ABSTRACT

Illustrating inequality to a more general public – beyond those concerned purely with public policy and research – presents various challenges. Museums have often served a function of memorialising both the impressive steps forward and major barriers to social progress, as a form of remembrance and understanding, although the twentieth century format in South Africa was generally embedded within colonial and racist self-glorification. The potential to transcend outmoded exhibition and museum politics with a new approach based on dialogical not didactic presentation, arises with inequality. In this exploration of how such an approach might unfold in the world's most unequal major city (as judged by the Palma Ratio), Johannesburg, the concept of threshold is introduced. Physical and conceptual access through overcoming thresholds is explored through a specific site, the Old Post Office, and through two artifacts that reveal structural power that generates inequality: Durban's sanitation system and Eastern Zimbabwe's diamond fields.

1. Introduction

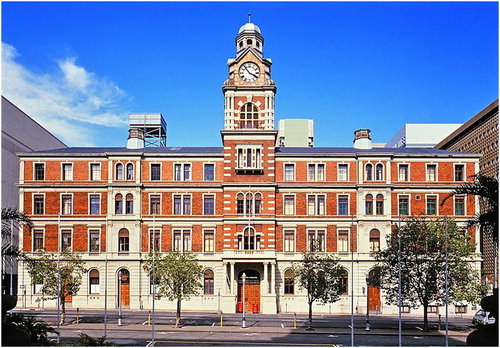

If you were to establish a museum of inequality, select an appropriate location and building and curate a couple of sample objects to represent inequality, where would you start? This question led us to Johannesburg's historic Rissik Street Post Office building, Durban's township toilets, and Zimbabwe's diamond fields. This article brings together ideas on how a museum and its objects can be used to address social inequalities, with the Rissik Street Post Office (RSPO) as a possible museum, and two exhibition case studies. We will look at how co-curatorship can be used as strategy in exhibition making by collaborating, sharing authority and working in dialogue with communities (Mallon, Citation2019; Schorch et al., Citation2019).

Applying this curatorial strategy with case studies from peri-urban Durban and rural villages in eastern Zimbabwe, we argue that an engagement with the community and their material culture validates community relationships to objects. Co-curation as a methodology also prioritises social histories and the collecting of contemporary cultures in a dialogue with the community. Unlike in the old colonial museum where objects were frozen in a timeless past in dioramas, co-curation transcends this practice and enables objects to be connected to the past and present in continuous ongoing relationships (McCarthy et al., Citation2019).

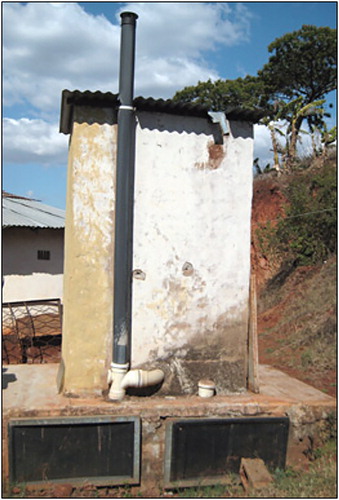

The first case study considers a toilet as a single-object study, an example of an artifact of inequality and of social differences – which, if represented in a museum exhibition, can form the focus of an engagement with complex issues relating to urban living. Space, race, class and gender are intertwined planes across which local-level inequality is reproduced: the example of Durban's celebrated sanitation innovations demonstrates what municipal officials term ‘differentiated’ designs of toilets based upon whether or not there are supplies of water for flushing, allowing a study to combine profits, policy and people in revealing ways.

The second case, an exhibition at Mutare Museum that opened in 2013, traced the discovery of alluvial diamonds in the Chiadzwa area in the Marange district of Zimbabwe. The exhibition documented the in-migration of thousands of illegal panners, followed by a military-Chinese joint venture. The diamonds caused the impoverishment of the local community, dispossession of land, and rapidly-rising social inequalities: the classic problem known as the resource curse.

By formulating exhibitions that address socio-cultural challenges facing communities such as these, museums can become active agents of social change. Once bastions of high culture which only kept objects for the public gaze, instead, museums can become interactive platforms where social issues can be articulated, discussed and solved for the benefit of once-marginalised people. Within this new vision undergirded by social activism and socially engaged activities that have a direct bearing on communities’ aspirations, the cases below illustrate how museums can be multi-vocal spaces, by curating stories as well as objects.

In this article we propose a praxis rooted in social struggles, a ‘social practice’ that addresses inequality through dialogical museological discourses that question structured systems of inequality. This dialogic praxis views the museum as an affective multilingual space that allows for diverse conversations by the previously marginalised (Golding & Modest, Citation2019). First, however, a literature survey reveals how museums are facing challenges of access and inclusion. We explore the concept of curatopia: an imagined ideal of socially and politically engaged curatorial practice for the future (Schorch et al., Citation2019). Then we ask whether this is possible in Johannesburg, a ‘broken’ city, with its frayed infrastructure, under-resourced museums and extreme, world-leading inequality. That sets the stage for discussing the representation of two case studies: Durban's sanitation system and Zimbabwe's diamond wealth.

2. Co-curation, collaborations and decolonial practices

The formation of many museums throughout Southern Africa is closely linked with the phenomenon of colonialism (Arinze, Citation1998). These museums were formed as a result of colonial encounters. They share a common history in terms of their development in that they tend to be the by-products of colonialism and are twentieth century creations – a period in which their formation came about as a result of European imperialism. Bvocho (Citation2013) argues that in most cases they were created in specific socio-political contexts that sought to denigrate the local populace, diminish self-confidence and to reduce pride in their past achievements.

For example, museums in Zimbabwe were built in the late 19th to mid-twentieth century, alongside the expansion of colonial rule. Museum construction was an integral part of the expansion of European capital and the establishment of political control, aspects that were always associated with racial prejudice as well as social and epistemic violence. The act of appropriating objects, recording their provenance and placing them in a museum while ignoring their social biographies constitutes epistemic violence (Vawda, Citation2019).

