ABSTRACT

Innovation for inclusive development (IID) is widely promoted as a policy objective in the global South, but the challenge is that there is little design and implementation of context-appropriate instruments and incentives. One critical foundation is network alignment – that innovation policy should be aligned with the goals and strategies of government departments responsible for promoting inclusive development (Von Tunzelmann, N, 2007. Approaching network alignment. Draft Paper for the U-Know Consortium: Understanding the relationship between knowledge and competitiveness in the enlarging European Union). The paper contributes by using qualitative analysis software to analyse the nature of shared policy goals and instruments in South Africa, and assess how these can be aligned with each other and with the goals of IID. Three main spaces for policy intervention are identified, to promote IID in a way that goes beyond the aspirational and the rhetorical. Such analysis of formal policy does not take into account the political will, capabilities and resources for implementation, but it does provide a systematic evidence base to effect strategic change.

1. Introduction

In the context of a global economic crisis and looming ecological disaster, with complex national political contestations around deepening poverty, inequality and unemployment, and a growing voice of those who have not benefited from transformation, the space is favourable in South Africa for prioritising the goals of innovation for inclusive and sustainable development. The strategic policy task since 1994, with the advent of a democratic government, has been to orient science, technology and innovation (STI) to industrial innovation and global competitiveness, but equally, to inclusive economic growth and inclusive socio-economic development, to ‘improve the quality of life for all’ (DST, Citation1996:19). The developmental thrust has been articulated over the past 20 years variously, in terms of a mission for technology for poverty reduction, and strategies for indigenous knowledge, social innovation, and human and social dynamics of innovation. However, an OECD critique of the national system of innovation in 2007 found that the mission of technology for poverty reduction had been neglected, largely in favour of mainstream research and development (R&D), innovation and big science (OECD, Citation2007).

Currently, the Department of Science and Technology (DST) is drafting a strategy to promote innovation for inclusive development (IID). The DST stands out globally in this deliberate attempt by government to design STI policy interventions that can contribute to shift structural inequalities. The draft strategy defines IID as:

Innovation that addresses the triple challenge of inequality, poverty and unemployment and enables all sectors of society, particularly the marginalised poor, informal sector actors and indigenous knowledge holders to participate in creating and actualizing innovation opportunities as well as equitably sharing in the benefits of development. (DST, Citation2016:11)

The challenge has been that while all government departments may share the policy goals and objectives of inclusion, there has been little design and implementation of new, context-appropriate instruments and incentives to achieve these goals across the system. We propose that the increasingly recognised value of ‘joined up’ governance (Klievink & Janssen, Citation2009) – policy activity that is integrated and coordinated not only across government but also with other actors in civil society or the private sector – is particularly critical in relation to IID. A focus on inclusive development of necessity involves the policies of a range of government departments responsible for improving well-being – water, sanitation and energy, for example – and on enhancing inclusive economic growth – policy oriented to the livelihoods of small-scale farmers, small, medium and micro-enterprises (SMMEs), cooperatives, and the informal sector. Thus, one critical foundation for an effective IID strategy is network alignment – that STI policy should be aligned with the goals, objectives and strategies of cognate departments (Von Tunzelmann, Citation2007).

The challenge for STI policymakers is to map these policy networks and identify where there can be stronger alignment. What is already in place that can support a refined vision of an inclusive NSI? What is in place to promote inclusive development, which can be adjusted or extended to mobilise STI more effectively? Where can policy be coordinated more effectively between departments to greater impact? How can existing mechanisms for coordination be recruited in support of the new strategy? Where are policy gaps that require new instruments? The contribution of this paper is to propose a framework and methodology that enable policymakers to address such questions.

The paper draws on a study conducted on behalf of the DST to identify and map out policy instruments related to IID across government departments, to assess policy readiness (Petersen et al., Citation2016). The main research objective here is to analyse the nature of, and alignment between, intended goals and instruments enshrined in the ‘innovation policy system’ across selected government departments. This is but a first step towards identifying spaces for stronger policy coherence and alignment in practice.

A conceptual framework to evaluate policy in terms of IID criteria, and a methodology for policy review using qualitative analysis software tools to map shared policy objectives, goals and instruments, were designed. The methodology proposed is a novel approach to the review of policy. It aims to address a common challenge in policy analysis: how to analyse ‘massive collections’ of policy text (Grimmer & Stewart, Citation2013:268).

The paper is organised in four sections. The first section reviews the literature on IID broadly defined, and on the innovation systems approach to policy, to articulate a conceptual framework. The second section describes the design of a novel methodology for policy analysis using NVivo software. The third section describes the main trends and patterns mapped out through the analysis, and the final section builds on this to identify modalities and spaces for intervention that could strengthen coherence, coordination and collaboration across government. We argue that improved alignment can contribute to improved implementation, thus going beyond the aspirational and the desirable.

2. Assessing IID policy goals and objectives: a framework

A necessary starting point for the research was to articulate a set of criteria for the assessment of policy texts as conducive to promoting and supporting IID. In this section, we examine the need to situate such criteria, first, within an emergent and evolving area of research, and second, within a policy terrain with little proven precedent. We then identify a set of criteria based on a transformative IID approach, which offers a framework for critically interrogating policy texts across government.

