Abstract

This paper examines employment and skills training for community caregivers within the expanded public works programme in South Africa. The paper argues that, as currently conceptualised, the skills and learnership programmes for community caregivers fail to take full advantage of the prevailing labour market realities. Therefore, the paper argues for strategic reconceptualisation of the programme to include learnerships for community caregivers that impart more mid-level to higher-level skills to meet current and future labour market demands particularly in primary health care. This, it is argued, will address the scarcity of skills in the health sector of the economy. Furthermore, the proposed programme will simultaneously have positive impacts on unemployment, the primary health care system and the socio-economic well-being of community caregivers.

1. Introduction

Despite being an upper middle-income country, South Africa has one of the highest poverty and income inequality rates in the world (Leibbrandt et al., Citation2012; Philip, Citation2012) and a high unemployment rate of 25.5%.Footnote2 South Africa's unemployment is chronic and structural in nature and a close association exists between poverty and unemployment (Banarjee et al., Citation2008; Chibba & Luiz, Citation2011). Most of the poor are unemployed low-skilled or unskilled work seekers who lack access to wage income. Moreover, poverty and unemployment have racial and spatial patterns (Leibbrandt et al., Citation2012; Philip, Citation2012; Stats SA, Citation2014). African and coloured populations are disproportionately represented among the poor and unemployed, with unemployment rates of 28.3% and 25.3% respectively, compared with Indians (12.1%) and whites (8.1%)Footnote3 (Stats SA, Citation2014). This is largely attributable to the legacy of previous apartheid government policies of exclusion, discriminatory access to education, deagrarianisation and discouragement of small-holder and peasant farming. These policies contributed to a reduction in employment opportunities in subsistence farming and the loss of sources of income and livelihoods for many Africans, coloured and Indian people (Bhorat & Oosthuizen, Citation2008; Philip, Citation2012).

In the post-apartheid era, the African National Congress government's efforts aimed at redressing the legacy of apartheid have been undermined by major changes in policies and challenges with policy implementation (McGrath & Akoojee, Citation2007; Philip, Citation2012). Nevertheless, some of the government's interventions aimed at reducing unemployment and poverty among disadvantaged groups have had some positive impacts on the livelihoods of poor households. For instance, during 1993–2008, income from social grants increased significantly in real terms and as a share of total household income from 5.4% to 7.9%. There has also been an increase in the mean income of households during this period (Leibbrandt et al., Citation2012). Although there has been a remarkable reduction in unemployment rates over the years from a peak of 31.2% in 2003 to 25.5% in 2014, unemployment remains unacceptably high.

At the same time, South Africa has the largest number of people (5.6 million) living with HIV/AIDS in the world (DoH, Citation2012) and this has exacerbated the problem of poverty especially among AIDS-affected households and communities (Ogunmefun & Schatz, Citation2009; Akintola, Citation2010). AIDS has also impacted the public health system which provides care for a majority of the poor, working-class and unemployed people in the country. As a result of the inability of the health system to cope with the provision of care for the large numbers of HIV-positive people, the government, in 2001, instituted a community/home-based care policy aimed at reducing the burden on the health care system (DoH & DoSD, Citation2001). The policy effectively transfers the responsibility of care to families who are least equipped to provide care (Akintola, Citation2010). Consequently, the responsibility of providing community care has fallen to non-profit organisations who recruit and train volunteer community caregivers to assist families to provide care for the ill (Hayes, Citation2010). However, many of these community caregivers desire to be employed in the health care system (Schneider et al., Citation2008; Akintola, Citation2011).

The South African government has sought to address the problem of unemployment and poverty specifically among the poor through the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) introduced in 2004 (EPWP, Citation2005, Citation2010). The Home and Community Based Care (HCBC) programme is one of the programmes of the EPWP that aims to address the problem of unemployment, especially among unskilled and low-skilled community caregivers working in AIDS care. The programme seeks to provide work and skills training opportunities for unemployed people, resulting in various levels of qualifications to enable them work in various positions in primary and community health care (EPWP, Citation2005).

While there has been some review and evaluation of the EPWP programme (Friedman et al., Citation2007; Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007; EPWP, Citation2010), there is no scholarly work exploring policy options for moving participants in the HCBC programme of the EPWP into more formal sectors of the labour market through higher-level skills training. This paper argues that the HCBC programme presents tremendous opportunities for achieving the EPWP goal of helping unskilled workers bridge into formal employment within the formal health care system. The paper argues that the EPWP could be strategically redesigned to produce intermediate to high-level skilled workers intended to meet the demands of the labour market, and, at the same time, strengthen primary health care (PHC) in South Africa. This paper could inform policy on skills training for job creation and health systems strengthening in South Africa. The paper could also contribute to debates, among academics and policy-makers, about the potential role of public works programmes in poverty reduction and health systems strengthening in the Global South.

