ABSTRACT

This article presents findings of a mixed-methods research study undertaken to evaluate the sustainability of the social sector of the Expanded Public Works Programme as a poverty alleviation strategy targeting women, youth and persons with disabilities. The study revealed that the social sector of the Expanded Public Works Programme has made a contribution to poverty alleviation, but may not be sustainable in the long term because of its reliance on volunteers, who receive a stipend. The programme is also limited by the fact that its implementation is focused mainly on one ethnic group. The article makes recommendations which may strengthen the social sector of the Expanded Public Works Programme to facilitate its sustainability.

1. Introduction

In South Africa poverty is a result of economic, environmental, social and political factors (Patel, Citation2005:52). The South African government thus introduced various strategies and programmes to alleviate poverty among vulnerable groups like women, youth and persons with disabilities.

Social work, as a profession, has the responsibility of shaping, selecting and influencing social policy (Levy as cited in Schneider & Netting, Citation1999:351). This is also emphasised by the International Federation of Social Work (Citation2014:6), who state that ‘social development activity is well-recognised throughout Africa, delivered by a range of agencies and professionals, including social development and social work practitioners’. The International Federation of Social Work further states that:

Social workers, educators and social development practitioners have worked together on The Global Agenda (for social work and social development) theme across the region. Two conferences drew practitioners and educators together, raising awareness of the Global Agenda and assisting the development of a regional overview on promoting social and economic equalities. (Citation2014:6)

The aforementioned clearly indicates that social workers in the world, and specifically in Africa, have a responsibility towards people who are marginalised by advocating for policies which will empower them. The reality is that most people who are marginalised, such as women, people with disabilities, youth, children and rural communities, are poor (Patel, Citation2005:52). Furthermore, according to the Southern African Regional Poverty Network (Citation2005:170), women, youth, unemployed people, persons with disabilities, the aged, child-headed households and people living with HIV and AIDS have all been identified as falling into the category of vulnerable groups.

In South Africa, approximately 51% of all South Africans live in households that fall below the poverty threshold (Statistics South Africa, Citation2011:29). The notion of women being more affected by poverty is confirmed by Statistics South Africa (Citation2010), according to whom all South African employees who were in paid employment had median monthly earnings of R2800 (US$168.87), the median monthly earnings for men being R3033 (US$182.93). This is higher than the median monthly earnings for women, which was R2340 (US$141.13). Women in paid employment therefore earn only 77.1% of what men earn.

One of the South African government’s strategies to deal with poverty and vulnerability among certain groups was the introduction of the National Public Works Programme in 1994 (Zegeye & Maxted, Citation2002:90). The main aims of this programme were poverty alleviation, job creation, income generation and empowerment. As an extension of the National Public Works Programme, the government introduced the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) in 2004. This programme was formally announced by the former state president of the Republic of South Africa, TM Mbeki, as one of the efforts of the South African government to reduce poverty through the alleviation and reduction of unemployment (Department of Social Development et al., Citation2004:7). The initiative is described as ‘a nationwide program which will draw significant numbers of the unemployed into productive work, so that workers gain skills while they work, and increase their capacity to earn an income’ (Department of Social Development et al., Citation2004:7). The EPWP targets vulnerable groups, so that they can be economically active. Women, youth and persons with disabilities are the official targets for Public Works Programmes in South Africa. In each programme, 40% should be women, 20% youth and 2% persons with disabilities (McCord, Citation2003:16).

2. Theoretical framework

The social development approach is appropriate in the context of this study on the EPWP because it focuses on promoting the welfare and well-being of people, including economic development. This is relevant to the EPWP because it stresses the provision of jobs, development of the economy and skills (Department of Social Development et al., Citation2004). Another element of the concept social development which is emphasised by Lombard (Citation2007:299) is the fact that social development cuts across different sectors such as health, education, economic development and welfare services. This inter-sectoral relationship is also underpinned in the social sector of the EPWP, as it is being implemented by different government departments, namely, the Departments of Social Development, of Health and of Education (Departments of Social Development et al., Citation2004:9).

