ABSTRACT

The decade to 2015 saw rapid growth in trade between Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries. Much of this growth reflected South African exports to its neighbours of diversified manufactured goods to meet growing urban consumption and to supply inputs to mining and infrastructure. While most SADC countries, aside from South Africa, grew quite rapidly over this period, their exports remained oriented to a narrow range of minerals and agricultural commodities destined to go outside the region. Drawing from a series of sectoral studies, we assess key regional issues including the investment and production decisions of firms whose operations stretch across borders, and consider the implications for a bottom-up integration agenda that could build productive capabilities across countries. Our evaluation highlights the importance of the spread of supermarkets, the need to address transport and logistics, and value chains whose competitive advantages are inherently regional, as in the cases of poultry and mining.

1. Introduction

Most economies in the Southern Africa region, aside from South Africa, have grown quite rapidly over the past two decades. The generally high growth rates registered in the region have been accompanied by rapid growth in trade, notably exports from South Africa to the rest of the Southern African Development Community (SADC). This article provides an up-to-date examination of some key issues in regional growth and integration in Southern Africa.Footnote1

The approach taken is value chain oriented. This approach is consistent with an integration agenda that can be characterised as more ‘bottom-up’ in that classic regional integration objectives, such as efficient and tariff-free border passage, are considered within the optic of accomplishing specific objectives in key elements of value chains. This optic also facilitates the consideration of non-border measures such as regulations, partnerships and strengthening of regional institutions.

Four specific areas are in focus: the spread of regional supermarket chains, the poultry value chain, trucking, and mining equipment and related services. Separate articles on each area within this special issue provide greater detail on each area. These four areas were selected because they appeared to offer high potentials for growth and mutually beneficial trade and are critical to the nature and dimensions of regional integration.

A regional value chain approach also recognises the increasing organisation of production within and between firms across borders. While much attention has been on global value chains and their organisation (see, for example, Gereffi et al., Citation2005), countries competing in ‘tasks’ within these transnational production systems, there is also regional organisation of production which is linked to the observed growth in trade (see, for example, Keane, Citation2015; Farole, Citation2016). As highlighted in the studies drawn on here, international firms operate across Southern Africa and make linked investments at different levels of processing, trading in intermediate and final products to supply regional markets.

We also explore, as a cross-cutting theme, the issue of consistency between national industrial, agricultural and competition policies, on the one hand, and regional integration objectives, on the other, building upon Hartzenberg and Kalenga (Citation2015).

The remainder of this article structured as follows. Section 2 discusses recent trends in trade flows and in the regional integration agenda. Section 3 roots the discussion in literature relating to firm heterogeneity, vertical coordination of firms, and potential for market power. Section 4 considers the four specific areas mentioned above where a regional growth and development perspective may have particular promise. Section 5 discusses implications. A final section briefly concludes.

2. Trends

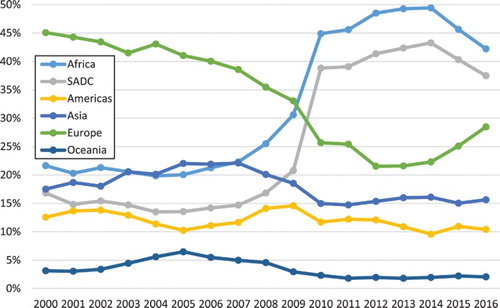

Regional trade, especially between South Africa and other SADC countries, has grown rapidly from the mid-2000s and has now reached levels that imply considerable macroeconomic significance. Africa, driven principally by SADC, has become the largest destination for diversified manufactured exports from South Africa, surpassing the European Union (EU) in 2010 ().Footnote2

Figure 1. Shares of South Africa’s diversified manufacturing exports (excluding basic metals, coke & petroleum and basic chemicals) by destination. Source: Calculated from Quantec data.

This growth in trade is consistent with the objectives of the SADC free trade area (FTA) and the successful implementation of the tariff phasedowns agreed upon within the framework of the FTA. The growth in trade in goods has been accompanied by rapid growth in trade in services alongside very significant foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa in general and SADC in particular (notably by South African firms) in sectors such as retail, banking, insurance, transport and business support services.

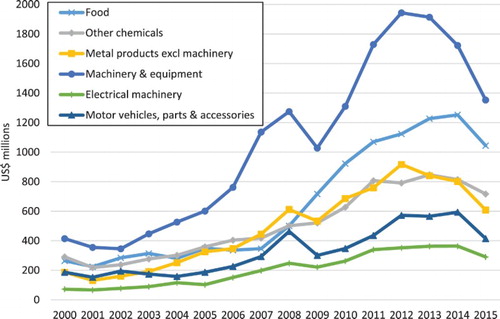

The growth in South African exports of manufactures to SADC countries has been led by food products and machinery & equipment (). The growth in food product trade is associated with higher incomes, urbanisation and the spread of supermarkets, while the largest source of demand for machinery & equipment stems from mineral extraction and processing. The decline in machinery & equipment exports from 2013 reflects the impact of the commodity price decline, which highlights the extent to which growth in regional economies leads to demand for South African exports.

Figure 2. South Africa’s leading exports to SADC countries (excluding basic metals, coke & petroleum and basic chemicals) (US$). Source: Quantec.

It is widely observed that South Africa has experienced greater success in exporting goods to the SADC region than other member states have had in exporting to South Africa. South Africa also dominates services exports and is by far the largest source of intra-SADC FDI. Bearing in mind that intra-SADC trade in goods and services, as well as FDI, was very small two decades ago, the rise of imbalanced trade and investment patterns is plausibly influencing the regional integration agenda. Whatever the exact causal factors, the regional integration agenda is changing in at least two important ways.

