ABSTRACT

From the moment South Africa became a liberal democracy, the Government promised to deliver on social security for the poor. However, South African NGOs have reported that several barriers prevent poor South Africans, and black women in particular, from accessing the country’s social assistance system. Government inaction has compelled NGOs to approach the Courts. As reflected in a series of court judgements, many problems faced by the system relate to the administration of payments by South African and multinational corporations. But is this the complete story?

Applying a critical, analytical lens of legal mobilisation to explain the potential of legal mobilisation to secure progressive structural change, this article will assess the extent to which civic-based, legal advocacy aimed at securing access to social grants, and challenging the manner in which these grants have been administered, has the potential to more strategically advance socioeconomic justice and inequality for South Africa’s poor.

1. Introduction

South Africa became a liberal democracy in 1994, with a government that promised to deliver on ensuring social security for the poor (Goldblatt, Citation2014:24). Between 1994 and 2016, social security in the form of cash transfers increased, particularly for the bottom 40 percent of South Africa’s income distribution, leading the World Bank to observe that ‘the grant system [has] helped reduce poverty, stabilise the annual growth of real earnings, and increase employment and labour force participation among women’ (Bruni, Citation2016:119). The World Bank further remarked that ‘a combination of commitment, leadership, backing from the Constitution, focus on technical soundness, broad countrywide dialogue, and engagement with civil society contributed to this success’ (Ibid: 120).

However, a number of structural barriers still prevent many poor South Africans, and black women in particular from accessing the grant system (Goldblatt, Citation2014). In particular, the broader administration of social assistance, in which social grants have been a core feature, has been fraught with challenges. This includes a lack of integration between cash transfers and social services, onerous grant application procedures (particularly regarding grants for foster-care), allegations of fraud and out-sourcing payments to private corporations (Bruni, Citation2016). Moreover, social grants are targeted and have from their inception tended to exclude the most vulnerable, and in particular the long-term unemployed (van der Berg, Citation1997).

In an effort to address the administrative barriers to accessing social grants, civil society organisations initiated strategic litigation as their principle, law-based advocacy strategy between 2010 and 2017. However, the benefits of strategic litigation alone are deserving of critique. The courts have concluded that many problems faced by the social grants system relate to the administration of payments by South African and multinational corporations. But is this the complete story? And to what extent can litigation alone address the country’s broader structural inequalities?

An analytical lens of legal mobilisation can explain both the strategic potential and limitations of litigation alone to secure progressive structural change by way of legal transformation, including access to social grants as part and parcel of an internationally-recognised human right to social security. The multi-dimensional legal mobilisation lens that we apply in this paper reveals the extent to which the courts are able to deliver socio-economic justice as well as the nuanced manner in which inequalities are perpetuated and reinforced.

Accordingly, we argue that while the courts in South Africa were able to exercise some judicial oversight when the state – especially members of the executive – failed to adequately promote or protect socio-economic rights, the courts have been unable to tackle broader structural exclusion and inequalities of race, gender and class. This reveals limits to the potential of litigation as a tool for transformative, socio-economic reform.

In the first part of this article, we will provide a brief introduction to the case study of litigation around access to social grants in South Africa. The legal mobilisation lens will then be introduced, followed by an application of this lens to the case study of litigation brought by the Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) Black Sash in 2013, together with the Legal Resources Centre (LRC), a legal services NGO and others. We explain how litigation and other forms of law-based advocacy have increased public awareness on socio-economic rights issues, and compelled government to improve its administrative procedures. Second, we argue that while bringing matters to the courts has been symbolically useful, the results on the ground have been limited. We then explain how government officials have seldom been held individually accountable for maladministration. We conclude that civic-based, legal advocacy aimed at securing social assistance, and at challenging the manner in which it has been administered, has the potential to be reconfigured and broadened in order to more meaningfully advance socioeconomic justice for South Africa’s poor.

2. Litigating the right to social assistance

Efforts by South African NGOs to access social assistance through the Courts initially took a very indirect route. Following a successful bid by a private company, Cash Paymaster Services (CPS) to distribute social grants following a government-tender process, a competing company – All-Pay – took legal action to challenge this, alleging serious improprieties in the government-tendering process. Having lost the bidding process to CPS; AllPay’s primary purpose was to claim remedial damages for corporate losses. The case went all the way to the Constitutional Court.

In an unexpected turn of events, the Constitutional Court admitted two NGOs to the litigation, namely Corruption Watch and the Centre for Child Law as so-called amicus curiae or friends of the Court. From an evidentiary standpoint, Corruption Watch was able to demonstrate that deviations from fair procedural requirements by public officials were symptomatic of corruption; the corporate litigants remained silent on this matter. Meanwhile, the Centre for Child Law highlighted the need to protect child grant beneficiaries, building a stronger case for Court oversight over the administration of social grant payments (AllPay, Citation2013; Corruption Watch, Citation2013).

In 2013 and 2014, following legal interventions by Black Sash and the LRC in the All-Pay litigation, the Constitutional Court came back with a judgement that at first sight appeared to be favourable to these NGOs. The tender process initiated by the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) in 2012 to administer the payments of social grants nationally through CPS for a period of five years was declared by the Court to be invalid and was set aside. When the CPS contract was due to end on 30 September 2018, SASSA, together with the South African Postal Service, was eventually designated to take over the distribution of payments (VvG, Citation2018).