2.1. Defining IID

The emergent literature on IID is conceptually still very messy, reflected in the use of a range of terms, definitions and approaches (George et al., Citation2012; Johnson & Andersen, Citation2012; Bortagaray & Gras, Citation2014). Dutrénit (Citation2015) points out that while there is general agreement that we need to connect innovation to social inclusion, different approaches are distinguished by who each proposes to include, how and to what end – each with diverse implications for policy and practice. One review (Pansera, Citation2015) usefully argues that although it is difficult to categorise neatly the differing perspectives emerging in the literatures on inclusive growth, development and innovation, three competing notions of development are evident: business as usual (typical in bottom of the pyramid approaches such as Prahalad, Citation2005), reform (OECD, Citation2015), and transformation, the latter comprising a very small group of studies that question prevailing models (Fressoli et al., Citation2011). An important feature of the transformation ‘strand’ is a paradigm shift to promote innovation for, by and with marginalised people, whereas the other two approaches tend to emphasise the promotion of innovation for marginalised people (i.e. as consumers rather than producers and co-creators).

Studies in this ‘transformation’ strand have in common that they experiment with and explore the boundaries of innovation system concepts in relation to the prevailing issues of exclusion, marginalisation and inequality in low-income or highly unequal middle-income economies (Crespi & Dutrenit, Citation2014; Swaans et al., Citation2014). Hence, there is a move to align the insights of innovation studies with those of development studies. In turn, the value of an innovation systems approach with its emphasis on actors, interaction and learning is increasingly recognised by some scholars in development studies, particularly in relation to agricultural innovation and rural livelihoods (Sanginga et al., Citation2012; Nyamwena-Mukonza, Citation2013).

We situated our research within this strand of the literature, centred on the concept of innovation for inclusive development (IID) (Natera & Pansera, Citation2013; Joseph, Citation2014). IID broadly defined is ‘innovation that aims to reduce poverty and enable as many groups of people, especially the poor and marginalised, to participate in decision-making, create and actualise opportunities, and share the benefits of development’ (IDRC, Citation2011). As opposed to the sole emphasis on formal R&D and large firms, an IID approach also prioritises improving the welfare of low-income and marginalised consumers; prioritises improving the productivity of informal producers; and emphasises economic and social development (Heeks et al., Citation2013).

2.2. An emergent focus on policy systems

The late 1990s and 2000s witnessed a transformation in STI policy agendas from a linear understanding of the innovation process, to an ‘innovation policy paradigm’, emphasising learning, interaction and collective action, drawing on an innovation systems perspective (Lundvall & Borrás, Citation2005; Chaminade & Edquist, Citation2006, Citation2010; Von Tunzelmann, Citation2010; Borrás, Citation2011). This paradigm emphasises the link between innovation policy and cognate policies, such as industrial policy, or policies to promote SMMEs.

We are currently witnessing another transformation, a shift to consider how innovation policy can play a role in linking innovation to social inclusion (see OECD, Citation2015). There is, however, little policy precedent globally, given that IID has become part of experimental processes in only a few countries in the global South (Bortagaray & Gras, Citation2014). But there is general consensus that countries in the global South need to avoid mimetic and imitative practices, in adopting and using policy and analytical concepts designed in highly developed economies (Lastres et al., Citation2016).

The need to redesign conventional STI policy to take into account key contextual features, such as a large informal sector, is becoming a core theme of the emerging IID literature. As Kraemer-Mbula (Citation2015:6) critiques the typical trend:

Policy approaches to the informal economy do not explicitly refer to innovation. The ways in which government policies engage with the informal economy are rarely designed with a view to fostering innovation in this area.

An important lesson in the emerging literature is that orienting STI policy to IID requires a systemic approach, one that can account for complexity and that places the poor, and marginalised individuals and communities at the centre (Aguirre-Bastos et al., Citation2015). Moreover, in developing and emerging middle-income economies, facilitation, coordination and alignment are even more significant, for as Goedhuys et al. (Citation2015:85) caution, innovation policy in these contexts needs to be

… multi-faceted and complex, involving aspects of education policy, industrial policy, international trade policy, and various other institutional reforms. … Good coordination between ministries and between the private and the government sectors is therefore essential.

