Abstract

Children in Zimbabwe suffered badly during the long crisis from circa 1990 to 2008 as the economy and social services collapsed, under-five mortality, maternal mortality and malnutrition rose, the number of orphans increased 20-fold and thousands of children experienced psychosocial trauma. Recent household surveys in Zimbabwe show that most indicators of child welfare remain at or below where they were 25 years ago. Many effects of the crisis on children are long term, even permanent, including prenatal and early childhood malnutrition, orphanhood, traumas from witnessing or being victims of violence, and disrupted education. This article analyses the Government of Zimbabwe's two most recent national development plans in relation to children's needs and rights as expressed in major international declarations. Suggestions are made for focusing on re-establishing basic services to break the cycle of harm to children, build children's capacities and deal with past traumas.

1. Introduction

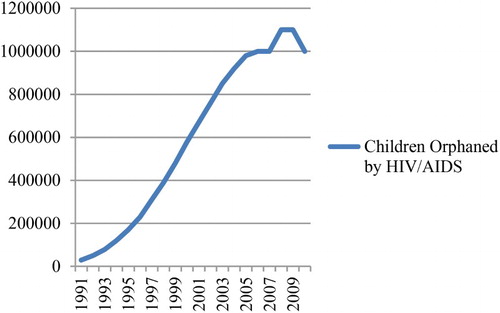

Children suffered badly during the long crisis in Zimbabwe from circa 1990 to 2008. The first decade after Independence in 1980 saw important improvements in the lives of children, especially in health and education (UNICEF, Citation1994; Chimhowu et al., Citation2010). Beginning in the late 1980s, however, social indicators began to deteriorate; average life expectancy started to decline and under-five mortality began to rise between 1988 and 1990 (CSO, Citation1994). Initially, the culprit was HIV/AIDS, whose importance was widely underestimated. Over the next 15 years, the number of children orphaned due to HIV/AIDS rose 20-fold (World Bank, Citation2014). A growing fiscal crisis, which hampered the government's ability to deliver services for children, aggravated the impacts of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The government ran a fiscal deficit for over 30 consecutive years until 2008 (Comptroller and Auditor General, Citation1974/75–present), leading to increasing government debt, crowding out of private investment, money creation and inflation (Mumbengegwi, Citation2002). The severe droughts of 1992 and 1995, on top of a botched structural adjustment programme, led to a generalised increase in poverty in the 1990s (CSO, Citation1998; Chimhowu et al., Citation2010). Poverty rates increased in the 2000s as gross domestic product per capita fell by 50% between 1998 and 2008 (World Bank, Citation2014). The year 2000 saw invasions of commercial farms, rejection of the constitutional referendum and electoral violence. The country was by then in crisis, economically, socially, politically and epidemiologically. At the nadir from 1999 to 2008, Zimbabwe's under-five mortality rate (U5MR) was similar to that in countries experiencing protracted civil strife such as Afghanistan, Haiti, Sudan and Timor Leste (World Bank, Citation2014). Average life expectancy in Zimbabwe fell to 43 years in 2003, one of the 10 lowest on earth at that time (World Bank, Citation2014).

Economic and political conditions stabilised in 2009 and the economy began to grow again, albeit slowly and unevenly. The introduction of the multi-currency system in 2009 ended the hyperinflation and allowed the government to regain control of the fiscus. The 2009–13 Coalition Government brought relative peace and stability. Together, these measures facilitated the resumption of many basic services for children. The central hospitals and universities, along with most health clinics and schools, resumed operations, although often hampered by shortages of staff, equipment and supplies (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2011). Since they are now paid a living wage, teachers, health workers and other civil servants now show up to work more regularly than they did during the crisis years (Chagonda, Citation2012). Despite some improvements since 2009, however, both economic growth and the government's fiscal position have faltered somewhat since 2012. Civil service salaries sometimes go unpaid; suppliers to the government complain of late payments.

Despite the resumption of many social services since 2009, many social indicators in Zimbabwe are comparable with what they were 20 to 25 years ago. Furthermore, many effects of the long crisis on children, such as elevated levels of pre-natal and chronic malnutrition, high rates of orphanhood, psychological trauma and disrupted education, will have long-term impacts. In light of these facts, this paper asks what might be appropriate and feasible policies for Zimbabwe's children in the post-crisis era.

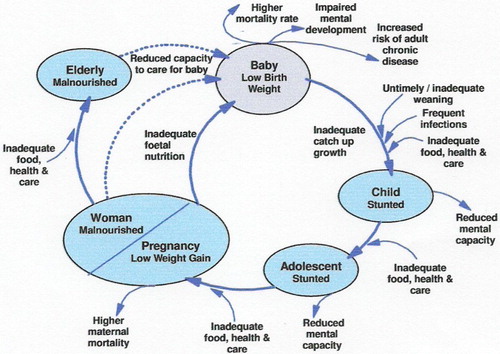

This article investigates the situation of children in Zimbabwe using the measure of child rights and welfare contained in the major international declarations and conventions on child welfare and child rights: the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (UN, Citation1989), the declaration of the UN Special Session on Children (UN, Citation2002) and the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), especially those related to children: MDG1 (eliminate extreme poverty and hunger), MDG2 (achieve universal primary education), MDG4 (reduce child mortality), MDG5 (improve maternal health) and MDG6 (combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases). The Government of Zimbabwe has repeatedly committed itself to these international frameworks (Republic of Zimbabwe Citation2000; Government of Zimbabwe Citation2004; Zimbabwe & United Nations, Citation2010, Citation2012). This article thus focuses on the main internationally used and recognised indicators of maternal and child welfare in Zimbabwe, such as the U5MR, infant mortality rate (IMR), maternal mortality rate (MMR), HIV/AIDS prevalence, child malnutrition (both as part of MDG1 and as a driver of MDG2 and MDG4), primary school enrolment, rates of orphanhood, and access to basic social services such as immunisation. provides a schematic illustration integrating the concepts of maternal and child health, nutrition and welfare.

