ABSTRACT

Trust is assigning the right to act to others. Trust is therefore building community. But trust can increase and wane with complex consequences. Community was built differently in Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Tanzania reached independence already in 1961; Zimbabwe in 1980. Both were subjected to British colonialism. Both experienced liberation movements more harshly suppressed in Zimbabwe than in Tanzania. Both had large rural populations. It can be argued that some level of generalised trust among people within the state’s formal boundaries is a condition for a functioning democracy. Distrust that makes a citizen, a group or a whole category of people exit from the state’s basic institutions fragments the state. The question here is how government politics in rural affairs, both policy-making and the organisation of implementation, affected trust relations between rulers and rural citizens in the two countries. The assumption is the less positive meaning policy has, the less trust, a reduced willingness to assign authority to policy maker and implementers.

1. Questions of peasant-government trust relations in Tanzania and Zimbabwe

From a theory of the formation, spread and dissipation of trust, materials were collected in the two countries (up to about 1990) to test the trust theory through the interpretations of the data. How do variations on societal knowledge and experienced threats to basic life conditions affect trust in authorities? Three themes are investigated in this retrospective article: (1) How did the condition of rural poverty across the point of liberation, with large ambitions of rural improvement in the two countries, affect trust in government? (2) Looking back – how was rural trust in political authority affected by British rule and (3) How was trust there affected by liberation government rural policies and their implementation?

2. Risk, knowledge and trust

Trust is related to risk and knowledge. I assign trust to someone when there is an action I want to happen, but I cannot make it happen myself. I believe the trustee has the knowledge and the will to make the action happen. Risk is involved but I deem the risk level acceptable. Trust makes the action possible. I am away from home. I want my money taken to my home. The existing transport systems are flawed. I have a person I trust who is willing to take my money home. She can and might choose to run off with the money. I ask her all the same to do so. I trust her. The more connected I am to the person, the more the person shares my values, the more likely it is that she will deliver. The more secure positive knowledge I have of the person, the smaller is the risk, and the more reasonable is my trust. She can experience my trust as valuable. ‘Trust … involves a judgment, however tacit or habitual, to accept vulnerability to the potential ill will of others by granting them discretionary power over some good.’ (Warren, Citation1999:311). Or, as Charles Tilly says: ‘Trust consists of placing valued outcomes at risk to others’ malfeasance, mistakes, or failures.’ (Tilly, Citation2005:10). Trust can build community through different mechanisms: There is risk involved in trusting, but trust furthers action. Trust is thus socially constructive or productive. Trust expands a community without the trustor being sure that the expansion actually will materialise. Trust can backfire. Trust compensates for risk. Risk tends towards inaction, trust towards action in insecure situations. Trust makes crossing boundaries into threatening systems or communities possible. Trust is assigning power to the other and indirectly expanding your own power to act or to cause action. It is in this sense a plus sum game. Trust expands your community into the risk situation. Trust opens for movement, for insecure experimentation. Trust strengthens a social relation. Trust is an infrastructure for rational action, for reasoned action on obligations that otherwise might be left unattended. Trust – once established – is an increase in the power, the space for action, of the person trusted. The withdrawal of trust reduces that power. Trust potentially expands the social in the sense of two or more persons having a common intention.

Trust is in consequence a less important type of relation in integrated communities with specific, deep and shared member knowledge. System confidence reduces the need for trust. Seligman (Citation1997) argues that trust is especially important in modern, large, specialised and technically integrated societies. Persons may have a high level of technical knowledge but limited specific social knowledge. Trust is important for persons to move across institution boundaries and for person immersion in technical systems in complex and large societies. Trust will thus have increasing importance in changing, modernising societies. Trusting authorities in peasant societies may thus be one condition opening for modernisation.

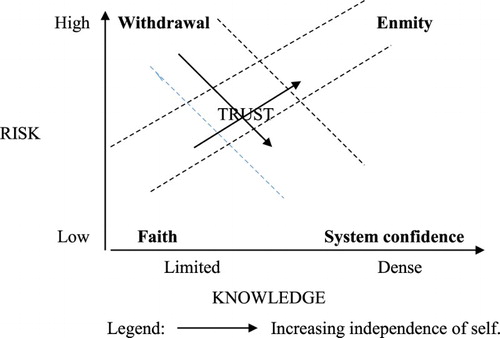

We can model the presence and transformation of trust along the two axes of risk and knowledge.

Comment to : (looked at from left upper corner): In a situation of fear and withdrawal, as system knowledge increases and risk is reduced, trusting others can increase. (From right lower corner): When social knowledge is deep and dense the need for trusting is reduced. (From left lower corner): In a situation of hardly any knowledge faith can create a feeling of integration, of belonging. As knowledge and risk increase, as for example when communities modernise (develop from communities to societies), trust becomes more important. (From upper right corner): But with deep knowledge of a split and therefore the image of a dangerous society, trust may be transcended into enmity.

