ABSTRACT

In South Africa, scholars and practitioners do not sufficiently appreciate the value of parks, libraries and sport and recreation facilities for uplifting lower-income areas, and are generally unaware of the subtle differences between providing these facilities in a northern country and providing them in a southern country. This paper addresses these concerns by demonstrating the importance of these facilities for developing social capital and empowering individuals and communities. It argues that the success of such facilities depends on sensitivity to the community’s need for safe spaces. The paper is based on a case study of the Mahwelereng Sports Node & Library in Mokopane, Limpopo Province, using document analysis and interviews and discussions with the facility’s developers, managers and users. It was found that the activities offered by the facility had boosted the local community’s social capital and improved the users’ health, learning and socialisation.

1. Introduction

Since 2006, funding for township renewal in non-metropolitan areas of South Africa has been provided by the National Treasury, in the form of the Municipal Infrastructure Grant (MIG) and the Neighbourhood Development Partnership Grant (NDPG). These grants include funds for parks, libraries and sport and recreation facilities, which form part of the broader category of ‘community services’. The NDPG aims to ‘support neighbourhood development projects that provide community infrastructure and create the platform for private sector development and that improve the quality of life of residents in targeted areas’ (quoted by Pernegger & Godehart, Citation2007:2). Similarly, the MIG has included funding for community facilities in its grant allocations, based on the premise that these facilities are part of the essential basic services that every South African should have access to (DPLG, Citation2004).

However, according to the Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (COGTA, Citation2015), these grants are currently being underutilised, for reasons such as lack of municipal capacity to administer the funding and uncertainty about how to implement the planned projects. Furthermore, COGTA (Citation2015) says that funds allocated to sport and recreation facilities have been redirected by municipalities to other priorities that they see as more important.

In this paper we emphasise the importance of parks, libraries and sport and recreation facilities in previously disadvantaged areas. We show that these amenities can improve township residents’ quality of life by offering a safer environment for recreation, enabling learning and personal development, creating the conditions for improved health and transforming a township’s sense of place. We stress that it is possible for a small municipality with a limited budget to develop a multi-use and multi-age facility that promotes township residents’ social and personal development.

2. Literature review

The following is a broad overview of the literature on parks and public open spaces, libraries and sport and recreation facilities in South Africa. We focus on empirical studies and the role that these facilities play in low-income areas.

2.1. Parks and public open spaces

The small amount of literature on public open spaces in South Africa presents contrasting views, illustrating on the one hand the residents’ distrust of such spaces and on the other their need for them. As an example of distrust, Mashalaba (Citation2013) showed that what is on the whole true of parks and open spaces in the developed world – in particular, the way they improve social integration and quality of life (Thompson, Citation2002) – did not hold true for the township of Galeshewe, Kimberley, where residents considered open spaces dangerous, seeing them merely as vacant land left open for future development rather than valuable spaces for recreation. Perry et al. (Citation2008) and Pillay & Pahlad (Citation2014) reported similar findings, and particularly that these spaces were viewed as crime hotspots. Furthermore, Statistics South Africa’s ‘victims of crime’ survey for 2014/15 found that the most cited answer (by 36.9% of the sample) to the question about which activities respondents were prevented from doing because of crime was ‘going to open spaces or parks’ (Stats SA, Citation2015: Figure 8).

This distrust of public open spaces has been noted in a few international studies (for example Groff & McCord, Citation2012; Kimpton et al., Citation2017), but it is far less common for them to be seen as dangerous or as crime hotspots in northern countries. In South Africa, by contrast, this seems to be the prevalent view, at least in low-income areas.

Some of the literature on public open spaces in South Africa argues that there is a need for safe and attractive public open spaces that might help to overcome this distrust. Massey (Citation2013) found a breakdown in social connections between households that had been moved to newly constructed subsidised housing developments in Makhaza and New Rest in Cape Town and argued that this was largely because these townships lacked public meeting spaces. In Malvern, Johannesburg, Kruger & Chawla (Citation2002) found that children were unhappy about the open field behind their school because it was neglected, covered in litter and unsafe because it was used as an informal drinking spot. And Shackleton & Blair (Citation2013) found that residents of the towns of Fort Beaufort and Port Alfred in the Eastern Cape valued open spaces, and that the more green space available, the greater was the usage.