2. Community-based care work, unemployment and poverty

2.1 Community-based care and the primary health care system in South Africa

Community caregivers serve as single purpose or multipurpose community health workers providing health care and social services within their local communities. They are predominantly women who are recruited, trained and managed by community-based organisations (CBOs) (Akintola, Citation2008; Schneider et al., Citation2008). Community-based health care services are neither formalised nor integrated within the PHC system since the South African government does not employ caregivers directly but through non-profit organisations (Friedman, Citation2002; Schneider et al., Citation2008; DoH, Citation2009). As a result, many care organisations have challenges accessing financial resources from the government and have to depend on irregular funding from donor agencies or private donors (Akintola, Citation2011; Ogunmefun et al., Citation2012). About 62 455 caregivers were working across the country at the start of the EPWP (EPWP, Citation2004). Although the number of caregivers has increased considerably (EPWP, Citation2010), there are still no current data in the public domain on the number and profile of caregivers in the country and the number receiving remuneration.

Community caregivers provide a range of health and social services to patients, including basic nursing care, health education and assistance with providing and monitoring adherence to tuberculosis drugs. In South Africa, as in other low- and middle-income countries, the need to improve access to antiretroviral (ARV) therapy has led to increasing reliance on community caregivers in the scale up of ARV therapy (Schneider et al., Citation2008; Wouters et al., Citation2012). These ARV therapy programmes have led to positive health outcomes for patients and, in turn, have reduced the need for care of terminally ill patients (Schneider et al., Citation2008; Wouters et al., Citation2012).

Until recently, the majority of community caregivers worked as volunteers and did not receive any stipend (Akintola, Citation2006; Hayes, Citation2010). But there has been an increase in funding from government agencies in recent years (DoH, Citation2009). In 2009, the Department of Health and the Department of Social Development published the community care worker management framework, to manage issues relating to community caregivers who are also referred to as community care workers (DoH, Citation2009). The framework also seeks to standardise practices and remuneration of community caregivers and recommends that community care workers are paid rates that range from R750Footnote4 per month for learners to R2000 per month for supervisors (DoH, Citation2009). However, there are many organisations that are unable to pay their community caregivers any stipend because of a lack of financial resources (Akintola, Citation2011).

Attrition is a major challenge confronting community-based care programmes and could be a consequence of the challenges that caregivers experience while working in these programmes (Akintola, Citation2011; Nkonki et al., Citation2011). Community caregivers confront many challenges, including the physical and psychological burden associated with providing care (Akintola, Citation2006; Akintola et al., Citation2013), lack of recognition by the formal health care system (Schneider et al., Citation2008), poverty among home care patients resulting in lack of money for food and transportation to health facilities, lack of basic protective equipment and materials necessary for infection control, and lack of remuneration or opportunities for employment (Akintola, Citation2006; Akintola & Hangulu, Citation2014).

South Africa's recent policy aimed at ‘re-engineering’ the PHC system proposes a defined role for community health workers within the formal health care system. In this model, community health workers will be employed by the state to work in multidisciplinary teams, led by nurses, to provide outreach services to communities throughout the country (DoH, Citation2010a).

2.2 Community-based care work and poverty

Community caregivers incur opportunity costs when they use their time to provide care. Caregivers could lose valuable time meant to improve community social capital while providing community care. For example, caregivers forego time meant for networking that come from community meetings and social interactions, and opportunities to acquire skills through other capacity development projects (Wiegers et al., Citation2006; Akintola, Citation2008). In addition, some volunteers relinquish opportunities to earn an income from other informal or formal sources when they join community care organisations. Lastly, caregivers could relinquish leisure time and this could have negative impacts on their health and well-being (Wiegers et al., Citation2006; Akintola, Citation2008, Citation2010). A study conducted in six African countries, including South Africa, found that volunteers spent on average 4.6 hours per day providing care (Hayes, Citation2010). A Botswana study found the opportunity cost of providing care by one community caregiver was US$25.23 per month (Ama & Seloilwe, Citation2010). However, these opportunity costs may be invisible to policy-makers and other stakeholders because most community caregivers are unemployed and therefore do not necessarily forego time from productive activities (Akintola, Citation2008).

Community caregivers incur financial costs when they spend their own money to purchase food and medication for their patients. They may also incur financial costs when they pay to transport their patients to clinics/hospitals or buy protective materials such as gloves, masks and aprons (Akintola, Citation2008; Ama & Seloilwe, Citation2010; Akintola & Hangulu, Citation2014). In the Botswana study, Ama & Seloilwe (Citation2010) found that the mean financial cost of home-based care to both family and community caregivers per month was US$65.45 whereas their total mean earning was US$66.00. These costs could increase poverty among caregivers and contribute to household food insecurity (Akintola, Citation2010; Ama & Seloilwe, Citation2010). As discussed in the next section, the HCBC programme of the EPWP seeks to address the problems of unemployment and poverty confronting community caregivers.

3. Public works programmes, job creation and poverty reduction in South Africa

Public works programmes have been used to address HIV and AIDS-related issues in many African countries including Malawi, Botswana, Ethiopia, Kenya, Burundi, Mozambique and South Africa (McCord, Citation2005). In South Africa, the EPWP programme launched in 2004 is one element within a broader government strategy to reduce poverty by increasing employment opportunities. The aim of the first phase of the EPWP was to create one million jobs in the five-year (2004–09) programme life span. It also aimed to empower the unemployed with adequate skills that would increase their capacity to earn an income. Despite the challenges encountered in the implementation of the programme, discussed later, it was declared a success because it achieved its goal of providing employment for a million people a year ahead of schedule (EPWP, Citation2010; Philip, Citation2012).