In this way trust exists as an important activating social relation in the middle area of set between the variables of risk and knowledge. Trust is generated as people move away from the extremes in towards the centre area. Trust is dissipated as people’s conceptions move towards the extremes.

This is a meso-theory of the formation and dissipation of trust through contextual changes in relations between knowledge and risk. But how is trust in micro, between persons, between a trustor and a trustee, created in the trust space? Hardy et al. suggest: ‘Trust [is] a process of sense-making that rests on shared meaning and the involvement of all participants in a communication process.’ (Hardy et al., Citation1998:1). Trust is created through experience and speech-acting, when shared meanings are built (or discovered). To what degree did governments’ rural policy resonate with peasant conceptions of meaningful development? The less meaningful the policy, the less trust. How did governments balance a policy of industrialisation from above with a policy of rural development from below – perhaps towards more industrial production – the first generating mistrust, the second indicating shared meanings – and trust? How did these complex processes unfold in the two selected modernising countries, Tanzania and Zimbabwe in the mid–late twentieth century?

The study was part of the Admin Africa University project (The programme for university cooperation, NUFU) (Froestad, Askvik and Skarpeteig). The approach to data collection was to query the balance between private sector industrialisation and local community development of agriculture and industry in the public policy and the professional administrations of the two states. Five bureaucrats in the Department of research and specialist services in Harare were interviewed face to face. In the Ministry of agriculture in Dar es Salaam it was decided that some five section leaders would meet together to answer our questions. The results were corroborated in the Institute of Development Management (Chimanikire) and Department of Political Science (Chickwanha and Masunungure) in Harare; at the Institute of Development Management (IDM, Muzumbe, Milanzi) and in the Department of Political Science, University of Dar es Salaam (Kanwanyi and Shivji). Results were evaluated among colleagues at The Institute for Agrarian Studies, PLAAS, University of Western Cape (Hall and Cousins). Materials on peasant conceptions of governments and development were gathered also in Norwegian development-engaged institutions: town and regional development (Braathen and Eriksen); crop (St. Clair): Christian Michelsen’s Institute (Fjeldstad, Tostensen, Halvorsen), departments of geography (Fløysand and Aase), anthropology (Kapferer) and economics (Ahsan) at the University of Bergen.

3. Variations in causal processes: organised villages in Tanzania, settler economy in Zimbabwe

In the colonial period, peasants in Tanganyika were recruited or forced into seasonal work on plantations, transforming some of their villages into areas for subsistence to which underpaid workers on plantations returned out of season (Iliffe, Citation1979). Some peasants could improve their lot by becoming farmers on the outskirts of the plantations, exploiting markets created by the plantations. After liberation, the peasant subsistence economies in Tanzania continued but deteriorated under the centralisation and bureaucratisation of taxation regimes and marketing boards and under the increasingly forced villagisation programme (Collier, Citation1986). Many peasants-cum-workers migrated to the cities, only to be left there in unemployment or transported forcefully back to their villages. There were limited shared meanings between peasants and governments, despite the close Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) party administration of local communities through the ten-house system.

In Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe after liberation) the settler economy was a stronger regime of industry compared to Tanzania’s ‘softer’ plantation/agro-industry. The peasant economy in Southern Rhodesia was changed by the creation of ‘native reserves’ that undercut the autonomy of peasant subsistence production. Already in 1911, The British South Africa Company controlled 60% of the land, with European settlers in control of 20%. The last 20% were native reserves. The area under European control expanded up to 1930 to about 50%. After 1961, the white settler regime expanded the reserve area to some 45% of the land, then under the name of Tribal Trust Land (Moyo, Citation1995:81 and 117). The transformation of peasants to migrant workers took place in Southern Rhodesia, creating conditions of hunger in the reserve areas, despite sufficient food production (Shopo, Citation1985). The reserves were favourable to the development of shared meanings and political unity and power internally. That can be part of the explanation of the high presence of military state violence in Zimbabwe and the highly violent liberation process in the 1970s in Southern Rhodesia.

4. Government and peasant trust under British colonial rule

British colonial authority weighed heavily into the state building process in the two states under consideration. Tanganyika was invaded by a German military regime in the 1880s, which immediately met widespread opposition.Footnote1 After German defeat in the First World War, the League of Nations established Tanganyika as a protectorate under British rule. In Rhodesia, British authority was established in the 1880s through the British South Africa Company. In 1923, white settlers managed to resist incorporation into South Africa. Rhodesia became an independent state in the Commonwealth.

The British colonial governments were of an ad hoc and opportunistic character. They were not organised according to a centralised model or blueprint, like the west-African Francophile states. British colonial governments attended to problems as they arose and worked out viable solutions locally.

[British colonial] administration was essentially local in nature; colonial administrators frowned upon centralised controls from the Head Office, dispensed with extensive bureaucracy and paperwork, and were genuinely concerned, as far as the parameters of colonial domination reasonably permitted, not to disrupt the rhythm of indigenous communities. (Evans, Citation1997:10)

5. Liberation government characteristics

Having looked at the trust relations in the movement from colonial rule to liberation, how then did the liberated governments organise and how did they affect the integration of peasantry into a new society? Is neo-patrimonialism an apt concept for describing central traits of the new governments?

