ABSTRACT

Using the North-West University (NWU) as a case study, this article argues for and demonstrates the value of empirically assessing the impact of universities on their communities. A cross-sectional survey design (n = 984) was used to investigate the NWUs impact on three different communities, as well as to empirically assess the needs of these communities. Results suggest that community-based projects and services, work-integrated learning activities, and, to a lesser extent, the quantity and quality of a university's graduate students, as well as initiatives such as science and engineering weeks, open days, sports weeks, and botanical gardens likely represent the most powerful and viable avenues for universities to achieve impact in their communities, especially when such endeavours are specifically tailored to community needs. The findings also suggest that universities’ outputs do not necessarily equate with or guarantee impact, and that impact is optimised when outreach activities are based on the actual needs of communities.

1. Introduction

Despite its proclaimed importance, impact as a construct is not yet a consistent and clearly defined part of the discourse at South African universities, and, as such, it rarely appears to be measured empirically in this context. This situation is further compounded by the fact that what some universities report as impact would actually be better described as outputs, which do not necessarily constitute actual impact. This adversely affects attempts to understand, monitor, and enhance the impact of universities, and also thwarts efforts to obtain comparable data from different universities. As such, a need exists to empirically investigate and quantify whatever impact a given university might be having on communities with which it is engaged. Centrally important to these ends is that the prevailing needs in these communities be empirically assessed in order to ensure that community engagement initiatives are contextually appropriate, justified, and effective. In the absence of such an approach, conclusions about universities’ impact will remain speculative, and benchmarking will be rendered difficult, given the lack of comparable data. This issue is particularly salient in a country such as South Africa, which is faced with a multitude of social, economic, and other challenges, which universities can potentially play an important role in addressing as part of their community engagement initiatives. As such, a clear need exists for more research and for the establishment of clear research strategies to assess community needs and university impact. In an attempt to address this need, the main aim that was set for the study reported in this article was to argue for and demonstrate how an empirical strategy could be employed to assess community needs and the impact of a university on its communities by using the North-West University as a case study.

1.1. South African universities as agents of social and economic development and transformation

South Africa has 25 publically funded universities (Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2011). These institutions are present in all South African provinces, are generally well established and functional, and have valuable financial, structural, and human resources (Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2017). They are therefore ideally positioned to make an impact in their communities,Footnote1 and to contribute to South Africa's developmental needs and transformational agenda.

Most South African universities acknowledge and understand that part of their mandate, as stated in the White Paper 3 on Higher Education Transformation of 1997, is to contribute to social and economic transformation (Council on Higher Education, Citation1997). The details of how, what, and to whom this contribution should be were, however, not specified. An attempt to clarify this is evident in the White Paper for Post-School Education and Training (Council on Higher Education, Citation2014). However, according to Favish (Citation2015), this document still does not contain specific strategies to expand on this mandate (the ‘how’).

The initial call for transformation did, however, cause radical changes at South African universities (Centre for Higher Education Transformation, Citation2002; Badad, Citation2010; Council on Higher Education, Citation2016). Firstly, South African universities increasingly started to link their transformational role to several grand challenges (Stats-SA, Citation2013), such as: the eradication of extreme poverty and hunger; promoting universal primary education; gender equality and the empowerment of women; reducing child mortality; improving maternal health; combating HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; and ensuring environmental sustainability and the development of global partnerships (Stats-SA, Citation2013).

Secondly, South African universities started integrating their transformational role with their core business (i.e. research and innovation and teaching-learning) (Bender, Citation2008; Lazarus et al., Citation2008; Grobbelaar & De Wet, Citation2016). In the process, some universities developed a strong community focus, such as the Durban University of Technology (DUT, Citation2016) and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (Seshoka, Citation2015).

Thirdly, universities in South Africa started placing more emphasis on ‘community engagement’ (CE), not only to focus their transformational efforts but also to fast-track them (Bender, Citation2008; Department of Higher Education and Training, Citation2016). This caused a shift away from philanthropic approaches to CE to more knowledge/discipline-based approaches, causing CE to become more systematic and focused (Council on Higher Education, Citation2010; Kruss, Citation2012).

Finally, the call for transformation, as set out in the 1997 White Paper, triggered some South African universities to reimagine themselves (Thakrar, Citation2015) to perform a more prominent and active transformational role in the South African society. This is particularly evident in the University of KwaZulu-Natal's Transformation Charter (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Citation2017), in similar documents that were produced by universities like Stellenbosch (Stellenbosch University, Citation2013), and in the transformation and restructuring process that the North-West University (NWU) is currently undergoing (NWU, Citation2015b).

