ABSTRACT

Commercial farm workers in South Africa endured centuries of exploitation and abuse until the 1990s, when progressive legislation was promulgated that confers rights to workers aimed at improving their living and working conditions, including through a sector-specific statutory minimum wage. However, violations of labour rights are widespread in the agriculture sector, and farm workers are arguably more vulnerable than before as they face ongoing evictions, casualisation and exploitation. This research study, conducted among women farm workers in the Western Cape and Northern Cape provinces, documents labour rights violations in the areas of wages and contracts and occupational health and safety. Apart from farmers themselves, government is responsible for failing to enforce compliance with pro-worker legislation, while trade unions have failed to represent farm workers and hold farmers and government to account.

1. Introduction

The relationship between commercial farmers and farm workers in South Africa has been complex and multi-layered since its origins in ‘master-slave’ relations at the Cape of Good Hope in the seventeenth century (Waldman Citation1996; Williams Citation2016), but has always been characterised by power asymmetries that left workers vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Until relatively recently, this relationship was virtually unregulated. The geographical dispersion and isolation of farms, and the anomalous reality of commercial farms being closed spaces where employers and employees lived and worked side by side – albeit with very different qualities of life – may have created a pseudo-‘family’ (du Toit Citation1992; Atkinson Citation2007), but it also created a context ripe for violations of human rights that went unseen, unreported and unpunished. If the farm was, indeed, a ‘family’ it was a highly dysfunctional family.

After the transition to a democratic dispensation in 1994, progressive legislation was introduced that conferred economic, social, cultural, civil and political rights to all South Africans, including labour laws that regulated the relationship between employers and employees and aimed to protect workers against unfair labour practices. Employers in the agricultural sector are now required to issue written contracts to all farm workers, to pay an annually adjusted minimum wage, to provide protective clothing to workers who are exposed to pesticides, to allow workers to join trade unions and to allow labour inspectors to monitor working conditions on farms. However, this research will demonstrate that significant numbers of farmers and farm managers are not complying with these requirements.

This study aimed to understand the nature, extent and impacts of labour rights violations, as experienced by women farm workers in the Western Cape and Northern Cape provinces of South Africa. The findings confirm a pattern of systematic failures: by farmers to comply with labour legislation, by government to enforce this legislation, and by workers’ representatives – specifically, trade unions – to hold either farmers or government accountable. It should be noted that these findings are not unique to the Western Cape and Northern Cape. Violations of farm workers’ labour rights have been recorded in most provinces of South Africa, including Eastern Cape (Naidoo et al. Citation2007; Brandt & Ncapayi Citation2016), Free State (Visser & Ferrer Citation2015), Limpopo (Hall et al. Citation2013; Addison Citation2014) and North West (Lemke & Jansen van Rensburg Citation2014).

This ongoing exploitation and abuse of farm workers in South Africa must be contextualised, both historically and in relation to the raft of pro-worker legislation that was introduced after 1994. The next section of this paper provides a brief historical context. Then the research methodology is introduced, followed by a presentation of findings in three areas: contracts, wages and deductions; occupational health and safety; and labour rights on farms.

2. Historical context

Agricultural labour in the Western Cape dates back to the 1600s, when local Khoisan and imported slaves worked on farms owned by Dutch colonisers (Bernstein Citation1996). Abuse of farm workers was pervasive throughout the colonial period and the apartheid years, and included physical assaults, rape, child labour, inhumane living conditions, summary evictions of farm worker families, and the dop system.Footnote1 For more than three centuries, government policy favoured White commercial farmers at the expense of Black farmers, sharecroppers and farm workers (Van Onselen Citation1991; Pahle Citation2015). After the National Party came to power in 1948, decades of racially discriminatory legislation such as the ‘colour bar’, and an education system that invested heavily in White skills accumulation while reproducing an unskilled or semi-skilled Black workforce, created a highly distorted labour market and one of the world’s most unequal societies (Lipton Citation1986; Terreblanche Citation2002). Whites controlled most of South Africa’s land and capital, while rural Africans and ColouredsFootnote2 who had been systematically dispossessed of their land were either confined to under-resourced ‘homelands’ or employed as low-paid farm workers on heavily subsidised White-owned commercial farms (Hall & Cousins Citation2018).

Two forces have intervened in recent decades to modify the complex relationship between farmers and farm workers. The first is a protracted decline in agricultural employment in South Africa, exacerbated since the 1980s by agricultural deregulation and liberalisation (Van Zyl & Vink Citation1988; Hall Citation2009; Bernstein Citation2013). Employment in commercial agriculture peaked at around 1.8 million workers in the 1960s but fell to 650,000 by 2010 (BFAP Citation2012), while labour costs as a share of total costs halved, from close to 30% to less than 15% (Liebenberg & Pardey Citation2010). During this period, the real value added per agricultural worker doubled (Greyling et al. Citation2015). At the same time, a radical restructuring of agricultural labour relations was occurring to the detriment of farm workers, whose livelihood insecurity was compounded by a shift away from a permanent labour force living on farms towards hiring of seasonal and casual labourers. Almost three million people were forcibly evicted from farms and relocated to rural towns between 1950 and 2004 (Wegerif et al. Citation2005) from where they were re-employed as casual or seasonal farm workers, but on significantly worse terms and conditions than before. A study in Rawsonville, Western Cape found that two-thirds of residents of the informal settlement of Spooky Town were evicted farm workers (Women on Farms Project Citation2011).

The intersection of declining aggregate employment and accelerating casualisation of agricultural labour can be seen in farming areas such as the Hex River Valley, where total employment fell by 17% between 2007/08 and 2013/14, but the permanent workforce collapsed by 53% while the seasonal workforce increased by 38%, reflecting a near-reversal in the ratio of permanent to seasonal workers, from 61:39 to 35:65 (Visser & Ferrer Citation2015:138).

