ABSTRACT

In the South African context, the post-apartheid university is deemed a critical contributor towards the national development agenda and community engagement is a significant principle through which universities would bring about social and economic transformation. This is reflective of a growing global movement of networks of universities iterating the civic and social role of higher education and its responsibility to its place. Drawing on notions of place-making, this study briefly recalls the histories of the University of Fort Hare and the town of Alice and evidences the more contemporary engagement policy, design and praxis of both, to surmise the significance the university gives to its place. The findings reveal a disconnect between the University of Fort Hare and the town of Alice and conclude that whilst the University of Fort Hare remains the economic power in Alice, it has no intrinsic commitment towards either the town or place-making.

1. Introduction

Despite the longevity of the university as an institution of higher education, there remains little consensus as to what a university is for, whom it serves and where its future trajectory should lie. As McKenna (Citation2013:1) points out, ‘There is not even consensus as to whether a university is for the elite or for the masses, serves social development or economic growth, is a private good or a public one’.

Yet, and to the contrary, there is a growing global movement that argues that a university has a broader set of obligations to its host community and region. These obligations relate to social transformation and economic development, and community engagement is the means through which this would be achieved (Barnett, Citation2010; Watson et al., Citation2011; Butin & Seider, Citation2012; Benneworth, Citation2013; Wilson et al., Citation2015; CHE, Citation2016; Mtawa et al., Citation2016). As Goddard (Citation2011:viii) states:

Universities in the round have potentially a pivotal role to play in the social and economic development of their regions. They are a critical ‘asset’ of the region; even more so in less favoured regions where the private sector may be weak or relatively small, with low levels of research and development activity.

Exploring this emerging link between community engagement and place-making further, this paper examines the history, policies and engagement praxis of the University of Fort Hare and the town of Alice, and considers the degree to which the University of Fort Hare’s community engagement contributes to place-making.

2. University–community engagement and place-making

In the South African context, the post-apartheid university is deemed a critical contributor towards the national development agenda (DHET, Citation2010; NPC, Citation2012), and community engagement (CE) was established as a significant principle through which universities would participate in social and economic transformation (DoE, Citation1997).

There are numerous definitions of what CE in the context of higher education means. Wallis focuses on the mutuality between the university and community and goes on to stress that community engagement is ‘much more than community participation, community consultation, community service, and community development’ (Wallis, Citation2006:2). Bernardo et al. comment on the unidirectionality of notions of development and service and concede that CE is not only broader (and multi-directional) but also ‘a relationship which is framed by mutuality of outcomes, goals, trust and respect’ (Bernardo et al., Citation2012:188).

For example, Gaffikin et al. (Citation2008) define CE as follows:

[The engaged university is] based on equal exchange between academy and community, and rooted in a mutually supportive partnership that fosters a formal strategic long-term collaborative arrangement. Alongside a more systematic outreach by the university, it allows for the community’s ‘in-reach’ into the institution, whereby it can help transform the nature of the academy. (Gaffikin et al., Citation2008:102)

Whilst there are contestations as to what is meant by CE and the process by which CE becomes a systematic and strategic endeavour of the university (CHE, Citation2010), numerous studies have been emerging as to how the South African academy views, organises, and practises CE (Akpan et al., Citation2012; Kruss et al., Citation2012; Thakrar, Citation2015; CHE, Citation2016).

Yet, the meanings and understandings attributed to, and praxis of, university–community engagement vary widely and depend on the institution’s context, that is, its location, history and culture (Mulvihill et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, Reid argues that ‘community engagement and attention to “place” has proven to be a powerful tool’ (in Watson et al., Citation2011:236).

Place is both the social and the geographical, ‘a multi-dimensional concept including the natural world, the built environment, social relationships, economic relationships, patterns of interaction, as well as socially constructed meanings about each dimension’ (Thomas & Cross, Citation2007:38).

How a university relates to its place can be determined along the polarity between interdependent and independent. Additionally, how the university conceptualises itself as a social actor in relation to its locality determines the worth and well-being ascribed to its place. Thus, determining a university’s place-building entails: the description of the institution’s identity and how it values place, which in turn assists in reflecting on approaches to, and interactions with, the community; the prescription of place-building that is evident in the institution’s mission and policy intent; and the evaluation of place-making the institution undertakes relative to its role (Kimball & Thomas, Citation2012). Moreover, it is the programmes and catalytical activities that are integral to the creation and maintenance of place, in other words, the process of place-making (Richardson, Citation2015).