The first phase of the EPWP had four major sectors: infrastructure; environment and culture; economic; and social. The social sector, which is the focus of this study, focuses on expanding HCBC and Early Childhood Development programmes (EPWP, Citation2005, Citation2010). This sector is implemented through collaboration with the Department of Health and the Department of Social Development (DoH, Citation2009; EPWP, Citation2004, Citation2010).

In the HCBC programme of the social sector, work opportunities comprise: a skills programme that provides on-the-job skills training; and a learnership programme that combines structured learning with work-based skills training (EPWP, Citation2004, Citation2005). Participants who complete these programmes receive a National Qualifications Framework (NQF) qualification in home-based care. The NQF is a series of levels of learning achievements used to grade qualifications in South Africa (SAQA, Citation2012). The EPWP plan indicates that the qualifications obtained in the programme will enable graduates to enter formal employment (EPWP, Citation2004, Citation2005).

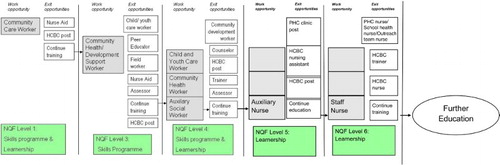

The Health and Welfare Sector Educational Training Authority (HWSETA), a body responsible for organising education and training within the health and welfare sector in South Africa, is responsible for regulating, accrediting and procuring training agencies at the local level for HCBC trainees. As shown in , participants could be accepted to the skills training programme at different NQF levels. Prospective participants with little or no formal education could be enrolled in the skills training programme or learnerships at NQF Level 1. Those with Grade 9 or equivalent qualifications are enrolled at NQF Level 3, while those with Grade 11 or equivalent qualifications are accepted at NQF Level 4 of the skills training or learnership programmes.

Figure 1: Overview of the current HCBC skills training and learnership programme

Prospective participants could be accepted into the NQF Level 1 of the skills training programme to work as community care workers or to the NQF Level 3 of the programme to work as community health/development support workers. They could also be accepted to the NQF Level 4 to work as, for example, community and youth care workers. With regards to the learnership programme, participants could be accepted for training to qualify at NQF Level 1 as nurse aids or to function in HCBC posts and could thereafter apply to continue training at the next higher level (NQF Level 3). Participants could also be accepted for training to qualify at different NQF Level 3 cadres such as child/youth care workers. They could thereafter apply for training at NQF Level 4. Lastly, participants could enrol to receive training to qualify for different NQF Level 4 cadres such as community development workers. Participants spend 12 to 24 months in the skills training and learnerships before exiting the programme (see EPWP, Citation2004).

The current model helps provide needed skills for previously unskilled caregivers. Participants also receive income that helps address the issue of poverty among community caregivers. However, one of the major shortcomings of the model is that it does not allow for the development of medium to higher-level skills because those who graduate with NQF Level 4 are not able to apply for continuing training within the programme. This and other shortcomings of the current programme are discussed in detail later.

In the first five years (2004–09), the EPWP provided 113 172 short-term (12 to 24 months) job and training opportunities for community caregivers who were previously unemployed (EPWP, Citation2005, Citation2010). By the 2006/07 financial year 31 158 caregivers were receiving stipends, while 42 473 work opportunities were created for caregivers in 2008/09 (EPWP, Citation2010). Those at NQF Levels 1 and 2 received R500 while those at NQF Levels 3 and 4 received R1000. These rates reflect the disparities in remuneration arising from the different rates paid by the different government departments prior to the start of the EPWP. In addition, the EPWP stipulated payment of different rates for those at different NQF levels. However, there are efforts to standardise remuneration at R1500 (EPWP, Citation2011a).

In Phase II of the programme, a number of changes were introduced including a relaxation in the requirement to exit the programme after a 24-month period. Furthermore, the primary programme output was changed from the number of temporary work opportunities to the number of full-time equivalents created. Full-time equivalent refers to one person-year of employment, which is equivalent to 230 person-days of work (EPWP, Citation2011a). In addition, the non-state sector was established to mobilise capacity outside the state, including the not-for-profit organisations, to create work opportunities for the EPWP target group. Also in Phase II of the programme, the obligation for training has been weakened. Training is now provided only in programmes or projects where training is deemed to be essential for the participants to do the work they have been assigned in the EPWP (EPWP, Citation2011a).

Although some volunteers benefit from the EPWP as currently practiced, there are a number of challenges with the programme. The focus of this paper is on the challenges which relate specifically to the HCBC programme within the social sector. First, despite considerable expansion in the scale of the programme over the past six years, a substantial proportion of care organisations still do not receive any funding from the EPWP. Data on the proportion of organisations receiving funding are also not available (see also Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007).

