Abstract

Implementing discovery tools and getting them to work with existing library services often leaves very little time for their promotion and for the thoughtful, ongoing evaluation and curation of their content. However, the expectations and experiences that users have about discovery tools are often directly related to the content and the way that content is described. In our efforts to work with vendors to resolve the underlying business issues that prevent us from having all of the metadata for our resources included in our discovery tools, we may have lost sight of our role in curating and evaluating the usefulness of the content that is already included in them.

Discovery tools have been around for a few years, and much has been written about their pros and cons, how to implement them, and the student and librarian response to them. Implementing these tools is a significant financial investment for many libraries, and it requires a lot of library staff time to install them, get them to work with existing library services, address usability issues, brand and promote them, and even overcome objections to them. This often leaves very little time to think about the best way to curate and manage their content, beyond the initial question of “is resource x included”? While there are ongoing efforts to work with vendors to resolve the business issues that prevent libraries from having all of the metadata for their resources included in these discovery tools, librarians still need to embrace a curatorial role with regard to the content that is already included in these tools, focusing on its usefulness and relevance to users, and the way in which it represents the collection as a whole.

Ideally, discovery tools should provide access to all of the library’s collections and break down the access point silos, allowing users to have a Google-like experience with library resources. The idea of this universal access is described through the concept of “inclusion.” It is very common to ask if a resource is included in a discovery tool, and this is a surprisingly hard question to answer. In part, this is because there is not a consistent understanding among library staff of what “inclusion” means. Does it mean the metadata straight from the article, or the metadata from another index which has the article metadata? Does it mean the basic metadata for the conference proceeding, or the subject headings and keywords that come with it? Is it the container information itself, or information about what the container describes, that is really important? Does inclusion mean the resources for which the library pays, or also free resources to which the library provides (or is able to provide) access?

When thinking about discovery from this perspective, several challenges emerge. The most obvious one is that the content provider of a resource may choose not to share their metadata with the discovery provider at all or in any fashion. This is a well-known issue and it is being addressed and advanced by the Open Discovery Initiative (ODI) of the National Information Standards Organization (NISO).Footnote1 However, the inclusion problem is actually much more complicated. A library may subscribe to content; the content provider has shared their metadata with the discovery provider, yet something is still lost in translation, for one of the following reasons:

Content in the native resource is not represented in the same way in the discovery tool and cannot be selectively activated in the discovery tool. For example, the library may selectively subscribe to ebooks in a package, but within the discovery tool administrative interface, it is not possible to activate individual books, only the metadata for the entire package. There may be no way to selectively activate those things to which the library subscribes within this larger container.

A subscription that appears as a complete entity to the library is actually made up of components which the vendor has aggregated, and the metadata for some of these underlying components are not made available to the discovery provider.

The date coverage for the content in the native resource is not matched in the discovery tool because the content provider has agreed to provide only partial coverage to the discovery provider.

The content is updated in the discovery tool less frequently and unpredictably than in the native resource, so inclusion of metadata is delayed.

Anyone who has tested content searches in both the native and discovery interfaces can attest to the frustration of trying to explain the differences in search results and the subsequent difficulties in communicating why these differences exist to other library staff. Knowing all of the problems related to inclusion issues, is it possible to let go of this idea of total inclusion and focus on what is worth activating? (i.e., what is “newsworthy?”)

DISCOVERY TOOL CONTENT USAGE AT HESBURGH LIBRARIES

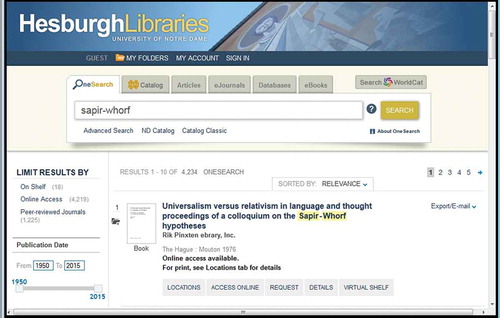

The Hesburgh Libraries at the University of Notre Dame implemented Primo Central Index (PCI) in 2012 and launched it officially as Onesearch in the fall of 2012. Initial attempts to understand how users were engaging with the content involved examining link resolver request and clickthrough data for 2013 to determine which content provider records were used the most, where “usage” is a click by the user, or a request, for the full-text of an item. This was tracked by a report available in the link resolver administrative interface, which showed a source id that could be mapped to individual resource collections activated within PCI. This data was useful to show engagement with a particular collection, but it only showed that a user clicked on one link. In the fall of 2014, as a result of some changes made to the search interface of Onesearch, Google Analytics event tracking was implemented. The event tracking was applied to tabs of content records in the discovery tool and links available within those records. The options for the user via these tabs and links include ways to access the full text of the record item, or to request that item through document delivery or interlibrary loan. Other options available to the user include exports to reference manager tools, e-mail and print options, as well as links for related content and more detailed information about the resource being described in the record. below shows a sample record in Onesearch.

