ABSTRACT

The majority of the population living in the informal settlements of Windhoek, Namibia, have limited access to public municipal services. This paper integrates results from a sample of 97 randomly selected households, interviews with experts and community leaders and review of literature to describe and analyse the relationship between land tenure and municipal services in the informal settlements. Findings from our study show that formalised land tenure is a condition for households to access municipal services privately. However, 85% of the sample of the households in the informal settlements do not own land under current land tenure policy. Further, the need for communities ‘to own land’ seemed more immediate and pressing compared to water access, which is seen as a way to govern themselves towards raising funds for land acquisition. But lack of land ownership remains a constraint.

1. Introduction

Namibia gained independence in 1990 after being governed by two colonial regimes during most of the twentieth century. During the colonial period, there were strict limitations on movement and the majority of the black people were confined to demarcated reservations across the country and within certain areas of the big cities (Karuaihe et al., Citation2012; World Bank, Citation2002). After independence, demolition of ‘the former compounds’ (where contract workers were accommodated to provide cheap labour), combined with the upgrading of the former ‘single quarters’ and rural–urban migration, contributed to the creation of the informal settlements at the outskirts of the big cities, including the capital, Windhoek. This led to an increase in demand for accommodation, which could not be met by the existing structures and demographic setup prior to independence. Therefore, informal settlements are seen as an alternative cheap accommodation for those who cannot afford a place in the formal settlements.

Frayne (Citation2007) showed that over 40% of the rural–urban migration to Windhoek occurred during 1990–2000. The majority of these people moved to Katutura,Footnote1 a high density suburb where the majority of blacks reside. This is the area where most of today’s informal settlements are located. Today, these informal settlements constitute what has been termed ‘the unconnected segment’ of the water market (Karuaihe et al., Citation2012), which refers to consumers who access water and sanitation through communal facilities controlled by Water Point Committees (WPCs). The WPC belongs to a Water Point Association (WPA) and is self-organised and elected by the communities. Specifically, our study found that 82% of sampled households accessed water through a WPC, while 18% used prepaid metered cards. Even though this is a large proportion of people with access to mainly water (no other services are rendered, except public toilets in some areas), such access is limited due to lack of access to land. The main issue here is ‘land’ and other services, since these households cannot have private services due to lack of a title on the land they put their dwellings.

There are a limited number of scientific studies about the informal settlements in Windhoek, covering a range of topics (World Bank, Citation2002; Bryant et al., Citation2004; McClune, Citation2004; Frayne, Citation2007; Mooya & Cloete, Citation2007; de Vries & Lewis, Citation2009; Ulrich & Meurers, Citation2015). The contribution of this paper concerns access to utilities, especially water, by poor households in urban, informal settlements, in relation to land tenure. The paper integrates original data from a survey of 97 randomly selected households and a series of focus groups and key informant interviews conducted by one of the authors. In addition, grey literature and other documents are reviewed to describe and analyse the relationship between land tenure and municipal services in the informal settlements.

Poor households in the informal settlements of Windhoek do not have access to land in the formal settlements of the city. In fact, almost all of the households living in informal settlements do not own land. Specifically, we found only 15% of our sample households qualified to lease plots from the City Council, leaving 85% without any formal title on the land they occupy. This was due to a lack of proper legislation for council to allocate land. The proposed Urban and Regional Planning Bill has been in legislation (Ulrich & Meurers, Citation2015) for a long time since inception in the early 2000s. This left most residents of the informal settlements in a kind of legal limbo, without clear title but provisionally tolerated by government. Mooya & Cloete (Citation2007) described them as ‘extra-legal’ using the New Institutional Economics framework by de Soto. The lack of appropriate policy and regulatory framework affect land allocation in Namibia in general, and in the urban areas in particular, as government has been relying on an outdated colonial Act (Weylandt, Citation2018).

Nevertheless, the Urban and Regional Planning Bill has been passed by Parliament in December 2017 (Beukes, Citation2017; Weylandt, Citation2018). We believe this legislation would enable government and the Windhoek City Council to regularise informal settlements and provide title for land ownership for households in those areas. This should ease the burden of access to services and provide room for individual municipal services. This is a potential area for future research to explore the impact of policy on access to service and resources including land.