Two questions arise from the foregoing analysis (1) to what degree did the new governments manage to distance themselves from British colonial policy and traditions? And (2) to what degree were liberation governments independent of specific private/ethnic interests?

It was argued around 1980 that the African liberation governments were ‘balloons’ – large costly administrations without substance and power in society. They were called neo-patrimonial, i.e. elite ethnic based governments with large seemingly modern but substantially empty public bureaucracies, empty except for police and military power (Hyden, Citation1980; Jackson & Rosberg, Citation1982). A study of democratisation in 42 sub-Saharan states suggested patrimonialism as an apt description.

The institutional hallmark of politics in the ancien regimes of postcolonial Africa was neo-patrimonialism … Insofar as personalised exchanges, clientelism, and political corruption are common in all regimes, theorists have suggested that neo-patrimonialism is a master concept for comparative politics, at least in the developing world. (Bratton & Van de Walle, Citation1997:61–62).

The two governments had traits of neo-patrimonialism. Patrimonialism did perhaps not spring from traditional African authority structures, but from the colonial system of rule. When liberation movements simply contradicted colonialism, they claimed that the new state should serve the black Africans and them only. This is Mamdani’s (Citation1996) point that the liberation idea meshed with the socialist idea of a one-party state, a state for a specific class, not a state representative of all major classes and sections. The liberation idea was then that black Africans were one community, united through ages of white suppression and exploitation. They should have their own state. This idea opened for family-favoured recruitment to public positions. The idea meant scepticism to an emerging civil society. Civil society was an arena of organised power beyond direct government control, where different classes, movements, sections and organisations could act independently of rulers. Even privileged sections of the colonial society, it was argued, could thrive and act with power in the civil society arena. That idea produced an image of two antagonistic worlds – the colonists and their allies and the liberators, the common black Africans. That image made it difficult for liberation governments to develop a modernisation programme that incorporated the complex of social classes and modern institutions into a common multi-ethnic national reformist development strategy. Neo-patrimonialism conserved and drove distrust. The indirect-rule model was formally eliminated but was, in its direct contradiction, ingrained in the mindsets of the liberation movements (Chickwanha, Citation2006). Decentralised despotism under British rule was changed, about-turned, into centralised despotism in black liberation regimes (Mamdani, Citation1996).

If a general description of the liberation regimes should be suggested from these reflections, it would invite a weaker and more differentiated concept than the ‘master-idea’ of neo-patrimonialism. The government administrations in Tanzania and Zimbabwe were extensions of political loyalty and control. They were at best systems of trust among people familiar to each other (weak on generalised trust – Seligman, Citation1997). The governments around 1990 were political secretariats, with limited professionalism (Appiah et al., Citation2004). The administrative structures were seemingly modern, of the bureaucratic British generalist type, but weak. They were set in the ‘indirect rule’ paradigm. Policy implementation was dependent on the loyalty and willingness of traditional authority (chiefs). Government was distant to rural conditions and development.

6. Government competence in rural development: the problem

How did the colonial and liberated governments and subordinated agricultural administrations act as agents of agriculture and rural development? I will indicate some answers from studies of the national agricultural administrations in Tanzania and Zimbabwe (Gran, Citation1991, Citation1993).

The liberation governments had been dependent upon western donor- and financial institutions, more heavily so in Tanzania than in Zimbabwe. In Zimbabwe the strong industrialised settler economy made the country less dependent upon aid.

The assumption is that governments affect the space for trust and the development of shared meanings through policy and the behaviour of implementing agencies. It is people’s (clients) evaluation of the policy-making/implementation apparatus behaviour that determines the level of trust. Two research questions follow from the preceding narrative: (1) how did governments relate to peasants over time? What were central aspects of rural development policy? (2) how did governments organise the apparatus for implementation? Where did the agricultural bureaucracies have their loyalty? How did professionalism and effectiveness fare in those bureaucracies?