Thomas (Citation2004) assigns four benchmarks representing types of place-making organisations:

Transformational: the organisation is integrated with its place and identifies with its role of change agent;

Contributive: the organisation appreciates the importance of place and will invest in its well-being;

Contingent: the organisation sees itself as a stakeholder in the place; and

Exploitive: the organisation has no stake in the place and is independent.

Thus, it is both the core characteristics of CE and the relationship to place that frame this study of the University of Fort Hare in Alice.

3. The University of Fort Hare in Alice

After a series of Frontier Wars between the colonisers and the indigenes, the rural town of Alice emerged during the colonial period of South African history, first as a missionary station in 1824 and later as a town in 1852.

Whilst the idea of higher education for native South Africans had been aired as early as the 1880s by James Stewart, the then head of the Lovedale Mission Station (close to the town of Alice), it was formally proposed in the recommendations of the South African Inter-Colonial Native Affairs Commission in 1905. Whilst this proposal was borne through a missionary endeavour, there was considerable support (including financial) from the indigenous populations across the country, particularly as native South Africans wanting to embark on higher education had no option but to go overseas (Jabavu, Citation1920).

The supporters of a new university all agreed to select a site near Lovedale, though it was not until 1916 that the South African Native College (SANC) was opened, by the then Prime Minister, General Louis Botha. SANC was established on donated land, the former nineteenth-century military post Fort Hare; ironically, a space and place that, on the one hand, saw many bloody battles between colonisers and natives and on the other, became well known to natives across the country (and beyond) for the various native educational establishments located in the area (Matthews, Citation1957).

SANC’s first Principal, Dr Alexander Kerr, arrived at the end of 1915 from Scotland and SANC commenced in February 1916 with Dr Kerr and one native staff member, Davidson DT Jabavu, who had studied at the University of London. Before starting at SANC Jabavu had visited the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in America, under the directorship of its founder, Dr Booker T Washington.

Whilst both Kerr and Jabavu were strong advocates for higher education for native South Africans there were clear differences in what they thought a university should be for. Kerr’s speech given to the first cohort of students reflected his idea of a university as being ‘Not a building, or a group of buildings, magnificent or humble, but an association of students and teachers engaged in the pursuit of learning; an environment for the prosecution of study for its own sake’ (Kerr, Citation1968:37). His perspective suggested an institution independent of its place.

Quite the opposite to Kerr, Jabavu was speaking and writing about the gruelling everyday life of a black person, ‘Socially speaking, the black man in all public places is either “jim-crowed” or altogether ostracised’ (Jabavu, Citation1920:19). Jabavu felt that the agriculture extension work and farm demonstration he had seen at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (highlighting the technical advantage of modern industrialisation over rural primitiveness) could improve the well-being of communities and be replicated in South Africa. Through his vision of a university that invested in the well-being of its place, Jabavu launched several initiatives towards this endeavour. Though Morrow (Citation2006) argues that whilst such engagement activities could imply a strong relationship between SANC and its local communities, scientific-based approaches of agricultural systems were not really applied, nor was there evidence of any significant impact in the community. Nonetheless, Jabavu believed in a social role for the university, one that sought to resolve practical problems of its community, synonymous of the Land Grant university model conceived in America in the late nineteenth century (Bonnen, Citation1998; Thakrar, Citation2015).

Alongside the first few decades of SANC, with its growing student numbers, staff members, buildings and graduates, various Acts of Parliament were cumulatively building the ‘colour bar’ in everyday life and place for the native South African. The retirement of both Jabavu in 1944 and Kerr in 1948 (the same year that the National Party came into power), in many ways, marked the end of SANC’s non-racial era and the trajectory of the university’s CE activities that Jabavu had embarked upon. As Williams (Citation2001:21) states, ‘Fort Hare underwent a metamorphosis that changed its character and ethos’.

Although the town of Alice remained geographically isolated, the 1950s onwards saw both staff and students at the now University College of Fort Hare (UCFH) become further embroiled in the politics of the day. Of course, such activism did not endear UCFH to the white residents of Alice. Whilst institutional activities were tolerated by them, this was largely due to the economic dependency on the UCFH staff and students. During the 1950s, when the apartheid system deepened its hold on the country, Alice residents started to turn against the university, such that rhetoric to close UCFH and collaboration between the police and Alice residents became much more evident (Williams, Citation2001), all but branding UCFH as ‘not of its place’.