Figure 1: Links between maternal and child health, nutrition and welfare

The article draws on the World DataBank and six methodologically comparable nationwide household surveys (CSO & Institute for Resource Development/Macro Systems, Citation1989; CSO & Macro International, Citation1995, Citation2000, Citation2007; Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) & UNICEF, Citation2010; ZIMSTAT & Measure Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), IFC Macro, Citation2012).Footnote2

The article first outlines the medical, psychological, nutritional, educational and socio-economic effects of long-term socio-economic crisis on children and summarises the situation of children in Zimbabwe since the 1980s; the expected effects of socio-economic crisis on children have indeed manifested themselves in Zimbabwe over the past 25 years. The article then analyses the Government of Zimbabwe's responses to the situation of children in Zimbabwe as outlined in the last two national development plans: the Zimbabwe Medium Term Plan 2011–15 (MTP) (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2011) produced by the Coalition Government; and its replacement, the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation (ZimASSET) (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013), produced by the ZANU(PF) Government elected in 2013. Suggestions are made for focusing on re-establishing basic services, with emphasis on building quality, equity and coverage, and a strategy of breaking the cycle of harm to children, building children's capacities and dealing with past traumas.

2. Effects of socio-economic crisis on children and the situation of children in Zimbabwe, 1980–2013

Long-term economic decline reduces the resources that parents, families and communities have to provide for their children. It also means fewer resources for the health, education and child protection services run by government, leading to falls in service quality, coverage and equity. Given their psychological immaturity and their social and legal status as minors, children are less able to advocate for their own interests when policy affecting children is made. When civil discourse breaks down, children's voices are even less likely to be heard. Violent conflict and epidemic disease break down the social structures that support and care for children (UNICEF, Citation1996).

In extreme crisis, more children die of acute malnutrition, epidemic disease and neglect. These factors often interact in a vicious cycle. The most common effects of crisis include increased prevalence of chronic malnutrition, decreased school enrolments and higher rates of school absenteeism, higher rates of disability and higher levels of child abuse and neglect. These effects often last generations () (UNICEF, Citation1996, Citation1998).

Malnutrition in the first three years of life can irreversibly affect both the child's physical and mental development (UNICEF, Citation1998, Citation2009). Malnutrition-induced decreases in cognitive functioning lead to poorer educational outcomes once the child enrols in school and to poorer career prospects later in life. Severe malnutrition amongst pregnant women is doubly damaging: to the woman and her unborn child (UNICEF, Citation2007, Citation2009). Such pre-natal malnutrition leads to increased rates of low birth weight. Children of low birth weight suffer higher IMR, are more prone to infection, are slow to develop physically and frequently show impaired cognitive development (UNICEF, Citation1998). Severe pre-natal malnutrition leads to increased rates of mental illness in adults (Neugebauer, Citation2005).

Socio-economic crisis affects the coverage and quality of formal education. Parents are less able to afford school supplies and uniforms. As government funding decreases, textbooks and chalk become scarce. Teachers become demotivated as inflation erodes theirs salaries, and sometimes they are not paid at all (Chagonda, Citation2012). Social and political conflict may lead to schools closing. The decline in the quality and quantity of schooling leads to lower levels of literacy, numeracy and life skills; these in turn have impacts on individuals’ prospects for employment and social mobility in later life (UNICEF, Citation1996, Citation1999). Once generalised, these phenomena can affect a whole generation of children. New forms of age- and class-based social cleavage may emerge, as the children of the privileged, mostly urban, classes ride out the storm while the worst affected children, usually rural, see their education disrupted the most (Bell & Huebler, Citation2011; Sadomba, Citation2011).

Lower rates of school enrolment interact inter-generationally with health, nutrition and childcare variables. Women with less education have higher risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections including HIV, are less likely to take their children for appropriate medical care when it is needed, and their children face a higher U5MR (UNICEF, Citation2007; ZIMSTAT & UNICEF, Citation2010).

Crisis situations produce increases in political and domestic violence, criminality, political polarisation and breakdowns in levels of trust. Children may be traumatised by witnessing violence, by being victims or by being recruited to commit violence, often with long-term physical and psychological effects (UNICEF, Citation1996).

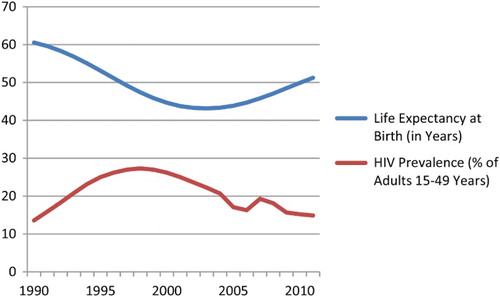

So to what extent did Zimbabwe's children experience such negative effects of crisis? Zimbabwe's resource base did indeed shrink; gross domestic product per capita (measured in constant 2000 US$) peaked at US$574 in 1998; it then fell for 10 consecutive years, to US$284 in 2008 (World Bank, Citation2014). The hyperinflation of the 2000s eroded the salaries of teachers and health workers, leading many to emigrate, leave the civil service or simply not show up at work; many schools, health facilities and government offices closed for lack of staff, equipment and supplies (UNICEF et al., Citation2011; Chagonda, Citation2012). Health and other social indicators collapsed. Average life expectancy (which includes the U5MR but is also indicative of broader social, economic and epidemiological issues affecting adults) declined for over 15 years straight. The changes in average life expectancy in Zimbabwe were largely driven by the HIV/AIDS epidemic ().