2. Some existing literature

Informal settlements are characterised as areas where: (i) inhabitants live with no security of tenure on the land they inhabit – with squatting or informal rental options; (ii) the neighbourhoods usually lack basic services and city infrastructure and; (iii) the housing may not comply with planning and building regulations, and is often situated in geographically and environmentally hazardous areas (UN Habitat, Citation2003). The emergence of informal settlements seems to be a common phenomenon in most African cities and many developing countries – even in richer countries, though in qualitatively different degrees. A major factor in the creation of these informal settlements is the legacy of the limited access to urban land enforced by the colonial regimes. The labour laws of most colonial governments in Africa limited the number of indigenous Africans permitted in urban areas. This practice can be viewed as a ‘taking of land’ from the original occupants and vesting it in an elite few (Kironde, Citation1995; Oladokun et al., Citation2010). The colonial regimes of Namibia followed this policy – particularly in the capital Windhoek – leading to the post-colonial urban in-migration noted earlier. The consequence is a challenge for the current authorities to provide infrastructure for the numerous new settlers (World Bank, Citation2002; Frayne, Citation2007).

The legacy of colonial policy along with the rapid population expansion of the post-colonial period has intensified effective urban land shortages. The erratic settlement of the population influx, together with inadequate institutional structure, has resulted in insecure land tenancy. The urban poor have financial and other resource constraints that drive them to the informal land market (Brown-Luthango, Citation2010; Oladokun et al., Citation2010, Twarabamenye & Nyandwi, Citation2012; Durand-Lasserve, Citationundated). This informal (grey) market works through ‘a simple sale contract’ between buyer and seller, without formal registration with the authorities. In many African countries, such informal trading often leads to the destruction of settlements in the name of ‘illegal land occupation or trespassing’ (Oladokun et al., Citation2010). Since the informal structures themselves are deemed illegal, this could lead to possibly fraudulent sale contracts. Therefore, it is necessary for African governments to enable land markets to become more transparent and efficient (Kironde, Citation2000; Oladokun et al., Citation2010; Twarabamenye & Nyandwi, Citation2012), for mutual benefits. Advocates suggest that the informal land market be institutionalised to a level which improves access to ‘legal’ land in peri-urban areas (Twarabamenye & Nyandwi, Citation2012; Durand-Lasserve, Citationundated). A similar approach is advocated by Kombe (Citation2000), who suggests governments recognise the ‘flourishing’ informal land and housing market and identify the opportunities to improve such markets.

Unfortunately, effective government action is not easy, and sometimes government actions have made matters worse. For example, in Mali, Durand-Lasserve et al. (Citation2013) found that land acquisition is a complex process involving various channels of ‘land transformation and administrative allocation of residential plots to households’. This complex process makes access to land costly and insecure, which results in negative social and economic impacts over the long term. Similarly, de Vries & Lewis (Citation2009) found that the various Acts and regulations in efforts to regularise land in Namibia have generated complexity rather than a solution for urban land tenure problems. In South Africa, limited access to land is a major constraint for the urban poor to access housing and other economic opportunities despite several policy interventions by government (Planact, Citation2007; Brown-Luthango Citation2010). They showed complexity of the role of government at different levels, with conflicts between the Provincial Government and the Johannesburg City Council, when it comes to land planning and development and their respective mandates and development objectives. This conflict over land allocation left the poor with very few options for residential settlement through the National Housing scheme under the Gauteng Provincial Government (Planact, Citation2007). These findings are similar to the Windhoek experience, where the City Council blames the national government for lack of appropriate policy on land formalisation, while central government relies on council for service provision and on the National Housing Enterprise (NHE) for housing loans to the urban poor.

Land allocation challenges are global, but often especially intense in the developing world given their low level of income and market inefficiencies, coupled with lack of appropriate policies to address the challenges. About 25% of developing countries have legal impediments preventing women from accessing land and finance in their name (UN, Citationundated). Often women seem most burdened by lack of access to land and property. Developed countries ‘are not immune to urban disparities among their populations’ (UN Habitat III, Citation2015). Therefore, responses to the issues are also global. Thus, some of the European countries experienced increases in the rent costs for the urban poor who cannot afford decent housing, particularly in large cities – with 6% of their urban dwellers said to be living in very poor conditions (Economic Commission for Europe, Citation2008). The situation has been aggravated by migration in recent years. Further, evidence from other developed countries (Sweden and Denmark) showed that increases in income levels enabled women to acquire land and other property, which was supported by enabling legislation (UN, Citationundated). One of the best models is the ‘Union de Vecinos’, from Los Angeles (LA), USA. This civil organisation was formed by women from two of the city’s poorest neighbourhoods, who responded to threats of demolition of their houses by the local government. Their efforts led to the adoption of a moratorium on the demolition of low income housing in LA (UN, Citationundated).

Earlier, we discussed the central role of colonial heritage in creating these urban land access and poverty issues, but other factors have played important roles, most obviously, the accelerated population growth and rural–urban migration since the end of World War II. The increase in the number of people without access to basic services in urban areas is directly related to the rapid growth of slum populations in the developing world, and the inability (or unwillingness) of local and national governments to provide adequate water and sanitation facilities to these communities. The absolute number of slum populations increased from 650 million people in 1990, and is estimated to reach nearly 900 million by 2020 (UNESCO, Citation2015). This trend put pressure on service delivery despite some improvements, evidenced by the achievement of the global Millennium Development Goals (MDG) target for slum dwellers (UN, Citation2012). Further, over 90% of urban population growth comes from the developing world, with the world’s poorest regions expected to experience double population growth (World Bank, Citation2008). More than half the urban population of Africa live in slums, compared to Asia with 30% and Latin America at 24% (UN Habitat, Citation2014).