Museum making in early Rhodesia was at the impetus of the British South African Company (BSAC), a company formed with Queen Victoria's permission to acquire the natural and mineral resources as well as land in Southern Africa. The BSAC's expansionist agenda included sponsorship of scholars and scientists whose interests were to study, collect and appropriate the natural facets of the new colony. The work of corporations, interest groups and pseudo-scientists such as the Rhodesian Scientific Association (RSA), dominated the first museums in early Rhodesia. Museum collections were populated with artifacts gathered mostly by missionaries, colonial officials, the police, enthusiasts, scientists and intellectuals whose efforts filled in the museum vaults most times with poorly-documented material from African communities. Likewise in South Africa, prior to 1994 black communities were typically (though not always) represented in museums as objects of anthropological research (Dubin, Citation2006).

For many African museums burdened with collections uprooted from communities during the colonial era, a ‘decolonial’, museology that engenders a level of self-representation is a necessity, where previously marginalised knowledge can challenge colonially derived curatorial practices and reconnect objects with communities from which they were accumulated (Mignolo, Citation2011). Thus, co-curation can be used as curatorial strategy in sharing power with communities in the making of museum exhibitions. Co-curation is also a good strategy that is being actively embraced in decolonising museum practices. In light of this strategy, to decolonise the museum simply means a proper representation of people spoken about rather than listened to. Community engagement which informs co-curation is another decolonial museological strategy that can be used in researching and designing new exhibitions.

For many years museums in Southern Africa have been perceived as by-products of colonialism, whose main thrust has been to showcase the superiority of European cultures and the justification of ‘civilisation’ through imperialism, evangelism, and cultural negation and bombardment. This characterisation is still being used long after the end of both colonisation and apartheid. Consequently, museum practice has been exclusively detached from the people whose culture is presented in exhibitions. For this reason, according to Sandahl (Citation2019:75), ‘decolonising museum curating involves decoding museum collections from the colonial meanings in which they have been cut off, displayed and decontextualised from where they had once belonged.’ Sandahl (Citation2019:75) is especially concerned to question ‘the alien binary hierarchies of Western rationalism and the value systems of colonialism and imperialism.’

A decolonial strategy should be collaborative so that when an idea for an exhibition is first conceived, it should be a conversation with the local community, in part to assure permission to tell the community's story (Catlin-Legutko, Citation2019:41). Such collaborations need to occur at the beginning and threaded throughout the life of the exhibition. Meanwhile, Message (Citation2018) proposes a ‘disobedient museum’, which prioritises engagement through community participation outside the instrumentalised forms of knowledge production within archaeology, anthropology and ethnography. The disobedient museum embraces co-curatorship as a strategy to design exhibitions with the community in a non-disciplinary or undisciplined way (Message, Citation2018).

On the other hand, although museum practice was shaped by colonialism, by engaging in social activities and speaking for the rights of communities in exhibitions, the museum can become a relevant social-inclusion platform. Sandell (Citation2002:96) argues, ‘museums can impact positively on the lives of disadvantaged or marginalised individuals, act as a catalyst for social regeneration and as a vehicle for empowerment with specific communities and also contribute towards the creation of more equitable societies.’ Collaborations can potentially transform museums from being places that were once regarded as displaying ‘others’ to locations of cultural revitalisation, community voice and empowerment (Onciul, Citation2019:160). Consequently, accepting source communities as experts and research partners can change museum practice by opening up different ways of knowing and caring for the past (Onciul, Citation2019).

However, questions must be asked about the nature of communities, and the various ways in which museums can engage with them. Museum practices are influenced by various political and power imperatives, and museums themselves have always been purveyors of lopsided power relationships in community engagement, where the power of the museum – both as an institution and in its authorised curatorial practices – marginalise local communities (Hooper-Greenhill, Citation1992; Bennett, Citation1995). For this reason, rather than seeing a museum as a static monolithic institution at the centre of power, it can become a multi-vocal institution attempting to come to grips with effects of colonial encounter (Witcomb, Citation2007:142). Subsequently, through socio-political exhibitions, museums are becoming relevant insofar as communities can increasingly utilise them to exhibit their own history, identity and belonging (Watson, Citation2007).

In light of this, working with communities in the making of exhibitions presents opportunities for a shared engagement with plural voices incorporated into the narrative. Therefore, gradually the old practice that once defined museums in their predominant control of mediation, contextualisation and interpretation of objects, with curators regarded as authorised ‘keepers’, has been coming under scrutiny. This is because the museum is now redefined as an open public space that addresses contentious issues within community settings. The danger remains, however, that museums can also exercise a regulatory function that brings community members under a state's controlling gaze or into unwarranted civic obedience (Mignolo, Citation2011; Bennett, Citation2018; Dahre, Citation2019; De Palma, Citation2019).

In spite of this critique, exhibition design should place emphasis on collaborations and co-curatorship so as to replace former anonymous, institutional monolingual power with multiple voices from communities who adhere to different versions of the past (Haplin, Citation2007). The new planning, presentation and interpretive methods used in such exhibitions enable communities to become actively involved in self-representation or in critiques of cultural, economic or ideological impositions that affect them. Yekovich (Citation2016:243) argues that, with some guidance and training, community members should be allowed to curate their own exhibitions by determining what would be on display and how it would be presented.