Figure 2: Average life expectancy and HIV prevalence, Zimbabwe, 1990–2011

Note: For average life expectancy, the scale on the y axis is in years; for HIV prevalence, the y-axis scale is in per cent.

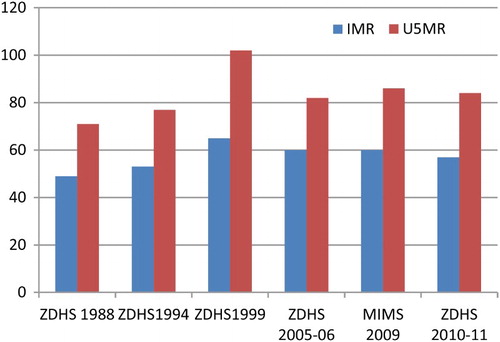

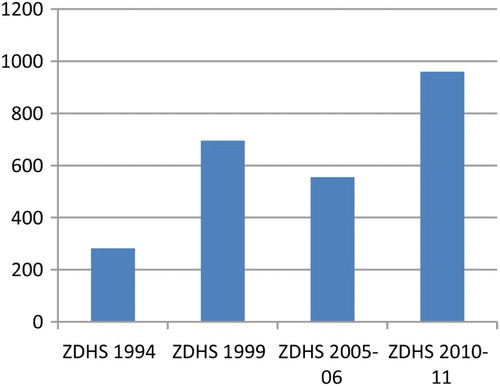

Zimbabwe's IMR and U5MR rose during the crisis. Zimbabwe saw its lowest mortality rates in the late 1980s and its highest mortality rates in the early 2000s. The U5MR has not decreased significantly since 2005/06 (); both the IMR and U5MR remain above their pre-crisis levels. Even more worrisome, the MMR stood at an all-time high in 2011 (), although it is not clear why. We are thus faced with the paradox that childhood mortality remains high and maternal mortality is rising, while overall life expectancy appears to be rising. The abating of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is certainly responsible for much of the rise in life expectancy (since adult mortality is declining), while other factors may be keeping the IMR, U5MR and MMR at historically high levels.

Figure 3: Infant and under-five mortality rates, Zimbabwe, 1984–2011

Note: Each survey measures the IMR and U5MR for the four years prior to that survey; for example, the ZDHS1988 measures the IMR and U5MR for the period 1984–88. ZDHS, Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey; MIMS, Multiple Indicator Monitoring Survey.

Figure 4: Maternal mortality rate, Zimbabwe, 1994–2011

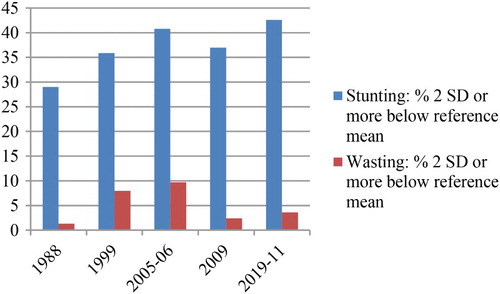

Children's nutritional status also deteriorated during the crisis. Chronic malnutrition rates today remain above pre-crisis levels (). Low weight for height, or wasting, is evidence of acute malnutrition, the result of severe recent shortage of food, often compounded by disease. Wasting increased sevenfold during the crisis years, although it has decreased in recent years. However, low height for age, or stunting, reached record highs in 2010/11. Stunting is evidence of chronic malnutrition, associated with inadequate food intake over long periods and/or a high burden of disease. The high levels of stunting may explain the stubbornly high IMR and U5MR in Zimbabwe in the last five years.Footnote3

Figure 5: Stunting and wasting among children 12–59 months, Zimbabwe, 1988–2011

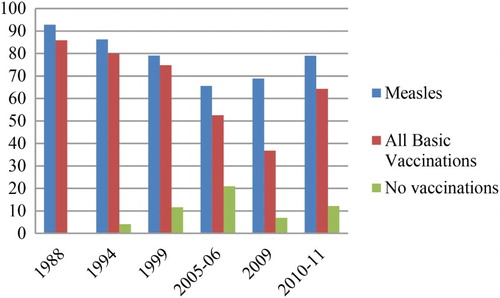

The quality and accessibility of health services are also important to children. While quality and accessibility are harder to measure than mortality or malnutrition, good proxies exist, such as immunisation rates, which indicate how well the health system reaches children with basic services. Immunisation coverage fell from the late 1980s to the late 2000s, recovering only very recently. The fall in the proportion of fully immunised children from 86% in 1988 to less than 40% in 2009 is proof of how badly the crisis affected the health care system. The proportion of children getting no immunisation is still over 10% ().

Figure 6: Immunisation rates for children 12–59 months, 1988–2011

Note: In 1988, no ZDHS data were published on the percentage of children with no immunisation. ZDHS – Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey.

Driven by the HIV/AIDS epidemic amongst the adult population, the numbers of orphans in Zimbabwe soared during the long crisis (), peaking in 2008/09 at almost one-quarter of Zimbabwean children (ZIMSTAT & UNICEF, Citation2010:137). Such extraordinary levels of orphanhood create severe social and psychological disorders, especially when, as in Zimbabwe, the orphan crisis coincides with economic collapse, the deterioration of social services and often violent political conflict.

Figure 7: Number of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS, Zimbabwe, 1990–2010

Note: An orphan is a child zero to 17 years of age who has lost one or both parents due to HIV/AIDS.