In Namibia, the Windhoek population was 325 858 in 2011, accounting for 15% of the total Namibian population of 2.1 million (Namibia Statistics Agency, Citation2013). According to the Windhoek City CouncilFootnote2 estimates, informal settlers constituted 29% of the Windhoek population in 2004. Further, Bryant et al. (Citation2004) found that, in 1997, the City of Windhoek had 8171 registered households from the informal settlements, of which 27% were serviced with communal services leaving the majority of these households without municipal services. These results and the poverty dynamics of informal settlements show that although council has been responding to the increasing demand for services due to population increases, the types of services, and thus, the quality offered to informal settlements remained relatively the same – poor. Mainly communal water, limited sanitation and street lights are offered to the urban poor. See for comparison of infrastructure over a decade.

3. Methods and data

The study used a sample frame from the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) of Namibia, based on the Enumeration Areas (EAs) of the 2001 Census. Maps for each EA were obtained from the geographic information system (GIS) division in the CBS. The City of Windhoek is stratified by three levels of income: high, middle and low based on the housing characteristics and geographic location, and we followed this stratification for our study. The primary sampling unit (PSU) was selected from the sample frame, while the second stage sampling unit was selected from a complete list of households within the selected PSU. We prepared the household list during the fieldwork before the interviews (see Karuaihe et al., Citation2012 for details).

This paperFootnote3 uses primary data on a sample of 97 randomly selected households from informal settlements in Windhoek, Namibia, using quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection. The main source of data is interviews with the households in addition to key informant interviews with officials from the City Council. Further, we conducted a series of focus group discussions (FGDs) with communities in the informal settlements. For the purpose of this paper, we are reporting on responses from three FGDs with members of the WPCs and, community members. The FGDs include: (i) a meeting with communities using a prepaid meter system (18% of the sample); (ii) an FGD with the WPC for communities accessing water through managed communal water points; and (iii) a meeting with a WPC managing water for communities who are leasing plots from council (15% of the sample). The last group organised themselves to acquire big plots, which they were able to subdivide among members for each household to lease a plot from council. This group paid N$85 in 2004 per month for lease and water, compared to the N$20 paid for water only. Noteworthy is that all households accessed communal standpipes including those using prepaid cards. The difference is that their access is not controlled by a WPC since they use the card to access water based on the units loaded. presents a photo of a prepaid water meter system.Footnote4

Figure 1. Prepaid water meter system.

Source: Photo taken by the author (Karuaihe) during data collection in 2004.

The FGDs included both men and women, with two of the WPCs having women as active members of the community. Main information collected through FGDs was about the structures and the role of the WPCs. This provided in-depth information of work done by the WPCs versus work by council, particularly the collection of fees and controlling access times. A common feature among the respective WPCs is that all informal settlers access services through the WPCs. This implies that all communities operate through some form of institutional arrangements guided by a WPC irrespective of their mode of access, e.g. prepaid, communal or even those leasing plots from council. This is an indication of effective institutional arrangements – elements of social cohesion and the need to belong to a group, as it provides collective benefits for communities. The informal settlements The two photos in are deleted due to low resolution and are not affecting the flow of the paper. Authors don't have access to the original photos and are not able to change the resolution as required. The removal of maps does not affect the content of the paper as they are only referred to it in this section and has been edited accordingly covered in the study are: Hakahana (prepaid meter area); Babylon, Okuryangava (Okahwe street), Havana, Okahandja Park (Helao Street) and One Nation.

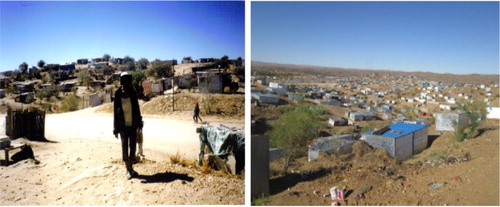

Figure 2. Photos of informal settlements: pre- and post-survey period. (a) Informal settlements in 2004 (b) Informal settlements in 2014

Source: Karuaihe (2004).

Source: Nangombe (Citation2015).

The two photos presented in a and b show that there has been little progress in terms of development in the informal settlements between 2004 and 2014. The first photo was taken by the author (Karuaihe) in 2004 during data collection. The second photo comes from Nangombe (Citation2015). Considering the little improvement in infrastructure and service delivery, we believe that the 2004 data still present issues worth investigating.

