ABSTRACT

South Africa is a paradox; on the one hand, it is one of the most unequal countries in the world. Half of all South Africans continue to live in poverty, economic growth has stagnated and inflation remains high, while the unemployment rate continues to climb towards 30%. On the other hand, it has one of the most progressive constitutions in the world, with a bill of rights that foregrounds expanded socioeconomic rights. We provide an overview of the latest statistics on poverty and inequality in light of overarching economic policies, and the socioeconomic guarantees of the Constitution. We argue that South Africa’s inability to meaningfully address the high levels of inequality is due to insufficient attention to the way power reproduces inequality. We present a definition of power that includes social and market power, and emphasise the importance of a theory of power in understanding the reproduction of inequality.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

South Africa is something of a paradox; on the one hand, it is one of the most unequal countries in the world, if not the most unequal. Half of all South Africans continue to live in poverty, and there is little to indicate that the poorest will see a reversal in their misfortunes in the coming years – indeed, the most recent data indicates that poverty is rising from 2011, after almost two decades of steady declines (Statistics South Africa, Citation2017). Economic growth has stagnated, and inflation remains high relative to the developed world, while the unemployment rate continues to climb towards 30%. On the other hand, it has one of the most progressive constitutions in the world with a bill of rights that foregrounds expanded social and economic rights. It retains a robust and critical media, a vibrant civil society and an active and independent judiciary. It is a country that sits at the nexus of several competing, and possibly incompatible, forces: it is a small, open economy participating fully in international trade and finance; and its socio-economic situation requires radical policy action.

This article provides an overview of the latest statistics on poverty and inequality in light of the overarching economic policy of the National Development Plan, and the socioeconomic guarantees of the Constitution. The primacy of the Constitution as the normative framework in South Africa means that any discussion of socioeconomic rights and economic policy must take place with regard to the Constitution. We use the framework of the South African Constitution to evaluate progress in ending poverty and reducing inequality. We argue that South Africa’s historical inability to meaningfully address the high levels of inequality is due, in part, to insufficient attention to the way power produces and reproduces the conditions that facilitate growing inequality. The progress which South Africa has made in gradually reducing poverty, compared to the intransigence of inequality points to the fundamental difference between the two: while poverty is characterised by an absence which can be addressed by policies of provision, inequality is a relational phenomenon which is mediated by power (Soudien et al., Citation2019). In a country such as South Africa, poverty and inequality are closely interlinked, and despite their differences, it is impossible to consider one in the absence of the other.

We proceed as follows. Firstly, we discuss the history of poverty and inequality in South Africa, with a focus both on trends, and the nature and extent of research into these areas. We then identify key drivers of inequality, using the lens of a macroeconomic and labour market analysis, and we examine the role of power in the reproduction of inequality. We survey the key policy measures that have been adopted to combat poverty and inequality, paying particular attention to the role of the South African Constitution in delivering both formal and substantive socio-economic rights. Finally, we examine policies to address these issues in South Africa.

2. From the study of poverty to the study of inequality

South Africa has a long history of studying poverty, while a focus on inequality has only more recently entered into academic and policy discourse. The first comprehensive study of poverty dates back to 1932, when the first Carnegie Inquiry was held into the nature and causes of poverty amongst the European settler community. In the 1970s, the Theron commission investigate the socio-economic position of Coloured South Africans (Van der Horst, Citation1976). In the nineteen eighties, a second commission into poverty was undertaken, Carnegie Two, where the focus was largely on poverty in the majority black community (Wilson & Ramphele, Citation1994). The approach of Carnegie Two was captured in these words;

Poverty is a profoundly political issue … there are four reasons why poverty is significant. The first is because of the damage it inflicts upon individuals who must endure it; the second is its sheer inefficiency in economic terms. Hungry children cannot study properly; malnourished adults cannot be fully productive as workers; and an economy where a large proportion of the population is very poor has a structure of demand that does not encourage the production and marketing of those goods that are most needed. The third reason relates to the consequences for any society where poverty is also the manifestation of great inequality. As Raymond Aron has reminded us, the existence of too great a degree of inequality makes human community impossible. Finally, there is the fact that poverty in many societies is itself symptomatic of a deeper malaise. For it is often the consequence of a process which simultaneously produces wealth for some whilst impoverishing others. (Wilson & Ramphele, Citation1994:4)

The alternative narrative of South Africa’s inequality argues that the distribution of income and market power in South Africa (rather than the unequal distribution of capabilities) is a potential leading causal factor driving inequality. Indeed, market power is the defining characteristic of the global rules governing investment and trade. As Therborn argues, inequality of power has so far only rarely been included in studies and analyses of social inequalities, and when ‘political inequality’ is addressed, it usually refers to inequalities of voting and of other forms of political participation. It should be taken more seriously, and related to different kinds of regimes: the constellations of power (Therborn, Citation2013:51).