2.3. How do we analyse the enabling policy environment for innovation and inclusion?

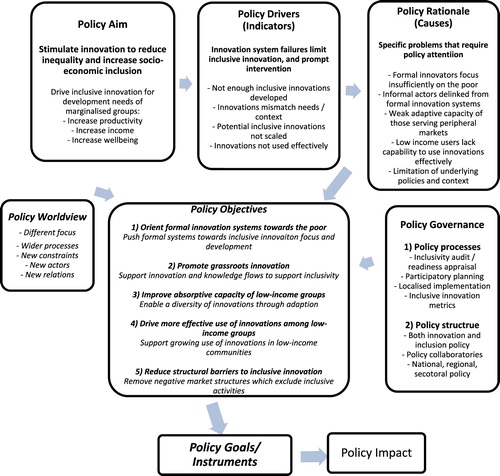

In order to define what transformative IID policy goals would look like, we draw on a framework developed by Foster & Heeks (Citation2015), summarised in , starting with the policy aim to ‘stimulate innovation to reduce inequality and increase socio-economic inclusion’. They first clarify the typical policy drivers and causes of an NSI’s failure to deliver inclusive innovation in a specific context, in order to inform the rationale for a government’s policy intervention and role (see the two boxes on the top right hand side). They identify five main causes of system failure (policy rationale), many of which are evident in South Africa. Take the problem that formal innovators focus insufficiently on the needs of the poor. In South Africa, formal innovators, in universities or public research institutes, tend to focus primarily on partners in the private sector, driven by financial imperatives, and by policy instruments to promote networks between public research systems and industry. Here is a problem of misalignment arising from policy instruments that do not promote inclusive development for the system as a whole. Another driver relates to knowledge diffusion failures: that low-income users lack capabilities to use innovations effectively. There is evidence of excellent low-cost innovations to solve water or health or energy problems, which are not well diffused and have little uptake. Here, misalignment arises because of the limited extent to which informal sector actors are included in the network, as economic agents. We thus conclude that the policy drivers and rationales identified by Foster & Heeks (Citation2015) provide a good start to frame an analysis of government goals and policy frameworks in South Africa.

Figure 1. Framework for analysing the policy environment. Source: Foster & Heeks (Citation2015).

Their framework offers a set of criteria useful for analytical purposes. First, is the need to distinguish policy worldviews, policy objectives, policy goals and specific instruments, and their alignment with each other and the goals of IID. Given that we are studying policy intent, we can focus on these dimensions only. To evaluate how policy governance or impact promote IID would require in-depth and extensive empirical research. Second, of particular value is the identification of five IID policy objectives (middle box) that can inform evaluation of specific goals and instruments. We adopted these analytic distinctions to inform data gathering and empirical analysis of South African policy documents (italics in ).

In sum, the framework proposes that to address inequalities and support socio-economic development, the innovation policy system needs to be reoriented to:

promote social inclusion;

encourage the participation of a new set of actors, including informal actors (such as grassroots innovators) and new formal actors (such as small, medium and micro-enterprises – SMMEs);

facilitate wider innovation processes to focus on the whole innovation cycle, for example, adapting business models and improving diffusion processes (Foster & Heeks, Citation2015).

3. Design and methodology

The research task was simple: to gather data and analyse alignment between the policy worldviews, objectives, goals and instruments evident in the policy texts of selected key government actors, in terms of how they promote IID, and in terms of alignment with national goals for socio-economic inclusion. Three specific research questions were addressed sequentially:

What is the nature of shared goals and instruments in current policy?

How are these goals and instruments mis/aligned with each other, and with the goals of IID?

What are the spaces for improved policy alignment?

The empirical focus was on national policies promoting livelihoods in informal settings, whether urban or rural. Although policies at the regional and local levels are critical for an IID strategy, we focused on the national level due to time and budget constraints. Following Foster & Heeks (Citation2015), we categorised government policies into three broad types: (1) contextual policy, (2) policy promoting socio-economic inclusion, and (3) innovation policy. In South Africa, contextual policy for inclusive development is set by the Presidency, Treasury, and departments of Economic Development (EDD), Trade and Industry (dti), and Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF). Policies that promote socio-economic inclusion are set by the departments of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR), Small Business Development (DSBD), and Water and Sanitation (DWS), amongst others. Innovation policy is the responsibility of the DST.

We conducted internet searches to identify 83 relevant policy documents promoting innovation and/or socio-economic inclusion, targeting informal sector actors,Footnote1 across the nine departments, up until 2015. As a starting point, we consulted the South African government website (www.gov.za), which provides a descriptive overview of the goals, strategies and mechanisms of each department. This was complemented by further in-depth investigation on each department or entity’s website, and consultation with government representatives at a seminar where the research report was presented (Petersen et al., Citation2016). Our key contact person at the DST was also asked to review the list of policy documents gathered.

Mapping the potential IID synergies, duplication and gaps across the 83 documents and 300 plus policy instruments identified from these documents is an extremely complex task. Our research contributes a new methodology for policy review, by creating searchable Excel and MS Access databases that could be used by researchers and policymakers. In order to provide a sound evidence base, we used NVivo software for qualitative data analysis, to extract themes and build higher-order analysis systematically. Our thematic analysis proceeded both from what emerged from the policy texts reviewed, and from what we know about IID normatively, drawing on the set of five policy objectives set out in above.

The first step of the procedure was to read and review each policy document, drawing out and listing key words and terms used in the text, in relation to each key dimension identified (see Appendix). For example, what does the text propose in terms of innovation and inclusion? The result of this process was captured in a MS Access database, and provided the ‘raw data’ for the policy review. Secondly, we used the tools of NVivo to organise, categorise and analyse the main policy thrusts of each department in relation to key themes and IID goals.

With the use of NVivo, we free coded the policy goals articulated, keeping close to the descriptions in the policy texts. We then adapted the five substantive IID policy objectives identified in as the basis to group and recode sets of categories that emerged from this first level of coding. How do the categories that emerged from our review reflect principles and practices of IID? For example, Foster & Heeks (Citation2015) propose that IID policy should orient formal innovation systems towards the poor, and they identify key dimensions for this task, such as linking informal actors into the formal system. We worked through our database descriptions, and found the intention to link in specific groups present in the text. However, we found that the policy texts include a distinction between the intent to link groups (1) to promote socio-economic inclusion, or (2) to promote innovation, or (3) to promote IID. We thus incorporated this threefold set of distinctions into our analytical categories. provides the list of contextualised categories of policy goals in relation to the five generic IID policy objectives, as derived through the coding process. The analysis of the 300 policy instruments was then linked to these IID-aligned policy objectives and goals, by recoding each text, thus creating a second database categorised in terms of the IID analytical distinctions in .

