ABSTRACT

The tourism sector is routinely offered as an option to grow employment in South Africa. Yet, questions need to be asked about the nature of employment in tourism, the state of education and skills training in the sector and its prospects for youth. Drawing on a national study, this paper interrogates tourism education and skills training issues in relation to youth employment and development. The findings reveal that youth in the sector find themselves in precarious employment: they typically have low-level skills, do not continue their education or training after being employed and have few career progression options. At the same time, a mismatch between the outcomes of education and skills training in tourism and the requirements of the industry come to the fore. Enhanced skills development and the creation of pathways for learning; labour market access and upward career progression are needed to advance youth in tourism.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a growing sector in South Africa, demonstrated by steady increases in tourism arrivals, expenditure and employment since the advent of democracy (Rogerson, Citation2007; Fourie & Santana-Gallego, Citation2013; Bhorat et al., Citation2018; Makumbirofa & Saayman, Citation2018). In 2017, the number of non-resident visitors amounted to 14 975 675, tourism employment stood at 722 013 and the sector’s contribution to the Gross Domestic Product was 2.8% (Stats SA, Citation2018). Tourism also accounts for the bulk of service exports (Rogerson, Citation2007; Fourie & Santana-Gallego, Citation2013; Bhorat et al., Citation2018; Visagie & Turok, Citation2019). The performance of the tourism sector needs to be contextualised in relation to the expansion of service sectors. Services comprise approximately two thirds of the South African economy and have been responsible for the lion’s share of employment growth over the last two decades (Bhorat et al., Citation2018; Rogerson, Citation2018).

Given its strong growth performance, contrasted against the relative decline of labour intensive sectors like mining, manufacturing and agriculture; tourism is routinely promoted as a strategic labour absorbing sector with low entry barriers (Altman, Citation2006; Black & Gerwel, Citation2014; Cichello et al., Citation2014; Bhorat et al., Citation2018; Visagie & Turok, Citation2019). Indeed, the potential of tourism has been emphasised in recent State of the Nation AddressesFootnote1 and also in the National Development and New Growth plans (Bhorat et al., Citation2018). Moreover, provincial and local economic development strategies have in recent years habitually underscored the economic potential of tourism for their areas (Rogerson, Citation2015).

The policy focus on tourism for job creation and poverty alleviation is important vis-à-vis high levels of unemployment in South Africa and tourism sustainability debates in the global South (Altman, Citation2006; Saarinen & Rogerson, Citation2014; Baum, Citation2015; Rogerson, Citation2015, Citation2018, Citation2020). In particular, youth unemployment remains a critical and growing concern. The latest employment figures reveal that while the overall unemployment rate of 29,0% is at its highest since the start of 2008, the youth (persons aged 15–34 years) unemployment rate amounts to a staggering 56,4% (Stats SA, Citation2019). In the context of unemployment and poverty, much is expected of education and training towards achieving socio-economic upliftment (Rogan, Citation2018). Indeed, Bhorat et al. (Citation2016) point to an overall skills-biased trajectory in South Africa: those who are better educated are more likely to find employment. This said, access to post-school education and training and also to the labour market by graduates remains overall constraints (Rogan, Citation2018).

Notwithstanding the number of jobs created in tourism, critical questions need to be asked about the nature of employment in tourism; sustainability and human development in the sector; and its prospects for youth. The literature indicates that, for the most part, tourism employment is low skilled and low paid; working conditions are often unfavourable; and career progression and job security are limited (Zampoukos & Ioannides, Citation2011; Baum, Citation2015; Baum et al., Citation2016; Tsangu et al., Citation2017). This evokes concerns about decent work in tourism which is at the heart of sustainability debates: the Sustainable Development Goal no. 8 advocates for full and productive employment and decent work for all. Tourism scholars bemoan the neglect of workplace and employment considerations in discourses on sustainability in tourism globally and also in South Africa (De Beer et al., Citation2014; Saarinen & Rogerson, Citation2014; Baum, Citation2015; Baum et al., Citation2016; Makumbirofa & Saayman, Citation2018). In fact, Rogerson (Citation2020) is of the view that tourism workplace issues, including a focus on employment, are the most weakly developed domain in the local tourism scholarship. This is a conspicuous gap in light of the ‘mushrooming literature on sustainable tourism in South Africa’ (Rogerson, Citation2020:13).