This argument resonates well with our own methodological approach in which we regard co-curatorship as a strategy which can be embraced in making exhibitions. The proposed strategies below are informed by the notion of curatopia, which explores the ways in which mutual, asymmetrical power relations and scientific entanglements of the past can be transformed into more reciprocal, symmetrical forms of cross-cultural curatorship in the present (Schorch et al., Citation2019:2). Hence as a concept, curatopia looks at an emerging active reciprocal relationship between communities and museums. In the same vein, Simpsons (Citation2001:247) acknowledges that whilst in the past museums were perceived as elitist institutions, today they are developing closer working relationships with communities whose cultures and concerns they interpret. These views can also be read in light of what Meskell (Citation2009) describes as a cosmopolitan approach in which experts are collaborating and sharing knowledge of the past with communities.

In this process, museum curators become facilitators and not undisputable champions with authorised knowledge. Curatorship has thus evolved from being a strict, specialised connoisseurship of individuals to a public service that attend to problems in contemporary communities (Schorch et al., Citation2019). Hence, communities are valuable sources of expertise and partners in knowledge creation and not passive recipients of authorised discourses. They no longer just enjoy museum products, but also actively direct the activities of museums (Pham, Citation2019).

This collaborative approach to exhibition production is reflective of shared authority between the community and museum curators. Exhibitions have become more than just sites for the manifestation of preconceived curatorial theory but are increasingly sites of collaborative research and knowledge production (Butler & Lehrer, Citation2016). They have shifted from the status of merely presenting concluded results, into important active venues for analysing social issues and producing relevant knowledge (Iervolino & Sandell, Citation2016; Bjerregaard, Citation2019; Dahre, Citation2019; Hansen et al., Citation2019).

This is far preferable to the role of traditional curators who operate as discrete and invisible exhibition makers (Arero & Kingdon, Citation2005; Hansen et al., Citation2019). Thus, the collaborative approach gives room for more participatory and co-curated exhibition making practices. A collaborative methodology in a museum has been described by Shelton (Citation2018) as encompassing three elements:

transforming the role of a curator into a facilitator in which the community independently takes charge and determines the subject of an exhibition; collaboration in periodic dialogues with the community to ensure the fidelity of the exhibition with their expectations; and collaboration as a dialogic process through which culture is generated in conversations between curators and the community representatives (Shelton, Citation2018:xviii).

In contrast, a community museum is locally accented, self-announcing and self-conscious (Kingdon, Citation2005). In light of these differences, we argue that the recent emergence of community museums in Africa can be regarded as a decolonial methodology, one embraced by local people in response to exclusion or misrepresentations in national museums. This view is supported by Boast (Citation2011:14) who succinctly argues that ‘due to frustrations with engagements with existing national museums and a complete insignificance of national museums to the community – indigenous people are creating their own centres of collecting, performance and presentation.’

The emergence of community museums in Australia, North America, Africa and New Zealand enabled these institutions to act as sites of recovery that created a sense of community ownership and identity (Murray & Witz, Citation2014:8). Examples of community museums in Zimbabwe that were established after independence in 1980 are the BaTonga community museum in Binga, the Nambiya community museum in Hwange, the Old Bulawayo open air museum in Bulawayo and the Marange Community museum in Mutare.Footnote1

Murray & Witz (Citation2014) also illustrated the collaborative formation of a community museum in Lwandle in Western Cape, South Africa. The project was not a set of prescribed ideas and practices but a negotiated space of thinking in what became the first township based museum in the Western Cape (Murray & Witz, Citation2014:13). The museum was created from a migrant labour hostel which was restored and curated as a memorial space exploring the experiences and lives of the hostel dwellers during apartheid. Therefore, a visitor to this museum ‘ … could see how hostels had become homes, how a labour compound had become a township, how racial exclusion had given way to multiracial democracy’ (Peterson, Citation2015:31). Still in South Africa, the District Six museum was opened in 1994 as a community museum honouring the experience of 60,000 people who were forcibly removed from their homes by the apartheid government in Cape Town between 1970–80 (Peterson, Citation2015:17). In London, the Natural History Museum is striving to challenge the way people think about the natural world by stimulating public debate. This museum attempts to ‘collaborate with the public in deriving their own meaning from natural heritage they encounter in the museum and in nature’ (Mensch & Mensch, Citation2015:16).

According to Sandell (Citation2017:2), museums’ choices regarding narratives that are constructed and publicly presented can reinforce, challenge or potentially reconfigure prevailing normative ideas about right and wrong, good and bad, fairness and injustice. Sandell (Citation2017) explores the idea of a museum as site for activism where efforts are made by different groups of people in bringing about social and political change through dialogue. Through addressing burning issues and opening its doors to various communities by curating socially relevant exhibitions, museums in Southern Africa can reimagine themselves by reducing a dominant western perspective in which they originated and in becoming more sensitive to the multiple voices that should share in the mediation of relevance and meaning in the contemporary museum. Therefore, giving a voice to communities can become a vital aspect of knowledge production to accompany and influence the mediation and skills of curators, exhibition designers and educators.

Such curatorial reforms would also counter a growing critique that community participation and collaborations are terms often used in contemporary museum theory and practice to gloss over the complexity of community identities, which has led to claims of tokenistic inclusion by museums (Golding & Modest, Citation2013). A similar critique of the collaboration process is usually around the location of power in these activities (La Salle, Citation2010; Chipangura, Citation2019; Golding & Walklate, Citation2019). For this reason, Boast (Citation2011:48) argues that no matter how much we might think of pluralising knowledge production in museums through collaborations, the intellectual control will still remain vested in the hands of curators. The solution is, often, to ensure strong, grounded activist leaders from communities are integrally involved, including those committed to social practice in art, architecture and urban design – as is illustrated in central Johannesburg.

3. Could the Old Rissik Street Post Office become a Museum of Inequality?

What kind of learning would occur in a Museum of Inequality? In creating such a museum, what might its host site consist of, with which partners? To answer these questions, we began to seek out artists with an interest in representations of inequality, who have a developed social practice that goes beyond the (commodified) art object into social processes and intangible encounters.