Willemse & Donaldson (Citation2012) found that community neighbourhood parks in five areas of Cape Town were appreciated but there were too few of them, and those that did exist lacked facilities. They noted that the best ways to improve the parks were to supply security guards, install CCTV cameras and provide more and safer play equipment. McConnachie & Shackleton (Citation2010), investigating green space in nine South African small towns (mostly in the Eastern Cape), found that the percentage of open space was 3.6% in public housing developments, 12% in old townships and 11.8% in affluent areas. In other words, post-apartheid low-income developments had significantly less open space than apartheid-built townships and affluent areas.

2.2. Libraries

The central issue in the literature appears to be the tension between the traditional role of libraries as repositories of information and their interventionist role as agents of social development. Libraries in South Africa’s middle-income areas in particular continue to perform their traditional function, which is:

to acquire, organise, offer for use and preserve publicly available material irrespective of the form in which it is packaged (print, cassette, CD-ROM, network form) in such a way that, when it is needed, it can be found and put to use. (Ryynänen, Citation1999:1)

In contrast, libraries in the low-income areas are starting to play an interventionist role, to assist community members of all ages with learning and literacy (Hart, Citation2006, Citation2010, Citation2012; Denoon-Stevens, Citation2007; Nassimbeni & Tandwa, Citation2008; Mnkeni-Saurombe, Citation2009; Nassimbeni & May, Citation2009; Hart & Nassimbeni, Citation2014). To quote Stilwell (Citation2006), as summarised by Mnkeni-Saurombe & Zimu (Citation2013:45), community libraries can play a role in:

Social cohesion – by providing a meeting place and centre of community development, raising the profile and confidence of marginalised groups;

Community empowerment – by supporting community groups and developing a sense of equity and access;

Local culture and identity – by providing community identity and information;

Health and well-being – by contributing to the quality of life and how well people feel and by providing health information services;

Personal development – including formal education, lifelong learning and training, after-school activities, literacy, leisure, social and cultural objectives through book borrowing, skills development and availability of public information; and

Local economy – by providing business information and supporting skills development.

A notable example of this is documented by Hart (Citation2012), who found that a single library in Site B in Khayelitsha, Cape Town had a network of 75 volunteers and reached 34 000 participants through its various projects in a single year.

However, not every community library is playing this role: Nassimbeni & May (Citation2009) note that only 26.7% of libraries in South Africa were offering adult education at the time of their study. One difficulty is that while this social empowerment role is needed in arguably most low-income communities, official recognition of the role is lacking, making some librarians uncertain about the role’s legitimacy (Hart, Citation2006). Another is that the criteria used to measure the performance of the community library conditional grant are the numbers of different kinds of reading material provided, libraries upgraded or built and staff employed, but no mention is made of social empowerment or community development (DAC, Citation2015a). That said, there has been an encouraging growth in the funding for and number of libraries providing information and communication technology (ICT) and free internet access, and the provision of toys for toy libraries (DAC, Citation2015b).

2.3. Sport and recreation facilities

Most of this literature argues that more sport facilities (other than open fields) are needed in low-income areas (Ngcobo, Citation1998; Sibeko, Citation2007; Simelane & CJCP, Citation2011) and that they can facilitate social integration and reconciliation and help township youth to avoid getting drawn into the negative aspects of township life such as substance abuse and crime (Keim, Citation2003; Höglund & Sundberg, Citation2008; Swart et al., Citation2011; Whitley et al., Citation2016).

A few authors have expanded this basic argument. Ngcobo (Citation1998), Denoon-Stevens (Citation2007) and Brangan (Citation2012), for example, have pointed out the inadequacy of considering sporting facilities on their own, and the importance of ensuring that the facilities are accessible and affordable and provide coaching and programmes. A weakness in the literature is that most studies have relied on respondents’ perceptions. A notable exception is Redpath’s quantitative study (Citation2010) of the risk factors for victimisation in Kimberley in the Northern Cape, using a sample of 800 respondents, which found that, for men, participating in sports led to a 47% increase in the rate of victimisation. Although the study looked at only one township, it nevertheless challenges the perception that increased participation in sports leads to a reduction in crime.

In sum, the literature on parks and public open spaces, libraries and sport and recreation facilities in South Africa indicates that the main characteristics and roles of these facilities in low-income areas differ from those in the middle- to upper-income areas and from those in developed countries. In particular, parks and public open spaces, while still needed, tend to be perceived as being dangerous in this country (at least in low-income areas). Libraries play a stronger interventionist role in supporting community and learner development. Sport facilities are important both for recreation and for community development and personal empowerment.

