Abstract

In light of the economic, political and social significance of the middle class for South Africa's emerging democracy, we critically examine contrasting conceptualisations of social class. We compare four rival approaches to empirical estimation of class: an occupational skill measure, a vulnerability indictor, an income polarisation approach and subjective social status. There is considerable variation in who is classified as middle class based on the definition that is employed and, in particular, a marked difference between subjective and objective notions of social class. We caution against overoptimistic predictions based on the growth of the black middle class. While the surge in the black middle class is expected to help dismantle the association between race and class in South Africa, the analysis suggests that notions of identity may adjust more slowly to these new realities and consequently racial integration and social cohesion may emerge with a substantial lag.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Apartheid has left its scar on South Africa's social landscape. Almost two decades after the first fully inclusive elections in 1994, society continues to be characterised by a lack of social cohesion and economic injustice due to the persistence of race as a marker and a sorting mechanism in many dimensions of daily life, including geographical space, educational opportunities, the labour market, social networks and political party affiliation.

However, the post-apartheid period has also seen rapid growth of the middle class and a further expansion of the black middle class, building on the rapid increase between 1969 and 1983 documented by Crankshaw (Citation1997). These developments have been interpreted as signs that race may be gradually be becoming disassociated from class. A growing and more racially representative middle class can help shape a more just, dynamic and integrated society.

Theory and previous empirical findings suggest that an expanding middle class can boost economic efficiency and growth, can enhance the effectiveness and the stability of democratic institutions and political processes, and can help to mend social fragmentation and polarisation. There are also arguments that a growing middle class can have a direct impact on social cohesion, seemingly based on the intuition that a larger middle group would often imply lower polarisation and would serve as a buffer between the rich and the poor.

Within the South African context it is of course significant that a large share of the new middle-class members is non-white: both from a retrospective viewpoint, as evidence that some of the post-apartheid reforms have been successful in creating a more just and dynamic society, but also from a prospective viewpoint, as a catalyst for further social change.

Owing to the economic, political and social significance of class for South Africa's emerging democracy, it is important and interesting to estimate the magnitude of the growth of the middle class, and specifically the black middle class. However, such attempts are frustrated by disputes around the origins and meaning of class and how it should be measured. Lopez-Calva & Ortiz-Juarez (Citation2011a:1) highlight that empirical work on the middle class tends to assume that ‘thresholds that define relatively homogeneous groups in terms of pre-determined sociological characteristics can be found empirically’. Research on the middle class is often motivated by an interest in the political, economic and social benefits associated with the term, but without verifying whether the selected empirical approach is aligned with such conjectured benefits.

Using hyperbole and humour to highlight the proliferation of competing conceptualisations of the middle class, Beckett (Citation2010:1) refers to it as ‘a slippery business' that has in the past been associated with a long and divergent list of characteristics, including ‘having servants, renting a good property, owning a good property, owning a business, being employed in one of the professions, how you speak, how you use cutlery’ (Citation2010:1). This article acknowledges the contradictions and tensions in the menu of definitions and methods available for approximating the size of the middle class. It pursues a more critical and conceptually grounded approach. The next section presents a brief, but critical overview of contrasting conceptualisations of class and how this has affected studies on class in South Africa.

2. Estimating the size of the middle class in South Africa

The analysis of class is rooted in the pioneering work of Karl Marx and Max Weber (Marx, Citation1867; Marx & Engels, Citation1968; Weber, Citation1968). Marx defines class as shared structural positions within the social organisation of production. Class originates from shared interests and economic positions. The focus is on a conflict between the two main social classes: bourgeoisie (upper class) and proletariat (lower class). The bourgeoisie owns or controls the means of production (physical capital) while the proletariat does not and therefore needs to sell their labour to the bourgeoisie. Marx also distinguished a third class of petty bourgeoisie, which can be seen as a middle class. They are typically small business owners, shop-keepers, artisans and managers who are similar to the bourgeoisie because they are able to control (but not necessarily own) the means of production, but differ from the haute bourgeoisie because they work alongside their staff. Marx saw this group as a transitional class, which would eventually be absorbed into the proletariat.

In contrast, Max Weber saw shared life chances as the basis of class. Life chances were associated with opportunities for generating income in the market. Similar to Marx he also differentiates between those with access to property and land and those without, who have to earn their living through work. For those without property, their education, skills and knowledge determine their market value, their occupation and their wages, and in turn wages determine the lifestyle that an individual can afford. In this way, economic position maps to social status and shapes shared interests and social communities. However, while economic power, social status and political power are often correlated, Weber diverges from Marx by recognising that social status and political power are separate dimensions that are not always aligned with economic position and power. According to Weber, differences in social status can emerge due to ownership of the means of production, but it can also emerge due to other factors such as skills or credentials (Seekings, Citation2009).