It is clear that all of the above actions have a potentially transformative value, because, for the first time, it makes South African universities more inclusive and accessible to a broader part of the South African society, which holds the promise of a variety of benefits to involved communities. These developments can perhaps lay the foundation for even better co-operation between South African universities and communities. For this to happen, South African universities will, first of all, have to determine what the state of their current impact and contributions on surrounding communities are, and how they might be best able to maintain or increase the relative degree of such impact. To do so requires feedback from communities and an assessment and understanding of community needs, as this will enable universities to direct their community-based initiatives in a manner that maximises their potential impact.

1.2. Measuring impact

The potential impact that universities could make is typically the result of a carefully planned and methodically executed process, which normally involve certain inputs, which over time may lead to various outputs. Judging by what is being reported by South African universities, inputs typically include staff, volunteers, time, funding, research, materials, equipment, technology, and partnerships. University outputs are usually taken to include workshops, services, products, curricula, resources, training, counselling, evaluation, and facilitation, to name a few (Lazarus et al., Citation2008; Cantor, Citation2012).

There also seems to be consensus that outputs cannot necessarily be equated with impact, and that the latter only occurs when actual change ensues (Canter, Citation2012). Most universities tend to predominantly view and report their impact in communities from an economic perspective (Parsons & Griffiths, Citation2003; Seifer et al., Citation2003; Ohme, Citation2004; Steinacker, Citation2005). However, some universities are also starting to report their impacts from a social perspective, and are able to show that their institutions provide important educational, cultural, social, and recreational opportunities and facilities to communities (Robinson et al., Citation2012; University of Birmingham, Citation2013). Nevertheless, conspicuously absent from the majority of these studies is an empirical assessment of these stated impacts.

Furthermore, despite its perceived importance, impact as a construct is not yet a significant part of the discourse at South African universities and, as such, it rarely, if ever, appears to be measured empirically in this context. Some universities refer to their ‘accomplishments’, while many others loosely refer to their ‘impacts’ or ‘outcomes’ in their annual reporting. However, based on the nature of their stated contributions, it appears that they actually refer to inputs and in some cases outputs, which do not necessarily constitute actual impact. They also tend to speculate about the changes that may have resulted from their CE activities and actions. However, in order for the impact of universities to be better understood, monitored, and enhanced, a need exists to empirically investigate and quantify whatever impact a given university might be having on communities with which it is engaged. As an intrinsic part of this aim, it is important that the needs in these communities are assessed in order to ensure that CE initiatives are contextually appropriate and effective. In the absence of such empirical investigation, conclusions about the impact that universities are having will remain speculative, and any benchmarking endeavours will be difficult, given the lack of comparable data. Given the fact that universities can potentially play an important developmental role, which can lead to transformation in a country such as South Africa, which is faced with a multitude of social, economic, and other challenges, a substantial need exists for more research and for the establishment of clear research strategies to assess community needs and university impact. This prompted the present study, which set as its main aim illustrating how an empirical strategy could be employed to assess community needs and the impact of a university on its communities by using the NWU as a case study.

2. Design and strategy

A quantitative, cross-sectional survey design (Johnson, Citation2001) was used in the present study. Accordingly, a structured questionnaire was administered to a randomised sample of 984 participants by a team of 14 trained fieldworkers in the study area outlined below.

3. Study area

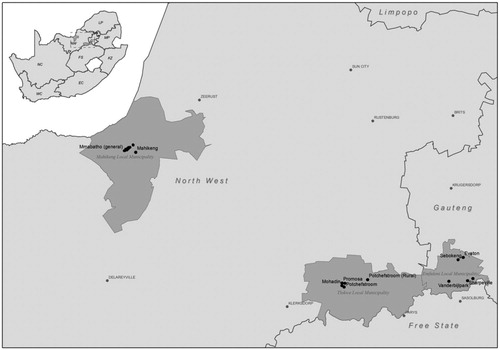

The current study was conducted in three different South Africa communities (municipal areas) – Tlokwe and Mahikeng in the North West Province, and Emfuleni in the Gauteng Province – as this is where the NWU's three campuses are situated (). It was argued that if the NWU was in fact impacting certain communities, the impact would likely be most notable in these three particular communities.

The Emfuleni community is the largest of the three communities that were included in the study. It is characterised by large-scale mining and industrial developments and reasonably well-developed infrastructure such as schools, medical services, police stations, post offices, etc. throughout the municipal area. Around 220 135 households are situated in the 45 wards into which this area has been divided (Emfuleni Local Municipality, Citation2014).3

The Mahikeng community is the second-largest community included in the study, with 31 wards and approximately 86 802 households. It is categorised as an intermediate-size city that is surrounded by 102 villages and suburbs (Mahikeng Local Municipality, Citation2017). Many of these villages can be classified as rural (even though some are situated fairly close to the city centre), in which many people still follow a fairly traditional way of life. Basic infrastructure and service facilities can be found throughout the municipal area, but are generally less available in some of the more remote villages.