This paper makes a contribution to the literature on tourism employment and sustainably, from the South African perspective, by focussing on education and skills attainment vis-à-vis youth employment. In particular, employment trends in tourism with a focus on youth, the educational attainment and career progression of tourism workers, and education and skills training issues in tourism and hospitality are interrogated. This paper draws on a national study on human resource and skills development in tourism. This study was broad-based, combining secondary analysis with a tourism firm level survey and qualitative data from a number of stakeholder engagements. This paper makes a unique contribution as there is a dearth of research taking a broad view on either tourism skills and education, or youth employment, beyond isolated case studies (see Rogerson, Citation2020). Moreover, most analyses on either youth unemployment and/or education and training rely heavily on secondary data and/or quantitative analyses with limited qualitative insights for what is observed (Yu, Citation2013; Rogan, Citation2018; Grice, Citation2019).

The paper is structured as follows. Literature on youth employment and prospects with reference to tourism are provided in the second section. The third section outlines the methods. The findings are organised in two main sections: tourism employment and skills with an emphasis on youth (section four) and education and training issues (section five). A discussion with conclusions follows in section six.

2. Youth employment and prospects in tourism

In the view of sustainability debates, youth employment, not least in tourism, emerges as a global concern (Standing, Citation2010; Saarinen & Rogerson, Citation2014; Baum, Citation2015; Baum et al., Citation2016). Standing (Citation2011:65) underscores the overall precariousness of youth in terms of employment:

The world’s youth, more than 1 billion aged between 15 and 25, comprise the largest youth cohort in history, a majority in developing countries. The world may be ageing but there are a very large number of young people around, with much to be frustrated about … Youths have always entered the labour force in precarious positions, expecting to have to prove themselves and learn. But today’s youth are not offered a reasonable bargain. Many enter temporary jobs that stretch well beyond what could be required to establish ‘employability’’.

A common challenge faced by tourism graduates when they start out to find employment is a general lack of work experience; they accordingly find themselves under-employed, if employed at all (Marchante et al., Citation2007; Baum, Citation2015; Tsangu et al., Citation2017). The expectation is that with experience gained, graduates will over time be able to find better employment. Yet, under-employment commonly becomes permanent due to the general lack of career progression opportunities in the sector (Marchante et al., Citation2007; Baum, Citation2015). Therefore, employees often get ‘locked into’ low paying, precarious jobs even if they do have tourism qualifications. Marchante et al. (Citation2007:316) found in a study of 3,314 employees that there is no evidence that ‘overeducated workers have gained better jobs in other hotels and restaurants outside the current firm’ or that entry level jobs serve as ‘stepping stones’ to a future career in hospitality. Moreover, the tourism sector suffers from a low retention of graduates and young people typically exit the sector after a couple of years (De Beer et al., Citation2014; Baum, Citation2015; Mooney, Citation2016; Tsangu et al., Citation2017). Perceptions persist that tourism work is temporary, suited for students who will move onto other careers when completing their studies or reserved for migrants who will accept poor conditions and poor pay (Marchante et al., Citation2007; Mooney, Citation2016).

Concerns about the ‘servility’ of tourism work, accordingly, come to the fore in debates on workforce issues in the sector (Zampoukos & Ioannides, Citation2011; Baum et al., Citation2016; Mooney, Citation2016; Williamson, Citation2017). Historically, work in services has not been regarded as ‘labour’, that is not contributing to the physical production of industrial goods, and thus considered ‘unproductive’ by classical and political economists alike (see Standing, Citation2010). Conversely, Standing (Citation2010:6) remarks that: ‘Ironically, long before the end of the twentieth century a majority of people in industrial countries were doing “service jobs”’. However, the unionisation level of services workers, especially tourism and hospitality workers, have been low in comparison to those in traditional industrial sectors (Baum, Citation2007). As a result, tourism workers have limited collective bargaining power for a better ‘human resource contract’ (Baum, Citation2007). However, the importance of service work in the South African, and other economies owing to the size and growth of services in modern economies, necessitates greater attention to labour market issues in tourism and other service sectors (Zampoukos & Ioannides, Citation2011; Baum, Citation2015). Baum (Citation2015:206) argues:

More people working in tourism, in whatever capacity, raises the significance of the sector in political, economic and social terms at a local and national level. As a consequence, it places key issues relating to tourism employment, such as working conditions and remuneration levels, in greater public focus.