An earlier court had already concluded that the SASSA was obliged to re-initiate the tender process and ensure, moreover, that the government should have adequate capacity to ultimately take over the payment process itself. Noting that the government would not meet the April 2017 deadline, the court then gave the government an additional year to put together the arrangements. Later, when it became clear that there had been little progress, the Constitutional Court publicly reprimanded the Minister of Social Development, Bathabile Dlamini, for inadequate planning (Black Sash, Citation2018c). This led to calls for Dlamini’s dismissal, although the Government instead redeployed her to another Ministerial function within the Office of the Presidency (Marrian, Citation2017; Davis, Citation2018).

For some time following the litigation originally initiated by All-Pay, civil society organisations in South Africa, and in particular Black Sash and Corruption Watch, continually voiced their concern that the future of the social grant payment system was unclear, compromising the State’s obligation to realise the right to social security through a properly administered system of social grants (GroundUp, Citation2017). In March 2018, SASSA requested yet another extension from the Constitutional Court to the CPS contract (Chabalala, Citation2018). This extension too was challenged by the NGOs.

The decision to intervene in what was essentially a corporate dispute between All-Pay, the government and CPS, rather than to initiate separate litigation itself to address the deeper problems with the social assistance system was a curious decision by the NGOs. This case nevertheless provided a unique opportunity to both recognise the legal standing of NGOs, and to clarify the broader circumstances under which social grants were administered that were highly-unlikely to have been raised by All-Pay. Accordingly, we analyse these strategic litigation efforts using an analytical lens of legal mobilisation.

3. A legal mobilisation lens

An analytical lens of legal mobilisation can explain how the functional (socio-legal) dimensions of interacting with the law as part of a social justice claim can be productively combined with a legal-philosophical approach based on legal pragmatism. In this regard, we share Taekema’s perspective that ‘does not reduce law to an instrument to advance social goals (but) sees law as both a means and an end in itself’. Accordingly, law is both a theory and ‘a practice which is characterised by a commitment to certain specifically legal ideals’ (Taekema, Citation2006:35). As with any law-based social justice claim, there is an inter-relationship, though often a large gap as well, between the aspirations of law and its implementation, which requires some form of intervention.

This section builds on research by Handmaker (Citation2019), developing legal mobilisation both as an analytical concept, namely the legitimate use of law to underpin political claims, and as an analytical lens to evaluate law-based advocacy, including but not limited to strategic interest litigation.

3.1. Conceptualising legal mobilisation as a legitimate political claim

Legal mobilisation involves the strategic use of law by civic actors to advance human rights as both a legitimate legal claim as well as a political claim. Legal mobilisation, including the pursuit of human rights and justice through the courts, is never a straightforward activity; it is regarded, more often by social scientists, and even by some lawyers, as a highly political act (Abel, Citation1995; Gready, Citation2004; De Feyter et al., Citation2011). As Abel’s, Citation1995 study of anti-apartheid legal struggles in South Africa has vividly illustrated, law is a form of politics by other means. Accordingly, law can be effectively wielded as a shield, for example in order to protect individuals from abuse by the state, or as a sword, by oppressive regimes against perceived enemies of the state. Law may also be wielded as a sword by civic actors in the form of proactive claims to seek redress for injustice and/or inequalities.

Legal mobilisation as a practice involves direct or indirect challenges to a state or its agents who are alleged to be responsible for human rights violations, involving multi-layered interactions between the alleged victims and perpetrators of these violations. However, understanding legal mobilisation as a legitimate means of claiming rights on its own doesn’t go far enough to explain the potential or challenges of formulating law-based advocacy.

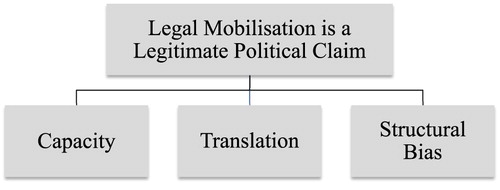

To focus on the structural factors that confront human rights advocates, and study the interplay between civic actors engaged in legal mobilisation, and the state institutions, or its agents, against whom the mobilisation is aimed, we present three theory-based propositions, as illustrated in . The first proposition is that civic actors have legally-mandated capacity to challenge the state, which enhances their legitimacy to mobilise (international) law, derived from normative developments in human rights. While the legal capacity of civic actors to bring claims is largely uncontested – although the space for bringing these claims is arguably shrinking – the political legitimacy that this legality confers is crucial in order to counter claims that advocates are abusing legal process. The second proposition is that civic actors engaged in legal mobilisation translate global rules into a locally relevant context (i.e. more than merely taking legal measures). The third proposition is that international law’s inherent structural bias truly matters in explaining the strategic potential for law-based advocacy, both in terms of the institutions against which legal mobilisation is directed as well as the substantive law that forms the basis of legal claims.

3.2. Civic actors have the capacity to challenge the state

The legal capacity of civic actors to promote and, in limited circumstances, impose state accountability for meeting national and international legal obligations through legal mobilisation has been shaped by structural changes in international normative frameworks and by associated political developments.