Weber also distinguished the established class of property owners from the emergent middle class who were white-collar employees without property. However, in contrast to Marx, who saw this class as a temporary or transitional class that will eventually be absorbed into the proletariat, Weber expected the increasing bureaucratisation of administration to enhance the importance of specialist examination, creating a ‘universal clamour for the creation of educational certificates in all fields’ and leading to ‘the formation of a privileged stratum in bureaus and offices’ (Citation1961:241).

The concept of class has evolved much since the days of Karl Marx and Max Weber, but education, social status, income, wealth and shared life perspectives have remained central to definitions of class. One of the main enduring tensions is whether education or income is at the heart of the definition of class and the main transmission mechanism for the benefits of a growing middle class (Mattes, Citationforthcoming).

Despite debates around the relevance of the concept of classFootnote5 in current times, the term ‘middle class’ has continued to be popular amongst both researchers and the media. Recently, it has often been used to gauge the pace of social change and economic advancement in emerging and developing economies. In this literature, the term ‘middle class’ is frequently used as shorthand for increased agency and empowerment that allow individuals to competently navigate their own destinies and realise their own potential.

The term's enduring popularity and continued prominence appear to be partly due to a significant literature linking the middle class to a range of desirable country-level outcomes such as social cohesion, political stability and economic growth. Although authors are seldom explicit about the transmission mechanisms for such benefits, several analytical linkages have been frequently mentioned, including appeasement of the poor, increasing discretion in the use of money and time as basic needs are met, and a longer planning horizon due to greater stability in living standards. The combination of more discretionary income and a longer time horizon is expected to encourage investment in physical and human capital – both of which are traditionally viewed as important for stimulating economic growth because they improve productivity – and to enable the middle class to be more active and vocal in promoting accountability, good governance and the prioritisation of public goods such as education (Birdsall, Citation2010). Mattes (Citationforthcoming) distinguishes three different theories about how a larger middle class can strengthen democracy: through a more educated and skilled public-sector workforce; via the relationship between education and civic values; or by allowing a focus on free speech, civil liberties and democracy when basic needs have been met.

The interest in South Africa's social structure in general, and the middle class in particular, has spawned a large literature, much of which has had a strong Marxist focus. Seekings (Citation2009) points out that there were a number of Weberian scholars working on class in South Africa between the late 1940s and the early 1970s, but that this stream of work was abandoned and subsequently forgotten due to apartheid-era political considerations and sentiments that favoured a Marxist approach. The dominance of the Marxist approach led to the neglect of the relationship between class and Weberian concepts such as skill and social status. Although not explicitly Weberian, more recent research tends to highlight the role of Weberian concepts such as education and consumption (e.g. Rivero et al., Citation2003; Schlemmer, Citation2005; Seekings & Nattrass, Citation2005; Nieftagodien & Van der Berg, Citation2007; Seekings, Citation2007; Visagie & Posel, Citation2013).

There is consensus amongst the more recent studies that the middle class is expanding and that there has been a significant increase in the black share of the middle class (e.g. StatsSA, Citation2009; Van der Berg, Citation2010). While this growing disassociation between race and class has the potential to promote political stability and social cohesion, Schlemmer (Citation2005) concludes that the racial divide is still conspicuous – especially in areas where racial interests diverge, such as party politics, affirmative action and privatisation. He finds few close personal links across the racial divide. He also reports that there is no cohesive identity and coherence amongst the emergent black middle class. Many appear uncomfortable with the label and are reluctant to identify themselves as middle class.

Our analysis attempts to add to this existing literature by comparing rival conceptualisations of the middle class and assessing the overlaps and tensions between these definitions when applied to recent and representative South African datasets. In particular, in light of Schlemmer's (Citation2005) findings, we examine how well traditional externally defined measures of class align with individuals' subjective notions of their social position and class identity.

3. Data

Our analysis relies mainly on the 2008 National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) data, including approximately 7000 households. The survey contains detailed information on occupation, income and expenditure, assets and self-assessed social standing. We include the Project for Statistics on Living Standards and Development (PSLSD) of 1993 in the trend analysis where it was sufficiently comparable with the data from the three NIDS surveys.Footnote6

The second main data source is the last four waves (1995, 2001, 2006, 2013) of the World Values Survey (WVS). Each of the waves of the survey has a sample of approximately 3000 individual observations. This survey contains information on income brackets, occupations and assets and is unique due to questions on self-reported class, values, and attitudes.

4. Comparing rival approaches to estimating the middle class

We describe and implement the four main empirical approaches to defining the middle class – by skill or occupation, by vulnerability, by income and by self-identification – using the 2008 NIDS. This analysis is supplemented by work on the WVS, considering patterns in self-identification as middle-class members.

