ABSTRACT

There is growing recognition of the critical role that National Monitoring and Evaluation Systems can play in achieving sustainable development through enhancing effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability of policies and programmes. The South African government legislated the Government-wide Monitoring and Evaluation System (GWMES) in 2009. The extent of gender responsiveness of the system has not been assessed yet gender mainstreaming ensures that gender needs, realities and issues are consistently and specifically considered in policies, programmes and projects. The study utilises data from document reviews and key informant interviews to assess gender mainstreaming in the National Evaluation Policy (NEP) and the GWMES using a gender diagnostic matrix. Results indicate that the GWMES and NEP rank low in most gender-mainstreaming dimensions. However, the study concludes that existing policies and institutional frameworks if well supported by multiple stakeholders are conducive for effective gender mainstreaming within the GWMES in South Africa.

1. Introduction: the need for gender mainstreaming in NMESs

There is growing recognition of the critical role that NMESs can play in achieving sustainable development through enhancing effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability of policies and programmes. National Monitoring and Evaluation Systems (NMES) inform evidence-based policy-making and improve transparency through strengthening accountability and relationships between policy-makers and civil society. They build a performance culture within public institutions at all levels, inform budget decision-making and provide information and knowledge for effective policy implementation. In the last two decades, a number of countries legislated and institutionalised NMESs owing to demands for improving accountability and the need to meet national and global development agendas (Mckay, Citation2008; Talbot, Citation2010). According to a global mapping of National Evaluation Policies (NEPs) conducted by the Parliamentarians Forum for Development Evaluation for South Asia with support from EvalPartners, in 2013, fewer than 20 countries in the world had formal NEPS, including three African countries (Rosenstein, Citation2013). The regional consultation in Africa in 2017 revealed that, among 54 African countries only Ethiopia, Kenya, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe had endorsed national evaluation policies. Among these, only Zimbabwe and Ethiopia included direct reference to gender equality in their NEPs (AfrEA, Citation2017).

The need for engendering NMESs has come to the fore, with emphasis on gender equality (UN Women, Citation2015). Engendering monitoring and evaluation systems entails viewing policies, programmes and projects being evaluated through a gender dimension to ensure that gender needs, realities and issues are consistently and specifically considered at each stage of the Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) process (Brisolara, Citation2014). Such a process involves gender mainstreaming at the policy and institutional levels of the NMES as well as M&E in practice (strategies, methodologies and tools). It has become increasingly clear that a gender-sensitive NMES has the capacity to assess gender specific impacts of policy and programme interventions that can have multiplier effects on socio-economic development. Gender mainstreaming has been proven to have positive impacts on economic productivity through enabling women to reach their full potential and improving family welfare (OECD, Citation2000). In addition, engendering NMESs can change gender-related power relationships using broad stakeholder inclusive and participatory mechanisms (UN Women, Citation2015). Research has shown that the female proportion of the world's human capital is undervalued, and countries are underinvesting in utilising women's potential (OECD, Citation2008). Such a market and systems failure can be explained in terms of gender constraints, which are based on the socially constructed and historically developed roles of men and women. Engendering of NMESs, policies, programmes and projects is critical in minimising the socio-economic costs of gender inequality.

The declaration of 2015 as the International Evaluation Year has helped boost evaluation capacities in many countries, but doing so in a gender-sensitive way remains an issue, especially the implementation of gender-responsive evaluations. A study by De Orte et al. (Citation2015) on challenges in integrating gender equality in NMESs for Madagascar, Mexico, Spain, Egypt, Morroco, Uganda, Tunisia and Kenya identified a number of key challenges. These included: limited funds for evaluation; limited capacity for continuous collection of gender disaggregated data and implementation of gender-sensitive indicators; and poor networking between advocates, practitioners and policy-makers. In addition, although there is a rich theoretical body from feminist research that can inform gender-mainstreaming practice, there is resistance for mainstreaming gender equality by practitioners owing to ideological and political views. These issues tend to highlight the need for collaborative efforts by policy-makers, civil society and evaluation practitioners to enhance gender mainstreaming.

In recent years, concerted efforts have been made by various institutions to drive the gender mainstreaming agenda in evaluations. The Food and Agricultural Organization and other United Nations agencies have improved the availability of gender-disaggregated data. There has been an increase in the quantity of training materials, toolkits and guidelines for gender-sensitive M&E. Examples include inter alia: the Danida gender-sensitive monitoring indicators’ technical advisory services (DANIDA, Citation2006), World Bank toolkit on gender issues in M&E in agriculture (World Bank, Citation2012), GIZ's guidelines on designing a gender-sensitive results-based monitoring system (GIZ, Citation2014), The Centre for Learning on Evaluation and Results for Anglophone Africa (CLEAR-AA) diagnostic studies on gender responsiveness in NMESs and the UN Women guidelines for managing gender-sensitive evaluations (UN Women, Citation2015).