Tlokwe (commonly known as Potchefstroom) consists of 49 212 households. As an intermediate-size city surrounded by agricultural areas, the Tlokwe community comprises 25 wards (Tlokwe Local Municipality, Citation2017). As is the case with Emfuleni, basic infrastructure and services can be found throughout the municipal area, and are available to most people in the community.

4. Method

4.1 Participants

Participants were selected based on a pre-calculated sample size that was proportional to each community's number of wards. In total, 984 respondents (445 Emfuleni residents, 307 Mahikeng residents, and 248 Tlokwe residents) took part in the study. A systematic sampling method was employed in the field, whereby every nth household (with n being determined according to the size of each community and ward) was selected to take part in the research. The mean age for the participant group was 41.18 (SD = 15.10), with ages ranging from 18 to 92 years. In terms of gender and racial composition, the sample was representative of both the regional and the larger South African population. The demographic characteristics of the participant group are set out in .

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants (n = 984).

4.2 Procedure and ethical considerations

The entire research process took six months to complete. Once the study was approved by the NWU's Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC), various community leaders in all three communities were identified, contacted, informed about all aspects of the study, and asked to provide their goodwill permission for the study. Once entry into the community had been negotiated, the sourcing and training of fieldworkers followed. A total of 14 fieldworkers were sourced from the three communities. A full day was spent on training these fieldworkers to successfully administer the survey in an ethically sound manner, using an approach that consisted of direct instruction, role playing, and individual monitoring and feedback. Once training was complete, fieldworkers were taken into the field, where each fieldworker administered between 7 and 11 questionnaires per day, based on the sampling method outlined previously. The fieldworkers were also transported to and from the various sampling locations to ensure that they followed the correct sampling frame. To be eligible for inclusion in the study, potential participants had to be permanent residents of the community in question, 18 years or older, and unrelated to the fieldworker. Care was taken to protect participants’ privacy and confidentiality, and this issue was addressed in detail during the training of fieldworkers, who all signed confidentiality agreements. At the end of each day, the completed questionnaires were collected and individually scrutinised for completeness and accuracy by a project manager. Once data collection was completed, questionnaires were sent to the NWU's statistical consultation services for data capturing.

4.3 Data gathering

Data were gathered by means of a structured questionnaire, which was translated into three languages commonly used in the communities in question, namely English, Afrikaans, and Setswana. Furthermore, most of the fieldworkers spoke all the languages prevalent in the regions in which they were deployed, and were also specifically trained to explain each question in the language and on a level that the participants understood. However, the majority of participants opted to complete the questionnaire in English, with only a comparatively small portion of participants in the Mahikeng region opting to complete the Setswana version.

The first section of the questionnaire gathered demographic information about participants’ age, gender, race, ethnic group, and employment status.

The second section of the questionnaire was comprised of two questionnaires. The first consisted of 12 items, measuring the impact of various aspects related to the NWU on a three-point ordinal scale ranging from ‘negative impact’ to ‘no impact’ to ‘a positive impact’, with an additional option indicating that respondents ‘do not know’. The second consisted of 13 items, assessing participants’ perceptions of the NWU's contributions to their communities, and these were measured in a five-point scale ranging from ‘do not agree at all’ to ‘fully agree’. These scales were developed by the researchers in consultation with the Director of the NWU's Institutional Community Engagement Office, based on the results of an institutional survey conducted amongst all NWU stakeholders (NWU, Citation2015a), as well as indicators used by other universities and the corporate sector in integrated reporting approaches to indicate their sustainability (NWU, Citation2015a).

The final section of the questionnaire was aimed at determining the perceived needs of residents in the three communities, and required participants to rate the extent of their needs in relation to 18 different items on a five-point ordinal scale ranging from ‘none’ to ‘very big’. Developed by the researchers, the questions related to community needs are based on research conducted by Coetzee & Du Toit (Citation2011a, Citation2011b).

4.4 Data analysis

Data were analysed by means of SPSS (version 22). Once the data set was screened for data entry errors and outliers, basic descriptive statistics were computed for all items in the questionnaire. Where relevant, relationships between variables were analysed by means of bivariate correlations, and between-group differences were assessed by using independent t-tests, ANOVA, and multi-dimensional chi-square tests following the procedure outlined in Field (Citation2009). In all instances, the cut-off value for statistical significance was set at p < .05, and the threshold for substantive significance of correlation coefficients was set at r ≥ .2. Cohen's d was used as measure of effect size when assessing differences in independent group means.

5. Results

5.1 The NWU's overall perceived impact and contribution

To assess the perceived impact that the NWU has on members of the communities surrounding its campuses, respondents were asked to indicate how much of an impact a variety of different outputs (listed in abbreviated form in ) associated with the NWU had on them or their households. Answers were recorded on a three-point ordinal scale ranging from a ‘negative impact’ to a ‘positive impact’, with another option allowing participants to indicate that they ‘do not know’.

