ABSTRACT

This article provides an overview of the main initiatives undertaken by the South African government through policy development to assist small, micro and medium enterprises (SMMEs). The article considers SMME awareness and perceptions of these initiatives. Furthermore, SMME perceptions of the challenges, barriers and reasons for failure are analysed. Data obtained from the 2016 SAICA SMME study was used as a basis for the analysis of the SMME perceptions to establish if an entity’s size has any bearing on these. The findings indicated the size of the SMME does statistically affect their challenges, barriers and perceptions of the government.

1. Introduction

Small, micro and medium enterprises (SMMEs) are universally acknowledged as important drivers of economic success, and are seen not only as job creators, but also as sales generators and as a source of tax and thus fiscal revenue (Bruwer et al., Citation2017a; OECD, Citation2017). The growth of the SMME sector has been emphasised over the past few years in numerous countries, such as the United States, United Kingdom, Brazil, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Malaysia and India (Maye, Citation2014; SBP, Citation2014; Makanyeza & Dzvuke, Citation2015; Gray & Jones, Citation2016; Boadi et al., Citation2017; Domeher et al., Citation2017). In South Africa, SMME growth is seen as one of the solutions to the country’s high unemployment rate as well as poor economic growth (National Planning Commission, Citation2012).

Notwithstanding this important role, this sector still faces many challenges in South Africa (SAICA, Citation2017) and due to high failure rates, SMMEs are not able to contribute to job creation and economic growth as envisaged. The South African government has not been oblivious to the needs and significance of this sector and has introduced a number of initiatives to support SMMEs (DTI, Citation2008; National Credit Regulator, Citation2011; National Planning Commission, Citation2012; Maye, Citation2014), however, these initiatives are often not tailored for businesses of different sizes and often only focus on the larger SMMEs (DSBD, Citation2019). Furthermore, Nieuwenhuizen (Citation2019) found that the regulatory environment hampers small business growth, thereby highlighting the need to investigate policy development in South Africa.

This article investigates whether the size of the SMME affects the challenges, barriers and reasons for failure experienced by small businesses. Furthermore, this article analyses whether the size of the SMME influences perceptions of the main initiatives undertaken by the government to assist the SMME sector in order to provide an understanding to the current situation in which SMMEs find themselves. A better understanding of these issues could guide government to develop improved size-specific policy initiatives for SMMEs and increase the awareness of its offerings.

This article is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a historic perspective of the government initiatives for SMMEs, Section 3 highlights the role and functioning of the Department of Small Business Development (DSBD) launched in 2014 and Section 4 explains the current challenges and barriers faced by SMMEs. Section 5 explains the methodology followed by the discussion of the findings in Section 6. The final section provides concluding remarks.

2. SMME initiatives introduced by the government

The government realised the importance of SMMEs shortly after 1994 and passed the National Small Business Act in 1996 and established the first National Small Business Council, which together set out the national strategy for the development and promotion of small business in South Africa (Maye, Citation2014). In 1998 the National Empowerment Fund (NEF) was formed to provide financial and non-financial support to black empowered businesses, thereby promoting investment in black-owned businesses (NEF, Citation2017).

In 2003, the government issued the Integrated Small-Enterprise-Development Strategy as the guideline for its support programmes and business development for the next ten years (DTI, Citation2003). This strategy identified micro enterprises, small business in high-growth sectors and black-owned and managed small and medium enterprises as SMMEs that require special support. The overall aim of this targeted support was to improve economic growth, create jobs and reduce poverty, however, according to Rogerson (Citation2004) and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) (Citation2008) SMMEs still did not seem to reach their full growth potential.

As part of continuous efforts to improve SMME support, the government implemented the National Small Business Amendment Act in 2004 (Maye, Citation2014). Through this Act, the Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA) was established as part of the DTI from a merger between entities incorporated to assist SMMEs with their growth and sustainability: Ntsika Enterprise Promotion Agency, National Manufacturing Advisory Centre and the Community Public Private Partnership Programme (National Credit Regulator, Citation2011). SEDA was, however, specifically mandated to assist SMMEs with non-financial support in terms of business strategy, design and implementation of small business development and also with the integration of government-funded small business support agencies in order to achieve their mission of development, support and promotion of SMMEs in South Africa (SEDA, Citation2017).

Subsequently, the DTI launched a second National Small Business Advisory Council in 2006 as required by the National Small Business Act 26 of 2003 with the aim to represent and promote the interests of small business in South Africa (National Credit Regulator, Citation2011). Other agencies established between 2006 and 2008 tasked to assist SMME owners included, among others, the Technology Innovation Agency, the National Youth Development Agency and the Micro-Agricultural Financial Institute of South Africa (National Credit Regulator, Citation2011).

In an effort to assist SMMEs with financing, the government, in 2012, launched the Small Enterprise Finance Agency (SEFA) as part of the DTI, which was formed by amalgamating entities tasked to assist SMMEs with their financing needs which included Khula Enterprise Finance Limited, the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) and the South African Micro-finance Apex Fund (National Credit Regulator, Citation2011; SEFA, Citation2017).