Agricultural restructuring has weakened the relationship between farmers and farm workers, with ambivalent consequences. On the one hand, evicted and casualised workers have lost the benefits of ‘racialised paternalism’ (Bolt Citation2017): permanent employment, accommodation on farms and a range of informally negotiated goods and services (e.g. food, transport). On the other hand, the almost total control that farmers previously exerted over workers living on their farms has been broken. Farm workers living off farms are freer to mobilise and campaign for their rights, with less fear of losing their jobs and homes. It is no coincidence that the strike of 2012/13 was instigated mainly by seasonal workers living in De Doorns and other towns. Many of the strike leaders were women rather than men, African rather than Coloured, living in rural towns rather than on farms, and seasonal rather than permanent workers, contra dominant representations of farm workers in the Western Cape (Eriksson Citation2017).

The second driver of radical changes in farmer-farm worker relations was the introduction by the African National Congress (ANC) government of legislation intended to protect the rights of workers, including regulations that explicitly targeted farm workers. The ANC’s constituency is dominated by Black South Africans, and it was elected with a mandate to reverse the historical legacy of institutionalised racism, oppression and exploitation by the White minority. Labour relations were a key site of contestation. Improvements were urgently needed in workers’ wages, bargaining power, health and safety at work, compensation for work-related injuries and social security benefits (Human Rights Watch Citation2011; Visser & Ferrer Citation2015). Building on South Africa’s progressive Constitution (Republic of South Africa Citation1996), relevant labour laws that were promulgated or amended include the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (Republic of South Africa Citation1997a), Labour Relations Act (Republic of South Africa Citation1995a), Occupational Health and Safety Act (Citation1993a), and Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (Citation1993b). In addition, the Unemployment Insurance Act (Republic of South Africa Citation2001) specifies benefits payable to workers during periods of unemployment.

In the agriculture sector, the Extension of Security of Tenure Act (Citation1997b) aimed to protect farm dwellers’ tenure security rights, and the Sectoral Determination for Farm Workers (Republic of South Africa Citation2006) extends specific rights and protections to farm workers. However, these progressive laws have been only partially or perfunctorily implemented. One reason is that interference in the labour market to regulate relations between employers and employees contradicts the ANC’s neoliberal economic stance, which favours market forces over state intervention and respects private property rights, even if that property was acquired illegitimately. This ideological position also explains why the ANC has been so slow and seemingly reluctant to implement meaningful land reform (land restitution, tenure reform and redistribution.) For example, the Extension of Security of Tenure Act has been used by farmers for the opposite purpose to its intention: ‘because the Act outlined procedures that land owners should follow in the event of an eviction, it facilitated rather than prevented evictions’ (Brandt & Ncapayi Citation2016: 225).

Ironically, through a combination of ‘the law of unintended consequences’ and a failure to effectively enforce these laws and regulations, farm workers have arguably been left more vulnerable than before. Moreover, recent policy changes have served the interests of commercial farmers rather than farm workers. For example, farmers can (and do) apply for exemption from paying legislated minimum wages, and the recently introduced national minimum wage (as of January 2019) is set at a higher rate than the Sectoral Determination wage for farm workers.

Some analysts argue that the new labour legislation, by imposing higher monetary and non-monetary costs on farmers, actually accelerated trends in farm worker evictions, casualisation and labour-substituting mechanisation (Sparrow et al. Citation2008; BFAP Citation2012). One empirical study estimated that farm workers’ wages increased by 17% but agricultural employment fell by 13%, following the introduction of the minimum wage for farm workers in 2003 (Bhorat et al. Citation2012). More recently, agricultural employment fell by 8.2% in one year after the minimum wage was raised by 52%, following the farm worker strike of 2012/13 (Ranchhod & Bassier Citation2017). However, even if labour costs have been rising, incomes of many commercial farmers have been rising even faster. Between 1996 and 2013, South African exports of fruit and vegetables more than doubled in real terms (Greyling et al. Citation2015), while wine exports increased by more than 500% (SAWIS Citation2014). The Western Cape benefited greatly from the lifting of economic sanctions that were imposed against the apartheid regime, and now produces more than 50% of South Africa’s agricultural exports.

Despite this strong growth in fruit and wine production, therefore, employment of workers in this sector is increasingly precarious. This research study focused on farm women because they are more likely than men to be ‘casualised’ – evicted and re-employed on a daily or seasonal basis, which is more insecure than male-dominated permanent employment (Roberts & Antrobus Citation2013). Women farm workers are often paid less than men (Naidoo et al. Citation2007), they are less likely to be given written contracts, housing on farms is almost always registered to men rather than women (Phuhlisani Citation2017), and pregnant women are routinely denied employment and are not paid maternity leave (Human Rights Watch Citation2011:29). Seasonal farm women are among the poorest, least visible and most vulnerable categories of workers in South Africa.

3. Methodology

This research study was commissioned by Women on Farms Project (WFP), a feminist NGO that works with women farm workers and farm dwellers in the Western Cape and Northern Cape provinces of South Africa, after it received numerous complaints from farm women about poor working conditions and violations of their labour rights. A mixed methods research design was devised for primary data collection, following a participatory approach in order to ensure inclusion and ownership of the research by women working on commercial farms. To start the process, 50 farm women from Western Cape and Northern Cape were brought together in Stellenbosch. The intention to undertake a research study on working conditions on farms was explained. Women brainstormed in plenary, small groups and pairs about labour rights violations they had either experienced personally or knew about: low wages, exposure to pesticides, no toilets in the vineyard, and so on. A facilitator then clustered the issues raised by the women into themes. This information was used to design the survey questionnaire, which was divided into three modules: contracts and wages, occupational health and safety, and broader labour rights.

Data collection was undertaken by 30 women farm workers known to WFP (15 from each province) who were trained as enumerators to administer the questionnaire, which was piloted and revised before fieldwork started. Each enumerator was paid for completing a specified number of questionnaires. They were instructed to visit farms in their home areas where WFP does not work, in their home areas, to avoid contamination or bias – the majority of farm workers are not associated with NGOs like WFP and are not unionised, so they have not been sensitised about their rights.