This perspective requires that the distribution of economic power be addressed and takes account of the very divergent conditions of low-and-high income households or of townships and suburbs. It requires a bolder and more integrated approach combining inclusive growth strategies, substantial social protection, capability development and labour activation at a scale sufficient to reconfigure structural deficiencies in the distribution of power. Addressing this inequality requires an understanding of power that goes beyond market power, and seeks to understand how power manifests in structural and institutional exclusion and discrimination, and how it operates at the intersection of identities within society. Indeed, power is produced and reproduced at the intersection of race, class, gender and sexuality and other aspects of identity,Footnote1 in addition to its economic and spatial dimensions. An intersectional approach is necessary in order to understand the way in which these different dimensions of power interact to reproduce inequality. While power underpins all social relations, it is often taken for granted or completely overlooked as it is often hidden behind other social relations.

2.1. Measuring poverty and inequality: a disclaimer

In a comparative paper, there is a temptation to reduce the quantification of poverty to a set of easily comparable indicators. However, given South Africa’s history, some care is required in understanding the different forms of poverty faced by South Africans, and the ways in which poverty is manifested. As argued in the second Carnegie Inquiry:

In seeking to define the phenomenon [of poverty] we must be careful not to confine our thinking to those characteristics that appear important to people living within the sheltered walls of an urban university … We do not wish to be misunderstood: statistical analysis is essential, and the effort to toughen up the soft social sciences by improving the quality of statistics is one of the most significant intellectual advances of our time. But precisely because the numbers are so important it is vital to pause at the beginning to consider what we are measuring and, perhaps even more significant, what we are not measuring. (Wilson & Ramphele, Citation1994:14–5)

3. Poverty in post-apartheid South Africa

The end of Apartheid in the early 1990s, and the first democratic elections in 1994, thrust South Africa into an exciting new political era, but left it encumbered with vast inequalities across the race groups, and extensive and deep poverty. In some respects, South Africa has made significant progress in reducing poverty. One of the key policy interventions in this regard has been the wide-spread roll-out of a social assistance programme in the form of social grants, coupled with a highly redistributive fiscal policy. While there is not provision for the working age population, grants are provided to carers of children under the age of 18, the disabled, and pensioners. A World Bank report in 2014 found that 70% of social grant spending, and 54% of spending on education and health are directed to the poorest half of the population. According the findings, social grants and the provision of free basic services (such as water and electricity) lift the incomes of approximately 3.6 million South Africans above US$2.50 per day (purchasing power parity), which resulted in the rate of extreme poverty being cut by half, to 16.5% from 34.4% between the end of apartheid and 2011 (World Bank, Citation2014).

Comparing current poverty statistics to those at the turn of the twenty-first century, Finn & Leibbrandt (Citation2017) find that there is general consensus that money-metric poverty has declined in South Africa. They note that ‘various cross-sectional studies of poverty using household survey data have chronicled a decline in the poverty headcount that is largely attributable to the role of state support of household incomes’ (Finn & Leibbrandt, Citation2017:2). Indeed, they find that access to a state social grant was the main cause of individuals exiting poverty, accounting for 23% of those who moved out of poverty between waves of the National Income Dynamics Survey (NIDS).

More recently, however, the progress on addressing poverty appears to have stalled. In a 2017 report by Statistics South Africa, the most-recent poverty statistics showed that despite a decline in poverty between 2006 and 2011, poverty levels had once again risen by 2015. From a low of 53.2% in 2011, by 2015, over half of all South Africans (55.5%), 30.4 million people, were living in poverty. This is according to the upper-bound poverty line of R992 per person per month, in 2015 prices (Statistics South Africa, Citation2017). Worryingly, poverty is highest among young people, with 63.7% of children under 17 years and 58.6% of 18–24 year-olds living in poverty, compared to 40.4% of 45–54 year-olds. However, this is an improvement from 2006, when 66.5% of South Africans were living below the upper-bound poverty line (Statistics South Africa, Citation2017).

Poverty in South Africa continues to reflect the historical and contemporary racial divisions in the country. According to Finn (Citation2015), in 2015 only 4.1% of white South Africans were classed as poor, compared to 20.5% of Asian/Indians, 56.8% of coloureds (a South African term referring to those of mixed-race parentage) and 70.75% of black South Africans ().

Table 1. Race and poverty in South Africa, 2015.