3. Methods

Before continuing, it should be noted that while this paper uses tourism and hospitality (T&H) as a term, hospitality is regarded as a sub-sector of the tourism industry or sector. The boundaries of the travel and tourism industry, hereafter the tourism sector, as per the Tourism Satellite Account (TSA) comprise: transport, accommodation, catering, recreation, entertainment and other travel services. Accordingly, as employed in this paper, the tourism sector encompasses hospitality unless in cases were a distinction is drawn in the data and discussions.

To set the scene, data on tourism employment from the TSA statistical releases by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) are offered. Note that the TSA draws employment data from Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS). Tourism employment figures and demographic data on race, gender and age are provided. This is followed in the second instance by data on educational attainment and skills from the Training Needs Analysis (TNA) survey which formed part of a study, conducted in 2016–17 for the National Department of Tourism, to inform the Tourism Sector Human Resource Development (THRD) strategy for South Africa, 2017–27. The TNA was an online firm-level survey targeting individual employees in a cross-section of tourism enterprises using the Organising Framework of Occupations (OFO). The OFO is a classification system based on the International Labour Organisation’s International Standard Classification of Occupations. The OFO offers a common basis for occupational categories across institutions and industries (DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training), Citation2012). For this research, databases of tourism establishments were obtained from the number of organisations and departments.Footnote2 A single database was then compiled and cleaned. A non-random quota-based sampling process was adopted with multi-layered stratification by firm size and tourism sub-sector. The realised sample was 136 firms with a total of 2,058 employees (out of a targeted 10 918) completing the survey. This sample met the stratification criteria in terms of firm size and representation of firms in the tourism sector. In the third instance, educational data on T&H at the secondary school, Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) college and university levels, obtained from the Department of Basic Education (DBE) and Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), are delineated.

This paper also incorporates findings from qualitative engagements which formed part of the THRD strategy study. These consisted of tourism stakeholder roundtables held in each of South Africa’s provinces (N = 9) and with key role-player groups (N = 3), along with 19 key informant interviews.Footnote3 The engagements were recorded and reports were produced for each of the roundtables along with transcripts for the key informant interviews. The analysis was thematic, using keywords and frequency. In other words, sentiments, impressions and perceptions shared by several groups or individuals and came to the fore repeatedly in different engagements are offered in this paper.

4. Youth employment and skills in tourism: the South African evidence

4.1. Tourism employment with reference to gender and age

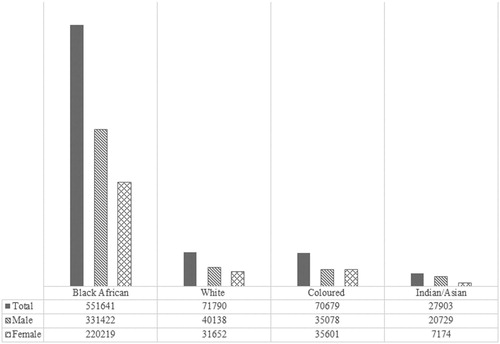

Employment in tourism is on an upward trajectory overall. According to TSA figures, total direct tourism employment stood at 722 013 in 2017 (5% of total employment) in comparison with 623 299 in 2011. Of tourism employees in 2017, more than three-quarters were Black Africans (76%), followed by Whites (10%), Coloureds (10%) and Indians/Asians (4%) – see for an employment figure table by raceFootnote4 and gender. Overall, females made up 41% of the tourism workforce in 2017.