The pinnacle of the decade for UCFH, a snowballing effect of the re-conceptualisation of apartheid that sought to solidify white domination and power through the promotion of the Bantustan concept, where demarcated ethnically homogenous territories would be established to separate the races, started with the proposed Separate University Education Act of 1957. This was vehemently opposed by staff and students at UCFH together with several universities across the country. Regardless of the united objection, UCFH lost its battle against its reclassification to a black-Xhosa-only university. In addition, in 1961 Alice became part of the newly formed Ciskei Bantustan that in 1972 was awarded self-governing status and in 1981 made ‘independent’; Ciskei had its own flag and President.

Thus, UCFH from the 1960s onwards became a state tool to build a ‘nation within a nation’; its only stake in its place was producing graduates that would service the administrative needs of Ciskei (its Bantustan) and alongside this mould intellectuals that would channel their energies into the homelands (Beale, Citation1992).

In 1970 UCFH became autonomous and received full university status and was renamed University of Fort Hare (UFH). Regardless of the segregation implemented ‘the expropriation of Fort Hare failed to produce the docile and isolated group of students desired by government’ (Massey, Citation2010:204). Indeed, the 1970s through to the 1990s was a continued period of anti-apartheid unrest at the university and as a result, UFH leadership made no attempt to continue linkages with its communities as it feared collective militancy and did not see the community as anything beyond a source for labour (Nkomo et al., Citation2006). This university position, as independent of its place, was reinforced by the state-appointed UFH leadership, which was determined to keep UFH independent of Alice and its surrounds.

By the end of apartheid territorial reconfiguring of the new South Africa determined nine provinces and Alice later formed part of the Nkonkobe Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province. By now, UFH was largely seen as ‘Bantu college’ that provided substandard education, its colonial and apartheid legacies of poor funding, underdevelopment, and disintegrated community linkages caused UFH, over the period 1994–9, to slip into rapid decline (Swartz, Citation2006). By the end of 1999, a backlash from within and without the university, followed by the recommendations of the Saunders Report (DoE, Citation1999), led to the overhaul of the university leadership team.

With its new leadership team now in place, the institutional turnaround strategy, as presented in UFH’s Strategic Plan 2000 (SP2000), was the first time its intention towards its local communities was clearly stated:

The UFH also seeks to position its vision and mission within the context of the need to make a distinctive and definitive contribution to the development challenges of our nation as it seeks to improve living and working conditions. This is especially crucial if we are to attract both students and staff to Alice, whose rebuilding and development … is a sine qua non, for the achievement of the strategic development of the UFH itself. (UFH, Citation2000:16)

Whilst SP2000 echoed the rhetoric of the ‘developmental’ university that emerged from East Africa some 40 years earlier (Court, Citation1980), it became stifled and perhaps short-lived by the sweeping changes to the higher education landscape. That is, the resizing and reshaping of universities in South Africa, which resulted in UFH incorporating the Rhodes University East London campus (January 2004).

The UFH strategic attention that was solely Alice-biased was now divided. Incorporating a new campus in a city, some 120 kilometres from Alice, brought about a flurry of activity regarding the spatial, intellectual, social, and physical opportunities now unlocked.

UFH was required by the national government to prepare an Institutional Operating Plan (IOP), which would present its new academic structure and recommend its strategy for incorporation and growth as a multi-campus university (UFH, Citation2004). Its development provided UFH with an opportunity to reflect on its progress since SP2000 and interestingly it determined that challenges of ‘place’ and deficient ‘capital’ had prevented the university from meeting its development goals:

UFH has not yet been able to fully exploit its strategic potential in serving national development goals – given its historic legacy, institutional location and strategic disposition … Put simply, we are not sufficiently capitalized to meet the challenges of regional and national development as set out in SP2000. (UFH, Citation2004:3)

One thing that has struck me is that our institution, which … has produced some of the most outstanding leaders in politics, business, culture and so on … Yet, when you look at the immediate environment of the university you would hardly notice its impact … it seems shameful, indeed unacceptable, that we have made limited impact on our immediate surrounds. Something must be done about this. (Swartz, Citation2006:1)

It is important to note that community engagement is not exclusively a rural issue, but the Fort Hare context compels it to take special interest in its immediate and historic surrounds … Beyond material poverty, the great majority of South Africans have traditionally had little access to, or influence over, university life, nor have universities been fundamentally oriented towards their requirements. (UFH, Citation2009:36)

Accordingly, Nkonkobe Municipality’s 2012–17 Integrated Development Plan (IDP) highlights as its strategic framework four pillars for social and economic development: agriculture, tourism, the government/social sector and the business sector (Nkonkobe Municipality, Citation2011). Within the government/social sector, the IDP states as its sub-strategy, a ‘strategic partnership with UFH’ (Nkonkobe Municipality, Citation2011:61). Yet, within the 242-page-long IDP, there is no mention of just what that means, what steps need to be taken, and by whom.

