ABSTRACT

Conventional mass tourism shortcomings have facilitated the origin of alternative forms of tourism such as community-based tourism (CBT). Lately, another form of tourism known as ‘Albergo Diffuso’ (AD) has also been mentioned as a possible strategy to revive depressed specific local contexts, such as townships, villages and small towns. This article’s aim is twofold: first to contextualise the concept of AD in the South African milieu and secondly to investigate the possible relationship and role that CBT and AD could have. In this context, specific characteristics and similarities between CBT and AD are explored. The article’s main contribution concerns the exploration of the AD concept as an alternative form of tourism related to local community development. This is the first time that this concept has been presented in a South African context.

1. Introduction

Tourism statistics demonstrate the pronounced relevance of tourism worldwide, since it is now readily recognised as one of the leading sectors globally, with the 2030 international tourism figures forecast to reach the considerable amount of 1.8 billion tourists (UNWTO, Citation2014:2). Importantly, during the last decades tourism has reached more destinations and territories; thus, ‘destinations worldwide have opened up to, and invested in tourism, turning tourism into a key driver of socio-economic progress through export revenues, the creation of jobs and enterprises, and infrastructure development’ (UNWTO, Citation2014:2). While traditionally strong destinations will continue to grow their tourism sector, new emerging destinations ‘are expected to increase at twice the rate of those in advanced economies’ (UNWTO, Citation2014:2). Beside its economic value and role in poverty alleviation, Yang & Hung (Citation2014:883) also specifically mention that: ‘Different from other economic activities that developed areas in competitiveness, several less developed regions also share advantageous positions in the tourism arena as worldwide popular destinations.’

The positive picture painted is not without gaps and problems, however. Thus, conventional mass tourism has been criticised, and alternative forms of tourism development aimed at being ‘supposedly able to deliver better outcomes in development (specifically in the context of developing countries with disadvantaged communities)’ have been proposed; since the 1980s ‘alternative concepts of tourism have gained attention … ’ (Giampiccoli & Saayman, Citation2014:1667). At the same time, and importantly, studies (Gartner & Cukier, Citation2012; Saayman et al., Citation2012) have also revealed that doubt has risen about the supposedly positive relationship between tourism growth and poverty alleviation. The negative impacts and unwelcome side-effects that tourism can bring about if not properly managed ‘have led to the growing concern for the conservation and preservation of natural resources, human well-being and the long-term economic viability of communities’ and pointed to the need for decision-makers to search ‘for alternative tourism planning, management and development options’ (Choi & Sirakaya, Citation2006:1274). Attempts have been made to offset and reduce the aforementioned matters together with the problem of dependency, by adopting alternative tourism development forms such as community-based tourism (CBT) (Dolezal, Citation2011:130).

Keeping this context in mind as an introductory background, this article investigates a possible relationship between CBT and ‘Albergo Diffuso’ (AD) as an alternative attempt to revive townships, villages and small towns in South Africa. The concepts of AD are explored and possible AD development models are also indicated. In a similar but briefer approach, relevant matters related to CBT are mentioned. At the same time, the concepts and matters related to AD and CBT are interlinked and the article presents possible relationships between the two concepts. Based on this, the aim of the article is twofold: first to introduce the concept of AD in the South African milieu and secondly to identify the possible relationship and role that CBT and AD could have.

AD is an Italian concept where ‘Albergo’ means Hotel and ‘Diffuso’ implies ‘extended’, ‘dispersed’, ‘scattered’, ‘spread’, ‘diffused’ and ‘widespread’ (Tagliabue et al., Citation2012:1061; Monge et al., Citation2015:69; Bulgarelli, Citationn.d.:2). Therefore AD means a ‘spread’ or ‘scattered’ hotel in a specific location (e.g. a village or small town), spread through various buildings. To avoid confusion and for simplicity, this article uses the acronym ‘AD’. This option is proposed as relevant because it could contribute to reviving /rejuvenating depressed local contexts, since AD is based on influencing and benefiting the community at large rather than just the single owner of a specific hotel (see for example Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:7). Widespread benefits at community level are also characteristics of CBT since its 1970s origin linked it to alternative development approaches (see Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:3).

Since its origin, CBT has promoted debates: in 2006 it was already being stated that ‘there has been a proliferation of research and literature around the concept of “Community Based Tourism”’ (Beeton, Citation2006:50). For example, many studies ‘debated on whether or not community-based tourism does indeed empower locals’ (Sin & Minca, Citation2014:98). Therefore, while matters related to CBT are not excluded from this article, the major focus is on the concept of AD. This is also because while CBT studies in the South African context have been present since at least the last 1990s (see for example Naguran, Citation1999; Ndlovu & Rogerson, Citation2004; Boonzaaier & Philip, Citation2007; Malatji & Mtapuri, Citation2012; Giampiccoli et al., Citation2014), no study or other document seems to have been published on AD in relation to the South African context.