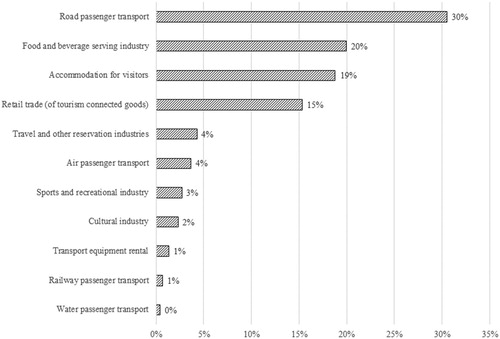

QLFS data reveal that up to 68% of the tourism workforce was aged 40 years or younger in 2015 (see Booyens et al., Citation2020). The picture concerning gender and age changes somewhat when a closer look is taken at the hospitality sub-sector. provides a breakdown of tourism employment by sub-sector as per the TSA definitions. Within the tourism sector, hospitality (accommodation combined with food and beverages) employs the most persons – 39% the total tourism workforce in 2017. The vast majority of hospitality workers was Black (78.2% in 2017), female (61.6% in 2017) and aged 40 years or younger (78.4% in 2015; see Booyens et al., Citation2020). Although not directly comparable to the QLFS figures, the TNA also alludes to an overwhelmingly young hospitality workforce with 64% employees aged 35 years or younger, predominantly in elementary jobs.

4.2. Educational attainment and career progression

According to the TNA, the vast majority of tourism employees had a post-school diploma or below with only 16% of employees holding a Bachelor’s degree or higher (). Furthermore, 79% of tourism employees did not have tourism-specific qualifications (). This was most pronounced in elementary positions – 97% did not have a tourism-specific qualification.

Table 1. Educational attainment of tourism employees, 2016.

Table 2. Tourism-specific qualifications of tourism employees by occupational group, 2016.

The qualitative findings confirm that tourism is widely regarded as a sector with low entry barriers (as evident in the data presented in and ). Private sector respondents underscored that experience and a willingness to learn often counts more than formal qualifications. Various tourism industry respondents argued that is important to ‘start at the bottom’, ‘work yourself up’ and gain experience by doing ‘less glamorous’ tasks. Several respondents who had experience working with graduates alleged that they typically do not want to ‘serve’, lack motivation to work in the sector and are not willing to do menial tasks because they have formal qualifications and expect better positions. Conversely, while there likely are broader economic or structural factors as to why T&H graduates experience difficulty in finding jobs, the qualitative findings of this study does attribute this to a lack of appropriate skills and also experience as articulated in the next main section.

The TNA further reveals that there are limited opportunities for persons who are employed in tourism to upskill and progress in their careers. The vast majority of employees (78%) did not continue their education or training after entering the workforce (). Managers and professionals were the occupational groups most likely to continue their education (32% and 34% continued their education respectively), while only 7% of employees in elementary positions did so. At the same time, employees in elementary, craft or sales occupations remained in their positions much longer (12.1 years in the same position for workers in elementary jobs) than those in more senior positions (i.e. 5.8 years in the same position for managers; ).

Table 3. Continued education by tourism sector employees, 2016.

Table 4. Tourism sector employee experience by occupation, 2016.

5. T&H education and skills training in South Africa

5.1. T&H offerings at the school, TVET and university levels

In South Africa, T&H education and skills training are well established at both the secondary and tertiary education levels. Tourism and hospitality are both secondary school subjects. Tourism was introduced as a high school subject in 2006. Hospitality incorporates elements of the old ‘Home Economics’ subject area. There were 2,901 schools offering tourism (with 144 643 learners), versus 339 schools offering hospitality (with 8,895 learners) in 2015 (). Tourism has grown as a subject area between 2011 and 2015, and it is estimated that 22% of all Grade 12 learners had tourism as a subject 2015 (DBE interview). At the same time schools offering, and learners taking, hospitality as a subject has decreased slightly during the same period. The aggregate pass rates for tourism and hospitality are extraordinarily high, 96% for tourism and 98% for hospitality between 2011 and 2015 (DBE data).

Table 5. T&H at school level, 2011–15.

T&H courses are also offered at TVET colleges which evolved from the old technical colleges, also formerly called Further Education and Training colleges.Footnote5 In recent years, there has been a marked increase in students who registered, wrote and passed T&H courses at TVET colleges. Between 2011 and 2014, the number of students writing tourism and hospitality examinations increased with 25% and 28%, respectively (). The number of tourism graduates was slightly higher than for hospitality. A total of 1,197 students completed tourism courses in 2014 of which 70% female and 1,005 completed hospitality-related courses of which 79% were female. It is evident that less than half of students who registered, in tourism and hospitality alike, completed their studies.

Table 6. Student figures for tourism and hospitality at TVET colleges*, by gender, 2014.