In 2009, the Nkonkobe Development Agency (established in 2002 by the Nkonkobe Municipality) embarked on the Alice Regeneration Project with a steering committee made up of representatives from UFH, provincial and local government and various stakeholders and individuals from the town of Alice. The vision is to make Alice ‘a socially and economically viable university town’ (Apsire, 2011:10) and the following extract from the regeneration strategy reveals what was envisaged:

As a university town, Alice is a place of debate, which fosters a culture of exchange and continuous learning. As an African University Town, Alice also becomes about ‘taking on a cause’, being part of ‘civic’ happening, and making a meaningful contribution to the real empowerment of the disadvantaged and poor … It is therefore important that the UFH and other academic institutions, as well as their students and staff, be viewed as a key part of the Alice community. Measures should be put in place to integrate both spatially and socially, UFH and Lovedale with Alice town. (Aspire, Citation2011:10)

So, whilst the strategic intent of UFH (SP2009) ambiguously identifies that there is a need for specific engagement with ‘its immediate and historic surrounds’, it does not clearly articulate an intent towards Alice. Yet, the strategy for the regeneration of Alice clearly recognises the significance of UFH. This significance is threefold:

UFH as an institution of higher learning, its brand, identity and historical import;

Alice-based UFH staff and students and the social and economic importance of their presence; and

The intellectual, physical and financial resources that UFH can access.

The Alice-led regeneration strategy clearly recognises that its development rests on the town’s ability to assimilate with UFH.

4. Community engagement as place-making?

4.1. Praxis

In 2010, together with four other South African universities, UFH was selected as the rural-based university for a pilot study conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). The project sought to map the scale and forms of university linkages with community-based and social partners, to problematise the changing role of the university (Kruss et al., Citation2012).

The methodology adopted included a telephonic survey with individual academics, followed by a sample of face-to-face interviews with various role players within and without the institution. The survey instrument sought to investigate five different aspects of engagement:

The nature of external social partners;

Types of relationships;

Channels of interaction;

Outcomes and benefits of interaction; and

The challenges of and constraints on interaction.

Out of a total of 278 UFH academics, telephonic interviews were conducted with 174 or 63% of the total population. The telephone survey began with a question relating to engagement and the kinds of social partners. Out of the 174 surveyed, 24 respondents immediately announced that they do not engage with anyone. A remarkable confession to make considering the UFH academic promotion policy, which requires evidence of CE involvement (UFH, Citation2010).

Maybe not so surprising is that the main external social partner for academics interviewed across all five universities in the study was another South African academic. Reflective perhaps of, on the one hand, what academics know and understand are other academics, and on the other hand, the pressure to ‘publish or perish’ predicates such engagements to be critical.

Interestingly, the two main differentials between UFH and the total university sample were first the HSRC category of ‘a specific local community’ being the second choice of external social partner for academics at UFH. Secondly, three categories of external social partners: large South African firms; science councils; and small medium and micro enterprises were not in the UFH top 10 categories of external social partners.

In terms of questions relating to the ‘why’ of engagement, for all universities, the primary type of relationship was one that related to the education of the student. Indeed, most of the top 10 types of engagement were either to benefit student learning or to the benefit of the academy.

In relation to the kinds of outputs and outcomes sought from the engagement, the top five categories selected by all five universities included:

Graduates with relevant skills and values;

Academic collaboration;

Dissertations;

Academic publications; and

Reports, policy documents and popular publications.

The HSRC study illustrates UFH engagement praxis as unidirectional, from the university to the community, and overall to the bias of the university. In addition, though UFH self-identifies as an engaged university (SP2009), the actual work of the academic and the priorities given to teaching and research are the same regardless of any perceived differentiation. Is this demonstrative of Collini’s (Citation2012) argument that universities have lost their distinctiveness in that their local or practical characteristics have eroded, a melding and merging process that has resulted in universities, despite the ways in which they self-describe, becoming the same?