In 2000, Zimbabwean orphans were 15% less likely to be in school than other children (World Bank, Citation2014); in 2009, they were 10% less likely to attend school (ZIMSTAT & UNICEF, Citation2010:136). Orphans also suffered higher rates of stunting than other children (42% vs. 35%) in 2009 (ZIMSTAT & UNICEF, Citation2010:141). Orphans are likely to receive less psycho-social and health care and are less likely to be socialised according to appropriate cultural norms than other children. In 2009, only 21% of orphans received any of the six forms of social, material, educational, medical or emotional and psychosocial care to which they were entitled; only 4% had received any emotional and psychosocial support in the previous three months (ZIMSTAT & UNICEF Citation2010:143 and 292). These rates were slightly worse than they had been in 2005/06: 31% and 6% (CSO & Macro International Citation2007:296). Orphaned children are more vulnerable to abuse and neglect and are at higher risk of early sexual activity (CSO & Macro International Citation2007:292–3). Because orphanhood in Zimbabwe is driven overwhelmingly by HIV/AIDS, orphans often live in households where one or more adults are sick, possibly dying; such parents are less able to look after their children. In 2005/06, Zimbabwean orphans were less likely to have a pair of shoes, two sets of clothes and a blanket than other children; only 52% of orphans had all three, while 66% of non-orphans did (CSO & Macro International Citation2007:290). Adult caregivers of orphaned children are more prone to clinical depression than caregivers of non-orphaned children (Kuo et al., Citation2012).

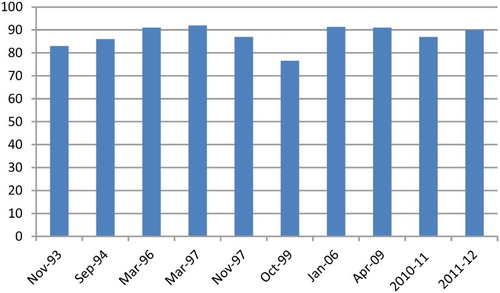

In the first decade after Independence, the rapid expansion of educational opportunities for the black majority was a great source of pride for Zimbabwe (UNICEF, Citation1994; Chimhowu et al., Citation2010: 69–75). The net primary school enrolment rate (i.e. the percentage of six to 12 year olds enrolled in school) was high and fairly stable for many years (). Net enrolment rates have now returned to the 1990s levels.

But enrolment rates are only part of the story. The economic and political crisis of 1999–2008 pushed many teachers to leave the country, and many of those who stayed in Zimbabwe ceased teaching and entered the informal sector (Chagonda, Citation2012). Furthermore, many schools were closed or non-functional for extended periods in the 2000s (UNICEF, Citation2011; Chagonda, Citation2012). Since 2009, the dollarisation of the economy has allowed the government to resume paying public service salaries, at least more regularly than it did during the hyperinflation of 2006–08, and so many teachers have returned to their schools (Chagonda, Citation2012). Still, ‘an estimated 25% of teachers do not meet the minimum teaching qualification requirements’ (UNICEF-Zimbabwe, Citation2011:3).

Even back in 2000, many rural schools in particular lacked physical equipment, supplies, textbooks and trained teachers (Chimhowu et al., Citation2010:70). In its report to the World Education Forum in 2000, the government admitted that real funding per pupil was one-third less than it had been in 1990 and that, with almost 95% of the Ministry of Education's budget going to salaries, the funding available for ‘other educational services such as alternative methods of instruction and other teacher-support systems’ was inadequate (MESC, Citation2000:section 5.1; see also Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2000:9). The government has recently reported that there were three pupils for every English textbook in Zimbabwe's primary schools, and six pupils for every mathematics textbook.

With sporadic attendance by teachers, many of whom are poorly trained, and with inadequate pedagogical materials, it is no surprise that schools are producing poor educational outcomes in Zimbabwe, and that these outcomes have got worse in recent years. Primary school completion rates fell from 82.6% in 1996 to 68.2% in 2006; the pass rate in the Grade 7 (primary school leaving) examination fell to 40% in 2009 (UNICEF-Zimbabwe, Citation2011).

Finally, the high levels of violence during the crisis have resulted in physical and psychological traumas to thousands of Zimbabwean children. Some children have been the direct victims of violence. Many more children have witnessed acts of violence; many children have temporarily or permanently lost a close family member to the violence. Tens of thousands of children had their homes destroyed during Operations Murambatsvina and Garikai in 2005 (International Crisis Group, Citation2006). All children have been affected by growing up in a society with decreased levels of social trust and increased criminality. A few children have been recruited into criminal gangs and violent political groups and have themselves committed acts of violence (UNICEF et al., Citation2011).

In short, Zimbabwe faces a stubbornly high IMR and U5MR, a record high MMR, high rates of chronic malnutrition, poor education outcomes and high levels of psychosocial trauma and social disruption. Despite the relative political and economic stability that the country has achieved since 2009, Zimbabwe's children continue to suffer from the long-term effects of the long crisis.

3. Policy issues

So what is to be done? The analysis in this article follows the principles in the CRC (UN, Citation1989) and the declaration of the Special Session of the UN General Assembly on Children (UN, Citation2002). Specifically, these principles demand that the state should act ‘in the best interests of the child’ (UN, Citation1989), that children should be protected from ‘harm and exploitation’, that ‘every child … must have access to and complete primary education that is free, compulsory and of good quality’, and that ‘the survival, protection, growth and development (of children) in good health and with proper nutrition are the essential foundation of human development' (UN, Citation2002:3). Hence, public policy towards children should aim to ‘break the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition and poor health’, illiteracy and trauma (UN, Citation2002:12). International human rights instruments (e.g. UN, Citation1989:2) allow for the ‘progressive realisation’ of these rights, given the economic and other resources available. In practical terms, this means preventing further harm to children, building children's capabilities (Sen, Citation1999) and dealing with past traumas.Footnote4

This article will now compare the sort of policy prescriptions that these internationally accepted principles suggest with what the Government of Zimbabwe proposed to do in its two recent national development plans, the MTP (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2011) produced by the MDC-ZANU(PF) Coalition Government, and its replacement, ZimASSET (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013), produced by the ZANU(PF) Government after its election victory in July 2013.

