ABSTRACT

Climate change is arguably one of the biggest challenges globally. In order for countries to meet the commitments of the Paris Agreement, climate investments need to be scaled up for adaptation and mitigation strategies. Green bonds are one of the most emerging climate finance mechanisms for large-scale climate projects and offer investment opportunities for many developing countries. Most developing countries are heavily reliant on climate funds which are insufficient. Hence, the urgent need to tap into emerging climate finances such as green bonds. Out of all the regions, Africa is expected to be the worst impacted by climate change and green bonds can contribute to the much needed climate finances. The growth of the green bond market has been observed in the economic hubs of the continent with countries such as Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa demonstrating huge potential in being active and contributing to the growth of the market. However, this paper recommends that for the green bond market to further expand in these countries and rest of the continent, there needs to be public–private partnerships fostered, integrated policies, political will as well as effective institutional frameworks.

1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the greatest long-term challenges that mankind is and will continue to experience (Steffen et al. Citation2007; McDowell et al. Citation2019). Human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels and massive industrialisation have been responsible for the increased greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere (Szulczewski et al. Citation2012). The increased release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere has resulted in climate change causing irrevocable impacts on the planet (Busby et al. Citation2014). These impacts have been widely observed on all sectors of the economy, society and environment (Skogen et al. Citation2018). Failure to address these issues, climate change will continue manifesting itself further through adverse impacts on a global level (Andric et al. Citation2019).

Climate change is undeniably one of the most pressing challenges and over the past decades various climate conferences have taken place to address this (Figueres & Streck Citation2009; Tobin et al. Citation2018). One of the most notable conferences established in the mid 1990s within the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was the Kyoto Protocol (Condor et al. Citation2011). The aim of the Protocol was to ensure legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions (Almer & Winkler Citation2017). The Conference of the Parties (COP) has been at the forefront of these climate negotiations with the most notable conference being the 21st COP held in 2015 where the Paris Agreement was adopted (Figueres Citation2016). This agreement was considered historic as 195 countries unanimously agreed to limit global temperatures well below 2°C (Figueres Citation2016). In order to achieve this global goal, climate investments are critical as countries need to make transformational changes to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and transition towards a low-carbon society and economy (Hainaut & Cochran Citation2018).

It has been argued that developing regions are more likely to be the worst impacted by climate change (Filho et al. Citation2018). For example, Africa has been identified as one of the most vulnerable as it is already climatically stressed and climate change is expected to exacerbate this (Dionne & Horowitz Citation2016). This view has further been iterated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2018 Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. The report highlighted how an increase in global temperatures would be disastrous for Africa as this could be twice the increase in temperatures on the continent (IPCC Citation2018). Africa’s problems are further worsened by weak institutions to effectively deal with climate change as weak institutions decrease the capacity and resilience of populations to cope with the impacts of climate change (Bisaro et al. Citation2018).

Climate challenge in Africa is complex because billions of dollars investments are required and most African countries are highly dependent on climate finance from developed countries (Bowman & Minas Citation2019). The Climate Funds Update 2018 report identified the Green Climate Fund (GCF) as one of the biggest multilateral climate fund for several African countries (Fonta et al. Citation2018). However, there are challenges that some of these countries have faced in accessing these finances. Fonta et al. (Citation2018) highlight how the Country Readiness Programme which is considered a priority of the GCF has witnessed only 19 out of 54 African countries having the institutional capacity and proper systems in place to access funds and resources. To further illustrate this, the World Resources Institute (Citation2019) highlighted how countries specifically in West Africa such as Senegal and Sierra Leone experienced challenges in accessing climate funds for adaptation and mitigation projects. This is due to a lack of a comprehensive budget on how funds should be distributed and utilised for various climate projects. Other hindrances identified included the lack of stakeholder engagement between public and private sectors, incoherent policies as well as weak government mandates. All these challenges in accessing climate finance emphasise the importance of African countries to explore new finance mechanisms, such as green bonds, if their commitments to the Paris Agreement is to be achieved (Gianfrate & Peri Citation2019). New finance mechanisms can provide opportunities for African countries to mobilise large amounts of private capital and investments that are readily available and accessible (Chirambo Citation2016). This is supported by the African Development Bank who argue that innovative investment strategies for climate change are rapidly increasing on the continent and provide the opportunity for African countries to not be fully dependent on one source of climate finance (AfDB Citation2018). One of these finance mechanisms has been green bonds which are fast becoming a viable financing option on the continent for investments in large-scale environmental projects (Guha Citation2019).

The green bond market has proven to be an innovative finance mechanism to mobilise private capital for climate projects (Pham Citation2016; Glomsrod & Wei Citation2018). Global green bond issuances are rapidly increasing in both developed and developing countries due to investor awareness on the impacts of climate change (Glomsrod & Wei Citation2018). It is important to note that the green bond market is much smaller in terms of overall size in developing countries however; there are initiatives which are being taken by developing country governments to ensure that the market continues to expand (Banga Citation2019). The Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), which is one of the leading organisations in climate and green bonds, identified an increase in issuances between the years of 2018 and 2019 from emerging markets such as China, Brazil and India (IFC Citation2018; CBI Citation2019a). It was further highlighted how the growth of green bonds from these emerging markets has been attributed to the various initiatives by the CBI and these countries to enable and facilitate the expansion of the green bond market (CBI Citation2019b).