A total of 343 questionnaires were administered to a sample that was stratified by area and each worker’s employment status. In the Western Cape, which has a higher number of farm workers, 201 questionnaires (59%) were completed across six commercial farming areas: De Doorns, Paarl, Rawsonville, Stellenbosch, Wellington and Wolseley. In the Northern Cape 142 questionnaires were completed (41%) in four commercial farming areas: Augrabies, Kakamas, Keimoes and Upington. Roughly equal numbers of permanent workers (159 = 49%) and seasonal workers (168 = 51%) were interviewed. In addition, four focus group discussions were facilitated with groups of 8–12 women in the Northern Cape and Western Cape, which generated personal narratives to complement and give texture to the statistical survey analysis. All individual interviews and group discussions were conducted in Afrikaans and then transcribed verbatim and translated into English.

After data collection and preliminary analysis, another workshop was held in Stellenbosch with 30 farm women from each province who were neither enumerators nor interviewees, to validate the findings and deepen the preliminary analysis. The women discussed whether the findings reflected their reality and added their insights to interpret and contextualise the findings. This participatory process informed and enriched the final research report (Devereux et al. Citation2017) from which this paper draws.

For analysis purposes, data were disaggregated by two criteria – province and employment status – as well as by export or domestic market producers, to establish whether working conditions differ between provinces, between workers with permanent contracts and those employed as seasonal or daily labourers, and between workers employed on farms that produce for export (237 = 70%) or mainly for the South African market (102 = 30%). For each of these six analytical categories, the number of respondents exceeds 100, which allows fairly robust conclusions to be drawn. However, these findings are not generalisable to all farm workers in South Africa. Instead, they should be regarded as indicative of the labour conditions currently experienced by women working on commercial farms in the Western Cape and Northern Cape.

Another possible limitation of this research is response bias arising from fear of reprisals by farmers. Violations of labour rights is a sensitive topic, and although trust was established by recruiting women farm workers as enumerators, some respondents felt too intimidated to speak openly about their personal experiences.Footnote3 (‘I am too scared to talk’. ‘We have to pretend that everything is fine, otherwise you lose your job’.)Footnote4 Just as ‘confirmation bias’ presents an overly positive view of reality, the implication of this reticence among respondents is that labour conditions on farms could be even worse than is portrayed in this paper.

4. Demographic profile

Many respondents have been farm workers for their entire working lives. The majority of women interviewed are in their 30s (40%) or 40s (28%), a smaller number are under 30 (23%) and a minority are in their 50s (9%). Permanent workers interviewed are older on average (43% are over 40) than seasonal workers (69% are under 40), reflecting a rising casualisation of the agricultural labour force. Those who have worked on farms for less than 5 years are twice as likely to be seasonal workers (40%) than permanent workers (21%) – another indicator that new entrants to the sector have a greater chance of being employed as seasonal or casual workers and a much smaller chance than in the past of securing permanent contracts. It also illustrates the new ‘normal’ in the sector, where employment is increasingly precarious. Slightly more than half the survey respondents (56%) live on a farm, while just under half live off the farm (46%), with no significant difference between provinces. Not surprisingly, permanent employees are more likely to live on the farm where they work (64%) than are seasonal farm workers (41%).

Although two-thirds of women interviewed are either married or co-habiting (67%), one in three is single (33%) – never married, divorced or widowed. This implies that a significant proportion of farm women depend entirely on their own resources and have no other earned income. This is especially significant for women seasonal workers, who are only employed for part of the year.

5. Contracts, wages and deductions

The Sectoral Determination for Farm Workers states that all farm workers must have written contracts and must be paid at least the minimum wage, which is set at hourly, daily, weekly and monthly rates, and is updated every year. It further states that: ‘An employer may not make any deduction from a farm worker’s wage’ except for clearly prescribed items and within limits, usually ‘not exceeding 10 percent of the farm worker’s wage’ (Republic of South Africa Citation2006, para. 8). More than half of 343 farm women interviewed for this study (55%) are not familiar with the Sectoral Determination.

5.1. Contracts

An employer must supply a farm worker, when the farm worker starts work with the following particulars in writing … a brief description of the work for which the farm worker is employed … the farm worker’s ordinary hours of work … the farm worker’s wage … any deductions to be made from the farm worker’s wages (Republic of South Africa Citation2006, para. 9(1)).

Table 1. Contracts.

Most farm workers who did sign an employment contract understood the content of their contract (87%), and stated they had enough time to go through the contract (80%). However, some claim they were forced to sign a contract despite disagreeing with the contents. On one farm, seasonal workers who refused to sign a contract that exempted the farmer from liability if the truck transporting them had an accident were threatened with not being hired.

Among those farm workers who did sign contracts, more than 80% of seasonal workers, export market workers and workers in Western Cape did not receive a copy (). Typically, the supervisor or farmer simply read the contract to the workers and ordered them to sign it immediately. (‘You don’t get the contract to take home’.)

5.2. Wages

A minimum wage for farm workers in South Africa was introduced in 2003 under the first Sectoral Determination of 2002 and is increased annually, usually at about the Consumer Price Index plus 1%. Following the farm worker strike of 2012, the minimum wage was raised once-off by 52%. ‘[A]n employer must pay a farm worker at least the minimum wage prescribed’ (Republic of South Africa Citation2006, para. 2(1)).

Almost one in three farm workers surveyed (31%) did not know the current legal minimum wage rate (). Knowledge of the minimum wage is highest among permanent workers (75%) and lowest among seasonal workers (34%). Three in five workers believe they get paid the legal minimum wage (61%), while one in five believe they receive less than the minimum wage (21%). The highest proportion who reported that they do not get paid the minimum wage are workers in the domestic market (35%), followed by seasonal workers (30%) and workers in the Northern Cape (26%). (‘We are not paid the minimum wage, but what can we do?’)