Finally, the DSBD – also known as the Ministry of Small Business Development – was established in 2014 to lead an integrated approach for the promotion and development of SMMEs and co-operatives by consolidating various public agencies including SEDA, Co-operatives Development Agency and Co-operatives Tribunal, and various state-owned entities (Office of the Premier, Citation2014).

3. Launch of the Department for Small Business Development – ‘the dream’

The DSBD is tasked with creating employment in the SMME environment and stimulating growth in the country. It is mandated to specifically improve the following for SMMEs: the legal and regulatory environment, access to different markets and to finance, the skill deficit in the country and access to information and involvement for growth from support institutions (Maye, Citation2014; SBP, Citation2014).

The four-key service offerings that are offered by the DSBD include the Black Business Supplier Development Programme (BBSDP) which offers grants to black-owned small businesses, the Co-operative Incentive Scheme (CIS) which is offered to registered primary co-operatives, the Share Economic Infrastructure Facility (SEIF) which offers grants to businesses that provide infrastructure to growing business environments and the National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy (NIBUS) which offers grants to entrepreneurs of certain designated groups in the informal economy. In addition, the DSBD also reported on assistance provided to small businesses through the Informal and Micro Enterprise Development Program (IMEDP) which is offered to developing informal and micro businesses owned by historically disadvantaged individuals and the Enterprise incubation programme (EIP) which is offered to assist with the establishment of new or existing incubators (DSBD, Citation2017a). A brief summary of these key service offerings is listed in .

Table 1. Department of Small Business Development key service offerings.

It is encouraging to see the broad, yet critical, focus areas of these key service offerings, however, there are some uncertainties. The first uncertainty relates to the number of service offerings available to small business owners. Additional to the key service offerings provided by the department, the DSBD also provides support to small businesses in other forms through sub-programmes, for example, the Informal Trader Upliftment Programme (ITUP) which provides training to informal traders. A complete list of these programmes is not available from the public available electronic sources and therefore, qualifying small business owners might find it difficult to identify of all the available programmes that might be of assistance (DSBD, Citation2019).

Another uncertainty is the requirement of being a business registered for Value-added tax (VAT) – this requirement is only mentioned in the BBDSP offering but the other offerings are silent on this issue. Should VAT registration not be a requirement, this would certainly assist micro entities with their tax compliance burden (Smulders et al., Citation2012).

When considering the performance of the DSBD, its 2014/15 Annual Report revealed that the newly formed ministry had failed in fulfilling its mandate by missing every single one of its four performance targets set for the year (Democratic Alliance, Citation2015; Parliamentary Monitoring Group, Citation2015).

Despite this failure, a budget of R1.127 billion was allocated to the DSBD by the government for the 2015/2016 year, of which the DSBD spent R1.098 billion, resulting in a 2.6% underspending in expenditure as per the budget. However, in terms of the key performance indicators that the DSBD set out to achieve through the above-mentioned programmes, an overall performance of 41.9% was achieved during the 2015/2016 financial year. For that financial year, the Auditor General of South Africa (AGSA) issued the DSBD with an unqualified audit opinion but indicated approximately R1.8 million as irregular expenditure in terms of bidding requirements that were not met. All other material misstatements to the annual financial statements found were corrected (Parliamentary Monitoring Group, Citation2017). Apart from the unsatisfactory results mentioned above, there were some highlights for the 2015/2016 financial year and the DSBD reported that R1.08 billion was disbursed to 45 263 small businesses and co-operatives (South African Government, Citation2016).

In terms of the 2016/2017 financial year, the DSBD was allocated R1.3 billion of which 17% was allocated to administration and personnel costs. The other 83% was allocated to programmes of the DSBD (36%), SEDA (48%) and SEFA (16%) (South African Government, Citation2016). The department also spent 90.8% of its total budget of R1.3 billion which translates to an underspending of R122 million for which the department provided reasons and strategies to be implemented for correction. Although some highlights were reported in the DSBD’s annual report for the 2016/2017 financial year, there were also areas of underperformance. Reasons for the underperformance included administration problems due to system errors, lack of leadership, project ownership, under-capacity, poor planning and execution, shortage of enough staff members or consultants and lack of budget allocations (DSBD, Citation2017a)

For the 2017/2018 financial year, the DSBD was awarded R1.4 billion. The DSBD spent 98.9% of its budget and met 62.9% of their targets (DSBD, Citation2018; Parliamentary monitoring group, Citation2018). According to the annual report for the 2017/2018 financial year, the DSBD received an unqualified audit report without any irregular expenditure, however, the AGSA reported on material findings on non-compliance which related to funds that were not utilised for the purposes as intended (DSBD, Citation2018; Parliamentary monitoring group, Citation2018).

The AGSA further raised concerns regarding the lack of oversight of performance and monitoring of some of the incentive programmes as well as the absence of reliable performance reports (DSBD, Citation2018). The lack of oversight is quite worrisome as continuous monitoring and evaluation remains a focus area in the DSBD’s strategic plan for 2015–2019 (DSBD, Citation2017b) and still does not seem to be enforced by the department which might indicate that the reasons for underperformance identified in the previous financial year are still prevalent.