Table 2. Perceived impact of NWU on local communities (n = 984)a.

As shown in , relatively few participants felt that any of the items listed exerted a significant negative impact on their lives. The most notable exceptions were the behaviour of contractors and service providers linked to the NWU, the professional advice that individuals either receive or fail to receive from NWU staff (e.g. consultation services, their serving on committees, etc.) and the professional/discipline-based support that respondents felt they received or failed to receive from NWU staff.

However, as is evident in , and confirmed by cross tabulation, the perceived negative impact of these factors was mostly experienced by Mahikeng residents. Specifically, 25.8% of Mahikeng residents felt that the behaviour of contractors had a negative impact, a moderately large (ɸ = 0.31) and statistically significant majority: χ2 (6, N = 976) = 90.82, p < .001. Likewise, 24.2% of Mahikeng participants considered the professional advice that they received or failed to receive from the NWU as constituting a negative impact: χ2 (6, N = 976) = 78.63, p < .001; ɸ = 0.28. An even larger difference (ɸ = 0.35) was noted in relation to the perceived negative impact of the professional support that 29% of Mahikeng residents received or failed to receive from the NWU: χ2 (6, N = 973) = 121.38, p < .001.

Several items listed in the questionnaire were rated as representing a significant positive impact. The most notable of these centred around the NWU's community projects, which, amongst others, centre on HIV/AIDS, technology development, library improvement projects, etc.; the NWU's community services (such as RAG, Yebo Angels, Musikane, Ikateleng, ECD training, Fazile Dube, etc.); the NWU's engineering weeks and open days, and the NWU's law clinics for the public (in the case of Tlokwe and Mahikeng) (North-West University, Citation2016). As confirmed by cross tabulation, the impact of the NWU's community projects and their community-based services were rated as more significant contributions in Tlokwe and Mahikeng than in Emfuleni: χ2 (6, N = 978) = 55.90, p < .001; ɸ = 0.24, and χ2 (6, N = 972) = 142.81, p < .001; ɸ = 0.38, respectively.

Cross tabulation was used to assess whether the perceived impact of the items listed in differed according to the race or gender of the participants. No gender differences were found; however, a statistically significant difference occurred in relation to the professional discipline-based advice that community members received from the NWU: χ2 (6, N = 948) = 28.60, p < .001. More specifically, 55.2% of white participants felt that this represented a positive impact, whereas only 35.3% of African participants did so. However, this difference was fairly small (ɸ = .17).

In addition to the assessment of impact, discussed earlier, respondents were also asked to indicate their level of agreement with several statements (listed in abbreviated format in ) related to the contribution made by the NWU to the respondents’ respective communities. Responses were recorded on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (don't agree at all) to 5 (fully agree). contains a summary of the results.

Table 3. Perceived contributions of the NWU to the communities surrounding its campuses.

As is evident in , mean scores were somewhat above average in relation to virtually all items, with the exception of the impact attributed to the NWU's associated subsidiary, for-profit, and not-for-profit companies, which was regarded as neutral. This suggests that, with the exception of the latter, the NWU is regarded as making a moderately positive contribution to its surrounding communities via all the aspects noted in . In particular, the NWU's service learning or work-integrated learning activities (e.g. students working as teachers, social workers, nurses, and other professionals as part of their training), were perceived as its most significant overall contributions to its surrounding communities. This was especially so in relation to the Tlokwe and Mahikeng communities, and significantly less so in the Emfuleni community, as confirmed by a one-way between-subjects ANOVA: (F(2,973) = 29.34, p < .001, partial η2 = .06).

The next most significant contributions of the NWU were its involvement in support programmes (e.g. for science and maths teachers/schools), followed by the NWU's science weeks and open days. The former contribution was perceived as more significant in Tlokwe and Mahikeng than Emfuleni, as shown by a one-way between-subjects ANOVA: (F (2,968) = 20.34, p < .001, partial η2 = .04).

Also noted as a substantive contribution of the NWU were the number and quality of graduate and postgraduate students delivered by the NWU, as well as the cultural activities associated with the NWU (e.g. shows, festivals, art exhibitions, choirs, etc.), especially among residents from Mahikeng and Tlokwe (but not Emfuleni), as confirmed by one-way between-subjects ANOVAs: F(2,976) = 38.39, p < .001, partial η2 = .07; F(2,972) = 30.58, p < .001, partial η2 = .06; and F(2,973) = 26.89, p < .001, partial η2 = .05, respectively. Further regarded as a significant community-level contribution of the NWU (especially on the Potch campus) was the NWU's sports weeks and training clinics.