This study aims at contributing to the gender-mainstreaming discourse for NMESs. A review of literature indicates a dearth on research in this discourse, particularly within the African context, and in particular, the GWMES has not been assessed for gender mainstreaming. This study therefore assesses gender responsiveness within the institutional arrangements of the GWMES. The research question addressed is: to what extent are the NEP and GWMES in South Africa responsive to gender mainstreaming? The focus of the study was not on gender mainstreaming in general, or how gender interventions, programmes or projects are monitored and evaluated, but on how the GWMES includes aspects of gender equality. It is envisaged that the findings will provide knowledge on the process of gender mainstreaming to other countries currently developing NMESs. The proceeding section provides a synopsis of gender policies and GWMES for South Africa to create a context for the study.

2. Building a context: overview of NMESs and gender policies for South Africa

2.1 Brief overview of the South African gender policy

The first democratic government of South Africa in 1994 inherited a deeply divided society with gender inequalities. Even within racial groups, communities were typically male-dominated. Discrimination based on gender led to women becoming more vulnerable to stressors such as unemployment, poor health and low educational status (Van Der Byl, Citation2014). Post-apartheid South Africa provides pro-gender equality constitutional and legal frameworks. The National Development Plan (NDP 2030) identifies rural women and informal settlers as the most vulnerable with regard to gender inequality, poverty and unemployment.

South Africa has ratified a number of international instruments promoting gender equality and the protection of women's rights, including: Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Southern African Development Community Protocol on Gender and Development, Millennium Development Goals, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Beijing Platform for Action (BPFA) and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People's Rights on the Rights of Women. A number of key national policy documents initiated a trajectory on gender equality: the Framework for Transforming Gender Relations, Constitution of South Africa (1996), Commission for Gender Equality Act (1996), Women Empowerment and Gender Equality Bill (2013), National Gender Policy Framework, Gender Equality Strategic Framework and Gender Policy Framework for Local Government.

A National Gender Machinery (NGM), which comprises government and civil society, was formed in 1997. The mandate for gender mainstreaming lies with the Department of Women (DoW). In 1997 the Office on the Status of Women was established in the Presidency to steer the national gender programme. It championed the development of the National Policy Framework for Women Empowerment and Gender Equality that was approved by Cabinet in 2000. In 2009 the President pronounced the establishment a Ministry of Women, Children and People with Disabilities (DWCPD), and in 2014 the department evolved into a dedicated ministry for women (DoW).

2.2 Brief overview of the South African NMES

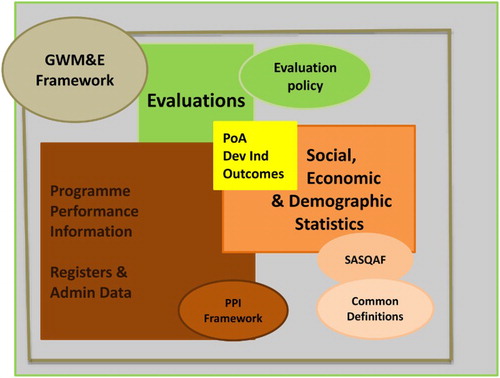

The South African NMES is coined the Government-wide Monitoring and Evaluation System (GWMES). South Africa initially had a top-down M&E system that focused on accountability and improved management. The system has evolved to focus on improving performance, accountability, knowledge generation and improving decision-making (Goldman et al., Citation2014). The GWMES consists of three data terrains: programme performance information; social, economic and demographic statistics; and evaluation. The set of policies consists of the Government-wide Monitoring and Evaluation Policy Framework (GWMEPF) by the Presidency, the Framework for Managing Programme Performance Information (FMPPI) by the National Treasury, the South African Statistics Quality Framework (SASQFP) by Statistics South Africa and the National Evaluation Policy Framework (NEPF) by the Department of Planning Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME) (see ).

Figure 1. Components of the GWMES. Source: Engela & Ajam (Citation2010).