Alongside the HSRC study and concluding in 2010, the then Deputy Vice-Chancellor led an academic review process, which required every academic department, centre, institute and project (DCIP) to produce a self-evaluation report using the guidelines provided by the institutional quality assurance unit. An analysis of 38 self-evaluation reports (Thakrar, Citation2010) determined that whilst there was evidence that every DCIP was involved in CE in some shape or form:

The dominant types of CE were outreach programmes and service learning, which are unidirectional in nature;

Little emphasis was placed on the ‘mutually beneficial’ aspects of CE and so whilst both community and university may benefit from the engagement, they do so separately;

No coherent body of CE initiatives existed and so there was poor synergy between and across DCIPs; and

A lack of strategic CE policy direction and resource commitment by UFH continued to impede CE development.

4.2. Design

The distance from the main entrance to UFH and the outskirts of Alice town is some 800 metres. Yet, more than the physical, there appears a metaphorical distance as the Alice Regeneration Project strategic priorities include the integration of UFH and Alice, both in terms of the physical, the movement of UFH staff and students in and amongst the Alice town (and vice versa), and as strategic, the interdependency of Alice and UFH (Aspire, Citation2011). Ironically then, on entering Alice via the main route, the provincial R63 road shows the municipal-erected welcome sign ( below), which illustrates no mention of Alice as a university town, in fact, the sign reveals nothing of the presence of UFH.

So, from the perspective of the Alice Regeneration Project the sign fails to convey the town’s strategic vision, indeed, it fails to reveal to the traveller anything beyond its name. Ironically, the previous sign, which was in the form of a tall and colourful billboard, read ‘Welcome to Alice, the home of the University of Fort Hare’, whereas the current sign is grave-like, a sombre commemoration of what Alice perhaps once was, or even worse, continues to be.

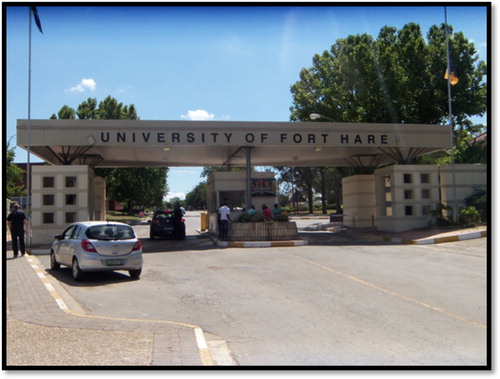

Comparably, when considering the spatial and physical identity of UFH as conveyed to the visitor from the town of Alice, particularly those travelling on foot (the main mode of transport in Alice), the following illustrates what such a journey would entail.

The portrayal of the journey from Alice to UFH begins with above, which depicts the bridge over the Thyume River that links UFH to the town of Alice. It has a walkway for those travelling by foot. As one crosses the bridge the first glimpse of the university shows a fence (see below), a physical border-building between the institution and its surrounds.

Finally, one arrives at the overwhelming entrance to the institution with its security stations, security personnel and boom gates controlling who comes in and goes out (see below). Is this UFH as a gated community, physically and socially segregating its community of staff and students from the town of Alice? Beyond the entrance, there exists no signage of what is where on the campus; the visitor who seeks some form of ‘in-reach’ would be lost.

Thus, beyond recognising the fact that South Africans have not traditionally had access to, or influence over the university (UFH, Citation2009), the university has done little to make that access realisable. If the visitor to UFH was not aware of whom they needed to meet with and where exactly they resided on campus, the physical and spatial identity of UFH does little to assist or direct. In fact, it could result in the opposite occurring, in that the fencing, the border-building and the imposing entrance could detract someone from reaching-in. Similarly, these physical borders could serve as protection for the ‘community within’ UFH, its staff and students, who are close to but not a part of Alice.

4.3. Public discourse

Daily Dispatch (DD), a newspaper founded in 1872, has reported on UFH since its establishment and throughout its various evolvements thereafter (Williams, Citation2001; Massey, Citation2010).

A search of the DD digital archive on 12 March 2014 of articles available since September 2003, using the criterion ‘University of Fort Hare’, revealed 2263 articles. Three hundred and four articles were identified as specifically relating to UFH and an analysis of these shows three dominant threads of public discourse in relation to place-making, which whilst not entirely linear in terms of reporting periods, as there is overlap, have significant periods in which they occur (Thakrar, Citation2015).

The first thread relates to news on UFH’s community engagement framed within a developmental agenda, which even after the incorporation of Rhodes University East London (EL) campus, focused almost entirely on Alice, ‘This grant gives impetus to ongoing attempts by the University of Fort Hare to make a valuable contribution to the communities around’ (Daily Dispatch, Citation2004).