To better understand for whom these community contributions were the most significant, responses were also disaggregated and comparatively analysed by means of independent t-tests according to gender and racial groups (which were restricted to African and white participants due to the small sample of participants of colour). In relation to gender, only one minor statistically significant difference emerged, in that males were more likely than females to regard the NWU's science centre and botanical garden as a positive contribution (mean difference = 0.17; d = 0.15) (t = 2.36, df = 953, p = .02, one-tailed). Racial differences in perceived contributions were far more prevalent, with the largest differences being that white participants were more likely than their African counterparts to view the following as significant contributions of the NWU: the NWU's indirect economic impact in their communities (e.g. as employer and supporter of local suppliers, etc.) (mean difference = 0.94; d = 0.96) (t = 7.94, df = 927, p = .000, one-tailed); the relevancy of both contract and academic research conducted by the NWU (mean difference = 0.67; d = 0.75) (t = 6.17, df = 931, p = .000, one-tailed); and the NWU's science centre and botanical garden (mean difference = 0.66; d = 0.66) (t = 5.51, df = 927, p = .000, one-tailed).

The associations between the contributions listed in and participants’ ages and income levels were assessed by means of Pearson's correlation coefficients. Whereas participants’ ages were not related to their perceptions of the NWU's contributions, their income levels were positively associated with the NWU's indirect economic impact in communities (e.g. as a significant employer in the region and a supporter of local suppliers, etc.) (r = .29, p < .001), and the relevancy of academic and contract-based research conducted by the NWU staff (r = .27, p < .001).

5.3 Perceived needs in communities where NWU campuses are based

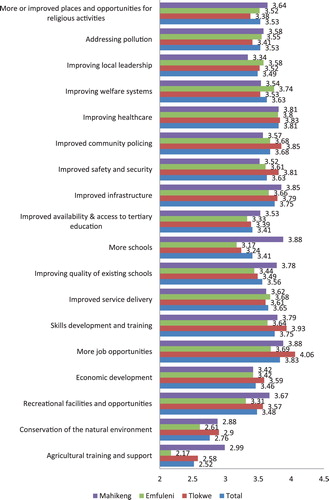

To assess whether the NWUs CE initiatives line up with community needs, respondents were asked to rate the needs in their communities (as reflected in ) on a five-point scale ranging from none (1) to very big (5).

As reflected in , the most significant needs of respondents revolved around a desire for increased job opportunities, more and better-quality healthcare (e.g. clinics), skills development and training, and more and/or improved infrastructure in their communities. Other needs experienced as important included those for improved community safety, security, and policing (especially in Tlokwe), as well as for improvements to welfare services and service delivery. The need for improvement of the quality of existing schools was experienced as fairly substantial among most residents, but particularly so among those residing in Mahikeng, where pronounced need was also expressed for more schools to be built. Members of all communities, especially in Mahikeng, also desired improvements in relation to places and opportunities for religious activities.

In contrast, the least pressing needs were for agricultural and farming training and support for local people (which was particularly low in the Emfuleni region), and also for conservation of the natural environment around the community. Whilst these findings are understandable in the case of Emfuleni, which is a predominantly industrial region, they are significantly less so in the case of Tlokwe and Mahikeng, where significant agricultural activities occur. Additional research would be required to ascertain why these needs were perceived to be relatively low in these communities. However, a plausible explanation might be that, as the surveys were mostly conducted in urban, residential areas, participants from rural regions who might have responded differently to these items were likely underrepresented in the sample.

6. Discussion

This study set out to argue for the need to empirically assess the impact that universities have in their surrounding communities, as well as for the importance of assessing the prevailing needs in these communities, and to demonstrate such an approach using the NWU as a case study. Overall, the results of the study, which was based on a cross-sectional survey design, revealed that the NWU's most substantive impact ensued from its community-based projects and services. Two such projects in the Tlokwe community include Mosaic and Ikateleng, and a large programme containing more than 70 different student outreach projects (North-West University, Citation2016). Mosaic focuses on housing, education, and employment; Ikateleng provides supplementary tuition in school subjects such as mathematics, English, science, accounting, and economics at a number of schools in the Tlokwe community; while the majority of the student projects focus on early-childhood development. All these projects therefore address genuine community needs related to education, employment, and infrastructure that were identified in this study, which underscores the importance of aligning CE initiatives with actual community needs; a sentiment also echoed by Erickson (Citation2010). In the Mahikeng community (an area that is more arid than the areas in which the NWU's other two campuses are based), projects such as Madibogo provide drinking water to communities, veterinary services to farmers who keep livestock in communal grazing areas, and free legal aid, whilst also focusing on improving early childhood development at local pre-schools (North-West University, Citation2016). Given that factors such as quality of schooling and infrastructure were identified as community needs, it seems plausible that these projects have a notable impact due to the fact that they address local community needs in a contextually sensitive manner.