This capacity of civic actors has emerged in what Ignatieff has termed a global human rights revolution, with juridical, advocacy and enforcement dimensions, though of a distinctly liberal nature (Ignatieff, Citation1999; Ignatieff & Gutmann, Citation2001). The liberal character of this ‘revolution’ is problematic for three reasons that can be attributed to the ideological bias embedded in liberal systems of governance. First, there has been a gradual retreat of the state from actively fulfilling its human rights violations, leaving the primary responsibility for enforcing rights claims to individuals (Handmaker & Arts, Citation2018:4, 7). Second, liberal governance systems are inherently reluctant to hold business accountable in what has been characterised as the ‘post-regulatory state’ (Scott, Citation2004:145). Finally, Mutua (Citation2013) addressing social justice problems in a liberal system of governance has produced both a human rights movement and corpus that contain a range of attendant, but largely unacknowledged biases, most notably a Eurocentric orientation. In South Africa especially, all three problems are highly visible, leading Modiri (Citation2018:295) in his contribution to a Special Issue on this topic to argue that the liberal constitutional tradition is itself very much ‘an object of critical interrogation’.

These liberal biases notwithstanding, developments in the human rights field have broken new ground for social-justice advocates, extending the normative scope of human rights law to address a wide range of social justice issues (Donnelly, Citation2003; Higgins, Citation1994). Such normative developments have been matched by a corresponding increase in civic participation, and expanded use of accountability mechanisms in human rights advocacy (Risse et al., Citation1999; Korey, Citation1998). Civic actors are, consequently, active participants in international and national legal processes, and who have skilfully combined litigation with other forms of civic mobilisation, including interactions with the media, traditional sources of authority and global solidarity networks.

Civic participation in legal process, and particularly the ability of civic actors to invoke national and international law and institutions, has profoundly shifted the civic-state relationship, though by no means replaced it. The liberal democratic state and its institutions remain significant, not least when one is navigating the possibilities of translating human rights for social justice claims, where power relations are very often obscured by the close, though often nebulous relationship between government and business (Nattrass & Seekings, Citation2010).

3.3. Civic actors can be translators

Drawing on their legal capacity to challenge the state, civic actors that are engaged in legal mobilisation fulfil a crucial mediating role in the translation of international legal norms into local contexts. Translation is more than merely transplanting the content of a global legal role into a national legal system; it requires engagement with the local-cultural context where either human rights obligations are not being fulfilled, or where a remedy to make a rights-based claim is sought. While translation can happen without the intervention of translators, those actively seeking to accomplish translation possess what Merry conceptualises as a double consciousness of the content of international law and the circumstances in which it is framed and enforced at the international level, as well as the grounded local cultural context in which these international norms find expression (Merry, Citation2006; Goodale & Merry, Citation2007). By the same token, it does not mean that those who are unfamiliar with international law and institutions are not in a position to bring a claim against the government, but they may frame their claim differently.

Legal consciousness is a socio-legal concept, something that can be measured. It is more than merely an aptitude, competence or awareness of the law, but also relates to perceptions and images associated with the law and legal enforcement (Hertogh, Citation2004:461). As Ewick & Silbey (Citation1998) have argued, this includes a instrumentalist/pragmatic view of the law, regarding it as a game.

It is important to explore people’s imagination and expectations of the law as against the views of professional lawyers who tend to ‘ignore’ this (Hertogh, Citation2004:459). This entails two analytical approaches. The first approach asks: how do people experience official law or what is referred to by various authors as law in action. Such an approach can reveal a ‘persistent contradiction’ between the ideal (values) behind law and the actual (values) embedded in a particular action (Ibid: 475; Merry, Citation1990; Ewick & Silbey, Citation1998; Nielsen, Citation2004). The second approach asks what do people experience as law or what is commonly referred to as the ‘living law’, focussing more on the people and their own norms, studying the problem and how international law is invoked to address it from below (Hertogh, Citation2004:475; Ehrlich, Citation1936; Rajagopal, Citation2003). This approach can reveal a ‘personalistic value orientation’ that places a ‘strong emphasis on the special circumstances of each individual citizen’, whereby legitimacy is based not on official, state-published legal definitions, but on the extent to which public officials feel a close affinity for the local community (Ibid: 477–478). Drawing on these approaches, legal translation focuses on the social processes of giving effect to human rights obligations (Merry, Citation2006:39). This may, or may not include an explicit engagement with the structural bias contained in international law.

3.4. Structural bias of international law

Beyond framing social justice claims in terms of human rights, legal mobilisers may engage in a more complex engagement with the structural bias contained in both substantive law and institutional structures, which heavily condition civic efforts to hold states accountable to international human rights norms and tends to favour elite interests. Law reflects particular values (certainty, predictability, universality), and is accompanied by regulatory institutions that are in many cases relics of earlier regimes in which most of the world was colonised. Accordingly, the third component of a legal mobilisation framework applies Koskenniemi’s (Citation2009:9) concept of structural bias in global governance, referring to ‘the way in which patterns of fixed preference are formed and operate inside international institutions’.

Koskenniemi (Ibid: 9–12) argues that structural bias is a consequence of international law’s fragmentation, meaning that international law has evolved into ‘a wide variety of specialist vocabularies and institutions’. This includes humanitarian law and human rights, which are some of the more recent, and contested of these vocabularies. On the one hand, it is possible to mobilise these vocabularies, adding legal legitimacy to a claim by framing it in the language of these international legal vocabularies (Handmaker & Arts, Citation2018:16). On the other hand, the rhetoric of rights is said to have lost its ‘transformative effect’ through over-legalistic explanations and is ‘not as powerful as it claims to be’ (Koskenniemi, Citation2011:133).

The structural bias of law is also prevalent at the national level, which Galanter (Citation1974) has observed tends to predictably favour elite sections of society, categorised as repeat players who make frequent use of the legal system (and particularly litigation) in order to shape the law and secure their interests. Like corporate entities, NGOs are also often linked to these elite sections of society, both as sources of financing and through other, social networks (Mutua, Citation2001).