First, the momentum for broad-based policy steps to enhance regional integration has slowed considerably or even ceased entirely. For example, the establishment of an SADC customs union was initially targeted for 2010. This integration milestone is apparently more than delayed. Rather, it appears to have effectively disappeared, reflecting a greatly reduced appetite for implementation of across-the-board policy steps to enhance trade and regional integration.

Second (and related to the first point), there is frequent incoherence between national policies and the regional integration agenda. Notably, the collapse of progress towards a customs union has left in place wide differences in the external tariff rates imposed by SADC member states and a concomitant growth in the profile of rules of origin. In principle, rules of origin exist to prevent arbitrage of tariff protection rates across countries within an FTA. In practice, rules of origin can be employed to effectively block trade as opposed to merely preventing tariff rate arbitrage. In a broad review, Hartzenberg and Kalenga (Citation2015) conclude that most rules of origin in fact aim to protect domestic industries from regional competition. They also point to increasing application of other non-tariff barriers (NTBs) and ‘behind the border’ measures. Hence, at the same time as tariffs have been reduced, there appears to have been growing protection of national markets through NTBs (Hartzenberg & Kalenga, Citation2015).

3. Firms and regional trade

In a widely cited article, Melitz (Citation2003) expanded the focus of trade analysis from industries to firms. Building on the observation that productivities of firms differ widely within an industry, Melitz showed that, by expanding opportunities for relatively productive firms and exposing relatively unproductive firms to increased competition (in both product and factor markets), international trade could induce reallocations of resources within industries that generated aggregate industry productivity growth.

In South Africa, the recent availability of detailed data for the population of formal sector firms has allowed rigorous analysis of economic issues at the firm level, including trade. Kreuser and Newman (Citation2016), Edwards et al. (Citation2016) and Matthee et al. (Citation2016) confirm a very high degree of heterogeneity of productivities among manufacturing firms in South Africa. Kreuser and Newman (Citation2016) find that firm-level productivity is strongly associated with firm size, larger firms being more productive. Edwards et al. (Citation2016) and Matthee et al. (Citation2016) find that firms that engage in trade, meaning export of final goods, import of intermediate goods, or both, are generally more productive. Size, productivity and exporting are also associated in that firms that export a larger number of products to a greater variety of destinations tend also to be more productive (Matthee et al., Citation2016).

As noted, larger firms are also spanning the region in terms of FDI or other forms of long-term commitment such as service contracts for mining equipment. This spanning of the region by larger firms is consistent with trade favouring more productive firms, those firms tending strongly to be larger. It is also consistent with vertical coordination as a strategy for managing complex value chains that extend across borders. At the same time, the spectre of large, vertically oriented firms taking leading roles in regional trade patterns also generates concerns about competition and market power. These concerns are not idle ones. Fedderke et al. (Citation2016) use the same firm-level data sets to analyse markups as an indicator of market power and conclude that markups are relatively high in South Africa.

In any growth and regionalisation process, there will be winners and losers. In a healthy process, highly productive firms will have scope to grow and relatively unproductive firms will either increase productivity or shrink, at least in relative terms. For this process to drive broad-based growth, it is important that smaller but highly productive firms have genuine avenues for growth. This statement applies both to South Africa, where economic restructuring from the apartheid era remains a top-level concern, and the rest of SADC, where prospects for small firms to become large through linkages to regional opportunities are perhaps the major potential vehicle for benefit on the production side given the dearth of large firms outside natural resource extraction. This implies a strong accent on policies to reduce barriers to entry to facilitate the emergence of a healthy growth process.

To date, regional trade and investment flows have largely originated in South Africa. This is not surprising given the relatively high capabilities of South African firms combined with their relatively large size. In principle, a triangular pattern of trade – the region supplying the rest of the world and South Africa running a relative trade deficit with the rest of the world and a surplus with the region – is perfectly possible. In practice, this pattern of trade is already generating political strains. And, to the extent that these strains represent dissatisfaction with first-mover advantages and uncompetitive practices, these strains have an intellectually viable foundation.

The next section considers this constellation of issues in four key sectors. The objective is to highlight issues within areas of potentially significant mutual benefit. The policies necessary to achieve these benefits are in focus in section 5.

4. Regional trade and integration in key sectors

4.1. Supermarkets are shaping routes to market across the region

A supermarket revolution has been ongoing in Africa as part of the fourth wave of expansion identified by Reardon and Hopkins (Citation2006). In Southern Africa, it has been led by the two largest South African chains (Shoprite and Pick n Pay). Together, these two chains accounted for 366 stores across 16 African countries outside South Africa in 2016, all but three of which are SADC countries. South African companies have benefited from first-mover advantages in most countries in terms of establishing distribution centres and logistics infrastructure linked to the roll-out of stores (das Nair, Citation2018). Other chains have also been expanding in the region, including Shoprite, Walmart (through the acquisition of South Africa’s Massmart), Choppies of Botswana, and Spar (the Netherlands).

Alongside rapid urbanisation, supermarkets are changing food systems (Reardon et al., Citation2004). They are driving trade flows in food and consumer goods, as well as related services such as transport. While expanding into new countries, supermarkets have also broadened their client base from the traditional high-end affluent consumers in urban areas. They are successfully penetrating new markets in lower-income communities in both dense urban areas and towns supporting surrounding rural zones. The position of supermarket chains is due in part to heavy investment in regional distribution centres and logistics, which confers a high degree of control with respect to regional flows of goods. Second, on the demand side, the main supermarket groups maintain links with property developers to secure retail space in desirable locations on an exclusive basis. Local stores are left to occupy less desirable locations.