3.1 Preventing further harm to children

First, it is important to prevent further harm to children. Preventing further harm implies the re-establishment of basic social services for children throughout Zimbabwe: health, education and social protection. The aim should first be to stop the most easily preventable harms from occurring. Such harms include pre-natal and early childhood malnutrition; preventable early death; preventable illness, especially diseases and conditions likely to have long-term consequences; lack of education; violence and associated psychosocial trauma; and extreme poverty.

The health care system, especially primary health care, has an important role in preventing early death and lifelong disability in children. Primary health care involves heavy reliance on high-impact and cost-effective interventions such as immunisation (including new vaccines against hepatitis, rotavirus and meningitis), micronutrient supplementation (especially vitamin A, iodine and zinc), oral rehydration therapy, provision of essential drugs and the correct case management of the most common childhood diseases and conditions in Zimbabwe (respiratory infections, chronic malnutrition, diarrhoea, HIV and malaria) (UNICEF, Citation1998, Citation2008, Citation2009). Prevention is cheaper than cure, and often brings life-long benefits, for example, when iodine supplementation prevents cretinism. Such preventive measures are also relatively easy to implement, have high impact, have high benefit–cost ratios and respond to public goods and externality problems (UNICEF, Citation1998, Citation2008, Citation2009), and so are consistent with progressive realisation of child rights. Related primary health care measures include health education, community participation in health care decision-making, sanitation and improved water supply; the latter two issues are particularly important now that Zimbabwe faces periodic outbreaks of typhoid and dysentery.

Judged by these criteria, both the MTP and ZimASSET offer a mix of appropriate and inappropriate interventions. The MTP dedicated a separate chapter to ‘Health’, including child health and nutrition. The MTP was right to endorse ‘the Primary Health Care Approach (PHC) … (since) most of the diseases can be prevented or managed at primary health care level’ (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2011:181). However, its argument in favour of PHC was in terms of cost savings rather than impact on maternal or child health (2011:181). The MTP did, however, prioritise the U5MR, the MMR and the major childhood diseases of malaria, tuberculosis and diarrhoea. But it also set a number of unrealistic ‘policy targets', such as ‘100% access and utilisation of comprehensive quality primary health care services and referral facilities by 2015’, reducing the U5MR by almost two-thirds in six years and halting the spread of HIV, things that no country has ever achieved (2011:181–3).

ZimASSET seeks to ‘scale up and strengthen … high impact interventions [such as] … diarrhoea, acute respiratory infections, malaria [and] malnutrition’ (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:67), but gives no details. ZimASSET uses the term ‘primary health care’ only once (2013:66), without defining it. ZimASSET includes a commitment to ‘providing social services encompassing the construction of housing, schools, hospitals and other social amenities, particularly in the new resettlement areas’ (2013:34). Similarly, ZimASSET's results matrices concentrate on the construction and rehabilitation of physical infrastructure and on physical inputs to the health system. In terms of priority services, ZimASSET emphasises ‘basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care’ and a suite of measures related to prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the provision of anti-retroviral therapy to people living with HIV (2013:66), followed by a reduction of diarrhoeal incidence by 50% (from an unspecified baseline), a target of 90% of children fully vaccinated and 90% of mothers delivering their babies in health facilities (2013:67). ‘Medicines and medical supplies (are to be) availed from current 45% to 100%’ (2013:68) and ‘all vacant posts filled’ (2013:71). ‘Reduced stunting’ in children is a desired outcome of ZimASSET's Nutrition Cluster, but the outputs to support that outcome are either of marginal efficacy (‘MCH … nutrition education and counselling’) or are related to micronutrient deficiency, not stunting (2013:58).

In short, ZimASSET's treatment of child health and nutrition lacks any coherence. ZimASSET buries health under Social Services and Poverty Reduction, one of its four clusters, the others being ‘Food Security and Nutrition’, ‘Infrastructure and Utilities’ and ‘Value Addition and Beneficiation’ (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:9–10). Only one of ZimASSET's 10 immediate priority actions (‘quick wins’) under the Social Services and Poverty Reduction Cluster relates to PHC or children; ironically, that ‘quick win’ is the part of PHC that is the hardest and most time consuming to implement, namely ‘access to water and sanitation’ (2013:63).

Neither the MTP nor ZimASSET mentions the high rate of unemployment of recent nursing graduates in Zimbabwe, 2500 in late 2012, and neither document lays out a strategy for improving the quality of care in a system where 69% of the government budget goes to salaries, leaving little fiscal room for supplies, equipment, infrastructure or other quality-enhancing measures (Ministry of Finance, Citation2013).

In education, the focus in Zimbabwe should be on primary education in rural areas. First, the rural areas were those most affected by the crisis (Chimhowu et al., Citation2010). Second, around 70% of Zimbabwean children live in rural areas (ZIMSTAT, Citation2013). Third, this is where the biggest challenges in Zimbabwean education, in terms of both quality and quantity, have always been, and where poverty is greatest (MESC, Citation2000; UNICEF et al., Citation2011; ZIMSTAT, Citation2013). The greatest potential for educational gains thus exists in rural areas, especially the new resettlement areas, where enrolment rates are lowest (ZIMSTAT, Citation2013:34–5).

Judged by these criteria, the MTP was more ambitious than ZimASSET. The MTP included a separate chapter on ‘Education’ and set universal primary education and the restoration of the quality of education as its two first objectives (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2011:188). The MTP also outlined useful measures, such as the abolition of primary school fees and the making of primary education compulsory, which promote universal primary education. But the MTP did not emphasise education in rural areas.