The aim of the GWMES is to provide an integrated and encompassing framework of M&E principles, practices and standards to be used throughout Government. It functions as an apex-level information system, which delivers useful M&E products for its users (The Presidency, Citation2007). The GWMES consists of different systems. The main systems include outcomes monitoring, the Management Performance Assessment System (MPAT), the Local Government Monitoring Model and the National Evaluation System. There are various other sector specific systems, including the Health and Education Information Systems (Phillips et al., Citation2014). The latter and the local government systems were not included in this assessment

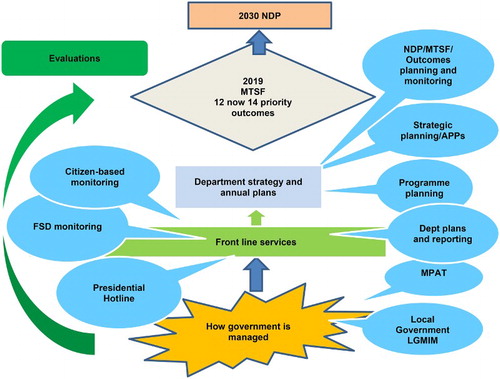

The Presidency plays a crucial role in the coordination, monitoring, evaluation and communication of government policies and programmes. In 2014 the DPME was established through the merging of the National Planning Commission Secretariat in The Presidency with the Department of Performance Monitoring and Evaluation (that was established in 2010). The merging of the planning, M&E function into the new DPME has resulted in the reorganisation of the department into to the following five programmes: Administration; Outcomes Monitoring; Institutional Performance Monitoring and Evaluation; National Planning; and National Youth Development Programme.

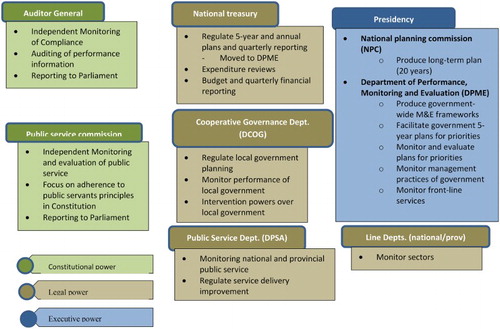

The DPME is the custodian of GWMES (see ). Other key M&E role players include The National Treasury and Statistics South Africa. Other M&E stakeholders include the Department of Public Service Administration, the Provincial Offices of the Premier, the Public Service Commission, the Auditor General (AGSA), South African Monitoring and Evaluation Association (SAMEA), universities and research institutions. Universities, research institutions and M&E capacity building institutions such as the Centre for Learning on Evaluation and Results for Anglophone Africa (CLEAR-AA) play an important role in skills development. After 2009, a number of organisations became responsible for planning, M&E. The responsibility of the National Treasury regarding the Strategic Plans and Annual Performance Plans was transferred to the DPME. shows the main stakeholders in the South African M&E system.

Figure 2. Role of DPME. Source: Goldman (Citation2016).

Figure 3. Main stakeholders in M&E in South Africa. Source: (Phillips et al., Citation2014:394).

Gender mainstreaming within the GWMES is expected to be given due attention in light of the SDGs’ focus to ‘leave no-one behind’, and the EvalAgenda 2020s aim to use a gender lens in all evaluations (EvalPartners, Citation2016). Both the departments mandated with M&E and gender mainstreaming have very important mandates that have implications across all government structures. Gender mainstreaming, through the establishment of gender focal points (GFP) has been documented in the Gender Policy Framework since 2003 as a strategy to deepen the transformation of the public service. However, currently gender mainstreaming as a strategy is not effective mostly, as those who are expected to influence the mainstreaming process are not strategically positioned to influence change at all levels of government, including departments and GFPs (Van Der Byl, Citation2014) ().

Table 1. Overview of main aspects for NMES in South Africa.

3. Concept of gender mainstreaming

The process of institutionalising gender into NMESs addressed in this paper derives rationale from the concept of gender mainstreaming, which surfaced in the late 1980s to the early 1990s (Andersen, Citation1993; True, Citation2003; Sueng-kyung & Kyounghee, Citation2011). The BPFA of 1995, a key United Nations statement on gender equality across all sectors, gave rise to gender mainstreaming as a tool for policy-makers (Verloo, Citation2006; Unterhalter Citation2007:130). Since then, gender mainstreaming has been the key approach to addressing the perceived cause of gender inequality, i.e. the genderedness of policies, systems, procedures and organisations. In recent years, collaborations among feminist researchers, advocates and policy-makers have integrated gender analysis as a routine practice for public policy-making by many governments (True, Citation2003).