The following discusses the principles of social development, which clearly elucidate its link with the EPWP (Midgley, Citation1995:26).

2.1. Social development is linked to economic development

Social development interventions should lead to improvements in people’s economic situations. In terms of this characteristic, no meaningful social development can be assumed to have taken place if people do not benefit economically. Economic development is also emphasised in the EPWP, as the programme seeks to create jobs for the unemployed people. This is a clear link between social and economic development.

2.2. Social development is interdisciplinary

The social development approach incorporates various disciplines such as social work, politics and economics in the social sciences. This is also applicable to the EPWP, which is implemented by various government departments that focus on various disciplines; for example, social development, health, education, transport and public works.

The social sector of the EPWP, which is the focus of this study, is also interdisciplinary, focusing on social services, education and health (Department of Social Development et al., Citation2004).

2.3. Social development involves a process which leads to positive change

In implementing social development, there should always be positive change in the lives of beneficiaries or communities. This characteristic is specifically applicable to the EPWP, as the programme is planned in such a manner that by the end of it individuals and communities would have undergone positive change, by gaining skills and accessing employment opportunities which will empower them.

2.4. The change process in social development is progressive

Change that is brought about by social development interventions should always lead to improvement in people, because all human beings have the potential to improve. This is also the case with the EPWP, because it seeks to empower people by providing skills and creating job opportunities.

2.5. The process of social development is interventionist

Improvement in the welfare or living conditions of people will not happen spontaneously or naturally. There is always a need for intervention to bring about the positive change in people’s living conditions. That is why it is important that conscious efforts should be made to bring about positive change.

The EPWP is an example of one of the conscious and constructive efforts on the part of the South African government to bring improvement to the lives of citizens, especially those that are marginalised and vulnerable.

2.6. The goals in social development are carried out through various strategies, which are linked to economic development

The various strategies in the context of social development can be at an individual, community or government level.

At an individual level, social development can be achieved by encouraging entrepreneurship or small income-generating businesses for the poor, or enhancing individuals’ social functioning. Here social workers can play a role by offering individual interventions to remove barriers that prevent people from functioning well (Midgley, Citation1995:112).

At a community level, community development projects can be undertaken by communities to improve their lives, or specific issues such as women development or gender issues may be addressed to improve the lives of women. This is in line with the EPWP because it also targets communities or specific groups of people such as women, youth and persons with disabilities as beneficiaries.

2.7. Social development is inclusive and universalistic

Social development is broad and encompasses all members of the society.

Much as the poor and vulnerable people are a major target of social development interventions, this intervention takes place within a wider universalistic context that promotes the welfare of all people in a region, community or society (Midgley, Citation1995:27). Social development thus focuses on specific wider and universalistic spatial settings; for example, rural areas, specific regions, cities or countries.

2.8. Social development promotes social welfare

Social development promotes the well-being of people and communities by creating opportunities and managing the problems that people have. This means that the ultimate outcome of all interventions should be the well-being of people by meeting their needs and helping them to solve their problems. The EPWP also promotes the social welfare of people by meeting their needs through job creation and skills development.

The social development approach thus looks for solutions which empower people and communities, and does not adopt a remedial approach (Twikirize et al., Citation2013).

3. Poverty and the Expanded Public Works Programme in South Arica

The issue of poverty alleviation is a global concern. This is backed by the fact that the first Millennium Development Goal is to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger (Republic of South Africa, Citation2010). The activities of the EPWP programme to reduce poverty therefore support Goal 1 of the Millennium Development Goals.