Table 2. Wages.

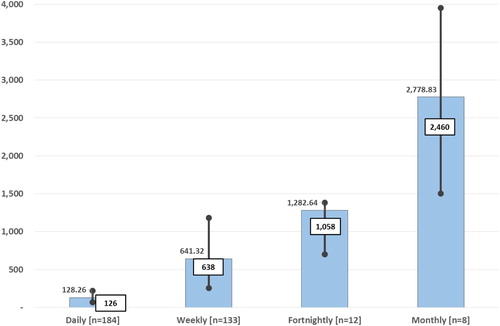

Most farm workers are paid weekly or fortnightly, and most know their wage as either a daily rate (55%) or a weekly rate (39%). The Sectoral Determination for Farm Workers set minimum wage rates for the period 1 March 2016 to 28 February 2017 at R128.26 a day, R641.32 a week, and R2,778.83 a month (Republic of South Africa Citation2016). Average self-reported wages in this survey were close to the legislated daily and weekly Sectoral Determination rates, but significantly lower than the monthly rate and the imputed fortnightly rate.

The daily wage rate reported in the survey ranged from a low of R70 to a high of R220, with a mean of R126 or 1.7% below the Sectoral Determination minimum wage rate. The weekly rate ranged from R255 to R1,181 with a mean of R638, very close to the Sectoral Determination rate. There is no legislated fortnightly minimum wage, but imputing this as twice the weekly minimum wage reveals that workers who are paid fortnightly receive 17.5% less than R1,283. The mean monthly wage rate in the survey was R2,460, which is 11.5% less than the Sectoral Determination rate of R2,779. The lowest monthly wage reported was R1,500 and the highest was R4,000 ().

Figure 1. Average self-reported wage rates relative to the Sectoral Determination, 2016/17. Source: Farm workers labour rights survey data.

Two in five farm workers surveyed (41%) are paid below the Sectoral Determination minimum wage rate (). Those who are paid fortnightly or monthly are worst off: not only are their average wages further below the minimum wage than those who are paid a daily or weekly rate, but 75% of fortnightly or monthly wages are less than the legal minimum. On the other hand, 20% of daily wage rates and 29% of weekly wage rates are above the legal minimum ().

Table 3. Wage rates relative to the Sectoral Determination.

5.3. Deductions

Almost 80% of farm women interviewed have deductions made from their wages, meaning they do not receive their payment in full. Some deductions are legitimate. In terms of the Unemployment Insurance Act, all employers should register their workers with the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) and should deduct UIF contributions from workers’ wages. Seasonal workers – defined as ‘any person who is employed by an employer for an aggregate period of at least three months over a 12 month period with the same employer and whose work is interrupted by reason of a seasonal variation in the availability of work’ (Republic of South Africa Citation2001, para. 1) – were initially excluded from the UIF, but are now included.

UIF deductions are close to universal (>90%) in Western Cape, for permanent workers and for export market workers. On the other hand, more than half of domestic market workers (58%) and two in five seasonal workers (40%) and workers in Northern Cape (43%) do not have UIF contributions deducted from their wages (). This is problematic as workers who do not make UIF payments cannot claim unemployment insurance when they need it. Women are especially adversely affected as most are seasonal workers, and very few get paid maternity leave.

Table 4. Deductions from wages.

Apart from this social security contribution, farmers make deductions from workers’ pay-packets for housing expenses such as rent (12% of respondents) and electricity (17%), or for employment-related expenses such as work clothes (8%) and transport to and from work (5%) (). Farmers also deduct money for funeral policies for farm workers (15%), although some workers are suspicious about whether these premiums are actually paid. In one case, a farmer who made deductions every month, supposedly for a funeral policy, told a worker when she needed a pay-out that the policy had lapsed.

Some farmers give loans or advances to workers, repayments for which are also deducted from wage packets. Other deductions mentioned are for health costs, medical aid, union fees, TV rental, savings, rent for children, and to pay off accounts at the farm shop. Farm workers buy food and groceries from farm shops for convenience and because the farmer allows them to buy on credit. However, commodities sold in farm shops are often unreasonably expensive. Some women also reported that farmers charge them extra rent for children over 18 who do not work on the farm, in contravention of the Extension of Security of Tenure Act. These are all strategies that farmers use to recoup some labour costs directly from their workers.

6. Occupational health and safety

The Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) affirms that: ‘Every employer shall provide and maintain, as far as is reasonably practicable, a working environment that is safe and without risk to the health of his [sic] employees’ (Republic of South Africa Citation1993a, para. 8(1)). Occupational health and safety issues explored in this research include access to water and sanitation facilities at worksites, compensation for injuries at work, exposure to pesticides and use of protective clothing.

6.1. Hygiene and sanitation

Almost two-thirds of farm women surveyed (63%) do not have a toilet in vineyards where they work. This situation is worse for workers in the Northern Cape (71%) and for seasonal workers (72%), but is worst of all for workers employed on farms producing for the domestic market (84%). Half the women interviewed (50%) have no access to washing facilities in their vineyards. Again, this situation is worse for workers in the Northern Cape than the Western Cape, for seasonal rather than permanent workers, and for export rather than domestic market workers (). Farm women’s labour rights are violated by the lack of toilets in the vineyards, their dignity is compromised as they are forced to seek alternatives, and negative health implications follow from their lack of access to water for drinking and washing their hands after relieving themselves and before eating.

Table 5. Lack of access to toilets and wash facilities at the workplace.

Women who have no toilets at their workplace must use the bush (47%) or a secluded part of the vineyard or orchard (40%). Asked how they feel about this situation, most replied that it makes them feel ‘uncomfortable’ and ‘unsafe’, while some expressed anger and unhappiness and stated that it is ‘dangerous and humiliating’. Women who use the bush are at risk of sexual harassment or worse, and for this reason they try to walk in groups when they need to use the bush.