4.1 Occupation and skill level

There is a longstanding tradition of class analysis based on occupation and skill level (see for example Goldthorpe, Citation1987; Wright, Citation1980; Goldthorpe & Erikson, Citation1993; Evans & Millan, Citation1999) and consequently a fair degree of consensus has emerged regarding what occupations constitute the middle class (e.g. white-collar workers such as professionals, managers and clerks).

Internationally there are disputes about whether the middle class should include the self-employed (Wright, Citation1979, Citation1989; Glassman et al., Citation1993). In South Africa this question is also relevant because self-employment is often regarded as a last resort for those who cannot find salaried employment. The self-employed may therefore not be an elite group (as a Marxian analysis will often assume), but will include both highly skilled and unskilled individuals.

Furthermore, there are also concerns about accurately capturing and reflecting occupation and acquired skill. In settings with high unemployment rates and significant levels of underemployment, there may be a divergence between the productive characteristics and abilities of individuals and their occupation (Seekings & Nattrass, Citation2005). In some surveys there may be problems around reliable self-classification and missing values for occupational data.

A traditional shortcoming of occupational analysis is that the approach is unable to assign a class to any households with no employed household members, which is problematic in developing countries where this segment of the population may be a significant share. Seekings (Citation2003) proposes that in South Africa the unemployed may constitute a separate class due to the size of this group and the large divide in the living conditions and life chances of the unemployed and the employed.Footnote7 The frequent traffic out of unemployment and into low-skilled work and vice versa represents an obstacle to interpreting the unemployed as a clear and stable class category, distinct from the low-skilled occupational category. Additionally, classifying the unemployed as an underclass still leaves households with no economically active household members without any classification.

We navigate our way through the issues outlined above by implementing a definition of occupational class that has four broad classifications: unemployed, low skill, medium skill and high skill. The low-skill category comprises the so-called elementary occupations and includes domestic, agricultural and fishery workers. The medium-skill category is defined as clerks, service workers and shop and market, craft and related trades workers, plant and machinery operators and assemblers, while the high-skill category includes legislators, senior officials and managers, professionals, technicians and associated professions. The self-employed are classified based on their occupations, in the same way as regular employees. We convert individual-level occupational skill variables to a household variable by using the highest occupational skill level of any household member to classify households. This approach could be defended via Ceruti's (Citation2013) perspective that individuals' class position could be mediated via the life chances and living standards of those with whom they share a home.

Omissions due to working household members not providing any occupational data or a lack of economically active household members constituted 25% and 14% of the population respectively in the NIDS 2008. Despite these shortcomings, the occupation variable is sufficiently reliable to provide a broad overview of the prevalence of middle-class occupations and its interaction with other variables of interest such as race, age and education.

illustrates that the low-skilled and medium-skilled occupational classes combined represent 32% of all South African households. The low-skilled occupational class represents roughly 10%, the medium-skilled occupational class 21.7% and the two tails of the distribution (the highly skilled and the unemployed) 13% and 16% of the population, respectively. In total about 70% of households have at least one member working. Table 1 also shows that higher skilled occupations are associated with higher income levels and educational attainment. Blacks constitute 91% of the unemployed, 86% of households associated with lower skill occupations, 76% of households with medium-skill occupations and 54% of households with high-skilled occupations.

Table 1: Characteristics of classes when categorised based on occupational skill levels, 2008

4.2 Vulnerability

Goldthorpe & McKnight (Citation2004) find that class is correlated with the risk and uncertainty faced by individuals, mediated via the relationship between secure employment contracts, labour market negotiating power and skill scarcity. Following from this, Lopez-Calva & Ortiz-Juarez (Citation2011a) propose a vulnerability approach to categorising class. According to their perspective, non-poor households that faced considerable risk could plausibly still slide into poverty and were thus not yet middle class. This distinction between vulnerability and security aligns with other important divides, including the separation between financial independence and reliance and a short and longer time horizon, which in turn has associations with savings behaviour and human capital investment decisions.

The vulnerability approach requires panel data to estimate the likelihood of falling into poverty based on a range of variables, including service delivery indicators such as access to running water as well as socio-economic characteristics of the head of the household such as educational attainment, employment status, gender and age. The middle class is defined as non-poor households who have a low probability of falling into poverty but who are still below an affluence threshold. The integration of multiple dimensions of deprivation is a key strength of this approach.

We apply the vulnerability approach by running probit regressions to estimate the likelihood of remaining in poverty or falling into poverty in the second wave of the NIDS 2010, based on the household's 2008 characteristics including the unemployment status of the household head, age of the household head (and its square), education of the household head (and its square), whether the household head is black, whether the household head is female, household size and an asset index.Footnote8 Following Argent et al. (Citation2009), we use per-capita income of R502 as the poverty line. Households are defined as lower class if the probability of becoming non-poor in 2010 is below 10%, vulnerable if the probability is between 10 and 50%, middle class if the probability is between 50 and 90%, and upper class if the probability is above 90%.