4. Inequality in post-apartheid South Africa

The first and most important point to make about understanding inequality is that it is not only a contemporary phenomenon. The current distribution of wealth and income has historical routes that go back several centuries, as detailed in the seminal contribution on inequality in South Africa by Terreblanche (Citation2002). In their extensive review of inequality trends in South Africa, Hundenborn et al. (Citation2016) find that overall inequality in South Africa, according to the Gini coefficient of income, decreased slightly between 1993 and 2014, from 0.681 to 0.655, despite a temporary increase accompanying the global financial crisis, when inequality rose to 0.69 in 2008 (Hundenborn et al., Citation2016). Finn (Citation2015) calculates the Gini coefficient of income at 0.66 for 2015. This means that there has been no significant reduction in overall inequality in post-apartheid South Africa. Writing at the start of the 1990s, Wilson & Ramphele (Citation1994) found that South Africa had the highest Gini coefficient of income of all 57 countries for which there were data at that time, at 0.66.

Inequality in South Africa is maintained by several structural forces which cannot be understood in isolation from the structures of economic and social power that were entrenched under apartheid, many of which persist today. In his testimony before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1997, Sampie Terreblanche argued that apartheid and South Africa’s capitalist system were mutually reinforcing (Terreblanche, Citation1997).Footnote2 This is contrary to a popular view, argued by Lipton, among others, that capitalism and the apartheid regime were mutually self-defeating (Lipton, Citation1986). The capitalist system in contemporary South Africa continues to reproduce inequality across all areas of social and economic life, despite the demise of apartheid. Income inequality in South Africa remains high, and is driven predominantly by wage inequality. Indeed, as Finn (Citation2015) shows, wage inequality accounts for 91% of overall income inequality in South Africa, or 0.6 of the 0.66 Gini coefficient for income ().

Table 2. Components of income inequality in South Africa.

But inequality in South Africa is not only a phenomenon between race groups: evidence from the post-apartheid period shows that intra-race inequality has grown at a rapid rate, and by 2009, intra-race inequality exceeded inter-race inequality. In 1993, inequality within race groups accounted for 48% of overall inequality; by 2008 this had increased to 62% (Leibbrandt et al., Citation2012). The declined of inter-race inequality points to the need to introduce a class-based approach to understanding inequality, not as an alternative to race- based inequality, but in order to show how race and class intersect.Footnote3 This suggests, not a declining significance of race, but that power is produced and reproduced at the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality and other aspects of identity. One illustration of this can be seen in the ‘Fees Must Fall’ student protests of 2016 and 2017. The demonstrations drew attention inequality in access to university education, and highlighted links between historic privilege and inequality of income and wealth (Allais, Citation2017). But inequality in the education system in South Africa is not exclusive to tertiary institutions, but exists in basic education and vocational training, too. This is compounded by the fact that South Africa has extremely high returns to tertiary education, leading to a cycle of privilege reinforcing inequality (see Bhorat et al., Citation2014; Cloete, Citation2016). In addition, there is evidence that tertiary education largely excludes the poor and very poor; over 80% of students who qualify to apply to study at degree level come from the top two income deciles (van den Berg, Citation2015). Conversely, those who are excluded from higher education are often restricted to low-paid, precarious jobs, and here there is a significant gender dimension: for example, two-thirds of South Africa’s 1.2 million domestic workers are women (Valodia & Francis, Citation2016). Understanding how education tackles or reinforces inequality is not straightforward and requires us to examine how race, class, and gender intersect.

As is evident above, researchers investigating poverty and inequality in South Africa have for many years had access to excellent poverty data, and data on income inequality. However, there has been very little written about the extent and dynamics of wealth inequality – a field of study that has attracted increasing attention since the seminal contribution on wealth inequality by Thomas Piketty (Piketty, Citation2014). A recent insightful paper by Orthofer (Citation2016) is the first significant investigation into wealth inequality in South Africa. The author used previously unpublished personal income tax data from the South African Revenue Service (SARS) for the 2010–11 tax year. Her results are striking, and underscore the importance of including an analysis of the distribution of wealth in any study of inequality. She found that while the highest-earning one percent of the population earns between 16–17% of all income, the top 10% earn 56–58%. Looking at wealth, however, the top 10% of the population own approximate 95% of all wealth, while 80% own no wealth at all (Orthofer, Citation2016). Not only are these findings striking, they show that the country has made little progress in addressing wealth inequality; in 1970, the richest 20% of the population owned 75% of all wealth (Wilson & Ramphele, Citation1994).

In 2013, the then finance minister, Pravin Gordhan, established the Davis Tax Committee with the overarching aim to examine the tax policy framework to assess how it could better support the objectives of inclusive growth, development, employment growth and fiscal sustainability. One of the most important and contentious options considered by the committee is the implementation of some form of wealth tax (Ensor, Citation2017). However, the Committee did not recommend the implementation of a wealth tax, arguing that much more work needed to be done to assess its feasibility and impact (Woolard et al., Citation2018). As highlighted above, there is a growing appreciation that inequality in wealth, around the world, and in South Africa, is significantly higher than inequality of income. But there is much more work to be done in understanding the dynamics of wealth inequality in South Africa.