Second, only a certain number of caregivers, usually 10 people, are funded in one care organisation. The remaining caregivers within the same organisation have to wait their turn (EPWP, Citation2004; Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007; Akintola, Citation2011). Third, in Phase I of the programme, allowance was made for only a fraction (14.2%) of the participants in the HCBC programme to benefit from the learnerships which are designed to equip them with skills that will serve as a bridge into formal employment (McCord, Citation2008). In addition, there are challenges with providing training for those who qualify. In some provinces, there has been a delay in the certification of qualifications and this has affected participants’ employment prospects (Phillips et al., Citation2009). The EPWP has also experienced a shortage of trainers which has undermined the training of participants and their progression to higher levels. In addition, exit strategies have been few; that is, most of those who complete training did not find employment (Phillips et al., Citation2009; EPWP, Citation2011b).

In Phase II of the programme, a smaller proportion of participants will benefit from training because of the weakening of the obligation for training of EPWP participants (see EPWP, Citation2011a). The majority of participants in the programme therefore remain in low-skilled work and have little prospect of moving into medium to high-skilled formal employment once they exit the programme. Fourth, as stated earlier, there are no learnership programmes above NQF Level 4 to accommodate those who have received training at lower levels and want to apply to study at higher levels or those with a matriculation qualification (obtained after completing the highest grade of high school education).

The challenge confronting the social sector of the EPWP therefore is how to create learnerships that provide training on skills which are urgently needed in the South African labour market. The next section provides a discussion of a proposal to address some of the challenges identified in the current EPWP, and the potential challenges that need to be overcome to make the proposal work.

4. Can public works create formal employment for community caregivers?

4.1 Securing livelihoods and strengthening the primary health care system

This paper argues that the EPWP provides a unique opportunity to not only use economic policy to create short-term employment among poor caregivers but to also develop human capital that is necessary for strengthening the health system in South Africa. McCord (Citation2008) argues that, of the four sectors under the EPWP, the social sector has the greatest potential for providing intermediate to high-level skills for participants that will enable them to enter employment because of the availability of demand for such skills.

Despite some notable progress that the EPWP has made in creating jobs and reducing poverty (McCord, Citation2008), this paper argues that the HCBC sub-sector has failed to take full advantage of the South African labour market dynamics and realities. Given the limitations confronting the sub-sector discussed earlier, this paper argues that the HCBC sub-sector, as currently conceptualised and implemented, does not provide sufficient skills that will make caregivers employable in jobs that will pull them out of poverty.

If the HCBC programme is to contribute to the achievement of the EPWP's broad goal of pulling people out of poverty, there is a need for the programme to address the following. (a) Expand the current skills programme significantly by increasing the proportion of caregivers in the skills programme in order to open up opportunities for skills training for many more caregivers. (b) Increase the number of learnerships available at intermediate levels such as NQF Levels 3 and 4 so that many more participants can exit the programme with intermediate-level skills. (c) Create employment for graduates of the current programme in permanent positions within the health, welfare and development sectors. This will require both a planned and deliberate employment of programme graduates in vacancies within government health and social/development focused institutions/agencies. A systematic increase in departmental budgets to create vacancies where the need exists for such skills but where vacancies do not currently exist is also warranted. (d) Rethink the career trajectory of community caregivers within the EPWP. In this regard, there is a need to move beyond the provision of temporary employment to creating clearer career paths for community caregivers. Caregivers should be trained to acquire higher-level skills beyond the current highest possible (NQF Level 4) qualifications to enable some of the learners to exit with NQF Level 5 and 6 qualifications. This will require a considerable expansion of the current learnerships to equip learners with intermediate to high-level skills that will enable them to enter the labour force in the formal economy and fill spaces where there are significant skills deficits. This should provide job opportunities for some of the caregivers and ultimately lead to more secure employment in the public health system.

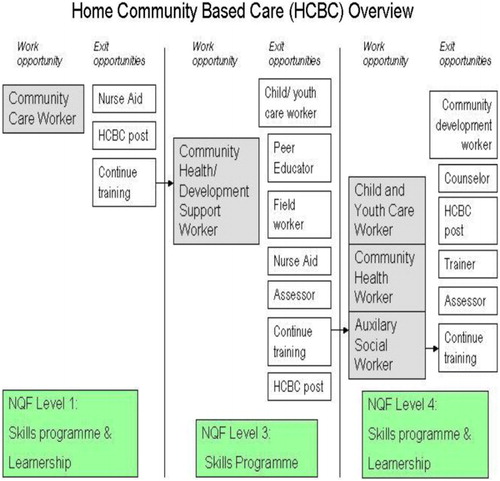

In the proposed programme, participants will be funded to undergo training as is the case with the current programme. However, those who excel and have a strong motivation to further their studies will move beyond training merely as community health workers, as is the case currently, into intermediate to higher-level skilled work (see ).

Currently, there are skills shortages in the health, social welfare and education sectors and the government has declared certain professions, such as nursing and social work, as scarce skills (DoE, Citation2006; Day & Gray, Citation2008; Earle, Citation2008; Wildschut & Mqolozana, Citation2008). A recent study reveals that 40.3% of professional nursing posts are vacant (Day & Gray, Citation2008). Furthermore, only 8% of the pharmacy assistants needed are currently employed in the public health sector (DoH, Citation2010a). These capacity problems are more severe in public health facilities located in semi-rural and rural areas (Earle, Citation2008; Wildschut & Mqolozana, Citation2008). For example, only 19% of nurses in the public health sector serve the 43.6% of South Africans living in the rural areas (DoH, Citation2011a).