3. Method

Our study of the Mahwelereng Sports Node & Library (MSNL) in Limpopo Province used qualitative methods and a case study research design, supported by document analysis. We conducted it during a two-week period in June and July 2015, to take advantage of the winter vacation when most members of the community were around. We conducted unstructured interviews and informal discussions with 8 key informants, 11 individuals and 5 groups. The key informants were municipal officials, the individuals were users of the facility and various private professionals involved in the development of the facility and the groups were a soccer team (22 people), a basketball team (5), an aerobics club (12), a cricket team (12) and the maintenance team (10).

The individuals and groups were selected through convenience sampling techniques. Specifically, the municipal officials were identified through discussions with the municipal town planner, and the landscape architect was identified from the site plans and interviewed via email. The remainder of the individual and group interviews were arranged by visiting the site and approaching the staff and users of the facility. To capture the full spectrum of views, we endeavoured to meet the majority of the staff working at the facility and users at each of the various amenities.

To supplement the findings from the interviews and groups, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the municipal integrated development plans (IDPs) for the years 2010–12, when the MSNL was being planned and built.Footnote1 These documents provided valuable information on the process and cost of the development. To integrate the material from the interviews, discussions and document analysis, we identified broad themes running through it, which we expand on in the rest of the paper.

4. The Mahwelereng Sports Node & Library (MSNL)

4.1. Events preceding the creation of the MSNL

The site was initially zoned as ‘undetermined’ when the township of Mahwelereng was established. Over time, like many other open spaces in South Africa, it became an illegal dumpsite. The municipality then intervened and turned it into a formal landfill site to try and control it (Head of Planning Division, 2015, personal communication). The dump became operational around the 1980s and remained like that for close on 24 years. Then a study by Mashiteng (Citation2004) discovered that the site was not permitted to operate in terms of Section 20 and 21 of the Environmental Conservation Act, Act 73 of 1989. Despite the supposed ‘formalisation’ of the dump, the Mahwelereng community lodged a complaint about the negative effect of the site on health, the environment and the aesthetics of the area, and about the vandalism of existing infrastructure, such as the stadium that was situated on the site, and the way the site encouraged crime (Mashiteng, Citation2004:3). This led to an exploration of alternative uses of the site that would be more beneficial to the community.

4.2. Events that led to the creation of the MSNL

The idea of creating the MSNL originated in a study tour of the Limpopo Province conducted in 2003 by the Parliamentary Sport and Recreation Portfolio Committee and officials from the office of the provincial Member of the Executive Council (MEC). The group found the stadium in poor condition, mainly due to vandalism (Municipal Planner, 2015, personal communication), and not being used because of lack of water, and the policies in place at the time. The dumpsite next to the stadium, originally an abandoned quarry, was closed down in response to community pressure and rehabilitation of the site began, with the aim of turning the renovated stadium and former dumpsite into a facility for the residents of Mahwelereng. Interdepartmental meetings were held to discuss the community’s concerns and demands. Community representatives, through the IDP public participation process, confirmed that they wanted the site to be developed as a library and sport and recreation facility.

The matter of funding was addressed in the IDP review of 2010/11. The development was done through the local corridor development and township renewal programme, funded by the Municipal Infrastructure Grant (MIG) from the Treasury, which allocates funding for some of the IDP projects, and by the Neighbourhood Development Partnership Grant (NDPG), which allocates funding to improve the living conditions of the wider community of Mahwelereng and its rural hinterland (MLM, Citation2010:201). The cost of filling in the dumpsite and renovating the stadium was R42,328,000 (MLM, Citation2012:130,142).Footnote2 In 2011, following the grant allocation, Moholo Landscape Architects won the tender to develop the site.

Enthusiasm for developing the game of cricket, especially in black communities, led to a meeting of cricket organisers with the then manager of the Mogalakwena Local Municipality and the assistant coach of the Unlimited Titans Cricket Team. This resulted in the construction of a cricket pitch as part of the MSNL development, funded by the National Lottery, Cricket South Africa and the Northerns Cricket Union (MLM, Citation2011:216).