Even if toilets are provided, they are not necessarily hygienic. (‘They are never cleaned’.) Women face additional difficulties when they are menstruating, when they are forced to use the bush to change their sanitary towels. (‘You fear being raped. You don’t have any dignity doing that’.) Women’s lack of access to toilets and sanitation facilities is a form of gender discrimination, as their gender-specific needs are neither acknowledged nor accommodated.

6.2. Work injuries and compensation

More than one in three farm women interviewed are not familiar with the Occupational Health and Safety Act, and do not know the correct procedure to follow if they get injured at work (). The Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (COIDA) affirms that employees who suffer an occupational injury or disability at work are entitled to compensation from the Compensation Fund. All employers in South Africa are required to register with the Compensation Commissioner and to report any accident reported by employees to the Commissioner, who considers the claim and determines whether compensation should be paid. Seasonal workers are less likely than permanent workers to be familiar with the Act or the procedure to follow in case of injury while working. Many farmers take advantage of this lack of familiarity and do not report work-related injuries to the Department of Labour, nor do they register with the Compensation Fund.

Table 6. Health and safety at the workplace.

Many farm women know somebody who was injured while at work. Only half of these incidents were reported to the Department of Labour (51%). The chances of injuries being reported are much lower in the Northern Cape (37%), for seasonal workers (37%) and for domestic market workers (38%). Less than two-thirds of these injured farm workers were compensated for their injury (62%) (). Often workers have to pay for medical attention when they are injured on duty, either directly or by deductions from their wages. (‘The farmer pays but then he takes it off your wages’.) Other workers do not report injuries and continue working, for fear of losing income or even their jobs.

6.3. Exposure to pesticides

The Occupational Health and Safety Act instructs employers to take steps ‘to eliminate or mitigate any hazard or potential hazard to the safety or health of employees’ (Republic of South Africa Citation1993a, para. 8(2b)). Employers should not permit any employee to work with or handle any hazardous substance, unless appropriate precautionary measures have been taken. Employers must ‘ensure that information is available with regard to the use of the substance at work, the risks to health and safety associated with such substance … and the procedures to be followed in the case of an accident involving such substance’ (Republic of South Africa Citation1993a, para. 10(3)). The Hazardous Chemical Substances Regulations (Republic of South Africa Citation1995b) requires employers to provide any employee who is exposed to hazardous chemicals, including pesticides, with appropriate protective clothing.

Two-thirds of farm workers surveyed are exposed to pesticides at work (67%), but only one in four (27%) have been told which pesticides are used and their possible side-effects (). Four in five farm women from Northern Cape (79%) and seasonal farm workers (82%), and almost all domestic market workers (93%) have not been given any information about the pesticides that are used on the farms where they work and the associated risks to their health.

Table 7. Exposure to pesticides.

Almost one-third of workers who work with pesticides have no separate washing facility (70%), meaning they have to clean themselves and their clothes at home, thereby exposing their families to a potential health hazard. On one farm it was reported that washing facilities are only provided during farm audit visits by Labour Inspectors. (‘When they leave, the facilities are removed’.)

Surveys in the Western Cape have found elevated levels of harmful chemicals in blood samples taken from farm workers after pesticides were sprayed (London Citation2003; Dalvie et al. Citation2009). A significant proportion of farm women interviewed for this research (39%) come into contact with pesticides less than one hour after they have been applied – or even during spraying – and this risk of exposure seems to be gendered. (‘Women don’t work with pesticides, but they spray in the vineyard while we are busy working’.) In a reverse of most other findings, farm women in Western Cape, permanent and export market workers are at higher risk of immediate post-application contact with pesticides than Northern Cape, seasonal and domestic market farm women, respectively ().

Those who work with or are exposed to pesticides reported a range of negative health side-effects. Most common are skin problems (e.g. rash), which has affected one in four farm workers in Western Cape and permanent workers, followed by nasal problems, eye problems, breathing difficulties, headache and nausea, each affecting at least one in 10 farm workers. Family members of workers who live on farms can also be adversely affected. (‘Children also get sick from the pesticides’.)

Two-thirds of farm workers surveyed who are exposed to pesticides are not provided with protective clothes by the farmer (66%). This figure rises to almost three-quarters of seasonal workers (73%) and workers in Northern Cape (74%), and nine in ten workers on domestic market farms (89%), but it exceeds 50% even among Western Cape and permanent farm workers (). Some men appear to be better protected than women, both in the fields and in the packing rooms. (‘Only the man who drives the tractor and sprays has protective clothes’. ‘Working in the cold store, we don’t receive any protective clothes or waterproof boots for the cold and wet’.)

According to OHSA: ‘No employer shall in respect of anything which he is in terms of this Act required to provide or to do in the interest of the health or safety of an employee, make any deduction from any employee’s remuneration’ (Republic of South Africa Citation1993a, para. 23). However, many farmers violate this requirement, either by forcing workers to buy their own protective clothing or by deducting the cost from their wages. (‘If you want clothes, you have to pay for it yourself’. ‘The farmer buys the workers overalls and safety shoes but the workers have to pay for them’.)

7. Upholding labour rights on farms

Three sets of actors have a role in ensuring that workers’ rights on farms are upheld: employers (farmers and farm managers), government (specifically the Department of Labour) and workers’ organisations (trade unions). This section presents evidence that all three are failing in this responsibility.

7.1. Trade unions

Section 23 of the Constitution upholds the right of workers to join and participate in a trade union and the right to strike. Trade union membership is low among farm workers in South Africa, and stands at only 12% in our survey. (‘On the farm where I work there is nobody who is a member of a union’.) Union membership is marginally higher in the Western Cape and among permanent or export market workers. Almost one-third of these farm women was either a union member in the past or has been approached about joining a union (30%). Northern Cape, seasonal and domestic market workers are less likely to be union members, or to have been approached (). (‘Nobody ever talked to me about a union’.)

Table 8. Trade unions.