The second thread, which began with concerns relating to UFH’s capability of incorporating a previously ‘white’ university campus in EL ironically shifted to the social and economic opportunities of an expanded EL campus, ‘R150 m to kickstart EL “student city” plan’ (Daily Dispatch, Citation2007). This discourse continued into more contemporary discussions of UFH in EL, ‘Support for UFH long-range plan will give East London economy impetus it needs’ (Bank & Mills, Citation2013).

The third thread correlates with the increasing prominence given to the EL campus as the idea of UFH as ‘a developmental university’ gives way to UFH as ‘an engaged university’. This can be demonstrated by the UFH/DD dialogues, which began in December 2007 with a debate and book launch that was open to the public and hosted on the EL campus. This event inspired a series of UFH/DD dialogues; by September 2012, 73 dialogues had been hosted, alternating between UFH EL campus and the East London Guild Theatre as host sites, and some 25 000 members of the public have attended; the 90th dialogue was hosted on 13 February 2014.

Where Alice had become synonymous with the ‘developmental agenda’ of SP2000, the UFH/DD dialogues reflect the SP2009 ‘engaged agenda’ as DD reports, ‘Based on the “town hall” concept, these dialogues are designed to give our readers a chance to have their say and become active citizens’ (Daily Dispatch, Citation2009). Yet, these dialogues are confined to EL, the urban.

Consequently, the public discourse of Alice began to, on the one hand, question the university in the rural, ‘it remains to be seen whether turning Alice into a university town is feasible, however, as UFH plans to shift its further growth to East London’ (Daily Dispatch, Citation2008), and on the other hand emphasises Alice’s placelessness, ‘the down-trodden little town’ (Daily Dispatch, Citation2011), which requires national government intervention, ‘Fort Hare vice-chancellor Dr Mvuyo Tom used the opportunity to call on the government to invest more in development of Alice’ (Daily Dispatch, Citation2012).

5. The (in)significance of Alice

The brief recall of UFH and Alice history reveals the points at which the disconnect between the university and the town was most prominent and acknowledges that the apartheid system was a major factor towards separating the ‘gown’ from the ‘town’. Yet, in the post-apartheid period, UFH’s own reflection of SP2000 admitted it had made no real impact in Alice and since UFH emerged as a multi-campus institution, SP2009 fails to demonstrate a definitive CE strategy, in other words, its intention towards its place(s).

Moreover, the HSRC study reveals that the UFH CE practices are more about enhancing the institution as opposed to any form of place-making. Similarly, whilst the academic review process determined that academics (across all campuses and DCIPs) are involved in CE, the predominately unidirectional forms of engagement practices suggest that UFH does engagement to its community as opposed to with its community.

Notwithstanding the Alice Regeneration Project stipulation that social and spatial integration with UFH is its intent, its own border marking fails to self-identify Alice as a place of significance, as a ‘university town’. Likewise, despite the near proximity of UFH to the town of Alice, UFH’s physical border of its fencing and security-driven entrance prevents any form of community in-reach: place-based knowledge that could enhance the academy.

In considering then the university’s context, its strategic intent and praxis of CE in Alice, and referencing Thomas’ (Citation2004) typology of place-making institutions (as presented above), clearly, UFH has not demonstrated any transformational practices or outcomes. A lack of any systemic or strategic CE intent that is supported by adequate resources is indicative of UFH not being contributive towards its place. Rather, whilst its historical legacy is that of an exploitive institution, certainly, its contemporary rhetoric implies UFH as a contingent university. That is, a university that has a separatist strategy, one that identifies UFH as the economic power with its various resources, but without any intrinsic commitment to its place. UFH does not identify itself as interdependent with Alice, rather it sets itself apart.

Significantly, January 2017 saw the investiture of a new Vice-Chancellor at UFH and the following extract from his official opening of the academic year gives insight into his vision of the future role of UFH:

The purpose of the University is to teach and to do research … the position of Alice as the main campus is undisputed … The decrepit condition of Alice makes it difficult for it to fulfil its role [of] a University town … It is imperative that we … join hands to regenerate the town … Finally, the links of the University to the surrounding communities seems to be limited … It is my view that a significant proportion of the research conducted by the University should address itself to the issues experienced by the communities. (Buhlungu, Citation2017)

On 2 November 2017, the Vice-Chancellor signed a new Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) between UFH and the renamed Raymond Mhlaba Municipality (created from the merger of Nkonkobe and Nxuba municipalities). The event marked the recognition that, despite its rich cultural heritage, Alice had failed to live up to the expectations of a university town. As the Vice-Chancellor stated, ‘it’s scandalous that the town has been allowed to go so derelict … if Alice grows we grow, if it goes down, we go down’ (UFH, Citation2017).