Mainstreaming a gender perspective is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in all areas and at all levels (Kwigisa and Ssendiwala, Citation2006). It is based on the foundations of human rights, deepening democracy and recognition of sociocultural differences between men and women. Within the context of NMESs, gender mainstreaming aims at a fundamental transformation, by eliminating gender biases and redirecting policies, programmes and projects so that they can contribute towards the goal of gender equality. It is thus, an integral dimension of the design, implementation, M&E of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres to enhance equality between men and women (Corner, Citation1999; Rai, Citation2003). It entails the consistent use of gender perspectives at all stages of developing M&E systems. Gender mainstreaming involves multiple levels in governance as well as multiple shifts in governance of institutions within NMESs. It involves not only national or regional state bureaucracies, but also supranational and international players. Multiple shifts in governance are required, since the strategy focuses on reorganisation of policy processes and strategies with a shift in responsibilities (Verloo, Citation2006:13). There is need for comprehensive gender mainstreaming strategies that systemically permeates all aspects of institutions and services and orients values, policies and organisational processes within the NMES to take account of gender equality.

Gender mainstreaming developed as an alternative to earlier approaches for addressing gender inequalities, which include Women in Development (WID) and Gender and Development (GAD). The WID paradigm of the 1970s promoted gender equality in the economic development agenda of state institutions and international agencies through promoting women focused projects (Tinker, Citation1990). It evolved into GAD in the late 1980s, and some critics associate the shift to a need for institutional transformation. It is argued that WID incorporated women into existing institutional frameworks without transforming the socio-institutional frameworks that shaped gender inequalities. They view it as having failed to challenge power differentials in gender relations within the wider political economy and to leverage women's interests in organisations (Karlsson, Citation2010:499). The progression towards gender mainstreaming has received its fair share of critique. For example, some critics view the shift of the gender discourse from the realm of feminist theory towards integration into local policy formulation arena as a compromise from the focus on ‘women's issues’. Within this context, gender mainstreaming has been viewed as part of a broader instrumental capitalist agenda creating gender experts at the expense of empowering the grassroots (True, Citation2003:369). However, some feminist scholars view gender mainstreaming as an appropriate extension of preceding paradigms which is critical for sustainable development (OECD, Citation2008; UN Women, Citation2015).

The theoretical constructs of gender mainstreaming are not well documented and seem to have been overlooked in literature and practice (Kwigisa & Ssendiwala, Citation2006:594). For example, it is argued by Beveridge et al. (Citation2000:388) that:

[t]here has been little attempt to develop a general theory of mainstreaming which transcends the diversity of state practice in order to provide a universal frame of reference, or set of criteria, by which mainstreaming may be understood and particular mainstreaming initiatives judged.

This has led to various interpretations of mainstreaming without a commonly agreed framework. Despite the varying interpretations emanating from socio-political, cultural and economic contexts, scholars have identified a few overarching tenets for gender mainstreaming. True (Citation2003), Rai (Citation2003) and Jahan (Citation1996) give a few elements that guide gender mainstreaming assessments in this study. These include, inter alia, the assertions that; gender mainstreaming strategies are premised on the assertion that inequalities exist between women and men that shape policies and outcomes and that such disparities can be addressed through policy and programme reforms informed by gender diagnosis. Second, in contrast to anti-discrimination, mainstreaming does not necessarily require the placement of women in decision-making roles but utilises policy instruments that institutionalise mechanisms for addressing gender inequality. Third, the gender mainstreaming agenda should be driven by institutional outcomes that are people-centred rather than inputs and promises. It must allow policy dialogue at various levels recognising the competing dialogues that operate in global and national society and occasionally within institutions themselves around a transformative gender equality agenda. Gender mainstreaming should drive changes on many fronts in decision-making structures and processes, in articulation of objectives, in prioritisation of strategies, in the positioning of gender amidst competing emerging concerns and in building a critical mass of support among both men and women. Finally, clear political will and allocation of adequate resources for mainstreaming, including additional financial and human resources if necessary, are important for translation of the concept into practice.

With regard to implementation of gender mainstreaming, various frameworks have been proposed. Leo-Rhynie and Institute of Development and Labour Law (1999) in Karlsson (Citation2010) propose three pillars: a gender-management system; policy regulatory framework; and plans, programmes and projects. The gender-management system comprises organisational units, teams and personnel (gender machinery) to lead and coordinate the transformative process. The policy and regulatory framework must have indicators for measuring provision, access, participation, resources, outcomes and impacts. The plans, programmes and projects allow implementation of the gender-mainstreaming process.

In a bid to offer clarity, Verloo (Citation2006:23–4) contrasts gender mainstreaming with two other commonly utilised policy-making tools for addressing gender inequality; equal treatment and specific equality policies. Equal treatment focuses on enhancing equal access and addresses existing inequalities in legislation to allow equality among citizens. It is crafted within a liberal discourse that allows citizens to utilise their equal rights. Specific or targeted gender equality policies recognise that individuals have varying capacities in utilising equal rights owing to gender inequalities. They focus on creating conditions that enhance equality in policy outcomes to counterbalance unequal societal circumstances for men and women. They are usually conducted by specialised state institutions and by gender equality agencies. The distinctive features of the approaches are outlined in .