We find that 23% of households are very likely to be poor in both 2008 and 2010 and therefore considered to be chronically poor and to belong to the lower class. also shows the strong association between race and class when applying the vulnerability approach. Almost 30% of black South Africans are categorised as lower class, a further 46% belong to the vulnerable class, 24% to the middle class and only 3% are categorised as upper class. In contrast, there are virtually no whites amongst the lower classes and the vulnerable, but 23% of white South Africans are categorised as middle class and 77% as upper class.

Table 2: Characteristics of classes when categorised based on vulnerability approach, 2008

4.3 Income

Income is often used to estimate class because it provides a measure of an individual's economic power and is viewed as a correlate of social status because it determines a household's buying power and reflects market value and negotiating power in the labour market. Because income is a continuous variable, classes are defined using cut-off values of income. In economics, the middle class is often defined as a residual category, distinct from the lower classes (or the poor) and the upper class (or the affluent); two cut-off points are therefore required. Such points are usually defined based on percentiles, median or mean values or, alternatively, absolute thresholds.

Class can be defined using fixed percentages of the income distribution. For instance, Easterly (Citation2001) defines the bottom 20% as lower class and the top 20% as upper class, thus categorising the remaining 60% as the middle class. One can also define poverty and affluence lines respectively as a share and multiple of a mean or median income. Birdsall et al. (Citation2000) define the middle class as those with income between 0.75 and 1.25 of median per-capita income. Alternatively, we can use a poverty line set a specific level of per-capita income as the cut-off point to distinguish the middle class from the poor and, similarly, a line of affluence to distinguish the middle class from the affluent. This approach is sometimes preferred over the relative measures reliant on percentiles and medians because it allows comparisons with other countries.

However, all of these approaches remain vulnerable to the criticism that the imposed thresholds are arbitrary; we therefore opt for a polarisation method developed by Esteban et al. (Citation1999) to find homogeneous social clusters using the underlying concepts of identification and alienation. The authors argue that traditional approaches utilising arbitrary cut-off points often result in groups without any internal cohesion and in which there is considerable variation in characteristics. This is likely to be a risk when applying arbitrary thresholds to South Africa's fragmented and unequal social landscape where there is little evidence of a large cohesive core. Using the patterns in the data to identify clusters and to make decisions about natural breaks and cut-off points, the polarisation method is more responsive to the anomalies and atypical features of South Africa's income distribution. Assuming that income patterns capture and reflect important differences in lifestyle and life chances that will correlate with patterns of socialisation and social identification, such an approach can offer an empirically grounded and defensible avenue to identifying a reasonably homogeneous and cohesive middle class within an unequal and divided society.

As expected, shows large gaps in the mean income per capita of lower-class, middle-class and upper-class households (R376, R1763 and R9573 respectively). The mean educational attainment of the highest skilled individual in the household varies according to class: it is 7.6 years for the lower classes, 9.6 years for the middle class and 12.5 years for the upper class. Both the lower and the middle classes are predominantly black (92% and 70% respectively), but the black share of the upper class is only 29%. One in four blacks is middle class.

Table 3: Characteristics of classes when categorised using the income polarisation approach, 2008

4.4 Self-identification or subjective social class

Perceptions of individual ranking and social standing have long interested sociologists. Theorists such as Marx (Marx & Engels, Citation1968:37; Marx, Citation1972) and Durkheim (Citation1933) assumed that individuals knew their position in society and that there was an alignment between objective and subjective social status. In contrast, the reference-group hypothesis raises the possibility that there may be a divergence between objective and subjective social class. It acknowledges that individuals' perceptions of their place in the social hierarchy are largely formed by their circle of close acquaintances (Stouffer et al., Citation1949). The crux of the argument is that the homogeneity of reference groups – the assortative tendency to surround oneself with friends of similar education, occupation and income – fundamentally distorts the subjective sample from which one generalises to the wider society and from which one develops perceptions of one's subjective location. Taken together, these lead to images of society with few at the top, the great majority in the middle and few at the bottom. In this view, perceptions of the shape of the social stratification system and of one's place in it are only loosely linked to objective circumstances, since objective conditions are filtered through the lens of reference groups.

We examine these theories by investigating self-identified social position using the NIDS data. All adult respondents were asked to imagine a six-step ladder with the poorest people in South Africa on the bottom or first step and the richest people standing on the top or sixth step. Respondents were then asked on which rung of the income ladder they saw their household. While the terms poor and rich would conventionally be interpreted in a narrow sense as referring to income, there is room for broader interpretations, especially given the use of the ladder metaphor.