From a review of the event-tracking data for these options from November 2014–February 2015, several themes have emerged.

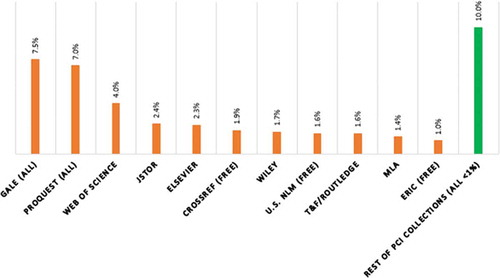

CATALOG VERSUS ARTICLE METADATA USAGE

The content records which had the most events triggered for this time period came from local catalog records, which include HathiTrust records and records from two smaller partner libraries. Catalog records represented approximately 58% of all events tracked. Of the remaining 42% of events, approximately 32% came from ten of the activated resource collections in the discovery tool, while 10% were for other resource collections (the “long tail”), which individually had less than 1% of events. There are over 150 active collections in PCI. These ten collections, which represented 32% of events for non-catalog records, included publisher-provided collections, A&I index collections, and services such as Crossref, and included a variety of indexing depth. Several of the collections were not subscription resources for the library. It is important to note that because of deduping algorithms applied by the discovery tool, there could be significant overlap between these collections that triggered events in those collections which also index the same content. However, this data does indicate the content itself that is actually being used and has triggered interest in the form of clicks for full-text or other requests for the item or about the item. This could be very useful for collection development efforts because it provides information on the content itself that is of interest, not just which collection happens to index it. shows the list of these 10 highly used collections in Onesearch.

FULL-TEXT PROVISION VERSUS EXPLORATION

The types of events triggered across all content provider records were also examined to see if they could indicate an overall pattern of discovery content usage. All of the events tracked are represented by links in the content provider records, and were categorized as a way to determine which events for which content collections might be most useful.

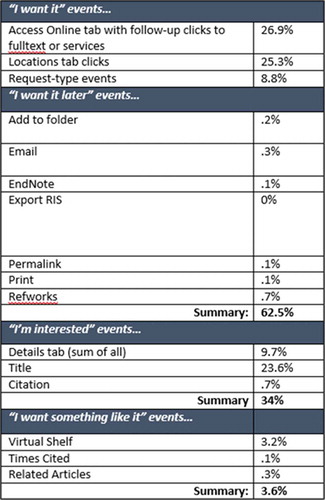

For example, for the same time period, November 2014-February 2015, “I want it” type events generated 62.5% of all events across activated collections. “I want it” events include clicks on links that indicate that the indexed content is of interest enough to motivate the user to obtain it. They included clicks on the Access Online tab shown in , with follow-up clicks on the full-text or services options that are presented; clicks on the Locations tab, and request-type events such as document delivery or request through interlibrary loan events.

This category of events also contained a subset of “I want it later” events, which included additional functions or options available from the record which indicated that the user was interested in the content and wanted to either print the record, add it to a folder, e-mail it, or export it to a reference management tool such as RefWorks. This subset represents a fraction of the total events, about 1.5%. The “I’m interested” category of events were triggered both in conjunction with, and independently of, the “I want it” events, and the progression of them can be tracked at the content collection level to see what users do with a record from that collection in response to the actual search string that they used. This could be useful if some content collections showed a high level of “I’m interested” events, where users are clicking on the Title or Details tab of the record, but chose not to follow through to the actual item, or chose not to order the item through interlibrary loan.

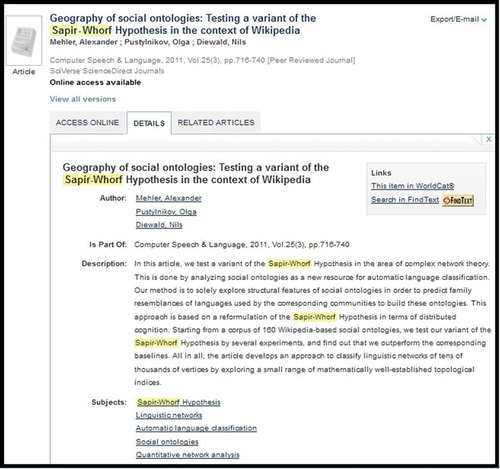

The last event category in , “I want something like it,” includes user clicks on options such as the Virtual Shelf shown in and other links, such Related Articles and Times Cited, which offer the user the option to explore or link to similar content to the record he or she is currently viewing. The “I want something like it” events make up a very small proportion of total events for the time period, only 3.6%. Related to this category are links that were clicked from within the Details tab that provide more granular data on what users are doing when they are interested in the record. Links provided from this tab for things like author, subject, Worldcat, and so on were clicked on very infrequently, and this subset of the Details tab event data represented less than 1% of all events. provides an example of the Details tab links for a Onesearch record.