This study identified 17 Universities and Universities of Technology offering T&H courses at both the under- and post-graduate levels. Again, the number of travel and tourism graduates was much higher than for hospitality. In 2014, 55% of travel and tourism and 73% of hospitality graduates were female ()

Table 7. Student figures for travel and hospitality at tertiary level.

This study also identified 78 private institutions and colleges offering T&H related courses.Footnote6 While not discussed in this paper, tourism associations, government departments (local, provincial and national) and CATHSSETA are also involved in T&H education and training. It should be noted that there is considerable overlap or duplication with regards to the offerings of the education and training providers mentioned above.

It is evident from the data presented above that enrolments in T&H at the school and TVET levels have increased markedly in recent years. Tourism as a subject area has shown greater increases in comparison with hospitality. It should be noted that tourism is less costly to deliver than hospitality which requires fully equipped kitchens at training institutions. However, a key finding of this study was that there is a mismatch between the outcomes of education and skills training in tourism and the requirements of the industry. This relates to the quality of T&H education and training offerings which was a key discussion point at many qualitative engagements as unpacked further below.

5.2. The quality of T&H education and training

Respondents widely regarded T&H as ‘easy’ options particularly at the high (secondary) school and TVET levels. While it is recognised that schools need to offer a range of subjects which include vocational choices, certain respondents felt that too many students opt for these ‘easy’ subjects without any real interest in T&H to avoid ‘harder’ subjects like mathematics and science. This was confirmed by the increasing number of students especially taking tourism as a matric subject and at TVET level and by the very high pass rates as presented above. A further concern at school level was that there are not enough teachers who are trained as tourism subject-matter experts. According to the DBE, there are about 4,000 tourism teachers nationally, however only an estimated 4% reportedly have tourism related qualifications. Moreover, it was alleged that many teachers are not in touch with what is happening in the industry and some have never been tourists themselves. The capabilities of TVET lecturers were also raised as a concern. It was stressed by respondents familiar with TVET colleges that these environments do not attract the ‘best’ lecturers. Many lecturers reportedly are former artisans with limited academic credentials and others were said to have limited tourism industry experience and understanding. Moreover, many did not have formal training as educators or lecturers. An educational specialist pointed out that there remains widespread negative perceptions about TVET colleges, i.e. that they offer ‘inferior’ qualifications. TVET colleges are pressured in terms of resources because they have in recent years experienced an increased influx of students who cannot get into universities and who are attracted by promises of ‘free’ education through National Student Financial Aid Scheme bursaries and monthly allowances.

Several respondents felt that the course content at school, TVET colleges and also some universities are not aligned to industry needs. This was in part attributed to limited or a complete lack of engagement by some colleges and higher education institutions with tourism sector stakeholders. It further was stressed that the content of certain T&H courses are out-dated and revisions are long overdue. There was consensus among several respondents that the vocational skills training in T&H needs to be improved to enhance the employability of graduates. In particular, soft skills training and specific skills for tourism sub-sectors are needed. There is also a need to improve Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) placements which emerged to be a serious challenge for TVET colleges. It, however, was felt that work experience placements are more streamlined and successful at some universities. At TVET colleges, only an estimated 41% of students had a WIL placement as part of their course. A complaint from TVET lecturers was that the curricula do not allow enough time for WIL and the placements accordingly are very short. In addition, staff said that they struggle to place students successfully because they do not have industry contacts and enough time to facilitate this due to various other duties. Respondents, from TVET colleges as well as the educational specialists interviewed, indicated that TVET colleges experience several challenges because training budgets are low and they are typically under-resourced and -staffed. Last but not least, learning pathways were perceived to be lacking. Both matriculants and TVET graduates in the T&H fields reportedly struggle to gain acceptance to universities to further their studies.