Different authors define poverty from different viewpoints. Zegeye & Maxted (Citation2002) state that the 1990 World Development Report defines poverty as the ‘inability to attain a minimal standard of living measured in terms of basic consumption needs or income required to satisfy them’. This means that, in order to avoid poverty, people need an income to buy a minimum standard of food and other basic necessities. According to Swanepoel & De Beer (Citation2006), relative poverty refers to people whose basic needs are met, but who, in terms of their social environment, still experience some disadvantages. No matter which definition of poverty is utilised, there is no doubt that poverty is a worldwide problem, and that it is more prevalent in developing countries. This is confirmed by Ferreira & Ravallion (Citation2008), who maintain that absolute poverty and inequality is a bigger problem in developing countries where more than four-fifths of the world’s population lives. They further explain that there is a negative correlation between average levels of inequality and the level of development. This fact is confirmed by the International Labour Organisation, which mentions that 500 million of the poorest people live in Africa (International Labour Organisation, Citation2009).

South Africa is also affected by poverty, although it is classified as an upper-middle-income country. The majority of the country’s citizens live in outright poverty or are vulnerable to becoming poor. The income and wealth distribution is also said to be among the most unequal in the world. According to Woolard (Citation2002), this inequality means that hunger, poverty and overcrowding exist in the midst of wealth. The United Nations Development Programme (Citation2010) also confirms the fact that poverty is one of South Africa’s developmental challenges.

Poverty in South Africa also has a rural bias: 70% of people in rural areas are poor, as opposed to 30% in urban areas (Zegeye & Maxted, Citation2002). The rural bias of poverty is also corroborated by the African National Congress, which states that poverty affects millions of South Africans, the majority of whom live in the rural areas and are women (African National Congress, Citation1994). More recently, Strydom & Tlhojane (Citation2008) have also verified the rural bias of poverty in South Africa by stating that the circumstances of the poor in rural areas in South Africa are worsening because they have no access to resources.

Poverty in South Africa is also linked to inequality. Chen & Syder (Citation2006:14) define inequality as:

the degree to which resources are concentrated: in a situation where everyone has the same amount of resources, there is zero inequality, but where the distribution of resources is unequal and more resources are concentrated within a small sector of the population, there are higher levels of inequality.

This is confirmed by the Taylor committee (cited in Zegeye & Maxted, Citation2002:13), who state that ‘inequality is the unequal opportunities and benefits for individuals or groups within society. This is applicable to both the social and economic aspects, and is influenced by social class, gender, ethnicity and locality’.

South Africa has high levels of inequality. Netshitenzhe (Citation2012) affirms that South Africa has extreme forms of inequality, with a Gini coefficient of 0.68 which is said to be the second highest in the world. Initially, inequality in South Africa was because of the gap in incomes of different racial groups, but the situation has recently changed as blacks have progressed into higher occupations, and also because of the increase in unemployment. Netshitenzhe (Citation2012) maintains that between the years of 1994 and 2004 inequality between the different race groups in South Africa decreased because some black people benefited from other opportunities, and inequality increased within racial groups, especially black Africans. When apartheid ended, the gap between the incomes of the employed and unemployed people was significant and became a major driver of inequality (Zegeye & Maxted, Citation2002). The poorest 40% of South Africans are black, female and rural. This means that there is a gender, racial and rural bias with regards to poverty in South Africa. The issue of inequality in South Africa is also confirmed by the National Planning Commission (Citation2011:1), which maintains that whilst progress has been made in the reduction of poverty, insufficient progress has been made to reduce inequality, because many people are still unemployed and many people in working households live close to the poverty line. Triegaardt (Citation2006:1) also emphasises the issue of inequality, by stating that ‘poverty and inequality have existed in developed and developing countries, and that progress in eliminating these remains elusive’. The author further states that South Africa still remains one of the highest ranked countries in the world in terms of income inequality.

The described inequality situation of South Africa is confirmed by Schenck & Louw (Citation2010:367), who contend that South Africa is both a First World and Third World nation and income inequality is growing fast. They further maintain that the economic growth in South Africa conceals the growing unequal income distribution.

The social sector of the EPWP forms part of the broader EPWP, which also includes the infrastructure sector, the economic sector and the environmental sector. The social sector is executed by three departments in the Gauteng province: social development, education and health. It focuses on home community-based care (HCBC) and early childhood development (ECD).