Being situated in a more industrialised part of the country, the Vaal-Triangle Campus focuses on working with the industrial and corporate sector, and does so by offering various types of training (such as its ArcelorMittal, Coachlab, enterprising women, and accounting studies projects, see North-West University, Citation2016), which also seem to be in line with the needs of this community. Taken together, these findings imply that expansion and/or duplication of these projects and services might represent a fruitful avenue for further enhancing the NWU's impact in its respective communities. On a broader scale, these findings suggest that South African universities could indeed exert a substantive impact in their surrounding communities via their community-based projects and services, and that this might likely be one of the most viable and significant avenues for achieving impact with CE activities; especially if these activities are discipline (knowledge) based (Bhayat & Mahrous, Citation2012; CAISE, Citation2016). At the very least, these findings suggest that these types of initiatives might represent a fruitful focus for future research on university impact.

A second perceived positive impact are the NWU's service learning and/or work-integrated learning activities, such as students working as teachers, social workers, nurses, or other professionals as part of their training, which appear to directly speak to the most pressing needs identified in the three communities. This could perhaps be expanded to other disciplines, which can use their own expertise to make a difference in communities whilst simultaneously achieving institutional aims related to teaching and learning. Service learning and/or work-integrated learning activities represent an ideal avenue for addressing specific community needs. The findings of the present study underscore this, as the needs for more and better-quality education, health care, social work, etc., which were identified in the three communities, appear to be directly addressed by the NWU's service learning and work-integrated activities. The broader implication of these findings, as also concluded by Erickson (Citation2010), is that service and work-integrated learning activities likely represent one of the most synergistic, effective, and viable pathways through which universities could achieve substantive impact in their communities whilst simultaneously advancing their own institutional aims. At present, the majority of South African universities have service learning projects. Some universities, such as the University of Pretoria, even use this as the main form of community engagement (North-West University, Citation2016). Furthermore, the findings also suggest that universities could optimise their impact by empirically assessing the needs of given communities, and then tailoring their service and work-integrated learning activities to better articulate with these needs. Additionally, in light of the value of these activities, and given the limitation that the present study only assessed respondents’ general perceptions about the impact thereof, there would likely be significant merit in conducting studies aimed at assessing the specific impact of various individual service learning projects.

The NWU's science and engineering weeks, open days, sports weeks, training clinics, science centre, and botanical garden all appear to make a positive contribution to the NWU's communities. In terms of the broader relevance of this finding, it seems plausible to speculate that this impact is (at least in part) a result of giving communities access to university facilities, infrastructure, and expertise (which may otherwise be lacking in some of these communities). Several other universities were also able to show that their institutions provide important educational, cultural, social, and recreational opportunities and facilities to communities (Robinson et al., Citation2012; University of Birmingham, Citation2013). Events and activities of this kind not only provide universities with an opportunity to market themselves but also constitute important avenues to address issues surrounding relevance and social justice by allowing a broader section of their communities access to the university's knowledge and resources.

Finally, the number and quality of graduate and post-graduate students delivered by the NWU were also perceived as representing a significant positive contribution made by the university. Given that the NWU currently has around 34 000 students, this impact is likely to be fairly extensive and substantive. This finding also suggests that, for the NWU and likely also other universities, increasing the quality and/or the quantity of its graduates would constitute a relevant means to enhance impact. Whilst prevailing logistical and infrastructural conditions may limit the number of students that can be accommodated, efforts aimed at enhancing the quality of its graduates should be of central concern to any university, as such an endeavour speaks not just to its community-related contributions but also to its institutional aims.

Viewed comparatively, the most negatively perceived impact of the NWU pertained to the behaviour of contractors and service providers linked to the NWU and, to a lesser extent, the professional advice and support that individuals either receive or fail to receive from NWU staff (e.g. consultation services, experts serving on committees, etc.). This was particularly so in Mahikeng. Given that the aims of the present study centred on obtaining a broad baseline view of the perceived impact of the NWU, additional research would be required to ascertain exactly which contractors, behaviours, and elements pertaining to professional support and advice are perceived as being problematic. Professional discipline-based advice and support is linked to the NWU's ‘sharing of expertise’ model; something the university perceives as its main approach to community engagement. The NWU has around 130 of such experts (North-West University, Citation2017), most of whom are on an associate- or full-professor level. Their expertise covers almost all major disciplines. These experts could be made more aware of needs in the communities, and communities should be informed that these people exist in order to facilitate more effective engagement with the NWU's communities. Nonetheless, these findings also imply that a university's perceived impact (whether positive or negative) can also be measurably influenced not only by its own activities but also by its contractors, and that mechanisms should be considered to monitor the activities that such parties engage in in association with the university.