One reason for this is the geographical isolation and inaccessibility of commercial farms, which makes awareness raising and recruitment challenging. (‘I don’t know where or who I should go to, to become a member’.) Many respondents believe (incorrectly) that no unions exist specifically for farm workers, or that seasonal workers are not allowed to join. (‘I am only a seasonal worker and unions are for permanent workers’.)

A few women replied that they have no interest in trade unions. (‘I have not seen the need to join one’.) One reason for this lack of interest is financial – the costs of joining and paying membership fees. (‘We already have a lot of money deducted from our salary’.) A second factor is distrust – some respondents believe that unions do little to assist farm workers and are only interested in collecting fees. (‘Unions just take our money while they don’t do anything for us’.) Some farm women who had previously been trade union members became disillusioned and left.

However, the main reasons given for low union membership relate to the hostile attitude of employers. Almost three-quarters of farm workers surveyed stated that farmers do not allow union representatives access to their farm (73%). Several women claimed that farmers prohibit them (illegally) from joining unions. (‘The farmer said no’.) More than half of women interviewed stated that their employer does not allow farm workers to attend union meetings (54%), and this figure is higher in Northern Cape (67%), for domestic market workers (65%) and for seasonal workers (60%) ().

Farmers are widely perceived by farm workers as being hostile to trade unions, because they fear that workers could use the union to campaign for higher wages and better working conditions. (‘The farmer doesn’t want us to know our rights’.) Many workers admitted that they have not joined a union because they fear reprisals from their employer. (‘We are afraid of the farmer and he does not let us join the union’.)

7.2. Labour inspections

Inspectors from the Department of Labour are expected to make regular visits to workplaces, including commercial farms, to monitor working conditions and employers’ compliance with labour laws and regulations. But the Department’s capacity is severely constrained. In 2011 there were only 107 labour inspectors monitoring all workplaces in the Western Cape, including over 6,000 farms. Moreover, under an agreement between the Department of Labour and the farmers’ association Agri South Africa, labour inspectors have to give farmers advance warning of inspections (Human Rights Watch Citation2011).

A significant proportion of workers surveyed (41%) do not know whether their farm has ever been inspected by the Department of Labour. (‘I have never seen them’.) Many others (28%) claimed that labour inspectors have never visited their farms. One respondent asserted that farmers actively prevent inspectors from conducting inspections. (‘The inspectors are not allowed on the farm’.)

Less than one in three respondents (31%) reported that their farm has been visited by labour inspectors (). Half of these reported that visits were made every 6–12 months (16%), while a smaller number said these visits occur every 3–6 months (10%) or every 1–3 months (5%). Many women stated that when labour inspectors visit their farm they only interview the farmer. (‘The Department of Labour comes to our farm, but they never speak to the workers’.) Some workers insist that they should be invited to meet the labour inspectors. (‘It is my right to know if there are inspectors coming to the farm’.)

Table 9. Farm visits by Department of Labour inspectors.

8. Conclusion

Five prerequisites for effective protection of workers’ rights emerge from this research: progressive labour legislation, compliance by employers, monitoring by labour inspectors, activism by NGOs and trade unions, and punitive penalties for violations. In South Africa’s commercial agriculture sector, all five requirements were absent until the late 1990s, when pro-worker labour laws were introduced. However, this research has shown that, 20 years later, non-compliance by employers remains the rule rather than the exception.

Many farm workers interviewed have never signed an employment contract and are paid less than the statutory minimum wage. Employers make deductions from pay-packets to avoid paying full wages and many do not pay unemployment insurance contributions for their workers. The majority of women surveyed do not have access to toilets while working in vineyards and orchards. Injuries at work often go unreported so workers do not get the compensation they are entitled to under COIDA, and many injured workers have to pay their own medical bills. A high proportion of workers are exposed to pesticides that causes health problems such as skin rashes and breathing difficulties, but farmers rarely provide protective clothing.

A fundamental reason for these ongoing violations of the full spectrum of farm workers’ rights is that farmers have little incentive to comply with the laws. Firstly, the risk of being caught is extremely low – in 2007, for instance, only 11% of farms in the Western Cape were visited by a Labour Inspector (Stanwix Citation2013), who gives notice in advance and typically speaks only to the farmer, or to workers with the farmer present. Most farm workers surveyed for this study have never seen a Labour Inspector visit the farms where they work. Secondly, even if the employer is caught underpaying workers, the punishment is trivial: for a first offence, just 25% of the underpaid amount, according to the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (Republic of South Africa Citation1997a).

A more general conclusion is that the replacement of ‘racialised paternalism’ on farms with legislated labour rights has had the unintended consequence of removing non-wage benefits that farmers used to provide informally which have not been replaced, as farmers engage strategies to evade legislation and deliver as little as possible to their workers. What used to be accepted as the responsibility of farmers is now seen as the responsibility of the ANC government. As one farm worker in another study pithily explained: ‘In the past the farmer used to drive my kids to the hospital, now he says: let Mandela take your children to hospital’ (Lemke & Jansen van Rensburg Citation2014:854).

Finally, unionisation of farm workers is extremely low, with most interviewees reporting that farmers actively discourage or prohibit them from joining a union, in direct violation of section 23 of the Constitution. Union officials admit that they find recruitment of farm workers ‘strenuous and costly’, due to the remoteness and dispersion of farms and the difficulty of gaining access (Pahle Citation2015:132). During the farm worker strike of 2012/13 union leaders featured prominently in the media, often claiming credit for mobilising farm workers. Before and after the strike, however, trade unions featured relatively little in the lives of most farm workers (Eriksson Citation2017). Wilderman (Citation2015:13) showed that the strike was instigated by community-based activists and local ‘coordinating units’, not by unions.

It follows that the interests of farm workers might not be best advanced through mainstream labour organisations. In this context, grassroots NGOs such as Women on Farms Project, Surplus People Project and the Trust for Community Outreach and Education (TCOE) play invaluable roles in supporting farm workers, through sensitising them about their rights, mobilising them to claim these rights, and campaigning for their improved lives and livelihoods.