Alongside political legitimacy, this three-dimensional lens forms an analytical basis for assessing the potential of legal mobilisation to lead to social transformation. Returning to our main argument, we now apply this lens to the struggle for social assistance in South Africa.

4. Analysing the struggle for social grants in South Africa through legal mobilisation

As noted earlier, NGOs joined a corporate dispute over the outcome of a government tender in order to raise attention to and trigger a broader debate regarding the distribution of social grants in South Africa. While bringing the matter to the courts raised public awareness through the media on socio-economic rights issues, members of the government were never held personally accountable for maladministration, including their role in questionable tender processes and wasteful resource expenditure by their political superiors. This is in spite of repeated court pronouncements on the personal conduct of the Minister in stalling planning processes. Consequently, citizens affected by failings associated with social grants have questioned the effectiveness of South Africa’s constitutional framework and the rule of law (Pityana, Citation2017).

Beyond individual accountability for government mis-management, the litigation also drew renewed attention to the questionable role of private companies becoming involved in key government functions to the point of state ‘capture’. In this case, CPS and its holding company (Net1) were found to have violated the legal right to privacy of grant beneficiaries through distributing its data for the purposes of marketing largely financial goods and services of third-party contractors (Black Sash, Citation2018c).

However pertinent such matters are to the failings of social grants as part of a broader social assistance system, there were deeper, structural issues at stake that Black Sash and other NGOs wished to address through strategic litigation. The extent to which litigation successfully addressed these deeper issues can be analysed through our legal mobilisation lens.

4.1. Securing social assistance as a legitimate political claim

South Africa has a rich history of claiming constitutionally protected socio-economic rights for historically marginalised groups through the courts. Civic actors have, since the 1980s, persistently sought redress for historical injustices framed by persistent inequalities of gender and race (Abel, Citation1995). Originally forged during the anti-apartheid struggle, the legally-supported political claims brought from the late 1990s mirror these earlier litigation strategies. They have been brought forward by South African NGOs, social movements and others in the post-1994 period of liberal democracy in South Africa and have often been framed in terms of a broader critique of globalisation. They have been regarded as a legitimate ‘counterbalance’ to try and promote the concerns of the poor and elevate these concerns to the political agenda (Ballard et al., Citation2005).

The courts have been slow to regard inequality as impeding access to constitutionally guaranteed civil, political and socio-economic rights. Moreover, the intersectional implications of vertical inequality, represented by wealth and income, with other forms of horizontal inequality, such as the power dynamics that arise from one’s gender, race or class, have been largely unaddressed by the courts, and associated institutional reform has also been limited. Beyond expanding the content of socio-economic rights, the courts have been hesitant to prescribe how the legislature and executive ought to go about realising constitutional obligations and have refused to recognise a minimum core of obligations. For example, in the case of Mazibuko (Citation2009), the Constitutional Court debated, but ultimately rejected the notion of a minimum core of essential rights as prescribed by international human rights treaty bodies (Bilchitz, Citation2003; Young, Citation2008). The minimum core approach has been criticised for being inflexible, placing undue pressure on the State to meet the diverse needs of people who are poor (Wesson, Citation2004). Instead, the Courts have negotiated a ‘delicate balance’ (Klaaren, Citation2006) between court-sanctioned interventions and government decision-making through a cautious interpretation of ‘reasonableness’ (Hoexter, Citation2006).

These limitations notwithstanding, socio-economic rights litigation has allowed civic actors to assert some political claims, seeking to shape the trajectory of the South African political economy. Although centred on human rights violations, this litigation has also highlighted maladministration as perpetuating and reinforcing structural discrimination that is experienced daily by historically marginalised groups. In 2011, the year in which the tender process for social grant administration commenced, then President Zuma claimed that the government could not afford to indefinitely provide social grants as a welfare state, but should rather focus on developing equal opportunities and reduce the number of grant beneficiaries. He added that the state could not continue paying for the failures of the apartheid administration, and that taxpayers should develop the country ‘rather than feed the poor’ (City Press, Citation2011).

While civil society organisations have attempted to dispel the myth that social grants entrench laziness and dependency on the state by its beneficiaries, the legitimacy of their law-based political claim has been enhanced by framing it as a constitutional right of beneficiaries (Ferreira, Citation2017). Furthermore, the process of reviewing the government’s actions through the courts exposed an intricate relationship between the state and the private sector, as well as the covert ways in which the private sector has continued to profit from the structural exclusion and social inequalities experienced by historically marginalised groups (Du Toit, Citation2017).

Beyond reinforcing the legitimacy of the claim to secure social assistance, we apply our legal mobilisation lens to take a deeper look at how the specific cases that were brought in relation to social grants strengthened the potential for social transformation. The first element of this is the capacity that civic actors had to bring a claim to social assistance in the first place.

4.2. Asserting the capacity to litigate access to social grants

The capacity of individuals and groups to bring a socio-economic rights claim, or the so-called ‘justiciability’ of these rights, including the right to social security through social assistance, has been contested since the country’s constitutional negotiations of the early 1990s. The court’s handling of socio-economic cases too has been mixed. Strategic litigation on socio-economic rights initiated by civil society organisations has revealed both the inseparable relationship between civil and political and socio-economic rights and the nuanced manner in which structural inequality manifests and is reinforced. Strategic litigation has also affirmed how important it is to involve broader social groups to realise the potential of socio-economic rights, including conceptualising structural change as an indicator for how such rights can be progressively realised (Langford et. al. Citation2014).

