Abstract

This study focused on how serials information for journal articles is presented based on a sampling of institutional repository platforms at a variety of institutions. Since metadata on journal articles in institutional repositories can often be incomplete and haphazard, not only due to the difficulty of entering the metadata in the first place, but due to the difficulty of adapting existing metadata schemes to represent a journal article accurately, how can libraries increase the discoverability of these individual articles from a wide variety of journals? By examining existing metadata schemes and how they are used to represent articles currently in institutional repositories, libraries can look for a way forward to better represent articles though adapting schemas, exploring possibilities for standardization of metadata for articles, and promoting good practices.

INTRODUCTION

The electronic resource librarian at a small library is often responsible for maintaining a wide variety of library technologies, and, consequently, will strive to make all of the library’s discovery tools perform as effectively as possible. An institutional repository may seem like an impossible project for such a small library, given the technical requirements of setting up and maintaining an institutional repository platform. Catholic Theological Union (CTU) is a stand-alone graduate theological school with a small faculty whose work is published primarily in monographs, and might seem to have a limited scope for an institutional repository. However, our library is committed to providing the broadest access to the theological literature for the widest possible audience, and for this reason we felt it was a priority to make this contribution through an Open Access repository.

Due to our advocacy for Open Access policies for journals, which is also manifested through our publishing program for two Open Access journals, we knew we would be concentrating on helping faculty deposit journal articles in our institutional repository. The library had already begun researching archiving policies in the SHERPA/RoMEO database for particular journals where faculty work had been published in order to better educate the faculty regarding the extent of all of their self-archiving rights. The archiving information about specific journals in this database demonstrated that there were a number of theology journals that allowed archiving in institutional repositories, which meant that librarians and faculty could begin the process of depositing articles into the library’s institutional repository as soon as it was set up in the fall of 2014. Due to limited funds, the library chose CONTENTdm as the platform for the institutional repository since this platform was already included in the library’s FirstSearch subscription through the state library.

Before selecting this particular platform, however, the library had investigated a number of other platforms, including DSpace and Islandora, as part of an effort to launch a shared institutional repository with a number of other Chicago area theological institutions. Although the proposal for a shared repository was unsuccessful, the library still has hopes that a shared repository, or even a disciplinary repository for theology and religion, might be a possibility in the near future. Consequently, the library was concerned with the prospect of harvesting the metadata from the beginning of the institutional repository project, so we sought to establish guidelines for our own metadata entry for journal articles that assumed that the metadata would be harvested and reused in some fashion.

SELECTING METADATA SAMPLES FROM INSTITUTIONAL REPOSITORIES

Besides looking at recommended practices for shared metadata in institutional repositories, I decided it was important to examine samples of journal article metadata in specific repositories to better inform our own metadata guidelines with real-world examples. The focus of my sampling was to examine descriptive metadata in various repositories to establish good practices for our own repository in order to offer the fullest description of the article for the purpose of harvesting and reusing metadata in other repository platforms, as well as to consider the discoverability of our metadata on the open web by tools such as Google Scholar. The focus of the sampling of metadata was descriptive metadata, particularly Dublin Core, since this is the metadata schema used by CONTENTdm. The intent of the study was to explore how Dublin Core can actually be used, rather than examine metadata for the purpose of establishing parameters for quality records. Other studies of institutional repositories are available that establish criteria for quality that include completeness, accuracy, and consistency.Footnote1 However, the primary concern I had with examining samples of metadata as far as completeness was concerned was how to describe the journal where the article originated, since this information can be difficult to express using the Dublin Core elements. Dublin Core is intentionally flexible; all elements are optional and all are repeatable, with the intention that the schema be used to describe every conceivable format. This aspect of Dublin Core demonstrated that it was both a strength and a weakness in my study of metadata examples from institutional repositories.

The primary standard of comparison for completeness that I used when reviewing the metadata samples was the traditional elements of a citation that students need to cite an article. The traditional citation elements of article title, author, journal title, volume number, issue number, page range, and date are also the elements that indexing and abstracting services have provided as the minimum descriptive information for the journal articles that they provide in their databases. Since I was also concerned with discoverability outside of the institutional repository itself, particularly on the open web, I also wanted to examine how well the metadata for journal articles complied with Google Scholar’s recommendations.