4. SMME sector challenges and barriers – ‘the reality’

In government’s 10-year review of its SMME policies up to 2004, it identified that its grant programmes, in collaboration with private and public service providers, had diversified significantly and offered more support options to more small enterprises. According to Rogerson’s (Citation2004) review of the impact of government’s programmes from 1994 to 2003, SMMEs did not contribute meaningfully to job creation due to a lack of growth. In addition, he emphasised that most programmes ignored the micro and informal enterprises. However, government expected these efforts to realise in intangible benefits during the next 10 years (DTI, Citation2004).

Notwithstanding the efforts made and new initiatives implemented by the government, Mr Rob Davies, the previous Minister of Trade and Industry, indicated that about 70% of SMMEs in South Africa fail during their first year, which is among the highest failure rates across the world (Maye, Citation2014; SME South Africa, Citation2016). In contrast to this, according to studies conducted by Finscope (Citation2010) and Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) (Citation2016), South Africans seem to feel positive towards the entrepreneurial business opportunities in the country and are optimistic that they have the necessary skills, knowledge and experiences to run their own businesses. The GEM (Citation2016) report does, however, also note that despite the perceptions of optimism expressed by the respondents, South Africa is one of the countries that experiences some of the weakest entrepreneurial conditions among several countries (GEM, Citation2016).

When considering the specific challenges and barriers experienced by SMMEs, the DTI (Citation1995) initially found that the legal and regulatory environment confronting SMMEs, access to markets, finance and business premises (at affordable rentals), acquisition of skills and managerial expertise, access to appropriate technology, quality of the business infrastructure in poverty areas and in some cases, the tax burden were problematic for SMMEs.

Subsequent studies (Brink & Cant, Citation2003; Ferreira et al., Citation2010; Herrington et al., Citation2017) have found that despite the targeted interventions by the government, the challenges experienced by SMMEs are many and SMMEs still have a high failure rate with Rogerson (Citation2008) stating that the two biggest contributors to business failure are managements’ lack of skills and training. Cant & Wiid (Citation2013) found macro-economic factors (inflation, interest rates, regulation, unemployment and crime), geographical location, price challenges and lack of product uptake as major challenges faced by SMMEs. In a more recent study, Shibia & Barako (Citation2017) identified factors such as SMMEs perceptions towards the legal system, access to finance, access to utilities and the prevalence of crime as factors that influence SMME growth.

It has been postulated that the impact of these challenges differs between SMMEs based on their size, industry, geographic location and the gender of the entrepreneur (DTI, Citation1995). More specifically, micro entities tended to be owner managed leading to a lack of management skills, support services and avoidance of business growth (Gherhes et al., Citation2016).

It is evident that there is a gap between the realities of high SMME failure rates and the positive attitudes of SMME owners, specific programmes and interventions implemented by the government to assist this sector. Taking these interventions, challenges and barriers into account, this paper will investigate SMMEs’ current challenges and barriers to growth to see if these differ statistically between SMMEs based on their size. This article will also deliberate SMMEs awareness of and perceptions towards Government’s aims, through the DSBD, to assist in easing SMME challenges and barriers.

5. Methodology and research hypotheses

In order to gain further insight into this important sector of the economy, the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA) commissioned a study in 2016 on the practices, attitudes and characteristics of SMMEs in South Africa. The study was conducted digitally and respondents (1051) were invited to participate by email through business media and SAICA affiliated small and medium practices (SAICA, Citation2017).

After obtaining the necessary approval and ethical clearance from the University of South Africa’s Ethics Committee, the data obtained from the 2016 SAICA SMME study (SAICA, Citation2017) was used as a basis to analyse, in more detail, the challenges and barriers faced by SMMEs relative to their size. Their perceptions of the DSBD’s assistance and effectiveness were also solicited and analysed further.

For the purposes of this article, turnover was used to differentiate the businesses, as according to Loeprick (Citation2009) turnover is the simplest and most common way to segment businesses and taxpayers. Lignier (Citation2011) and Coolidge (Citation2011) both express a similar view, suggesting that turnover is a better indicator of business size than other criteria, as many provisions in the various tax Acts refer to turnover rather than number of employees.

Respondents were required to provide their business’ level of turnover and the respondents were grouped into four turnover bands to ensure sufficient representation in each group (see ).

Table 2. Grouping of business classes based on turnover.

Based on the preceding sections the following research hypotheses were developed and form the basis for this article:

H1: Differences exist in the perceptions of the challenges faced by SMMEs of different sizes

H2: Differences exist in the perceptions of the barriers faced by SMMEs of different sizes

H3: Differences exist in the perceptions of the reasons for failure of SMMEs of different sizes

H4: Differences exist in the perceptions regarding the DSBD by SMMEs of different sizes

After classifying the businesses into the different turnover bands, a one-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA) was used to determine if statistical significant differences exist between the views expressed by the different sizes of the business as stipulated in the various research hypotheses. The ANOVA is an omnibus test and does not provide information on which specific groups are statistically significant from the others. The Scheffe post-hoc test was thus performed to determine between which business sizes the statistical significant differences exist. As the number of responses for two of the turnover groups was particularly small when asked about the DSBD, a Kruskal–Wallis test was subsequently run on these responses to mitigate for the assumptions of the ANOVA not being met. Statistical significant differences are based on a 5% level indicated by a p-value of below 0.05 (Statistic Solutions, Citation2017).