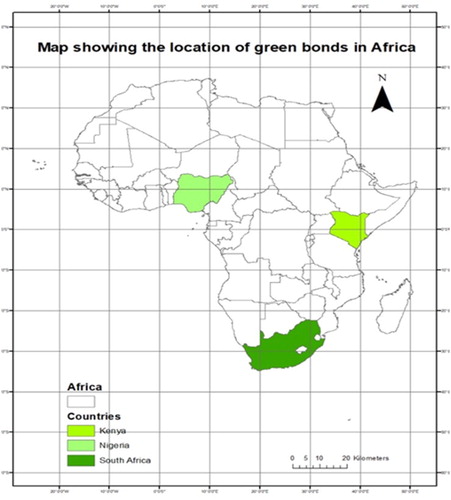

In Africa, the green bond market has been active in the economic hubs of Africa (London Stock Exchange Citation2018). It is because of this that this paper presents an analysis of the green bond market in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa as well as the challenges and opportunities that exist for its growth on the continent. This paper also aims to address the gap in knowledge of green bonds in Africa.

2. Green bonds: A new source of climate finance

Combating climate change requires more finance and resources than governments alone cannot provide. Green investments for climate projects have presented several business opportunities and further allowed investors to adapt their business models to not only have financial value but environmental values in an effort to protect the planet (Doval & Negulescu Citation2014; Taghizadeh-Hesary & Yoshino Citation2019). One of the most promising and innovative investment opportunities that have emerged over the years has been green bonds in comparison to blue and sustainability bonds (Paranque & Revelli Citation2019). These bonds have been described as a key solution to help finance many countries transition towards a low-carbon society and economy (ICMA Citation2019).

According to Banga (Citation2019) there is a growing consensus on what green bonds are and what they are intended to do although there is no standard definition that currently exists. The International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) defines a green bond as funds ‘raised to finance or re-finance green projects, assets or business activities’ (Citation2015: 1). While the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) defines a green bond as not being different from a conventional bond except that the proceeds are ‘invested in projects that generate environmental benefits’ (Citation2019: 1). These different definitions have similarities in what a green bond is even though there is no universal definition. For the purpose of this paper, the World Bank definition of a green bond will be adopted which is defined as ‘a debt security that is issued to raise capital specifically to support climate-related environmental projects’ (World Bank Citation2015: 23).

The phenomenal growth of the green bond market has been attributed to increasing climate-awareness from investors about the benefits and impacts of green investments (Pham Citation2016). The development of the green bond market is evident in developed regions with the top issuers being in Europe and the United States (Reboredo Citation2018). Although emerging markets from Asia and Latin America have also demonstrated the huge potential of this market (CBI Citation2019b). These include countries such as China, India, Brazil, Mexico and Malaysia (CBI Citation2019b). The CBI (Citation2019b) reported an increase in green bond issuances due to policies and frameworks within emerging markets that are supporting green bond market infrastructure (S&P Global Citation2019).

However, there are factors that continue to act as barriers to further development of the green bond market in developing regions (Nanayakkara & Colombage Citation2019). These include high transaction costs associated with green bond issuance, the lack of incentives as well as weak government policies and mandates have acted as key barriers to market growth, especially in regions such as Africa (Moid Citation2017).

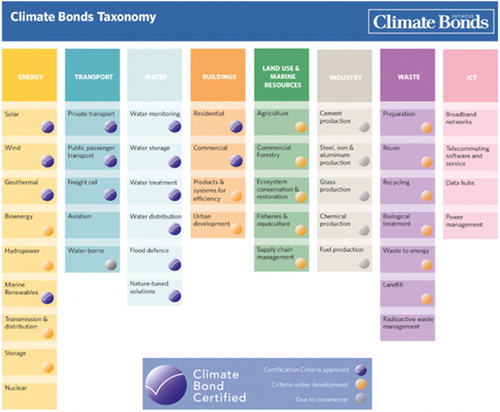

The establishment of the Green Bond Principles (GBP) have been considered an important component of green bonds and can be a potential solution to some of the barriers that the market has had, thus far. The GBP can be described as voluntary guidelines and processes for the issuance of green bonds to promote transparency and integrity in the green bond market (ICMA Citation2018). There are four key components of the GBP (ICMA Citation2018). First, there is the use of green bond proceeds where the GBP recognise broad categories of the most commonly used projects for green bonds (ICMA Citation2018). Some of these common environmental projects for the green bonds are also highlighted under the CBI taxonomy in which the GBP provides space for these projects to be highlighted (CBI Citation2019a) (). However, it is important to note that the GBP and the CBI taxonomy are the not the same thing.

Figure 1. The different categories and projects under the CBI taxonomy. Source: Climate Bonds Initiative.

Second, there is the process for project evaluation and selection in which an external review is recommended to assist issuers with project evaluation and green certification (ICMA Citation2018). The issuers of green bonds are expected to communicate to stakeholders and investors regarding how the chosen green projects will have environmental benefits as well as how potential environmental and social risks will be managed (ICMA Citation2018).

Third, there is the management of proceeds in which issuers are expected to track the net proceeds of the green bond for the entire period (ICMA Citation2018). To further ensure a high level of transparency, the GBP outline the use of a third party verifier or an auditor to verify and track the allocation of funds to ensure issues around corruption and mismanagement of funds are adequately dealt with (ICMA Citation2018).