It remains to be seen then, whether this new MoA will serve as a catalyst to re-conceptualising how UFH engages with its place or it simply garners more of the same, that is, CE activities that are transactional and biased to the academy as opposed to transformational and place-making (Seedat, Citation2012).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Akpan, W, Minkley, G & Thakrar, J, 2012. In search of a developmental university: Community engagement in theory and practice. South African Review of Sociology 43(2), 1–4. doi: 10.1080/21528586.2012.694239

- Aspire, 2011. Alice small town regeneration strategy report. Aspire, East London.

- Bank, L and Mills, G, 2013. Building a better life. Daily Dispatch, 16 March 2013.

- Barnett, R, 2010. Being a University. Routledge, London and New York.

- Beale, MA, 1992. The evolution of the policy of university apartheid. Collected Seminar Papers, Institute of Commonwealth Studies 44, 82–98.

- Benneworth, P, 2013. University engagement with socially excluded communities. Springer, Heidelberg.

- Bernardo, MAC, Butcher, J & Howard, P, 2012. An international comparison of community engagement in higher education. International Journal of Educational Development 32(1), 187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.04.008

- Bonnen, JT, 1998. The land grant idea and the evolving outreach university. In Lerner, RM & Simon, LK (Eds.), University-community collaborations for the twenty-first century: Outreach scholarship for youth and families. New York, Garland, 25–70.

- Buhlungu, S, 2017. Official opening of the 2017 academic year and welcome to staff and students, 2 February 2017, Alice. http://www.ufh.ac.za/files/Official%20Opening%202017.pdf Accessed 27 February 2017.

- Butin, DW & Seider, S, 2012. The engaged campus. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

- CHE (Council on Higher Education), 2010. Community engagement in South African higher education. Government Printers, Pretoria.

- CHE (Council on Higher Education), 2016. South African higher education reviewed: Two decades of democracy. Government Printers, Pretoria.

- Collini, S, 2012. What are universities for? Penguin Books, London.

- Court, D, 1980. The development ideal in higher education: The experience of Kenya and Tanzania. Higher Education 9(6), 657–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02259973

- Daily Dispatch, 2004. R5m for Ft Hare Nguni Project, 30 April 2004.

- Daily Dispatch, 2007. R150m to kickstart EL ‘student city’ plan, 4 April 2007.

- Daily Dispatch, 2008. Alice calls consultants for renewal proposals, 7 August 2008.

- Daily Dispatch, 2009. Dispatch dialogues, 18 March 2009.

- Daily Dispatch, 2011. Planting the seeds of prosperity, 4 October 2011.

- Daily Dispatch, 2012. Zuma wants to help build SA, 25 May 2012.

- DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training), 2010. Report on the stakeholder summit on higher education transformation, 22–23 April 2010, Centre for Education Policy Development, Cape Town.

- Diaz Moore, K, 2014. An ecological framework of place: Situating environmental gerontology within a life course perspective. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 79(3), 183–209. doi: 10.2190/AG.79.3.a

- DoE (Department of Education), 1999. Government gazette, volume 405, number 19842. Government Printers, Pretoria.

- DoE (Department of Education), 1997. Education white paper 3: A programme for higher education transformation. Government Gazette No 18207. Government Printers, Pretoria.

- Gaffikin, F, McEldowney, M, Menendez, C & Perry, D, 2008. The engaged university. Queens University, Belfast.

- Garlick, S & Palmer, VJ, 2008. Toward an ideal relational ethic: Re-thinking university-community engagement. Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement 1, 73–89. doi: 10.5130/ijcre.v1i0.603

- Goddard, J, 2011. Connecting universities to regional growth: A practical guide. European Union, Brussels.

- Herts, RD, 2013. From outreach to engaged placemaking: Understanding public land-grant university involvement with tourism planning and development. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 17(1), 97–111.

- Jabavu, DDT, 1920. The black problem. Lovedale Press, Lovedale.

- Kerr, A, 1968. Fort hare 1915–1948: The evolution of an African college. C Hurst and Co, London.

- Kimball, JM & Thomas, DF, 2012. Place-building theory: A framework for assessing and advancing community engagement in higher education. Journal of Community Service Learning 18(2), 19–28.

- Kruss, G, Visser, M, Aphane, M & Haupt, G, 2012. Academic interaction with social partners: Investigating the contribution of universities to economic and social development. HSRC, Cape Town.