According to the World Health Organisation, HCBC refers to the delivery of health services by caregivers in the home to promote a person’s maximum level of comfort and health. This includes ensuring that the person has a dignified death (Department of Health, Citation2008:1). According to the Department of Social Development et al. (Citation2004:8), the services of HCBC include the following:

early identification of families in need, orphans and vulnerable children;

addressing the needs of child-headed households;

linking families with poverty alleviation programmes and services in the community;

patient care and support linked to HIV and AIDS and other chronic conditions;

information and education;

patient and family counselling and support;

addressing discrimination against, stigmatisation and disclosures of chronic diseases;

family support; and

involvement in income-generating projects.

ECD includes ‘processes by which children from 0–9 years grow and thrive physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually, morally and socially’ (Department of Education, Citation2001:1). According to the Department of Social Development et al. (Citation2004:12), 23% of existing ECD caregivers have no training while the rest need further training. Most of these sites are also not subsidised, so their sole source of income is from parents, who, in some instances, pay less than R50 per month.

Department of Social Development et al. (Citation2004:12) aim to train 19 800 practitioners over five years. This will increase the ECD practitioners’ capacity to have an income and also contribute to the improvement to the care and learning environment of children. The social sector of the EPWP in Gauteng is delivered in partnership with non-profit organisations.

Public Works Programmes (PWPs) have also been implemented in other countries and in the Southern African region. According to the World Bank (Citation1997:1), PWPs have been a popular policy instrument for poverty alleviation in developing countries. For example, in India these programmes have generated income gains to participants, ranging from seven to 10% (World Bank, Citation1997:2). India is also said to have much experience, dating as far back as 1960, in experimenting with labour-intensive PWPs (Dev, Citation2009:1). One of India’s PWPs is known as the Employment Guarantee Scheme.

Some industrial or western countries have also made use of PWPs as an intervention strategy (Subbarao et al., Citation1997:65). The authors state that some western countries such as Germany used PWPs during the depression years of the 1930s and also during the mid-1950s.

Musekene (Citation2013:333) maintains that the Tunisian and Algerian works programme known as Worksites was developed to combat underdevelopment through the creation of job opportunities. In Algeria, this programme began operating in 1962 as a relief operation.

4. Methodology

Within the context of a mixed-methods research approach the researcher utilised the triangulation mixed-methods research design. This is a design where the researcher utilises quantitative and qualitative methods in the same time frame to best understand the phenomenon being studied. Both qualitative and quantitative methods carried an equal weight (Delport & Fouche, Citation2011:442).

Triangulation contributes to overcoming the limitations which stem from utilising a single method of data collection. Yeasmin & Rahman (Citation2012:154) confirm this by stating that triangulation serves the purpose of getting confirmation of findings through the convergence of different perspectives. The authors further state that social realities are by their nature complex and cannot be understood with the use of a single method of data collection.

The following research question guided the study:

How sustainable is the social sector of the Expanded Public Works Programme to empower women, youth and persons with disabilities?

4.1. Quantitative study

A quantitative study was first conducted, using questionnaires to collect data from officials involved in the implementation of the social sector of the EPWP in Gauteng. A total of 152 respondents were involved in the six districts of the Gauteng province.

The sampling used for the quantitative part of the study was a combination of stratified and systematic random sampling. The three strata in the selection of the sample of officials and implementers of the social sector of the EPWP were the Departments of Social Development, of Education and of Health in Gauteng. Within these three strata, systematic random sampling was used to select respondents in each stratum. One hundred and fifty-two questionnaires were distributed to these respondents.

The quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Programme for Social Sciences (SPSS). The reliability of the questionnaire developed was measured using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The overall reliability of the questionnaire was 0.951, which signifies a high level of reliability because a score closer to one indicates high reliability. Content validity was ensured by having multiple items representing the same concept in the questionnaire.

4.2. Qualitative study

Five focus groups were conducted with beneficiaries of the social sector of the EPWP. The intention was to gather data on the beneficiaries’ perceptions and experiences of the programme as a poverty alleviation strategy.