6. Findings

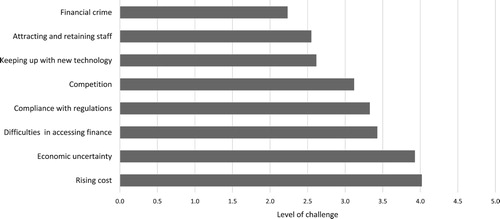

The SAICA (Citation2017) study requested respondents to identify the challenges that SMMEs experience in general. Rising costs and economic uncertainty/volatility were the biggest challenges facing SMMEs. The other challenges that SMMEs are faced with is set out in .

Figure 1. Challenges faced by SMMEs. Source: Adapted from SAICA (Citation2017).

Respondents were also required to identify the barriers that they experience when starting a new business of which the top two barriers were the difficulty in accessing finance and the level of red tape (SAICA, Citation2017). shows the other barriers that SMMEs experience.

Figure 2. Barriers experienced by SMMEs when starting a new business. Source: Adapted from SAICA (Citation2017).

These findings are similar to the challenges identified in the preceding section of this article. Therefore, despite all the efforts and initiatives of the government to support SMMEs, it appears that small business owners still find the small business environment difficult and risky, thus illustrating the importance of understanding the SMME sector better.

The SMME sector is by no means homogeneous (Loader & Norton, Citation2015) and this is specifically true in South Africa (Boamah-Abu & Kyobe, Citation2015; Maduku et al., Citation2016). As mentioned previously, one way of differentiating this sector is based on its size (Fang et al., Citation2016). It is, therefore, critical that the views of the different sized enterprises – micro, very small, small, and medium – be analysed in order to determine if their views on the challenges, burdens and perceptions of the DSBD are any different. This could assist in differentiating reforms for each size of business to alleviate their challenges and burdens.

6.1. Challenges

To determine whether the size of the business influences the challenges faced by SMMEs, an ANOVA was performed with regard to the different turnover bands (see Appendix 1). It was established that the following challenges were statistically significant between the different turnover groups at a 5% level – competition (F(3, 846) = 5.044, p = 0.002), difficulties accessing finance (F(3, 846) = 10.258, p = 0.000), compliance with regulations (F(3, 846) = 7.364, p = 0.000) and attracting and retaining staff (F(3, 846) = 5.525, p = 0.001). The Scheffe post-hoc test revealed that in respect of competition and compliance with regulations there is a significant difference in views on this matter between micro and small businesses.

With regard to the views on competition, the very small businesses regard competition as moderate to high, whereas small businesses regard competition as a low to moderate challenge. Interestingly, this indicates that the smaller the business, the higher the challenge of competition. This is opposite to the compliance with regulations, where the very small businesses regard this as a low to moderate challenge, but small businesses regard this as a moderate to high challenge. Competition is thus more of a challenge amongst the micro businesses whereas the compliance with regulations tends to be more of a challenge for the small businesses, who presumably are more formalised and have more administrative burdens and regulations to comply with.

In respect of difficulties accessing finance, the views of micro businesses differ significantly with all three other business classes. Overall, accessing finance is more of a challenge the smaller the businesses is. The opposite is true for attracting and retaining staff – the smaller the business, the less challenging it is to attract and retain staff – most probably because no additional staff are needed in, for instance, micro businesses. The Scheffe post-hoc test revealed that the perceptions of attracting and retaining staff as a challenge is significantly different between micro businesses and small and medium businesses, while very small businesses differ significantly with the views of medium-sized businesses. It appears that the more sophisticated the business gets (based on size), the more skilled-employees the business needs. As there is shortage of skills in South Africa (Bruwer et al., Citation2017b), it is apparent why the small to medium businesses perceive attracting and retaining staff to be a challenge.

Based on the above, evidence exists in favour of the first research hypothesis (H1) of this article. The size of the business does have an effect on the views of the businesses in respect of the challenges faced by SMMEs on a daily basis.

6.2. Barriers

The results from the ANOVA indicate that obtaining finance is the biggest barrier to starting a new business, and this view is the same irrespective of the size of the business (see Appendix 2). This is clearly a barrier that is contradictory to the NDP and needs serious consideration by policy makers.

The views on the following barriers were found to be statistically significantly different between the turnover groups at a 5% level:

red tape from government and large private businesses (F = 5.461, p = 0.001),

compliance with laws and legislation (F = 5.247, p = 0.001),

engaging with the Department of Labour (F = 5.145, p = 0.002),

operational issues such as finding customers, sourcing suppliers and marketing business (F = 3.245, p = 0.021),

registering for VAT with SARS (F = 5.967, p = 0.001),

engaging with SARS (F = 6.046, p = 0.000),

engaging with CIPC (F = 4.710, p = 0.003),

submitting documents with the CIPC (F = 4.783, p = 0.003),

registering or changing details with the CIPC (F = 6.429, p = 0.000).