The main group (82% of sample) access water through communal standpipes irrespective of their land tenure status. Informal settlement households covered in the study can be classified according to two types. (a) An ‘undeveloped area’ constitutes two types: one area referred to as (i) ‘Resettlement’ – refers to an area where households are resettled ‘non-voluntarily’ from another area due to the former area being upgraded for lease and other services, or due to those resettled households’ failure to honour their commitments towards monthly group contributions. Another area (ii) Non-lease group, where people settled by themselves and council was ‘obliged’ to provide basic services of water through communal points. (b) The developed unconnected segment of the water market consists of those households who raised enough funds to lease plots from council, either as individuals or as a group. Since the communities who are leasing plots from council seem to enjoy some other services like ‘serviced roads’ in a demarcated area, we classify such an area as developed, compared to the other areas. These groups or individual households can access water as a group through communal water points or prepaid meter systems.

4. Discussion

We found that 85% of the households had access to water through the WPC – and to limited sanitation. About 18% of the sampled households accessed water through prepaid meters. This implies that over 80% of the sampled households are serviced mainly with water and no other services are rendered, except public toilets in some areas. Comparing our results to Bryant et al. (Citation2004) and other related studies, we show that there has been little or no progress in the type of services offered to informal settlements over time, despite the increase in coverage. This is an indication that council is only responding to an increase in demand, but the ‘quality and type of services’ offered remained relatively the same (see ).

Communities in informal settlements in Windhoek access water through institutional arrangements, by a WPC. The role of the WPC is to collect monthly fees from their members, manage the communal water points and control access of members who belong to their WPA. The monthly fee was N$20 each per household in 2004 and it was understood to be mainly for water. In principle, the monthly fees and the rules that govern it are agreed upon by all members of the WPA. In our study, the general consensus was that all members support the institutional arrangement and its governance structure, despite some defaults on payments. The rules of governance also include agreement on how to handle surpluses or shortfalls in a particular month. Our findings show that the need for land ownership was more immediate and pressing compared to water access, which communities saw as a way to govern themselves towards land acquisition. In view of this, communities would agree to save any surplus towards land acquisition and/or organise themselves to save money towards land ownership.

The relationship between council and the WPC is quasi-formal and not legal or binding in any way. The City Council charges a flat rate per cubic metre (m3) for water in the informal settlements, with the first 6 m3 provided for freeFootnote5 to households in these areas given their low income levels. Council argued that it ‘was going out of its way’ to assist the communities where possible, especially in guiding them with governance of the institutional arrangements, such as monthly meetings, record keeping and reporting. The monthly fee of N$20 was understood to be sufficient to cover the municipal bill from both the WPC and council. According to council, ‘they were assisting’ the communities despite the lack of a proper enabling framework or policy, due to lack of the Urban and Regional Planning Bill, which was only enacted in December 2017 (Beukes, Citation2017; Weylandt, Citation2018).

Council seems to be putting the blame on central government due to lack of policy, while government leaves the responsibility of service delivery to the City Council. Despite the back-and-forth between the different layers of government, land tenure formalisation is a requirement for the communities to access private municipal services. Where council provide private municipal services to households, such households would receive a municipal bill and pay the fees to council. But, in the case of informal settlements, communities use their own resources to ensure that the collective bill for communal water is paid by all members who access that water point. The City Council finds this method more efficient and reliable than dealing with individual households. This is due to the fact that it is less costly and more convenient for council to deal with the WPC than with individual households, who may fail to honour water payments given their low levels of income. The WPC approach is also efficient in ensuring that water payment is done on time, without council having to cut off households who fail to pay. It is in view of this that we believe the WPC performs the duty of council of collecting fees from its members and paying the total for a collective water bill to council. While there could be mutual benefits in this arrangement, such as council acting as a banker for the urban poor – in terms of savings for their contributions towards leasing of plots – it is clear that the WPC is carrying that burden of ensuring that monthly water fees are paid on time. In cases where the collected amount is greater than the monthly water bill (based on meter readings by council), the WPC pays all the money collected and keeps a surplus with council.

According to the WPCs, having a surplus with council is more common than having a shortage for water payment. This implies that communities entrust their money with the WPC, which in turn relies on trust from council instead of saving the extra money collected with banks to earn interest. The City Council uses the surplus payment from one month to cover ‘any shortage’ in future months, where the bill exceeds the monthly contributions. In some cases, the extra funds collected are believed ‘to be kept with council as savings for securing land in future’. While such arrangements may be working, the implications are that council ‘acts as the bank for these communities’. However, council has control over the bill as well as the allocation of the extra funds as it deems fit. This shows there is uneven power in decision-making between communities and council. Communities do the work of collecting the fees and managing the water points, but they have limited say in the allocation of the money collected.