2. Literature review

Before one examines CBT and AD, it is necessary to keep in mind that one important reason behind their development and possible success has been the change related to tourist behaviours, requirements and experience needs. This has been evidenced in relation to both CBT and AD. Although different levels of ‘luxury’ and facilities may be present, the underpinning reasons for visitors to go to or use CBT and AD seem very similar. Thus, within the context of new postmodern tourists (Quattrociocchi & Montella, Citation2013:115, translated from Italian; on similar matters see also Vallone & Veglio, Citation2013:696; Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:3) both AD and CBT visitors search for authentic experiences and immersion into the local context (see for example Dolezal, Citation2011:129; Fiorello & Bo, Citation2012:762 for CBT; and Liçaj, Citation2014:85; Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:3 for AD). Consideration of these background issues pertaining to tourists’ behaviours is important, in order to better understand the possible value to tourist markets of AD and CBT.

The tourism industry is struggling to succeed in its developmental aims. To this extent, the tourism sector has been ‘criticised for its high leakage, low payment and low participation of locals’ (Yang & Hung, Citation2014:883) while at the same time, and possibly as a consequence, the tourism sector is always changing. It produces new forms of tourism, one of which has been CBT (Mearns & Lukhele, Citation2015:2). CBT emerges as one of the possible alternative tourism approaches to mass tourism and is often seen as a new panacea in ‘bottom-up’ tourism development (Sin & Minca, Citation2014:98). However, CBT is not a panacea and while it has potential, attention needs to be given to its implementation to be sure that CBT can achieve positive results (Suansri, Citation2003:7; Ellis & Sheridan, Citation2014:1). As a result: ‘Several studies have raised the idea that wide-scale community participation in community-based organisations has a significant role in poverty alleviation’ (Yang & Hung, Citation2014:884). Despite the various definitions attributed to CBT, it is proposed here that CBT is a type of tourism that ‘is managed and owned by the community, for the community … ’ (George et al., Citation2007:1; see also Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:3). There is no impediment to CBT development in various settings. Such development has taken place in both developed and developing environs (see for example various case studies in Asker et al., Citation2010) and can take place in both rural (as it often does) and more urban contexts (Rogerson, Citation2004:25). CBT has been associated with a number of other characteristics such as a need to distribute benefits to the wider community (to have direct and indirect beneficiaries) and to be an indigenous effort (Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:3). CBT should ultimately serve to break the dependency patterns and facilitate holistic development of disadvantaged community/individuals, in that ‘CBT development is seen as a way to promote holistic community development which encapsulates empowerment, self-reliance, social justice, sustainability, freedom and so on’ (Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:3).

3. Understanding AD and CBT

The concept of AD was established in 1982 with the following intention: ‘ … to recuperate small centers which were destroyed after the earthquake’ of 1976 that devastated large parts of various locations in the north-east Italian region of Friuli Venezia Giulia (Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:4). The AD model was then successively ‘engineered by Giancarlo Dall’Ara’ (Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:4). In 2011 it was proposed that the new formula for accommodation, AD, was ‘gradually growing in popularity’ (Confalonieri, Citation2011:685). For example, in Italy in 2004 ‘there were 60 tourist accommodation structures that proposed special forms of widespread accommodation’ (Avram & Zarrilli, Citation2012:35). By 2011, 11 Italian Regions had issued specific guidelines in relation to AD (Confalonieri, Citation2011:686). At an international level, recent interest in the AD model has been demonstrated by various countries and ‘A trademark has been registered by the Italian National Association of Alberghi Diffusi and is valid at European level’ (Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:10). Despite international acclaim for the AD model, it ‘ … is still little researched in the economic and managerial literature and not adequately recognised by local decision makers’ (Quattrociocchi & Montella, Citation2013:119). This article hopes to contribute to this gap specifically in the South African context where the model seems to be completely unknown.

Inasmuch as AD is about local development and visitor experience,

The Italian albergo diffuso [AD] confirms the idea of a tourist development that respects the territory, besides the fact that it successfully meets the market requirements. It perfectly fits the model of tourist sustainable development, based on local resources, careful with the quality of products and processes, aware of how important it is to preserve and enhance the local identity. (Avram & Zarrilli, Citation2012:35)

Table 1. Comparison between forms of hospitality.

Beside these specific differences (as presented in ), the advantages of the AD model compared with traditional types of hospitality may be listed as follows (from Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:5):

AD generates a high-quality tourist product, expression of local areas and territories without generating negative environmental impacts (nothing new has to be built, existing houses must be restored and networked).