We hosted two ‘Social Practice Studios’ at 56 Pim Street,Footnote2 in Newtown, to look at developing ways to model engagements between the University and the City. The decision to host these engagements away from the university, in town rather than on the campus, was taken because of some of the barriers that exist in accessing the campus. This instance of social practice focused on engaging with the cultural infrastructure of the City of Johannesburg, with the RSPO at the centre of our enquiry. Our interest lay in the possibility of reusing City heritage buildings, and making public infrastructure accessible to ordinary people.

Using Newtown as the base, we were able to talk to artists, performers, cultural activists, city planners, architects, urban designers, sociologists, museologists and local residents. The interaction included discussions and a small exhibition of current work by a number of academics, students and artists, as well as proposals for a future museum. We undertook some investigation into social practice including looking at working methods in the arts, both object-based and performance-based. Social practice has been informed by community-based urban design practitioners, protest and resistance artists, community-based cultural workers, and non-profit organisations, and can be traced back to the 1970s. We were introduced to case studies of museum and heritage developments, and what they tell us about methods of public engagement and its impact on the delivery of effective social services including access to museums.Footnote3

We tested and explored objects, ideas, photographs, films and forms of display. We came up with a ‘Peep Hole’ exhibit as a way of enabling the passing commuters to see evidence of what we created. We took part in an Open Day in the Newtown precinct, as part of a larger event where agents appointed by the Johannesburg Development Agency conducted interviews with local residents to provide input into the new 5-year development plan for Newtown. There were a range of creative companies doing work that could readily inform an inclusionary museological practice, including the hugely innovative Play Africa Programme engaging in early childhood development, based at Constitutional Hill.

We invited the group of artists, researchers and others to undertake a walking tour of the RSPO, from Gwigwi Mrwebi Street Newtown, into the Civic Spine, and then a visit to other historic spaces and repurposed buildings on its threshold. A group of about 30 of us walked the back streets and arrived at the back gate of the RSPO below an enormous South African flag, painted across the full south end of the building. With our hard hats on, and sturdy shoes, we ready to be introduced to this broken and damaged remnant of the iconic post office, by the head of Heritage for the City of Johannesburg, Eric Itzkin.

The Old Post Office building in the City of Johannesburg, built in 1895, ceased being a Post Office in the 1990s (). In 2009 the Johannesburg Property Company had responsibility for the security of the RSPO but to cut costs so as to fund 2010 World Cup activities, withdrew security. This led to an occupation by homeless people, and the building was gutted by fire on November 1, 2009. It was almost demolished, but heritage activists and the Provincial Heritage Resources Agency ensured that it would be restored. It is now receiving a R40 million facelift from the City (). Could this building offer some critical thoughts and possible answers to the desire for a museological response to inequality? The study of the RSPO takes place against a history of a city constantly building, breaking, rebuilding and restoring over 130 years. The RSPO is one of the very few buildings that remain from the first decade of the town.

Figure 1. Rissik Street Post Office, 1988. Source: Wikipedia commons, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:9_2_228_0067-Post_Office-Johannesburg-s.jpg.

The tour of the RSPO and its immediate eco-system including the walk from Newtown of no more than half a dozen city blocks, was an encounter with broken thresholds, empty buildings, damaged pavements and unsafe streets. How could a museum of inequality begin to operate, in this context? It became clear that we were not simply dealing with a building, but a dysfunctional neighbourhood. Broken thresholds would forever bedevil any attempt at a museum dealing with social inclusion.

In short, points of entry to Johannesburg's public museums are often closed, with human access denied or restricted in favour of vehicular access. The security design solutions at these thresholds are now increasingly systems of electronic surveillance and technologies of restriction and control. This prevents equality of access. Can innovative design change this interface?

‘Social practice’ implies an ability to work effectively across what appear to be impermeable boundaries and thresholds. Could we begin to describe a ‘Johannesburg social practice’ and a new ‘Museum social practice’ that would enable us to believe that the RSPO could become a Museum of Inequality? Returning to the question of location and site, if the RSPO was to become a Museum of Inequality, one would have to do more than redesign the building. One would have to engage with the surrounding environment. The idea that the museum alone could transform the neighbourhood and become meaningful and of use to an excluded and marginalised community, would require a much broader vision.

4. The toilet as an object of inequality: the threshold of water-borne sanitation

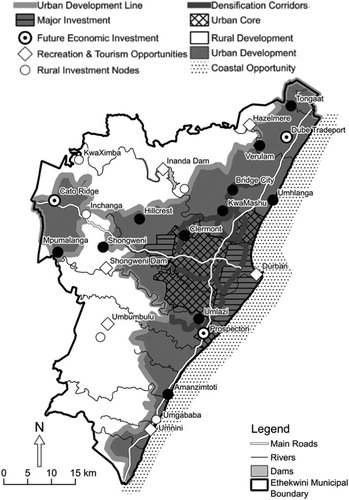

What is the case for including differentiated sanitation within the scope of inequality representation, as a potential exhibition? A million or more Durban residents – nearly a third of the city's residents – lack adequate sanitation within their dwellings or yards. Perhaps most notoriously, water and sewage pipes that crisscross the northern part of Durban are fed mainly from the Inanda Dam, which displaced thousands when constructed during the dying years of apartheid. Their land compensation was only won after lengthy struggles in 2015. Yet for tens of thousands of households in the dam's close vicinity – the Valley of a Thousand Hills – there is no water provided for low-income families to flush (only 200 litres per household per day allow consumption through on-site tanks not connected to cisterns).