4.3. Current use of the MSNL

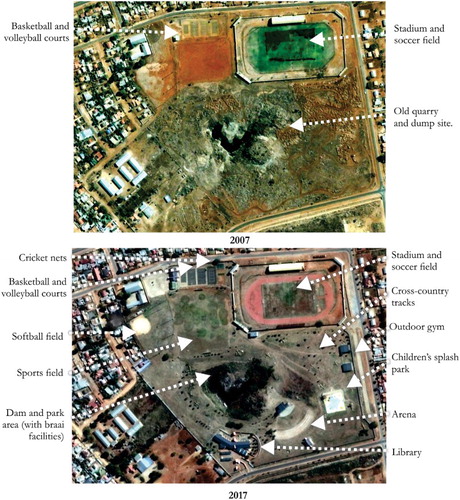

shows the site before and after development. The MSNL offers a wide variety of sporting, educational, cultural and recreational amenities, resulting in a mixed-use development where the various amenities support one another. The location and layout of the site were designed to create a public open-air area, where the youth could relax, where the aged could enjoy the natural feel and do some muscle stretching and where children could play under adult supervision (Municipal Planner, 2015, personal communication). The library was designed with open-plan internal spaces, the main library space being dominated by small tables, allowing for group interaction, and the walls and rear section of the library containing the books. The aim is to attract those who have not hitherto been acquainted with libraries and might be deterred by the traditional kind of library (LEMEG Architects, Citation2011). show some of these amenities.

5. Factors responsible for the success of the MSNL

This section discusses three aspects that interviewees and focus group participants identified as being instrumental in the success of the MSNL: the location; the lack of similar facilities in the wider region; and the fact that the amenities satisfy the needs and desires of the surrounding communities.

The MSNL is centrally located. It is within walking distance for many of its users, the bus route takes people straight to the door and people with cars who work in Mokopane drive there after work. Many respondents said they were happy with the facility’s close proximity and accessibility. The librarian mentioned the clear link between location, accessibility and capacity and said that the library is full in the afternoons, being used by pupils from surrounding schools and the neighbouring Further Education and Training (FET) college, as well as their teachers.

The maintenance team said that because the MSNL is the only intergenerational multipurpose interactive facility in the area, it attracts many people from Mokopane and neighbouring rural settlements. The maintenance control officer said the community of Mahwelereng ‘always come in their numbers to use the facility because it is one of a kind and cuts across all age groups’.

The landscape architect said the facility is what the community needed. He said that:

People come to the park in large numbers to enjoy the outdoors, to use the gym equipment, to play sports on the hard surface courts, the cricket pitch and the softball court, to jog on the cross-country track and to visit with each other. In particular, the gyms are extremely popular as everyone is fascinated by the idea of an outdoor gym.

It is much better coming to exercise here than at home because of the lack of space at home – plus doing it outdoors in the fresh breeze is really helpful. Coming from a very traditional background I have a strong belief in how much power nature has on the healing process, plus I love the fact that I have made friends who act as personal trainers when I need one.

Almost all the respondents praised the facility for providing a space for social interaction, sport and exercise – clearly this was something the community needed.

6. Benefits the community has gained from the MSNL

According to respondents, the MSNL has brought the community many benefits: increased safety and security; transformation of the character of the township; improved health; a space for learning and empowerment; and a strengthening of social capital.

6.1. Safety and security

Most of the MSNL’s users believed it had turned Mahwelereng into a safer place. A member of the aerobics group said the character of the township had been dramatically transformed by the provision of a space where community members were able to mix comfortably. According to this respondent, prior to the development of the facility the community was living in fear:

Walking in the street you would assess every creepy guy you passed on the street, or even worry about your kids walking home from school, as most people walking by would come from adjacent neighbourhoods and traverse the site to get to their different destinations.

6.2. Transformation of the character of the township

The stroke victim mentioned above described the township as a vibrant place full of people with good hearts. He said teenagers and adults still offer him help when he struggles with the gym equipment. The maintenance team voiced similar thoughts, saying that Mahwelereng is a very active community: they like to participate in anything that adds excitement to their lives. The team said ‘they like exposure and make use of any opportunity that will bring growth and empowerment into their lives’.

Many respondents wanted to share what they had experienced before and after the MSNL was created. A gym user, for example, said that when he first set foot in Mahwelereng, the township had lacked social stability and many ‘bad’ things happened, i.e. social ills arising from the neglected urban open space. He was of the opinion that since the opening of the MSNL many of these social ills had lessened. Similarly, one of the cricket facilitators said that since the opening of the MSNL he saw fewer children in the streets and more children spending time reading or playing sports. Another respondent said he was at peace knowing that every day after school his children were at the library reading or at the facility playing sports with other children.

6.3. Improvement of health

Adult and elderly respondents laid more emphasis on the issue of health. Some of the pensioners who live close to the facility visit it daily and others twice a month through the Mayoral Pensioners’ Programme, which organises transport for them to and from the facility. Some of the pensioners even said they have stopped using walking sticks since they started visiting the facility.

Some of the aerobics group visit the facility daily, in the mornings, afternoons or both, according to their needs. One of them said:

We visit the facility just to de-stress, unwind and share the mutual airing of our day which is good for one’s health. We safely share our struggles and joys or even ask about each other’s days, while also looking out for one another’s health and well-being.