Google Scholar’s guidelines for metadata in institutional repositories progress from the maximum recommended information to the minimum information. For instance, the maximum recommended information using the Highwire Press tags for the article includes citation_title, citation_author, citation_publication_date, while the journal itself is described in the tags citation_journal_title, citation_issn, citation_volume, citation_issue, citation_firstpage, and citation_lastpage. These Highwire Press tags have Dublin Core elements that Google considers to be equivalents, such as DC.creator for citation_author, although Google recommends using Dublin Core as a last resort, since “Dublin Core tags (e.g., DC.title) … work poorly for journal papers because Dublin Core doesn’t have unambiguous fields for journal title, volume, issue, and page numbers.”Footnote2 The minimum recommended metadata tags, regardless of the schema, are article title, first named author, and the publication year. If an institutional repository is not able to provide the appropriate metadata tags at all, the recommendation is that the Portable Document Format (PDF) formatting for the article include an article title in at least 24 pt. font, the author’s name in 16–23 pt. font, and a full bibliographic citation for the article in either the header of the footer on the page.

In order to find samples of metadata from a variety of repositories, I used the OpenDOAR directory to select a sample of institutional repositories that used the most popular repository platforms. I choose institutional repositories that were relatively large, since I also wanted to look for existing documentation about article metadata, and it seemed large institutions would be more likely to have publically available documentation. The directory information that was most interesting for our library’s purposes was policies related to metadata sharing, including Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) harvesting capability. The OpenDOAR directory lists metadata sharing policies using the OAI-PMH Identify response to gather information programmatically, but the directory staff will also review repository web pages for specific “Policies” or “About” pages that may provide the needed information. Policies are analyzed according to specific criteria and graded to make it easier to compare policies across institutions.Footnote3 Including repositories in the sample set that allowed re-use was important for our library, since metadata re-use was a key factor for our own institutional repository, and we wanted to model metadata from repositories that expected their metadata to be re-used and shared. Of the selected repositories from the sample, Columbia University, e-LIS and the University of Nebraska–Lincoln allowed commercial reuse, the University of Queensland allowed non-profit use, and the rest were undefined. This designation did not necessarily mean that reuse was not allowed, but that the institution did not specify conditions for reuse in their publically available policies.

The repositories represented in OpenDOAR focused on articles and Electronic Thesis and Dissertation (ETDs), according to the aggregated statistics on format provided on the website.Footnote4 A recent study published by Moulaison, Dykas, and Gallant also confirmed that these two types of material are the most commonly collected in institutional repositories.Footnote5 This was helpful for our library, since our repository is also focused on articles and ETDs, so the expectation was that most institutions employed metadata practices that took into account these two formats. Besides examining metadata samples from the selected repositories, the library also examined any publically available documentation regarding metadata practices. Of the selected repositories, all provided basic instructions for contributors, but I was unable to find detailed documentation regarding metadata policies and procedures.

Since the focus of the publically available metadata documentation was on contributors rather than library staff, the source for determining metadata standards had to be the institutional repository records themselves. In order to compare the metadata in a standard way, preliminary comparisons of records began with the metadata in the <meta> tags in the <head> element. This was helpful for two reasons. One was that not all of the institutional repositories provided a staff view, so the actual metadata could not be examined and compared appropriately. The other was that the metadata displayed in the <meta> tags represented either Dublin Core unqualified elements or metadata tags from Google Scholar’s recommended metadata schemas, though often tags from both Dublin Core and one other schema were represented. Since the focus of the comparison was identifying metadata practices that would increase discoverability in Google Scholar or be useful for sharing metadata through means such as OAI-PMH, focusing on how the metadata would appear to either a search engine like Google or an OAI-PMH harvester was a helpful exercise. The OAI-PMH protocol is based on the Dublin Core schema; generally speaking, OAI harvesters will only harvest unqualified Dublin Core. In other words, while qualified Dublin Core may be used in a particular institutional repository and provide both additional descriptive information and searching functionality, once harvested, the metadata may lose the additional information provided by qualifier.