When analysing this per turnover band, the Scheffe post-hoc tests revealed that for all the above major barriers the statistically significant difference is between the micro businesses and the small business. Except for operational issues, the small businesses regard red tape from government and large private businesses, compliance with laws and legislation, engaging with the Department of Labour and engaging with SARS as being a major barrier to starting a small business whereas the micro business do not regard these issues as such major barriers. A possible explanation for these differences in views could be because the micro businesses do not readily deal with government, large private businesses, Department of Labour and/or SARS due to the nature and size of their business. For instance, a micro business is not required to register for VAT because its turnover falls below the compulsory registration threshold of R1 million, but it can register for the turnover tax which is a simplified system aimed at making it easier for micro business to meet their tax obligations (SARS, Citation2017a).

The above findings are opposite to the views on the operational issues faced by business when starting up – micro businesses tend to regard this to be a major barrier, more than the small businesses. The smaller businesses appear to be more geared to deal with the everyday operational issues of a business compared to micro businesses that are just starting up or that just do not have the expertise or capacity to deal with customers, suppliers and marketing their business.

Registering a business for VAT with SARS tends to be a bigger barrier in the views of medium business (more than R20 million turnover). These views could be based on the problems experienced by these larger business in trying to register either their different divisions/subsidiaries or just merely based on their own entity’s experiences. Reasons for this are not elaborated on in the survey, but it is clear that the VAT registration process is the same for all businesses (SARS, Citation2017b). However, the documentary evidence required to substantiate the claim and the time taken to register a business might be the cause for these differing views as the owners/representative taxpayers of these business have to physically go to SARS for an interview in order to register the business as a VAT vendor. Registering for VAT in some instances can take up to six months (FSPBusiness, Citation2017).

Registering or changing details with the CIPC is regarded as a bigger barrier the bigger the businesses gets. However, medium businesses appear to be able to better undertake these functions than their smaller counterparts (other than micro businesses). Reasons for this could be that micro businesses are either not aware of CIPC, ignore their obligations in this regard or are not required to deal with them at all (for instance if the person trades as a sole proprietor). In respect of very small and small businesses, it could be that they have not performed these functions before or do not have (or cannot afford) the assistance of an accountant or advisor to assist them with these matters.

The results, therefore, support the second research hypothesis (H2) of this article. It is evident that the size of the business does have an effect on the views of the businesses in respect of the barriers to starting a new business. More in-depth research should be conducted on exactly why this is the case.

6.3. Reasons why SMMEs fail

SMMEs largely fail because of cash-flow problems and an inability to manage administrative and business processes (SAICA, Citation2017). Particularly, debtors that pay them late or don’t pay at all are a major reason for SMMEs failures. Other reasons include the fact that their overhead levels are too big, they are unable to survive on the margins that are dictated by the markets, they don’t take advice early enough, they are unable to manage/mitigate their business risks, they cannot manage their labour issues and their competitors have increased (SAICA, Citation2017).

An ANOVA performed on the SAICA survey data revealed that the following reasons for SMME failure were significant between the different turnover groups at a 5% level (see Appendix 3):

their inability to manage their cash flows (F = 3.095, p = 0.026);

their competitors have increased (F = 6.587, p = 0.000); and

they lack the internal business processes (F = 3.830, p = 0.010).

When analysing these reasons per turnover band, it is evident that in respect of managing their cash flows there is a significant difference in the views on this matter between most business sizes. The Scheffe post-hoc test reveals that a significant difference exists between the views of the micro and medium businesses. It appears that the larger the business, the bigger the cash flow management process becomes, presumably because there is more cash and processes to manage.

There is a significant difference in views on the increase in competition between micro and small businesses. The latter businesses find that competition is not such a major reason for small business failure, whereas the former have seen an increase in the number of competitors in the market and do regard this as one of the reasons for small business failure.

The view on the lack of business processes to help the company function is that micro businesses tend to regard this a major reason for small business failure. The medium-sized businesses regard this as less of a reason for small business failure. Bigger businesses appear to be more in control of their business processes and hence their long-term sustainability is more secure than smaller businesses.

The results, therefore, provide evidence in favour of the third research hypothesis (H3) of this article. It is once again evident that the size of the business does impact the SMME behaviour, operations and success (or failure). Attention will now be given to the thoughts of the respondents concerning the DSBD and its role to assist SMMEs.

6.4. Department of Small Business Development

The respondents were asked whether they were aware of the DSBD and, if so, to then rank various statements about the DSBD as to whether they agree with them or not.

Despite 73.8% of the respondents not being aware of the DSBD, it was found that small businesses are more aware of the DSBD than other sized businesses. However, the Pearson’s Chi-Square test (X(3) = 1.492, p = 0.684) revealed that statistically there is no relationship between the size of the business and their awareness. There is therefore not sufficient evidence in favour of the fourth research hypothesis (H4) of this article. Thus SMMEs, irrespective of their size, are similarly aware/unware of the DSBD and size does not appear to be a factor in this matter.