6.4. Learning and empowerment

One of the librarians said that a library in a township like Mahwelereng keeps children informed because of the availability of reading material (novels, newspapers, magazines and textbooks) and technology (in the media centre) which exposes them to current developments worldwide. Another librarian shared this sentiment, saying that a library fosters mental development and self-development in the youth.

A teacher from the local school said that before there was a library in Mahwelereng pupils were not interested in reading, and as a result their performance was below average. Since the facility had been developed their performance had started to improve. She said it was the parents’ and the teachers’ responsibility to encourage pupils to use the facility. She said:

I visit the library often and read a lot. When giving my learners assignments and projects (ones that complement the curriculum of course), I order them to search for information on the given activities at the library as I know this is where they will find it and it will then be discussed in class. Kids and parents that love reading come here as the spaces at home do not accommodate that and most of these schools are not well equipped with these resources.

6.5. Strengthening of social capital

Many of the respondents considered that the combination of library and sports facility on the same premises helped to strengthen social ties. They thought it was a good initiative as it brings the community closer together, since the facility offers something for everyone. Many of them also met at the facility. One of the aerobics members commented that:

Through using it on a daily basis and minding your own business and seeing someone you have never met before being kind to you, you tend to develop the desire to get to know them, learn about one another’s backgrounds, develop mutual concerns and interests and goals, which is how this aerobics group started.

It was the same thing with the soccer and cricket teams, as they shared how they managed to break into the soccer league and the cricket development programme. Cricket, unlike soccer, has never been a popular sport in African communities, and as a result there are few black players in the national team. One cricketer said his love for cricket had developed when his cousins who attend former white schoolsFootnote3 in Mokopane would visit them in the township during school holidays and they would play cricket in the garden or streets with neighbours and friends. Thus, when the game was introduced later in the township and in their schools, he became keen to pursue it as a career. He said:

I know I need to work very hard on my fitness and skills and put in the hours for me to achieve my goal of seeing myself as a professional cricketer and I look up to Makhaya Ntini who succeeded against all odds despite coming from the deep rural areas of the Eastern Cape.

You do not have to go to private schools or come from the suburbs to succeed in life. Ever since the development of the facility there has been a great transformation in the township, showing that children from public schools or townships can amount to anything or even think beyond their means.

The facility was also said to strengthen social ties as it promotes teamwork, leadership and communication. This belief was expressed particularly by the groups (the cricket, soccer, aerobics and basketball teams). A member of one of these groups pointed out that the future of children in black townships is threatened by the lack of such facilities in their communities and at their schools. Many are discouraged because they feel that after completing matric they have reached the end of the road and they give up on life and settle for drugs. So they believe that the MSNL has brought a huge transformation to Mahwelereng.

Many of the students using the library believed that using the facility had strengthened their social ties with each other. It was observed that they formed discussion groups, although they were not necessarily friends or from the same school, to talk about problems with their schoolwork and to support and encourage one another.

This strengthening of social ties was also supported through the placement of a number of informal meeting spaces in the landscaped open space of the MSNL. These spaces were constructed through strategic placement of boulders and stone tables, as shown in and , and a number of them contained braaiFootnote4 facilities. These spaces provided areas for individuals and groups to relax and chat.

7. Challenges faced in running the MSNL

While the MSNL has mostly been a successful endeavour, as happens with any initiative there have been challenges in running the facility, most of these to do with maintenance and resources. Maintenance problems are of two kinds. First, the library staff said that when there are problems with the internet connection it can take the municipality up to a month to fix it. They said this was particularly a problem for FET students using the facility, as most of the resources they needed were electronic. Second, the landscape architect responsible for the site design said the landscaping contractor had, as part of the contract, been responsible for one year’s maintenance of the site. Since this contract had expired, the grounds had not been maintained and were now overgrown with weeds.

Two resource problems were mentioned. First, the library staff and the users, particularly the students who relied on the library for their academic sources, were frustrated by the limited quantity of books and other knowledge products. Second, the budget for electricity was inadequate. While the facility has lights, it apparently does not have a budget to pay for the electricity for those lights, with the electricity being supplied directly from Eskom (South Africa’s electricity utility). This means that lighting is used only when the facility is rented out, as a part of the rental cost can be used to pay for the lights. Other users, such as the sports teams, can use the facility only in the daytime.