Table 1. Coding policy objectives and goals in terms of IID.

With the use of NVivo, we employed common content analysis techniques to analyse the data: word frequency and text search queries as well as descriptive statistics (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005; Grimmer & Stewart, Citation2013). While these techniques are very useful for analysing mounds of policy data, they also have limitations in adequately capturing meaning, for example. To address limitations associated with computer-assisted analysis of text, care was taken to read into the broader context of key words and terms and policy instruments, and to link the text to the broader socio-economic and political context. We also conducted historical analyses and in-depth research on key focus areas. (See Petersen et al., Citation2016, for a more detailed account of the methodology and analyses conducted.)

4. Alignment of current government policies with the DST’s goal to promote IID

This section draws on the databases to describe how current policy aims to orient the institutional environment in South Africa to promote and support innovation and socio-economic inclusion. On this basis, we can identify ways in which current policies and collaborative arrangements should be adjusted or extended to support a reorientation to an IID agenda, the task of the final section.

We first examine the nature of shared policy worldviews and policy objectives in the current policy networks, and consider how they are aligned across, or differ between, government departments. Secondly, we consider how policy goals and instruments are aligned with the objectives of IID. We do so by analysing only one IID objective, by way of illustration: how the existing policy goals and instruments of diverse government actors propose to reorient formal systems to promote innovation by informal actors at the grassroots.

4.1. What is the shared policy worldview related to innovation and socio-economic inclusion?

To provide an overarching perspective of the South African policy worldview (), we first analysed the key terms used by the nine departments in defining ‘innovation’, ‘socio-economic inclusion’ and ‘development’. Secondly, we identified the specific social groups targeted. We investigated whether marginalised social groups and informal sector actors were targeted. Thirdly, we analysed the type of socio-economic inclusion promoted, assessing the relative focus on improving well-being, income and livelihoods. We conducted word frequency queries to identify the strongest tendencies, and text search queries to identify the ideas typically connected to a key term, to illuminate their definitions.

4.1.1. How do the definitions of innovation, socio-economic inclusion and development reflect shared policy networks?

We identified the words and terms most frequently used in current policy texts for defining both ‘innovation and development’ and ‘socio-economic inclusion and development’. The most frequently used words across all departments are economic, development and innovative, reflecting a strong shared policy orientation.

To further explore how policy worldviews are articulated in the policy texts, we used text query searches to analyse the various usages of key terms. For example, a text search query of how the term innovation is defined across the government departments shows an emphasis on economic growth/development and formal technological processes, with emergent strands in relation to inclusion (using terms such as indigenous knowledge, appropriate technology, partnerships). Similarly, inspection of the phrases linked to the term ‘development’ showed that most policy documents are oriented to promote economic growth and industrial development in formal sectors and institutions.

We then compared the main objectives in those policies categorised as primarily promoting ‘innovation and development’ and those promoting ‘socio-economic inclusion and development’ (see ). Some actors promote both policy objectives almost equally, but on a small scale: Treasury and DSBD. Echoing the aggregated analysis, the policies promoting ‘socio-economic inclusion and development’ focused on economic, water and development. This focus is emphasised most strongly by DAFF, the Presidency, DRDLR, DWS, and the dti, in descending order. While ‘innovation and development’ is most strongly promoted by the DST, the EDD, Treasury and DSBD share these objectives on a smaller scale. Alongside innovation, these policy texts use the words economic, technology, social, development, and then inclusion, growth, life and services most frequently.

Figure 2. Word clouds on the key objectives for ‘innovation and development’ and ‘socio-economic inclusion and development’.

Development for these policy actors is defined in a broad ranging and comprehensive manner, including social cohesion, equity through redress, health, human settlements and rural development, industrial and scientific development, productivity, economic growth, and spatial and inclusive development.Footnote2 This suggests the presence of linkages across innovation and social policies, an important condition for an effective IID strategy (Cassiolato et al., Citation2008).

Using such techniques, it was possible to identify a set of policy texts with shared policy goals around innovation and development, which represent critical starting points across government for promoting a new IID strategy.

4.1.2. Who are the main social groups targeted in policy?

The main social groups targeted for inclusion are commonly identified as youth, rural communities, disadvantaged persons, farmers, black persons and small enterprises, in that order. These reflect socio-political challenges in the South African context – inequalities related to race, gender and spatial location, and high levels of youth unemployment. The target groups reflect the interconnected focus on livelihoods and inclusion. It is thus not sufficient to define target groups solely in terms of their economic roles as informal actors, or as ‘the poor’ or ‘the marginalised’, in the South African context.

If the DST wants to promote IID policy objectives, where are the policy objectives of other departments most closely oriented to the benefit of relevant target groups? At the level of national developmental goals, we found that the Presidency’s policy objectives are very strongly oriented to youth and schools, women and people with disabilities. Redress targets to address the needs of these marginalised groups have been cascaded down to all government departments, informing the way they orient their strategies and performance measures. The objectives of Treasury, in line with its mandate, are most specifically oriented to banks, communities and cooperatives. A key issue for future research is to assess the extent to which the policy instruments to achieve these goals are implemented.