The sampling method used was a combination of purposive and availability sampling. The strata for the study were women, youth and persons with disabilities who were beneficiaries of the social sector of the EPWP in Gauteng, and the sub-strata were the urban and rural areas in the Gauteng province. Thirty-six participants were involved in five focus groups.

Focus group interviews were carried out with only women and youth who are beneficiaries of the social sector of the EPWP. Persons with disabilities did not form part of the focus groups because the departments involved in the social sector of the EPWP had not met the target of recruiting 2% of people with disabilities. presents a summary of the focus groups.

Table 1. Focus group summary.

A total of 36 participants were involved in five focus groups, of which three represented the youth and two represented women. The participants were from rural-based communities and urban-based communities. There were no persons with disabilities in the focus group discussions because, although they are targeted beneficiaries of the programme, the departments involved in the social sector of the EPWP in Gauteng had not recruited any to participate.

The researcher analysed the qualitative data following the procedure described by Cresswell (cited by De Vos, Citation2005:336):

The focus group interviews were recorded and documented. The data collected was managed in such a way that it was retrievable. The researcher created an inventory of all the data collected. Each focus group was properly labelled using dates, names of places, and description of participants. The interviews were transcribed and translated. Based on a thorough analysis of each transcript, categories, themes and sub-themes were identified. Tables, diagrams or figures and descriptions were used to present information.

4.3. Ethical considerations

The Departments of Social Development, of Health and of Education in Gauteng granted permission for the research to be conducted. Individual respondents also gave their consent to participate in the study by signing an ‘informed consent’ letter. Other ethical considerations included avoidance of harm, the avoidance of deception, and the assurance of confidentiality and anonymity.

5. Results

5.1. Districts in which the social sector of the EPWP is implemented

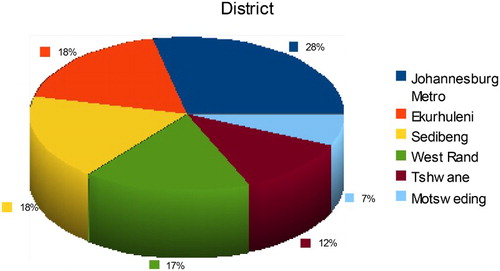

The social sector of the EPWP in Gauteng was implemented in all six districts of the province. The majority of the respondents (28.5%) were working in Johannesburg Metro. The remaining respondents were more or less equally distributed throughout the five other districts, except in the Motsweding district which had the least number of respondents, namely 7% ().

The majority of respondents in the quantitative study were black Africans. All of the respondents in the qualitative study were also black Africans.

The profile of the participants and the areas where they live appears to suggest that the programme is being implemented only in historically black communities. This racial distribution is in line with the findings of Hunter & Ross (Citation2013:749), according to whom the majority of stipend-paid volunteers come from mainly black and mixed-descent ethnic groups. This is applicable to the social sector of the EPWP because most of the beneficiaries who render the home-based care services are volunteers who receive a stipend and not a salary. This was confirmed by one of the participants in the focus groups: ‘ … it’s a stipend, it does not cover all expenses, only a bit, like if you look at the bigger picture, only 5%’.

5.2. The social sector of the EPWP as a strategy to reduce poverty

To gauge responses regarding the social sector of the EPWP as a poverty reduction strategy, the respondents were asked to give their level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale with nine items. The five-point scale was collapsed to three points during the analysis of the data. The responses are displayed in .

Table 2. Social sector of the EPWP as a strategy to reduce poverty.

The responses, as reflected in the table, indicate that the majority of the respondents agreed on all of the items. The following items had the highest levels of agreement: the social sector of the EPWP enabled participants to access education (87.4%); the social sector of the EPWP enabled participants to access healthcare (72%); and the social sector of the EPWP contributed to the reduction of illiteracy (72%). The findings of the study have revealed that the social sector of the EPWP has made a contribution to poverty alleviation by enabling participants to access education (which reduces illiteracy) and healthcare. In this regard, McCord (Citation2003) states that the empowerment of participants in Public Works Programmes through training is one of the important objectives of these programmes. This is because the HCBC and ECD programmes both include training of participants, and hence the emphasis on access to education and the reduction of unemployment. The participants also receive a stipend.