ZimASSET, on the other hand, buries education under the Social Services and Poverty Cluster. None of the ‘quick wins’ in the Social Services and Poverty Cluster of ZimASSET relates to primary or secondary education. ‘E-learning’, leading to ‘computer literate pupils’ (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:90), gets more attention than improving rural primary schools, most of which lack basic supplies such as textbooks, to say nothing of computers.

Both the MTP and ZimASSET fail to address violence in schools. Especially in a society where violence has been so prevalent, public institutions must not add to the problem. Corporal punishment (which may simply re-traumatise children) and sexual abuse in schools (especially of girls by male teachers) deserve serious attention.

Extreme poverty is perhaps the major source of harm to children in the long run. Even in the post-crisis period of 2011/12, 16.2% of Zimbabweans lived in extreme poverty; in rural areas, 30.2% lived in extreme poverty (ZIMSTAT, Citation2013:75). The human rights principles underlying the CRC dictate that priority be given to children living in extreme poverty (UN, Citation1989, Citation2002).

The MTP's title page contained a commitment to ‘sustainable, inclusive growth, human centred development and poverty reduction’. In a separate chapter on ‘Social Protection’, the MTP reviewed the longstanding weaknesses in Zimbabwe's social protection system and set new policy targets and measures. The latter included helping ‘0.4 million chronically poor but non-labour constrained households’ to become more self-sufficient through ‘productive safety nets’ and a commitment to help one million vulnerable children stay in school (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2011:203–6).

ZimASSET, on the other hand, abandons poverty reduction as an overall objective, substituting for it ‘a new trajectory of accelerated economic growth and wealth creation … anchored on indigenisation, empowerment and employment creation’ (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:6). ZimASSET restricts ‘poverty reduction’ to one-half of the Social Services and Poverty Reduction Cluster, and in the results matrices for that cluster ‘poverty reduction’ disappears altogether. ZimASSET sets the modest targets of providing food assistance and medical treatment orders to 100 000 vulnerable (elderly, chronically ill and child-headed) households, and of providing ‘1 000 000 people living in extreme poverty’ with unspecified benefits (2013:74). Even if the full million did receive benefits, however, that would be less than one-half of the 2.1 million people that the government itself estimates live in extreme poverty (calculated from ZIMSTAT, Citation2012, Citation2013).

3.2 Building children's capabilities

The health system, especially PHC, is important in building children's capabilities. Most aspects of the health system's role in building children's capabilities have been addressed in the previous section. Suffice it to say, however, that the contributions of the health sector to building capacities in and by children is simply absent in both the MTP and ZimASSET. While the latter (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:45) denounces the ‘silo mentality’ in the government, there is little evidence in either plan of creative thinking on cross-sectoral collaboration, except in nutrition education for mothers (Citation2013:58). Health and education services, for example, could be designed to support each other through school meals, health education in schools and using schools as platforms for child and adolescent health services.

Education is central to building children's capabilities. Literacy, numeracy and the life skills taught in schools are keys to social and economic success for individuals and for societies (Sen Citation1999; UNICEF Citation1999). The Government of Zimbabwe has repeatedly boasted of its educational achievements in the first decade after Independence (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2000; Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2004; Zimbabwe and United Nations, Citation2010, Citation2012).

Re-building primary education in Zimbabwe's rural areas should be a priority. But secondary and tertiary education also require attention, not least because primary schools need higher level graduates to teach in them. Besides, no country has ever reached sustained economic growth for a generation without at least 20% of the population graduating from secondary school. Building a balanced education system where all children get a good primary education and the most able can progress to good quality secondary and tertiary levels should be the immediate priority.

The MTP proposed a sensible set of priorities, including restoring the quality of education, enhancing the credibility of the local examination management system, retaining and attracting human resources to the sector, reviewing antiquated curricula, provision of adequate teaching and learning materials and the promotion of gender equity at secondary and tertiary levels (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2011:188). The MTP correctly declared that children should not be denied education due to an inability to pay school fees; the MTP also included a commitment to the education of people with disabilities.

However, two education policy objectives in the MTP were problematic. First, by insisting on ‘universal primary education including Early Childhood Development’ (ECD) (Republic of Zimbabwe, Citation2011:188), the MTP tried to build something that the government had never been able to create, maintain or run before, even in earlier times when the government had greater technical and fiscal capacity. While the government promoted ‘early childhood education and care’ (as it was then called) in the 1980s and 1990s, the programme was not successful, and the government admitted as much (MESC, Citation2000). The crisis of the 2000s prevented further progress on ECD programmes – which can bring great benefits, if properly resourced and run (UNICEF, Citation2001). But if it puts an emphasis on ECD, Zimbabwe risks diluting its efforts in the core area of re-establishing quality primary education for all with decent quality secondary and tertiary education for those qualified for it. ZimASSET contains a similar commitment to ‘improve the quality of Early Childhood Development’ (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:39) while making no similar commitment to the quality of primary education.

The second problematic measure in the MTP's education chapter is to ‘promote access to secondary education by every child’. Although no timeframe was specified, universal secondary schooling is unfeasible in the near future. Even universal access to primary school is not yet achieved; the net primary enrolment ratio hovers around 90% (), and in 2009 only 40% of pupils passed the Grade 7 leaving examination (UNICEF-Zimbabwe, Citation2011). Even if all children did meet secondary school entrance standards, there are simply not enough secondary places or secondary teachers.