We can discern three sets of target groups from the departments that promote a focus on ‘inclusion and development’ more strongly (DAFF, DRDLR, DWS, the dti). DAFF and DRDLR focus unequivocally on farmers and other actors in rural areas, including women, and small producers. DRDLR prioritises black farmers, commercial farmers and land reform more strongly than DAFF. The dti focuses on black owned enterprises for the disadvantaged, as well as women and youth. Finally, DWS prioritises expanding access to water for productive use, with a focus on: poor water users, farmers, women, informal actors and equity.

Three departments promote ‘innovation and development’ more strongly (DST, EDD and DSBD). EDD and DSBD target similar groups, defined by historical disadvantage and marginalisation, as well as informal economic actors: black and poor persons/communities, youth, black women, those with disabilities, and small enterprises and cooperatives. The DST targets the full spread of groups prioritised in national goals of equity and redress: communities, rural, disadvantaged, SMMEs, women, citizens, formal groups, as well as indigenous communities and informal groups (such as grassroots innovators).

4.1.3. What type of socio-economic inclusion is promoted?

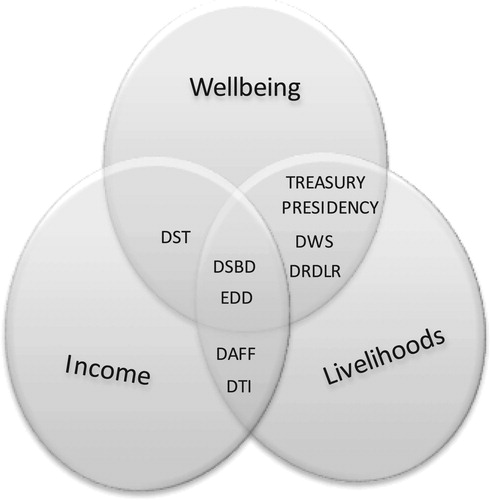

Foster & Heeks (Citation2015) distinguish three broad IID outcomes: to improve well-being/income/livelihoods. Our analysisFootnote3 of the type of socio-economic inclusion articulated in the policy texts shows that the greatest priority is accorded to livelihood activity: livelihoods, economic, income, water and well-being are the most frequently used terms. We investigated key ways in which government actors propose to improve livelihoods, and uncovered a strong policy focus on job creation and employment opportunities. The objectives in relation to improved income are strongly interrelated with improved well-being and livelihoods: there is a focus on improving livelihoods, small business, skills development, youth, broad-based black economic development and employment creating activities. Likewise, the focus on well-being is interrelated, but with a stronger focus on inclusion, access and social cohesion.

We conclude that all government departments aspire to this set of IID policy outcomes in some way, but that the emphasis falls more strongly on promoting socio-economic inclusion, rather than innovation.

uses a Venn diagram to depict these three intersecting outcomes, positioning each department in terms of the number of policy documents related to each. Although all of the departments prioritised improving livelihoods, income and well-being to some extent, each tended to place greater emphasis on one or two of these outcomes. For each department, we thus identified the two IID objectives prioritised most strongly. We found that while most of the government departments aim to improve livelihoods and income, or livelihoods and well-being, the DST’s current policy instruments are more strongly focused on improving income and well-being.

Figure 3. Venn diagram illustrating the main intersecting objectives of improved well-being, income and livelihoods, by department.

Our analysis thus points to a potential gap in promoting the use of innovation for improving livelihoods. We explore this further through an analysis of policy instruments to promote grassroots innovation, which articulate more specific and targeted strategic objectives.

4.2. How do current policy goals and instruments promote grassroots innovation?

The issue of grassroots innovation, and the indigenous knowledge (IK) and agency of informal actors, is critical to IID. As we may expect, the policy goals and mechanisms to promote innovation by informal actors are limited at this stage, but there are important emergent trends, which we explore in this section.

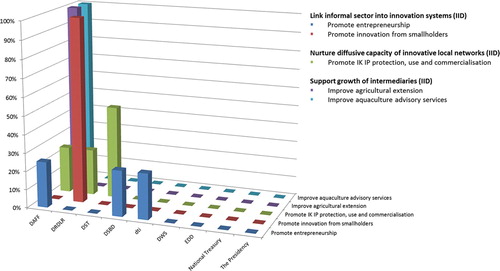

We categorised the existing policy instruments in terms of three broad IID policy goals for grassroots innovation, as defined by Foster and Heeks (Citation2015) (). Not all departments are involved, and of note, the focus is primarily on agricultural-oriented innovation: improving agricultural extension services and aquaculture advisory services are most common, followed by promoting innovation from small-holders, and promoting IK intellectual property (IP) protection, use and commercialisation, and finally, promoting entrepreneurship.

Figure 4. Proportion of policy instruments potentially significant for promoting grassroots innovation, by department.

depicts the policy instruments associated with each of these three grassroots innovation IID goals, for each department.