The very first case brought before the Constitutional Court with respect to the administration of the social grants system revealed a low threshold of capacity and – as mentioned – was not initially brought by NGOs (AllPay, Citation2013). The case was indeed not originally concerned with the right as such to social security, but with maladministration within the grant system, particularly after state responsibilities had been outsourced to private companies. By admitting the NGOs to the litigation, the Court crucially recognised both the legal capacity of the NGOs and the human rights implications of corporate actions.

Recognition of legal capacity was further extended in subsequent litigation, through grassroots mobilisation involving not only Black Sash, the Centre for Child Law and the Legal Resources Centre, but also the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS), an action-research Institute based at Wits University. Together, these NGOs exposed the extent to which Net1, CPS’ holding company, continued to benefit from wilful maladministration.

Beyond analysing how legal capacity had been exercised, we now analyse the extent to which NGOs litigating access to social grants have served as legal translators of human rights.

4.3. Black Sash as translators

As an approach, legal translation can reveal how South African NGOs mediate their relationship between internationally-prescribed human rights to social security and the locally-relevant circumstances in which access to social grants is an imperative. Like other NGOs with a nationwide network of advice offices, Black Sash had decades of human rights and social justice activism and grassroots knowledge of social justice issues that informed its national and international advocacy. The organisation also had extensive experience in advocating for the advancement of human rights through the United Nations, as well as the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Accordingly, as a longstanding, locally-grounded, internationally-engaged advocate, Black Sash has played an important role both in the anti-apartheid movement and in addressing racism and inequality generally.

From the late 1990s, Black Sash focussed its advocacy on social grants and social protection, poverty reduction and inequality, through citizen-based monitoring of human rights violations, human rights education and training. The organisation has made frequent reference to international law and the circumstances in which it is framed and enforced, as well as displaying a grounded understanding of the relevant local and national context in which international human rights find expression. According to Merry’s (Citation2006) conceptualisation of a double consciousness, the organisation was well-situated to operate as a legal translator and to frame a nuanced response to rights realisation.

This was vividly illustrated in 2011 when, based on reports from its advice offices, the organisation was alerted to electronic debit deductions from social grant beneficiaries’ bank accounts. Black Sash had earlier met with representatives of SASSA to discuss the unauthorised deductions, expressing concern that the tender agreement with the identified service provider (CPS) allowed for the advancement of for-profit micro-loans to grant beneficiaries. Through its Hands Off Our Grants (HOOG) campaign launched in 2012 and implemented though community advice offices throughout South Africa, Black Sash (Citation2018a), grant beneficiaries were advised by Black Sash regarding lawful and unlawful deductions from their social grants accounts. A core component of the campaign was to gather evidence not only of debit deductions from SASSA beneficiaries for items that were deemed as ‘luxury’ items, but also for many loans made by micro-lenders affiliated to Net1 and CPS for essential items that were unauthorised and unlawful, using social grants as collateral. In 2013, the Black Sash and its legal representatives again met with SASSA, wherein SASSA committed to addressing these concerns and to attend to the relevant loopholes in the tender agreement with Net1. Black Sash also engaged with the Reserve Bank of South Africa and the Department of Social Development (DSD) requesting intervention to prevent subsequent deductions, resulting in the establishment of a Ministerial Task Team to explore ways to stop the deductions (Black Sash, Citation2018b). Black Sash’s data from its advice offices exposed these practices that trapped South Africa’s most vulnerable communities into a cycle of poverty and debt.

After Black Sash and other NGOs established that micro-lenders were not selling loans for luxury items, but rather for essential services, the Constitutional Court ordered the State to ensure that personal data of grant beneficiaries be sufficiently safeguarded, and not be used for any purpose other than the payment of social grants (Black Sash, Citation2018c). Framing the relevance of their claim in terms of international human rights, it was argued in court that:

Article 9 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights provides that ‘The States Parties to the present Covenant recognise the right of everyone to social security, including social insurance.’ In the implementation of its obligations … South Africa is obliged to use ‘all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures’ in taking whatever steps are necessary to ensure that everyone enjoys the right to social security. As a matter of logic, enjoyment of the right requires protection against the depletion of the social assistance which is provided (Black Sash, Citation2017a).

From a legal consciousness standpoint, Black Sash framed their complaint by emphasising ‘the special circumstances of each individual citizen’, whereby the claim was based not on official, state-published legal definitions, but on the extent to which public officials lacked an affinity for the social security needs of South African citizens (Hertogh, Citation2004:477–478). The argument put forward to the Court of Appeal emphasised how out of touch public officials were with the needs and concerns of South African citizens, revealing a ‘persistent contradiction’ between the rules and values that underpinned proper government behaviour, and the actual values embedded in the actions of Net1 (Ibid: 475).

Frequent, and contextually-grounded references by NGOs to international law and to the nuanced circumstances of SASSA and Net 1’s actions in Court documents, in public statements and in awareness campaigns revealed NGOs’ roles as legal translators. However, given the volatile politics surrounding the claim, stronger action was arguably needed. This compels us to examine the extent to which full use has been made of international law’s structural bias to leverage additional external pressure on the government to meet its international obligations.