5. Drivers of poverty and inequality

5.1. Macroeconomic context

South Africa is a relatively small and highly open economy, and so it is important to understand its location within the international macroeconomic landscape. One of the more important aspects to note is that, in terms of economic growth, South Africa is performing significantly worse than comparable countries, and even below the performance of the developed world. According to the 2018 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement, while developing countries grew at an annual average of 5.4% per year between 2010 and 2016, South Africa grew at only 2.1% per year. Looking ahead, developing countries are estimated to grow, on average, at 4.7% in 2018 and 2019, compared to 0.7 and 1.7% for South Africa in those respective years. While the accuracy of GDP as proxy for economic growth, and as a measure of economic wellbeing has rightly, in our opinion, been challenged, it is the most comparable indicator with which to assess South Africa’s economic performance in the global context.

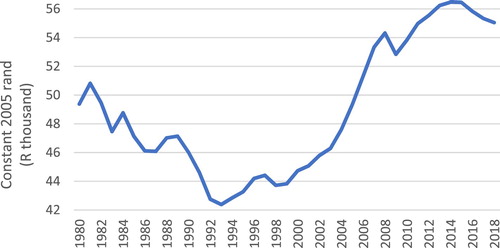

shows the per capita income trend for South Africa (in constant 2005 prices). As will be highlighted below, this indicator needs to be interpreted with caution due to the highly skewed income distribution in South Africa. Nevertheless, it provides a useful overview of income growth in South Africa. Most notable is decreasing per capita income between 2016 and 2017, and the continued forecasted reduction in per capita income into 2018.

Figure 1. South Africa’s per capita income. Source: (National Treasury, Citation2017).

In addition to declining per capital income, the post-financial crises period has seen markedly slower growth in tax revenue, and this has significant implications for South Africa’s redistributive fiscal policy, and will increasingly constrain budget space in the coming years (National Treasury, Citation2017). Recent media reports suggest that the receiver of revenue, the South African Revenue Service (SARS), could miss the tax revenue target for the 2017/18 tax year by as much as R50 billion, leading to the budget deficit climbing above the 3.4% of GDP predicted by March 2018 (Joffe, Citation2017).

5.2. The labour market

The labour market remains at the core of South Africa’s socio-economic challenges. In 1994, the narrow unemployment rate was 20%, rising to 26.7% in 2000 and falling to 22.5% by 2007 (International Labour Organisation, Citation2017). By 2017, however, the unemployment rate had risen to 27.7%, the highest level so far in the current decade (Statistics South Africa, Citation2017) (). Current political uncertainty and poor economic growth are predicted to drive the narrow unemployment rate even further, towards 30% in the coming years (Menon, Citation2017).

Table 3. Unemployment in South Africa.

The South African labour market can be characterised as a bifurcated one, where the high-skilled segment is dominated by excess demand, while the low-skilled tier is characterised by excess supply. There is a spatial aspect, too. Unemployment is very high in rural South Africa, due to a lack of economic opportunity in the former apartheid homelands (Bhorat et al., Citation2006).

In a recent report, the Development Policy Research Unit presented some important household-level indicators, drawn from the third wave of the nationally representative National Income Dynamics Survey (NIDS), from 2012 (Bhorat et al., Citation2016). The statistics are revealing. Only 15.9% of adults living in the poorest (quintile one) households are employed, compared to 75% in quintile five households. This results in a narrow unemployment rate for the poorest households of 61.2% compared to only 3.3% for quintile 5 households. As striking are the disparities in income: on average, then, the individuals in quintile five earn 39 times more than individuals in quintile one. Equally important is the finding that only one in three households in quintile one is categorised as a working household – meaning that it has at least one employed household member – compared to 87.8% of quintile five households (Bhorat et al., Citation2016).

As discussed above, wage income is the largest driver of overall income inequality in South Africa, but it is also a critical determinant of household poverty. Finn, (Citation2015) finds that 83% of households with no employed member fall below a poverty line of R1,319, compared to 50% of households with at least one earner. Access to employment is therefore a central issue in addressing both poverty and inequality. Like many developing countries, South Africa has witnessed a sustained decline in its primary sector – largely platinum, gold and coal mining – and a concomitant decline in employment. However, unlike many developing countries, South Africa has failed to grow its industrial base, and has seen a decline in manufacturing employment alongside its shrinking primary sector. As the so-called fourth industrial revolution takes hold, it is not clear how this long-term trend to rising unemployment can be reversed.