6. Discussion and conclusions

Females and youth are well represented in the tourism workforce, especially in hospitality. However, this paper reveals that the youth find themselves in precarious employment especially in hospitality where the bulk of employees are young and predominantly employed in elementary positions. The TNA suggests that those in elementary jobs have a bleak future, they typically: are those with the lowest qualifications, do not continue their education and training after being employed, and stay in the same job for years. Positions held in T&H relative to race need to be scrutinised further since observers stress that in South Africa Black females with low levels of education characteristically occupy low level T&H jobs (Kaplan, Citation2004; Maumbe & Van Wyk, Citation2011). This said, this findings outlined above corresponds with the international literature which point to limited opportunities for youth in T&H (Zampoukos & Ioannides, Citation2011; Baum, Citation2015; Baum et al., Citation2016; Mooney, Citation2016). Furthermore, the findings regarding unrealistic expectations by youth of what the workplace can offer and their perceived lack of passion or motivation also align with the literature (Yu, Citation2013; Baum, Citation2015; Baum et al., Citation2016). However, Baum et al. (Citation2016) aver that generational differences are evident when it comes to work values, job satisfaction and engagement, work-life balance and the intention to leave.

While the prospects for youth in tourism employment are questionable, the numbers of school levers, along with TVET and university graduates, specialising especially in tourism are increasing. Conversely, the TNA data indicate that vast majority of tourism employees do not have a Bachelor’s degree and the most by far do not hold tourism-specific qualifications. At the same time, the qualitative findings underscore a widespread perception that formal qualifications are not needed per se for persons to be employed in tourism. Furthermore, there are said mismatches between skills gained from formal T&H qualifications and industry needs. These issues are discussed further below.

The impression that T&H courses are ‘easy’ options is not unique to South Africa, Williamson (Citation2017) also indicates that hospitality often is considered a ‘dummy’ subject at school. Nonetheless, this has significant implications for education in South Africa. The increase in learners taking T&H subjects particularly at school level needs to be contextualised in view of decreasing numbers of learners taking and passing mathematics and science at matric level because they seemingly do not ‘cope’ with these subjects (Yu, Citation2013). The qualitative findings suggest that learners take T&H subjects for an easy matric pass without the interest or ambition to continue with a T&H career after school. Those who do want to pursue T&H reportedly often struggle to access universities because of their overall poor matric results, that is not achieving a bachelors or diploma pass respectively for University or University of Technology admission. Many school leavers accordingly turn to TVET colleges where the T&H throughput rates are low – less than half of those who enrol complete their courses. Those who do complete their courses often cannot gain access to the labour market or universities to further their education. The concern with university access is two-fold, one is centred on articulation and the another on the quality of education especially at the basic level. Articulation is a common issue in education in South Africa, particularly in relation to TVET graduates (Mashongoane, Citation2018; Rogan, Citation2018). While the DHET indicates that learning pathways in T&H from TVET colleges to Universities in have been gazetted, graduates report challenges according to TVET lecturers that is: certain universities do not to recognise their qualifications. Therefore, the issue of learning pathways in T&H requires attention at institutions of higher learning.

Complaints that TVET and university courses in South Africa do not meet industry needs are also by no means unique to T&H (Mashongoane, Citation2018; Rogan, Citation2018) or to T&H in South Africa (Baum, Citation2007; Marchante et al., Citation2007). This study identifies soft skills outcomes in T&H education and training programmes as a key area for improvement. While Yu (Citation2013) stresses that youth typically lack soft skills, the enhancement of soft skills are particularly important for T&H because the workplace places value on customer care. In correspondence, Baum (Citation2015) urges for skills development in tourism beyond a focus on technical skills. This research also calls for skills training in T&H, which is sector-specific (addressing the needs of tourism sub-sectors) and not necessarily formal (see Baum, Citation2007) to enhance employability of tourism graduates (also see Booyens et al., Citation2020). A further challenge is the lack of graduates’ workplace experience. While this is also not unique to T&H (Mashongoane, Citation2018; Wildschut & Kruss, Citation2018), work experience is highly valued by employers even more so than qualifications in T&H as confirmed by this research. This presents a conundrum vis-à-vis education and training, and labour market absorption in T&H fields.