Table 2. Different approaches in gender-equality policies.

There are a limited number of evaluative and reflective studies on the implementation of gender mainstreaming in the African context. However, review of literature from European experiences highlights a number of key lessons. A study by Behning and Serrano Pascual (Citation2001) argues that the understanding and adaptation of the gender mainstreaming concept varies widely (multiple interpretations of policy-making). Again, this calls for a need for theoretical development of the concept to guide practice. The study argues that most strategies focus on women as the subject of change, fitting women into the status quo rather than transforming the status quo. Braithwaite (Citation1999) argues that most strategies have no clear objectives, are not based on consensus and have no consistent goals as there is a continuous shift in gender equality concepts leading to ineffectiveness of gender mainstreaming endeavours. A review of gender mainstreaming by international institutions conducted by Moser and Moser (Citation2010) identified a number of key constraints in the implementation of gender mainstreaming. These include inter alia: inconsistency and fragmentation of activities; failure to move beyond planning to implementation (policy evaporation); organisational culture; resistance; poor mechanisms for accountability; and poor M&E mechanisms. The study asserts that most efforts are inconsistent and involve a few fragmented activities. Policy commitments to gender mainstreaming seldom go beyond the planning phase towards implementation. This can be due to factors such as lack of staff capacity, organisational culture and attitudes, resistance to the notion of gender equality, treating gender equality as a separate process and lack of ownership of the policy. This study aims at contributing to the growing discourse of gender mainstreaming.

4. Methodology

This study assessed the gender responsiveness of the NEP and GWMES for South Africa. The study is qualitative and utilised the following tools: document reviews, observations and key informant interviews. Documents reviewed were; policy documents; national constitution, M&E strategies and plans; publications by institutions within the NMESs; guidelines and M&E standards; and progress reports. Key informant interviews were conducted in 2016 with representatives of key stakeholders who were identified using a snowball sampling process. gives details on the data collection tools and sample sizes.

Table 3. Sample sizes of data sources.

A gender diagnostic matrix was used to assess the different dimensions in line with the defined criteria. Each criterion consisted of various questions to guide the assessment and scoring. outlines the Gender Diagnostic Matrix (GDM). The dimensions and criteria reflect the conceptualisation of gender mainstreaming for this study. These were developed through a consultative and iterative process including evaluation and gender experts.

Table 4. Gender diagnostic matrix.

The rating scale illustrated in was used to assess and score each of the questions in the GDM. This was used for all data collection tools including document reviews, observations and key informant interviews. Trustworthiness and rigour of the tool and the rating process were ensured through triangulation of information sources, i.e. interviewing representatives from different stakeholder groups and the incorporation of document reviews and personal interviews. Two researchers rated the different variables from the different data sources and reached consensus regarding the rating. An additional two gender experts from the Africa Gender and Development Evaluators Network (AGDEN) reviewed the scores and compared it with the application of the GDM in two other studies performed simultaneously in Benin and Uganda.

Table 5. Rating scores.

5. Results and discussion

5.1 Government-wide M&E policy framework

5.1.1 Gender equality

The gender equality assessment score was rated at 46%. As described in section 2.1 there are various legislations that guarantee gender equality and women's empowerment in South Africa, which are supposed to inform the four key policies that guide the GWMES. Results indicate that none of these policies mention gender or gender equality. Gender is only mentioned once in the GWMEPF as a critical skill needed for evaluations. The GWMEPF has as a key principle (number 2) that the M&E should be rights based. The only other mention of human rights is in the foreword of the NEPF. The GWMEPF states in principle 2 and 3 that M&E should be pro-poor, but none of the other policies directly mentions poverty reduction. In addition, none of the international conventions on women's rights including that South Africa has signed are being reported indicated in the GWMEPF. The four key policies of the GWMES are all legislated, in full implementation and are all based on a results-based framework. Public policy performance monitoring is conducted through the Management Performance Assessment Tool (MPAT) and stipulated in the GWMEPF and FMPPI. Nevertheless, the policies (including the FMPPI) do not include gender-responsive indicators. There are only limited indicators on specific gender mainstreaming aspects including employment equity and human resources.