Supermarkets have therefore effectively become key governors of routes to regional markets, and hence of regional exports. However, there has been remarkably little research on just how the spread of supermarkets is affecting regional producers and trade flows. The effect is very significant. The majority of processed and packaged food products sold in supermarket chains in SADC countries (aside from South Africa) are not locally manufactured but are imported from South Africa or deep-sea suppliers. For example, it is estimated that more than 80% of the products sold in supermarkets in Zambia are imported, mostly from South Africa (das Nair et al., Citation2018).

Local food producers in countries such as Zambia and Zimbabwe are faced with greater import competition and must now meet the private standards and terms of the regional supermarket chains (Ziba & Phiri, Citation2017; Chigumira et al., Citation2017). To meet these requirements, local firms must invest in packaging, processing and systems to monitor quality and ensure traceability. These firms must also be able to supply large quantities. In essence, local firms must upgrade their industrial capabilities or face being excluded from the growing share of demand supplied via supermarkets. This is consistent with the literature discussed earlier, which finds that productivity growth from trade liberalisation is due to higher productivity firms expanding and exporting while low productivity firms go under (see, for example, Bernard et al., Citation2012). In the regional context, these firms are not evenly distributed but are mainly located in South Africa. There is a sharp implication that unless supermarkets are enlisted in concerted programmes to upgrade local supplier capabilities the unevenness of benefits will undermine regional integration.

The supply networks associated with supermarket chains do hold the potential to open up regional markets to local suppliers who can start exporting. If local suppliers upgrade their capabilities to meet the private standards and terms of the regional supermarket chains, then there is a much smaller step to regional export markets. In other words, the supermarket networks that have to date mainly facilitated the flow of foods and consumer goods from South Africa to the rest of SADC can also relatively easily facilitate multi-directional trade patterns.

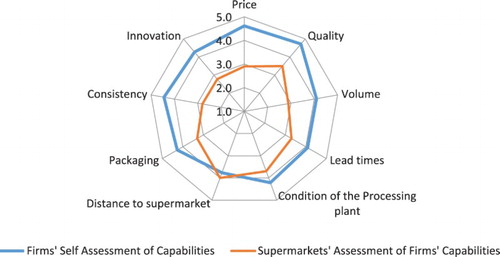

Three key barriers to realising the opportunities for suppliers were identified in the studies of Zambia and South Africa (das Nair etal., Citation2018; Ziba & Phiri, Citation2017). The first barrier is the gap between the supermarkets’ understanding of the suppliers’ capabilities and the perceptions of the suppliers. The results of a survey of supermarkets and suppliers in Zambia found Zambian suppliers rate their own capabilities much higher than the supermarkets do (Ziba & Phiri, Citation2017, ). These misalignments matter in terms of supplier development because they imply that buyers and suppliers do not have a common understanding of the capabilities gaps that need to be addressed and supermarkets are not sourcing locally because of their low rating of local suppliers.

Figure 3. Suppliers and Supermarkets Assessment of Suppliers Capabilities. Source: Ziba and Phiri (Citation2017).

The second barrier relates to the concentration of regional supermarket chains, with just three major chains dominating (das Nair et al., Citation2018). This concentration means the regional chains have power with regard to leasing commercial space on exclusive terms which undermines access to property malls for any rivals to the supermarket, such as butcheries, fruit & vegetable stores and local retailers. In turn, this reduces the routes to market for local suppliers. Practices of the major chains such as category management, which places the responsibility for organising shelf space in the hands of the main (regional) suppliers, also constitute a barrier to local producers (Ezrachi, Citation2010; das Nair et al., Citation2018). This can mean that, even where local suppliers are competitive, they are blocked or hampered from reaching consumers in the supermarkets because they are either unable to obtain shelf space or are relegated to the less desirable shelf space within the store.

Finally, there are market failures in supporting upgrading by local suppliers. Individual supermarket chains are likely to substantially under-invest in supplier development given that the benefit that the supplier accrues cannot be appropriated by that supermarket. For example, if Shoprite works with a Zambian soap supplier so that the supplier attains the capabilities to meet the full set of requirements to supply soap on a regular basis to Shoprite, that same soap supplier will have simultaneously acquired the capability to sell to any other supermarket chain, limiting the ability of Shoprite to earn a return on their investment. In the absence of appropriate interventions, the continued spread of supermarkets may undermine local production capabilities and further skew trade and production to South Africa, as well as deep-sea imports.

The policy responses thus far to address the implications of the spread of supermarkets for regional trade and integration have been piecemeal and reactive. For example, pressure has been placed on supermarket chains in Zambia since around 2012 to increase local procurement of dairy, processed grains, edible oil and household products. Commitments have been made and memoranda of understanding signed to work together with the Zambian Development Agency and private enterprise development programme (das Nair et al., Citation2018). However, it is not clear what monitoring mechanisms are in place and what sanctions can be applied for not meeting targets. Ideally, the efforts need to be part of a regional initiative but there have not been any signs of collective action at the regional level.

4.2. Regional food production: animal feed to poultry

Consumer demand for processed food has been increasingly strongly linked to urbanisation and rising urban incomes. If this demand is to be met by local production, there will need to be investment in expanded production from agriculture through to processing. The evolution of regional trade and productive capabilities in food is illustrated by developments in the poultry sector, one of the largest segments within agro-processing. Poultry is the most important source of protein in South Africa (Ncube, Citation2018), which reflects the relative efficiency of its feed conversion ratio of about 1.7 for poultry meat (broilers) compared with about 3.0 for pork and more than 10 for beef (Tolkamp et al., Citation2010).