EXAMPLES OF METADATA FROM INSTITUTIONAL REPOSITORIES

The records sampled included journal articles deposited in the institutional repositories at seven libraries. E-LIS, a disciplinary repository for library and information science, was also included so as to provide a comparison with a repository using the Eprints platform. See .

Table 1. Repositories Sampled

All of the repositories sampled included either Dublin Core metadata, Highwire Press tags, EPrint tags, bepress tags, or, in some cases, both Dublin Core and one other type of tag. The University of Michigan and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) included both Dublin Core metadata and Highwire Press tags, since both repositories use the DSpace platform, and Highwire Press tags are incorporated in the metadata schema for DSpace.

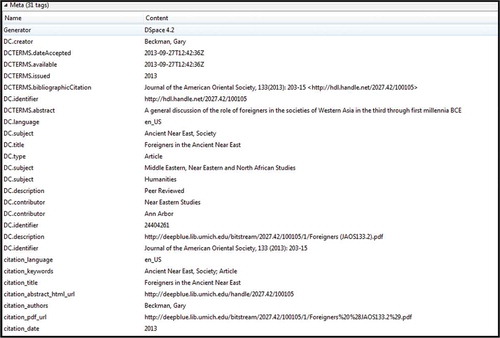

The University of Michigan repository, Deep Blue, uses the DSpace repository, which generates both Dublin Core qualified metadata as well as Highwire Press tags. DSpace conventions for metadata include DC.type “Article” as well as Highwire Press tags such as citation_title, as seen in the example in .

Dublin Core elements that specifically referenced identifying information about the journal where the article appeared included DCTERMS.bibliographicCitation and DC.identifier for the bibliographic citation, and DCTERMS.issued for the publication date. The automatic generation of Highwire Press tags is present in the most recent version of DSpace, provided the institution has not implemented significant customization of metadata fields. This is helpful for new installations of DSpace, but could mean that older records in some DSpace repositories do not make use of the Highwire Press tags.Footnote6 Another repository, Bielefeld University, also made use of Highwire Press tags, including citation_issn for the International Standard Serial Number (ISSN), and citation_pdf_url for links to both the repository version of the article and the publisher’s version—see .

Bielefeld’s repository also made use of the DC.identifier tag to enter the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) for the repository record for the article. Bielefeld University’s repository uses the LibreCat platform.

Two repositories, the University of Queensland and Columbia University, made use of Fedora as the platform for their institutional repository. Fedora incorporates the Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) metadata schema, but Fedora can also output Dublin Core and Highwire Press tags to the <meta> tags in the <head> element for each record. Both repositories represented the Highwire Press tags for article title, author, journal title, volume, date, firstpage, lastpage. The University of Queensland also included the citation_issn tag for ISSN, while Columbia included a citation_doi tag for the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) for the original version of the article and a second DOI in the citation_handle_id tag with the DOI for the version of the article represented in Columbia’s institutional repository.

Columbia University’s platform also supports a full metadata view that allows the underlying MODS metadata to be examined, while the University of Queensland has not deployed such a feature. MODS elements can easily represent a full article citation in discrete tags by nesting the information within a <relatedItem type = host> tag, as seen in .

Figure 3 Columbia University example of MODS tags for the host relatedItem, including journal title, volume, issue number, date, and page ranges.

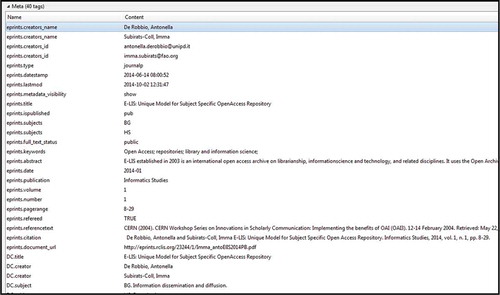

While Highwire Press tags feature prominently in the <meta> tags in most DSpace and Fedora repositories, metadata tags from other repository platforms, such as EPrints and bepress Digital Commons, are also used by Google Scholar. These repositories included e-LIS, which uses the EPrints platform, and the University of Nebraska–Lincoln repository, a bepress Digital Commons repository. Examples of Eprints tags recommended by Google Scholar that represented the journal where the article appeared included tags such as eprints.publication, eprints.volume, eprints.number, and eprints.pagerange—see .