8. Discussion and conclusion

We noted at the start of this paper that many municipalities do not sufficiently value parks, libraries and sport and recreation facilities. The success of the MSNL demonstrates why they should value them. The services offered by this facility provide not just recreation, which is important, but also a means to empower its users, especially the youth, and to develop social capital in low-income areas. The evidence we saw ranges from the health benefits received by the elderly who use the outside gym, to the learning resources provided to pupils and teachers by the library, to the motivation and self-discipline learnt by athletes using the sports facilities. Our findings are in line with the arguments made by Stilwell (Citation2006) and Mnkeni-Saurombe & Zimu (Citation2013) about community libraries, Whitley et al. (Citation2016) about the social development value of sports in low-income areas, and Thomson (Citation2002) about the value of parks.

In terms of how this case study can inform practice elsewhere in South Africa, and globally, this study demonstrates that integrating different types of public amenities, from sports facilities to libraries, to public recreation areas, into one facility can have a multitude of benefits. These include cost savings through the sharing of management, maintenance and construction, and convenience for users. The close proximity of the amenities means that users can shift from studying in the library, to resting in the park, to playing sport and so on, without leaving the facility. However, this case study also highlights the danger of not planning adequately for the operational phase of the project. The maintenance and resource problems mentioned above suggest that the MSNL may be facing a deterioration in the quality of services it offers.

Our MSNL case study also conceptually bridges a number of arguments made in the literature. For example, the question of whether public open spaces are valuable assets (Willemse & Donaldson Citation2012; Shackleton & Blair, Citation2013) or places of danger and crime (Mashalaba, Citation2013; Stats SA, Citation2015) is partly answered by the MSNL example. Open spaces that are un-landscaped and unsecured, like the site on which the MSNL was built, appear to be of little value. But a community park that has play equipment, braai areas, benches and so on, and, most importantly, security measures such as fences and security guards, is an asset valued by the community. In other words, public open space in South Africa cannot be assumed in every instance to be valuable to the community; it is only when it becomes a safe environment, with the relevant amenities, that it fulfils the functions traditionally associated with open space, as set out by Thompson (Citation2002).

The study also adds to the literature on libraries in South Africa by providing evidence of the importance of location. While some authors have briefly considered this (see Hart & Nassimbeni, Citation2014), our study provides qualitative evidence that by being strategically located within walking distance of primary, secondary and tertiary education facilities, a library can play an important role in supporting students’ development. It gives them educational resources, a space in which to study that is conducive to learning and the conditions for discussions with other students. By providing a service to multiple institutions, it has the added advantage of reducing the overall cost of providing library facilities. This supports the Department of Basic Education’s proposal that schools should have shared library facilities at a central public library (DBE, Citation2012).

In addition, this study has provided further evidence of the importance of the combined traditional and interventionist role that libraries play in low-income areas (Hart, Citation2006, Citation2010, Citation2012; Mnkeni-Saurombe & Zimu, Citation2013). The study found that both teachers and students relied on the library at the MSNL not only for obtaining learning resources (the traditional role) but also as a space to work in after school and where students could study together and provide both social and learning support, helping each other to learn (the interventionist role). This is particularly important for students living in low-income areas, as the home environment is often not conducive to doing homework (Bayat et al., Citation2014).

Finally, our study reinforces the argument that public meeting spaces in low-income areas are important for the development of social relations and social capital. As mentioned earlier, Massey (Citation2013) noted how the lack of public spaces in the newly upgraded housing area she was studying eroded social capital in the beneficiary community. Our study further reinforces this argument by demonstrating that when adequate public space is provided, social capital is strengthened. It also shows that a space with a variety of resources attracts a wider range of participants. From a social capital perspective, this implies that if an intervention is going to have a big impact in building social relations, it needs to offer a wide range of activities and amenities to appeal to the differing interests of community members.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the South African National Research Foundation and Department of Science and Technology for their financial support for Emma’s internship in 2015/16, through which the fieldwork for this paper was completed. We would also like to thank the numerous individuals who provided comment, peer-review and language editing for this paper. Any mistakes are solely the fault of the authors.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Stuart Paul Denoon-Stevens http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7640-0970

Notes

1 An IDP is a statutory strategic plan to guide South African municipalities’ capital and operational expenditure. It provides an analysis of the key issues facing the municipality and identifies the various programmes and projects that will be required over a five-year period to deal with these issues.

2 1 ZAR = 0.1277 USD using the exchange rate at close of business on 4 May 2012.

3 Given South Africa’s apartheid legacy, many citizens still perceive a difference between the schools that used to admit only white students and those that used to admit only black students.

4 A braai is the South African variant of a barbecue, with some cultural differences in the ritual of cooking and socializing.

References

- Bayat, A, Louw, W & Rena, R, 2014. The impact of socio-economic factors on the performance of selected high school learners in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Journal of Human Ecology 45(3), 183–96.