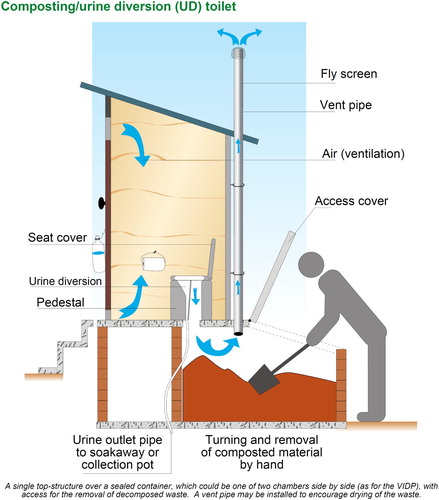

This instance of structured inequality through artificial water scarcity was the result of an oft-celebrated public policy. According to a 2012 Guardian report, ‘Ground zero for the quest to find the perfect toilet for the twenty-first century's needs may as well be Durban, South Africa’ (Kaye, Citation2012). With the enthusiastic support of the world's then richest man, Bill Gates (), who is earnestly searching for ways to ‘reinvent the toilet’ for poor people, the area was switched from Ventilated Improved Pit-latrines to Urine Diversion (UD) toilets. The latter make provision for urine to collect in one ‘soak-away’ bucket and solids in another, where after sawdust or sand is added, the faeces will dry and gradually kill off pathogens. On behalf of the municipality, Teddy Gounden, Bill Pfaff, Macleod and Chris Buckley (Citation2013) explained, ‘The householder is required to remove the contents, dig a hole and bury the contents on site.’

Figure 3. Neil Macleod and Bill Gates consider Durban sanitation. Source: https://www.gatesnotes.com/Development/Simple-Affordable-Sanitation-Innovation-in-Durban.

As a ‘neoliberal loo’, the UD was attractive to the city because it would not require new piping nor pumping costly water into the lower-income neighbourhoods. And instead of the city vacuuming out the excrement (as was meant to be the case for the VIPs), households themselves would empty the faeces chamber. Beginning in 2003, more than 80,000 UDs were placed in Durban's semi-peripheral areas, even though they were very poorly received from the outset. To the extent that UDs were used at all, they functioned mainly not as they were designed, but instead, as either storehouses or as a top structure for newly-dug septic tanks. (The latter were supplied water through new, informal piping that carries less than a dozen-litre flush a short distance to disposal.)

Geographic discrimination associated with UDs is striking. City water chief executive Neil Macleod (Citation2008a:2) mapped a ‘sanitation edge’ outside of which a vast peripheral band of the municipality was considered too poor to justify laying sewage pipes and treatment facilities (). Rationalised Macleod (Citation2008b), ‘A piped sewerage system is not economically justifiable in rural areas, where the densities are too low, and in these areas onsite sanitation is the only viable option available.’

Figure 4. Ethekwini urban development line (water-borne sanitation threshold). Source: Ethekwini Municipal Authority (Citation2014:128).

Flaws in the ‘economically justifiable’ denial of flush toilet systems were soon obvious. One is the blurred distinction between solids and liquids, given that diarrhoea often accompanies AIDS-related opportunistic diseases, and Durban has the world's highest level of urban HIV+ prevalence. Durban's extreme summer humidity for several months a year makes drying anything difficult. Most Durban townships and especially shack settlements suffer hilly terrain. Homes are often located on steep slopes, suffering poor drainage and facing often turbulent rain, leaving any structure – especially a small UD – vulnerable to landslides.

Nevertheless, the merits of UDs were overwhelming to the city, according to Macleod (Citation2008a:8): they used ‘minimum amounts of water, if at all.’ Indeed, the UD is designed to not use any flushing mechanism ( and ). The capital cost of each UD toilet was an average of $500, but municipal maintenance costs fell away because ‘emptying is the responsibility of the household, with entrepreneurs already offering their services at $4 per chamber emptied’ (Macleod, Citation2008a: 8–9). Macleod (Citation2008a:8–11) claimed, ‘follow up visits after construction have increased acceptance levels and emphasised the family's responsibilities for maintenance of the toilet. The period needed for follow ups extends to years’ because of the need to ‘evaluate acceptance of the solution and to confirm that the hygiene messages have been internalised.’ This innovation most impressed a Science journalist (Koenig, Citation2008:744), whose laudatory article termed UD the ‘best solution’ for sanitation in Durban.

Figure 6. The UD toilet’s design. Source: Macleod (Citation2008b).

Communities protested (Bond, Citation2019), and according to journalists at Durban's Daily News: ‘Local residents who complained are aghast, not only at the unbearable stench, but the thought of digging out their own waste and using it on their vegetable patches’ (Adriaan et al., Citation2010). By early 2014, a municipal/academic survey of 17,000 recipients of the UD toilet made it evident that the system had failed (Coertzen, Citation2014). Fully 99 percent of respondents who received UDs observed that instead, a flush toilet inside their house would be optimal; many used the flush toilet at work in the city but when back in peri-urban home areas were unhappy about substandard sanitation. Foul smells were the biggest complaint, causing 80 percent dissatisfaction. There were inadequate instructions on emptying the excrement, include digging a pit and planting a papaya tree.

By 2014 the overwhelmingly negative reaction was forcing another municipal rethink, leading to a new strategy of converting the UDs into low-flush systems with mini septic tanks. To Macleod’s (Citation2014) credit, upon receiving the Stockholm Water Industry Award in 2014, he openly conceded that the pipeless strategy entailed class discrimination (even if ‘perceived’):

[In the future] we’ll bring safe sanitation at an acceptable level to rich and poor alike and we’ll do away with this perceived discrimination where the flushing toilet is seen to be for rich people and dry sanitation is seen to be a solution for poor people. Our challenge is to do away with that differentiation.

All these features – profits, policy and people (especially community organisations) – must be properly understood by museum curators in such circumstances, to ensure dialogical opportunities arise. Hence a toilet exhibition, such as one offered at the inaugural Wits Centre for Inequality Studies conference as a case study in mid-2018, reflects a complicated weaving of experiential and structural-explanatory narratives. The kinds of debates that occur in Durban itself are vital to reflect, e.g. through protest paraphernalia, videos and other means of visual communication that transmit complicated constraints that affect state policy in one of the world's most unequal cities.