7. Limitations

As the study was cross-sectional in its design, no causal inferences can be made in relation to variables that have been found to be statistically associated with each other. Ideally, to assess impact, longitudinal and/or experimental studies would need to be conducted to determine the impact of specific community engagement projects and initiatives. Furthermore, the findings of the study reflect respondents’ perceptions of impact. Although such perceptions would serve as subjectively valid indicators of impact in terms of how this was personally experienced by participants, this approach has limitations, as existing impact that might derive from CE initiatives might not be perceived or recognised as such, or positive and negative impacts associated with factors other than such CE initiatives might be misattributed to such initiatives. A need exists to explore the potential of more empirically sensitive measures to supplement perceptual assessments.

8. Conclusion and recommendations

The findings of this study show that universities can indeed exert a positive impact in their communities, but highlight two important caveats. First, a university's outputs cannot necessarily be assumed to equate with or guarantee impact, and the findings illustrate that specific empirical assessment is required to determine the extent to which given outputs achieve a desired degree of impact, and also to better understand how various demographic subgroups in these communities are being differentially affected. Second, the findings imply that in order for universities to optimise their impact, they will have to ensure that their research, innovation, teaching-learning, and outreach activities are contextually relevant, and based on the actual needs of their communities (which has been shown to differ across regions in this study), and which would therefore ideally also need to be empirically assessed.

The findings of the study also suggest that community-based projects and services as well as service and work-integrated learning activities likely represent some of the most powerful and viable avenues for at least some universities to achieve impact in their communities, especially when such endeavours are specifically tailored to align with community needs. To a slightly lesser extent, significant impact also seems to ensue as a result of projects and initiatives such as science and engineering weeks, open days, sports weeks, botanical gardens, etc., which provide communities with access to university facilities, infrastructure, and expertise (which may otherwise be lacking in some of these communities). Events and activities of this kind not only provide universities with an opportunity to market themselves but also constitute important avenues to address issues surrounding relevance and social justice by allowing a broader section of their communities access to the university's knowledge and resources.

Furthermore, the findings also affirm that the quantity and quality of a university's graduate and post-graduate students, and consequently also any strategies aimed at enhancing such, will likely translate into substantive community impact.

Whilst additional research would be required to establish whether and to what extent the findings obtained in this study would be generalisable to the contexts of other South African universities, and also to quantify the various forms of impact assessed in this study in economic terms, it is hoped that the study will serve as an illustrative example of how universities could practically go about supporting their aim of fulfilling the mandate of the White Paper 3 on Higher Education Transformation of 1997 to contribute to social and economic transformation and development in South Africa (Council on Higher Education, Citation1997).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The term ‘community’ signifies a social grouping of society involved in an interaction at any given moment. Community refers to groups of people united by a common location, or to groups of people that are linked intellectually, professionally, and/or politically; that is, geographic communities, communities of interest, and communities of practice. This broad definition allows universities to focus on marginalised groupings in society whilst at the same time including other community formations and their activities (NWU, Citation2015a).

References

- Badad, S, 2010. The challenges of transformation in higher education and training institutions in South Africa. http://www.dbsa.org/EN/AboutUs/Publications/Documents/The%20challenges%20%20transformation%20in%20higher%20education%20and%20training%20institutio s%20in%20South%20Africa%20by%20Saleem%20Badat.pdf Accessed 9 June 2016.

- Bender, G, 2008. Exploring conceptual models for community engagement at higher education institutions in South Africa. Perspectives in Education 26(1), 81–95.

- Bhayat, A & Mahrous, MS, 2012. Impact of outreach activities at the college of dentistry, Taibah University. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 7(1), 19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2012.07.008

- CAISE, 2016. Information STEM education: Resources for outreach, engagement and broader impact. http://www.informalscience.org/sites/default/files/CAISE_Broader_Impacts_Report2016_0.pdf Accessed 9 June 2016.

- Cantor, N, 2012. Intensifying impact: Engagement matters. http://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1049&context=chancellor Accessed 9 June 2016.

- Centre for Higher Education Transformation, 2002. Transformation in higher education: Global pressures and local realities in South Africa. http://www.chet.org.za/books/transformation-higher-education-0 Accessed 8 June 2016.

- Coetzee, HC & Du Toit, I, 2011a. Integrated community needs assessment report for the North-West Province, South Africa. Unpublished research report.

- Coetzee, HC & Du Toit, I, 2011b. Community needs and assets in the NWP: A baseline study to guide future community engagement and interventions. Unpublished research report.

- Council on Higher Education, 1997. White Paper 3: A programme for the transformation of higher education. http://www.che.ac.za/media_and_publications/legislation/education-white paper-3-programme-transformation-higher-education Accessed 9 June 2016.

- Council on Higher Education, 2010. Community engagement in South African higher education. Kagiso 6.

- Council on Higher Education, 2014. White Paper for post school education and training. http://www.che.ac.za/media_and_publications/legislation/white-paper-post-school-educationand-training Accessed 8 June 2016.

- Council on Higher Education, 2016. South African higher education reviewed: Two decades of democracy. http://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/CHE_South%20African%20higer%20education%20reviewed%20-%20electronic.pdf Accessed 20 July 2016.