According to , perceptions of socio-economic position appear to be related to education level and income, but there is no association with age. There appears to be a tendency or desire to occupy a middle position rather than an extreme or outlying position in the social distribution. Assuming that objectively each rung of the ladder represents an equal proportion of the population, we can identify overrepresented categories. The analysis shows that 34% of the population place themselves on the bottom two rungs (33% based on equal share assumption), but a much higher than proportional 59% of the population place themselves on rungs three and four and a very low proportion (8%) see themselves as standing on one of the top two of society's ladder rungs. High social status individuals tend to underestimate their position in society.

Table 4: Characteristics of classes when categorised using self-reported assessment, 2008

Could this be explained by the reference-group hypothesis? In a country marked by deep and overlapping cleavages between white and black, affluent and poor, highly educated and low skilled, suburbs and townships, the reference-group hypothesis would lead a greater share of South Africans to identify themselves as standing on the middle rung of society's ladder when they are in fact at the top or the bottom. However, if race continues to serve as a good approximation for these overlapping social divides fostered by apartheid, then it is important to consider the distribution of self-identified social rank separately for black and white South Africans. For the black population, a slightly lower than proportional share views themselves as standing on the middle two rungs of the ladder (56%) and a slightly higher proportion on the lower two ladder rungs (38%) or the top two rungs (6%). Similarly, for the white population a much smaller proportion places themselves at the bottom of the distribution (13%), while 74% see themselves on the middle two ladder rungs and only 13% think that they occupy the top two rungs of society. This shows that both black and white South Africans of high social standing tend to underestimate their position in society. This is in line with Phadi & Ceruti's (Citation2011) research, which showed that residents of Soweto preferred to see themselves as positioned in the middle of the social distribution, buffered from both sides by a more privileged and less privileged group.

While this analysis from the NIDS provides an interesting perspective on perceived social standing, it does not engage directly with the literature on self-assessed or subjective class. Consequently, we also consider self-identified class based on the WVS of 1995, 2001, 2006 and 2013. shows that the majority of South Africans consider themselves to be lower or working class. Those who identify themselves as middle class (including both the lower or upper middle class categories) grew from 32% in 1995 to 40% in 2001 before dropping to 35% in 2006 and 29% in 2013. A small minority of respondents consider themselves to be upper class in contemporary South Africa.

Table 5: Self-reported social class in South Africa, 1995, 2001, 2006 and 2013

According to the 2006 WVS, those who identify themselves as lower class appears to be a distinct group with lower education and income levels. This group is also almost entirely black (97%). The distinction between those who identify themselves as working class or lower middle class appears to be more subtle, with similar age profiles, income levels, educational attainment and racial shares. The lines between upper middle class and upper class are also blurred with similar educational attainment, but with a slightly lower income level, lower age and higher black share for the upper class.

This work confirms earlier results by Seekings (Citation2007) for a small sample of Cape Town residents showing that neighbourhood characteristics, race and occupation can only explain a modest share of the overall variation in subjective self-reported class. He concludes that ‘the relationship between subjective and objective class was not tidy’ (2007:30).

4.5 Comparing cross-section estimates with rival approaches

Viewing the vulnerability, occupation and income approaches as approximations of objective social status, we examined the misalignment between subjective and objective social status in more depth. When using the vulnerability approach to define classes, white South Africans are absent from the lower classes and there is only a negligible share of blacks who are classified as upper class. The individual-level data on self-reported social standing in the NIDS showed that there was a greater tendency to underestimate social standing amongst blacks (controlling for occupation, household income and education via regression analysis). This is in line with the qualitative work of Khunou (Citation2012) and Krige (Citation2012) suggesting that some young, educated and affluent black South Africans describe their membership of the middle class as tentative and conditional. The reluctance to use the middle-class label could be attributed to the term's strong historical association with being white. Alternatively, this evidence of greater vulnerability may link to Nieftagodien & Van der Berg's (Citation2007) conclusion that the black middle class has a substantial asset deficit compared with other members of the middle class (Burger et al., Citation2014).

We use the 2006 WVS to analyse the correlates of self-identified class. Using regression analysis to examine the relationship of self-identified class and a list of characteristics that theory suggests should be linked to class (including a living standards index, education and occupation), it appears that the traditional, so-called ‘objective’ dimensions of class can explain only a small share of how individuals self-identify into classes. Our analysis suggests that a multi-dimensional living standards index has the most powerful association with self-identified class and explains about 22% of the observed variation in self-identified class. Years of education is also significant, but only explains 8% of the observed variation in self-reported class. Occupations and the manual-cognitive content of work both have a significant association with self-reported class, but do not explain much of the variation.