Unlike the WPC in rural communities where members are paid for work done, members of the urban WPC are volunteers and are not paid. In rural Namibia – as in some other parts of the developing world – power has been devolved to the regions, giving community institutions like the WPCs some formal recognition. Thus, in the rural areas of Namibia, the WPCs are recognised as formal structures of the Regional Councils and, therefore, members have more power to manage the rural water points. However, in Windhoek and other major cities, the urban WPCs are self-organised and quasi-formal. Although they manage the water points like in the rural areas, they are not a formally recognised part of local governance. As a result, the City Council takes advantage of this arrangement and the lack of policy to accelerate the upgrading of informal settlements. It is therefore necessary for this informal structure to be recognised and formalised into local government structures, not only to acknowledge the role of the WPCs, but also to ensure sustainability of the communal water points with rewarding systems (for the WPC) in place. Formalisation of the community informal structures and self-selected institutional arrangements can enhance better working relations between council and the communities for mutual benefits. With the enactment of the Urban and Regional Planning Bill of 2017, we believe the City Council now has an enabling framework to accelerate the upgrading of informal settlements and to address the issue of land tenure to these communities as it remains a binding constraint for them to access other services.

Furthermore, the communities also establish committees for land, which are responsible for collecting voluntary monthly contributions from community members. In some cases, the funds raised for collective land acquisition are saved at local banks towards the purchase of plots from council. Although the communities understand the savings are for purchase of plots from council, the lack of appropriate policy does not allow communities to hold a title deed on the land. However, this arrangement allows council to lease plots to individuals or groups who have raised enough money to serve as collateral instead of selling them for private ownership. Since only a few households can be resettled to an upgraded area, some of the households living in an undeveloped area can be relocated to another settlement depending on ‘their standing with the community’ – based on whether their payments are up-to-date. Those who are in good standing can qualify to be relocated to upgraded settlements where they can lease plots from council through group savings or they can qualify for a loan. According to community respondents, those households who are not in ‘good standing’ can be relocated ‘forcefully’ to undeveloped areas identified by council.

This situation is challenging since the WPC has the responsibility of identifying the households to be relocated. Forceful relocation seems to be well understood by the communities, and households already know who are likely to be relocated. For those individuals who are willing and able to buy plots individually, council can sell them plots in the formal settlement, and as a result relocate them out of the group to the connected water segment of the market. The problem with this arrangement is that the poorer residents find it costly to relocate to the ‘formal or upgraded settlements’ and fear that they might be facing higher costs in the new settlements. This is what Berner (Citation2000) referred to as losing advantage as informal settlers, who could occupy the land ‘illegally’. Residents who wish to improve their circumstances have only two options: to ‘live within a group’ (belong to a community association), or face the higher costs that come with land tenure formalisation if one relocates.

The present fuzzy land policy is advantageous to council, reducing the incentive for reform. The Namibian central government relies on the City Council for services provision and the NHE for the provision of low cost housing loans to the communities. It is not clear whether the lack of a coordinated approach by central government is due to its inability to perform its function or whether the lack of policy is the main factor. In turn the City Council relies on the self-organised WPCs to administer many aspects of water delivery in the informal settlements. Even access to loans through the NHE requires collateral that would enable them to qualify for group loans. However, many are later evicted when they are unable to honour their monthly instalments (Maletski, Citation2001). Nevertheless, council allows households to organise themselves into groups and contribute towards land acquisition – known as Shack Dwellers Associations. Experience from the Shack Dwellers International (SDI) shows that a proactive approach from the communities works better than waiting for government (Narismulu, Citation2003). This is similar to the initiative taken by some household groups in the informal settlements covered in this study.

Finally, it is important to note the active role that women play in the WPCs. Buruah (Citation2004) argues that in many parts of the world women tend to be marginalised and excluded from the formal regulations of land and that policy-makers should take into account the role of women when formalising land tenure. The complex role of the WPCs illustrates why authors such as Durand-Lasserve (Citation1996) argue that it is important for authorities to understand the complex social structures of informal settlements before implementing upgrading projects. Policy-makers also need to get communities involved in the design of the municipal services including community understanding and ‘buy-in’ to the management costs the local residents will bear so that services can be affordable to them (Fourie, Citation2001).

Even though the focus of our paper is not directly on land, but on municipal services that depend on land tenure, the debate on access to land and related services needs to be given attention, both in terms of policy as well as academic discourse. The issues of land access in general and for the urban poor in particular, have recently made news headlines in Namibia. Some critics are calling for government to pay more attention to the land debate. The recent debate on land allocation came to the fore under the rubric of ‘Affirmative Repositioning’ (AR), which mobilises the youth and other Namibians to ‘occupy’ land, seen as ‘illegal and destabilising’ by the Namibian Authorities (Disho, Citation2015; News24, Citation2015; Goeieman, Citation2016; Cloete, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). The above news headlines and debates bring the issues of land allocation and access for the poor to academic discourse, calling for closer robust debates around the issue. Since the issue of land is seen as an urgent social developmental need, it needs serious consideration by the authorities and all the relevant stakeholders. Therefore, there is a need for more scientific studies to strengthen the debate on access to resources, such as land and municipal services and to provide research-based evidence, which is part of the contributions by this paper.