7. Tanzania: stable social democracy?

7.1 Regime politics: ujamaa failedFootnote2

In Tanzania in 1980, about 3.5 million households comprising 20 million people were small subsistence producers in agriculture. Many were bricoleurs, shifting between opportunities for life-sustaining activities as they appeared and learning through practice (Levi-Strauss, Citation1966). They had access to some 4.8 million hectares of land. Some 700 large plantations and farms, about 50/50 private and state owned, laid claim to about 2 million hectares. In economically peripheral areas large tracts of potentially useful land were available, some 12 million hectares (Havnevik & Skarstein, Citation1995). In Tanganyika, the black political elite, around TANU and president Nyerere, built an alliance with the peasantry in the 1950s through the expansion of the TANU party organisation into the countryside expanding trust in the movement and in government. The Indian trading bourgeoisie in the towns were ostracised from that political process, considered ‘class enemies’ (Rodney, Citation1980). From 1967 the turn towards socialism and the one-party-state, with the party formally superior to parliament from 1977, changed the state–society relation towards a type of command economy. TANU was transformed from mainly a mobilising movement to an instrument of government. The political mobilisation of the peasantry connected to the geographical expansion of TANU broke down. Shared meanings were broken apart. Modernisation depended increasingly on the use of hierarchy, of bureaucratic and military means. The Villagisation Programme moved some five million peasants into socialist ujamaa villages, with ambitions of modern large-scale production on collective farms. The regional co-operatives were dismantled in favour of national commodity boards. The conditions for peasant subsistence farming deteriorated partly because the concentration of peasants in and around the ujamaa villages led to environmental deterioration (Mapulo, Citation1973; Havnevik, Citation1993). The liberty of peasants to adjust their production to local needs, to environmental limitations and local/national market conditions broke downFootnote3. The basic condition for successful external (western) aid into rural development, namely the presence of independent land owning peasants with ability for innovation, was weakened. The result was that external aid did not reach the rural areas. It was increasingly absorbed into the bureaucracy. Bureaucracy as such expanded the balloon state. Some aid funds went to those relatively few commercial farmers with private connections into the bureaucracy. Those farmers, who could have become centres of rural technological and economic development, were isolated and ostracised politically. System confidence was reduced. Fear spread, favouring faith communities. Strength of governments increased.

7.2 Administrative normalisation: aid-supported bureaucratic balloons

In Tanzania the pool of high level black professionals at liberation was small. The scientific institutions were hardly present, except perhaps for a lively University of Dar es Salaam. Foreign aid helped to increase the number of academic, educational and counselling institutions. Sokoine became an independent University first in 1984. From 1965 the college was a Faculty within the University of Dar es Salaam. A number of management colleges and schools were created as institutes of practical counselling within sectors of the economy. Rugumamu’s study of knowledge transfer from abroad to agricultural research institutions argued that the value of such inputs of funds and personnel for Tanzania was dependent upon the strength and strategic consciousness of the Tanzanian recipient organisation (Rugumamu, Citation1992). He argued that the impact of the foreign assistance was negative, fragmenting and disorienting the Tanzanian organisations when recipient capacity was below a certain threshold. The Sokoine Agricultural University is an example of a Tanzanian institution above that threshold, making for a long time fruitful co-operation with Norwegian and other agricultural universities. Knowledge was generally on the increase.

In a comparative study of administrative competence in the ministries of education, industry and transport, the finding was that the large NORAD development projects in the 1980s weakened and fragmented the competence of the responsible Tanzanian institutions (Gran, Citation1993). One reason was that NORAD did not trust those institutions, making for separate, donor-controlled administration of development projects.

As an increasing number of Tanzanian PhDs were delivered at foreign universities, the chance of developing an esprit de corps and shared meanings in Tanzanian administrations was reduced. The Gran (Citation1993) study registered a rift in the ministries between the older politically recruited leaders, with loyalty to the TANU/CCM partyFootnote4 and younger, highly educated personnel that felt more at home in the professional mentality. The younger professionals had educational background from different centres of learning in the USA, Europe and Russia, connecting them into complex and important international networks. The professionalisation process was underway. However, the bureaucracy was, at the same time, under heavy influence from the older political cadres, with affinity to the socialist hierarchical mentality in TANU and with close ties to well-meaning donors.

In agriculture this politicised administrative structure can, according to Mukandala (Citation1992), partly explain the vacillation in policy and administrative organisation between centralisation and decentralisation, between democracy and bureaucracy, between independent co-operatives and powerful product- and marketing boards. Mukandala argued that the (younger) professional sections of the public administration in the 1980s were isolated, without access to policy making. The disbanding of the co-operatives was done against a counsel from sections of the (younger) government bureaucracy. Such insecurity affected the esprit de corps and shared meanings among professionals negatively, opening for neo-patrimonialism.

… bureaucrats in the regions and districts have taken advantage of decentralisation policies and built up ‘distribution coalitions’ with local elites, to the disadvantage of the peasantry. (Mukandala, Citation1992:71).

Verdal (Citation1998) investigated how the bureaucrats in the Ministry of Agriculture responded to the World Bank inspired Civil Service Reform programme, in which the Nordic countries had been substantial contributors. Her finding was that the central bureaucracy was generally passive, with limited resources to support development programmes in the field. The bureaucrats were sceptical to the Reform exercise, viewing it as a foreign input and basically, through the retrenchment programme, a threat to their own employment in the Ministry (interpretations supported in Munishi, Citation2006). The administrations became introvert, more interested in their own existence and welfare than in being agents of learning and development among peasants. Trust relations deteriorated.

The legitimacy, the common trust in the politicised leadership of the Ministry of Agriculture was reduced. A new professional culture was pushing its way into it, but the lack of public resources for agricultural development made for limited advances and a depressed work moral (Munishi, Citation2006). A politicised administration had more legitimacy when the ideology of ujamaa socialism made the hearts of some of the peasants beat more quickly, and when the international donor community supported what it considered an African variant of social democracy. Tanzania had an administration with bonds to international science. The lack of resources disconnected the administration from the local level and made government more prone to aid. Professionalism was underway, but still marginalised, with a negative effect on loyalty and engagement, producing a negative form of neo-patrimonialism at the local level.