Similar to the findings of Lopez-Calva et al. (Citation2011b), we find little empirical basis for the widely held belief that certain values and attitudes are robustly and significantly associated with the middle class. This also resonates with the findings of Mattes (Citationforthcoming), which show virtually no significant relationship between middle-class membershipFootnote9 and patriotic or democratic values. Independence, financial prudence and imagination were significantly associated with the likelihood of respondents classifying themselves as middle class, but these values did not contribute much in terms of explanatory power nor was there a significant association between these values and the likelihood of identifying as middle class amongst the black sample. The only noteworthy exception to this rule is our finding that black South Africans who regard religion as important are significantly more likely to describe themselves as middle class.

5. Comparing trends in the middle class for rival approaches

We compare trends in the growth of the black middle class applying our four approaches to three waves of the NIDS and the 1993 PSLSD. We also examine self-reported class according to the WVS in 1995, 2006 and 2013.

Unfortunately, the 1993 PSLSD has a large number of missing values for occupation and we were thus forced to exclude this occupation class estimate for this survey. To ensure the comparability of estimates of the middle class, we had to implement a simplified version of the vulnerability modelFootnote10 using a linear probability model instead of a probit. We implement the income approach by adjusting the cut-off points estimated in the 2008 NIDS for inflation.

Based on occupation there has been only a modest increase in South Africa's black middle class share between 2008 and 2012; it increased slightly from 35% in 2008 to 37% in 2012. Because we do not have estimates for 1993 for occupational class and because the estimated trend is very flat for the rest of the years, we do not include these numbers in the figure.

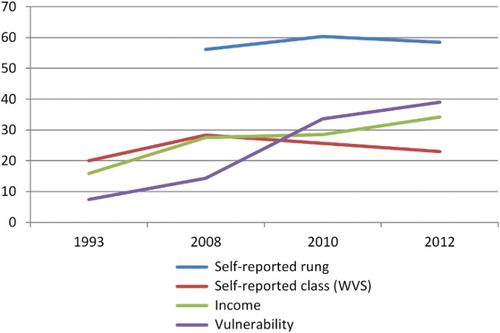

Figure 1: Comparing trends in rival approaches for 1993, 2008, 2010 and 2012 (or closest years)

shows a dramatic increase in the proportion of black South Africans classified as middle class based on both the income and the vulnerability approach, but with a more pronounced rise in the black middle class according to the vulnerability approach than when using an income measure. The steep rise in the black middle class shown by the vulnerability approach (from 7.4% in 1993 to 39.0% in 2012) may be partly due to improvements in the circumstances and characteristics associated with greater financial security such as educational attainment, access to clean water and electricity and ownership of stoves and fridges. When class is measured based on per-capita household income cut-off points (as described in Section 4.3), the increase in the black middle class is less pronounced than in the case of the vulnerability approach, but the rise remains sharp from 15.9% in 1993 to 34.2% in 2012.

It is illuminating to compare these more ‘objective’ indicators with trends in how individuals described their own social position. As reported before, we find that individuals overwhelmingly tend to place themselves in the middle of the income distribution, with about 60% of respondents identifying themselves to be on the middle two rungs of the income distribution. Although one should be cautious to compare the NIDS estimates with those from the WVS, the magnitude of the gap is wide enough that it is not controversial to observe that many South Africans who think of themselves as being in the middle of the income distribution do not describe themselves as middle class, indicating that this is a more loaded term and is not simply seen as referring to those who see themselves occupying the middle of the income distribution.

Because the self-reported rung question is based on a relative classification of social position and income, one would not expect it to be responsive to absolute improvements in income or security. However, one may expect some correspondence between the self-reported class and our ‘objective’ class indices such as the vulnerability approach and the income measures. It is therefore interesting to see that the sharp observed rise in the black middle class shown by these ‘objective’ indicators is not mirrored in the proportion of black South Africans who classify themselves as middle class over this period. This is in line with previous studies showing that individual conceptions of what class membership means are slow to change, but more significantly that there is a sluggish response of identity to changes in the individual's ‘class markers'. This could be related to an inherent reluctance to reclassify oneself, especially in a context where class has a strong link to social identity or may confirm Inglehart & Welzel's (Citation2005) ideas around the socialisation aspect of class and the dominant role of childhood experiences and circumstances.

6. Conclusion

Our analysis shows considerable variation in who is classified as middle class based on the different definitions that we employ. While there is some overlap, there are also substantial differences in who is identified as the middle class based on whether we implement the occupational, income, vulnerability or subjective social status approach to discern class membership. Reported income, occupation and vulnerability measures appear to have a weak relationship with self-identified class. This is in line with the work of Schlemmer (Citation2005), who argued that the South African middle class lacks cohesion and that skilled and affluent individuals are reluctant to self-identify as middle class. Qualitative work by Khunou (Citation2012) and Krige (Citation2012) suggests that well-educated, skilled black South Africans appear uncomfortable with the ‘middle class' tag and are hesitant to describe themselves in this way – seemingly at least partly because of the category's strong historical association with being white and consequent perceived tensions between their racial and cultural identity and persistent ideas around what being ‘middle class' represents.