AD helps to develop and network the local tourist supply.

AD increases sustainable tourist development in internal areas, in villages and hamlets and in historical centres, in the off-beaten track areas, increasing the supply in the tourist market.

AD contributes to preventing the abandonment of the historical centres.

Various conditions are suggested for the establishment of AD, such as that AD should be an indigenous effort, should include a single management unit and should remain within a specific number and location of rooms, and there is a population which is interested in working together and providing a tourism service (Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d:6).

It is proposed in this article that these conditions should be read flexibly, because each specific context may have its own different requirements and conditions. The given guidelines, however, provide a proper indication of the framework and realities that should be present in developing AD.

AD goes beyond the mere ‘hotel’ development concept because AD:

… is more than just a new hotel or a renovation project. It is a synthesis of different updated concepts. It was a chance to protect and revitalise a whole local system from economical, social, cultural and energetic points of view, in an affordable manner. (Tagliabue et al., Citation2012:1067)

Although not always obligatory, AD seems to require a higher level of investment compared with CBT. Therefore, when AD includes the restoration/renewal of historical buildings, large amounts of investment could be necessary (see Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:8); whereas when specific restorations are not needed and the present buildings are regarded as satisfactory, the level of investment required could dramatically decrease and not need ‘ … green field investments or any other type of construction’ (Dropulić et al., Citation2008:610).

The community-based approach to development seems important since ‘Community based planning is a form of planning that focuses on the grass roots level of the community as the alternative to a top down approach’ (Harwood, Citation2010:1910). Both CBT and AD seem to have and remain within a community-based development approach. AD, the same as already proposed for CBT, should have an indigenous and cooperative origin (Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:6). In addition, both AD and CBT need to have facilitative entities to succeed (see Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:5 for CBT; and Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:6 for AD). From an environmental perspective, the same applies to CBT that could use local houses such as in the homestay type of CBT (Jamal et al., Citation2011:5);Footnote1 AD may avoid the need to build new infrastructure (restoration/renewal may, however, be necessary) as already existing buildings/infrastructure are used (Tagliabue et al., Citation2012:1067). Links between AD studies and those of other forms of tourism are evident, such as the proposal to link AD with ecotourism since AD ‘perfectly fits the model of tourist sustainable development’ (Avram & Zarrilli, Citation2012:35). Interestingly, the AD model is perceived as a possible tourism model in developing countries (see GDA, Citationn.d.).

Tourism in South Africa was indicated as a possible tool for local economic development more than a decade ago (Nel & Binns, Citation2002:252; see also Rogerson, Citation2013:19). However, particularly in disadvantaged rural contexts, the small, medium and micro enterprises (SMME) suffer various difficulties and remain of ‘survivalist character’ (Ndabeni & Rogerson, Citation2005:132). The same authors (Ndabeni & Rogerson, Citation2005:137) indicate the absence of ‘business organisations in the tourism SMME’ despite their possible positive contribution to tourism SMME development; specific organisations thus need to be encouraged. CBT organisation is also seen as relevant in properly supporting CBT development (Giampiccoli et al., Citation2014). In this context the need for a proper tourism organisation at the community level must be understood, and should be included in the general perspective on tourism development that has shifted its orientation so that tourism as ‘an alternative driver for LED in South Africa re-focuses our attention on planning and creating localities as centres for consumption’ (Rogerson, Citation2013:10). However, comments on the report from the World Travel and Tourism Council on South Africa identified ‘ … the failure of the tourism sector to create jobs and develop small businesses’ (Elliott & Boshoff, Citation2005:91).

While government entities are regarded as fundamental (and need to be capacitated in this respect) to foster tourism development, there is ‘the need for greater understanding at local level of the different forms of tourism which can be drivers of local economic development’ (Rogerson, Citation2013:20). As such, there exists a need to discover a solution for tourism development that could enhance the role of tourism in local development within a community-wide approach. AD and CBT forms of tourism may well contribute to the tourism potential in such development.

4. Models of CBT and AD: Possible relationships and roles

This section investigates the possible relationship between, and roles of, AD and CBT by looking at some specific models. It is not the aim of this article to propose and investigate all ranges of CBT models present in the literature. However, as examples these models include the issues of CBT approach (bottom-up or top-down) (Zapata et al., Citation2011:740), listing various CBT business models (Calanog et al., Citation2012:303) or being based on the level of involvement and intensity of participation of community members in the CBT entity (Häusler & Strasdas, Citation2003:26; see also Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013, Citation2014 in relation to CBT model development options). On the other hand, the novelty of AD means that only a few models have been suggested to date. In AD, the legal entity established may be one of several different types; it: ‘can be either a single entrepreneur, a cooperative, or any other most suitable form of productive association’ (Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:6). It appears that three models of AD have been proposed to date. presents the CBT and AD models.