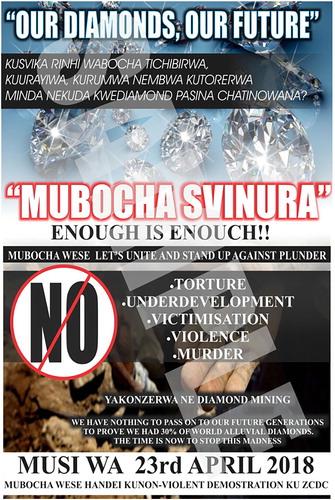

5. Inequalities among resource beneficiaries: Zimbabwe's diamonds

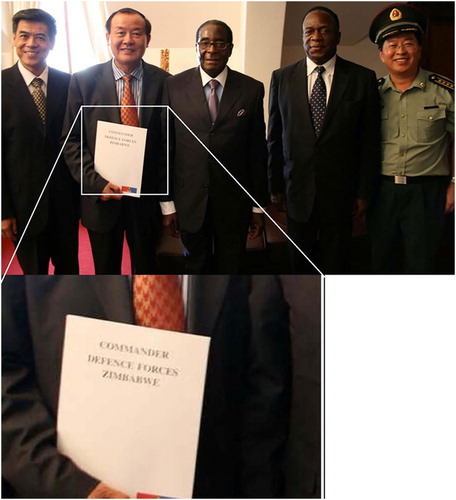

The discovery of surface diamonds in eastern Zimbabwe in 2006 triggered a massive invasion of the area by ‘illegal panners’, known in local parlance as makorokoza/magweja. The alluvial diamond fields are in the municipal ward of Chiadzwa, within Marange District, about 80 miles southwest of the city of Mutare in Manicaland Province. Until late 2008, ‘illegal diamond mining’ in the area continued unabated with the local community also joining the enterprise, until an army massacre of hundreds of artisanal mineworkers ended local redistributive opportunities. Instead of a resource boon, the diamond immediately became an object of inequality. Local villagers were displaced to pave the way for the establishment of formal Chinese-Zimbabwean diamond mining companies, led by the Anjin joint venture with the military (Maguwu, Citation2013) ().

Figure 7. Zimbabwean and Chinese allies planning Chiadzwa diamond mining. Source: Centre for Natural Resource Governance.

Robert Mugabe estimated in 2016 that of a potential $15 billion in alluvial diamond revenues from Chiadzwa, only $2 billion was realised, as a result of widespread thieving by elites (mainly the Zimbabwean military and Chinese mining officials). Villagers who were displaced by the advent of formal mining were relocated to Arda Transau, a government farm in Odzi located 75 km North West of their original homesteads ( and ).

Figure 9. Diamond mining using machinery imported by Anjin. Source: Centre for Natural Resource Governance.

In spite of state repression, Mutare Museum took up this contentious issue and tackled social inequalities by actively engaging disfranchised villagers through an exhibition that stimulated public dialogue and debate. The Mutare Museum is one of the five regional museums under national administration. All the country's museums were established as result of colonial encounters.

The exhibition explored the Chiadzwa story in its full length: from the discovery of the diamonds in the illegal phase, to the cordoning off of the area and the setting up of the so called ‘formal mines’ which resulted in the displacement of communities that had lived around the area for more than seventy-five years. The objective was to give the public an in-depth understanding of events that triggered the discovery and subsequent invasion of one of the biggest diamond mining fields in Sub Saharan Africa.

This exhibition – Diamonds: the Wealth Beneath Our Feet – allowed the museum to move away from its role as authoritative educator and become a facilitator of dialogue and debate as well an actor in defining and upholding human rights. Apart from school children who frequented the museum to see the exhibition because of its educational value (since it closely interrogated some of key themes in their history and geography syllabi), other visitors came from civic organisations, mining companies, local authorities, government departments as well as the villagers whose stories were being represented. By undertaking this kind of an exhibition, it can be argued that Mutare museum embraced what Karp & Kratz (Citation2015: 4) call the ‘interrogative museum’, which purposefully moves away from ‘exhibitions that seem to deliver a lecture [which] might be declarative, indicative, or even imperative in mood – to a more dialogue-based sense of asking a series of questions’.

By addressing contentious issues that surrounded the mining of diamonds and the loss of cultural and land rights by villagers who once lived close to the mining fields, the exhibition allowed the demand for compensation to gain increasing public attention.

Reflecting ongoing dissent about inequality in beneficiaries, on 23 April 2018, the few remaining villagers still living close to Chiadzwa staged a demonstration demanding an end to theft of diamonds, torture, victimisation, indiscriminate shootings and continuous displacement from their agricultural fields (). The protesters were met with heavy police repression, including tear gas and dogs.

6. Conclusion

In this article we attempted to show how a museum and its exhibits can confront social inequalities. We posed several questions. Could the proposed transformation of Rissik Street Post Office into a museum bring together communities that were once marginalised during the apartheid period, and what kinds of partnerships are required to overcome the broken threshold? What mode of exhibiting can assist in transcending twentieth-century museology? Can a dialogic experience explain structural factors creating inequality, in a way that does not become didactic?

To that latter end, we explored two sources of inequality that lend themselves to exhibition. First is the sanitation debate, and specifically how Durban's neoliberal loo strategy ensured innovation was provided on the cheap, but with many resulting problems. The basic problem is neither personalities nor bureaucratic agency, although both do feature in the story, given Gates’ interest and MacLeod's status. Instead, the underlying problem is structural: the denial of funding to poor people, even at a time massive municipal infrastructure investments were underway – for example, the Moses Mabhida soccer stadium, built next to a perfectly functional existing stadium, or a new airport, or port and road expansion – that mainly serve corporations and wealthy residents and visitors.