The 1990s meant change in Tanzania. The co-operatives were revived. Private commercial farming and urban trade were no longer seen as immoral activities. Donors were increasingly showing trust in government institutions, at least in the sense that they were willing to finance reform efforts. The changes favoured detraction of power (spread of power to professionals Gran, Citation2005) and professionalism. However, the CCM political regime was still set in the ujamaa socialist paradigm, sceptical to devolution of power, multi-party democracy and professionalism within the ministries.

The public administration in Tanzania was under pressure to develop towards a modern, autonomous and professional bureaucracy, but the CCM culture was a heavy constricting burden. The multiparty system, which then was formally in place, was weak, in the sense that the opposition movements were elite formations without significant mobilisation among people. The donor organisations represented a parallel constriction in the sense that each major donor in practice financed and controlled its indigenous administrative offices with efficiency defined in the cultural/administrative context of the donor. This fragmented the Tanzanian administration and put Tanzanian bureaucrats under heavy conformist pressure. With Peter Evans (Citation1995), the possibility of embedded autonomy in the public administration–private entrepreneur relation in the country was limited. Fragmentation fed distrust.

8. Zimbabwe: a dictatorship?

8.1 Regime politics: the elite barrier

In Zimbabwe the Mugabe regime, which was ideologically similar to the socialist regime in Tanzania, came to power in a different society. The white settler community was in command of modern farming and agro-industry. Two nations resided within the country’s borders – the Ndebele and the Shona people. Mugabe led the liberation struggle to success in 1980 and unleashed both economic growth and improved democracy. However, the Mugabe Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) party (close to the Shona nation in Zimbabwe) had ambitions to eradicate Ndebele nation representation, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) party (and Ndebele identity), an ambition which led to civil war in the mid-1980s (Catholic Commission, Citation1997). In 1987 Zanu and Zapu were appeased, united in Zanu (Patriotic Front, PF), however not without ‘a legacy of health- and practical problems, material impoverishment and a mistrust of authorities’ (Catholic Commission, Citation1997:73). There were white and black political groups/parties in Parliament, making the Zanu PF creation of a one-party state more difficult than in Tanzania. The Mugabe government was from 1980 positive to land reform, transferring land from European to African ownership, making private ownership of land and some surplus production in small-scale farming possible. Between 1980 and 1998 some 3.5 million hectares were bought and transferred (UN Country Study, Citation2010).Footnote5 In the early 1980s, marginal agricultural land was distributed to subsistence peasants and migrant labourers coming out of the reserves. However, members of the black political and economic elite were increasingly favoured in acquiring also publicly purchased land from the commercial farmers. There was a contraction of power in the political elite disconnecting peasants from government.

The communal areas (earlier labour reserves) covered some 42% of Zimbabwe’s land area, with some 6 million people on that land of a total population in 1990 of 11 million. About 30% of the households were without land. Around 1980 many of those households with land were at the verge of food shortage, but a substantial number also managed to market some of their produce. Many of the poorest households had a female main person. Neither infrastructures nor knowledge of small-scale farming was sufficiently in place. The poverty nexus from the communal areas was reproduced on the small self-owned plots of land (Kambudzi, Citation1997). Rural poverty sustained faith. The lack of formal elementary education sustained strong family loyalty but scepticism to political authority. However, strong educational and research institutions in Zimbabwe sustained an increasing middle class, threatening but also driving political authoritarianism in the country.

Bricolage or the type of complex and shifting survival activities was normal among peasants in the communal areas. Poverty was rampant in peri-urban areas. Thus in class terms, the stagnation in rural agriculture in Zimbabwe was reproduced by the unholy alliance between the white settler community and a black commercially oriented elite. The Zanu (pf) political elite saw modernisation in traditional western terms: commercialisation of agriculture and urban industrialisation, absorbing surplus labour from the countryside. The working class and the peasantry, two separate but intermingled class formations, were seen as legitimate elements of civil society. Neither of these class formations however, seemed to be actively represented within the governing elite. Zimbabwe modernised in the early 1980s when liberation bolstered national independence. However, the country had traits of a counters society, divided between class formations that had little social interaction, beyond or above workers, peasants and serfs delivering surplus free of charge to the ruling class, in exchange – as it was said – for security. Trust was assigned to family, to people familiar for being members of the trustor’s own group. Zanu-Zapu violence generated fear and pushed trust towards withdrawal and enmity, and towards deeper faith and system confidence under socially peaceful conditions ().