Table 2. General outline of CBT and AD venture models.

There are other possible interpretations based on specific case-by-case factors, and by avoiding a rigid approach (thereby exploiting the possible flexibility of the models themselves) it is possible to establish similarities between AD and CBT models using .

AD model 1 seems to open up the possibility of an external investor (although the investor could also be a local person) in controlling AD. In addition, AD will be owned by a single person/company, without the distributive ownership present in AD models 2 and 3. (Re-)Distribution patterns are central to the CBT concept. On the other hand, CBT model 1, being a single accommodation facility, goes against the concept of AD that aims for a system with multiple accommodations. CBT model 3 offers the possibility of external control (similar to AD model 1) of the tourism venture. The models that share a major commonality therefore seem to be AD models 2 and 3, with CBT model 2 and (partly) CBT model 3 depending on the type of partnership and type of accommodation infrastructure (single or multiple structures). In this case, when CBT model 3 makes use of an ‘external’ partnership (when the external partner does not share the CBT entities itself but shares external CBT services and needs such as marketing) (see Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:11), the similarity with AD models 2 and 3 would be more obvious.

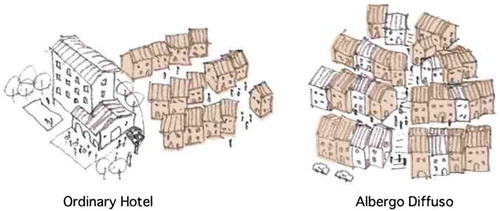

AD’s difference from an ordinary hotel can be seen in where a stand-alone (white) ordinary hotel is replaced by a number of (white) houses representing, all together, the AD model. should be understood in the context where AD is not isolated from local reality but, on the contrary, often

acts as the most relevant stakeholder on the territory stimulating the local existing and potential entrepreneurs in creating new businesses associated with the increased tourist demand that it brings, mainly in the most traditional sectors such as local gastronomy and handicrafts. (Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:3; see also Racine, Citation2012)

instead shows (from Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:6) a CBT model that describes multiple (accommodation) ventures working together under an umbrella organisation. In addition, the model illustrates how the CBT accommodation entity is not isolated (similar to that of AD) from the local reality.

Figure 2. CBT multiple micro and small enterprises model.

CBT and AD are thus inherently linked to the local context and both are supposed to be, as much as is possible with their different capacities and resources, a catalytic entity in local development. Both CBT and AD base their development and sustainability on the local community, resources and general context. While their backgrounds differ, they both aim to foster local development: CBT operates more from the perspective of disadvantaged community members, while AD, by reviving a specific location (e.g. renewing old houses), aims to revive the general local contexts. Although the tourist market’s general traits may be associated with the new tourists looking for ‘authenticity’, uniqueness, ‘living’ and learning the local community lifestyle and so on, AD seems (but is not necessarily) more oriented towards the high-end market with high-quality products and services, and is often associated with a greater need for investment, capacity and resources in general. CBT might possibly be (but is not necessarily) associated with lower level services and infrastructure. CBT could also be informal (Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:2) and therefore require less investment, capacity and resources. This is not to say, however, that CBT should be seen as an inferior type of tourism. Any perception of inferiority of the CBT products (Auala, Citation2012:65) should be countered with appropriate CBT management standards and recognition by specific tourism bodies. This could also enhance the possible relation between CBT and AD. In developing countries where the CBT is often used as a development tool in disadvantaged contexts, AD could contribute through a specific relationship to CBT enhancement, while at the same time advancing and promoting AD itself.

A specific link between AD and the cooperative concepts has been indicated (see Marquardt, Citationn.d.:37). AD being advocated as a cooperative should also include benefits to the wider community, because of the seventh principle of a cooperative (see International Co-operative Alliance, Citationn.d.). These matters were noted when indicating that AD ‘encourages one or more homeowners to participate in an organisation that is usually a cooperative and supports the development of small businesses working in traditional sectors like handicrafts and food preparation’ (Racine, Citation2012). Many AD cooperatives are extant, such as the La Conca Amatriciana that started in 2001 (Dichter & Dall'Ara, Citationn.d.:8), the AD cooperative of Ornica in the Italian Brembana Valley (Pesenti, Citation2012:37) or the Cooperativa Albergo Diffuso Comeglians that since 1999 has aimed to promote the mountain where it is based (Coop. Albergo Diffuso Comeglians, Citationn.d.). CBT can be also based (and in fact should be based) on collective management systems such as a cooperative (see Mohamad & Hamzah, Citation2013; Mtapuri & Giampiccoli, Citation2013:3).