5. Conclusions

The issue of lack of access to land and its effect on access to municipal services is one of the key findings of this paper. However, whether land formalisation through policy will improve access to municipal services, remains an empirical issue that requires further research. Poor households may still need to acquire loans and credit to buy land, which can become another constraint given their low income and limited employment opportunities. De Vries & Lewis (Citation2009) noted that the degree of land tenure regulation and regularization is perhaps not so much a solution for urban land allocation, but more of a problem itself. The problem is aggravated by the fact that some of the national policies and regulatory frameworks are centralised at national level, while implementation is at the local level where the City Council has to play a role.

Further, there are other benefits of belonging to a community group association, including collective security through membership and information sharing. Such benefits were also observed in other studies on Windhoek informal settlements. For example, members share information on available plots for sale (Mooya & Cloete, Citation2007). With respect to the role of the Namibian government with regard to the upgrading of settlements, it is not clear. It appears that communities have to deal mainly with the City Council except that those who can afford to buy legal plots through credit can deal with the NHE. The resulting situation is complex and ambiguous. Namibia’s situation is similar to others in Africa and elsewhere. For example, Durand-Lasserve (Citationundated) found that the declining trend of serviced land and public housing in most Africa countries is due to a number of factors, such as lack of political will, corruption and capacity challenges in the public sectors. Experience from other countries has shown that conflicting mandates at different levels of government can be a challenge. Some of the proposed alternative solutions to the land debate in Africa include public–private partnership in land provision, while others suggest that African governments should consider allocating funds for collective land acquisition to improve access to land for the poor. For example, the Tanzanian government land policy is aimed at the poor, yet they still lack access to land (Kironde, Citation1995).

The land debate and access to land for the poor is a big issue for many African countries, and remains a challenge many years after colonisation. While Namibia is one of the youngest democracies in Africa, addressing its land question would assist the government to achieve more in terms of nation building through the attainment of the national development goals. With the land allocation debate, including ‘urban land’ becoming an issue of contentment – especially to the youth, the Namibian government needs to reconsider its approach and update or introduce relevant policies to address it and fulfil the aspirations of independence for its people.

The fact that formalised land tenure is a condition for households to access municipal services privately, while the majority of the households in the informal settlements do not own land, is a challenge to economic development. This remains the main constraint for the affected households and also to the Namibian government, both for moral-ethical reasons and for the practical issues of facilitating economic development. In the Namibian situation, it appears that the way the majority of communities can fulfil their dream of owning land is to self-organise – to establish local institutions and gather individual contributions to buy land collectively. These findings suggest that successful government programmes should support groups rather than an individual approach to supplying services for the urban poor. However, group approaches impose costs on individual households who incur ‘costs’ of distance and waiting time in accessing communal services rather than a residential point of municipal services. Costs can also include safety issues for vulnerable groups like women and children when walking to access services at night and other odd times. Without supervision of the WPC the system is also subject to vandalism.

We conclude with some policy recommendations and observations. For the affected communities to benefit from upgrading of their settlements, all stakeholders including government and the private sector should participate in the programme. If the Namibian government wants to improve the living conditions of the urban poor, they need to introduce policies that recognise the complex nature and relations of informal settlements. Certainly the availability of credit is a factor. In Namibia, some urban poor can eventually get loans from the NHE, based on collateral. One approach might be to establish a partnership between the affected communities, the loan and service providers (including the private sector) as well as government, after establishing clearly the rates that are affordable to these communities and the term of payments (Fourie, Citation2001).

The current study is based on a survey that addressed access to water and other services by the low income communities of Windhoek, Namibia. There is a need for future research to focus on specific issues of settlement upgrading and its implications for service delivery. Nevertheless, the main issue to resolve ‘the current empirical puzzle’ lies in the formalisation of the land policy for informal settlements in Windhoek. In general there seems to be mutually expected benefits among the communities and even with the City Council. While such benefits might be more in favour of council, it is beyond the scope of this study to determine the impact of the institutional arrangements. We believe the new policy would guide all parties towards clear mutual benefits, which will be sustainable in the long term.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Selma T Karuaihe http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1453-7979

Notes

1 The term, Katutura (a segregated township by ethnic group during the colonial and Apartheid era) is derived from an Otjiherero phrase meaning ‘a place where people don’t want to live’ – referring to the refusal of the Windhoek black people when they were forcefully removed from the ‘Old Location’ (modern day Hocland Park, an upmarket suburb in Windhoek). Katutura was created in 1961 following their forced removal (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Katutura).