6. Combatting poverty and inequality

Debates continue as to the drivers of these indicators of socio-economic distress, with some arguing that we simply need higher growth and greater flexibility of employment. Others argue that deep structural reforms of the South African economy are required if we are to have any hope of achieving greater equality and lower levels of poverty and unemployment. These debates are linked in complex ways to the exercise of power by various actors and constituencies, both in and at a distance from the state, and their outcomes have material consequences for the people of South Africa. A new approach to overcoming inequality is required; one that systematically conducts research and engages in a policy dialogue which brings together the politics of inequality with the social and economic dimensions of the distribution of wealth, income and economic power. With this in mind we briefly review the key economic policies in post-apartheid South Africa.

6.1. A brief history of South Africa’s economic policy

Post-apartheid South Africa’s first wide-ranging economic policy was the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which was a significant part of the African National Congress’s 1994 election platform (South African History Online, Citation2017). The RDP soon became the new government’s mandate for reform, encompassing socio-economic programmes, institutional reform, educational and cultural programmes, and employment projects (Harsch, Citation2001). Under the RDP, there were significant shifts in expenditure away from the military, for example, and towards social spending such as housing, education and healthcare. This was accompanied by the RDP Fund, which financed high-profile presidential projects (Harsch, Citation2001). As a result, the RDP has been credited in some quarters with laying the foundation for South Africa’s extensive social security programme, which continues today.

The RDP was followed by the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) programme in 1996. The principal aims of the RDP, namely labour market reforms, productivity improvements and upskilling, were all contained in GEAR. However, in contrast to some of the main focus areas of the RDP, GEAR was explicitly a macroeconomic policy, which aimed to increase foreign investment and growth, and thereby stimulate job creation. According to Bhorat et al., Citation2006, ‘it was an export-led macroeconomic strategy that included “anti-inflationary policies, including fiscal restraint, continued tight monetary policies and wage restraint”’ (Bhorat et al., Citation2006:59–60). Despite ambitious GDP growth projections, in effect GDP per capita only grew at an annual average rate of 0.6% between 1996 and 2000, and unemployment grew steadily (Bhorat et al., Citation2006). In 2005, GEAR was replaced by the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa (ASGISA) which, had a slightly different focus to GEAR, with an emphasis on sustaining growth and broadening participation.

The National Development Plan was introduced in 2011, and was intended to be the long-term economic policy and strategy document for South Africa (South African History Online, Citation2017). The document, running to over 400 pages, notionally forms the basis of all economic policy in South Africa until 2030, and contains ambitious targets for social, economic and spatial transformation in South Africa (National Planning Commission, Citation2011). However, eight years after the official launch of the programme, there has been little in the way of meaningful implementation, and the country has fallen short on many of the key indicators, not least of all failing to meet the target of reducing unemployment to 20% by 2015, and falling far short of the GDP growth target of 5% per year. One of the main reasons for this was a global fallout from the financial crisis of 2008/09, which resulted in very low growth in South Africa in the years that followed. Furthermore, the NDP failed to achieve the support of all key constituents whose support would be critical to its success, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) being chief among these (Coleman, Citation2014).

In an important policy development, beginning in 2014, South Africa embarked on a process to investigate and then adopt a national minimum wage. The evidence presented by the advisory panel tasked with investigating the appropriate level for the minimum wage found that 47.3% of the 13,2 million workers in South Africa earned less than R3,500 per month for a full-time job in 2014. 91% of domestic workers and 85% of agriculture workers earned less than this amount (Valodia et al., Citation2016). The national minimum wage became a battle ground, serving as a proxy site for the diversity of economic ideologies that underpin policy making in South Africa. These debates are not limited to the national minimum wage itself as they point to the conception of the dynamics of the labour market, and highlight the tension between the liberal view that argues the solution to unemployment is to lower wages to the market-clearing level, and the structural view, which argues that there are significant non-wage impediments to full employment. In November 2016, the then Deputy President, Cyril Ramaphosa, announced that the national minimum wage would be set at R20 per hour, or R3,500 for a 40-hour work week. The national minimum wage came into force on 1 January 2019. The national minimum wage potentially raises the incomes of a significant proportion of the workforce. However, non-compliance with existing sectoral minimum wages can be as high as 50% (Runciman, Citation2017) and therefore, the institutional arrangements supporting the minimum wage are crucial. It is important that the new legislation is widely enforced, and that the workers have access to expedient recourse in the case of employer non-compliance. There are concerns, too, that the minimum wage will further exacerbate unemployment in the country, with commentators arguing that the solution to persistent unemployment is to lower wages, not raise them. However, the international evidence on the adoption of minimum wages suggests that, if the minimum wage is set at a reasonable level, the unemployment effects are not significant (Valodia et al., Citation2016). The impact of this important policy intervention on poverty and inequality in South Africa remains to be seen.