Figure 8: Net primary school enrolment, Zimbabwe, 1993–2012

Note: Net primary enrolment rates in Zimbabwe tend to be 5 to 10% higher at the beginning of the school year than at the end since some pupils drop out during the school year, which starts in January. Where the survey fieldwork lasted several months, the mid-point was taken. The estimate for October 1999 is probably an underestimate; the government estimated net enrolment of 86.8% (MESC, Citation2000). The figure for 2010/11 is the net attendance rate; attendance is always marginally lower than enrolment.

ZimASSET, on the other hand, has no chapter dedicated to education and no ‘quick wins’ associated with education. ZimASSET conceives of education in terms of ‘human capital development’ (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:65) and as part of ‘indigenisation and empowerment’ (2013:64). It gives priority to ECD (without giving any details) and to higher education, including the construction of three new universities, with hardly a mention of secondary education.

3.3 Dealing with past traumas

Dealing with the psychosocial trauma of children (and adults) is important if individual Zimbabweans are to be able to live not only productive, but happy and healthy lives. Dealing with psychosocial trauma is also important if Zimbabwe is to break the intergenerational cycles of violence, poverty and ill health. The scale of the task is daunting. In 2010/11, 27% of Zimbabwean women aged 15 to 49 said they had experienced physical or sexual violence; only 37% of them sought help (ZIMSTAT & Measure DHS, IFC Macro Citation2012:251). Unfortunately, there are no similar data on children's experience of violence, although qualitative evidence suggests that violence against children is widespread, and takes many forms.

Neither the MTP nor ZimASSET deals with children's psycho-social traumas. The MTP said nothing on the topic. ZimASSET, however, praises the security and defence forces (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:26, 30 and 127) and promises ‘cadetship programmes’ in schools (2013:64).

How a low-income country like Zimbabwe could deal with mass psychosocial trauma is not an easy question. Even if enough trained counsellors were available, Zimbabwe could not afford individual psychosocial counselling for the many traumatised individuals. The few counselling services that exist are mostly in urban areas. Still, there may be ways forward using churches and community groups as healing centres. Groups such as the Africa Community Publishing and Development Trust work on these issues (Bookteam, Citation2011).

At a minimum, the government can commit to delivering all government services in a way that respects the dignity and rights of the client, so as to avoid further harm. The CRC insists on the dignity of the child and the primacy of always acting in the best interests of the child. The CRC also states that children have a right to take part in decisions that affect them, in line with their evolving capacities (UN, Citation1989). ZimASSET takes a step in a positive direction when it establishes an outcome for ‘Client satisfaction’ in the delivery of social services and advocates ‘Service charters’ and client satisfaction surveys (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013:68–9). But such instruments are often ill-adapted to the needs of children, and client satisfaction surveys act only post facto.

Those who have suffered psychosocial trauma, especially children, require special measures. For some forms of trauma, such as sexual assault, it may be possible to set up specialised services at low cost. Other countries have experimented with women's police stations, for example, and with women-and-children-only health clinics. Training and re-training for teachers, health workers and social workers can emphasise the detection, treatment and prevention of gender-based violence, child abuse and other forms of violence. Neither the MTP nor ZimASSET mentions such possibilities.

4. Conclusion

While Zimbabwe has stabilised its economy and re-established a modicum of political and social peace since 2009, most indicators of child welfare do not show improvement. Chronic malnutrition and the MMR have risen to record high levels, while the IMR and U5MR show no sign of declining. In such a situation, investing in the children who are Zimbabwe's future is a policy imperative.

Difficult policy choices must be made. Having dollarised the economy and being cut off from most international capital markets, the Government of Zimbabwe can spend only as much as it can earn. At the same time, faced with strong demands from citizens to ‘do something’, policy-makers have come up with long lists of interventions for immediate implementation. The long lists of interventions proposed in the MTP and ZimASSET lack any sense of priorities. Nor do they provide any sense of cost, feasibility and scheduling requirements (e.g. re-build primary education before expanding secondary or tertiary education). Both the MTP and ZimASSET obfuscate on complicated questions of the public-private mix in service delivery, community participation (including the participation of children), and equity between rural and urban areas, social classes and generations.

In this constrained fiscal environment, the key to a better future for Zimbabwe's children lies in focusing resources on a few high-impact interventions. Breaking the cycle of harm to children, preventing future harms to children and dealing with past traumas will all have to be part of the solution. Just after Independence in 1980, Zimbabwe made a major political commitment to equity and to child welfare. Would that it do so again.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Joan O'Donoghue, Admos Chimhowu, Jeanette Mangengwa, and the DSA editors and reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. The author takes sole responsibility for any remaining errors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

2For World DataBank, see http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx Accessed 5 February 2014. Although methodologically comparable, these are cross-sectional, not panel, surveys.

3Other factors are also playing a role. The World Health Organisation and UNICEF estimate that 29% of the U5MR is neonatal mortality, which is consistent with high levels of maternal malnutrition and poor quality of care in health facilities.

4These categories are not mutually exclusive, but they nonetheless serve a useful heuristic purpose.

References

- Bell, S & Huebler, F, 2011. The quantitative impact of conflict on education, Technical Paper No. 7, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Montreal.

- Bookteam, 2011. Soft strength: Peace-building for development. African Community Publishing and Development Trust, Harare.

- Chagonda, T, 2012. Teachers’ and bank workers’ responses to Zimbabwe's crisis: Uneven effects, different strategies. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 30(1), 83–97. doi: 10.1080/02589001.2012.639656

- Chimhowu, A, Manjengwa, J & Faresu, S (Eds.), 2010. Moving forward in Zimbabwe: Reducing poverty and promoting growth. Brooks World Poverty Institute, Manchester.

- Commission on the Nutrition Challenges of the 21st Century, 2000. Ending malnutrition by 2020: An agenda for change in the millennium: Final report to the ACC/SCN. United Nations, Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub-Committee on Nutrition, New York.