Although poultry production has increased substantially on a regional basis, almost all countries in Southern Africa remain net importers (Ncube, Citation2018). South Africa, by far the largest market, experienced a trade deficit for poultry of US$274 million (or 22% of consumption) in 2015 and an oilcake trade deficit (used for feed) of US$153 million. Including the soybean trade deficit of US$49 million in 2015, the total trade deficit relating to the poultry industry in South Africa was US$476 million. Nearly all of these are deep-sea imports sourced from the likes of Brazil, the US and the EU.

To be internationally competitive, the poultry industry in Southern Africa must develop as a regional value chain, linking expanded production where there is the best agricultural potential for feed production, such as in Zambia, with investments along the chain. South Africa has competitive maize production, aside from drought years, but not soya (Esterhuizen, Citation2015). Maize and soya are the main components of competitive animal feed, which accounts for more than half of the total costs of poultry production. Competitive poultry production also requires capabilities in the logistics and advisory services necessary for efficient production in the region, in order to be competitive with imported poultry into South Africa (Ncube et al., Citation2017).

There are significant scale economies at different levels, including breeding operations, slaughtering and further processing for different consumer segments. A competitive industry thus requires coordination and linked investments in scale operations where the different components of the value chain are brought together. At the firm level, this is achieved through significant vertical integration and coordination, from feed production, downstream into broiler production, processing and distribution. These firms are integrators (Hendrickson & James, Citation2016). As noted, in Southern Africa the constraints of environment, particularly the water and land endowments, require this coordination and firm linkages to be across borders if the whole value chain is going to be competitive.

Commercial poultry in the region is largely undertaken by businesses that are associated with three main South-African-based groups, Rainbow (RCL Foods), Astral, and Country Bird Holdings (CBH). These groups operate across countries in the region, including through alliances and joint ventures with local businesses in different countries (Ncube, Roberts & Zengeni, Citation2016). They also hold rights to breeding stock, typically on an exclusive basis, from European and North American multinational corporations. Birds of just two breeding groups, Ross and Cobb, are predominant in the region. There are other important participants in countries with strong capabilities at one or more levels, such as National Milling Corporation in Zambia with capabilities in milling relating to animal feed; Zamchick, which is part of the Zambeef group, focused on meat production; and Irvine’s in Zimbabwe.

Intra-regional trade, production and competitiveness are all tied up with the decisions of a few regional producers, how they govern the value chain and whether policies facilitate or work against regional competitiveness. While vertical integration can support the large linked capital investments required at different levels of the value chain, the concentration means that there are concerns about market power and anti-competitive conduct. This has been evident in a number of competition cases in South Africa and Zambia involving poultry producers (Bagopi et al., Citation2016; Ncube, Citation2018). It also appears to be evident in the pricing of day-old chicks in Zambia. In 2012, day-old chick prices in Zambia were more than twice those in South Africa. Increased investment in production and competition in breeding stock brought a halving of chick prices in Zambia from 2012 to 2015 (Ncube et al., Citation2017).

Growth in Zambian feed production has indeed been rapid and Zambia moved to being a net exporter of feed in 2013/14, mainly to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Zimbabwe and Malawi (Samboko, Zulu-Mbatha, & Chapoto, Citation2018). The growth was in line with a ten-year plan from 2005 to 2015 which underpinned an almost tripling of production over the decade. In 2017 Zambia began exporting significant volumes to South Africa (Paremoer, Citation2018). By comparison, South Africa in 2016 produced only around half of the soya which it requires and prices are generally at import parity, undermining the competitiveness of animal feed, notwithstanding yellow maize (used for feed) prices generally being at export parity (Esterhuizen, Citation2015).

In terms of country policies, the record has been of countries narrowly protecting their own industries and undermining regional efficiencies. In particular, South Africa has not recognised the potential to support imports from the region. In effect, narrow South African interest groups such as soya farmers have undermined the potential for regional growth in a sector with the possibility for increased imports by South Africa from countries in the region to balance the growing South African exports of most products.

At the same time, the vertical integration and tendency towards concentration given scale economies, points to the need for regional regulation and competition enforcement. This could complement policies to support local companies in participating in different activities within the chain.

While the main challenges and the main companies are regional in scope, there is no coordinated regional policy to address obstacles to improved competitiveness and higher levels of growth. As mentioned, the regional dimensions of production and supply mean that transport and logistics are crucial to the efficiency of the poultry value chain, as with other regional value chains. We turn to transport issues in the next sub-section.

4.3. Intra-regional transport, regional value chains and cost competitiveness

Transport and logistics infrastructure is critical to reducing the costs of trade in goods and services and underlies deepening integration in value chains through the transport of intermediate inputs and production-related services. It is not simply about costs but about the overall efficiency and dependability of logistics which enable producers to integrate operations across borders in the region and overcome the colonial legacy of the fragmentation of economies. This legacy means that regional suppliers remain disadvantaged in competing to meet the demand of the main markets in Southern Africa, of which the biggest is the Gauteng Province in South Africa.

Road networks are the mode by which the majority of goods are transported in the Southern African region, and it is therefore critical to understand efficiencies, cost and price drivers, investments and market dynamics along road networks. Prices charged for overland cross-border freight in Southern Africa remain higher than in other regions of the world despite the input costs of road transportation (vehicles, fuel and drivers’ wages) apparently being lower than those in Europe and North America (Vilakazi, Citation2018).