6.2. The constitution

A discussion of South Africa’s progress in addressing poverty and inequality is not possible without extensive reference to the South African Constitution, and its provisions for the advancement of socio-economic rights. The development of socio-economic policy in South Africa has been guided at all stages by the Constitution, and Constitutional litigation by civil society, and therefore understanding the role played by the Constitution is critical. A fundamental question is to what extent the liberal constitutional regime in South Africa enables or hinders the need for rapid and radical socio-economic transformation. This tension between an essentially liberal Constitution and the need for radical reform is highlighted by Michelman (Citation2013) when he asks the question:

Suppose we have three factors in play: a national project of post-colonial recovery from distributive injustice, prominently including land reform; express constitutional protection for property rights; and a Constitution whose other main features bring it recognisably within the broad historical tradition of liberal constitutionalism. Have we got a practical contradiction on our hands? … it may, even so, be true that the conditions of distributive justice within a national society will not always be achievable by means meeting the demands of an up-and-running liberal constitutional order. (Michelman, Citation2013:264)

Legal guarantees of political rights are indivisible from constitutional protection for social and economic rights. Without economic security and independence, individuals will be unable to realise individual freedom and express themselves freely in the social and political sphere. Without economic security and independence, culture and civil society cannot flourish. (Langa, Citation2013:460)

Most people in South Africa are poor, and most of the poor are women. It is no surprise that the achievement of equality, human dignity and freedom under South Africa’s Constitution is closely tied to the eradication of poverty and inequality. These goals are an essential part of South Africa’s transformative constitutional project, part of the wider constitutional commitment to ‘improve the quality of life and free the potential of all persons.’ Central to this transformative project, although often not recognised as such, is the need to address the distinctive forms of poverty and inequality experienced by women. (Albertyn, Citation2013:149)

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented a review of the main trends in poverty and inequality in South Africa during the post-apartheid era, and surfaced some of the differences and similarities between poverty studies and inequality studies. Despite early progress in reducing poverty, post-apartheid South Africa has seen rates of poverty and inequality increasing in recent years, with inequality now higher than it was at the end of apartheid. We have argued that South Africa’s inability to address either poverty or inequality is inextricably linked with policy stasis and enduring structural barriers that were entrenched during apartheid. We contend that there has been insufficient attention paid to the structures of economic, political and social power that continue to produce and reproduce poverty, and particularly inequality, in South Africa. The South Africa Constitution provides one example of a foundation for tackling poverty and inequality.

A central question, then, is why South Africa has made such poor progress in addressing poverty and inequality under such a progressive constitutional dispensation. One of the main reasons, perhaps, is a failure by the state to exert the kind of political power necessary to affect meaningful change. One reason for this is that a focus on the technical aspects of poverty and inequality – measurement and quantification, and temporal changes – has distracted us from directing our inquiry into how to effect change. The NDP is a striking recent example of the problems with implementing policy in South Africa. Indeed, it is a common refrain that South Africa doesn’t need good policy, it needs implementation. It is thus our view that addressing poverty and inequality requires us to think beyond technocratic policy solutions, and beyond a focus on measuring and quantifying inequality, and instead to the ways in which we can harness political, economic and social power for the good society. These forces of power must emerge through building a broad coalition of forces, both inside and outside the state, committed to overcoming the legacy of poverty and inequality in South Africa.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on an earlier version presented in Shanghai in November 2017 at a conference entitled: “No one left behind: Tackling poverty and inequality in Asia and around the world under the 2030 Agenda”. The conference and development of the paper was funded by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Shanghai.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

David Francis http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1494-9308

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Grzanka (Citation2014) and Lutz et al. (Citation2011).

2 Terreblanche’s research is rooted in a lively debate in the early seventies led by the so-called revisionists suggesting that capitalist development was reinforcing white supremacy (see Johnstone, Citation1970).

3 Boike Rehbein explores a similar issue using Bourdieu’s concept of habitas but gives primacy to class,

While social class becomes more important than race, skin colour still matters in South Africa because it is both associated with a habitus and assessed by a habitus shaped under Apartheid. “Race thinking” does not disappear overnight and the habitus takes generations to change. (Rehbein, Citation2018:12)

References

- Albertyn, C, 2013. Gendered transformation in South African jurisprudence: Poor women and the constitutional court. In S Liebenberg & G Quinot (Eds.), Law and poverty: Perspectives from South Africa and beyond. Juta, Cape Town, 149–71.