The items with the lowest levels of agreement were: the social sector of the EPWP slows down the rural–urban migration by creating jobs (55.3%); and the social sector of the EPWP is contributing to the reduction of vulnerability by enabling participants to have more assets (55.3%). These findings suggest that there are not enough opportunities in rural areas to prevent people from moving to urban areas. The reduction of the rural–urban migration is one of the goals of the Public Works Programmes set by the United Nations (Citation2009). The responses also indicate that the income earned by participating in this programme is not enough to put participants in a position where they can acquire assets such as property and land. The acquisition of assets is important because it helps to reduce vulnerability.

In the focus group discussions, the participants revealed that they view poverty reduction from two perspectives, namely:

poverty reduction at a community level, and

poverty reduction at their own individual level.

The participants believed that as beneficiaries of the EPWP they were involved in poverty reduction at a community level with regards to dealing with poor children in informal settlements in their communities. They help to reduce poverty in communities through short-term interventions such as handing out food parcels while at the same time looking at other long-term strategies.

As a long-term strategy to promote food security, participants assisted communities to establish food gardens. This is an attempt to reduce poverty by ensuring that families have food. This is also more sustainable than handing out food parcels. In this regard, one participant in the women’s focus group stated: ‘We also encourage them to start a food garden, because there is no one working in the household. So, with a vegetable garden they can just pick food and cook it and eat.’

Some participants in the youth focus groups also highlighted the fact that they helped to reduce poverty in communities by promoting education so that community members could gain skills, and they also provided children with school uniforms. As one participant said: ‘If you go to the village that side at the squatter camp, the children from there can come here and get some food parcels … mmm, then they can also get some school uniform. Somehow this reduces poverty.’

The contribution to poverty reduction through education is also emphasised by The Presidency (Citation2008) when it mentions that one of the strategies to reduce poverty in South Africa is to enhance access to education.

5.3. Poverty reduction on an individual level

The participants also revealed that although the stipend they receive is not much, it has enabled them to do different things to reduce poverty.

Participants became creative and found ways to increase their income by buying goods in bulk. For example, they will buy socks and other items of clothing and sell them for a profit. One participant in the youth focus groups said: ‘Like for example selling socks. We buy them at Marabastad in bulk because they’re cheaper that way … and then we come here to sell them, just to have another form of income.’

Participants also formed social clubs where they each contributed a set amount of money monthly and the money benefits all of the participants. One participant in the women’s focus group stated: ‘We also form groups where we each take out R200 … and the pot goes to this one, one month and another, the next … We at least can earn more than R1000 some months.’

Participants also assert that communal food gardens are also a means of generating income, as they jointly produce vegetables and sell them to shops to make money. This is explained by a participant from a rural area:

We find that there are women and men but they are doing nothing, they do not contribute anything so we encourage them to start a garden. Yes, and to sell some of their produce. When the products are ready, we sell it and get some money at least and then there is a project like Oom Piet’s in Pretoria North which sells vegetables.

The discussion shows that there are similarities between the women and the youth, and the rural communities. All groups have a similar approach to alleviating poverty, as they pool their resources together in different ways, instead of struggling individually.

This approach to poverty alleviation confirms that the social sector of the EPWP follows the social development approach, because one of the principles of social development is that social development is carried out through various strategies, which are linked to economic development. Here the strategy is to form clubs, communal food gardens and entrepreneurial groups to achieve economic development.

Participation in the EPWP also had a snowball effect because it led to other opportunities to reduce poverty. For example, as volunteers, during elections they were approached by Independent Electoral Commission officers to assist and received an opportunity to earn extra money.

6. Discussion

The South African government’s strategies to alleviate poverty are numerous, and they include the following: creation of economic opportunities, investment in human capital, basic income security, housing and household services, comprehensive healthcare, access to assets and social cohesion.