In the tourism sector, a collective form of entrepreneurship such as a cooperative has not yet been properly recognised as it should be: as a vehicle for resolving socio-economic difficulties (Verma, Citation2008). It also relevant to mention that ‘The cooperative entrepreneurship is now considered a model of community growth’ (Tewari, Citation2011:8986). The role and the value of cooperative and social enterprises are under-rated, even if ‘they often achieve economic and social outcomes that are better than those achieved by conventional enterprises and public institutions’ (Borzaga et al., Citation2009:3). Cooperatives, despite difficulties, are possible in different ‘social, economic, political and cultural settings’ (Ife, Citation2002:135). At the same time, new types of social entrepreneurs and associations could lean towards the establishment of an AD system as an entrepreneurial strategy. While a cooperative is usually a legal entity, in AD this should be seen as compulsory, and other legal entities can be used in the ownership and management of AD. It should be noted that the South African Government recognises the value of cooperative ventures and that tourism is seen as one possible sector (DTI, Citation2012:13–14 and 37).

These various common enveloping characteristics of AD and CBT underpin the possible linkage or collaboration between AD and CBT entities that might be possible, for example in a small town context. However, while AD and CBT collaboration should not be limited to villages or small towns and their possible relationship should be facilitated and promoted in any context, it is probable that villages and small towns will offer a favourable substratum on which they can establish this collaborative effort. Many villages or small towns in South Africa have a depressed or stagnant economy; strong migration trends and tourism are regarded as possible solutions to revive these locations’ economies. Examples of this trend would be a location becoming available with the demise of mining and connected industries (Nel & Binns, Citation2002:253; Binns & Nel, Citation2003:41) or proposals for tourism as a development tool in the ‘stagnant economies of small Karoo towns’ (Maguire, Citationn.d.:1). Small towns are perceived as important nuclei to contribute to the development of the local area (Atkinson, Citation2008:5). Thus, ‘The argument for a small town renewal approach is based on the role of small towns in Africa as a vehicle for growing the local economy and as a basis for sustainable rural development’ (Xuza, Citation2005:90) and, beyond agriculture, tourism may well have a relevant role to play in such a renewal (Xuza, Citation2005:94). At the same time, the original reason AD was linked to village or small town renewal and revitalisation does not seem to preclude the adoption of the AD model of hospitality in locations that do not necessarily need revitalisation. In this case, the adoption of (or shift to) the AD model could serve to enhance (and perhaps rejuvenate) the significance for tourism which might already exist, while at the same time enhancing the sense of community and its cohesion. In this case, the AD function should be regarded as an enhancer of an already present and satisfactory tourism context, increasing its value and the community involvement in it.

Based on this discussion, this article advocates that a linkage, collaboration or association between AD and CBT entities should be favourably regarded. Four main models of cooperation/partnership are suggested:

External collaboration model. AD and CBT entities collaborate by working on, or having, some kind of common structure such as information and/or marketing offices. Besides the possible resource savings, the common structures/offices can market a wider range of attractions and services and increase the target market range.

Service collaboration model. AD uses some specific CBT service/products (or vice versa). In this case, for example, AD can reserve a lunch for its tourists in a CBT food outlet, or AD can reserve a CBT walking trail in the rural surrounding area. The opposite approach where CBT uses AD services facilities is also possible (despite the possibly more disadvantaged position of the CBT venture) because it is not the CBT that pays for the service, but the tourists. Therefore, the CBT can also reserve AD services and products for its tourists for as much as they are willing to pay.

Partial association model. AD and CBT entities become more formally related. When conditions are suitable, some members of CBT can formally become part of AD (or vice versa).

Full association model. The full AD and CBT entities become a single entity; for example, by forming an umbrella structure with AD and CBT membership (with single members or as a single CBT and AD entity) or by making CBT and AD one legal entity itself.

Each model must be understood flexibly and can work in unison with or in parallel with other model(s). For example, the external collaboration and service collaboration models may exist at the same time. In any of these models it is possible that a required similar level of quality standard might be needed. In this case, collaboration and facilitation could assist with achieving these standards in both AD and CBT. In addition, the partial association and full association models could serve to collaboratively coordinate and manage the associated members and allow tourists to benefit from a larger basket of services, products and attractions under the same tourism entity.

It must be recognised that an AD entity might possess superior capacity, resources and influence compared with a CBT entity. However, this advantage may also be valuable to CBT if the collaboration is properly advanced and managed. AD will be able to market extra attractions in the rural/township area (attractions that will be difficult for the AD model to have in its own portfolio without the CBT entity). This collaboration also guarantees AD for the quality and standard of the CBT products and services. Secondly, by involving the CBT entity more local people may well come to understand the benefit of tourism, enhancing the possibility of making the area more secure for tourists. Thirdly, although this should not be seen in the idealistic sense, the collaboration amongst AD and CBT could contribute to building more trust and positive relationships between different sections of the population in South Africa.