5.1.2 Public policy evaluation decision-making

Decision-making was rated low (33.3%). Although results show that the GWMEPF and three other associated policies fully addressed When? What? How? to monitor and evaluate public policies and implementation, no mention is made of gender-responsive evaluations. In the NEPF there is an implication that appropriate approaches and methods are to be used. The FMPPI addresses equity, but in a more broad sense and regarding specific to benefit-incidence studies. There are descriptions for the use of information (M&E results), but not specific to address inequalities or improve gender equality. For example, the FMPPI (Step 6) stipulates how information on performance contributes to decision-making and could facilitate corrective action, but blind on gender equality. Regarding the disaggregation of data by sex, the South African Statistical Quality Assessment Framework (SASQAF) (the main policy guiding data and statistics) does not stipulate gender disaggregated date, but it is implied throughout the Statistics SA's definition of fitness for use and the eight dimensions of quality.

5.1.3 Participation

Participation was rated at 50%, and respondents felt that it needed to be reflected in the policies in explicit mechanisms to allow both men and women to express opinions and exert influence. Results from Key Informant Interviews (KII) indicated that the DPME partnered closely with other government departments (Statistics SA and the Treasury in particular) and SAMEA regarding M&E policies and plans. Participation of other evaluation experts is stipulated in the NEP but what is not explicit is the inclusion and participation of gender experts or departments. The fact that the mandate for gender mainstreaming falls with the DoW (and specific aspects such as social empowerment of women with the Department of Social Development and other departments) gender is seen as the work of these departments. Respondents from KII felt that cooperation modalities were not yet in place to ensure participation of gender experts in all departments and especially in the development of policies for GWMES.

5.1.4 Evaluability, review and revision

Evaluation was rated at 50%, and at the time of the study, the GWMEPF, SASQAF, FMPPI and NEPF had not been revised. This, according to KII, was explained in terms of the rollout of the NEP where there was no single National Evaluation Policy in South Africa, but rather an evolving system that started in 2009 with the development of the GWMEPF. Subsequently the SASQAF, FMPPI and lastly the NEPF were developed through incorporating lessons learnt in recognition of changing political contexts. However, evidence from previous plans that have been revised and evaluated indicate non adherence to take gender mainstreaming (local or international) best practice or developments into consideration. The latest NEP (2016/17–2018/19) does not put emphasis on gender responsiveness of the evaluations, assessments or use.

5.1.5 Sustainability

The GWMES has policies in place for all three data strands in the form of the SASQAF, FMPPI and NEPF. The development of the GWMES and the policies were reported to be up to date and well developed. The M&E policies are supported through updated plans. Document reviews indicated that Cabinet was briefed by DPME on the latest, 5th National Evaluation Plan for 2016/17 to 2018/19 on 26 April 2016. Although mandates of the GWMES and for gender mainstreaming are clear, respondents felt that more direct focus was needed for the integration of the two systems with regard to gender equality as measures to integrate gender mainstreaming into the GWME Policies were not clear. Although the sustainability of the policies (through plans) was perceived as high, the sustainability of the system to ensure that gender responses would be captured, adjusted and maintained was not evident and needs to be developed.

5.2 GWMES

5.2.1 Gender equality

Results indicate that the GWMES in South Africa includes some aspects of gender equality, but lacks provisions for gender-disaggregated data. Results from KII indicate that there is no specific structure for gender-responsive evaluations. Furthermore, the results indicate overlapping roles and lack of clarity on specific mandates regarding gender mainstreaming and M&E. It was highlighted that, although the DPME involve a number of stakeholders in M&E activities (including citizen-based monitoring [CBM], SAMEA, experts and government departments), such engagements do not integrate gender mainstreaming. KII also highlighted that, although the DPME has staff with specialised gender experience, they do not have a general culture of gender mainstreaming in their routine operations. There is no specific structure for gender-responsive evaluations. The NGM has been criticised for being fragmented and lacking coordination and cohesion. According to the DoW (Citation2015) the GFPs were at varying levels of appointment and placement, away from the points of leverage and decision-making and were not positioned to influence policy-making and decision-making. The resulted in gender neutral decisions regarding to policy, budgets and programmes.

Results also indicated that gender audits and monitoring of legislative compliance were seen as the responsibility of the Commission for Gender Equality (CGE), a specialised structure with gender specialists. It was highlighted that the DPME has developed numerous guidelines and policies, including procurement and process documents that were viewed as not being gender-responsive (and do not stipulate gender aspects or standards). Document reviews indicate that although the DPME has developed numerous guidelines and policies, including procurement and process documents, these guidelines are not gender-responsive (and do not stipulate gender aspects or standards). However, the quality of these guidelines clearly indicates that the DPME has the competency and will to develop guidelines with precise content. This offers an important opportunity in that guidelines can be developed around aspects such as gender-responsive evaluations, mainstreaming of gender into all evaluations, capturing and using gender-disaggregated data and the use of engendered evaluations for policy change.