Within the commercial agriculture sector, some workers are treated better (or less badly) than others. Survey findings indicate that farm workers are generally worse off in the geographically remote Northern Cape province than the Western Cape, with its lucrative and tourist-friendly Wine Route. Farm workers in the export sector, especially wine, are relatively better off than those who produce table grapes and citrus fruit for local supermarkets, possibly because export farmers need to comply with international trade regulations and ethical audits. Permanent workers are better protected by labour legislation than seasonal workers, especially those who have been evicted and are re-employed on short-term contracts. Summing up these findings, an archetypal marginalised worker in South Africa in 2019 is a seasonal farm woman working on a raisin farm in the Northern Cape.

Despite all the progressive legislation introduced after 1994, farm workers are even more vulnerable than before. This is not to blame the pro-worker legislation, which was necessary and long overdue. Rather, farmers are to blame for refusing to comply, government is implicated for not enforcing compliance, and trade unions must do more to hold both farmers and government accountable.

Acknowledgements

This research was commissioned by Women on Farms Project and funded by Oxfam Germany and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). This research would not have been possible without the participation of staff from Women on Farms Project and hundreds of women farm workers in the Western Cape and Northern Cape who contributed at all stages of the study, from design to data collection to data validation. Glenise Levendal and Enya Yde contributed substantially to the research design and data analysis respectively. Thanks to Colette Solomon and two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Opinions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of Women on Farms Project, Oxfam Germany, BMZ, the National Research Foundation or the Newton Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Stephen Devereux http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4885-0085

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The dop system refers to partial payment of farm workers with wine, which was used as a mechanism of social control (London Citation1999; Williams Citation2016) and contributed to the Western Cape having one of the world’s highest rates of foetal alcohol syndrome (London Citation2003).

2 Following Adhikari’s analysis of Coloured identity, in this paper ‘the term black is used in its inclusive sense to refer to Coloured, Indian, and African people collectively, and African is used to refer to the indigenous Bantu-speaking peoples of South Africa’ (Adhikari Citation2005: xv). The term ‘Coloured’ is an apartheid racial classification but also a culturally constructed identity, sometimes chosen and sometimes rejected, that describes both ‘mixed race’ descendants of African or Asian slaves and European settlers, as well as the indigenous Khoisan people. It also includes subgroups such as the Cape Malay and Griqua peoples.

3 A similar anxiety about engaging with researchers was expressed by farm workers in a recent study of labour relations on commercial farms in Eastern Cape, ‘due to the constant threat of losing jobs' (Brandt & Ncapayi Citation2016: 217).

4 All direct quotations in italics are statements made in focus group discussions by women farm workers. No additional identifying information is provided, to protect their anonymity. Discussions were conducted in Afrikaans and audio-recorded, and these recordings were deleted after transcription.

References

- Addison, L, 2014. Delegated despotism: Frontiers of agrarian labour on a South African border farm. Journal of Agrarian Change 14(2), 286–304. doi: 10.1111/joac.12062

- Adhikari, M, 2005. Not white enough, not black enough: Racial identity in the South African coloured community. Double Storey Books, Cape Town.

- Atkinson, D, 2007. Going for broke: The fate of farm workers in arid South Africa. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Bernstein, H, 1996. South Africa’s agrarian question: Extreme and exceptional? Journal of Peasant Studies 23(2-3), 1–52. doi: 10.1080/03066159608438607

- Bernstein, H, 2013. Commercial agriculture in South Africa since 1994: ‘Natural, simply capitalism’. Journal of Agrarian Change 13(1), 23–46. doi: 10.1111/joac.12011

- BFAP (Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy), 2012. Farm Sectoral Determination: An analysis of agricultural wages in South Africa. Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy, Pretoria.

- Bhorat, H, Kanbur, R & Stanwix, B, 2012. Estimating the impact of minimum wages on employment, wages and non-wage benefits: The case of agriculture in South Africa. DPRU working paper, 12/149. Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Bolt, M, 2017. Becoming and unbecoming farm workers in Southern Africa. Anthropology Southern Africa 40(4), 241–7. doi: 10.1080/23323256.2017.1406313

- Brandt, F & Ncapayi, F, 2016. The meaning of compliance with land and labour legislation: Understanding justice through farm workers’ experiences in the Eastern Cape. Anthropology Southern Africa 39(3), 215–31. doi: 10.1080/23323256.2016.1211020

- Dalvie, M, Africa, A, Solomons, A, London, L, Brouwer, D & Kromhout, H, 2009. Pesticide exposure and blood endosulfan levels after first season spray amongst farm workers in the Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B 44, 271–7. doi: 10.1080/03601230902728351

- Devereux, S, Levendal, G & Yde, E, 2017. ‘The farmer doesn’t recognise who makes him rich’: Understanding the labour conditions of women farm workers in the Western Cape and the Northern Cape, South Africa. Women on Farms Project, Stellenbosch.

- du Toit, A, 1992. The farm as family: Paternalism, management and modernisation on Western Cape wine and fruit farms. Centre for Rural Legal Studies, Stellenbosch.

- Eriksson, A, 2017. Farm worker identities contested and reimagined: Gender, race/ethnicity and nationality in the post-strike moment. Anthropology Southern Africa 40(4), 248–60. doi: 10.1080/23323256.2017.1401484

- Greyling, J, Vink, N & Mabaya, E, 2015. South Africa’s agricultural sector twenty years after democracy (1994 to 2013). Professional Agricultural Workers Journal 3(1), 1–14.

- Hall, R, 2009. Dynamics in the commercial farming sector. Chapter 5. In R Hall (Ed.), Another countryside? Policy options for land and agrarian reform in South Africa. Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, 121–31.