REFERENCE CONTENT USAGE

An analysis of events for specific collections provides more detailed information on how users interact with that resource as it is presented in the discovery tool. Although much of the content currently activated in the library discovery tool is for book or article-level metadata, there are several reference or tertiary literature resources. Given the nature of this type of content, it was theorized that some of the events might be more exploratory in nature and perhaps indicate a different type of usage pattern, such as clicks on subject links. An analysis of one of these resources, Encyclopedia Britannica, which was ranked 24 in terms of total events overall for the time period, did not indicate this. The events were primarily directed toward gaining the full-text of the content via a direct link from the record to the native resource. In addition to the events, the search terms used with this resource were examined. About five of the search strings used included the term “encyclopedia” or “encyclopedia Britannica,” indicating a more known-item type of search for a particular resource, combined with a keyword. The majority of the search strings did indicate what is considered to be more unknown-item or topical, exploratory searching.

INTERPRETATION OF EVENT TRACKING DATA

The current sampling of event tracking data for discovery tool events, along with an analysis of search terms associated with content collections and events, seem to indicate that users are employing Onesearch more for known-item searches, in particular for specific articles, than for exploration of topics or as a tool for research and discovery. This could be due to a number of factors, including how the tool is integrated into the library website, the way it is branded, the small amount of tertiary literature that is currently available and indexed in the tool, the links and options available to the user within a record, and the user’s expectations of the tool. The very low usage of additional services such as exports to research tools, e-mail and printing seem to indicate a mentality of “just passing through” to full-text or to another library resource. In particular, the much higher usage of local catalog records could indicate that users regard the tool as a substitute for the library catalog, although some of this higher usage can be attributed to the “boosting” of catalog records in the Primo Central Back Office. Still, even taking this into account, it raises these questions: Do users understand the tool they are using, and its scope and its limitations? Do they use it to find more than explore or discover?

The small number of non-catalog collections that trigger events, compared to the number that are currently activated, could indicate a significant indexing overlap, which is deduped into one record that triggers the event, and the algorithm for that deduplication could be the determining factor in which article collection record gets clicked on. However, the content that is being used is still very small in proportion to the amount of unique content that is available for discovery, regardless of where it is being indexed. Additionally, a sampling of approximately 4,000 search terms from this time period seems to indicate a preponderance of known-item, article-title searching, implying that users are getting lists of article somewhere else such as Google Scholar or a course list, and coming to the library to see if it is available electronically.

ADAPTING APPROACHES TO CONTENT INCLUSION

The following approaches constitute a first pass at developing some guidelines for content curation, based on the usage and search data recently reviewed and presented.

Provide maximum coverage for known-item searches. Most of the known-item searching for non-catalog records included complete or partial article titles, or an article title combined with the article author. Depending on the indexes that the library subscribes to, and the years of publications that are indexed, it may be necessary to activate several different types of collections or resources, that is, publisher-provided metadata, A&I indexes, and services such as CrossRef, to provide coverage for complete journal runs and for as much of the scholarly output as possible.

Think about incorporating “pointer” resources. Including research guides, subject guides, LibGuides, and so on, in the discovery tool may help provide a way to balance the collection with resources that highlight more tertiary or secondary literature and provide assistance with more topical, exploratory search terms. In addition, including records for known tools, such as other database or indexes like PubMed, MLA, Web of Science, and so on, or services, such as interlibrary, course reserves, or document delivery, or even library hours, may help users who are confusing the discovery tool with a website search mechanism and allow them to branch out into other collection resources or library services from the discovery tool.

Reduce overlap as much as possible. Although discovery tools do provide a great deal of deduplication, there is still a lot of overlap that cannot be deduped because of small differences in the records. In particular, looking at overlap between publisher collections for article metadata, A&I indexes and CrossRef may help make the workflow part of content activation easier in the long run, since maximum coverage for a journal could possibly be achieved through one of these collections of metadata. Reducing overlap as a general principle may allow for the surfacing of more unique content and other information formats, including multimedia, and can prevent unwanted “noise” or duplication for the end-user.

The deeper understanding of what inclusion really means, combined with this initial analysis of content that is actually being used within Onesearch, has led to a reframing of the question “is it included?” Perhaps a better question for libraries to ask is what does discovery really mean to the institution, and do the resources in this tool help users to find specific, known-items as well as provide a starting point of exploration of the library’s collection and services? And how useful is the content to users, and what methodologies can we develop to periodically evaluate this, both quantitatively and qualitatively? Moving away from a strict focus on resource inclusion to this type of inquiry may prove more beneficial to library users in the long run.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Monica Moore

Monica Moore is an Electronic Resources Librarian, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA.

Notes

1. National Information Standards Organization, “Open Discovery Initiative: Promoting Transparency in Discovery,” http://www.niso.org/apps/group_public/download.php/14820/rp-19-2014_ODI.pdf (accessed June 14, 2015).