8.2 Administrative normalisation: two cultures in conflict

The agricultural administration in Zimbabwe was centralised, with provincial offices as information-gathering and implementing outposts. It had a complex client structure. The white settler agro-economy was organised through the Commercial Farmers Union. The white settlers owned or controlled some 4400 farms on 11 million hectares of land. Black land workers were organised in the General Agricultural and Plantation Workers Union of Zimbabwe (GAPWUZ). There were some 320 000 such workers in Zimbabwe around 1980; 40% were of foreign descent, from Mozambique, Malawi and Zambia (Munyanyi, Citation1998). There were approximately 1 million black farming households, most of them in the communal areas, with access to common grazing land. In 1980 of 130 000 hectares of irrigated land, 3200 hectares or 2.5% of that land was in the communal and black community areas. Some 250 000 of the household farmers were in 1998 organised in the Zimbabwe Farmers Union (ZFU). Some 70 000 new farming households were created after independence through the resettlement programme. The Ministry of Agriculture was responsible for six agricultural colleges, which between 1980 and 1996 educated some 5800 extension workers, of them 1300 or 22% women (Mungate, Citation1997:7). Thus, civil society was thriving in Zimbabwe (Skålnes, Citation1995).

In the early 1980s many of the white bureaucrats in the Ministry left for employment elsewhere. Since 1980 the general policy in the Ministry was to serve black people in agriculture (implying the divided two-culture society). The Agricultural Policy Framework 1995–2020 made the creation and support of smallholder agriculture its first priority. The Framework confirmed that food insecurity was a problem for black households, despite the fact that total production in non-drought years was sufficient to feed the whole population securely. Some 20% of children attending school were malnourished or stunted in growth (Shopo, Citation1985). The Framework suggested that land redistribution be increasingly forwarded through village authorities, a policy confirmed by directors in the Ministry (in interviews). However, the main idea in the Framework was commercialisation of small-scale production. The bricoleur condition was not mentioned. ‘The first basic pillar in the government’s policy is the transformation of smallholder agriculture into a fully commercial farming system.’ (Framework, Citationn.d:1).

In our investigations in the 1990s we registered a Government–Ministry split. The government elite wanted the Ministry as a loyal political secretariat, while the Ministry, at least in addition, wanted to be heard as an independent professional. The agricultural competence of the Ministry in Harare seemed more established and stronger than in Dar es Salaam. The interviews disclosed scepticism in the Ministry towards the commercialisation programme. In the Department of Research and Specialist Services support to bricoleurs was favoured. Working with the traditional leaders was considered essential for successful assistance and development. The Department was engaged in the problems of food security in the villages. Networks to small-scalers were functioning, building government–farmer trust.

In Harare the high-level agricultural administration was professionalised, with productive connections to clients in the large-scale commercial sector. At the same time it worked towards farmers in the reserve/communal areas. The Ministry communicated with interest organisations for the different categories of landholders and producers in agriculture. These descriptions tally with conclusions drawn by Anne Thomson, cited in Harvey (Citation1988). She pointed to the administrative identification with clients:

The Ministry of Agriculture, which deals principally with producer prices, has certain advantages. It only has to deal with the farmer’s viewpoint, and it has a well-established mechanism for doing so, which dates from well before Independence. It is possible that the continuity of personnel has been greater in this Ministry … The marketing boards themselves appear to be reasonably efficient organisations … Farmers are usually paid within ten days, crops are collected efficiently, and costs appear to be reasonably under control … (Harvey, Citation1988:210–211)

The specialisation and autonomy of the public land administration in Zimbabwe seemed more developed than in Tanzania. The class divided Zimbabwean counters society, with the Shona–Ndebele struggle and with an ongoing political struggle between indigenous black and white communities, seemed however, to isolate the Ministry. Mugabe wanted a one-party state. The Ministry, with its relatively modern bureaucratic organisation was engaged in a policy of commercialisation. In this sense the Ministry was engaged in expanding the shared meaning between political authorities and upper class formations in agriculture in Zimbabwe. There was at the same time an under-stream of support for bricolage and small-scale agriculture.

Political processes have been turbulent and complex in Zimbabwe, affecting shifts in the development of trust relations. Strong economic development during the first five years of freedom favoured middle class democracy and generalised trust. Zimbabwe had a surplus of exports. Small scale producers were drawn into the economy. However, labourers on the large farms had serf-like conditions, favouring family bonding and fear of authority. The dictatorial turn of Mugabe in the mid-1980s affected the modernisation process negatively. Professionals left the country (Chickwanha, Citation2006). Trust relations dissipated towards enmity and withdrawal. With a real political opposition from the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC founded 1999) and its leader Morgan Tsvangirai, the modernisation process was gradually reinvigorated.

9. Conclusion: trusting relations in post-colonial societies: a product of welfare and democracy?

How then did the liberation governments in east/south Africa manage to expand the space for trust and shared meanings with peasants in the period 1960–2000? Was trust related to shared meanings and felt participation among peasants in policy making and its implementation? In effect, was trust related to the ebb and flow of democracy in the two countries?

From the investigated materials we discern powerful colonial penetration with exit from Tanzania 1961 and from Zimbabwe 1980. Indirect rule or rule through local persons of traditional authority was a characteristic of British rule, an idea that left some room for popular identification with authorities. To the degree that British colonialism had legitimacy among its subjects, it got that legitimacy from the exercise of local/national autonomy and thus an element of respect for peasants (the Mamdani, Citation1996 citizen/subject thesis).