5.2.2 Decision-making

Decision-making received a score of 25%. Results indicated that, in South Africa, the NGM, Voluntary Organisation for Professional Evaluators and gender advocates did not play a key role in determining gender responsiveness. The DPME is fully empowered to determine national evaluation schedules (within budget and priority limits). KIIs indicated that at the time of the study, the gender was not functioning appropriately to advocate for gender responsiveness of the national evaluation or monitoring efforts, or exert influence on methodologies, influence the budget of national evaluations and improve gender responsiveness. The CGE, as a statutory Chapter 9 institution, has the mandate to monitor compliance of all institutions (including public, private and other organisations) with constitutional gender equality. However, the budget constraints and lack of punitive and other corrective authority seem to leave this important role player ‘without teeth’.

5.2.3 Participation

Participation was rated high (75%), with high levels of involvement by ministries and agencies in GWME. The GWMEPF stipulates that all government departments and agencies are part of M&E. Provincial Premiers’ offices have M&E departments that coordinate and report on the M&E functions. It was reported that other government agencies, evaluation experts and voluntary organisations for professional evaluators collaborated in most aspects of national evaluation. The GWMES includes citizens in monitoring through CBM, thus mitigating the risk that cultural, social and physical barriers have on preventing citizens from contributing towards development, through the design and choice of CBM instruments. The design of CBMs takes into account social, cultural and physical barriers that may prevent the marginalised (elderly, women, disabled, youth, illiterate, immigrants, etc.) from giving their real views on service delivery. The CGE ensures gender-balanced participation. It was however established that, although the presence of gender focal persons is mandatory for all departments, these roles are often fulfilled by persons who are not gender experts and/or at levels with little influence and decision-making authority.

5.2.4 Sustainability

It was observed that, although gender-mainstreaming mandates and structures (as evidenced by the different policies and plans for the GWMES) are in place to support the gender responsiveness of the GWMES, the mainstreaming efforts were not yet implemented in the GWMES. Long-term sustainability of implementation was viewed as not measurable at the time of the study. The NEP and other GWMES activities had budgets for gender mainstreaming, which remain in the national budget in future. It was however perceived that the coordinated work needed to be done to engender the GWMES through funding from multi-stakeholders across departments, as it involves the DPME and DoW but also needs to include role players from private sector and CSOs.

6. Conclusion

The South Africa Government-wide National M&E System is well developed. The evolution of the system includes the incorporation of three key areas, each with a policy framework (GWMEPF, SASQAF, FMPPI and NEPF) and the present components of the national M&E system (including the outcomes system, MPAT, etc.). Gender mainstreaming is lacking in the South African public sector, and efforts seem to be fragmented at present. There is a lack of general gender skills for GFPs in particular. The policies and systems lack gender responsiveness. There are various strengths and opportunities that can enable the system to be more gender-responsive. These include political will and the strategic empowerment of the two main role-playing departments (DPME and DoW) as drivers of gender mainstreaming. Strategies include more immediate remedial actions such as the development of a gender responsiveness guideline/s, advocating for gender disaggregated data analysis and use, and the establishment of forums that will enhance the systems. There is need for multi-stakeholder engagement and commitment to gender mainstreaming. Longer-term strategies must focus on the revision of key documents and capacity development of key role players.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- AfrEA, 2017. Report on consultative meeting on NEPS. 8th AfrEA international conference, 27–31 March 2017, Kampala, Uganda.

- Andersen, M, 1993. The concept of mainstreaming: Experience and change. In Undersen, M (Ed.), Focusing on women: UNIFEM’s experience with mainstreaming, 1–32. UNIFEM, New York.

- Behning, U & Serrano Pascual, A, 2001. Rethinking the gender contract? Gender mainstreaming in the European employment strategy. In Gabaglio, E & Hoffmann, R (Eds.), European trade union yearbook. ETUL, Brussels.

- Beveridge, F, Nott, S & Stephen, K, 2000. Mainstreaming and the engendering of policy-making: A means to an end? Journal of European Public Policy 7(3), 385–405. doi: 10.1080/13501760050086099

- Braithwaite, M, 1999. Mainstreaming equal opportunities into the structural funds: How regions in Germany, France and the United Kingdom are putting into practice the new approach. Final report of the survey of current practice and findings of the seminar at Gelsenkirchen, January 21-22, 1999. Report produced for the European Commission, DG XVI (Regional Policy and Cohesion).

- Brisolara, S, 2014. Gender-sensitive evaluation: Best and promising practices in engendering evaluations. United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Maryland.

- Corner, L, 1999. A gender approach to the advancement of women: Handout and notes for gender workshop. UNIFEM East and South East Asia, Bangkok.