In view of the above, the value to T&H education and training especially at the school and TVET levels needs to be questioned. A key implication is that the push of learners and students through ‘easy’ and ‘free’ routes at school and TVET levels should be rethought. Arguably, this should not be encouraged at the expense of more viable vocational or Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) options which requires more students to complete matric with mathematics and science. Even though tourism is a growth sector, there is limited evidence that T&H graduates are in fact being absorbed into tourism sector employment in South Africa. There is also limited, if any, data on how long they stay if they are employed. There is a clear need for tracer studies of T&H graduates to illuminate these issues in the South African context. International studies suggest that staff turnover is often very high especially in hospitality (Zampoukos & Ioannides, Citation2011; Baum et al., Citation2016). On the other side of the coin are women and youth who arguably fall into a low-skill, low-wage trap. A greater focus needs to be placed on skills training to stimulate vertical movement in the T&H workforce through upskilling, accompanied by mentorship programmes and pathways to the labour market for youth (see Wildschut & Kruss, Citation2018). Moreover, the private sector needs to partner with the public sector to create better opportunities for youth in tourism. Shakeela et al. (Citation2012:115) cite an Irish strategy which supports ‘the development of professional career paths for key occupations in tourism, delivery of flexible and relative programmes leading to internationally recognised qualifications, streamlining tourism education and training, positioning the industry as a highly attractive career choice’. Similar initiatives in South Africa with an emphasis on youth, will afford tourism workers opportunities for human development, decent employment and career advancement. At the same time, students and stakeholders also need to be realistic about what the tourism sector can offer in terms of employment.

In conclusion, it is acknowledged that many of the issues identified in this paper are not unique to the tourism sector, yet there are important issues and caveats to consider to in relation to drawing youth into and advancing them in tourism which is touted as a growth sector promising jobs in a country where unemployment, especially among the youth, is rife.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this paper is based was done under the auspices of the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) on commission for the National Department of Tourism in South Africa. I acknowledge colleagues in the HSRC research team of which I was part, particularly Ms. Shirin Motala and Mr. Stewart Ngandu who led the project. I wish to thank Dr. Glenda Kruss at the HSRC for her useful comments on an earlier version of this paper and also the reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 President Ramaphosa emphasised the importance and potential of tourism in both his 2018 and 2019 SONAs.

2 The National Department of Tourism; Culture, Arts, Tourism, Hospitality and Sport Sector Education and Training Authority (CATHSSETA); Southern Africa Tourism Services Association; Gauteng Provincial Government; Eastern Cape Provincial Government; Western Cape Provincial Government; and the South African National Parks Board.

3 With tourism industry associations (N = 6); government departments involved in tourism education, skills planning, implementation and/or regulation (N = 7), and private sector initiatives and NGOs involved in promoting transformation and skills training in the sector (N = 6)

4 The race categories used are those delineated in the TSA statistical releases. Race is not discussed in this paper at length due to space limitations and since the emphasis is rather on the age of workers.

5 There are about 50 TVET colleges with 256 sites of delivery and 12 new colleges, many of which offer tourism, hospitality and consumer studies.

6 Note that we did not have access to data on the student figures and performance data of private institutions

References

- Altman, M, 2006. Identifying employment-creating sectors in South Africa: The role of services industries. Development Southern Africa 23(5), 627–47.

- Baum, T, 2007. Human resources in tourism: Still waiting for change. Tourism Management 28(6), 1383–99.

- Baum, T, 2015. Human resources in tourism: Still waiting for change? – A 2015 reprise. Tourism Management 50, 204–12.

- Baum, T, Cheung, C, Kong, H, Kralj, A, Mooney, S, Thanh, HNT, Ramachandran, S, Dropulić Ružić, M & Siow, ML, 2016. Sustainability and the tourism and hospitality workforce: A thematic analysis. Sustainability 8(8), 809–29.

- Becker, GS, 2009. Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Bhorat, H, Cassim, A & Tseng, D, 2016. Higher education, employment and economic growth: Exploring the interactions. Development Southern Africa 33(3), 312–27.

- Bhorat, H, Steenkamp, F, Rooney, C, Kachingwe, N & Lees, A, 2018. Understanding and characterizing the services sector in South Africa: An overview. DPRU Working Paper 201803. Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Black, A & Gerwel, H, 2014. Shifting the growth path to achieve employment intensive growth in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 31(2), 241–56.

- Booyens, I, Motala, SY & Ngandu, S, 2020. Tourism innovation and sustainability: Implications for skills development in South Africa. Forthcoming. In T Baum & A Ndiuini (Eds.), Sustainable HRM for tourism in Africa. Springer, Cham.

- Cichello, P, Leibbrandt, M & Woolard, I, 2014. Winners and losers: South African labour-market dynamics between 2008 and 2010. Development Southern Africa 31(1), 65–84.