The country's apartheid past, and the post-apartheid state's responses to this, obviously strongly influenced both the nature of the middle class in contemporary South Africa and individual behaviour of members of this class. The perceived vulnerability of sections of the black middle class has much to do with the fact that they lack the assets that allow them to fully adopt a middle-class lifestyle, but also with the tenuousness of their middle-class status. Stronger economic growth would perhaps have engendered greater confidence in their ability to maintain their status, but modest economic growth over most of the post-transition period and economic shocks may have undermined greater security.

State policies greatly influenced the growth and the nature of the black middle class. Economic empowerment created a small but visible group of black capitalists. More important in numerical terms was upward social mobility in both the public and private sectors, with affirmative action policies lending support. The beneficiaries were those best placed to enter the higher rungs of the labour market. The immediate post-apartheid period and some catch-up allowed a large expansion of this group, but the weak performance of both the education system and the economy does not augur well for similarly rapid expansion in future. This creates an interesting political dynamic, with younger cohorts expecting more well-remunerated jobs than the education system and labour market may be able to provide.

Social identity is a crucial factor in the pursuit of greater social cohesion and political stability. If the racial gap in earnings and education is decreasing, but racial differences continue to loom large in the minds of South Africans, the growth in the black share of middle-class professions or the black share of income may not translate to a more integrated and less polarised social and political landscape. This may also be an important finding for the wider literature, demonstrating that it is vital to move beyond the surface and explore how class categories are perceived and used. Research on class should consider not only objective social status, but also subjective social status – especially in light of its potential role in mediating key economic and political benefits associated with the middle class.

Funding

This work was supported by the Vice-rector of Stellenbosch University's discretionary fund.

Notes

5For instance, Pakulski (Citation2005) argues that the complex configurations of classless inequality and antagonism call for more comprehensive theoretical and analytic constructs.

6The survey includes approximately 9000 households.

7Seekings & Nattrass (Citation2005) point out that there can be variation in the labour market prospects among the unemployed, including, for instance, skilled individuals from affluent households using unemployment as a waiting bay for the right opportunity. However, less than 1% of those who were unemployed in 2008 earned R10 000 or more in wages (measured in 2008 SA Rands) in the two consecutive waves of NIDS (2010, 2012).

8The asset index is estimated using the multiple correspondence analysis command in Stata, based on variables relating to various aspects of the household's living conditions including access to water and sanitation and the energy sources used for lighting, heating and cooking, access to credit, home ownership and a long list of household possessions. The list of household possessions include car ownership and owning a television, microwave, radio, satellite, VCR, computer, camera, electric stove, gas stove, microwave, fridge, washing machine, sewing machine, knitting machine, lounge suite, motorcycle, plough, tractor, wheelbarrow and grinding mill.

9Mattes defines the middle class as individuals ‘whose salaries and social milieu enable them to live middle class lifestyles' (Citationforthcoming) and who are never without the basic necessities (e.g. water, food, healthcare).

10Here we use a more parsimonious asset index (cf. model in Section 4.2) because we are restricted to assets that occur both in the 1993 PSLSD and the NIDS panel. We implement asset terciles using access to clean water, adequate sanitation, electricity, fridge, television or radio and stove.

References

- Argent, J, Finn, A, Leibbrant, M & Woolard, I, 2009. Poverty: Analysis of the NIDS Wave 1 dataset. NIDS Discussion Paper No. 13, South African Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU), School of Economics, University of Cape Town.

- Beckett, A, 2010. Is the British middle class an endangered species? The Guardian, 24 July, p. 28. http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/jul/24/middle-class-in-decline-society Accessed 2 July 2013.

- Birdsall, N, 2010. The (indispensable) middle class in developing countries; Or, the rich and the rest, not the poor and the rest. Working Paper 207, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, USA.

- Birdsall, N, Graham, C & Pettinato, S, 2000. Stuck in the tunnel: Is globalization muddling the middle class. Working Paper No 14, Center on Social and Economic Dynamics, Washington, DC, USA.

- Burger, R, Louw, M, Pegado, B & Van Der Berg, S, 2014. Understanding the consumption patterns of the established and emerging South African black middle class. Development Southern Africa 32(1). doi:10.1080/0376835X.2014.976855

- Ceruti, C, 2013. A proletarian township: Work, home and class. In Alexander, P, Ceruti, P, Motseke, K, Phadi, M & Wale, K, Class in Soweto. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Scottsville.

- Crankshaw, O, 1997. Race, Class and the Changing Division of Labour Under Apartheid. LSE, London.