The proposed programme could proceed in phases, starting with a pilot phase that trains community caregivers in one field/career area where there is significant demand for skills such as nursing. It could then be scaled up gradually into other career fields in health and social services. The EPWP programme will need to expand the current learnerships (where the highest exit level is NQF Level 4) to allow outstanding graduates of the current learnerships to continue training in accredited nursing schools, and exit the programme with certificates in nursing at NQF Level 5, while those who show exceptional promise could be enrolled in a nursing diploma training to exit at NQF Level 6. An exhaustive list of criteria for inclusion of participants in the new programme is beyond the scope of this paper, but should at a minimum include those who excel in their work as community caregivers, have relevant qualification for further studies and excel in their current learnership programme. Additional criteria could be drawn up at the community level through community participation to suit the specific needs of the communities.

4.2 Prospects and challenges

The proposed programme could have multiple benefits and multiplier effects. The programme could benefit individuals, households, communities, the health care system and, ultimately, the country's economy because of its potential impact on the pool of unskilled/low-skilled unemployed workers. The focus of the programme on community caregivers who are currently working in CBOs will make it easier to target unemployed people in poor communities experiencing the deleterious impacts of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Many of the graduates could be employed within and around their own communities since the poor and rural communities impacted by AIDS are also the same areas where there are critical skills shortages (Earle, Citation2008; Wildschut & Mqolozana, Citation2008; DOH, Citation2011a). This could help strengthen social and psychological capital among caregivers who may be inspired to acquire higher-level skills. The provision of employment opportunities for poor people should help reduce poverty and improve household food security. This could also have multiplier effects on the local economy (Friedman et al., Citation2007). The proposed programme should help strengthen the health systems by developing human capacity and improving PHC delivery. Additionally, the programme should help free up time (see Akintola, Citation2008) for community caregivers since community caregivers will work as paid employees providing support to AIDS-affected families. It could also free up time for family caregivers to work in the informal or formal economy (Wiegers et al., Citation2006; Akintola, Citation2008, Citation2010).

Despite the potential benefits of this proposed programme, a range of challenges must be anticipated. These challenges relate to a mix of governance, financial and delivery issues in the current and proposed programmes. Firstly, government does not have comprehensive and accurate information regarding the number and profile of all home-based care organisations, their volunteer workers and the needs of the communities that they serve (Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007; EPWP, Citation2010). A mapping of all home-based care programmes in the country is warranted in order to establish a reliable and up-to-date database. Closely related to this are the challenges associated with implementing the current programme both at the national and provincial levels, discussed extensively by Friedman et al. (Citation2007) and Parenzee & Budlender (Citation2007) and acknowledged in the reports of the EPWP (EPWP, Citation2004, Citation2005, Citation2010, Citation2011a). These challenges exist within and across the government departments tasked with implementing the programme and include, among others, the differing understanding and interpretation of the EPWP policy and the implementation and reporting of the programme across departments and provinces (Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007; Phillips et al., Citation2009).

Additionally, human capacity challenges and problems with relationships and role clarification within and between government departments at the national and provincial levels need to be addressed. At the provincial level which is responsible for service delivery, the performance of the implementing partners has been fraught with challenges making it impossible for EPWP delivery targets to be achieved (Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007; Phillips et al., Citation2009). It has also led to inconsistency and non-uniformity in performance across provinces. Another complicating factor is that the various provinces have different levels of human resources, infrastructural capacity and service delivery records, which have impacted on their ability to deliver on EPWP goals (Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007). These challenges are also reflected in the dearth of accurate and consistent data on various aspects of the programme, as acknowledged in the EPWP five-year report (see also Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007; EPWP, Citation2010).

There is a concern that the widespread introduction of ARV therapy could lead to a reduction in the need for caregivers. However, community caregivers will still be needed to provide care and support for the 29% of people living with HIV and AIDS in South Africa who do not have access to ARV therapy (WHO, Citation2013). In order for community caregivers to contribute to PHC strengthening, there is a need for an expansion in the scope of the learnerships to enable the production of more generalist multi-skilled and multi-purpose community health workers. These caregivers should be trained to, among other practices, assist with ARV and tuberculosis treatment and adherence, provide care for people with a wide range of infectious or chronic diseases, and provide care for family caregivers, some of whom are older caregivers who may be frail and in dire need of care and support (Akintola, Citation2006; Ogunmefun & Schatz, Citation2009; Akintola & Hangulu, Citation2014).

One major challenge is that of funding. To begin with, there is a need to estimate the cost of executing this proposal. Further, the EPWP and different community-based initiatives currently have partnerships with international development partners in the country (Friedman et al., Citation2007; Phillips et al., Citation2009). These partnerships need to be expanded and nurtured in order to build a more comprehensive funding architecture.