5. Conclusion

This article aimed to initiate the topic of possible relationships between AD and CBT and to introduce the topic of AD in the South African context. The aim has not been to portray CBT and AD as similar concepts, but to offer some background reasoning as regards tourist market trends, the value and input of local actors, the facilitative role of government, the avoidable need to build new infrastructure/facilities, and the role of AD and CBT in local context development as well as to illustrate certain common denominators between AD and CBT. In particular, using models from AD and CBT, the article has identified some similar characteristics of implementation and operationalisation of CBT and AD, such as the spatial distribution of facilities and a management system that in both cases could be based on a collective management system such as a cooperative one.

This article has found that AD and CBT characteristics may be instrumental in shaping possible collaborative efforts amongst CBT and AD enterprises. As such, the linkages between CBT and AD entities could serve to increase their attractiveness to tourists (as the attraction/service portfolios of both CBT and AD are enlarged) and at the same time to revive or augment the local tourism development. Together, AD and CBT could contribute to greater enhancement of the tourism sector within the framework of local holistic development that embraces more segments of society. Consequently, this article’s contribution is related to the illustration of the potential that AD itself, and particularly AD and CBT collaboration, can offer for local (entire) community development. This is particularly true in countries such as South Africa where many small towns or villages are suffering economic depression; therefore, novel tourism forms can be proposed as a possible new development strategy. The article adds value to the debate on tourism’s role in local development because it proposes possible solutions in this respect.

Certainly, more research is needed to explore AD and its role in local economic development. This is particularly true in the South African context where more research into and recognition of the AD model, and its possible association with CBT, could serve to establish a synergy and cooperation between two tourism development models that are, despite their differences, locally based, aimed at local development and together could contribute to the revival/rejuvenation of townships, villages and small towns in a holistic way, including both the ‘high end’ and more CBT-oriented market, because together they should satisfy the tourist market and positively impact on more levels of the community, instead of benefiting a specific community group.

Notes

1 Note, however, that CBT and homestays are not always necessarily similar in all their characteristics (see Suansri, Citation2003:18 for the relationship between homestays and CBT).

References

- Asker, S, Boronyak, L, Carrard, N & Paddon, M, 2010. Effective community based tourism: A best practice manual. APEC Tourism Working Group. Griffith University, Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre.

- Atkinson, D, 2008. Inequality and economic marginalisation. Creating access to economic opportunities in small and medium towns. Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies. http://www.tips.org.za/files/u65/economic_opportunities_in_small_towns_-_atkinson.pdf Accessed 15 March 2015.

- Auala, S, 2012. Local residents’ perceptions of community-based tourism (CBT) at Twyfelfontein Uibasen Conservancy in Namibia. Journal for Development and Leadership 1(1), 63–74.

- Avram, M, & Zarrilli, L, 2012. The Italian model of “Albergo Diffuso”: A possible way to preserve the traditional heritage and to encourage the sustainable development of the Apuseni Nature Park. Journal of Tourism and Geo Sites 9(1), 32–42.

- Beeton, S, 2006. Community development through tourism. Landlinks Press, Melbourne.

- Binns, T & Nel, E, 2003. The village in a game park: Local response to the demise of coal mining in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Economic Geography 79(1), 41–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2003.tb00201.x

- Boonzaaier, CC & Philip, L, 2007. Community-based tourism and its potential to improve living conditions among the Hananwa of Blouberg (Limpopo Province), with particular reference to catering services during winter. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences 35, 26–38.

- Borzaga, C, Depedri, S & Tortia, E, 2009. The role of cooperative and social enterprises: A multifaceted approach for an economic pluralism. Euricse Working Papers, N. 000 | 09.

- Bulgarelli, G, n.d. The “Albergo Diffuso” a way to develop tourism by mean of innovation and tradition. https://www.academia.edu/334034/The_Albergo_Diffuso_A_way_to_develop_tourism_by_mean_of_innovation_and_tradition Accessed 13 March 2015.

- Calanog, LA, Reyes, DPT & Eugenio, VF, 2012. Making ecotourism work. A manual on establishing community-based ecotourism enterprise (CBEE) in the Philippines. Japan International Cooperation Agency, Makati City.

- Choi, HC & Sirakaya, E, 2006. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism Management 27, 1274–1289. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2005.05.018

- Confalonieri, M, 2011. A typical Italian phenomenon: The “albergo diffuso”. Tourism Management 32, 685–687. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.022

- Coop. Albergo Diffuso Comeglians, n.d. Chi Siamo. http://www.albergodiffuso.it/chisiamo.aspx?id=5 Accessed 15 March 2015.