- Comptroller and Auditor General, 1974/75–present. Report of the comptroller and auditor general for the financial year ending 31 June. Government Printer, Harare.

- CSO (Central Statistical Office), 1994. Zimbabwe census 1992: National report. Central Statistical Office, Harare.

- CSO, 1998. Poverty in Zimbabwe. Central Statistical Office, Harare.

- CSO & Institute for Resource Development/Macro Systems, 1989. Zimbabwe demographic and health survey 1988. Central Statistical Office, Harare and Institute for Resource Development/Macro Systems, Calverton.

- CSO & Macro International, 1995. Zimbabwe demographic and health survey 1994. Central Statistical Office, Harare and Macro International, Calverton.

- CSO & Macro International, 2000. Zimbabwe demographic and health survey 1999. Central Statistical Office, Harare and Macro International, Calverton.

- CSO & Macro International, 2007. Zimbabwe demographic and health survey 2005-06. Central Statistical Office, Harare and Macro International, Calverton.

- Government of Zimbabwe, 2004. Zimbabwe millennium development goals: 2004 progress report. Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare, with support from UNDP, Harare.

- Government of Zimbabwe, 2013. Zimbabwe agenda for sustainable socio-economic transformation (ZimASSET). Office of the President and Cabinet, Harare.

- International Crisis Group, 2006. Zimbabwe's continuing self-destruction. Africa Briefing N°38, International Crisis Group, Pretoria and Brussels.

- Inter-Ministerial Committee on SDA Monitoring, 1994. Sentinel surveillance for SDA monitoring: Report of the fourth round. Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare (MPSLSW), Harare.

- Inter-Ministerial Committee on SDA Monitoring, 1995. Sentinel surveillance for SDA monitoring: Report of the fifth round. MPSLSW, Harare.

- Inter-Ministerial Committee on SDA Monitoring, 1996. Sentinel surveillance for SDA monitoring: Report of the sixth round. MPSLSW, Harare.

- Inter-Ministerial Committee on SDA Monitoring, 1997. Sentinel surveillance for SDA monitoring: Report of the seventh round. MPSLSW, Harare.

- Inter-Ministerial Committee on SDA Monitoring, 1999. Sentinel surveillance for SDA monitoring: Eighth round report. MPSLSW, Harare.

- Kuo, C, Operario, D & Cluver, L, 2012. Depression among carers of AIDS-orphaned and other-orphaned children in Umlazi township, South Africa. Global Public Health 7(3), 253–69. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.626436

- MESC (Ministry of Education, Science and Culture), 2000. EFA 2000 assessment: Country report – Zimbabwe. MESC, Harare.

- Ministry of Finance, 2013. The 2013 national budget statement. Ministry of Finance, Harare.

- Mumbengegwi, C, (Ed.), 2002. Macroeconomic and structural adjustment policies in Zimbabwe. Palgrave, London.

- Neugebauer, R, 2005. Accumulating evidence for prenatal nutritional origins of mental disorders. Journal of the American Medical Association 294(5), 621–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.621

- Republic of Zimbabwe, 2000. World summit for children: National end decade report. Government of Zimbabwe, Harare.

- Republic of Zimbabwe, 2011. Zimbabwe medium term plan 2011–15. Ministry of Economic Planning and Investment Promotion, Harare.

- Sadomba, ZW, 2011. War veterans in Zimbabwe's revolution. Weaver Press, Harare.

- Sen, A, 1999. Development as freedom. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- UN (United Nations), 1989. Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations, New York.

- UN, 2002. A world fit for children, A/RES/S-27/2. General Assembly, Twenty-seventh Special Session, United Nations, New York.

- UNICEF, 1994. Children and women in Zimbabwe: A situation analysis update-1994. United Nations Children's Fund, Harare.

- UNICEF, 1996. The state of the world's children 1996. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- UNICEF, 1998. The state of the world's children 1998. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- UNICEF, 1999. The state of the world's children 1999. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- UNICEF, 2001. The state of the world's children 2001. United Nations Children's Fund, New York.

- UNICEF, 2007. The state of the world's children 2007. United Nations Children's Fund, New York.

- UNICEF, 2008. The state of the world's children 2008. United Nations Children's Fund, New York.

- UNICEF, 2009. The state of the world's children 2009. United Nations Children's Fund, New York.

- UNICEF, Centre for Applied Social Sciences & Zimbabwe, 2011. A situational analysis on the status of women's and children's rights in Zimbabwe, 2005–2010: A call for reducing disparities and improving equity. UNICEF, Harare.

- UNICEF-Zimbabwe, 2011. Education in emergencies and post-crisis transition: 2010 report evaluation. United Nations Children's Fund, Harare.

- World Bank, 2014. World dataBank, online at http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx Accessed 5 February 2014.

- Zimbabwe & United Nations, 2010. 2010 millennium development goals: Status report Zimbabwe. Ministry of Labour and Social Services, Harare.

- Zimbabwe & United Nations, 2012. Zimbabwe 2012: Millennium development goals progress report. Ministry of Economic Planning and Investment Promotion, Harare.

- ZIMSTAT (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency), 2012. Census 2012: Preliminary report. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Harare.

- ZIMSTAT, 2013. Poverty income consumption and expenditure survey 2011/12 report. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Harare.

- ZIMSTAT & Measure DHS (Demographic and Health Surveys), IFC Macro, 2012. Zimbabwe demographic and health survey 2010-11. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Harare and Measure DHS, IFC Macro, Calverton.

- ZIMSTAT & UNICEF, 2010. Multiple indicator monitoring survey (MIMS) 2009. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency and United Nations Children's Fund, Harare.