The social sector of the EPWP is encompassed under two of these strategies – namely, the creation of economic opportunities and investment in human capital – because the programme includes various types of training for participants.

The quantitative study confirmed this, as respondents indicated that the social sector of the EPWP has made a contribution to poverty alleviation amongst the participants. There was no agreement level below 50% on this item of the questionnaire.

The aforementioned was also confirmed by the focus group discussions. Here participants made a distinction between their own poverty alleviation, as beneficiaries of the social sector of the EPWP, and the contribution they were making towards poverty alleviation in the communities in which they are working. This was confirmed by one participant who stated: ‘if you go to the village that side of the squatter camp, the children from there come here and get some food parcels, and they can also get some school uniforms. Somehow this reduces poverty’. This confirms the quantitative findings.

7. Summary and conclusion

This study shows that the social sector of the EPWP has made a contribution to poverty alleviation by enabling participants to access education and providing them with a stipend. In turn, participants assist communities to access food by establishing food gardens to alleviate poverty. These are more sustainable types of projects.

Some participants have initiated small enterprises through the establishment of communal food gardens and the selling of their produce to local businesses. They also buy goods in bulk and sell them at a small profit. This communal approach was found amongst women, youth and rural communities.

The study has also revealed that women and youth have benefitted from the social sector of the EPWP’s efforts at poverty alleviation. Persons with disabilities, although they are an official target of the programme, did not benefit because they were not recruited to participate in the social sector of the EPWP in Gauteng.

Although one of the goals set for Public Works Programmes by the United Nations is to help to reduce rural–urban migration, there is no strong evidence that the programme has made an impact in this regard.

Based on the issues discussed in this article, the following recommendations are made with regards to the social sector of the EPWP in Gauteng:

Strategies should be put in place to make the social sector of the EPWP sustainable. This can be done by identifying partners in the private sector to support the programme and by involving beneficiaries of the programme more actively in project planning and implementation.

The social sector of the EPWP should be implemented in all areas of the Gauteng province to include all population groups because this will enhance its sustainability.

Officials and beneficiaries should be trained to enable them to undertake sustainable development projects.

Information regarding poverty alleviation programmes, including the social sector of the EPWP, should be disseminated widely to all communities to ensure maximum participation and sustainability.

The involvement of participants as volunteers in the programme should be reconsidered, because this renders the programme unsustainable.

Persons with disabilities should be actively recruited to participate in the social sector of the EPWP. Alternative work opportunities should also be explored to create an enabling environment or persons with disabilities to participate in the social sector of the EPWP, thus avoiding their exclusion.

The departments implementing the social sector of the EPWP in Gauteng should put more effort into recruiting persons with disabilities so that they can benefit from poverty alleviation projects.

References

- African National Congress, 1994. Reconstruction and development programme. Umanyano Publications, Johannesburg.

- Chen, RS & Syder, E, 2006. Where the poor are: An atlas of poverty. Center for International Earth Science Information Network, New York.

- De Vos, AS, 2005. Qualitative data analysis. In De Vos, AS, Strydom, H, Fouche, CB & Delport, CSL (Eds.), Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human service professions. Van Schaik: Pretoria, pp. 333–349.

- Delport, CSL & Fouche, CB, 2011. Mixed methods research. In De Vos, AS, Strydom, H, Fouche, CB & Delport, CSL (Eds.), Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human service professions. Van Schaik, Pretoria. pp. 433–448.

- Department of Education, 2001. Education white paper 5 on early childhood education. Department of Education, Pretoria.

- Department of Health, 2008. National guidelines on home based care/community based care. www.health.gov.za. Accessed 27 September 2008.

- Department of Social Development, Department of Education and Department of Health, 2004. Expanded public works programme social sector plan 2004/5–2008/9. Government Printers, Pretoria.

- Dev, SM, 2009. Public Works Programmes in India. www.worldbank.org. Accessed 26 June 2009.