2 This information is based on interviews we conducted with officials from the City Council in 2004.

3 This paper draws from a study that covered a sample of 330 households in Windhoek, looking at three different income categories (high, middle and low). This paper focuses on the low income households of the main study. The data were collected in 2004. The authors have been looking at water issues in Windhoek and continued to engage literature and some stakeholders on pertinent issues. Observations and literature show that urban poverty continues with informal settlements serviced with mainly water to date. We therefore believe that the data of 2004 and the issues raised then are still relevant to this paper.

4 These households buy water in advance using a card loaded with money for a certain amount of water as per user’s demand. It works like any prepaid service, e.g. electricity or mobile phone.

5 This is part of the Free Basic Services provided to low income households by the City Council.

References

- Berner, E, 2000. Informal developers, patrons, and the state: Institutions and regulatory mechanisms in popular housing. http://n-aerus.net/web/sat/workshops/2001/papers/berner.pdf Accessed August 2004.

- Beukes, J, 2017. Regional land bill passed. The Namibiansun newspaper, 29 December. https://www.namibiansun.com/news/regional-land-bill-passed2017-12-29 Accessed 3 March 2018.

- Brown-Luthango, M, 2010. Access to land for the urban poor—Policy proposals for South African cities. Urban Forum 21, 123–38. doi: 10.1007/s12132-010-9081-x

- Bryant, AM, Campbell, AD & Salmon, JP, 2004. Development of communal washing facilities for the Northwest settlements of Windhoek, Namibia. Worchester Polytechnic Institute and the City of Windhoek, Windhoek, Namibia.

- Buruah, B, 2004. Challenges and opportunity in land ownership for women in the informal sector in urban contemporary India. The ethics of development induced displacement project, working paper #3. York University, Centre for Refugee Studies.

- Cloete, L, 2016a. Nama leaders back Swartbooi. The Namibian, 8 December, p. 1. http://www.namibian.com.na/48944/read/Nama-leaders-back-Swartbooi Accessed 16 December 2016.

- Cloete, L, 2016b. SwartbooiG refuses to apologise. The Namibian, 12 December, p. 1. http://www.namibian.com.na/49070/read/Swartbooi-refuses-to-apologise Accessed 16 December 2016.

- de Vries, W & Lewis, J, 2009. Are urban land tenure regulations in Namibia the solution or the problem? Land Use Policy 26, 1116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.02.002

- Disho, J, 2015. The land issue in Namibia. New Era, 31 July. https://www.newera.com.na/2015/07/31/land-issue-namibia/ Accessed 16 December 2016.

- Durand-Lasserve, A, 1996. Urban management and land regularization and integration of irregular settlements: Lessons from experience. UNDP/UNCHS (Habitat)/World Bank, Working Paper #6, May 1996.

- Durand-Lasserve, A, undated. Land for housing the poor in African cities. Are neo-customary processes an effective alternative to formal systems? Laboratoire SEDET Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Université Denis Diderot, Paris, France. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTURBANDEVELOPMENT/Resources/336387-1268963780932/6881414-1268963797099/durand-lasserve.pdf Accessed July 2017.

- Durand-Lasserve, A, Durand-Lasserve, M, and Selod, H, 2013. A systemic analysis of land markets and land institutions in West African cities. Rules and practices: The case of Bamako, Mali. The World Bank Development Research Group, Environment and Energy Team. WPS6687 Public Policy Research Working Paper 6687. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/889891468049214422/pdf/WPS6687.pdf Accessed July 2017.

- ECE (Economic Commission for Europe), 2008. Committee for housing and land management in search for sustainable solutions for informal settlements in ECE region. http://.unece.org/index.php?id=38779 Accessed 27 July 2017.

- Fourie, C, 2001. The use of new forms of spatial information, not the Cadastre, to provide tenure security in informal settlements. Paper presented at the International Conference on Spatial Information for Sustainable Development, 2-5 October, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Frayne, B, 2007. Migration and the changing social economy of Windhoek, Namibia. Development Southern Africa 24(1), 91–108. doi: 10.1080/03768350601165918

- Goeieman, F, 2016. Clinton tears into Nujoma. Namibiansun, 6 December. https://www.namibiansun.com/news/clinton-tears-into-nujoma/ Accessed 16 December 2016.