- DANIDA, 2006. Gender-sensitive monitoring indicators. Technical advisory service. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Copenhagen.

- De Orte, P, Segone, M, Da Costa Nogueira, lM, Tateossian, F & Nhlapo-Hlope, J, 2015. Challenges to integrating gender equality approaches into evaluation. The International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, No. 283, Brasilia.

- DoW, 2015. The status of women in the South African economy. Department of Women, Republic of South Africa, Pretoria.

- Engela, R & Ajam, T, 2010. Implementing a government-wide monitoring and evaluation system in South Africa. ECD Working Paper Series, No. 21.

- EvalPartners, 2016. Global evaluation agenda 2016–2020. EvalPartners. https://www.evalpartners.org/sites/default/files/documents/EvalAgenda2020.pdf Accessed 15 August 2017.

- GIZ, 2014. Guidelines on designing a gender-sensitive results-based monitoring (RBM) system. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Bonn and Eschborn, n.

- Goldman, I, 2016. CSO linkages on national M&E systems. Presentation at twende mbele NGO consultative meeting at africlassic river lodge, Rivonia Johannesburg, 8 March 2016.

- Goldman, I, Mathe, JE, Jacob, C, Hercules, A, Amisi, M, Buthelezi, T, Narsee, H, Ntakumba, S & Sadan, M, 2014. Developing South Africa’s national evaluation policy and system: First lessons learned. African Evaluation Journal 3(1), Art. 107, 9 pages.

- Jahan, R, 1996. The elusive agenda: Mainstreaming women in development. The Pakistan Development Review 35(4), 825–34.

- Karlsson, J, 2010. Gender mainstreaming in a South African provincial education department: A transformative shift or technical fix for oppressive gender relations? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 40(4), 497–514. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2010.490374

- Kwigisa, JC & Ssendiwala, EN, 2006. Gender mainstreaming in the university context: Prospects and challenges at makerere university, Uganda. Women’s Studies International Forum 29, 592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2006.10.002

- McKay, K, 2008. Good-Practice government systems for monitoring and evaluation. Independent Evaluation Group. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Moser, C & Moser, A, 2010. Gender mainstreaming since Beijing: A review of success and limitations in international institutions. Gender & Development 13(2), 11–22.

- OECD. 2000. Gender mainstreaming: Competitiveness and growth conference proceedings, Paris, 23-24 November. http://www.oecd.org/subject/gender_mainstreaming

- OECD, 2008. Gender and sustainable development: Maximising the economic, social and environmental role of women.

- Phillips, S, Goldman, I, Gasa, N, Akhalwaya, I & Leon, B, 2014. A focus on M&E of results: An example from the presidency, South Africa. Journal of Development Effectiveness 6(4), 392–406. doi: 10.1080/19439342.2014.966453

- Rai, SM, eds. 2003. Mainstreaming gender, democratising the state? Institutional mechanisms for the advancement of women. Manchester University Press, Manchester and New York.

- Rosenstein, B, 2013. Mapping the status of national evaluation policies: Commissioned by Parliamentarians Forum on Development Evaluation in South Asia jointly with EvalPartners.

- Sueng-kyung, K & Kyounghee, K, 2011. Gender mainstreaming and the institutionalization of the women’s movement in South Korea. Women’s Studies International Forum 34, 390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2011.05.004

- Talbot, C, 2010. Performance in government: The evolving system of performance and evaluation measurement, monitoring, and management in the United Kingdom. Independent Evaluation Group Communications, Learning, and Strategy (IEGCS), World Bank, Washington, DC.

- The Presidency, 2007. Policy framework for the government-wide monitoring and evaluation systems. Pretoria.

- Tinker, I, 1990. The making of a field: Advocates, practitioners and scholars. In Tinker, I (Ed.), Persistent inequalities: Women and world development, 27–53. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- True, J, 2003. Mainstreaming gender in global public policy. International Feminist Journal of Politics 5(3), 368–96. doi: 10.1080/1461674032000122740

- UN Women, 2015. How to manage gender-sensitive evaluation. Independent Evaluation Office.

- Unterhalter, E, 2007. Gender, schooling and global social justice. Routledge, Abingdon.

- Van Der Byl, C, 2014. Twenty year review: South Africa: 1994–2014: Background paper: Women’s empowerment and gender equality. The Presidency, Pretoria.

- Verloo, M, 2006. Mainstreaming gender equality in Europe: A critical frame analysis approach. The Greek Review of Social Research 117(B), 11–34.

- World Bank, 2012. Gender issues in monitoring and evaluation in agriculture. World Bank, Washington, DC.