Diamond mining in Chiadzwa, Zimbabwe was also considered, with communities living in and around the fields suffering a resource curse. Chinese companies were given mining rights by the government and in the process villagers were displaced and relocated to another area without proper compensation. Mutare Museum's exhibition stimulated useful debate that saw some of the socio-cultural problems faced by villagers of Chiadzwa being addressed.

These topics are diverse, yet the resolution of the complicated representational problems can be envisaged within a future proposal for a Museum of Inequality. The museum scholarship we have considered points to dialogical not didactic approaches. The expansion of the field beyond experiential towards structural explanation, and then action, requires the appropriate setting (e.g. a refurbished RSPO). To these ends, an awareness of thresholds is one of the vital threads that allow an engagement with inequality to become more than an academic exercise or museum exhibition – but one that results in social dialogue around corrective action.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Patrick Bond http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6657-7898

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The BaTonga community museum was established in 2003 and has been successful in presenting and preserving Tonga cultural histories found mostly in north western Zimbabwe, especially in the wake of the devastating mid-1950s Kariba Dam displacements. This museum has a collection of cultural objects made by the Tonga community and reflects how these objects are used in everyday practices (Chikozho Citation2015). Similarly, the Nambiya museum collects and displays objects of a small ethnic group whose cultural practices are slowly fading away. The Old Bulawayo open air museum is a celebration of Ndebele cultures and traditional ways of life. Displays at Marange Museum portray various aspects of identity and seek to celebrate cultural richness, creativity and resourcefulness. The museum started off as a community initiative with a view to creating a repository of Marange heritage and culture. The main museum building has seven galleries: the Wonder Room, the Faith Room, the Entertainment Hall, The Hall of Outstanding Achievers, the Presidents’ Room, the Craft Gallery and the Genealogy Gateway Gallery. These displays place emphasis on creating a space for community activities, events, performances, intergenerational storytelling and educational programmes.

2 Albonico Sack Associates, Pim Studios have undertaken numerous Urban Design and Architectural developments on behalf of the Johannesburg Development Agency. We put out a call to interested researchers, professionals and members of the public, as well as collaborators pursuing similar work at the University of Richmond in the U.S. State of Virginia. There, the Bonner Center for Civic Engagement is beginning a process to address colonial legacies and contested spaces and histories, through a museum of inequality project.

3 Totem-Media is a company that has developed a number of key museums including the Origins Centre at Wits.

References

- Adriaan, T, Ngcobo, W & Mngoma, N, 2010. We have to live with that smell. Daily News, 25 August.

- Arero, H & Kingdon, Z (Eds.), 2005. East African contours. The Horniman Museum and Gardens, London.

- Arinze, E, 1998. African museums: The challenge of change. Museum International 50(1), 31–7. doi: 10.1111/1468-0033.00133

- Bennett, T, 1995. The birth of the museum. Routledge, New York.

- Bennett, T, 2018. Introduction. Museum Worlds 6, 1–16. doi: 10.3167/armw.2018.060102

- Bjerregaard, P, 2019. Exhibitions as research, curator as distraction. In Hansen, M, Henningsen, A & Gregersen, A (Eds.), Curatorial challenges, 108–20. Routledge, London.

- Boast, R, 2011. Neocolonial collaboration. Museum Anthropology 56(1), 65–70.

- Bond, P, 2019. Class, race, space and the ‘right to sanitation’. In Sultana, F & Loftus, A (Eds.), Water politics, 189–202. Routledge, London.

- Butler, S & Lehrer, E, 2016. Introduction. In Butler, S & Lehrer, E (Eds.), Curatorial dreams, 3–26. McGill-Queen’s University Press, London.

- Bvocho, G, 2013. Multimedia, museums and the public. Museum Memoir No. 3, Harare: National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe.

- Catlin-Legutko, C, 2019. History that promotes understanding in a diverse society. In Cole, J & Lott, L (Eds.), Diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion in museums, 41–8. Rowman and Littlefield, London.

- Chikozho, J, 2015. Community museums in Zimbabwe as a means of engagement and empowerment. In Mawere, M, Chiwaura, H & Thondhlana, T (Eds.), African museums in the making, 47–68. Langaa Research and Publishing Common Initiative Group, Bermuda.

- Chipangura, N, 2019. The archaeology of contemporary artisanal gold mining at Mutanda Site, Eastern Zimbabwe. Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage 6(3), 189–203. doi: 10.1080/20518196.2019.1611184

- Chipangura, N & Chipangura, P, 2019. Community museums and rethinking the colonial frame of national museums in Zimbabwe. Museum Management and Curatorship. doi: 10.1080/09647775.2019.1683882

- Coertzen, M, 2014. Urine Diversion in Durban. Interview, 14 January, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

- Dahre, UJ, 2019. On the way out? The current transformation of ethnographic museums. In Golding, V & Walklate, J (Eds.), Museums and communities: Diversity, dialogue and collaborations in an age of migrations, 61–87. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge.

- De Palma, MC, 2019. Selfies, yoga and hip hop: Expanding the roles of museums. In Golding, V & Walklate, J (Eds.), Museums and communities: Diversity, dialogue and collaborations in an age of migrations, 230–59. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge.

- Dubin, S, 2006. Transforming museums. Palgrave, New York.

- eThekwini Municipal Authority, 2014. Spatial development framework report, 2014–15. Durban.

- Golding, V & Modest, W, 2013. Museums and community. Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

- Golding, V & Modest, W, 2019. Thinking and working through differences: Remaking the ethnographic museum in the global contemporary. In Schorch, P, McCarthy, C & Durr, E (Eds.), Curatopia, museums and the future of curatorship, 90–106. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

- Golding, V & Walklate, J, 2019. Introduction: Crossing the frontier: Locating museums and communities in an age of migrations. In Golding, V & Walklate, J (Eds.), Museums and communities: Diversity, dialogue and collaborations in an age of migrations, 1–20. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge.