In terms of the goal of linking informal grassroots actors into innovation systems, we find existing policy instruments to promote entrepreneurship and innovation from small-holders. The dti and DSBD are potential partners for the DST in promoting entrepreneurship for grassroots innovation. Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA) plays a key role, implementing a Basic Entrepreneurial Skills programme in partnership with Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). DAFF promotes entrepreneurship through providing support programmes to SMME agro-processors, in collaboration with entrepreneurial training agencies. The Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) funds new entrepreneurs, but its focus has been on the formal sector and larger enterprises, and may need to be extended to informal actors. Through these instruments, DAFF, dti, SEDA and DSBD are important potential partners to promote grassroots innovation and entrepreneurship.

DRDLR, particularly its Rural Infrastructure Development (RID) branch, is the only actor potentially focused on grassroots innovation by small-holders. Here is a gap for future DST collaboration. The RID branch provides ICT and economic infrastructure development services, and access to funding. The chief directorate, Technology Research and Development aims to develop and adapt innovative and appropriate technologies, to contribute to poverty eradication through promoting Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS), research and technology, and environment and natural resource utilisation. Its AgriParks programme extends the idea of an incubator to set up industrial parks to enable the development of rural enterprises and industries. The design involves an inclusive and collaborative process and focuses on developing opportunities for small- and medium-scale farmers.

In terms of the goal of nurturing diffusive capacity of innovative local networks, existing DST instruments promote an institutional framework for intellectual property protection, use and commercialisation of IK. To explore IK related policy further, we extracted a word tree of the term ‘indigenous’. We found that the term is used by the DST through National Advisory Council on Innovation and Technology Innovation Agency, as well as DAFF and DWS. In this way, we could identify potential gaps and degree of alignment between departments. One strand refers to indigenous knowledge and technology, another to indigenous and local communities, and a third to governance and insertion into the formal innovation system. In the Agricultural Policy Action Plan, DAFF articulates the goal of identifying innovations by farmers, but we could not locate a specific instrument to give effect to this goal. An instrument to promote grassroots innovation and IK by farmers is a potential gap for DST alignment.

The third goal, of promoting the growth of intermediaries to support grassroots innovators, primarily emphasises improving agricultural extension and aquacultural advisory services. Extension services are important as a policy instrument to diffuse innovation in relation to small-holder farmers. Three additional features stand out in relation to grassroots innovation specifically: the potential role of the new local Agriculture Development Centres; enhancing the agency and capacity of farmers through the use of logbooks to hold extension officers accountable; and building links between actors at provincial and local levels.

The analysis in this section shows that to promote grassroots innovation by rural farmers and informal actors, there are existing instruments that can be deepened and extended, through coordination with an IID strategy. However, there also are noticeable gaps that will need to be addressed: grassroots innovation is currently not oriented to include informal actors in micro-enterprises, or to address the specific needs of unemployed women or youth in urban areas and informal settlements. Future research could explore the extent to which the DST’s Grassroots Innovation Programme, which was piloted in 2016, addresses these gaps in practice.

5. What are the spaces for policy alignment?

From the analysis, we extract three main modalities for strategic policy intervention to promote IID:

Coordinate across the nine departments to extend, deepen and align the focus of existing policy instruments to

integrate innovation goals where they are missing, or

promote socio-economic inclusion goals where the emphasis is solely on formal innovation goals.

Design new policy instruments to address significant gaps in existing policy instruments.

Facilitate the formation of effective implementation networks.

in the Appendix includes a detailed list of areas where policy could be extended and aligned, and where new policy instruments may be needed. In this section, we provide specific examples of each, based on our in-depth analysis of the policy data related to grassroots innovation.

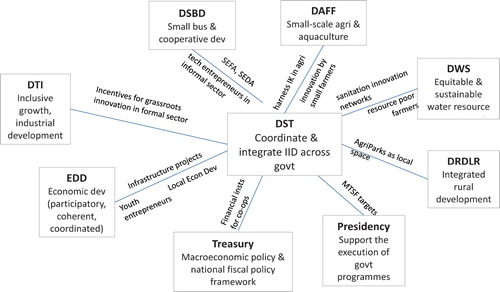

proposes a policy network that can be coordinated around grassroots innovation. We identify specific spaces for policy intervention (each strategy is identified on the line between the DST and the lead government department). For example, DAFF’s strategies do not include a focus on the indigenous and local knowledges of farmers in the informal sector, a gap that the DST can address by extending and aligning its own Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) strategy. DRDLR has a strategy to build AgriParks to stimulate agro-processing at the local level, but does not include goals and mechanisms to stimulate grassroots innovation, a potential space for DST intervention. The DST can link with and introduce innovation policy targeted to the informal sector into DSBD’s National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy (NIBUS) programme to uplift informal businesses; and it can partner with DWS, EDD and DSBD to support the creation of livelihood opportunities in relation to the provision of water and sanitation services. The DST could also work with Treasury, DSBD and EDD to ensure that funding instruments targeted at informal actors, and marginalised people generally, do not specify requirements that may preclude their participation (e.g. formal business plans and complicated application forms). Participation by municipalities, traditional authorities, community organisations and local leadership may lead to greater impact and realisation of inclusive development goals.

Figure 5. Spaces to deepen and extend policy alignment to promote grassroots innovation, towards IID.