- Dichter, G & Dall'Ara, G, n.d. Albergo diffuso developing tourism through innovation and tradition. IDEASS – Innovation by Development and South-South Cooperation. http://www.ideassonline.org/public/pdf/br_47_01.pdf Accessed 14 March 2015.

- Dolezal, C. 2011. Community-based tourism in Thailand: (Dis-)illusions of authenticity and the necessity for dynamic concepts of culture and power. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies 4(1), 129–38.

- Dropulić, M, Krajnović, A & Ružić, P, 2008. Albergo diffuso hotels: A solution to sustainable development of tourism. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Organizational Science Development. Knowledge for Sustainable Development, 19–21 March, Portorož, Slovenia.

- DTI (Department of Trade and Industry), 2012. Integrated Strategy on the Development and Promotion of Co-operatives. Promoting an Integrated Co-operative Sector in South Africa, 2012–2022. Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria.

- Elliott, R & Boshoff, C, 2005. The utilisation of the Internet to market small tourism businesses. South African Journal of Business Management 36(4), 91–104.

- Ellis, S & Sheridan, L, 2014. A critical reflection on the role of stakeholders in sustainable tourism development in least-developed countries. Tourism Planning & Development 11(4), 467–71. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2014.894558

- Fiorello, A & Bo, D, 2012. Community-based ecotourism to meet the new tourist's expectations: An exploratory study. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 21(7), 758–78. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2012.624293

- Gartner, C & Cukier, J, 2012. Is tourism employment a sufficient mechanism for poverty reduction? A case study from Nkhata Bay, Malawi. Current Issues in Tourism 15(6), 545–62. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2011.629719

- GDA (Giancarlo Dall’Ara Consulenze e progetti di marketing), n.d. Benvenuto nel sito ufficiale degli alberghi diffuse. http://www.albergodiffuso.com Accessed 14 March 2015.

- George, BP, Nedelea, A & Antony, M, 2007. The business of community based tourism: A multi-stakeholder approach. Journal of Tourism Research, Tourism Issues 3, 1–19.

- Giampiccoli, A, & Saayman, M, 2014. A conceptualisation of alternative forms of tourism in relation to community development. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(27 P3), 1667.

- Giampiccoli, A, Saayman, M & Jugmohan, S, 2014. Developing community-based tourism in South Africa: Addressing the missing link. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance 20(3:2), 1139–61.

- Harwood, S, 2010. Planning for community based tourism in a remote location. Sustainability 2, 1909–23. doi: 10.3390/su2071909

- Häusler, N & Strasdas, W, 2003. Training manual for community-based tourism. InWEnt – Capacity Building International, Zschortau.

- Ife, J, 2002. Community development: Community-based alternative in the age of globalisation. Pearson Education, Sydney.

- International Co-operative Alliance, n.d. What is a co-operative? http://ica.coop/en/what-co-operative Accessed 15 March 2015.

- Jamal, SA, Othman, N’A & Nik Muhammad, NM, 2011. Tourist perceived value in a community-based homestay visit: An investigation into the functional and experiential aspect of value. Journal of Vacation Marketing 17(1), 5–15. doi: 10.1177/1356766710391130

- Liçaj, B, 2014. Albergo Diffuso: Developing tourism through innovation and tradition: The case of Albania. Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal IV(III), 84–91.

- Maguire, JM, n.d. Tourism and the heritage assets of the Karoo outback. http://www.karoofoundation.co.za/images/GRT%20confrence/Judy_Maguire_paper_-_TOURISM_AND_THE_HERITAGE_ASSETS_OF_THE_KAROO.pdf Accessed 15 March 2015.

- Malatji, MI & Mtapuri, O, 2012. Can community based tourism enterprises alleviate poverty? Toward a new organization. Tourism Review International 16(1), 1–14. doi: 10.3727/154427212X13369577826825

- Marquardt, D, n.d. Modello-tipo di cooperativa ID-Coop (Coop-Toolkit) – Versione regioni italiane Deliverable D.4.02, WP4. Progetto Interreg IV Italia-Austria ID-Coop, N.5324. http://www.id-coop.eu/en/Documents/ID_Coop_Toolkit_IT_FINAL.pdf Accessed 15 March 2015.

- Mearns, KF & Lukhele, SE, 2015. Addressing the operational challenges of community-based tourism in Swaziland. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 4(1), 1–13.