- De Beer, A, Rogerson, CM & Rogerson, JM, 2014. Decent work in the South African tourism industry: Evidence from tourist guides. Urban Forum 25, 89–103.

- DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training), 2012. Guidelines: Organising framework for occupations. DHET, Pretoria.

- Fourie, J & Santana-Gallego, M, 2013. The determinants of African tourism. Development Southern Africa 30(3), 347–66.

- Grice, J, 2019. Why are so many young people NEETs? South African Journal of Science 115(7/8), 7.

- Kaplan, L, 2004. Skills development in tourism: South Africa's tourism-led development strategy. GeoJournal 60(3), 217–27.

- Makumbirofa, S & Saayman, A, 2018. Forecasting demand for qualified labour in the South African hotel industry. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences 11(1), 1–11.

- Marchante, AJ, Ortega, B & Pagán, R, 2007. An analysis of educational mismatch and labor mobility in the hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 31(3), 299–320.

- Mashongoane, T, 2018. Continued learning and employment: Destinations of TVET engineering graduates in the North West Province. In M Rogan (Ed.), Post-school education and the labour market in South Africa, 187–96. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Maumbe, KC & Van Wyk, LJ, 2011. Addressing the skills shortage problem of the South African tourism and hospitality industry: An evaluation of the effectiveness of the 2007/2008 SA Host training program in the Western Cape Province. Urban Forum 22(4), 363–77.

- Mooney, SK, 2016. Wasted youth in the hospitality industry: Older workers’ perceptions and misperceptions about younger workers. Hospitality & Society 6(1), 9–30.

- Rogan, M, 2018. The post-school education and training landscape in South Africa: ‘Massification’ amidst inequality. In M Rogan (Ed.), Post-school education and the labour market in South Africa, 1–16. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Rogerson, CM, 2007. Reviewing Africa in the global tourism economy. Development Southern Africa 24(3), 361–79.

- Rogerson, CM, 2015. Tourism and regional development: The case of South Africa's distressed areas. Development Southern Africa 32(3), 277–91.

- Rogerson, CM, 2018. Unpacking the changing economic geography of Gauteng’s tertiary sector. In K Cheruiyot (Ed.), The changing space economy of city-regions, 157–84. Springer, Cham.

- Rogerson, CM, 2020. Sustainable tourism research in South Africa: In search of a place for work and the workplace. Forthcoming. In T Baum & A Ndiuini (Eds.), Sustainable HRM for tourism in Africa. Springer, Cham.

- Saarinen, J & Rogerson, CM, 2014. Tourism and the millennium development goals: perspectives beyond 2015. Tourism Geographies 16(1), 23–30.

- Shakeela, A, Ruhanen, L & Breakey, N, 2012. Human resource policies: Striving for sustainable tourism outcomes in the Maldives. Tourism Recreation Research, 37(2), 113–22.

- Standing, G, 2010. Work after globalization: Building occupational citizenship. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

- Standing, G, 2011. The Precariat: The new dangerous class. Bloomsbury Academic, London.

- Stats SA (Statistics South Africa), 2018. Tourism satellite account for South Africa, final 2015 and provisional 2016 and 2017. Stats SA, Pretoria.

- Stats SA, 2019. Quarterly labour force survey. Quarter 2, 2019. Stats SA, Pretoria.

- Tsangu, L, Spencer, JP & Silo, M, 2017. South African tourism graduates’ perceptions of decent work in the Western Cape tourism industry. African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences 23(Supplement 1), 54–65.

- Visagie, J & Turok, I, 2019. The contribution of services to trade and development in Southern Africa. UNU-WIDER, SA-TIED Working Paper #58.

- Wildschut, A & Kruss, G, 2018. Workplace-based learning programmes and the transition to the labour market. In M Rogan (Ed.), Post-school education and the labour market in South Africa, 197–222. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

- Williamson, D, 2017. Too close to servility? Why is hospitality in New Zealand still a ‘Cinderella’ industry? Hospitality & Society 7(2), 203–9.

- Yu, D, 2013. Youth unemployment in South Africa revisited. Development Southern Africa 30(4–5), 545–63.

- Zampoukos, K & Ioannides, D, 2011. The tourism labour conundrum: Agenda for new research in the geography of hospitality workers. Hospitality & Society 1(1), 25–45.