The DST also has gaps in its own array of instruments, which are oriented more strongly to formal institutions – for example, there is a need to create mechanisms to review, incentivise and support formal science, engineering, technology and innovation institutions (SETIs) to extend their knowledge to engage with the needs and knowledge of informal and marginalised actors.

A major challenge is to identify mechanisms to orchestrate effective development networks. Diffusing and implementing an IID strategy requires the political will to reprioritise and change existing policy. The danger is that policy actors may formally appear to support IID goals, while carrying on with ‘business as usual’, on the ground and in their practice.

6. Good policy intent, but the challenge remains implementation

In this paper, we argue that orienting the national system of innovation more effectively to ‘increase well-being and expand prosperity for all in South Africa’ DST (Citation2016:1), particularly those marginalised and in informal settings, or in the informal sector, requires a different policy worldview and set of policy goals and instruments, and involves a wider set of actors and processes.

The paper contributes a set of conceptual distinctions to analyse what policy objectives, goals and instruments ‘count’ as promoting IID. Using this framework, the analysis suggests that while policy worldviews and goals may be shared at the highest level, when it comes to strategies, programmes and instruments, there are significant differences between government departments. The emphasis falls most strongly on the goals of socio-economic inclusion, and the DST operates largely in isolation in addressing goals of innovation, with even less emphasis on IID. Innovation policy needs to promote socio-economic inclusion more strongly, and to address the lack of IID instruments oriented to improve livelihoods; but equally, innovation needs to be inserted more strongly into policies to promote socio-economic development and inclusion. Using grassroots innovation as an example, this paper highlights specific spaces for policy intervention, indicating where policy could be extended and deepened to better align with IID objectives, and where new policy instruments are needed.

Since the analysis of policy documents can only indicate government’s strategic intent, it does not take into account the political will to enact, nor the capabilities and resources to implement, policy instruments effectively and efficiently. However, it does provide a systematic evidence base to drive strategic change. The systemic analysis of policy texts points to spaces for alignment and collaboration towards a coordinated innovation policy system that can support an IID agenda.

Finally, the paper contributes a methodology for systematic reviews of policy that can be adopted in other focus areas. Like Grimmer & Stewart (Citation2013), who point out the value of content analysis (including word frequency analysis) and the usefulness and limitations of computer-assisted analysis, we argue that our rigorous methodology provides an advance on current research practice. It lays a solid foundation for analysing how IID is reflected in policy implementation and practice, which should be the focus of future research.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of two external reviewers of the full research report, Isabel Bortagaray and Susan Cozzens. Their intellectual contributions to enhance the conceptual rigour of the research have been invaluable. Lastly, we acknowledge the team of researchers, Jennifer Rust, Azinga Tele and Andrea Juan, who participated in the data-gathering and analysis process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term ‘informal sector actors’ is used as a shorthand to refer to individuals or groups operating at the intersection between marginalised households and communities. In South Africa informal actors are characterised by exclusion and marginalisation along gender, race, class, education levels and spatial grounds. Some examples in South Africa include: informal sector enterprises such as township and rural enterprises; new formal sector enterprises such as SMMEs (particularly micro-enterprises) and cooperatives; survivalist enterprises, that is, micro-enterprises aimed at subsistence and generating an income below the poverty line; subsistence farmers; emerging farmers in aquaculture, a priority sector in South Africa; small-scale miners, a priority sector in South Africa; innovators (inventors) in the informal sector; and indigenous knowledge holders.

2 This analysis is based on a word tree of the term development for the sub-set of actors that promote the policy objectives of ‘innovation and development’.

3 The analysis in this section focuses on the strategic objectives related to the type of socio-economic inclusion prioritised. We coded the objectives articulated in the policy texts, and analysed the frequency of key related terms across all policy texts.

References

- Aguirre-Bastos, C, Bortagaray, I & Weber, KM, 2015. Inclusive policies for inclusive innovation in developing countries: The role of future oriented analysis. Paper presented at the 13th Globelics International Conference, 23-25 September, Havana, Cuba.

- Borrás, S, 2011. Policy learning and organizational capacities in innovation policies. Science and Public Policy 38(9), 725–34. doi: 10.3152/030234211X13070021633323

- Bortagaray, I & Gras, N, 2014. Science, technology and innovation policies for inclusive development: Shifting trends in South America. In Crespi, G & Dutrenit, G (Eds), Science, technology and innovation policies for development. The Latin American experience. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Bortagaray, I & Ordóñez-Matamoros, G, 2012. Introduction to the special issue of the review of policy research: Innovation, innovation policy, and social inclusion in developing countries. Review of Policy Research 29(6), 669–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2012.00587.x

- Cassiolato, J, Soares, M & Lastres, H, 2008. Innovation in unequal societies: How can it contribute to improve inequality? Paper presented at the International Seminar on Science, Technology, Innovation and Social Inclusion, May 2008, UNESCO, Montevideo.

- Chaminade, C & Edquist, C, 2006. From theory to practice. The use of the systems of innovation approach in innovation policy. In Hage, J & Meeus, M (Eds.), Innovation, science and institutional change. A research handbook. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Chaminade, C & Edquist, C, 2010. Rationales for public policy intervention in the innovation process: A systems of innovation approach. In Kuhlman, S, Shapira, P, & Smits, R (Eds.), Innovation policy – theory and practice. An international handbook. Edward Elgar Publishers, London.