- Gounden, T, Pfaff, B, Macleod, N & Buckley, C, 2013. Tackling Durban's sanitation crisis head on. Infrastructure News, 9 January. http://www.infrastructurene.ws/2013/01/09/tackling-durbans-sanitation-crisis-head-on/ Accessed 12 December 2019.

- Hansen, MV, Henningsen, AF & Gregersen, A, 2019. Introduction. In Hansen, MV, Henningsen, AF & Gregersen, A (Eds.), Curatorial challenges, 1–16. Routledge, London.

- Haplin, MM, 2007. ‘Play it again, Sam’: Reflections on a new museology. In Watson, S (Ed.), Museums and their communities, 47–53. Routledge, London.

- Hooper-Greenhill, E, 1992. Museums and the shaping of knowledge. Routledge, London.

- Iervolino, S & Sandell, R, 2016. The world in one city: The Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam. In Butler, SR & Lehrer, E (Eds.), Curatorial dreams, 211–30. McGill-Queen’s University Press, London.

- Karp, I & Kratz, C, 2015. The interrogative museum. In Silverman, R (Ed.), Translating knowledge, 5–20. Routledge, New York.

- Kaye, L, 2012. What is the future of toilet technology? The Guardian, 9 October, http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/future-toilet-technology-sanitation-water.

- Kingdon, Z. 2005. Creative frontiers. In Arero, H & Kingdon, Z (Eds.), East African contours, 1–20. The Horniman Museum and Gardens, London.

- Koenig, R, 2008. Durban’s poor get water services long denied. Science 319, 744–5. doi: 10.1126/science.319.5864.744

- La Salle, M, 2010. Community collaboration and other good intentions. Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress 6(3), 401–22. doi: 10.1007/s11759-010-9150-8

- Macleod, N, 2008a. Reaching low income communities. Presentation to the AfriSan Conference, 18–20 February, Durban. https://www.slideserve.com/loren/africasan-reaching-low-income-communities-experiences-from-ethekwini-durban-powerpoint-ppt-presentation Accessed 12 December 2019.

- Macleod, N, 2008b. We are committed to cleaner rivers. The Mercury, 19 February.

- Macleod, N, 2014. Video interview, Stockholm. http://www.siwi.org/prizes/stockholmindustrywateraward/winners/2014-2/.

- Maguwu, F, 2013. Marange diamonds and Zimbabwe’s political transition. Journal of Peacebuilding and Development 8(1), 74–8. doi: 10.1080/15423166.2013.789271

- Mallon, S, 2019. He alo a he alo/kanohi kit e kanohi/ face to face: Curatorial bodies, encounters and relations. In Schorch, P, McCarthy, C & Durr, E (Eds.), Curatopia, museums and the future of curatorship, 88–98. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

- McCarthy, C, Hakiwai, A & Schorch, P, 2019. The figure of the kaitiaki. In Schorch, P, McCarthy, C & Durr, E (Eds.), Curatopia, museums and the future of curatorship, 211–22. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

- Mensch, P & Mensch, LM, 2015. New trends in museology II. Muzej novejse zgodovine, Celje.

- Meskell, L, 2009. Cosmopolitan archaeologies. Duke University Press, Duke.

- Message, K, 2018. The disobedient museum: Writing at the edge. Routledge, London.

- Mignolo, W, 2011. Museums in the colonial horizon of modernity. In Harris, J (Ed.), Globalisation and contemporary art, 71–85. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester.

- Murray, N & Witz, L, 2014. Hostels, homes, museum. University of Cape Town Press, Cape Town.

- Onciul, B, 2019. Community engagement, indigenous heritage and the complex figure of the curator. In Schorch, P, McCarthy, C & Durr, E (Eds.), Curatopia, museums and the future of curatorship, 159–75. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

- Peterson, D, 2015. Introduction. In Peterson, D, Gavua, K & Rassool, C (Eds.), The politics of heritage in Africa, 1–36. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Pham, C, 2019. How museums identify and faces challenges with diverse communities. In Golding, V & Walklate, J (Eds.), Museums and communities, 106–19. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge.

- Sandahl, J, 2019. Curating across the colonial divides. In Schorch, P, McCarthy, C & Durr, E (Eds.), Curatopia, museums and the future of curatorship, 72–89. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

- Sandell, R, (Ed.), 2002. Museums, society, inequality. Routledge, London.

- Sandell, R, 2017. Museums, moralities and human rights. Routledge, London.

- Schorch, P, McCarthy, C & Durr, E, (Eds.), 2019. In Curatopia, museums and the future of curatorship. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

- Shelton, A, 2018. Heterodoxy and the internationalisation and regionalisation of museums and museology. In Laely, T, Meyer, M & Schwere, R (Eds.), Museum cooperation between Africa and Europe, 15–6. Fountain Publishers, Kampala.

- Simpsons, MG, 2001. Making representations. Routledge, London and New York.

- Stanley, N, 2008. Introduction. In Stanley, N (Ed.), The future of indigenous Museums, 1–22. Berghahn Books, New York.

- Sweet, J & Kelly, M, 2019. Museum development and cultural representation. Routledge, London.

- Vawda, S, 2019. Museums and the epistemology of injustice: From colonialism to decoloniality. Museum International 71, 72–9. doi: 10.1080/13500775.2019.1638031

- Watson, S, (Ed.), 2007. In Museums and their communities. Routledge, London.

- Witcomb, A, 2007. A place for all of us? In Watson, S (Ed.), Museums and their communities, 133–56. Routledge, London.

- Yekovich, S, 2016. Ethics in a changing social landscape. In Murphy, B (Ed.), Museums, ethics and cultural heritage, 242–50. Routledge, London and New York.