The last component is reporting where issuers are encouraged to make information readily available on the use of proceeds (ICMA Citation2018). It is also expected from issuers that information be communicated in a manner that is well understood (ICMA Citation2018). Overall, the GBP are there to provide transparency and accountability and it is hoped that as the market expands and evolves that guidelines and processes become strengthened. In addition, in a policy brief by the CBI notes how in areas of financial activities, such as economic hubs, this provides an opportunity for market participants to develop local green bond markets where the GBP can further be developed and integrated (CBI Citation2019b). This allows for the development of a sustainable green bond market where there is regulation and guidelines on a local and international scale.

3. Economic hubs

This paper provides an analysis of green bonds in the economic hubs of Africa and hence it is important to define what an economic hub is and the different ways it has been theorised in literature. The theory of economic hubs is best understood within the context of economic geography. Malecki (Citation2017) highlights how economic geography focuses on commercial and economic activities within geographical areas. Economic hubs are specific places and spaces where there is a concentration of economic activities which result in a higher capital output (Malecki Citation2017). This view is further supported by Poon et al (Citation2015) who highlight how an economic hub is where there is a geographical concentration of wealth through the location of financial services or multinational companies. This is further illustrated by Hayter & Patchell (Citation2015) who discuss how economic hubs contribute to the broader global economy due to local production, value chains and networks that emerge from different sectors located in a specific area.

On the other hand, Warf (Citation2015) is of the view that in economic geography, economic hubs should be analysed on the dichotomy between society and the economy. The author argues that an economic hub is not just about the high capital output of certain sectors but is about social activities that occur in urban economies (Warf Citation2015). This is further illustrated by Penco (Citation2015) who argues that economic hubs contribute to a knowledge economy where intellectual contributions become a stimulus for innovation. Furthermore, human capital has also been considered as an important factor in economic hubs. Fertig et al (Citation2009) argue that an economic hub is a network of human capital where the most highly skilled individuals contribute to the flows of knowledge and information.

In addition, by drawing on the concept of globalisation this has also been considered as important in economic hubs. Globalisation has been referred to the interconnectedness of the world through global networks of capital flows, trade and technology (Harvey Citation1995). Chaminade & Vang (Citation2008) argue that cities have become important as hubs of economic activities due to globalisation. This is because of the continuous movement of goods and services, diverse economies and development which globalisation has spurred on economic hubs across the world (Chaminade & Vang Citation2008).

Africa’s growth and development has been astounding with emerging markets showing great potential (Asongu Citation2017). It is important to note that for this paper, the three countries being Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa use different criteria for what constitutes as an economic hub. First, Kenya is considered as an economic hub due to the country being one of the most economically advanced and industrialised countries in East Africa (UNCTAD Citation2018). This is because of the continuous growth the country has had with the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growing to 5.7% in 2018, superseding all the other countries in the region (World Bank Citation2018). It is also one of the leading manufacturing and trade hubs in East Africa (McKinsey Citation2015). Furthermore, Kenya’s thriving entrepreneurial workforce has also contributed to the country being a leading economic hub (Pedo et al. Citation2018).

Second, Nigeria is considered one of the biggest economic hubs in West Africa due to the petroleum industry which is the biggest on the continent (Olofin et al. Citation2014; KPMG Citation2018). According to the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 2018 Nigeria was amongst one of the largest petrol importers in the world (OPEC Citation2016). The abundance of oil has catapulted the country to be one of the biggest economies in the West African region (Kemi Citation2019).

Third, South Africa’s mineral-energy complex has catapulted the country to be a leading economic hub in Africa. The mining sector has generated huge wealth for the country with an abundance of valuable resources such as platinum, gold, diamond and coal. In addition, the country’s agricultural sector is the biggest and most advanced sector on the continent (Scholvin & Draper Citation2012). Through the use of agro-processing, this sector has created profitable opportunities for the local economy and international investors (Greyling et al. Citation2015; Senyolo et al. Citation2018). Recently, over the past ten years, South Africa has grown towards a knowledge economy hub where a greater focus has been on ICT technology and e-commerce (Blankley & Booyens Citation2010).

4. Methodological considerations

This study is qualitative in nature and is based on case study research. Baxter & Jack (Citation2008: 544) describe a case study as ‘an approach to research that facilitates exploration of a phenomenon within its context using a variety of data sources’. A key advantage of using case studies is to explore phenomena or situations where little is known about (Baxter & Jack Citation2008). Hence, this paper presents case study experiences of green bonds in Africa drawn from the three different countries of Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa in which these countries are also considered the economic hubs of the continent.

The paper relied on secondary data which was collected on green bond issuances in Africa. An extensive web-based search using Google was conducted. Keywords used during the web-based search included ‘Green bonds Africa’, ‘Green bond issuances Africa’ as well as ‘Green bond market Africa’. Upon getting results from the search it was found that the green bond market was active in only three countries being Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa which were also described as the economic hubs of the continent. To find detailed information on green bonds in these countries, the web-based search became more refined using words such as ‘Green bonds Kenya’, ‘Green bonds Nigeria’ as well as ‘Green bonds South Africa’.

Published data were available for all the three countries from private companies, government, stock exchanges, media reports as well as reports and publications from different organisations. From Kenya, published data was available from the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE), FSD Africa, the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) and the Kenyan Green Bonds Programme. Second, from Nigeria published data was available from the Climate Bonds Initiative, the Nigerian Stock Exchange, the Debt Management Office Nigeria, Access Bank and Moody’s. Lastly, in South Africa, information was found from the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, GrowthPoint Properties, Nedbank, the International Financial Corporation (IFC), the City of Cape Town, the City of Johannesburg as well as the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC).