Benchmarking indicates that transport costs from, for example, Zambia to Gauteng have been around twice what they should be. As a result, it is less costly to import products such as animal feed and refined sugar to South Africa from South America than to source both products from Zambia, even though Zambia enjoys a cost advantage in the production of each. With animal feed costs at around US$400/tonne in 2015 and transport costs at above US$100 from Zambia to Gauteng instead of at a competitive benchmark of US$40/tonne, transport costs effectively break the regional value chain and favour trade instead with deep-sea markets (Vilakazi & Paelo, Citation2017). Reducing transport costs by half would improve the competitiveness of regional producers of commodities such as animal feed by more than 10%, supporting stronger regional growth through integration.

The high costs observed are partly due to border delays and partly due to ‘behind the border’ issues (Hartzenberg & Kalenga, Citation2015). Border delays add around US$20/tonne to costs per day of delay for a bulk load and have a larger impact on sensitive goods such as perishable foods (Vilakazi Citation2018). Uncertainties about the time taken for intra-regional freight, however, potentially have an even greater impact than simply the direct cost. When the products being transported are intermediates in a value chain, the coordination of activities is fundamental. A delay at one level can mean production is stalled with potentially huge knock-on inefficiencies along the entire chain. As discussed in section 3.1, competitive supply of final goods to retailers (particularly formal supermarket chains) also requires on-time delivery, as lead times are an important non-price consideration.

In addition, there have been a number of competition concerns about road freight and trading (see also Ncube, Roberts, & Vilakazi, Citation2016). Regulatory restrictions can act as barriers to competitive rivalry and protect insider transport groups who can maintain higher prices. These restrictions include rules about who can collect and deliver cargoes in countries, as well as arrangements wherein firms have control over critical facilities such as storage. While such practices can support a local business grouping against bigger regional rivals, the costs are substantial if they undermine long-run export potential. Delays and obstacles can also be easily affected by standards and certification that are used by incumbents to block rivals rather than enforced as appropriate (Hartzenberg & Kalenga, Citation2015).

Improving intra-regional transport and logistics therefore requires joint action across a range of inter-related areas including border controls, standards, control over storage facilities and fostering increased competition and investment. In turn, this depends on appreciating the benefits of two-way trade and not viewing other countries simply as markets for South African producers. Rather than decrying the ongoing obstacles to regional transport and trade, it is critical to ask the question of who the winners and losers are, and how certain interests continue to shape the agenda. In this context, while exporting processed foods to the region, South Africa is overall a large net food importer and faces constraints of water and environment. These constraints are likely to be compounded by the implications of climate change. Barriers to regional trade may support South Africa’s farmers and provide protection for smaller local producers in other countries, but they undermine the benefits of agricultural growth across the region and competitive food value chains. In the wider Southern African region there is abundant water and potential for expanded food production which could be stimulated through improved transport and logistics.

The spread of supermarkets across the region provides opportunities for transport on backhaul trucking legs. The question is whether a more integrated region means growth in regional value chains to meet this demand and ultimately move the region as a whole into becoming a net exporter of processed food products.

4.4. Industrial capabilities and regional integration: machinery & equipment for mining

Machinery & equipment is the most important category of South Africa’s diversified manufactured exports to other SADC countries, and more than quadrupled in US dollar terms from 2003 to 2013 (). The machinery & equipment exports are largely of machinery for mining, minerals processing and related infrastructure investment, Zambia being the single most important market (Fessehaie, Citation2015). The backward linkages from mining to industrial capabilities in machinery & equipment are an important counter to the ‘Dutch disease’ effects which have more often been observed as undermining industrialisation in Africa (Sachs & Warner, Citation1997; Auty Citation2001; Fessehaie & Rustomjee, Citation2018).

The capabilities in mining machinery are underpinned by the fact that extraction techniques and related equipment are frequently location and situation specific, which promotes adaptation and customisation. This consideration was the principal driver behind the creation of the South African national system of innovation in mining machinery (Walker & Minnitt, Citation2006; Fessehaie, Rustomjee, & Kaziboni, Citation2016). Moreover, understanding the regional picture in this sector is important because of the potential for lateral migration of the relatively advanced capabilities to other industrial activities as well as the linkages with advanced services such in engineering and design (Lorentzen, Citation2008).

The industrial capabilities and export decisions are specific to firms and the clusters they build with suppliers. South Africa has developed as the hub for mining machinery and related services in Southern Africa, supported by a network of supporting institutions including public mining-related centres for research at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Mintek and several universities (Fessehaie et al., Citation2016). Over 2012 to 2014, South Africa accounted for 37% of Zambia’s total imports of capital equipment, which averaged R5.6 billion per annum. Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique and Zimbabwe follow in terms of the size of imports from South Africa, with more than R3 billion each, on average, per annum, reflecting shares in their imports of as high as 73% in the case of Botswana (Fessehaie & Rustomjee, Citation2018). The customisation, adaptation and design thus stretch across borders to meet the needs of mining operations in a range of countries. However, while the shares of imports coming from South Africa remain high, they have declined by around a third over a decade, a greater proportion of imports now coming from deep-sea sources.

At the same time, the ongoing decline in mining in South Africa, due essentially to resource exhaustion, means it is imperative to consider the wider regional market if the mining machinery capabilities base is to be sustained. For South African equipment manufacturers and service providers, exports account for a substantial share of output (equivalent to around 75% in 2012–14). Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) of mining capital equipment in South Africa have developed regional strategies and linkages (Fessehaie, Citation2015). Yet, the trade performance suggests that competitiveness against imports from outside the continent, and hence regional linkages, is weakening.