- Brangan, E, 2012. Physical activity, noncommunicable disease, and wellbeing in urban South Africa. PhD dissertation, University of Bath.

- COGTA (Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs), 2015. Presentation to the portfolio committee on sports and recreation, 4 August 2015. http://pmg.org.za/files/150804SRSA.ppt Accessed 27 July 2016.

- DAC (Department of Arts and Culture), 2015a. Annual report: 2014/2015. http://www.dac.gov.za/sites/default/files/ANNUAL-REPORT-2014-2015.pdf Accessed 26 May 2016.

- DAC (Department of Arts and Culture), 2015b. The state of libraries in South Africa. http://www.liasa-new.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/State-of-SA-libraries-2015.pdf Accessed 26 May 2016.

- DBE (Department of Basic Education), 2012. National guidelines for school library and information services. http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/NATIONAL%20GUIDELINES%20FOR%20SCHOOL%20LIBRARIES_small.pdf?ver=2015-01-30-081525-540 Accessed 27 May 2016.

- Denoon-Stevens, SP, 2007. Towards communities, beyond settlements: Failing to take account of practice in Delft South Community Hall. Honours dissertation, University of Cape Town.

- DPLG (Department of Provincial and Local Government). 2004. The municipal infrastructure grant programme: An introductory guide. http://mig.dplg.gov.za/Content/documents/Guidelines/Annex%20B%20-%20MIG%20Introductory%20Guideline.pdf Accessed 25 October 2016.

- Google Earth, Mahwelereng, Limpopo, 24° 8'40.91"S, 28°59'15.21"E, eye alt: 894 m, image dates 20/6/2007 and 22/6/2017, source: Digital Globe.

- Hart, G, 2006. The information literacy education readiness of public libraries in Mpumalanga province (South Africa). International Journal of Libraries and Information Services 56, 48–62.

- Hart, G, 2010. New vision, new goals, new markets? reflections on a South African case study of community library services. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science 76(2), 81–90.

- Hart, G, 2012. Moving beyond ‘outreach’: Reflections on two case studies of community library services in South Africa. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, Special launch issue, 42–55.

- Hart, G & Nassimbeni, M, 2014. South Africa’s LIS transformation charter: Policies, politics and professionals. http://library.ifla.org/834/1/200-hart-en.pdf Accessed 27 May 2016.

- Höglund, K & Sundberg, R, 2008. Reconciliation through sports? The case of South Africa. Third World Quarterly 29(4), 805–18. doi: 10.1080/01436590802052920

- Groff, E & McCord, ES, 2012. The role of neighborhood parks as crime generators. Security Journal 25(1), 1–24. doi: 10.1057/sj.2011.1

- Keim, M, 2003. Nation building at play: Sport as a tool for social integration in post-apartheid South Africa. Meyer & Meyer Verlag, Aachen.

- Kimpton, A, Corcoran, J & Wickes, R, 2017. Greenspace and crime: An analysis of greenspace types, neighboring composition, and the temporal dimensions of crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 54(3), 303–37. doi: 10.1177/0022427816666309

- Kruger, JS & Chawla, L, 2002. ‘We know something someone doesn’t know’: Children speak out on local conditions in Johannesburg. Environment and Urbanization 14(2), 85–96. doi: 10.1177/095624780201400207

- LEMEG Architects, 2011. Architects. http://www.lemeg.com/architects.html Accessed 31 July 2016.

- Mashalaba, YB, 2013. Public open space planning and development in previously neglected townships. PhD dissertation, University of the Free State.

- Mashiteng, MJ, 2004. An investigation into the rehabilitation and finding possible sustainable end land use of the Mahwelereng Landfill Site in the North Province. Master’s dissertation, University of the Free State.

- Massey, RT, 2013. Competing rationalities and informal settlement upgrading in Cape Town, South Africa: A recipe for failure. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 28(4), 605–13. doi: 10.1007/s10901-013-9346-5

- McConnachie, MM & Shackleton, CM, 2010. Public green space inequality in small towns in South Africa. Habitat International 34(2), 244–8. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.09.009

- MLM (Mogalakwena Local Municipality), 2010. Integrated development framework (IDP) Review, 2010/2011. http://www.mogalakwena.gov.za/docs/IDP/Mogalakwena%20IDP%20Final%202010%202011.pdf Accessed 25 May 2016.

- MLM (Mogalakwena Local Municipality), 2011. Integrated development framework (IDP) Review, 2011/2012. First draft. http://www.mogalakwena.gov.za/docs/IDP/2011_12%20Draft%20IDP.pdf Accessed 25 May 2016.