The researchers did not come across any academic literature that was published on the green bond market specifically on Africa during the data collection period.

5. Green bonds in the economic hubs of Africa

In the context of Africa, recent trends and developments of the green bond market have been observed in the three economic hubs and it is also where several issuances of green bonds have occurred ().

5.1. Case study: Kenya

The government of Kenya has set ambitious plans for change in order to transition towards a low-carbon society and this has been reflected in key policies such as the Green Economy Strategy and Implementation Plan (GESIP) of 2016–2030 (GESIP Citation2016). A significant aspect within the GESIP is identifying green finance mechanisms such as green bonds to support the country’s green growth path (GESIP Citation2016). As a result of this, the Kenyan Green Bonds Programme (GBPK) was launched in March 2017 with the aim to support the development of a domestic green bond market (GBPK Citation2017).

A central component of the GBPK was a multi-stakeholder partnership (GBPK Citation2017). This included the Central Bank of Kenya, FSD Africa, the CBI, Nairobi Securities Exchange, Kenyan Bankers Association, Capital Markets Authority, FMO Dutch Development Bank, International Finance Corporation (IFC) as well as the Kenyan National Treasury (GBPK Citation2017). The outcome of this partnership resulted in an advisory committee established from national treasury and parliament to influence new policy incentives and regulations to attract investors (GBPK Citation2017). In the private sector, structures were also implemented by the Kenyan National Treasury and the IFC to create awareness and knowledge with market participants on green bonds (GBPK Citation2017).

The first corporate green bond was issued in August 2019 worth 4.26 billion by Acorn Holdings which is a real estate development firm (Reuters Citation2019). The proceeds were allocated to build environmentally friendly student accommodation (Reuters Citation2019). This green bond issuance demonstrates the effectiveness of multi-stakeholder partnerships in creating platforms to achieve environmental objectives (Reuters Citation2019). This is further supported by the Kenyan Capital Markets Regulator who highlighted how the East African community could leverage from the Kenyan experience on the platforms created to advance an effective green bond market (Reuters Citation2019).

However, Magale (Citation2018) is of the view that further work still needs to be done in developing the Kenyan green bond market. Magale (Citation2018) argues that resources need to be directed to local Kenyan market participants to develop skills and expertise on green. Furthermore, the author highlights that the Nairobi Securities Exchange is required to establish robust reporting guidelines to enforce compliance for issuers and hence maintain the integrity of the market (Magale Citation2018). This is supported by the CBI (Citation2019b) who argues that local stock exchanges can play an important role in ensuring that issuers adhere to the green bond principles.

5.2. Case study 2: Nigeria

One of the most significant aspects of Nigeria’s climate change policies has been the need to diversify funds and access private capital to invest in the country’s low-carbon transition (Dioha et al. Citation2019). In 2016 the Federal Government of Nigeria identified green bonds as a form of sustainable finance where the Nigerian Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Finance collaborated in setting up the Nigerian Green Bonds Framework (CBI Citation2018). Furthermore, events such as the Nigerian green bond week, investment seminars as well as massive media coverage created platforms to increase awareness from other stakeholders (CBI Citation2018). These stakeholders included the CBI, the Nigerian local investment community, Access Bank, FSD Africa as well as FMDQ OTC Securities Exchange (NSE Citation2018).

As a result of this the first green bond was issued in 2017 by the Federal government of Nigeria worth N10.6 billion (Lexology Citation2017). The issuance of the bond was also highly supported by the Nigerian investment community as a wide range of investors from commercial banks, asset management firms and pension groups also invested in the green bond. The proceeds of the bonds were utilised in funding three green projects being the Afforestation Project, the Energising Education Project as well as the Rural Electrification Project (Lexology Citation2017). The Federal Government of Nigeria also highlighted how these projects were specifically chosen as they align with the Sustainable Development Goals (Elum & Momodu Citation2017). In addition, the CBI rated the country with a positive assessment with regards to how the different projects were implemented (CBI Citation2018). This was also supported by Moody’s in which Nigeria was rated with GB 1 which is regarded as excellent (Moody’s Citation2017b).

The success of the first green bond issued in Nigeria increased investor confidence from local and international investors (ESI Africa Citation2019). In 2019, Access Bank which is one of the biggest commercial banks in Nigeria issued the country’s second green bond (CBI Citation2019c). The bank also became the first certified corporate green bond in Africa to issue a green bond (CBI Citation2019c). The proceeds of the bond would be allocated for water infrastructure and solar energy generation facilities (CBI Citation2019c). Due to the increased investor interest, various departments and institutions such as the Nigerian Stock Exchange have issued regulations on the issuance of green bonds (NSE Citation2018). These regulations have incorporated the Green Bond Principles and are aimed at promoting integrity within the local green bond market in Nigeria (Lexology Citation2017).

5.3. Case study: South Africa

The South African government has stated its commitment to combating climate change by developing key climate change policies in the past decade. These include the National Climate Change Response Policy (NCCRP Citation2011), the National Climate Change Response White Paper (Citation2011) as well as South Africa’s draft National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (Citation2019). In order to enable the transition towards a low-carbon society, the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) and other key departments have highlighted the need to scale up financial resources from the private sector (DEFF Citation2011). One of these finance mechanisms has been green bonds which has gained significant interest from local and international investors in the past seven years to fund green projects in South Africa.