- Ferreira, FHG & Ravallion, M, 2008. Global poverty and inequality: A review of the evidence. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Hunter, K & Ross, E, 2013. Stipend-paid volunteers in South Africa: A euphemism for low-paid work? Development Southern Africa 30(6), 743–59. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.860014

- International Federation of Social Work, 2014. Global agenda for social work and social development: First report – Promoting social and economic equalities. International Social Work 2014, 57(S4), 3–16.

- International Labour Organisation, 2009. Facts on poverty in Africa. www.ilo.org. Accessed 15 September 2009.

- Lombard, A, 2007. The impact of of social welfare policies on social development: An NGO perspective. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk 43(1), 295–315.

- McCord, A, 2003. An overview of the performance and potential of public works programmes in South Africa. CSSR Working paper no 49UCT Centre for Social Science Research, Cape Town.

- Midgley, J, 1995. Social development: The developmental perspective in social welfare. Sage Publications, London.

- Musekene, EN, 2013. The impact of a labour-intensive road construction programme in the Vhembe District, Limpopo Province. Development Southern Africa 30(3), 332–346. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.817301

- National Planning Commission, 2011. National development plan. National Planning Commission, Pretoria.

- Netshitenzhe, J, 2012. South Africa reflects extreme forms of inequality. The Sunday Independent, 19 August, p. 13.

- Patel, L, 2005. Social welfare and social development. Oxford University Press, Cape Town.

- Republic of South Africa, 2010. Office of the president. Millenium development goals: Country report. Government Printers, Pretoria.

- Schenck, CJ & Louw, H, 2010. Poverty. In Nicholas, L, Rautenbach, J & Maistry, M (Eds.), Introduction to social work. Juta, Cape Town, pp. 351–372.

- Schneider, RL & Netting, FE, 1999. Influencing social policy in a time of devolution: upholding social work’s great tradition. Social Work 44(4), 349–57. doi:10.1093/sw/44.4.349

- Southern African Regional Poverty Network, 2005. Addressing the needs of vulnerable groups. www.sarpn.org.za Acessed 24 February 2006.

- Statistics South Africa, 2010. Monthly earnings of South Africans. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Statistics South Africa, 2011. Social profile of vulnerable groups in South Africa 2002–2010. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Strydom, C & Tlhojane, ME, 2008. Poverty in a rural area: The role of a social worker. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk 44(1), 34–49.

- Subbarao, K, Bonnerjee, A, Carvalho, S, Ezemenari, K, Graham, C & Thompson, A, 1997. Safety net programs and poverty reduction: lessons from cross-country experience. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Swanepoel, H & De Beer, F, 2006. Community development: Breaking the cycle of poverty. Juta, Landsdowne.

- The Presidency, 2008. Towards an anti-poverty strategy for South Africa: A discussion document (draft). The Presidency, Pretoria.

- Triegaardt, JD, 2006. Reflections on poverty and Inequality in South Africa: Policy considerations in an emerging democracy. Paper presented at the annual Association of South African Social Work Education Institutions (ASASWEI), 18–20 September, University of Venda, South Africa.

- Twikirize, JM, Asingwire, N, Omona, J, Lubanga, R & Kafuko, A, 2013. The role of social work in poverty reduction and the realisation of millennium development goals in Uganda. Fountain Publishers, Kampala.

- United Nations, 2009. Self-employment programmes and public works programmes. www.un.org Accessed 9 July 2009.

- United Nations Development Programme, 2010. Millenium development goals: Country report 2010. United Nations Development Programme, Pretoria, South Africa.

- World Bank, 1997. Public works programmes: what are the income gains for the poor www.worldbank.org Accessed 15 June 2009.

- Woolard, I, 2002. An overview of poverty and inequality in South Africa. Working paper prepared for DFID (SA) July 2002.

- Yeasmin, S & Rahman, KF, 2012. Triangulation research method as the tool of social science research. BUP Journal 1(1), 154–63.

- Zegeye, A & Maxted, J, 2002. Our dream deferred: The poor in South Africa. South African History Online and Unisa Press, Pretoria.