- Hall, R & Cousins, B, 2018. Exporting contradictions: The expansion of South African agrarian capital within Africa. Globalizations 15(1), 12–31. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2017.1408335

- Hall, R, Wisborg, P, Shirinda, S & Zamchiya, P, 2013. Farm workers and farm dwellers in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Journal of Agrarian Change 13(1), 47–70. doi: 10.1111/joac.12002

- Human Rights Watch, 2011. Ripe with abuse: Human rights conditions in South Africa’s fruit and wine industries. Human Rights Watch, New York.

- Lemke, S & Jansen van Rensburg, F, 2014. Remaining at the margins: Case study of farmworkers in the North West Province, South Africa. Development Southern Africa 31(6), 843–58. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2014.951990

- Liebenberg, F & Pardey, P, 2010. South African agricultural production and productivity patterns. Chapter 13. In J Alston, B Babcock & P Pardey (Eds.), The shifting patterns of agricultural production and productivity worldwide. Center for Agricultural and Rural Development, Iowa State University, Ames, 383–408.

- Lipton, M, 1986. Capitalism and apartheid: South Africa, 1910–1986. David Philip, Cape Town.

- London, L, 1999. The ‘dop’ system, alcohol abuse and social control amongst farm workers in South Africa: A public health challenge. Social Science and Medicine 48, 1407–14. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00445-6

- London, L, 2003. Human rights, environmental justice, and the health of farm workers in South Africa. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 9(1), 59–68. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2003.9.1.59

- Naidoo, L, Klerck, G & Manganeng, L, 2007. The ‘bite’ of a minimum wage: Enforcement of and compliance with the Sectoral Determination for farm workers. South African Journal of Labour Relations 31(1), 25–46.

- Pahle, S, 2015. Stepchildren of liberation: South African farm workers’ elusive rights to organise and bargain collectively. Journal of Southern African Studies 41(1), 121–40. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2015.992718

- Phuhlisani, 2017. Tenure security of farm workers and dwellers, 1994–2016. Commissioned report for high level panel on the assessment of key legislation and the acceleration of fundamental change, an initiative of the Parliament of South Africa. Phuhlisani, Cape Town.

- Ranchhod, V & Bassier, I, 2017. Estimating the wage and employment effects of a large increase in South Africa’s agricultural minimum wage. REDI3x3 working paper, 38. SALDRU, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Republic of South Africa, 1993a. Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) (Act No. 85 of 1993). Department of Labour, Pretoria.

- Republic of South Africa, 1993b. Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (COIDA) (Act No. 130 of 1993). Department of Labour, Pretoria.

- Republic of South Africa, 1995a. Labour Relations Act (LRA) (Act No. 66 of 1995). Department of Labour, Pretoria.

- Republic of South Africa, 1995b. Hazardous Chemical Substances Regulations (Regulation No. 1179, 27 August 1995). Department of Labour, Pretoria.

- Republic of South Africa, 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act No. 108 of 1996). Constitutional Assembly, Cape Town.

- Republic of South Africa, 1997a. Basic Conditions of Employment Act (BCEA) (Act No. 75 of 1997). Department of Labour, Pretoria.

- Republic of South Africa, 1997b. Extension of Tenure of Security Act (ESTA) (Act No. 62 of 1997), Vol. 389, No. 18467. Government Gazette, Cape Town.

- Republic of South Africa, 2001. Unemployment Insurance Act (UI) (Act No. 63 of 2001). Department of Labour, Pretoria.

- Republic of South Africa, 2006. Sectoral Determination 13: Farm Worker Sector, South Africa. Department of Labour, Pretoria.

- Republic of South Africa, 2016, Sectoral Determination 13, farm worker sector, South Africa. Government Gazette, Vol. 608, No. 39648. Government Printing Works, Pretoria.

- Roberts, T & Antrobus, G, 2013. Farmers’ perceptions of the impact of legislation on farm workers’ wages and working conditions: an Eastern Cape case study. Agrekon 52(1), 40–67. doi: 10.1080/03031853.2013.778464

- SAWIS (South African Wine Industry Information and Systems), 2014. South African wine exports analysis, 2008–2013. www.wosa.co.za/knowledge/pkdownloaddocument.aspx?docid=3239. Accessed 6 August 2018.

- Sparrow, G, Ortmann, G, Lyne, M & Darroch, M, 2008. Determinants of the demand for regular farm labour in South Africa, 1960–2002. Agrekon 47(1), 52–75. doi: 10.1080/03031853.2008.9523790

- Stanwix, B, 2013. Minimum wages and compliance in South African agriculture. Econ 3x3. Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Terreblanche, S, 2002. A history of inequality in South Africa. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Scottsville.

- Van Onselen, C, 1991. The social and economic underpinnings of paternalism and violence on the maize farms of the south-western Transvaal, 1900-1950. African studies seminar paper. African Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Van Zyl, J & Vink, N, 1988. Employment and growth in South Africa: An agricultural perspective. Development Southern Africa 5(2), 196–207. doi: 10.1080/03768358808439394

- Visser, M & Ferrer, S, 2015. Farm workers’ living and working conditions in South Africa: Key trends, emergent issues, and underlying and structural problems. International Labour Organisation, Pretoria.

- Waldman, L, 1996, Monkey in a spiderweb: The dynamics of farmer control and paternalism. African Studies 55(1), 62–86. doi: 10.1080/00020189608707840

- Wegerif, M, Russell, B & Grundling, I, 2005. Still searching for security: The reality of farm dweller evictions in South Africa. Nkuzi Development Association and Social Surveys, Polokwane.

- Wilderman, J, 2015. From flexible work to mass uprising: The Western Cape farm workers’ struggle. SWOP working paper, 4. Society, Work and Development Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Williams, G, 2016. Slaves, workers, and wine: The ‘dop system’ in the history of the Cape wine industry, 1658–1894. Journal of Southern African Studies 42(5), 893–909. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1234120

- Women on Farms Project, 2011. Towards an understanding of farm worker evictions: The case study of Rawsonville. Mimeo. Women on Farms Project, Stellenbosch.