The first green bond in the country was issued in 2014 by the City of Johannesburg (COJ) worth R1.5 billion (COJ Citation2014). The proceeds of the bond were allocated to fund green projects such as low-carbon transport as well as energy saving measures for residents like solar water heating (COJ Citation2014). The success of this green bond resulted in COJ being acknowledged at the Paris Agreement for tackling climate change as well as receiving the C40 Cities Award for the green bond (COJ Citation2014).

In 2017, the City of Cape Town became the second city in the country to issue a green bond. This was also the first green bond in the country to be listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) green segment worth R1 billion (JSE Citation2017). There was increased investor appetite over this green bond because of the Invest Cape Town Initiative which brought together a range of stakeholders such as the CBI, Rand Merchant Bank, City of Cape Town, the Cape Chamber of Commerce as well as international investors. The proceeds of the bond were allocated to water management, coastal structures as well as other projects in line with the city’s climate change strategy (CBI Citation2017). This green bond was also successful as it was rated by Moody’s with a GB1 rating which is considered excellent and the City of Cape Town was also awarded ‘Green Bond of the Year – local authority’ by the Environmental Finance Green Bond Awards in 2018 (Moody’s Citation2017a; ESI Africa Citation2018).

In addition, a few green bonds have also been issued from the South African private sector. This has largely been attributed to the JSE’s green bond segment which has allowed investors to contribute in raising capital for sustainable and environmental projects. GrowthPoint Properties was one of the first South African real estate companies in 2018 to issue out a green bond on the JSE of R1 billion in which proceeds were allocated to energy efficiency and green office buildings (GrowthPoint Properties Citation2018). Furthermore, in 2019, Nedbank became the first corporate bank in the country to issue out a green bond worth R1.7 billion and proceeds were allocated to renewable energy projects in the country (JSE Citation2019).

6. Measures to accelerate the green bond market

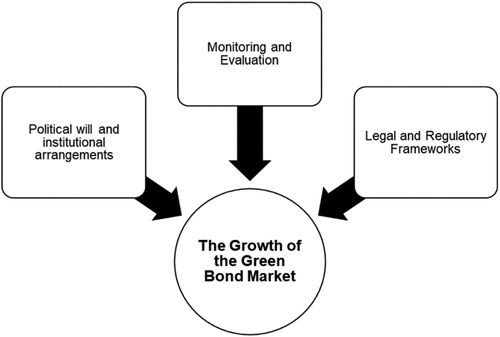

It is evident that there is huge potential for the green bond market to increase on the African continent. However, measures need to be in place to ensure that the market is rooted in proper frameworks and systems (). First, there needs to be legal and regulatory frameworks in place to ensure that the green bond market operates in a system where there is transparency and accountability from issuers.

Figure 3. Factors that can influence the growth of the Green Bond market in Africa. Source: Authors.

Second, there is a need for continuous monitoring and evaluation of the green bond market on the continent to determine investor behaviour and impact evaluation. This would enhance transparency and accountability which is very important for the integrity of the green bond market and would prevent issues such as greenwashing.

Third, in order for the green bond market to expand there is a need for political will and proper institutional arrangements. There also needs to be public and private partnerships fostered as well as policies implemented that guide the green bond market. This has already been witnessed with the African Development Bank (AfDB) Green Bond programme which was established to help facilitate green growth through financing eligible green projects (AfDB Citation2013). Similar strategies can be applied for the three countries as well as other African countries embarking on green bonds in the future.

7. Conclusion: The future path of green bonds in Africa

There are a number of important policy implications which should be considered for the development of the green bond market in Africa. The introduction of government policies such as tax incentives on green bonds should be implemented. This can enable green bonds to become more attractive to investors and enable issuers to get green bonds at a lower interest rate. For example, the government of China introduced a range of tax incentives, supportive policies as well as regulatory frameworks. This highlights the proactive approach that China took as a developing country which African countries can draw from.

African governments should also have policies which promote increased awareness and participation of green bonds. It is important for all market participants to have an understanding of the benefits that green bonds can have in achieving climate goals. With enhanced knowledge and understanding of the green bond market in Africa, this can also enable innovation within this space to further create a pool of new investors. For example, India introduced policies which engaged with the wider financial community on green bonds. This is another example of a developing country making great strides in the green bond market and this can also be applied by African countries.

There should also be established green bond principles and guidelines that are incorporated in the green bond market in Africa. This promotes integrity of the market but also ensures transparency and accountability for issuers. Every African country should implement a green bond segment in the local stock exchanges which are set at international best practice to further promote green listing rules and green issuances. Key lessons can be drawn from the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) in South Africa which has an established Green Bond Segment that has contributed to promoting the integrity of the green bond market in the country.

If all these factors are considered, the green bond market has the potential to increase on the continent. In addition, African countries can benchmark best practices and draw key lessons from other developing countries, such as China and India, on green bond market development experiences. There are valuable lessons which can be learnt and applied not only for Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa but for other African countries interested in being involved in the green bond market.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- African Development Bank (AfDB), 2013. At the center of Africa’s transformation: Strategy for 2013–2022. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Policy-Documents/AfDB_Strategy_for_2013%E2%80%932022_-_At_the_Center_of_Africa%E2%80%99s_Transformation.pdf Accessed 25 May 2019.

- African Development Bank (AfDB), 2018. Green bond programme: Eligible green projects. https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/green-bonds-program/ Accessed 25 May 2019.