- Massey, D, 2010. Under protest: The rise of student resistance at the university of fort hare. UNISA Press, Pretoria.

- Matthews, ZK, 1957. The university college of fort hare. The South African Outlook, April-May, 1–35.

- McKenna, S, 2013. Introduction in the aims of higher education, Kagisano number 9. Council on Higher Education. Lovedale Press, Pretoria.

- Moore, TL, 2014. Community-university engagement: A process for building democratic communities. ASHE Higher Education Report 40(2), 1–129. doi: 10.1002/aehe.20014

- Morrow, S, 2006. Fort hare in its local context: A historical view. In Nkomo, M, Swartz, D & Botshabelo, M (Eds.), Within the realm of possibility: From disadvantage to development at the university of fort hare and the university of the north. HSRC Press, Cape Town, 85–103.

- Mtawa, NN, Fongwa, SN & Wangenge-Ouma, G, 2016. The scholarship of university-community engagement: Interrogating Boyer’s model. International Journal of Educational Development 49(2016), 126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.01.007

- Mulvihill, N, Hart, A, Northmore, S, Wolff, D & Pratt, J, 2011. The future of community-university engagement: South east coastal communities dissemination paper 1, May. University of Brighton, Brighton. www.coastalcommunities.org.uk/briefingPapers.html Accessed 19 January 2014.

- Nkomo, M, Swartz, D & Botshabelo, M (Eds.). 2006. Within the realm of possibility: From disadvantage to development at the university of fort hare and the university of the north. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Nkonkobe Municipality, 2011. Integrated development plan 2012–2017. Nkonkobe Municipality, Fort Beaufort.

- NPC (National Planning Commission), 2012. National development plan 2030: Our future – Make it work. Government Printers, Pretoria.

- Richardson, A, 2015. Fostering community through creative placemaking. Master’s Thesis. http://scholars.wlu.ca/brantford_sjce/10/ Accessed 16 November 2016.

- Seedat, M, 2012. Community engagement as liberal performance, as critical intellectualism and as praxis. Journal of Psychology in Africa 22(4), 489–500. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2012.10820560

- Swartz, D, 2006. New pathways to sustainability: African Universities in a globalising world. In Nkomo, M, Swartz, D & Botshabelo, M (Eds.), Within the realm of possibility: From disadvantage to development at the university of fort hare and the university of the north. HSRC Press, Cape Town, 127–166.

- Thakrar, JS, 2010. Academic review process: Reflections on community engagement at the University of Fort Hare. Unpublished internal document.

- Thakrar, JS, 2015. Re-imagining the engaged university: A critical and comparative review of university-community engagement. unpublished doctoral thesis. University of Fort Hare, South Africa.

- Thomas, DF, 2004. Toward an understanding of organization place building in communities. unpublished doctoral dissertation. Colorado State University, Fort Collins.

- Thomas, DF & Cross, JE, 2007. Organizations as place builders. Journal of Behavioural and Applied Management 9(1), 33–61.

- UFH (University of Fort Hare), 2000. Strategic plan 2000. University of Fort Hare, Alice.

- UFH (University of Fort Hare), 2004. Institutional operating plan. University of Fort Hare, Alice.

- UFH (University of Fort Hare), 2009. Strategic plan 2009–2016: Towards our centenary. University of Fort Hare, Alice.

- UFH (University of Fort Hare), 2010. Promotions/appointments of academic and research staff policy document. University of Fort Hare, Alice.

- UFH (University of Fort Hare), 2017. @UFH1916 VC and Mayor Raymond Mhlaba municipality signing MoA, 2 November 2017. https://twitter.com/ufh1916 Accessed 11 November 2017.

- Wallis, R, 2006. What do we mean by “community engagement”? Paper presented at The Knowledge Transfer and Engagement Forum, June 15-16, Sydney, Australia.

- Watson, D, Hollister, R, Stroud, S & Babcock, E, 2011. The engaged university: International perspectives on civic engagement. Routledge, London.

- Westaway, A, 2012. Rural poverty in the eastern cape province: Legacy of apartheid or consequence of contemporary segregationism? Development Southern Africa 29(1), 115–25. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2012.645646

- Williams, D, 2001. A history of the university college of fort hare, South Africa-The 1950s: The waiting years. The Edwin Mellen Press, Lampeter.

- Wilson, C, Manners, P & Duncan, S, 2015. Building an engaged future for UK higher education. https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publication/t64422_-_engaged_futures_final_report_72.pdf Accessed 31 October 2016.