The bepress Digital Commons platform included fewer <meta> tags in the <head> element, but did include bepress_citation_author, bepress_citation_title and bepress_citation_date—see .

A full article citation and DOI did appear in the public record display, but not in the <meta> tags. According to Google Scholar guidelines, the minimum recommendation for the <meta> tags are title, author and date. The typical Digital Commons PDF in this repository also complies with Google Scholar’s font recommendations to support discoverability for article PDFs, such as a prominent title and a complete citation at the bottom of the first page.

MOVING FORWARD WITH METADATA PRACTICES FOR CTU’S INSTITUTIONAL REPOSITORY

While many of the examples included the metadata tags recommended by Google Scholar, these tags remain unavailable for use in a CONTENTdm repository such as ours, which only supports Dublin Core metadata. In CONTENTdm, the Dublin Core elements are is not represented in <meta> tags in the <head> element for individual records. While we would have preferred the specificity of the MODS schema, which could represent not only the journal title but the full volume, issue, date and page range information, the library will enter as much information about the individual citation elements in separate metadata fields as allowed by the parameters of Dublin Core. Our initial metadata guidelines for journal articles specified using the DC.identifier element to enter the DOI for the original article and the DC.bibliographicCitation element to enter a complete citation for the article. After the examination of the examples in this study, the library added the Relation-IsPartOf qualified element for the journal title. Besides entering the DC.identifier for the DOI, the identifier element will be repeated in order to record the ISSN, using the practice of including the label ISSN: in front of the ISSN number.

Another element that can be repeated is the DC.type element, using terms from two vocabularies. The usefulness of vocabularies with regard to journal articles is just beginning to be utilized by institutional repositories. Dublin Core includes recommendations for specific vocabularies within particular elements, such as the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) Vocabulary for the DC.type element, but other vocabularies not specifically mentioned may be used, and it is the intention of the guidelines that other vocabularies should be used when deemed necessary by the needs of particular user communities.Footnote7 While specific documentation for the vocabularies used by the repositories was not accessible, based on the terms the metadata examples used to describe articles, the library adopted the Eprints Type Vocabulary Encoding Scheme to specify the DC.type property as “Journal Article.”Footnote8 This vocabulary will be useful for other types of resources, so its use will be incorporated into the library’s practices for entering metadata for other formats. This vocabulary did not replace the DCMI Vocabulary; for our repository, the DC.type property is repeated using the “text” label from the DCMI.

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS FOR REUSING AND SHARING INSTITUTIONAL REPOSITORY METADATA

While our library’s present concern is creating metadata that describes the journal articles as completely as possible, we would like to explore how the metadata might be used not only for discovery, but for extending library services to patrons. One possible service could be to integrate versions of articles in institutional repositories into both discovery and delivery systems used by libraries, particularly interlibrary loan and document delivery. Several institutional repositories, such as Bielefeld University, University of Prince Edward Island, and University of Queensland designated some journal articles as in press or pre-print versions, but how this information was represented in the metadata, and thus the possibilities for the sharing of that metadata, was not discernible. The University of Queensland repository has implemented a metadata field to indicate compliance with their institution’s open access mandate, thus indicating either a post-print or a publisher’s PDF, although this information would need to be programmatically available if institutional repository article versions were to be more fully integrated into library discovery mechanisms.Footnote9 In another example, the MIT repository represented the version of the article using the qualified DC element DC.relation.isversionof for the DOI of the publisher’s version in tandem with the dc.eprint.version element to indicate that a particular article was the final published version. Again, this information is helpful for determining the version of the article that is available once the item has been retrieved, but only after the retrieval from within the institutional repository itself. Google Scholar, for instance, can link to institutional repository article versions, and link resolvers can often link to Google Scholar through keyword title searches for the article, but there is much potential for fuller integration of metadata into some future library discovery system that could distinguish between article versions, and thus assist library patrons in choosing the most appropriate version for them.

Other services that institutional repositories could support are citation management tools like Zotero. Zotero relies on four methods for detecting bibliographic information and saving the appropriate metadata about the item. These methods are CoinS, embedded metadata, DOIs, and retrieving metadata from a PDF.Footnote10 Repositories that would like to see their metadata work most effectively with Zotero could review their repository platform to see how well it complies with the technical requirements for each method, and could also conduct tests by saving metadata to Zotero to see whether the information transferred represents a complete journal article citation.