In order to access more sustainable financial and technical resources, the EPWP should be aligned with the National Health Insurance policy as well as other existing government policy frameworks such as the policy on the development of human resources for health as outlined in the human resources strategy for the health sector, the policy on PHC re-engineering, and the community care worker management policy framework. These policy initiatives are reflected in the National Department of Health Strategic plan for 2010/11–2012/13 and aim to improve human resources planning, development and management. The PHC re-engineering policy initiative, which aims to deliver quality, effective and efficient PHC services to the poor and underprivileged, also contains an explication of some of the key activities for achieving the goal of human resource development at the primary care level. Among these are the training of PHC personnel and mid-level health workers as well as the refurbishment and re-opening of nursing schools and colleges in order to increase the production of nurses (DoH, Citation2009, Citation2010b, Citation2011a, Citation2011b).

However, aligning the training, for example, of nurses with existing accredited schools could pose a challenge. This will require that this proposal is aligned with the Strategic Plan for Nursing Education, Training and Practice 2012/13–2016/17 (DoH, Citation2013). Further, there is a need for the Department of Health to provide financial and technical support for the alignment of the proposed EPWP learnerships with existing nursing training facilities and those that will be built as part of the National Health Insurance. A related challenge is that of ensuring that the training programme does not undermine health services delivery. The EPWP should work with nursing colleges to develop a system of training that will allow trainees to work in home-based care and other community health initiatives as part of their practical training and internship. This will enable them to provide home care services within the proposed PHC initiative while still in training, thereby ensuring continuity in health service delivery. It will also help bring in more caregivers to the pool of those receiving skills training and income (EPWP, Citation2004) and could help address the shortage of nurses in PHC (Akintola, Citation2011; DoH, Citation2011a).

Essentially, the proposed programme should be conceptualised as a model of community-based care that creates low-level skilled jobs on the one hand and career paths into mid to higher-level skilled jobs as well as health systems strengthening on the other (Friedman et al., Citation2007; DoH, Citation2010b, Citation2011a; Akintola, Citation2011). The model must therefore allow caregivers time off work in order to receive training, for example, in nursing schools closest to their communities. The challenge for the EPWP will be to work out a system of relief and succession that ensures new recruits from the pool of caregivers waiting their turn to be absorbed into the EPWP are enrolled in the programme to replace caregivers who have been selected for further training. In order for the proposed programme to be successful in strengthening the health systems for effective delivery of health services, there is the need to address issues related to logistics and the availability of material resources. In aligning the proposed programme with the National Health Insurance and PHC re-engineering initiatives, policy-makers should address issues relating to transportation of patients to clinics and hospitals. A mechanism should also be put in place to ensure the availability of medication and food for patients as well as the regular supply of good quality material resources necessary for the provision of home care such as gloves and other protective equipment (Akintola, Citation2008; Akintola & Hangulu, Citation2014). This should help reduce the burden on caregivers who use their resources to help needy patients.

An existing problem with the current EPWP which could undermine the proposed programme is the shortage of trainers for the skills training and learnership programmes and the alignment of the qualifications to NQF standards by the HWSETAs (Parenzee & Budlender, Citation2007; EPWP, Citation2011b). There is a need for the HWSETA to work more closely with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and CBOs if they are to assist in the training of learners on the EPWP. Given that NGOs and CBOs play a critical role in home-based care specifically, and in PHC more broadly, there is an urgent need for the EPWP to form partnerships with a wide array of international development agencies, international NGOs, faith-based organisations and CBOs for the following reasons: NGOs and CBOs could use their in-house trainers to provide training for EPWP beneficiaries in the low-skills categories using the EPWP curriculum approved and accredited by HWSETA; and NGOs and CBOs providing community-based care could also host trainees of the proposed programme, thereby providing an opportunity for them to acquire practical skills and experience.

The challenge of creating jobs for graduates of the learnerships at various levels should be addressed with the alignment of the proposed programme with the various policy frameworks discussed earlier. Graduates could be employed in positions for nurses and Community Health Workers that will be created at the primary care level (through the extension of the comprehensive package of services offered at the primary care level), in community outreach teams, community health facilities and clinics and school health programmes (DoH, Citation2011a, Citation2011b). The EPWP needs to partner with other funding agencies to commit funds for creating posts within NGOs and CBOs in order to accommodate some of the graduates of the proposed programme at the different skill levels. There is also a need for government to provide adequate funding and other forms of support to CBOs so that they are in a position to employ graduates of the current skills training and learnership programmes.

5. Conclusions

The EPWP, which was designed to reduce unemployment among low-skilled South Africans, has had some measure of success in providing employment for the poor. While the social sector has the potential for having the greatest impact on poverty (McCord, Citation2008), the HCBC programme has led to only minimal reductions in poverty levels in participants’ households. This is because the nature of the skills training provided does not match current demands in the South African labour market. Although there is huge demand for skills in certain sectors of the economy in South Africa, the EPWP has yet to take advantage by supplying workers with skills to work in these sectors.