- Durkheim, E, 1933. The Division of Labour in Society. Free Press, Glencoe.

- Easterly, W, 2001. The middle class consensus and economic development. Journal of Economic Growth 6, 317–35. doi: 10.1023/A:1012786330095

- Esteban, J & Ray, D, 1994. On the measurement of polarization. Econometrica 62(4), 819–52. doi: 10.2307/2951734

- Esteban, J, Gradín, C & Ray, D, 1999. Extensions of the measure of Polarization, with an application to the income distribution of five OECD countries. Working Paper No. 218, Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, New York.

- Evans, G & Mills, C, 1999. Are there classes in post-communist societies? A new approach to identifying class structure. Sociology 33(1), 23–46.

- Glassman, RM, Swatos, WH & Kivisko, P, 1993. The Noble Character and Flaws of the Middle Class. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport, CT.

- Goldthorpe, JH, 1987. Social Mobility and Class Structure in Modern Britain. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Goldthorpe, JH & Erikson, R, 1993. The Constant Flux. A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Societies. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Goldthorpe, JH & McKnight, A, 2004. The economic basis of social class. CASE Paper 80, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics and Political Science, London.

- Inglehart, R & Welzel, C, 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Khunou, G, 2014. What middle class? The shifting and dynamic nature of class position. Development Southern Africa 32(1).

- Krige, D, 2014. ‘Growing up’ and ‘moving up’: Metaphors that legitimise upward social mobility in Soweto. Development Southern Africa 32(1).

- Lopez-Calva, LF & Ortiz-Juarez, E, 2011a. A vulnerability approach to the definition of the middle class. Policy Research Working Paper Series 5902, The World Bank, Washington, DC, USA.

- Lopez-Calva, LF, Rigolini, J & Torche, F, 2011b. Is there such thing as middle class values? Class differences, values and political orientations in Latin America. Policy Research Working Paper 5874, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Mattes, R. Forthcoming. South Africa's emerging black middle class? Journal of International Development.

- Marx, K. 1867. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Charles H. Kerr and Co., Chicago.

- Marx, K, 1972. Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844: Selections. In Tucker, RC (Ed.), The Marx-Engels Reader. W.W. Norton, New York.

- Marx, K & Engels, FC, 1968. The Communist Manifesto. International Publishers, New York.

- Nieftagodien, S & Van der Berg, S, 2007. Consumption patterns and the black middle class: The role of assets. Stellenbosch Economic Working Paper 02/07, Bureau for Economic Research & Department of Economics, University of Stellenbosch.

- Pakulski, J, 2005. Foundations of a post-class analysis. In Wright, EO, Conclusion: If Class is the Answer What is the Question. Approaches to Class Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Phadi, M & Ceruti, C, 2011. Multiple meanings of the middle class in Soweto, South Africa. African Sociology Review 15(1), 88–108.

- Rivero, C, Du Toit, P & Kotze, H, 2003. Tracking the development of the middle class in democratic South Africa. Politeia 22(3), 6–29.

- Schlemmer, L, 2005. Lost in transformation? South Africa's emerging middle class. CDE Focus Occasional Paper No 8, Centre for Development and Enterprise, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Seekings, J, 2003. Do South Africa's unemployed constitute an underclass? Working Paper No. 32, Centre for Social Science Research, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Seekings, J, 2007. Perceptions of class and income in post-apartheid Cape Town. CSSR Working Paper No. 198, Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town.

- Seekings, J, 2009. The rise and fall of the Weberian analysis of class in South Africa between 1949 and the early 1970s. Journal of Southern African Studies 35(4), 865–81. doi: 10.1080/03057070903313228

- Seekings, J & Nattrass, N, 2005. Race, Class and Inequality in South Africa. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

- StatsSA (Statistics South Africa), 2009. Profiling South Africa middle class households, 1998–2006. Statistics South Africa Report 03-03-01, Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Stouffer, SA, Suchman, EA, de Vinney, LC, Star, SA & Williams, JR, 1949. The American Soldier: Adjustment during Army Life. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Van der Berg, S. 2010. The demographic and spatial distribution of inequality. In Bernstein, A (Ed.), Poverty and Inequality: Facts, Trends and Hard Choices. Centre for Development and Enterprise Round Table Paper Number 15, Centre for Development and Enterprise, Johannesburg.

- Visagie, J & Posel, D, 2013. A reconsideration of what and who is middle class in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 30(2), 149–67. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.797224

- Weber, M, 1961. Essays in Sociology. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

- Weber, M, 1968. Economy and society: An outline of Interpretive Sociology. Bedminster Press, New York.

- Wright, EO, 1979. Class, Crisis and the State. Verso, London.

- Wright, EO, 1980. Class and occupation. Theory and Society 9, 177–214.

- Wright, EO, 1989. The Debate on Classes. Verso, London.