4.4. Leveraging the structural bias regarding access to social assistance

While some reference was made to international human rights, references to international law by NGOs in litigating access to social assistance through targeted grants has been fairly limited. The fact that Black Sash, with its long experience advocating at international organisations, did not make broader use of international law, was surprising. As noted earlier, patterns of fixed preference are formed and operate inside international institutions, and create structural preferences (Koskenniemi, Citation2009:9). This includes international human rights treaty bodies as well as other inter-governmental bodies such as the World Bank and regulatory institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), which operates a dispute settlement body to address compliance with a wide range of international trade agreements and can serve as a partial restraint to liberalising social insurance measures (Busch & Reinhardt, Citation2000:167). In other words, both the World Bank and the WTO were key international agencies to focus on in advocating for social assistance.

Indeed, one exception to the lack of international law advocacy was in November 2017, when the Black Sash and Corruption Watch filed a separate complaint with the Ombudsman of the International Financial Corporation (IFC), which forms part of the World Bank group. This regarded an investment of USD 107 million made by the IFC in CPS and its American-owned holding company, Net1. The NGOs contended that IFC’s investment was in breach of the IFC’s own policy on environmental and sustainable development and requested a compliance appraisal and investigation (Black Sash et. al., Citation2017; Black Sash, Citation2017b).

However, broader reference could have been made to other international human rights regimes and Social Protection Floors (ILO, Citation2012). For example, the lack of broader access to social security has had a particularly devastating impact on children and women (Goldblatt, Citation2014). Hence, from the standpoint of equality, the concluding observations of human rights Treaty Body mechanisms, including, but not limited to the Committee on the Rights of Children (CRC) and Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) could have strengthened the NGOs claim and leveraged additional, external pressures, for example in a subsequent review process provided for in accordance with an international treaty.

Furthermore, claims could have been enriched by reference to the Sustainable Development Goals that were formulated in 2015 and administered by various United Nations agencies. Specifically, reference could have been made to the ‘multi-stakeholder Social Protection Systems and Floors Partnerships for SDG 1.3’, which through international alliances enables aims to ‘implement nationally appropriate social protection systems’. These are based on recommendations by the International Labour Organization and furthermore ‘grounded in international human rights instruments’ (United Nations, Citation2018).

In short, appealing to either the ILO, to the WTO and to human rights treaty bodies could have broadened the scope of the claim. This would have allowed Black Sash to leverage South Africa’s numerous, negotiated fixed preferences embedded in these international organisations to address deeper, globalised, structural inequalities that were responsible for increasing poverty in the country and had made social assistance such a crucial safety net for a growing number of South Africans.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we applied a legal mobilisation lens to a specific study of strategic litigation by NGOs to secure access to social assistance, arguing the relevance of legitimacy and capacity as well as the important roles that NGOs can play as translators of the global right to social security in locally-relevant contexts. We have also highlighted the potentially significant added-value of leveraging the structural bias of international institutions to strengthen national claims, and in particular how external pressures could be mobilised from various human rights treaty bodies, the International Labour Organization and other United Nations agencies.

From a legitimacy standpoint, highlighting state maladministration during tender procurement processes through the courts has been an important factor in not only exercising some level of judicial oversight over the state, but also raising public awareness of the financial and human costs of corruption committed by public officials at the highest level, and raising questions about the DSD’s legitimacy, and the government as a whole, in promoting socio-economic rights and addressing economic inequality. Moreover, the cases brought by NGOs on administration of the social grant system have gone beyond the departmental level. Further, the campaigns underpinning legal mobilisation on access to social assistance have strengthened public support for the removal of President Zuma and led to the redeployment of members of the executive in portfolios tasked with protecting the most marginalised.

Because of the significant media attention that high-profile litigation receives, the courts have become an important site of democratic contestation, where citizens are able to express their dissatisfaction with the executive and significantly influence political outcomes without relying on election cycles alone. The lower courts in particular have demonstrated their independence in holding the executive accountable and have become a means through which citizens sustain their commitment to a liberal democratic governance project.

Through exposing the wilful nature of maladministration by the executive, socio-economic rights litigation has advanced a core, liberal democratic goal of promoting equality before the law. Legal mobilisation strategies have moreover highlighted a corrupt relationship between members of the executive, and between the state and the private sector. However, individual responsibility is lacking; while Bathabile Dlamini was ordered by the Constitutional Court to provide testimony as to why she should not be held personally liable for maladministration and poor planning, she remained for some time afterwards a Minister in the government of Ramaphosa.

There remain at least three, specific and inter-related observations, deserving of further research, of how court-based, strategic litigation of social security claims on its own has inherent limitations in delivering socio-economic justice and denting the massive political, economic and social inequalities in South Africa. First, the procedural character of socio-economic rights claims through the courts has limited the courts’ ability to progressively realise these rights, containing the broader debate on social security to the realisation of access to social grants. Moreover, by failing to make more elaborate reference to international legal avenues, litigation strategies have been unable to transcend conventional legal argumentation. Second, while socio-economic rights litigation claims have highlighted administrative failures and wasteful expenditure of the post-apartheid liberal democratic administration, the extent to which the courts are willing to hold the executive accountable is heavily circumscribed. Finally, it remains troublesome to ensure the State’s compliance with court orders, which should at the very least be subject to further monitoring. Post-litigation monitoring has, indeed, been a persistent challenge in South Africa (Cote & van Garderen, Citation2011:181; Brickhill, Citation2018). This is especially complicated in the current instance since transition of grants administration from CPS to SASSA and SAPO was concluded in 2018 and thus falls outside the frame of the litigation.

