-1850. The Agricultural History Review, 47(2), 125–144. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40275568

- Wiking-Faria, P. (2009). Freden, friköpen och järnplogarna: drivkrafter och förändringsprocesser under den agrara revolutionen i Halland 1700–1900. Göteborgs University.

- Widgren, M. (1997). Bysamfällighet och tegskifte i Bohuslän 1300–1750. Uddevalla: Bohusläns museum.

- Yelling, J. A. (1977). Common field and enclosure in England 1450–1850. London: Macmillan.