South Africa has developed a national system of innovation in mining capital equipment and engineering services. As such, it could provide the base for the development of a regional system of innovation to meet the growing needs across countries and provide the foundation for the growth of capabilities in capital equipment and mining-related services in the region. Such a system to address market failures and realise the benefits of collective action in terms of research, training and support for shared facilities for businesses requires a coherent regional policy framework. Unfortunately, the assessment of Fessehaie and Rustomjee (Citation2018) and Fessehaie et al. (Citation2016) is that national policies are not coherent when viewed collectively. Each country is looking to variations on local content rather than building regional capabilities with the attendant economies of scale and scope which can be realised from supplying the larger regional market. In addition, regional institutions linked to mining capabilities, including universities in neighbouring countries, have weakened over time rather than becoming stronger by making the most of the existing capabilities base in South Africa.

The OEMs’ regional strategies are not part of a coherent regional vision to capitalise on existing strengths while expanding opportunities across countries as part of a vibrant regional system of innovation (Fessehaie et al., Citation2016). Partnerships are needed to realise this regional potential. A regional system of innovation would solve problems through adaptation and customisation, involving skills and design. Regional institutions in research and training are critical for this to be achieved. Institutional collaborations between South African institutions and partners in other countries could rebuild capacity in research institutes and universities to address science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) disciplines. Such an agenda has apparently been stymied by narrow national interests.

5. Implications for regional integration

Southern Africa has huge potential for increasing agricultural production, especially in areas with good rainfall such as Zambia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Tanzania and Angola. However, the region remains a net food importer, South Africa in particular importing from deep-sea sources rather than from its neighbours. Mineral extraction will remain very important for many countries, driving urban incomes and generating demand for inputs, including specialised equipment.

As urbanisation continues apace, the consumer basket will continue to evolve towards more processed foods. The effect has been for South Africa to increase its exports to other SADC countries, including through the spread of supermarket chains. For there to be greater two-way trade, other countries have to develop productive capabilities in agro-processing. This is essentially a process of industrialisation via the manufacture of more sophisticated products, including packaging, quality control, branding and delivery.

We have argued that supermarkets are key partners. They are the route to market and are investing in distribution and logistics. To date, supermarkets’ domestic sourcing in the region has been limited and the supermarket sourcing patterns therefore have not supported two-way intra-regional trade and instead added to the political economy burdens that unbalanced trade poses for the execution of regional as opposed to national strategies. And the main supermarket chains operating in the region are South African. They are part of the explanation for growing regional trade flows combined with slow progress in developing integrated cross-border regional value chains. The obstacles for suppliers include meeting supermarkets’ standards and packaging, investing in productive capabilities, and cost competitiveness in sourcing and processing agricultural produce.

In addition, the relatively small number of large supermarket chains implies that they likely have market power in the short term; however, in the medium to long term, supermarket chains stand to benefit significantly from greater regional integration and sustained growth. Realising this positive medium- to long-term vision almost certainly implies a much more balanced flow of goods between countries. In order to ensure that suppliers located outside South Africa gain the capabilities to supply supermarket chains, and thus gain opportunities to penetrate broad regional markets, a regional policy framework is required to ensure that supermarkets support local suppliers to upgrade their capabilities and to blunt the market power that large supermarket chains are likely to have.

An important item on supermarket shelves is poultry. It represents a significant production opportunity for the Southern Africa region. The best evidence indicates that the region as a whole has the potential to compete globally in poultry, particularly in terms of import displacement. As noted, South Africa imports nearly US$500 million per year in poultry and related products. The single most important element in constructing a competitive poultry value chain is low feed cost. Here, there are positive developments, as investments in expanded feed production in Zambia in particular have led to exports of intermediate products in the form of animal feed and its components. Much more is required if production from countries such as Zambia are to make a dent in South Africa’s import requirements.

Two main constraints have been identified. The first one is high transport and logistics costs. These costs add to the price of the landed product in Gauteng and reduce the factory gate price in Zambia for exports to South Africa. A series of measures are required to reduce these costs. These include the regulatory environment for transportation between countries, competitive dynamics between providers of transport services, harmonisation of standards and more efficient borders. There are signs of improvements here, as return loads of South African exports to Zambia were reported at around R600/tonne (or US$45/tonne) in January 2017 as compared with US$110/tonne reported in 2014 (Vilakazi, Citation2018).Footnote3 However, it should be noted that road transportation costs for bulk products are relatively high even in the most efficient possible systems, and rail transport could reduce costs further.Footnote4

The second constraint is one that also limits supermarkets and transport: narrowly defined national policies that protect domestic interests in each country but do not support regional development in general and integrated regional value chains in particular.

Before proceeding to discuss mining and related services, it merits highlighting that a focus on supermarkets, trucking and transport,and the poultry value chain forms a coherent policy package with tangible benefits for all parties. A package that puts the focus on regional growth and breaks the current pattern of fashioning narrowly defined national policies will involve:

A regional policy of obliging supermarket chains to engage in local supplier development. The objectives should be broad focusing on observables such as total volume of sales or shares in total sales, number of local suppliers engaged, median sales of local suppliers to supermarkets and (eventually) export values. This approach allows flexibility for supermarket chains and suppliers in attaining objectives and maintains incentives for the supermarkets to engage with the set of suppliers with the best growth prospects. A regional policy for addressing market power and competition issues should also be devised.

A concerted regional policy to drastically reduce border costs, including transport delays, and to foment competition in trucking and related services throughout the region.