- Almer, C & Winkler, R, 2017. Analysing the effectiveness of international environmental policies: The case of the Kyoto Protocol. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 82, 125–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2016.11.003

- Andric, I, Koc, M & Al-Ghamdi, SG, 2019. A review of climate change implications for built environment: Impacts, mitigation measures and associated challenges in developed and developing countries. Journal of Cleaner Production 211, 83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.128

- Asongu, SA, 2017. Assessing marginal, threshold, and net effects of financial globalisation on financial development in South Africa. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 40, 103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mulfin.2017.05.003

- Banga, J, 2019. The green bond market: A potential source of climate finance for developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment 9(1), 17–32. doi: 10.1080/20430795.2018.1498617

- Baxter, P & Jack, S, 2008. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report 13(4), 544–59.

- Bisaro, A, Roggero, M & Villamayor-Tomas, S, 2018. Institutional analysis in climate change adaptation research: A systematic literature review. Ecological Economics 151, 34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.016

- Blankley, WO & Booyens, I, 2010. Building a knowledge economy in South Africa. South African Journal of Science 106, 1–6. doi: 10.4102/sajs.v106i11/12.373

- Bowman, M & Minas, S, 2019. Resilience through interlinkage: The green climate fund and climate finance governance. Climate Policy 19(3), 342–53. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2018.1513358

- Busby, JW, Cook, KH, Vizy, EK, Smith, TD & Bekalo, M, 2014. Identifying hot spots of security vulnerability associated with climate change in Africa. Climatic Change 124, 717–31. doi: 10.1007/s10584-014-1142-z

- Chaminade, C & Vang, J, 2008. Globalisation of knowledge production and regional innovation policy: Supporting specialised hubs in the Bangalore software industry. Research Policy 37, 1684–96. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2008.08.014

- Chirambo, D, 2016. Moving past the rhetoric: Policy considerations that can make Sino-African relations to improve Africa’s climate change resilience and the attainment of the sustainable development goals. Advances in Climate Change Research 7, 253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.accre.2016.11.002

- City of Johannesburg, 2014. Joburg Pioneers Green Bond. https://www.joburg/org.za/media_/Newsroom/Pages/2014%20Articles/Joburg-pioneers-green-bond.aspx Accessed 15 June 2019.

- CBI (Climate Bonds Initiative), 2017. City of Cape Town Green Bond. https://www.climatebonds.ney/certification/city-of-cape-town Accessed 26 May 2019.

- CBI (Climate Bonds Initiative), 2018. Lagos Launch: Nigeria Green Bond Market Development Program: New initiative to boost African Green Finance. https://www.climatebonds.net/050616-lagos-launch-nigeria-green-bond-market-development-program-new-initiative-boost-african Accessed 12 November 2019.

- CBI (Climate Bonds Initiative), 2019a. Green Bonds market summary – H1 2019. https://www.climatebonds.net/resources/reports/green-bonds-market-summary-h1-2019. Accessed 24 February 2020.

- CBI (Climate Bonds Initiative), 2019b. Latin America and Caribbean green finance: Huge potential across the region. https://www.climatebonds.net/2019/09/latin-america-caribbean-green-finance-huge-potential-across-region Accessed 28 June 2019.

- CBI (Climate Bonds Initiative), 2019c. Nigeria: Access Bank 1st Certified Corporate Green Bond in Africa: Leadership in Green Finance. https://www.climatebonds.net/2019/04/nigeria-access-bank-1st-certified-corporate-green-bond-africa-leadership-green-finance Accessed 10 November 2019.

- Condor, J, Unatrakarna, D, Asghari, K & Wilson, M, 2011. Current status of CCS initiatives in the major emerging economies. Energy Procedia 4, 6125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2011.02.620

- DEFF (Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries), 2011. Financing climate change. https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/financing_climate_change.pdf Accessed 15 November 2019.

- Dioha, MO, Emodi, NV & Dioha, EC, 2019. Pathways for low carbon Nigeria in 2050 by using NECAL2050. Renewable Energy Focus 29, 63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ref.2019.02.004

- Dionne, KY & Horowitz, J, 2016. The political effects of agricultural subsidies in Africa: Evidence from Malawi. World Development 87, 215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.06.011

- Doval, E & Negulescu, O, 2014. A model of green investments approach. Procedia Economics and Finance 15, 847–52. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00545-0

- Elum, ZA & Momodu, AS, 2017. Climate change mitigation and renewable energy for sustainable development in Nigeria: A discourse approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 76, 72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.040

- ESI Africa, 2018. City of Cape Town scoops green bond of the year. https://www.esi-africa.com/industry-sectors/business-and-markets/city-of-cape-town-scoops-green-bond-of-the-year/ Accessed 15 November 2019.

- ESI Africa, 2019. Nigeria moves to its second green bond issuance. https://www.esi-africa.com/industry-sectors/finance-and-policy/nigeria-moves-to-its-second-green-bond-issuance/ Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Fertig, M, Schmidt, CM & Sinning, MG, 2009. The impact of demographic change on human capital accumulation. Labour Economics 16, 659–68. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2009.08.005

- Figueres, C, 2016. The power of policy: Reinforcing the Paris trajectory. Global Policy 7(3), 448–9. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12369

- Figueres, C & Streck, C, 2009. The evolution of the CDM in a post-2012 climate agreement. The Journal of Environment and Development 18(3), 227–47. doi: 10.1177/1070496509337908

- Filho, WL, Balogun, AL, Ayal, DY, Bethurem, EM, Murambadoro, M, Mambo, J, Taddese, H, Tefera, GW, Nagy, GJ, Fudjumdjum, H & Mugabe, P, 2018. Strengthening climate change adaptation capacity in Africa – case studies from six major African cities and policy implications. Environmental Sciences and Policy 86, 29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.05.004

- Fonta, WM, Ayuk ET & van Huysen, T, 2018. Africa and the green climate fund: Current challenges and future opportunities. Climate Policy 18(9), 1210–25. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2018.1459447

- GBPK (Green Bonds Programme Kenya), 2017. Green Bonds Kenya. https://www.greenbondskenya.co.ke/ Accessed 5 June 2019.