Ultimately, the power of law-based advocacy is neither confined to litigation alone, nor is the Constitution only about claiming rights through the courts. Indeed, the interference of the courts in matters that fall outside of their expertise can risk creating perceptions of incompetence and illegitimacy (Dixon & Suk, Citation2018). In all matters of social and economic justice, including broader access to social assistance, legal mobilisation is about placing dignity and equality at the centre of all policy-making. Further, reducing inequality requires deeper structural reform of the political economy and an enhanced expertise on the part of policy-makers. Hence, inequality of access to social assistance can still be addressed by way of legal mobilisation, albeit as part of a comprehensive strategy combining litigation with public awareness and targeted campaigning of the legislature and the executive.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for feedback received by Dr. Meryl du Plessis of the University of the Witwatersrand. The authors also express appreciation to the anonymous referees for their feedback on earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abel, R, 1995. Politics by other means: Law in the struggle against apartheid, 1980–1994. Routledge, New York.

- AllPay, 2013. AllPay Consolidated Investment Holdings (Pty) Ltd & Others v Chief Executive Officer of the South African Social Security Agency & Others [2013] CCT 48/13 (Nos. 1 and 2).

- Ballard, R, Habib, A, Valodia, I & Zuern, E, 2005. Globalization, marginalization and contemporary social movements in South Africa. African Affairs 104, 615–634. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adi069

- van der Berg, S, 1997. South African social security under apartheid and beyond. Development Southern Africa 14, 481–503. doi: 10.1080/03768359708439982

- Bilchitz, D, 2003. Towards a reasonable approach to the minimum core: Laying the foundations for future socio-economic rights jurisprudence. South African Journal on Human Rights 19(1), 1–26. doi: 10.1080/19962126.2003.11865170

- Black Sash, 2017a. Heads of argument for the appellants’ applicant for leave to appeal, Supreme Court of Appeal, Case no. 752/2017, at para. 39.

- Black Sash, 2017b. Media statement: South African NGOs question IFC’s investment into Net1. https://www.blacksash.org.za/index.php/media-and-publications/media-statements/81-south-african-ngos-question-ifc-s-investment-into-net1.

- Black Sash, 2018a. Hands off our grants -what have we done to assist? https://www.blacksash.org.za/index.php/media-and-publications/media-statements/10-campaigns/hands-off-our-grants/390-hands-off-our-grants-what-have-we-done-to-assist.

- Black Sash, 2018b. Timeline of Events in #HandsOffOurGrant Campaign. https://www.blacksash.org.za/index.php/timeline-of-events.

- Black Sash, 2018c. Trust & Another v Minister of Social Development & Others CCT 48/17 (order dated 23 March 2018).

- Black Sash, Corruption Watch, Equal Education, 2017. Complaint: IFC $107 million investment in Net1 UEPS technologies Inc. https://www.blacksash.org.za/index.php/media-and-publications/media-statements/81-south-african-ngos-question-ifc-s-investment-into-net1.

- Brickhill, J (Eds.), 2018. Public interest litigation in South Africa. Juta, Johannesburg.

- Bruni, L, 2016. Reforming the social assistance system. In Alam, A et al. (Ed.), Making it happen – selected case studies of institutional reform in South Africa. World Bank Group, Washington, 119–133.

- Busch, M & Reinhardt, E, 2000. Bargaining in the shadow of the law: Early settlement in GATT/WTO disputes. Fordham Inernational Law Journal 24, 158–172.

- Chabalala, J, 2018. There will be chaos if the CPS contract is not extended, court hears. News24, https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/sassa-there-will-be-chaos-if-cps-contract-is-not-extended-court-hears-20180306.

- City Press, 2011. Social grants can’t be sustained: Zuma. News24, 24 November 2011. https://www.news24.com/Archives/City-Press/Social-grants-cant-be-sustained-Zuma-20150430.

- Corruption Watch, 2013. CW in successful R10 billion tender appeal. 2 December 2013, http://www.corruptionwatch.org.za/cw-in-successful-r10-billion-tender-appeal/.

- Cote, D & van Garderen, J, 2011. Challenges to public interest litigation in South Africa: External and Internal challenges to determining the public interest. South African Journal on Human Rights 27(1), 167–182. doi: 10.1080/19962126.2011.11865010

- Davis, R, 2018. Cabinet reshuffle: Bathabile Dlamini’s appointment disrespects ALL South African women. Daily Maverick, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-02-27-cabinet-reshuffle-bathabile-dlaminis-appointment-disrespects-all-south-african-women/#.WzFsCxJKiCQ.

- De Feyter, K, Parmentier, S & Timmerman, C, 2011. The local relevance of human rights. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Dixon, R & Suk, J, 2018. Liberal constitutionalism and economic inequality. The University of Chicago Law Review 85, 369–401.

- Donnelly, J, 2003. Universal human rights in theory and practice. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

- Du Toit, A, 2017. The real risks behind SA’s social grant payment crisis. Corruption Watch, 21 February 2017, http://www.corruptionwatch.org.za/real-risks-behind-sas-social-grant-payment-crisis/.

- Ehrlich, E, 1936. Fundamental Principles of the Sociology of Law. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Ewick, P & Silbey, S, 1998. The common place of law. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Ferreira, L, 2017. Factsheet: Social grants in South Africa- separating myth from reality. Africa Check, 28 February 2017. https://africacheck.org/factsheets/separating-myth-from-reality-a-guide-to-social-grants-in-south-africa/.