If the repository platform itself was difficult to customize for compliance with Zotero’s guidelines, other strategies could be used to increase interoperability with Zotero. One strategy is to comply with Google Scholar’s guidelines with the goal of increasing the coverage of the institutional repository’s content in Google Scholar. Zotero’s tool to retrieve metadata from a PDF is dependent on Google Scholar—if a PDF copy of an article is saved to Zotero from an institutional repository, and that same article has a citation in Google Scholar, then Zotero’s retrieve metadata tool should be able to pull the complete citation for the article. While improving the accuracy of metadata saved to Zotero from an institutional repository may mostly be a matter of trial and error, including certain kinds of identifying metadata seemed to improve results in Zotero in some tests with our library’s institutional repository. For example, adding DOIs that included the full URL in our CONTENTdm instance seemed to increase the likelihood that the resulting citation in Zotero accurately reflected the full citation information for a journal article.

CONCLUSION

While the purpose of our library’s review of metadata samples was to establish basic input guidelines for our own metadata, sharing both our metadata and our metadata practices will not only assist other libraries, but will inform our own policies and procedures as we move forward with our institutional repository. The library is expanding its internal wiki documentation to provide basic metadata education for contributors and to outline institutional repository procedures, information that may also be of interest to other libraries. This documentation will become a part of a policies page for the institutional repository on the library’s website. Including information about OAI-PMH harvesting on a policies page will also make it possible for the library to fully complete the registration information requested by the OpenDOAR directory, and the directory itself has provided a baseline of metadata sharing issues that need to be considered when establishing policies. Moving forward, the library plans to continue to make metadata available passively through harvesting, but we also hope that we will be able to harvest our own metadata and actively share it with a larger discovery project. By sharing both our metadata and our metadata practices, the library’s ultimate goal is to more effectively share the full content of our institutional repository with a broader audience.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lisa Gonzalez

Lisa Gonzalez is Electronic Resources Librarian at Catholic Theological Union at Chicago.

Notes

1. Mary Kurtz, “Dublin Core, DSpace, and a Brief Analysis of Three University Repositories,” Information Technology and Libraries 29, no. 1 (2013): 40–46. https://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/ital/article/view/3157 (accessed May 22, 2015).

2. “Google Scholar Inclusion Guidelines for Webmasters—Indexing,” http://scholar.google.com/intl/en-US/scholar/inclusion.html#indexing (accessed May 22, 2015).

3. “OpenDOAR Charts—Worldwide: Metadata Re-Use Policy Grades,” http://www.opendoar.org/find.php?format = charts (accessed May 22, 2015).

4. “OpenDOAR Charts—Worldwide: Most Frequent Content Types,” http://www.opendoar.org/find.php?format = charts (accessed May 22, 2015).

5. Heather Lea Moulaison, Felicity Dykas, and Kristen Gallant, “OpenDOAR Repositories and Metadata Practices,” D-Lib Magazine 21, nos. 3/4 (March/April 2015). doi:10.1045/march2015-moulaison (accessed May 22, 2015).

6. “Search Engine Optimization,” DSpace 4.x Documentation—DuraSpace Wiki, https://wiki.duraspace.org/display/DSDOC4x/Search+Engine+Optimization (accessed May 22, 2015).

7. “DCMI Metadata Terms—Type,” http://dublincore.org/documents/dcmi-terms/#terms-type (accessed May 22, 2015).

8. “Eprints Type Vocabulary Encoding Scheme,” JISC Digital Repository Wiki, http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/repositories/digirep/index/Eprints_Type_Vocabulary_Encoding_Scheme (accessed May 22, 2015).

9. Sharon Bunce, “Open Access: UQ eSpace,” UQ Library Guides, http://guides.library.uq.edu.au/open-access/uq-espace (accessed May 22, 2015).

10. “Exposing Your Metadata,” Zotero, https://www.zotero.org/support/dev/exposing_metadata (accessed May 22, 2015).

APPENDIX: REPOSITORY RECORDS SAMPLED.