A recognition that the first two elements of the package enumerated above already represent significant steps towards a policy framework conducive to developing a globally competitive poultry industry in the region. Additional elements likely include:

Uniform external protection rates for poultry and feed, ideally across SADC, in a manner similar to the common external tariff of a customs union. The uniform external rate, applied uniquely to imports sourced from outside SADC, eliminates issues relating to rules of origin for these products. The level of protection for poultry should be set at the minimum level necessary to support investment in the industry and be scheduled to decline progressively to very low levels over (say) a ten-year period. The rate for feed and the main constituent products (that is, maize and soymeal) should ideally be very low or zero. Low cost feed is a necessary condition for a competitive poultry industry. If Southern Africa cannot compete in feed production at import parity prices, then prospects for a competitive poultry industry are poor and the economic logic for regional industrial policies directed at building a poultry value chain evaporates. This implies that support to farmers, including small-scale maize farmers, should be provided in forms other than protection. For example, it is critical to address the provision of inputs such as fertiliser. In addition, periodic droughts mean that imports of feed will be required at times, although with integration of regional markets and better use of water these could be from within the region.

Complementary production policies in countries with high potential (e.g. Zambia) that employ available land and water resources in a socially and environmentally sustainable manner. This is eminently possible; nevertheless, there are real questions relating to the role of smallholders and the need for accompanying investments such as irrigation and rural roads. Climate variability makes these investments even more important.

Finally, as noted, the poultry value chain requires a high level of coordination along the chain, which is normally accomplished via some degree of vertical integration. In the Southern Africa region, the animal feed to poultry industry is currently dominated by three South African integrated producers. A regional competition policy is, once again, required to ensure these producers do not abuse their position.

We now turn to mining and related equipment and services. Viewed from the perspective of the totality of regional mining capabilities and regional mining endowments, the logic for a regional approach is overpowering. Nevertheless, narrow national policies frequently prevail. For example, countries seek local content provisions, yet competitiveness in these sophisticated industrial products requires investment at economic scale for a regional market. Low commodity prices notwithstanding, solid potential for extractive industry growth exists throughout the region, except South Africa, where easily accessible resources have very likely been exhausted. While economically exploitable endowments of mineral resources in South Africa are in increasingly short supply, very substantial capabilities for efficient operation of mines, including the manufacture and servicing of specialised mining equipment, remain in South Africa. These capabilities will either be applied outside South Africa or they will wither away and the industrial base be lost to the region as a whole.

The initiatives we are referring to are quite different from the broad policy agendas being pursued at the SADC level and are more akin to the bottom-up agenda proposed by Hartzenberg and Kalenga (Citation2015). Deeper integration requires collaboration at the institutional level and initiatives to remove blockages to industry competitiveness across the region. The assessment of mining machinery points to the importance of universities and technical colleges, science and technology institutions and industrial policy bodies such as development finance and industrial development zones, working together with lead firms (generally multinationals) as well as local suppliers (Fessehaie et al., Citation2016). The upgrading of local suppliers requires the capability to improve technical capabilities as well as access finance and advisory services. Supermarket supplier development programmes are an example of concrete interventions to build productive capabilities across borders.

6. Conclusions

SADC has seen very substantial growth in regional trade flows since the year 2000, due in part to liberalisation and in part to growing incomes in the region alongside urbanisation trends. However, narrowly conceived national policies are undermining the development of regional industries. The role of collaborative research across countries is very important in building a common cross-country understanding to counter the tendency to pursue national agendas. This article and others in this volume contribute to such a regional picture, in identifying key considerations in important industries as well as cross-cutting issues in regional transport, the role of supermarkets and the application of industrial, agricultural and competition policies in SADC. Sustaining and deepening regional integration involves moving beyond the trade agenda to build strong institutional relationships to support productive capabilities across countries for competitive regional industries.

Acknowledgements

This article was produced as part of a research effort entitled ‘Growth and Development in the Southern Africa Region’ undertaken jointly with the World Institute for the Development Economics of the United Nations University and the Economic Policy Division of the National Treasury of South Africa.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Channing Arndt http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2472-6300

Notes

1 As noted in the acknowledgements, much of the research in this special issue emerged from a collaborative research project undertaken by the National Treasury of South Africa in partnership with the World Institute for Development Economics Research of the United Nations University (UNU-WIDER) among a host of other institutions. The project culminated in a conference entitled ‘Growth and Development Policy: New Data, New Approaches and New Evidence’ held in Pretoria in November 2016. A synthesis paper, written by Arndt, was made publicly available by UNU-WIDER (Citation2016) prior to the conference to facilitate discussion and critique. This article builds upon the synthesis paper, the discussions at the conference and subsequent comments and critiques of the synthesis paper as well as the component papers that comprise this special issue.

2 It should be noted that exports to countries in SACU were under-reported prior to 2010.

3 Interview with Heiko Koster, animal feed consultant, Pretoria, 12 January 2017.

4 Bulk transport will become less necessary if the region moves into higher-value products. For example, if Zambia exported birds rather than bird feed, the transport cost as a share of the value of production hauled would drop dramatically.

References

- Auty, RM, 2001. Resource abundance and economic development. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Bagopi, E, Chokwe, E, Halse, P, Hausiku, J, Kalapula, W, Humavindu, M & Roberts, S, 2016. Competition, agro-processing and regional development: the case of the poultry sector in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zambia. In Roberts, S (Ed.), Competition in Africa. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Bernard, AJ, Jensen, B, Redding, S & Schott, P, 2012. The empirics of firm heterogeneity and international trade. Annual Review of Economics 4, 283–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-110928

- Chigumira, G, Chipumho, E, Mudzonga, E & Chiunze, G, 2017. The expansion of regional supermarkets Chains, changing models of retailing and the implications for local supplier capabilities: a case of Zimbabwe. Forthcoming UNU-WIDER Working Paper.