- Department of Higher Education and Training, 2011. Statistics on post-school education and training in South Africa: 2011. http://www.saqa.org.za/docs/papers/2013/stats2011.pdf Accessed 8 June 2016.

- Department of Higher Education and Training, 2016. Second national education Transformation summit, 15–17 October 2015, International Convention Centre, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal.

- Department of Higher Education and Training, 2017. Official website of the Department of Higher Education and Training. http://www.dhet.gov.za/SitePages/UniversityEducation.aspx Accessed 30 October 2017.

- Durban University of Technology, 2016. Official website of DUT. http://www.dut.ac.za/ Accessed 8 June 2016.

- Emfuleni Local Municipality, 2014. Official website of Emfuleni Local Municipality. http://www.emfuleni.gov.za/ Accessed 30 October 2017.

- Erickson, MS, 2010. Investigating community impacts of a university outreach program through the lens of service learning and community engagement. Iowa State University’s digital repository. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2840&context=etd Accessed 8 June 2016.

- Favish, J, 2015. Annexure 13: Research and engagement. 2nd National higher education summit, 15–17 October.

- Field, A, 2009. Discovering statistics using SPSS. SAGE Publications, London.

- Grobbelaar, S & De Wet, G, 2016. Exploring pathways towards an integrated development role: The University of Fort Hare. South African Journal of Higher Education 30(1), 162–187. doi: 10.20853/30-1-558

- Johnson, B, 2001. Toward a new classification of nonexperimental quantitative research. Educational Researcher, 30(2), 3–13. doi: 10.3102/0013189X030002003

- Kruss, G, 2012. Reconceptualising engagement: A conceptual framework for analysing university interaction with external social partners. Education and skills development: HSRC.

- Lazarus, J, Erazmus, M, Hendricks, D, Nduna, J & Slamat, J, 2008. Embedding community engagement in South African higher education. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 3(1), 57–83. doi: 10.1177/1746197907086719

- Mahikeng Local Municipality, 2017. Official website of Mahikeng Local Municipality. http://www.mahikeng.gov.za/ Accessed 30 November 2017.

- North-West University, 2015a. Official website for community engagement. http://www.nwu.ac.za/community-engagement Accessed 8 June 2016.

- North-West University, 2015b. New strategy and structure for the NWU. http://news.nwu.ac.za/new-strategy-and-structure-nwu Accessed 30 November 2017.

- North-West University, 2016. Website of NWU community engagement. http://www.nwu.ac.za/community-engagement Accessed 30 October 2017.

- North-West University, 2017. North-West University experts. http://news.nwu.ac.za/experts Accessed 30 October 2017.

- Ohme, AM, 2004. The economic impact of a university on its community and state: Examining trends four years later. University of Delaware. Unpublished research report.

- Parsons, RJ & Griffiths, A, 2003. A micro economic model to assess the economic impact of universities: A case example. AIR Professional File 87, 1–18.

- Robinson, F, Zass-Ogilvie, I & Hudson, R, 2012. How can universities support disadvantaged communities. file:///C:/Users/12894451/Downloads/disadvantaged-communities-and-universities full.pdf Accessed 20 July 2016.

- Seifer, SD, Shore, N, & Holmes, SL, 2003. Developing and sustaining community university partnerships for health. Research: Infrastructure requirements. Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, Seattle, WA.

- Seshoka, 2015. UKZN Touch Alumni Magazine. http://www.ukzn.ac.za/publications/UKZNTouch_2015.pdf Accessed 9 June 2016.

- Stats-SA, 2013. Millennium development goals: Country Report 2013. http://www.statssa.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/MDG_October-2013.pdf Accessed 9 June 2016.

- Steinacker, A, 2005. The economic effect of urban colleges on their surrounding communities. Urban Studies 42(7), 1161–1175. doi: 10.1080/00420980500121335

- Stellenbosch University, 2013. Transformation and diversity. https://www.sun.ac.za/english/Pages/Diversity.aspx Accessed 6 November 2017.

- Thakrar, JS, 2015. Re-imagining the engaged university: A critical and comparative review of university-community engagement. PhD thesis, University of Fort Hare.

- Tlokwe Local Municipality, 2017. Official website of Tlokwe Local Municipality. https://municipalities.co.za/south-africa/local-municipality/194 Accessed 30 October 2017.

- University of Birmingham, 2013. The impact of the University of Birmingham. Report by Oxford Economics. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/university/economic-impact-of-university-of-birmingham-full-report.pdf Accessed 13 February 2016.

- University of KwaZulu-Natal, 2017. The UKZN transformation charter. http://www.ukzn.ac.za/wp-content/miscFiles/docs/general-docs/the-ukzntransformation-charter.pdf Accessed 30 October 2017.