- Allais, S, 2017. Towards measuring the economic value of higher education: Lessons from South Africa. Comparative Education 53(1), 147–63. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2017.1254985

- Bhorat, H, Caetano, T, Jourdan, B, Kanbur, R, Rooney, C, Stanwix, B & Woolard, I, 2016. Investigating the feasibility of a national minimum wage for South Africa. http://www.ilo.org/ilostat/faces/oracle/webcenter/portalapp/pagehierarchy/Page3.jspx?MBI_ID=2&_afrLoop=4957141712613&_afrWindowMode=0&_afrWindowId=loeqoumvd_1#!%40%40%3F_afrWindowId%3Dloeqoumvd_1%26_afrLoop%3D4957141712613%26MBI_ID%3D2%26_afrWindowMode%3D0%26_adf.ctrl-state%3Dloeqoumvd_33 Accessed 15 September 2017.

- Bhorat, H, Cassim, A & Tseng, D, 2014. Higher education, employment and economics growth: Exploring the interactions. Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Bhorat, H, Kanbur, SMR & Human Sciences Research Council (Eds.), 2006. Poverty and policy in post-apartheid South Africa. Human Sciences Research Council Press, Cape Town.

- Cloete, N, 2016. Free higher education: Another self-destructive South African policy. Centre for Higher Education Trust, Cape Town. https://chet.org.za/files/Higher%20education%20and%20Self%20destructive%20policies%2030%20Jan%2016.pdf Accessed 9 September 2017.

- Coleman, N, 2014. NDP: Doomed from the outset. The Daily Maverick, 30 July. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2014-07-30-ndp-doomed-from-the-outset/#.WgATjBNL80o Accessed 10 September 2017.

- Ensor, L, 2017. Davis committee to mull wealth tax. The Business Day, 25 April. https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/economy/2017-04-25-davis-committee-to-mull-wealth-tax/. Accessed 10 September 2017.

- Finn, A, 2015. A national minimum wage in the context of the South African labour market. http://nationalminimumwage.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/NMW-RI-Descriptive-Statistics-Final.pdf. Accessed 10 September 2017.

- Finn, A & Leibbrandt, M, 2017. The dynamics of poverty in South Africa (Working Paper No. 174). SALDRU, Cape Town.

- Glaser, D, 2017. National democratic revolutions meets constitutional democracy. In E Webster & K Pampallis (Eds.), The unresolved national question: Left thought under apartheid. Wits University Press, Johannesburg, 274–96.

- Grzanka, PR (Ed.), 2014. Intersectionality: A foundations and frontiers reader. Westview Press, a member of the Perseus Books Group, Boulder, CO.

- Harsch, E, 2001. South Africa tackles social inequities. Africa Recovery 14(4), 12–8.

- Hundenborn, J, Leibbrandt, M & Woolard, I, 2016. Drivers of inequality in South Africa (Working Paper No. 194). SALDRU, Cape Town.

- International Labour Organisation, 2017. ILOSTAT. http://www.ilo.org/ilostat/faces/oracle/webcenter/portalapp/pagehierarchy/Page3.jspx?MBI_ID=2&_afrLoop=4957141712613&_afrWindowMode=0&_afrWindowId=loeqoumvd_1#!%40%40%3F_afrWindowId%3Dloeqoumvd_1%26_afrLoop%3D4957141712613%26MBI_ID%3D2%26_afrWindowMode%3D0%26_adf.ctrl-state%3Dloeqoumvd_33. Accessed 1 October 2017.

- Joffe, H, 2017. Downgrade alarm as revenue shortfall could hit R50bn. The Business Day, 30 October. https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/economy/2017-08-21-downgrade-alarm-as-revenue-shortfall-could-hit-r50bn/. Accessed 5 November 2017.

- Johnstone, F, 1970. White prosperity and white supremacy in South Africa today. African Affairs 69(275), 124–40. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a095990

- Langa, P, 2013. The role of the constitution in the struggle against poverty. In S Liebenberg & G Quinot (Eds.), Law and poverty: Perspectives from South Africa and beyond. Juta, Cape Town, 4–9.

- Leibbrandt, M, Finn, A & Woolard, I, 2012. Describing and decomposing post-apartheid income inequality in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 29(1), 19–34. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2012.645639

- Lipton, M, 1986. Capitalism and apartheid: South Africa, 1910-1986. . Wildwood House, Aldershot, Hants, England.

- Lutz, H, Herrera Vivar, MT & Supik, L (Eds.), 2011. Framing intersectionality: Debates on a multi-faceted concept in gender studies. Farnham; Ashgate, Burlington, VT.

- Menon, S, 2017. Economists warn SA’s unemployment likely to soar. The Business Day, 1 November. https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/economy/2017-11-01-economists-warn-sas-unemployment-likely-to-soar/. Accessed 4 March 2018.

- Michelman, F, 2013. Lineral constitutionalism, property rights, and the assult on poverty. In S Liebenberg & G Quinot (Eds.), Law and poverty: Perspectives from South Africa and beyond. Juta, Cape Town, 264–81.