- Galanter, M, 1974. Why the "haves" Come out Ahead: Speculations on the limits of legal change. Law and Society Review 9, 95–160. doi: 10.2307/3053023

- Goldblatt, B, 2014. Social security in South Africa – A gender and human rights analysis. Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America 47(1), 22–42.

- Goodale, M & Merry, S, 2007. The practice of human rights: tracking law between the global and the local. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Gready, P, 2004. Fighting for human rights. Routledge, New York.

- GroundUp, 2017. GroundUp: Black Sash raises red flag over future of Sassa accounts. Daily Maverick, 17 October 2017, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-10-17-groundup-black-sash-raises-red-flag-over-future-of-sassa-accounts/#.WjgC1oVOJPY.

- Handmaker, J, 2019. Researching legal mobilisation and lawfare. ISS Working Paper Series, 641, The Hague, International Institute of Social Studies. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1765/115129.

- Handmaker, J & Arts, K, 2018. Mobilising international law as an instrument of global justice. In Handmaker and Arts (Eds.), Mobilising international Law for ‘global justice’. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1–21.

- Hertogh, M, 2004. A 'European' conception of legal consciousness: Rediscovering Eugen Ehrlich. Journal of Law and Society 31(4), 457–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6478.2004.00299.x

- Higgins, R, 1994. Problems and process: International law and how we use it. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Hoexter, C, 2006. Standards of review of administrative action: Review for reasonableness. In Klaaren, J (Ed.), A delicate balance: the place of the judiciary in a constitutional democracy. SiberInk, Cape Town, 61–72.

- Ignatieff, M, 1999. Whose universal values? The crisis in human rights. Stichting Praemium Erasmianum, Amsterdam.

- Ignatieff, M & Gutmann, A, 2001. Human rights as politics and idolatry. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- ILO, 2012. ILO social protection minimum floors. Recommendation 202 of 2012. Geneva, International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/secsoc/areas-of-work/legal-advice/WCMS_205341/lang–en/index.htm

- Klaaren, J (Ed.), 2006. In A delicate balance: The place of the judiciary in a constitutional democracy. SiberInk, Cape Town.

- Korey, W, 1998. NGOs and the Universal declaration of human rights: ‘a curious grapevine’. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

- Koskenniemi, M, 2009. The politics of international law – 20 years later. European Journal of International Law 20, 7–19. doi: 10.1093/ejil/chp006

- Koskenniemi, M, 2011. The politics of international law. Hart, Oxford.

- Langford, M, Cousins, B, Dugard, J & Madlingozi, T (Eds.), 2014. Socio-economic rights in South Africa: Symbols or substance? Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Marrian, N, 2017. SACP urges ANC to fire Bathabile. Business Day, 15 March 2017, https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/2017-03-15-sacp-urges-anc-to-fire-bathabile-dlamini/.

- Mazibuko, 2009. Mazibuko and Others v City of Johannesburg and Others (CCT 39/09).

- Merry, S, 1990. Getting justice and getting even: Legal consciousness among working-class Americans. Chicago University Press, Chicago.

- Merry, S, 2006. Transnational human rights and local activism: mapping the middle. American Anthropologist 108, 38–51. doi: 10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.38

- Modiri, J, 2018. Introduction to special issue: Conquest, constitutionalism and democratic contestations. South African Journal on Human Rights 34, 295–299. doi: 10.1080/02587203.2018.1552415

- Mutua, M, 2001. Human rights international NGOs: A critical Evaluation. In Welch, C. (Ed.), NGOs and human rights: Promise and Performance, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 151–159.

- Mutua, M, 2013. Human rights: A political and cultural critique. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

- Nattrass, N & Seekings, J, 2010. State, business and growth in post-apartheid South Africa. IPPG (Research programme consortium on improving Institutions for Pro-Poor Growth) Discussion Paper Series 34. www.ippg.org.uk/papers/dp34a.pdf.

- Nielsen, L, 2004. Situating legal consciousness: Experiences and attitudes of ordinary citizens about law and street harassment. Law and Society Review 34(4), 1055–1090. doi: 10.2307/3115131

- Pityana, S, 2017. Op-ed: Can South Africa’s constitutional democracy be sustained. Daily Maverick, 20 October 2017, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-10-20-op-ed-can-south-africas-constitutional-democracy-be-sustained/#.WjgC7oVOJPY.

- Rajagopal, R, 2003. International law from below: Development, social movements and third world resistance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Risse, T, Ropp, S & Sikkink, K, 1999. The power of human rights: international norms and domestic change. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Scott, C. (2004) Regulation in the Age of governance: The Rise of the post-regulatory state. In Jordana, J & Levi-Faur, D (Eds.), The politics of Regulation, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 145–174.

- Taekema, S, 2006. Beyond common sense: Philosophical pragmatism’s relevance to law. Retfæerd: Nordisk Juridisk Tidsskrift 29, 22–36.

- United Nations, 2008. General Comment 19: The right to social security UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, at its 39th session, UN Doc E/C 12/GC/19.

- United Nations, 2018. Social protection systems and floors partnerships for SDG 1.3, available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=16346.

- VvG, 2018. Anti-corruption expert interviewed by the authors on 22 August 2018.

- Wesson, M, 2004. Grootboomand Reassessing: Beyond the socioeconomic Jurisprudence of the South African Constitutional Court. South African Journal on Human Rights 20(2), 284–308. doi: 10.1080/19962126.2004.11864820

- Young, K, 2008. The minimum core of economic and social rights: A concept in search of content. Yale International Law Journal 13, 113–176.