- das Nair, R, 2018. The internationalisation of supermarkets and the nature of competitive rivalry in retailing in Southern Africa. Development Southern Africa, 29(4). doi:10.1080/0376835X.2017.1390440.

- das Nair, R, Chisoro, S, & Ziba, F, 2018. The implications for suppliers of the spread of supermarkets in southern Africa. Development Southern Africa. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2018.1452715.

- Edwards, L, Sanfilippo, M, & Sundaram, A, 2016. Importing and firm performance new evidence from South Africa. WIDER Working Paper, 2016/39. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Esterhuizen, D, 2015. The supply and demand for corn in South Africa. United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service, GAIN Report.

- Ezrachi, A, 2010. Unchallenged market power? The tale of supermarkets, private labels, and competition Law. World Competition 33(2), 257–274.

- Farole, T, 2016. Factory Southern Africa? SACU in Global Value Chains. summary report, World Bank, 2016.

- Fedderke, J, Obikili, N & Viegi, N, 2016. Markups and Concentration in South African manufacturing sectors: an analysis with administrative data. 2016/40. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Fessehaie, J, 2015. Regional industrialisation research project: case study on the mining capital equipment value chain in South Africa and Zambia. CCRED Working Paper, 2015/1. CCRED, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Fessehaie, J, & Rustomjee, Z, 2018. Resource-based industrialisation in Southern Africa: domestic policies, corporate strategies and regional dynamics. Development Southern Africa. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2018.1464901.

- Fessehaie, J, Rustomjee, Z, & Kaziboni, L, 2016. Mining-Related national systems of innovation In Southern Africa: national trajectories and regional integration. WIDER Working Paper 2016/84. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Gereffi, G, Humphrey, J & Sturgeon, T, 2005. The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy 12(1), 78–104. doi: 10.1080/09692290500049805

- Hartzenberg, T & Kalenga, P, 2015. National policies and regional integration in the South African development community. WIDER Working Paper 2015/056. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Hendrickson, M, & James, H, 2016. Power, fairness and constrained choice in agricultural markets: a synthesizing framework. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 29(6), 945–967. doi: 10.1007/s10806-016-9641-8

- Keane, J, 2015. Firms and value Chains in Southern Africa. ODI Working Paper.

- Kreuser, F, & Newman, C, 2016. Total factor productivity in South African manufacturing firms. WIDER Working Paper 2016/41. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Lorentzen, J, 2008. Knowledge intensification in resource-based economies. In Lorentzen, J (Ed.), Resource intensity, knowledge and development – insights from Africa and South America (pp. 1–48). HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Matthee, M, Rankin, N, Naughtin, T, & Bezuidenhout, C, 2016. The South African manufacturing exporter story. WIDER Working Paper 2016/038. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Melitz, M, 2003. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6), 1695–725. doi: 10.1111/1468-0262.00467

- Ncube, P, 2018. The Southern African poultry value chain: corporate strategies, investments and agro-industrial policies. Development Southern Africa, 28(4). doi:10.1080/0376835X.2018.1426446.

- Ncube, P, Roberts, S, & Vilakazi, T, 2016. Regulation and rivalry in transport and supply in the fertilizer industry in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. In Roberts, S (Ed.), Competition in Africa – Insights from key industries. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Ncube, P, Roberts, S & Zengeni, T, 2016. The development of the animal feed to poultry value chain across Botswana, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. WIDER Working Paper 2016/2. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Ncube, P, Roberts, S, Zengeni, T & Samboko, P, 2017. Identifying growth opportunities in the Southern African development community through regional value Chains: the case of the animal feed to poultry value Chain. WIDER Working Paper 2017/4. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Paremoer, T, 2018. Regional value chains: exploring linkages and opportunities in the agro-processing sector across five SADC countries. CCRED Working Paper, 2018/4. CCRED, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Reardon, T, & Hopkins, R, 2006. The supermarket revolution in developing countries: policies to address emerging tensions among supermarkets, suppliers, and traditional retailers. European Journal of Development Research 18(4), 522–545. doi: 10.1080/09578810601070613

- Reardon, T, Timmer, P, & Berdegue, J, 2004. The rapid rise of supermarkets in developing countries: induced organizational, institutional, and technological change in agrifood systems. e-Journal of Agricultural and Development Economics 1(2), 168–183.

- Sachs, J & Warner, A, 1997. Sources of slow growth in African economies. Journal of African Economies 6(3), 335–376. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jae.a020932

- Samboko, P, Zulu-Mbatha, O, & Chapoto, A, 2018. The development of competitive capabilities in Zambia’s poultry industry for the southern African market. Development Southern Africa.

- Tolkamp, B, Wall, E, Roehe, R, Newbold, J, & Zaralis, K, 2010. Review of nutrient efficiency in different breeds of farm livestock. Report to DEFRA (IF0183).

- UNU-WIDER, 2016. Growth and development policy: new data, new approaches, and new evidence – Part II: Southern Africa. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki. Link: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/growth-and-development-policy-part-2.pdf.

- Vilakazi, T, 2018. The causes of high intra-regional road freight rates for food and commodities in Southern Africa. Development Southern Africa. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2018.1456905.

- Vilakazi, T, & Paelo, A, 2017. Understanding intra-regional transport: competition in road transportation between Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. WIDER Working Paper 2017/46. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.

- Walker, MI, & Minnitt, RCA, 2006. Understanding the dynamics and competitiveness of the South African minerals inputs cluster. Resources Policy 31(1), 12–26. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2006.04.001

- Ziba, F, & Phiri, M, 2017. The expansion of regional supermarket Chains: implications for local suppliers: the case for Zambia. WIDER Working Paper 2017/58. UNU-WIDER, Helsinki.