This paper has discussed a demand-led proposal to improve employment prospects and secure livelihoods for HCBC participants in the social sector of the EPWP. The proposal aims to draw more people into the skills training programme and improve the level of skills offered in order to take advantage of demand trends in the South African health sector. The paper has argued that this proposed programme will empower participants with higher-level skills that will enable them to enter the labour force in more secure positions in sectors where there are significant demands and good prospects for long-term employment. It seeks a win–win situation for an economy that has severe skill shortages in the health sector on the one hand and a large number of unemployed people who could be trained to fill critical vacancies on the other.

This proposal requires strategic re-conceptualisation of the HCBC programme within the social sector of EPWP, from one that creates short-term employment to one that creates career paths which can help beneficiaries to bridge into the formal health care system in South Africa.

Acknowledgements

Some of the ideas discussed in this paper were presented at the International Conference on Employment Guarantee Policies: Theory and Practice at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, USA, 12–14 October 2006. The author is grateful to participants at the conference for their feedback. The author would also like to thank Michael Eley for providing technical assistance. The author is very grateful to the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo, Norway and the Program in Policy Decision-making, Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada for hosting him while preparing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2These figures refer to the narrow definition of unemployment, which includes only current job seekers and excludes discouraged job seekers. The rate of unemployment using the expanded definition is 35.6% (Stats SA, Citation2014).

3The use of this race classification is not intended to legitimise these racist terminologies but it is used to differentiate the unemployment and poverty rates among different groups in order to inform policy.

4One US Dollar is equivalent to approximately 12 South African Rand.

References

- Akintola, O, 2006. Gendered home-based care in South Africa: More trouble for the troubled. African Journal of AIDS Research 5(3), 237–47. doi: 10.2989/16085900609490385

- Akintola, O, 2008. Unpaid HIV/AIDS care in Southern Africa: Forms, context, and implications. Feminist Economics 14(4), 117–47. doi: 10.1080/13545700802263004

- Akintola, O, 2010. Unpaid HIV/AIDS care, gender and poverty: Exploring the links. In Antonopoulos, R & Hirway I (Eds.), Unpaid work and the economy: Gender, time use and poverty. Palgrave-Macmillan, London. pp. 112–39.

- Akintola, O, 2011. What motivates people to volunteer? The case of volunteer AIDS caregivers in faith-based organisations in KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa. Health Policy and Planning 26(1), 53–62. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq019

- Akintola, O & Hangulu, L, 2014. Infection control for home-based care for people living with HIV/AIDS/TB in South Africa. An exploratory study. Global Public Health. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.895405. Accessed 8 April 2014.

- Akintola, O, Hlengwa, WM & Dageid, W, 2013. Perceived stress and burnout among volunteer caregivers working in AIDS care in South Africa. Journal of Advanced Nursing 69(12), 2738–49. doi: 10.1111/jan.12166

- Ama, NO & Seloilwe, ES, 2010. Estimating the cost of care giving on caregivers for people living with HIV and AIDS in Botswana. A cross-sectional study. Journal of the International AIDS Society 13(14), 1–8.

- Banarjee, A, Galian, S, Levissohn, J, McLaren, Z & Woolard, I, 2008. Why has unemployment risen in the New South Africa?. Economics of Transition 16(4), 715–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0351.2008.00340.x

- Bhorat, H & Oosthuizen, M. 2008. Employment shifts and the ‘Jobless growth’ debate. In Kraak, A & Press, K (Eds.), Human resources development review: Education, employment and skills in South Africa. HSRC (Human Sciences Research Council) Press, Cape Town. pp. 50–68.

- Chibba, M & Luiz, JM, 2011. Poverty, inequality and unemployment in South Africa: Context, issues and the way forward. A Journal of Applied Economics and Policy 30(3), 307–15.

- Day, C & Gray, A, 2008. Health and related indicators. In Barron, P & Roma-Reardon, J (Eds.), South African health review 2008. Health Systems Trust, Durban. pp. 239–96.

- DoE (Department of Education), 2006. The national policy framework for teacher education and development in South Africa: More teachers: Better teachers. Department of Education, Pretoria.

- DoH (Department of Health), 2009. Community care worker policy management framework (distribution copy). Department of Health, Pretoria.

- DoH (Department of Health), 2010a. Re-engineering primary health care in South Africa. National Department of Health Discussion Paper. Department of Health, Pretoria.

- DoH (Department of Health), 2010b. National department of health strategic plan 2010/11–2012/13. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- DoH (Department of Health), 2011a. National health insurance in South Africa: Policy paper. Government Notice 657 of 12th August 2011, Gazette Number 34523. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- DoH (Department of Health), 2011b. Human resources for health South Africa: HRH strategy for the health sector in South Africa 2012/13–2016/17. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- DoH (Department of Health), 2012. The 2011 national antenatal sentinel hiv and syphilis prevalence survey in South Africa. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- DoH (Department of Health), 2013. Strategic plan for nursing education, training and practice 2012/13–2016/17. Department of Health, Pretoria.

- DoH & DoSD (Department of Health & Department of Social Development), 2001. Integrated home/community based care model options. Department of Health, Pretoria.

- Earle, N, 2008. Social Workers. In Kraak, A & Press, K (Eds.), Human resources development review: Education, employment and skills in South Africa. HSRC (Human Sciences Research Council) Press, Cape Town. pp. 432–50.