The following statements (in relation to the DSBD – see ) were provided to the respondents for them to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement. They could rank them as follows: from 1 to 7 with 1 indicating they completely disagree to 7 indicating that they completely agree.

Table 3. Statements regarding the DSBD in questionnaire.

Overall, it is evident that most respondents did not overwhelmingly agree with these statements but were either neutral or in disagreement with them. The sufficiency of the DSBD’s budget is the one area that respondents indicated greater agreement.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test are set out in . The results indicate that there is a statistical significant difference, at the 5% level of significance with regard to Statement 3 (The DSBD has improved access to finance for SMMEs) (p = 0.018) and Statement 8 (The DSBD has reduced government generated red tape) (p = 0.048). Statement 6 (The DSBD has helped by creating tax incentives for SMMEs to grow) is statistically significant at a 10% level (p = 0.080). None of the other statements showed statistical significant differences between the differing turnover bands.

On further analysis, it is established that small businesses mostly differ in their responses from the other turnover groups (see Appendix 4). Businesses of this size tend to disagree more strongly that the DSBD has improved access to finance for SMMEs. Furthermore, they also tend to disagree more that the DSBD has helped create tax incentives for SMMEs to grow. Interestingly, medium businesses agree strongly, more than all those with a turnover below R20 million that the DSBD has helped create tax incentives. As most of the tax incentives are for businesses with a turnover of R20 million or less (for example the SBC regime), this indicates that those not receiving the incentives appear to know of and agree that they are being created for small businesses, but those that are meant to be the beneficiaries of these incentives do not have the same sentiments. It is therefore evident that those that are meant to be benefiting from the tax incentives are not entirely satisfied with them.

In respect of the reduction of government red tape by the DSBD, a similar result was found – small businesses disagree more with this statement than those from other turnover groups, but the distinction is not as pronounced between those above and below the R20 million turnover threshold. Reasons for this are not readily evident and more research would need to be conducted into this finding.

7. Conclusion

It was hypothesised in this article that differences exist in the perceptions of the challenges and barriers faced by SMMEs, as well as in respect of the reasons for SMME failure. It was also hypothesised that the different sized businesses also differ in their views of the DSBD that was established to specifically assist SMMEs.

Using various statistical techniques, it was established that differences do exist in the perceptions depending on the size of the business. More specifically, in respect of the competition faced by an SMME, micro businesses found this to be more of a challenge than the other sized businesses. Compliance with regulations tended to be more of a challenge for the small businesses. Overall, accessing finance is perceived to be more of a challenge the smaller the businesses is, however, the smaller the business, the less challenging it is to attract and retain staff.

When considering the barriers, the results indicated that obtaining finance is the biggest barrier to starting a new business, and this view is the same irrespective of the size of the business. Unlike micro businesses, small businesses regard red tape from government and large private businesses, compliance with laws and legislation, engaging with the Department of Labour and SARS as being major barriers to starting a small business whereas the micro business do not regard these issues as such major barriers. Registering a business for VAT with SARS tends to be a bigger barrier in the views of medium business compared to other sized businesses. The operational issues faced by a business when starting up tend to be a major barrier for micro businesses more than for small businesses. Registering or changing details with the CIPC is regarded as a bigger barrier the larger the turnover of the businesses gets.

An analysis of the SMME perceptions of the reasons for SMME failure indicated that micro and medium businesses differ in opinion with regard to the cash flow management processes presumably because there is more cash and processes to manage in a medium business than a micro business. A significant difference in views was also found concerning the increase in competition between micro and small businesses.

It was found that 73.8% of the respondents were unaware of the DSBD and size does not appear to be a factor in this matter. Small businesses mostly differ in their responses from the other turnover groups in respect of the improved access to finance, creating tax incentives and reducing government red tape. More specifically, it was established that SMMEs with a turnover of below R20 million tend to feel that the DSBD has not helped by creating tax incentives for small businesses to grow. It is exactly these businesses that are meant to be the recipients of the tax incentives. This discouraging finding indicates that this is an area that requires policy makers and revenue authorities’ immediate attention.

Thus, although the government has over the last twenty odd years endeavoured to assist the SMME sector, it is evident that a lot more work is needed. The incentives to assist this sector need to be stratified and more focused based, inter alia, on the size of the business. Micro and very small businesses need special attention to lower the unemployment rate and have a positive effect on the economy and the role of the DSBD in this regard needs to be more prominent.

The results of this article, therefore, support the hypotheses that the perceptions of SMMEs with regard to the challenges, barriers, reasons for SMME failure and the DSBD do differ based on their size. To stem the unemployment crisis in South Africa a differentiated approach to assist SMMEs to unblock the obstacles such as obtaining financing and to ease the complexity of doing business is needed. Ultimately the size of a business does matter and it is hoped that future government initiatives will take more cognisance of this fact when developing or improving SMME initiatives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Boadi, I, Dana, LP, Mertens, G & Mensah, L, 2017. SMEs’ financing and banks’ profitability: A ‘good date’ for banks in Ghana? Journal of African Business 18(2), 257–77. doi: 10.1080/15228916.2017.1285847

- Boamah-Abu, C & Kyobe, M, 2015. IT governance practices of SMEs in South Africa and the factors influencing their effectiveness. In Strategic information technology governance and organizational politics in modern business, 188–207. IGI Global, Pennsylvania.