- Karuaihe, ST, Wandschneider, P, and Yoder, J, 2012. Estimation of the water bill, when water price is cryptic: An analysis of the different water market segments in Windhoek, Namibia. South African Journal of Economics 80(2), 264–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2011.01293.x

- Kironde, JML, 1995. Access to land by the urban poor in Tanzania: some findings from Dar es Salaam. Environment and Urbanization 7(1), 77–96. doi: 10.1177/095624789500700111

- Kironde, JML, 2000. Understanding land markets in African urban areas: the case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Habitat International 24, 151–65. doi: 10.1016/S0197-3975(99)00035-1

- Kombe, JK, 2000. Regularizing housing land development during the transition to market-led supply in Tanzania. Habitat International 24, 167–84. doi: 10.1016/S0197-3975(99)00036-3

- Maletski C, 2001. NHE presses on with eviction, Windhoek, The Namibian, 19 March. http://www.namibian.com.na/archive19982004/2001/March/news/01DD70A114.html Accessed August 2004.

- McClune, J, 2004. Water privatisation in Namibia: creating a new apartheid? LaRRI (Labour Resources and Research Institute), Windhoek, Namibia.

- Mooya, MM & Cloete, CE, 2007. Property rights, land markets and poverty in Namibia’s etra-legal settlements: An institutional approach. Global Urban Development 3(1), 1–23. http://www.globalurban.org/GUDMag07Vol3Iss1/Mooya.htm Accessed 9 December 2016.

- Nangombe, 2015. High-resolution mapping of land use change and urban sprawl by means of remote sensing and GIS: A case study of Goreangab township. Windhoek. http://www.the-eis.com/data/literature/L%20R%20Nangombe_Honours%20Mini_Thesis_2015-01-29.pdf Accessed 1 March 2018.

- Narismulu, P, 2003. Examining the undisclosed margins: Post-colonial intellectuals and subaltern voices. Cultural Studies 17(1), 56–84. doi: 10.1080/0950238032000050832

- NSA (Namibia Statistics Agency), 2013. Namibia 2011 population and housing census indicators. The Republic of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia.

- News24, 2015. Namibia mass land action urged. News24, 23 January. http://www.news24.com/Africa/News/Namibia-mass-land-action-urged-20150123 Accessed 9 Dec 2016.

- Oladokun, TT, Gbadegesin JT & Odebode AA, 2010. Enhancing access to land by the urban poor: Exploring viable alternatives. http://www.academia.edu/3366953/ENHANCING_ACCESS_TO_LAND_BY_THE_URBAN_POOR_EXPLORING_VIABLE_ALTERNATIVES Accessed July 2016.

- PlanAct, 2007. Urban land: Space for the poor in the City of Johannesburg? Summary of findings of a 2007 joint Planact/CUBES study on Land Management and Democratic Governance in the City of Johannesburg. http://www.planact.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/2.-Urban-land-Space-for-the-Poor-Research-Summary.pdf Accessed July 2017.

- Twarabamenye, E & Nyandwi, E, 2012. Understanding informal urban land market functioning in peri-urban areas of secondary towns of Rwanda: Case study of Tumba Sector, Butare Town. Rwanda Journal 25, 34–51. doi: 10.4314/rj.v25i1.3

- Ulrich, J & Meurers, D, 2015. The land delivery process in Namibia. A legal analysis of the different stages from possession to freehold title. In Carlowitz, L & Middleton, J (Eds.), In cooperation with advisers. GIZ Support to Land Reform. http://www.the-eis.com/data/literature/The%20land%20delivery%20process%20in%20Namibia.pdf Accessed July 2016.

- UN Habitat, 2003. The challenge of slums. Global report on human settlements. https://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2003/07/GRHS.2003.6.pdf Accessed 20 July 2017.

- UN Habitat, 2014. Slums and cities prosperity index (CPI). http://cpi.unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/resources/City%20Prosperity%20Index%20-%20Ethiopian%20City%20Addis%20Ababa.pdf Accessed 20 July 2017.

- UN Habitat III, 2015. Habitat III issue papers: 22 – Informal settlements. New York. https://unhabitat.org/habitat-iii-issue-papers-22-informal-settlements/ Accessed 27 July 2017.

- UN (United Nations), 2012. The Millennium Development Goals report, 2012. United Nations, New York.

- UN (United Nations), Undated. UN. Urban Shelter: Women’s property rights. www.un.org/ga/Istanbul+5/34.pdf Accessed, 27 July 2017.

- UNESCO, 2015. The United Nations world water development report 2015.

- Weylandt at IPPR, 2018. Key bills in 2017: Year in review 2017. Perspectives on parliament: Issue No. 9, February 2018. http://ippr.org.na/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/POP_YearReview_WEB.pdf Accessed 1 March 2018.

- World Bank, 2002. Upgrading low income urban settlements: Country assessment report, Namibia. The World Bank AFTU 1 & 2.

- World Bank, 2008. Urban poverty. World Bank Urban Papers, 2008. Washington, DC.