- GESIP (Green Economy Strategy and Implementation Plan), 2016. Kenya Green Economy Strategy and Implementation Plan 2016–2030. http://www.greengrowthknowledge.org/national-documents/kenya-green-economy-strategy-and-implementation-plan-2016-2030 Accessed 5 June 2019.

- Gianfrate, G & Peri, M, 2019. The green advantage: Exploring the convenience of issuing green bonds. Journal of Cleaner Production 219, 127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.022

- Glomsrod, S & Wei, T, 2018. Business as unusual: The implications of fossil divestment and green bonds for financial flows, economic growth and energy market. Energy for Sustainable Development 44, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2018.02.005

- Greyling, JC, Vink, N & Mabaya, E, 2015. South Africa’s agricultural sector twenty years after democracy (1994 to 2013). Professional Agricultural Workers Journal 3(1), 1–14.

- GrowthPoint Properties, 2018. Appendix A: GrowthPoint Properties Green Bond Framework. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://growthpoint.co.za/environmental-sustainability/green-bond Accessed 5 May 2019.

- Guha, A, 2019. Green Bonds: Key to Fighting Climate Change? ORF Issue Brief No. 321. 1–13. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336881064_Green_Bonds_Key_to_Fighting_Climate_Change/link/5db88459a6fdcc2128eb920b/download Accessed 12 November 2019.

- Hainaut, H & Cochran, I, 2018. The Landscape of domestic climate investment and finance flows: Methodological lessons from five years of application in France. International Economics 155, 69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.inteco.2018.06.002

- Harvey, D, 1995. Globalisation in question. Journal of Economics, Culture and Society 8(4), 1–17.

- Hayter, R & Patchell, J, 2015. Economic geography: An institutional approach. 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- ICMA (International Capital Markets Association), 2015. Green Bond Principles, 2015. https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/GBP_2015_27-March Accessed 15 July 2019.

- ICMA (International Capital Markets Association), 2018. Green Bond Principles: Voluntary process guidelines for issuing Green Bonds. https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/June-2018/Green-Bond-Principles---June-2018-140618-WEB.pdf Accessed 24 February 2020.

- ICMA (International Capital Markets Association), 2019. Green, Social and Sustainability bonds. https://www.icmagroup.org/green-social-and-sustainability-bonds/ Accessed 10 November 2019.

- IFC (International Finance Corporation), 2018. Emerging Market Green Bonds Report 2018: A consolidation year paving the way for growth. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/9e8a7c68-5bec-40d1-8bb4-a0212fa4bfab/Amundi-IFC-Research-Paper-2018.pdf?MOD=AJPERES Accessed 12 November 2019.

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), 2018. Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C. https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/ Accessed 5 May 2019.

- JSE (Johannesburg Stock Exchange), 2017. JSE launches Green Bond segment fund low-carbon projects. https://www.jse.co.za/articles/Pages/JSE-launches-Green-Bond-segment-to-fund-low-carbon-projects.aspx Accessed 24 February 2020.

- JSE (Johannesburg Stock Exchange), 2019. Nedbank Green Bond listed on the JSE. https://www.jse.co.za/articles/Pages/Nedbank-Limited-lists-a-Green-Bond-on-the-Johannesburg-Stock-Exchange-(JSE).aspx Accessed 25 May 2019.

- Kemi, AO, 2019. Nigeria’s economy challenges: Causes and way forward. Journal of Economics and Finance 10(2), 78–82.

- KPMG, 2018. Nigeria’s oil and gas outlook and Nigerian content. https://home.kpmg/ng/en/home/insights/2018/11/The-KPMG-Guide-Nigeria%E2%80%99s-Oil-and-Gas-Outlook-Nigerian-Content.html Accessed 27 May 2019.

- Lexology, 2017. Green bonds and the emergence of sustainable finance in the Nigerian capital market. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=c402f0e6-471b-41b8-b161-40feabf01804 Accessed 5 May 2019.

- London Stock Exchange, 2018. London Stock Exchange Africa Advisory Group: Developing the green bond market in Africa. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://www.lseg.com/documents/africa-greenfinancing-mwv10-pdf&ved Accessed 26 June 2019.

- Magale, E, 2018. Experts’ opinion on challenges facing the development of green bonds on the Nairobi Securities Exchange. Masters thesis, University of Cape Town.

- Malecki, EJ, 2017. Real people, virtual places, and the spaces in between. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 58, 3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.seps.2016.10.008

- McDowell, G, Huggel, C, Frey, H, Wang, FM, Cramer, K & Ricciardi, V, 2019. Adaptation action and research in glaciated mountain systems: Are they enough to meet the challenge of climate change? Global Environmental Change 54, 19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.012

- McKinsey, 2015. East Africa: The next hub for apparel sourcing? https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/east-africa-the-next-hub-for-apparel-sourcing Accessed 10 August 2019.

- Moid, S, 2017. Green bonds: Country experiences, challenges and opportunities. Rajagiri Management Journal 11(2), 1–17.