Some neo-patrimonial traits, traditionalism within a façade of modern bureaucracy, were found in both liberation regimes. They did not serve a surge of trust relations. Peasants were not part of or weakly represented in the regime elites. The limited modernising capacity of the agricultural administrations among the small-scale peasantry did not boost trust. British indirect rule was changed to authoritarian direct rule, if not despotism in both countries (Mamdani, Citation1996). In Tanzania that change was fuelled by the massive western donor support to the state. Donor funding strengthened the elite and led to manifest infrastructural improvements. In Zimbabwe white professional competence left the country after 1985, certainly also pushed out by the ZANU/ZAPU organisations that had operated militantly over a long time for liberation. The Mugabe liberation regime deepened the ethnic Ndebele–Shona divide, perhaps leading to a defensive type of familiar trust building in each nation, but with dire consequences for a generalised national trust.

The agricultural programmes of both regimes were modernist: industrialisation and commercialisation of rural modes of agricultural production. Western modernisation culture was pushed into the regimes through multilaterals, western experts and NGOs engaged in aid. Both governments had meagre resources set on rural development relative to the extensive needs. There were weak structures of local government, less so in Tanzania. The state hardly reached the peasants with positive effects on their livelihoods. The Tanzanian state penetrated deeper into the rural areas, but with the ujamaa socialist policy failing to initiate autocentric (Senghaas, Citation1985)–self-driven rural development. The democratisation process was of the top-down type in both countries, seldom reaching substantially into indigenous communities. The condition for more trust was there, in the form of expanding modernisation and space for social movements, but not as more autonomy, more productive farming and more consciousness of individual rights among peasants.

Looking back at the materials on state formation, rural policy and agricultural administration in the 1980s reported on here, it is possible to discern a relation between power, shared meanings and trust. New states are products of power. Colonial penetration was such power, deepest in Southern Rhodesia, more superficially in Tanganyika. The anti-colonial struggle was violent from the very beginning in both countries, definitely more so in Zimbabwe. So the first task of liberation movements was to create shared meaning amongst its soldiers. Military power is also deontic power, the power of commitment to the political/military project. In Tanganyika, without an intransigent settler community, mobilisation for liberation was in the main a peaceful process on plantations, in government and school circles and in larger peasant villages. In Rhodesia it was a more conflict-prone project against settler class rule. This difference was manifest in the implementing agencies for rural development after liberation. In Tanzania the foreign owned plantations cooperated early on with the new TANU government. The agricultural administration supported the middle class peasants and managed infrastructures, avoiding serious famines (Havnevik, Citation1993). The state was far from democratic, but class relations were not steeply hierarchic. The space for trust was relatively large, system confidence was common in rural villages and trusting relations furthered modernisation in larger towns (like Morogoro). However, in Dar es Salaam, peri-urban slum-areas expanded, generating poverty, fear and enmity.

In Zimbabwe civil war and Mugabe-dictatorship broke down modern structures developed before 1980. System confidence within nations in Zimbabwe was low, as was trust in ongoing urban modernisation. The implementing agencies for agricultural policy had difficulty opening and expanding their competence beyond the large farms and agro-industry into peasant community developments. In this way there was little of the Tanzanian-type system confidence in rural communities in Zimbabwe. The divide between modern industrial/financial urban activity, with both white and black owners, and the huge rural areas of farms and townships packed with black and coloured workers made for more enmity and more faith than active trusting relations in Zimbabwe. How these relations changed from 1990, with MDC onto the scene in 1999, are questions beyond the materials investigated here.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The Maji-maji revolt was a tragic climax in the opposition struggle.

2 ujamaa, the Swahili for ‘familyhood’. was the social and economic policy developed by Julius Kambarage Nyerere, president of Tanzania from 1964 to 1985. Centred on collective agriculture, under a process called villagisation, ujamaa also called for nationalisation of banks and industry, and an increased level of self-reliance at both an individual and a national level.

3 A process that drew the peasantry into the modern socialist economy, a process that Gøran Hyden (Citation1980) underrated in his often repeated concept of the ‘uncaptured peasantry’ in east Africa. That criticism of Hyden appeared in Havnevik (Citation1993).

4 TANU shifted name to Chama Ca Mapinduzi (CCM, The revolutionary party) in 1977. CCM was a merger of TANU and the Afro-Shirazi Party on Zanzibar.

5 Later in 2000 a massive expropriation of white farms set in, redistributed in large parts to Zanu favourites.

References

- Appiah, F, Chimanikire, DP & Gran, T, 2004. Professionalism and good governance in Africa. Liber and Copenhagen Business School Press, Abstrakt.

- Bratton M & Van de Walle, N, 1997. Democratic experiments in Africa – Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Catholic Commission, 1997. Breaking the silence. Building true peace. A report on the disturbances in Matabeleland and the Midlands 1980 to 1988. The legal resources foundation, Harare.