- Brink, A & Cant, M, 2003. Problems experienced by small businesses in South Africa. Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference of Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand, 28 September–1 October, Ballarat.

- Bruwer, JP, Coetzee, P & Meiring, J, 2017a. The empirical relationship between the managerial conduct and internal control activities in South African small, medium and micro enterprises. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 20(1), 1–19. doi: 10.4102/sajems.v20i1.1569

- Bruwer, JP, Coetzee, P & Meiring, J, 2017b. Can internal control activities and managerial conduct influence business sustainability? A South African SMME perspective. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-11-2016-0188

- Cant, M & Wiid, J, 2013. Establishing the challenges affecting South African SMEs. International Business & Economics Research Journal 12(6), 707–16.

- Coolidge, J, 2011. Re: Comparative compliance costs project. [E-mail from:] Coolidge, J ([email protected]) [E-mail to:] Smulders, S.A. ([email protected]) 19 August 2011.

- Democratic Alliance, 2015. Small business ministry misses every one of its performance targets. https://www.da.org.za/2015/10/small-business-ministry-misses-every-one-of-its-performance-targets/ Accessed 27 August 2017.

- Domeher, D, Musah, G & Hassan, N, 2017. Inter-sectoral differences in the SME financing gap: Evidence from selected sectors in Ghana. Journal of African Business 18(2), 194–220. doi: 10.1080/15228916.2017.1265056

- DSBD (Department of Small Business Development), 2017a. Annual report 2016/17 vote no 31. http://www.dsbd.gov.za/?wpdmpro=annual-report-201617-vote-no-31 Accessed 14 January 2019.

- DSBD, 2017b. Department of Small Business Development strategic plan (revised 2017) for the fiscal years 2015–2019. http://www.dsbd.gov.za/?wpdmpro=dsbd-strategic-plan-2015-2019 Accessed 14 January 2019.

- DSBD, 2018. Annual report 2017/18. http://www.dsbd.gov.za/?wpdmpro=dsbd-201718-annual-report-final Accessed 30 January 2019.

- DSBD, 2019. 2016/2017 annual review of small businesses and cooperatives South Africa. http://www.dsbd.gov.za/?wpdmpro=2016-annual-review-of-small-businesses-and-cooperatives-south-africa Accessed 31 January 2019.

- DTI (Department of Trade and Industry), 1995. White paper on national strategy for the development and promotion of small business in South Africa. DTI, Cape Town.

- DTI, 2003. Integrated small-enterprise-development strategy. DTI, Pretoria.

- DTI, 2004. Review of ten years of small business support in South Africa 1994–2004. DTI, Pretoria.

- DTI, 2008. Annual review of small business in South Africa 2005–2007. DTI, Pretoria.

- Fang, H, Randolph, RVDG, Memili, E & Chrisman, JJ, 2016. Does size matter? The moderating effects of firm size on the employment of nonfamily managers in privately held family SMEs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 40, 1017–39. doi: 10.1111/etap.12156

- Ferreira, E, Strydom, J & Nieuwenhuizen, C, 2010. The process of business assistance to small and medium enterprises in South Africa: Preliminary findings. Journal of Contemporary Management 7(1), 94–109.

- Finscope, 2010. Finscope South Africa small business survey. http://www.finmark.org.za/publication/finscope-south-africa-small-business-survey-2010-report Accessed 18 September 2015.

- FSPBusiness, 2017. SARS will interview you when you apply for vat registration. http://fspbusiness.co.za/articles/vat/sars-will-interview-you-when-you-apply-for-vat-registration-take-note-of-the-six-pieces-of-information-it-wants-to-know-or-it-will-reject-your-application-6858.html Accessed 29 August 2017.

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2016. South African report 2015/2016. Is South Africa heading for an economic meltdown? University of Cape Town and Development Unit for new enterprise, Cape Town.

- Gherhes, C, Williams, N, Vorley, T & Vasconcelos, A, 2016. Distinguishing micro-businesses from SMEs: A systematic review of growth constraints. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 23(4), 939–63. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-05-2016-0075

- Gray, D & Jones, KF, 2016. Using organisational development and learning methods to develop resilience for sustainable futures with SMEs and micro businesses: The case of the ‘business alliance. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 23(2), 474–94. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-03-2015-0031

- Herrington, M, Kew, P & Mwanga, A, 2017. Global entrepreneurship monitor South Africa 2016–2017 report. University of Cape Town.

- Loader, K & Norton, S, 2015. SME access to public procurement: An analysis of experiences of SMEs supplying the publically funded UK heritage sector. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 21(4), 214–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pursup.2015.02.001

- Loeprick, J, 2009. Small business taxation reform to encourage formality and firm growth. Investment Climate in Practice 1, 1–7. https://smartlessons.ifc.org/uploads/smartlessons/20101209T141456_Inpracticeno1.pdf Accessed 27 May 2011.