- MLM (Mogalakwena Local Municipality), 2012. Integrated development framework (IDP), 2012/2016. First draft. http://www.mogalakwena.gov.za/docs/IDP/FIRST%20DRAFT%202012-16%20IDP.pdf Accessed 25 May 2016.

- Mnkeni-Saurombe, N, 2009. Impact of the 2009 economic recession on public/community library services in South Africa: Perceptions of librarians from the metropolitan municipality of Tshwane. Mousaion 28(1), 89–105.

- Mnkeni-Saurombe, N & Zimu, N, 2013. Towards tackling inequalities in South Africa: The role of community libraries. Information Development 3(1), 40–52. doi: 10.1177/0266666913501681

- Nassimbeni, M & May, B, 2009. Place, space and time: Adult education, experiences of learners and librarians in South African public libraries. Libri 59, 23–30. doi: 10.1515/libr.2009.003

- Nassimbeni, M & Tandwa, N, 2008. Adult education in two public libraries in Cape Town: A case study. South African Journal of Libraries & Information Science 74(1), 83–92.

- Ngcobo, NR, 1998. The provision of recreation facilities for the youth in Umlazi township: A socio-spatial perspective. Master’s dissertation, University of Zululand.

- Pernegger, L & Godehart, S, 2007 . Townships in the South African geographic landscape: Physical and social legacies and challenges. Keynote address, Training for Township Renewal Initiative, South African Treasury, Pretoria. http://www.treasury.gov.za/divisions/bo/ndp/TTRI/TTRI%20Oct%202007/Day%201%20-%2029%20Oct%202007/1a%20Keynote%20Address%20Li%20Pernegger%20Paper.pdf Accessed 18 September 2015.

- Perry, EC, Moodley, V & Bob, U, 2008. Open spaces, nature and perceptions of safety in South Africa: A case study of reservoir hills, Durban. Alternation 15(1), 240–67.

- Pillay, S & Pahlad, R, 2014. A gendered analysis of community perceptions and attitudes towards green spaces in a Durban metropolitan residential area: implications for climate change mitigation. Agenda (durban, South Africa) 28(3), 168–78.

- Redpath, J, 2010. The correlates of victimisation in Galeshewe and implications for local crime prevention. http://www.khayelitshacommission.org.za/bundles/bundle-nine/category/243-5-research-documents.html?download=2354:55.%20Redpath%20on%20Galeshewe Accessed 18 September 2015.

- Ryynänen, M, 1999. The role of libraries in modern society. Keynote address presented at 7th Catalan Congress on Documentation, Barcelona, 5 November 1999.

- Shackleton, CM & Blair, A, 2013. Perceptions and use of public green space is influenced by its relative abundance in two small towns in South Africa. Landscape and Urban Planning 113, 104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.01.011

- Sibeko, SD, 2007. The provision and utilisation of recreation facilities for the youth at Ngwelezane Township, KwaZulu-Natal. Master’s dissertation, University of Zululand.

- Simelane, BD & CJCP (Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention), 2011. Community Safety Barometer: Phillipi. http://www.khayelitshacommission.org.za/images/members/secure/files-3a-and-3b/DOCS%20Barometer%20studies%202011/DOCS_Barometer%20study_Phillipi%20Precinct_FINAL_pdf%202011.pdf Accessed 25 October 2016.

- Stats SA (Statistics South Africa), 2015. Victims of Crime Survey 2014/15. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=1854&PPN=P0341 Accessed 18 September 2015.

- Stilwell, C, 2006. Boundless opportunities: towards an assessment of the usefulness of the concept of social exclusion for the South African public library situation. Innovation 32, 1–28. doi: 10.4314/innovation.v32i1.26510

- Swart, K, Bob, U, Knott, B & Salie, M, 2011. A sport and sociocultural legacy beyond 2010: A case study of the football foundation of South Africa. Development Southern Africa 28(3), 415–28. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2011.595997

- Thompson, CW, 2002. Urban open space in the 21st century. Landscape and Urban Planning 60(2), 59–72. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00059-2

- Whitley, MA, Hayden, LA & Gould, D, 2016. Growing up in the Kayamandi township: II. Sport as a setting for the development and transfer of desirable competencies. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 14(4), 305–22. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2015.1036095

- Willemse, L & Donaldson, R, 2012. Community neighbourhood park (CNP) use in Cape Town’s townships. Urban Forum 23(2), 221–31. doi: 10.1007/s12132-012-9151-3