- Moody’s, 2017a. Moody's Assigns GB1 (Excellent) Green Bond Assessment to the City of Cape Town Green Notes. https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-Assigns-GB1-Excellent-Green-Bond-Assessment-to-the-City–PR_368194 Accessed 19 November 2019.

- Moody’s, 2017b. Moody's Investors Service Assigns GB1 (Excellent) Green Bond Assessment to the Government of Nigeria's Green Notes. https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-Investors-Service-Assigns-GB1-Excellent-Green-Bond-Assessment-to–PR_375611 Accessed 19 November 2019.

- Nanayakkara, M & Colombage, S, 2019. Do investors in green bond market pay a premium? Global evidence. Applied Economics 10, 159–61.

- National Climate Change Response White Paper, 2011. https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/legislations/national_climatechange_response_whitepaper.pdf Accessed 12 June 2019.

- Nigerian Stock Exchange, 2018. Green Bonds. http://www.nse.com.ng/products/debt-instruments/green-bonds Accessed 19 November 2019.

- Olofin, SO, Olubusoye, OE, Mordi, CNO, Salisu, AA, Adeleke, AI, Orekoya, SO, Olowookere, AE & Adebiyi, MA, 2014. A small macroeconometric model of the Nigerian economy. Economic Modelling 39, 305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2014.03.003

- OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries), 2016. OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/ASB2016.pdf Accessed 10 June 2019.

- Paranque, B & Revelli, C, 2019. Ethico-economic analysis of impact finance: The case of green bonds. Research in International Business and Finance 47, 57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.12.003

- Pedo, MO, Kabare, K & Makori, M, 2018. Effects of public private partnerships frameworks on performance of public private partnership road projects in Kenya. The Strategic Journal of Business and Change Management 5(1), 60–87.

- Penco, L, 2015. The development of the successful city in the knowledge economy: Toward the dual role of consumer hub and knowledge hub. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 6, 818–37. doi: 10.1007/s13132-013-0149-4

- Pham, L, 2016. Is it risky to go green? A volatility analysis of the green bond market. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment 6(4), 263–91. doi: 10.1080/20430795.2016.1237244

- Poon, JPH, Tan, GKS & Yin, W, 2015. Wage inequality between financial hubs and periphery. Applied Geography 61, 47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.12.023

- Reboredo, JC, 2018. Green bond and financial markets: Co-movement, diversification and price spillover effects. Energy Economics 74, 38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2018.05.030

- Reuters, 2019. Kenya approves issuance of first green bond. https://www.reuters.com/article/kenya-bonds-green/kenya-approves-issuance-of-first-green-bond-idUSL8N25B1TQ Accessed 15 November 2019.

- Scholvin, S & Draper, P, 2012. The gateway to Africa? Geography and South Africa’s role as an economic hinge joint between Africa and the world. South African Journal of International Affairs 19 (3), 381–400. doi: 10.1080/10220461.2012.740321

- Senyolo, MP, Long, TB, Blok, V & Omta, O, 2018. How the characteristics of innovations impact their adoption: An exploration of climate-smart agricultural innovations in South Africa. Journal of Cleaner Production 172, 3825–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.019

- Skogen, K, Helland, H & Kaltenborn, B, 2018. Concern about climate change, biodiversity loss, habitat degradation and landscape change: Embedded in different packages of environmental concern? Journal for Nature Conservation 44, 12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2018.06.001

- South Africa’s Draft National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, 2019. https://cer.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/DEA-Draft-climate-change-adaptation-strategy.pdf Accessed 12 June 2019.

- Steffen, W, Crutzen, PJ & McNeill, JR, 2007. The anthropocene: Are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 36, 614–21. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[614:TAAHNO]2.0.CO;2

- Szulczewski, M, MacMinn, CW, Herzog, HJ & Juanes, R, 2012. Lifetime of carbon capture and storage as a climate-change mitigation technology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 5185–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115347109

- S&P Global, 2019. S&P Ratings forecasts moderate green bond market growth in 2019. https://www.spsglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/trending/P9Lq4MCmw-HL6iMRUKgEHG2 Accessed 28 June 2019.

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F & Yoshino, N, 2019. The way to induce private participation in green finance and investment. Finance Research Letters 31, 98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2019.04.016

- Tobin, P, Schmidt NM, Tosun, J & Burns, C, 2018. Mapping states’ Paris climate pledges: Analysing targets and groups at COP21. Global Environmental Change 48, 11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.11.002

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), 2018. Economic Development in Africa Report 2018. https://unctad.org≥edar2018_ch6_en Accessed 7 June 2019.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), 2019. Green Bonds. https://www.sdfinance.undp.org/content/sdfinance/en/home/solutions/green-bonds/ Accessed 23 May 2019.

- Warf, B, 2015. Global cities, cosmopolitanism, and geographies of tolerance. Urban Geography 36(6), 927–46. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1067408

- World Bank, 2015. What are Green Bonds? http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/554231525378003380/publicationpensionfundservicegreenbonds201712-rev.pdf Accessed 25 May 2019.

- World Bank, 2018. Kenya Economic Update. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/766271538749794576/pdf/Kenya-Economic-Update-18-FINAL.pdf Accessed 19 November 2019.

- World Resource Institute, 2019. Multilateral Development Bank Climate Finance in 2018: The Good, the Bad and the Urgent. https://www.wri.org/blog/2019/06/multilateral-development-bank-climate-finance-2018-good-bad-and-urgent Accessed 7 June 2019.