- Lignier, P, 2011. Re: Comparative compliance costs project. [E-mail from:] Lignier, P. ([email protected]) [E-mail to:] Smulders, S.A. ([email protected]) 19 August 2011.

- Maduku, DK, Mpinganjira, M & Duh, H, 2016. Understanding mobile marketing adoption intention by South African SMEs: A multi-perspective framework. International Journal of Information Management 36(5), 711–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.04.018

- Makanyeza, C & Dzvuke, G, 2015. The influence of innovation on the performance of small and medium enterprises in Zimbabwe. Journal of African Business 16(1–2), 198–214. doi: 10.1080/15228916.2015.1061406

- Maye, M, 2014. Small business in South Africa: What the Department of Small Business Development can do to stimulate growth. CPLO Occasional Paper 35, September.

- National Credit Regulator, 2011. Literature review on small and medium enterprises’ access to credit and support in South Africa. Underhill Corporate Solutions, Pretoria.

- National Planning Commission, 2012. National development plan 2030. http://www.gov.za/issues/national-development-plan-2030 Accessed 29 September 2015.

- NEF (National Empowerment Fund), 2017. The DTI agencies. http://www.thedti.gov.za/agencies/nef.jsp Accessed 9 March 2017.

- Nieuwenhuizen, C, 2019. The effect of regulations and legislation on small, micro and medium enterprises in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 36(5), 666–77. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2019.1581053.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2017. Small, medium, strong trends in SME performance and business conditions. OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Office of the Premier, 2014. President Jacob Zuma announces member of the Executive – 25 May 2014. http://premier.nwpg.gov.za/content/president-jacob-zuma-announces-members-national-executive-25-may-2014 Accessed 27 August 2017.

- Parliamentary Monitoring Group, 2015. Department of Small Business Development on its 2014/15 annual report; Auditor-General & DPME inputs. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/21608/ Accessed 27 August 2017.

- Parliamentary Monitoring Group, 2017. Department of Small Business Development on its 2015/2016 annual performance report, with minister. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/23947/ Accessed 21 June 2017.

- Parliamentary Monitoring Group, 2018. Department of Small Business Development 2017/18 annual report, with AGSA & minister and deputy minister present. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/27199/ Accessed 24 January 2019.

- Rogerson, C, 2004. The impact of the South African government's SMME programmes: A ten-year review (1994–2003). Development Southern Africa 21(5), 765–84. doi: 10.1080/0376835042000325697

- Rogerson, C, 2008. Tracking SMME development in South Africa: Issues of finance, training and the regulatory environment. Urban Forum 19(1), 61–81. doi: 10.1007/s12132-008-9025-x

- SAICA (South African Institute of Chartered Accountants), 2017. 2016 SMME insight report. https://www.saica.co.za/Default.aspx?TabId=2830&language=en-ZA Accessed 25 June 2017.

- SARS (South African Revenue Service), 2017a. Tax guide for micro businesses. http://www.sars.gov.za/AllDocs/OpsDocs/Guides/LAPD-TT-G01%20-%20Tax%20Guide%20for%20Micro%20Businesses%20-%20External%20Guide.pdf Accessed 27 August 2017.

- SARS, 2017b. VAT 404 – guide for vendors. http://www.sars.gov.za/AllDocs/OpsDocs/Guides/LAPD-VAT-G02%20-%20VAT%20404%20Guide%20for%20Vendors%20-%20External%20Guide.pdf Accessed 27 August 2017.

- SBP, 2014. Examining the challenges facing small businessess in South Africa. Issue paper 1 2014. SBP, Johannesburg.

- SEDA (Small Enterprise Development Agency), 2017. SEDA an agency of the department of small business development which provides non-financial support to small enterprises and co-operatives. http://www.seda.org.za/Pages/Home.aspx Accessed 9 March 2019.

- SEFA (Small Enterprise Finance Agency), 2017. The Small Enterprise Finance Agency. http://www.sefa.org.za/ Accessed 9 March 2017.

- Shibia, A & Barako, D, 2017. Determinants of micro and small enterprises growth in Kenya. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 24(1), 105–18. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-07-2016-0118

- SME South Africa, 2016. 4 Edu-preneurs on teaching entrepreneurship to young students. http://www.smesouthafrica.co.za/16687/Attempting-to-alleviate-South-Africas-poor-performance-in-entrepreneurship/ Accessed 30 March 2017.

- Smulders, S, Stiglingh, M, Franzsen, R & Fletcher, L, 2012. Tax compliance costs for the small business sector in South Africa – establishing a baseline. e-Journal of Tax Research 10(2), 184–226.

- South African Government, 2016. Minister Lindiwe Zulu: Small business development dept budget vote 2016/17. http://www.gov.za/speeches/address-minister-small-business-development-ms-lindiwe-zulu-mp-occasion-delivering-budget Accessed 21 June 2017.

- Statistic Solutions, 2017. Statistic solutions: Advancement through clarity: Kruskal-Wallis test. http://www.statisticssolutions.com/?s=kruskal+wallis Accessed 21 June 2017.