- Mohamad, NH & Hamzah, A, 2013. Tourism cooperative for scaling up community-based tourism. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 5(4), 315–28. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-03-2013-0017

- Monge, F, Cattaneo, D & Scilla, A, 2015. The widespread hotel: New hotel model for business tourist. Journal of Investment and Management 4(1–1), 69–76.

- Mtapuri, O & Giampiccoli, A, 2013. Interrogating the role of the state and nonstate actors in community-based tourism ventures: Toward a model for spreading the benefits to the wider community. South African Geographical Journal 95(1), 1–15. doi: 10.1080/03736245.2013.805078

- Mtapuri, O & Giampiccoli, A, 2014. Towards a comprehensive model of community-based tourism development. South African Geographical Journal 98(1), 1–15.

- Naguran, R, 1999. Community based tourism in KwaZulu Natal: Some conceptual issues. In Reid, D (Ed.), Ecotourism development in Eastern and Southern Africa. University of Guelph, Ontario. Weaver Press, Harare.

- Ndabeni, L & Rogerson, CM, 2005. Entrepreneurship in rural tourism: The challenges of South Africa's Wild Coast. Africa Insight 35(4), 130–41.

- Ndlovu, N & Rogerson, CM, 2004. The local economic impacts of rural community-based tourism in Eastern Cape. In Rogerson, CM & Visser, G (Eds.), Tourism and development issues in contemporary South Africa. Africa Institute of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Nel, E & Binns, T, 2002. Decline and response in South Africa’s free state goldfields. Local economic development in Matjhabeng. IDPR 24(3), 249–69.

- Pesenti, M, 2012. Cooperativa e albergo diffuso, a Ornica la ricetta vincente per ripopolare la valle. L’Eco di Bergamo, Mercoledì 19 Settembre 2012, p. 37.

- Quattrociocchi, B & Montella, MM, 2013. L’albergo diffuso: un’innovazione imprenditoriale per lo sviluppo sostenibile del turismo. XXV Convegno annuale di Sinergie, L’innovazione per la competitività delle imprese, 24–25 Ottobre 2013, Università Politecnica delle Marche (Ancona). Referred Electronic Conference Proceeding, ISBN 978-88-907394-3-9. doi:10.7433/SRECP.2013.08

- Racine, A, 2012. Albergo diffuso: An alternative form of hospitality. http://tourismintelligence.ca/2012/01/12/albergo-diffuso-an-alternative-form-of-hospitality/ Accessed 15 March 2015.

- Rogerson, CM, 2004. Tourism, small firm development and empowerment. In Thomas, R (Ed.), Small firms in tourism: International perspectives. Elsevier Science, St. Louis, MO.

- Rogerson, CM, 2013. Tourism and local development in South Africa: Challenging local governments. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance 2, 9–23.

- Saayman, M, Rossouw, R & Krugell, W, 2012. The impact of tourism on poverty in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 29(3), 462–87. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2012.706041

- Sin, HL & Minca, C, 2014. Touring responsibility: The trouble with ‘going local’ in community-based tourism in Thailand. Geoforum 51, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.004

- Suansri, P, 2003. Community based tourism handbook. Responsible Ecological Social Tour (REST), Bangkok.

- Tagliabue, LC, Leonforte, F & Compostella, J, 2012. Renovation of an UNESCO heritage settlement in southern Italy: ASHP and BIPV for a “Spread Hotel” project. Energy Procedia 30, 1060–68. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2012.11.119

- Tewari, DD, 2011. Wealth creation through mass capital mobilization through a cooperative enterprise model: Some lessons for transplanting the Indian experience in South Africa. African Journal of Business Management 5(22), 8980–89.

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization), 2014. UNWTO. Tourism Highlights. World Tourism Organization, Madrid.

- Vallone, C, Orlandini, P & Cecchetti, R, 2013. Sustainability and innovation in tourism services: The Albergo Diffuso case study. Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences 1(2), 21–34.

- Vallone, C & Veglio, V, 2013. “Albergo Diffuso” and customer satisfaction: A quality services analysis. Conference Proceedings 16th Toulon-Verona Conference “Excellence in Service”, 29–30 August, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- Verma, SK, 2008. Cooperatives and Tourism: An Asian perspective. National Cooperative Union of India. http://torc.linkbc.ca/torc/downs1/india%20cooperatives.pdf.

- Xuza, PHL, 2005. Renewal of small town economies. The case of Alice, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Africa Insight 35(4), 90–96.

- Yang, X & Hung, K 2014. Poverty alleviation via tourism cooperatives in China: The story of Yuhu. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 26(6), 879–906. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-02-2013-0085

- Zapata, MJ, Hall, MC, Lindo, P & Vanderschaeghe, M, 2011. Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Current Issues in Tourism 14(8), 725–49. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2011.559200