- EPWP (Expanded Public Works Programme), 2004. Social sector plan 2004/5–2008/9, Version 5, 24 February. Department of Public Works, Pretoria.

- EPWP (Expanded Public Works Programme), 2005. Introduction to the expanded public works programme. http://www.epwp.gov.za Accessed 22 October 2010.

- EPWP (Expanded Public Works Programme), 2010. Expanded public works programme five year report: 2004/5–2008/9 – Reaching the one million target. www.epwp.gov.za/downloads/EPWP_Five_Year_Report.pdf Accessed 10 July 2011.

- EPWP (Expanded Public Works Programme), 2011a. Environment and culture sector epwp phase ii logframe: 2010–2014. www.epwp.gov.za/documents/Sector%20Documents/Environment%20and%20Culture/Logframe_for_the_EC_Sector_FINAL(2010-2014).pdf Accessed 5 August 2011.

- EPWP (Expanded Public Works Programme), 2011b. Training guidelines for the social sector. http://www.epwp.gov.za/documents/Sector%20Documents/Social/Training_Guidelines_for_the_Social_Sector.pdf Accessed 2 October 2013.

- Friedman, I, 2002. Community based health workers. In Ijumba, P, Ntuli, A & Barron, P (Eds.), South African health review. Health Systems Trust, Durban. pp. 161–80.

- Friedman, I, Bhengu, L, Mothibe, N, Reynolds, N & Mafuleka, A, 2007. Executive summary: Scaling up the EPWP social cluster. Unpublished paper for the DBSA Development fund and the EPWP social cluster, November. Health Systems Trust, Durban.

- Hayes, S, 2010. Valuing and compensating caregivers for their contributions to community health and development in the context of HIV/AIDS: An agenda for action. The Huairou Commission, New York.

- Leibbrandt, MA, Finn, A & Woolard, I, 2012. Describing and decomposing post-apartheid income inequality in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 29(1), 19–34. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2012.645639

- McCord, A, 2005. Public works in the context of HIV/AIDS: Innovations in public works for reaching the most vulnerable children and households in east and Southern Africa. Unpublished report of the South African Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU), Public Workers Research Project, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- McCord, A, 2008. Training within the South African national public works programme. In Kraak, A & Press, K (Eds.), Human resources development review: Education, employment and skills in South Africa. HSRC (Human Sciences Research Council) Press, Cape Town. pp. 555–75.

- McGrath, S & Akoojee, S, 2007. Education and skills for development in South Africa: Reflections on the accelerated and shared growth initiative for South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development 27(4), 421–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.07.009

- Nkonki, L, Cliff, J, Sanders, D, 2011. Lay worker attrition: Important but often ignored. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 89(12), 919–23. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.087825

- Ogunmefun, C & Schatz, E, 2009. Caregivers’ sacrifices: The opportunity cost of adult morbidity and mortality for female pensioners in rural South Africa. Development Southern Africa 26(1), 95–109. doi: 10.1080/03768350802640123

- Ogunmefun, C, Friedman, I, Mothibe, N & Mbatha, T, 2012. A national audit of home and community-based care (HCBC) organisations in South Africa. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 7(4), 328–37. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2012.673754

- Parenzee, P & Budlender, D, 2007. South Africa's expanded public works programme: Exploratory research of the social sector. Unpublished paper, ON PAR and Community Agency for Social Enquiry, Cape Town.

- Philip, K, 2012. The rationale for an employment guarantee in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 29(1), 177–90. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2012.645650

- Phillips, S, Harrison, K, Mondlane, M, Van Steendene, G & Altman, M, 2009. Evaluation of the expanded public works programme (EPWP) in the North West. Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria.

- SAQA (South African Qualifications Authority, 2012. Glossary of terms: South African qualifications framework. www.statssa.gov.za/publications/publicationschedule.asp Accessed 20 June 2012.

- Schneider, H, Hlophe, H & Van Rensburg, D, 2008. Community health workers and the response to HIV/AIDS in South Africa: Tensions and prospects. Health Policy and Planning 23(3), 179–87. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn006

- Stats SA (Statistics South Africa), 2014. Quarterly labour force survey: Quarter 2 2014. Statistical release P0211. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria. www.statssa.gov/Publications/P0211/P02113rdQuarter2013.pdf Accessed 24 August 2014.

- Wiegers, E, Curry, J, Garbero, A & Hourihan, J, 2006. Patterns of vulnerability to AIDS impacts in Zambian households. Development and Change 37(5), 1073–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2006.00513.x

- Wildschut, A & Mqolozana, T, 2008. Shortage of nurses in South Africa: Relative or absolute? Report prepared for the HRSC Department of Labour, Pretoria.

- WHO (World Health Organization), 2013. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: Results, Impact and Opportunities. WHO Report. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Wouters, E, Van Damme, W, Van Rensburg, D, Masquillier, C & Meulmans, H, 2012. Impact of community-based support services on antiretroviral treatment programme delivery and outcomes in resources-limited countries: a synthetic review. BMC Health Services Research 12, 194. http://www.biomedcentral.com/147-6963/12/194 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-194