- Cozzens, S & Sutz, J, 2014. Innovation in informal settings: Reflections and proposals for a research agenda. Innovation and Development 4(1), 5–31. doi: 10.1080/2157930X.2013.876803

- Crespi, G & Dutrenit, G (Eds), 2014. Science, technology and innovation policies for development: The Latin American experience. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland.

- DST (Department of Science and Technology), 1996. White Paper on Science and Technology. DST, Pretoria.

- DST (Department of Science and Technology), 2016. Draft innovation for inclusive development strategy. DST, Pretoria.

- Dutrénit, G, 2015. Innovation for inclusive development: the challenge for STI policies. Presentation at the HSRC Annual Innovation and Development Lecture, 1 July, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Foster, C & Heeks, R, 2015. Policies to support inclusive innovation. Development Informatics, Working Paper 61, Centre for Development Informatics, University of Manchester, UK.

- Fressoli, M, Smith, A & Thomas, H, 2011. From appropriate to social technologies: Some enduring dilemmas in grassroots innovation movements for socially just futures. Paper presented at the Globelics International Conference, 15-17 November, Buenos Aires.

- George, G, McGahan, A & Prabhu, J, 2012. Innovation for inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. Journal of Management Studies 49(4), 661–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01048.x

- Goedhuys, M, Hollanders, H & Mohnen, P, 2015. Innovation policies for development. In Doutta, S, Lanvin, B & Wunsch-Vincent, S (Eds), The Global Innovation Index 2015 2015. Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO, Fontainebleau, Ithaca, and Geneva.

- Grimmer, J & Stewart, BM, 2013. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis 21, 267–97. doi: 10.1093/pan/mps028

- Heeks, R, Amalia, M, Kintu, R & Shah, N, 2013. Inclusive innovation: Definition, conceptualisation and future research priorities. Development Informatics Working Paper 53, Centre for Development Informatics, University of Manchester, UK.

- Hsieh, H-F & Shannon, SE, 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15(9), 1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

- IDRC (International Development Research Centre), 2011. Innovation, informality and improved livelihoods. IID brochure. IDRC, Ottawa.

- Johnson, B & Dahl Andersen, A, 2012. Learning, innovation and inclusive development. New perspectives on economic development strategy and development aid. Aalborg University Press, Aalborg.

- Joseph, KJ, 2014. Exploring exclusion in innovation systems: Case of plantation agriculture in India. Innovation and Development 4(1), 73–90. doi: 10.1080/2157930X.2014.890352

- Klievink, B & Janssen, M, 2009. Realizing joined-up government—Dynamic capabilities and stage models for transformation. Government Information Quarterly 26, 275–84. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2008.12.007

- Kraemer-Mbula, E, 2015. Innovation policy approach for the informal economy: towards a new policy framework. Paper presented at the 13th Globelics International Conference, 23-25 September, Havana, Cuba.

- Lastres, H, Marcello, C & Walsey, 2016. Production and innovation systems and sustainable regional development: The experience of a Brazilian development bank. IndiaLICS conference, 16-18 March, Trivananthapuram.

- Lundvall, BÅ & Borrás, S, 2005. Science, technology and innovation policy. In Fagerberg, J, Mowery, DC & Nelson, RR (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Natera, JM & Pansera, M, 2013. How innovation systems and development theories complement each other. MPRA Paper. http://mpra.ub.unimuenchen.de/id/eprint/53633 Accessed 4 May 2015.

- Nyamwena-Mukonza, C, 2013. A conceptual framework for implementing sustainable livelihoods and innovation in biofuel production among smallholder farmers. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 5(3), 180–88. doi: 10.1080/20421338.2013.796750

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2015. Innovation policies for inclusive development: Scaling up inclusive innovations. OECD, Paris.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2007. Reviews of innovation policy: South Africa. OECD, Paris.

- Pansera, M, 2015. The cross-pollination of development and innovation discourses: an integrative literature review. Paper presented at the Globelics International Conference, 23-25 September, Havana, Cuba.

- Petersen, I, Kruss, G, Rust, J, Juan A & Tele, A, 2016. Is South Africa ready for ‘Innovation for Inclusive Development’? A review across national policy. Report to the DST prepared by the Education and Skills Development programme, Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria.

- Prahalad, C, 2005. The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: Eradicating poverty through profits. Wharton School Publishing, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Sanginga, P, Waters-Bayer, A, Kaaria, S, Njuki, J & Wettasinha, C, 2012. Innovation Africa: Enriching farmers’ livelihoods. Routledge, London.

- Swaans, K, Boogaard, B, Bendapudi, R, Taye, H, Hendrickx, S & Klerkx, L, 2014. Operationalizing inclusive innovation: Lessons from innovation platforms in livestock value chains in India and Mozambique. Innovation and Development 4(2), 239–57. doi: 10.1080/2157930X.2014.925246

- Von Tunzelmann, N, 2007. Approaching network alignment. Draft Paper for the U-Know Consortium: Understanding the relationship between knowledge and competitiveness in the enlarging European Union.

- Von Tunzelmann, N, 2010. Technology and technology policy in the post-war UK: ‘Market failure’ or ‘network failure’? Revue Déconomie Industrielle 129–130, 237–58. doi: 10.4000/rei.4157