- National Planning Commission, 2011. National development plan: Vision for 2030. The National Planning Commission, Pretoria, South Africa.

- National Treasury, 2017. Medium term budget policy statement. http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/MTBPS/2017/mtbps/FullMTBPS.pdf. Accessed 1 November 2017.

- Nattrass, N & Seekings, J, 2013. Job destruction in the South African clothing industry: How an unholy alliance of organised labour, the state and some firms is undermining labour-intensive growth. Centre for Social Science Research, Cape Town.

- Nattrass, N & Seekings, J, 2019. Inclusive dualism: Labour-intensive development, decent work, and surplus labour in Southern Africa. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

- Nicolson, G, 2018. Trade misinvoicing costs South Africa $7.4bn in tax a year. The Daily Maverick, 19 November. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-11-19-trade-misinvoicing-costs-south-africa-7-4bn-in-tax-a-year/. Accessed 20 April 2019.

- Orthofer, A, 2016. Wealth inequality in South Africa: Evidence from survey and tax data. http://www.redi3x3.org/sites/default/files/Orthofer%202016%20REDI3x3%20Working%20Paper%2015%20-%20Wealth%20inequality.pdf. Accessed 15 September 2017.

- Piketty, T, 2014. Capital in the twenty-first century (A. Goldhammer, Trans.). The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Rehbein, B, 2018. Social classes, habitus and sociocultures in South Africa. Transcience 9(1), 1–19.

- Runciman, C, 2017. Why changes to South Africa’s labour laws are an assault on worker’s rights. Mail and Guardian, 13 December. https://mg.co.za/article/2017-12-13-why-changes-to-south-africas-labour-laws-are-an-assault-on-workers-rights. Accessed 15 September 2018.

- Seekings, J & Nattrass, N, 2005. Class, race, and inequality in South Africa. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Sen, A, 1993. Capability and well-being. In M Nussbaum & A Sen (Eds.), The quality of life. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 30–53.

- Soudien, C, Reddy, V & Woolard, I, 2019. Poverty and inequality in South Africa: The state of the discussion in 2018. In C Soudien, V Reddy & I Woolard (Eds.), Poverty & inequality: Diagnosis prognosis responses: State of the nation. HSRC Press, Pretoria, South Africa, 1–41.

- South African History Online, 2017. South Africa—First 20 years of democracy: Key economic policy changes 1994-2013. http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/south-africa%E2%80%99s-key-economic-policies-changes-1994-2013 Accessed 13 March 2018.

- Statistics South Africa, 2017. Poverty trends in South Africa, No. 03-10–06. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria.

- Terreblanche, SJ, 1997. Testimony before the T.R.C during the special hearing on the role of the business sector. Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

- Terreblanche, SJ, 2002. A history of inequality in South Africa, 1652-2002. University of Natal Press; KMM Review Pub, Pietermaritzburg, Sandton, South Africa.

- Therborn, G, 2013. The killing fields of inequality. Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Valodia, I, Collier, D, Cawe, A, Lijane, M, Koyana, S, Leibbrandt, M & Francis, D, 2016. A national minimum wage for South Africa. http://new.nedlac.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/NMW-Report-Draft-CoP-FINAL1.pdf. Accessed 7 September 2017.

- Valodia, I & Francis, D, 2016. How the search for a national minimum wage laid bare South Africa’s faultlines. The Conversation, 28 November. https://theconversation.com/how-the-search-for-a-national-minimum-wage-laid-bare-south-africas-faultlines-69382. Accessed 10 September 2017.

- van den Berg, S, 2015. Funding university studies: Who benefits? (No. 10). Council for Higher Education, Pretoria.

- Van der Horst, ST, 1976. The Theron Commission report: A summary of the findings and recommendations of the Commission of Enquiry into Matters Relating to the Coloured Population Group. http://books.google.com/books?id=wm50AAAAMAAJ. Accessed 10 July 2019.

- Wilson, F & Ramphele, M, 1994. Uprooting poverty: The South African challenge (Fourth Impression). David Philip, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

- Wittenberg, M, 2017. Are we measuring poverty and inequality correctly? Comparing earning using tax and survey data. http://www.econ3x3.org/sites/default/files/articles/Wittenberg%202017%20Comparing%20tax%20and%20survey%20earnings%20data%20-%20FINAL.pdf Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Woolard, I, Lester, M, Davis, D, Oguttu, D, Padia, N, Ajam, T & Legwaila, T, 2018. Feasibility of a wealth tax in South Africa [Report to the Minister of Finance]. http://www.sataxguide.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/20180329-Final-DTC-Wealth-Tax-Report-To-Minister.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2019.

- World Bank, 2014. South African economic update: Fiscal policy and redistribution in an unequal society (No. 92167). The World Bank Group, Washington, DC.