- Chickwanha, AB, 2006. The politics of service delivery – A comparative study of administrative behaviour in Zimbabwe and South Africa. PhD., University of Bergen.

- Collier, P, 1986. Labour and poverty in rural Tanzania. Ujamaa and rural development in the united republic of Tanzania. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Evans, I, 1997. Bureaucracy and race. Native administration in South Africa. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Evans, P, 1995. Embedded autonomy – States and industrial transformation. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Framework. n.d. The agricultural policy framework 1995–2020. Government of Zimbabwe, Harare.

- Gran, T, 1991. The dilemma between mobilization and control in international aid the case of the Norwegian Sao hill sawmill project in Tanzania. Public Administration and Development 11(2), 135–48. doi: 10.1002/pad.4230110205

- Gran, T, 1993. Aid and entrepreneurship in Tanzania. The Norwegian development agency's contribution to entrepreneurial mobilization in the public sector in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam University Press, Dar es Salaam.

- Gran, T, 2005. The contraction- and detraction thesis. A theory on power and values conflicts in democracies. Chapter 18 in Larsen, U (Ed.), Theory and methods in political science. A first step to synthesize a discipline. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Hardy, C, Phillips, N & Lawrence, T, 1998. Distinguishing trust and power in interorganizational relations: forms and facades of trust. Chapter 2 in Lane, C & Bachman, R (Eds.), Trust within and between organizations. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Harvey, C, (Ed.). 1988. Agricultural pricing policy in Africa – Four country case studies. Macmillan Publishers, London and Basingstoke.

- Havnevik, KJ, 1993. Tanzania. The limits to development from above. Nordiska Afrikainstituttet, Uppsala. Almquist och Wicksell, Stockholm.

- Havnevik, K & Skarstein, R, 1995. Tradition, land-tenure, state-peasant relations and productivity in Tanzanian agriculture. Paper NFU. Norwegian Organization for Development Studies, Trondheim.

- Hyden, G, 1980. Beyond ujamaa in Tanzania: Underdevelopment and an uncaptured peasantry. University of California, Berkeley.

- Iliffe, J, 1979. A modern history of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Jackson, R & Rosberg, CG, 1982. Personal rule in black Africa. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Kambudzi, A, 1997. Land and water: Zimbabwès elusive democratic and governance measures. Paper presented at the Democratic Governance. Public Workshop, Harare, December.

- Levi-Strauss, C, 1966. The savage mind. Weidenfeld and Nicholson, Oxford.

- Mamdani, M, 1996. Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Mapulo, H, 1973. The social and economic organization of ujamaa villages. MA thesis., University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam.

- Masunungure, E, 1998. Presidential centralism and political input in Zimbabwe. Paper. Department of political science, University of Harare, Harare, September.

- Moyo, S, 1995. The land question in Zimbabwe. Southern Africa political economy series. Sapes Books, Harare.

- Mukandala, RS, 1992. The state and public enterprise. Chapter 5 in Oyugi, WO (Ed.), Politics and administration in East Africa. Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Nairobi.

- Mungate, D, 1997. Up-Grading of agricultural institutes and colleges in the ministry of lands and agriculture. Paper. ASMP/ASSP Senior Management Workshop, Harare, August.

- Munishi, G, 2006. Civil service reform in Tanzania. In Mukandala R, Yahya-Othman S, Mushi S & Ndumbaro L (Eds.), Justice, rights and worship- religion and politics in Tanzania. REDET. Department of Political Science and public Administration. University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam.

- Munyanyi, P, 1998. The social implication of the designation of commercial farms for resettlement on the farm worker. Paper. Seminar Zimbabwe Economics Society (ZES) and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES), Harare.

- Rodney, W, 1980. Class contradictions in Tanzania. In Othman, H (Ed.), The state in Tanzania. A selection of articles. Dar es Salaam University Press, Dar es Salaam.

- Rugumamu, S, 1992. Technical cooperation as an instrument of technology transfer: A case of agricultural research institutes in Tanzania. An interim Report. EATPS annual workshop in Harare, Zimbabwe, June.

- Seligman, A, 1997. The problem of trust. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Senghaas, D, 1985. The European experience. A historical critique of development theory. Berg Publishers, Oxford.

- Shopo, T, 1985. Rethinking parliament's role in Zimbabwean society. Working Paper No.3. Zimbabwe Institute of Development Studies.

- Skålnes, T, 1995. The politics of economic reform in Zimbabwe: Continuity and change in development. Macmillan Publishers, Basingstoke.

- Tilly, C, 2005. Trust and rule. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- UN Country Study, 2010. Harare. Zimbabwe.

- Verdal, H, 1998. Reform and legitimacy – Civil service reform in the Tanzanian ministry of agriculture. Masterthesis., Department of Administration and Organisation Theory. University of Bergen, May.

- Warren, M, 1999. Democratic theory and trust. Chapter 11 in Warren, M (Ed.), Democracy and trust. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.