ABSTRACT

There is still a need for appropriate livelihood strategies to improve livelihoods of small-scale fishers, despite several roles the African inland fisheries play to fishers’ wellbeing. This study assessed the nexus between small-scale fishing and fishers’ livelihoods at Lake Itezhi-Tezhi, Zambia. Using the mixed-methods approach under a sustainable livelihood framework, findings revealed the fishing income was insufficient to improve their livelihood assets due to the low fish catches per fisher. Deficiency in fishing income was compounded by fishers’ vulnerability to shocks caused mainly by the effects of the closed fishing season and crop/livestock production failures. As such, the study suggests, among other strategies, the support of fishery stakeholders towards alternative income sources and development of a livelihood-inclusive fisheries policy framework to help enhance the livelihoods of fishers at Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery. Beyond this lake fishery, this study contributes similar strategies as lessons for addressing the fishers’ livelihood challenges and promoting sustainable fishing.

1. Introduction

In many parts of Africa, communities near perennial rivers and water bodies rely on small-scale fishing for their livelihoods (FAO, Citation2016; Lynch et al., Citation2017). The small-scale inland fishing sector plays a vital role in the provision of food, nutrition, income, and employment for local livelihoods (Welcomme et al., Citation2010; Weeratunge et al., Citation2014; FAO Citation2016). The sector also provides basic needs for poorer households in unforeseen circumstances (Béné, Citation2006; Welcomme et al., Citation2010). Income from fishing is critical in meeting household needs and securing safety nets among local small-scale fishers (Béné, Citation2006; Ngoma, Citation2010; Isaacs, Citation2012). The Sector has also empowered women with opportunities to contribute to household food security and income through fish processing and trading (Welcomme et al., Citation2010; Hauzer et al., Citation2013; Lynch et al., Citation2017). However, the small-scale fishing sector still experiences challenges despite the significant role it plays.

In Africa, the small-scale fishing sector has been frequently overlooked by policymakers in rural development planning, rural economic development, and pro-poor growth policy formulation, which is mainly due to the lack of reliable data on its economic contribution (Béné et al., Citation2009; Weeratunge et al., Citation2014; De Graaf et al., Citation2015). This neglect of the sector has resulted in most inland fisheries resources being overexploited, thus threatening the sustainability of these resources in the absence of appropriate legislation, policies and functional resource governance arrangements (Kébé & Muir, Citation2008; Kleibe et al., Citation2015; Harper et al., Citation2017). Further, the open-access nature of most inland fisheries has resulted in overfishing and reduced fish catches, thus negatively affecting the fishers’ fishing income in the absence of alternative livelihood strategies (Yuerlita, Citation2013). Having been overlooked for a long time, the sector has also predisposed the small-scale fishers’ livelihoods to vulnerability by various stresses and shocks, such as increasing population of fishers, water level fluctuations (climate change effects), illegal fishing practices, and limited access to other income sources (Mills et al., Citation2011; Yuerlita, 2013). The high level of vulnerability could be the reason why Belhabib et al. (Citation2015) in their study of fisheries in West Africa also affirmed the small-scale fisheries sector to be more of an activity of last resort than a source of sustainable livelihood. However, contrary views exist in literature to this affirmation because of several factors at play (Allison & Ellis, Citation2001; Béné et al., Citation2003; Béné & Friend, Citation2011; Onyango, Citation2011). As such, the debate continues on the relationship between fishers’ livelihoods and sustainable fishing.

According to Béné & Friend (Citation2011), there was no stable causal relationship between fishing and the fishers’ vulnerability and poverty, hence the debate. Besides, Béné et al., (Citation2003) had earlier stated that the relationship between fishing and poverty level of fishers’ households was a complex one. This complexity is because of different factors, such as geographical location (country and fishery-specific), economic status of fishers, lack of education, lack of entitlement to the fisheries, lack of infrastructure, resource governance failure, lack of policy and legislation, and limited market access, impacted on livelihoods and fishing (Béné et al., Citation2003; Béné & Friend, Citation2011; Kadfak, Citation2019).

Further, given the negative impact of the neglect of the small-scale fisheries sector, voluntary guidelines for securing sustainable small-scale fisheries (the SSF Guidelines) in the context of food security and poverty eradication were endorsed in 2014 by over 100 countries under the auspices of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). These guidelines are intended to guide governments and other stakeholders to collaborate and ensure sustainable fisheries for the benefit of small-scale fishing communities and society at large (FAO, Citation2016). Despite the endorsement of these SSF Guidelines, implementation in many developing countries has been very slow, hence exerting little or no impact on fishers’ livelihoods (FAO, Citation2016). Additionally, even where African governments have developed policies that promote small-scale fishers’ participation in the governance of fisheries resources, weak implementation has resulted in their weak contribution to sustainable livelihoods among small-scale fishers (Béné et al., Citation2008; Nunan et al., Citation2015). The central government top-down governance approach in these countries has been responsible for the weak implementation of these policies as the approach has had no mandate of devolving responsibilities, power and authority to the local fishing community (Neiland et al., Citation2005b; Neiland et al., Citation2005a; Ogutu-Ohwayo & Balirwa, Citation2006; Béné et al., Citation2008; Lawrence, Citation2015). Further, the issue of sustainable fishing and fishers’ livelihoods was also fishery and country-specific due to the perculiarity of each fishery and country (Isaacs, Citation2012). As for Zambia's fisheries, there is little literature that highlight strategies to enhance the livelihoods of small-scale fishers as a means of mitigating the unsustainable fishing and overexploitation of the fisheries resources.

Zambia is a landlocked country that is endowed with nine major inland fisheries (SADC, Citation2016), with small-scale fishing being the main activity. Inland small-scale fishing involves low investment by the individuals who fish in lakes, rivers, streams, wetlands, and reservoirs, thus making it affordable for people with low incomes (FAO, Citation2009). In Zambia, poor people comprise 76% of the rural population (CSO, Citation2014), and small-scale fishers are part of this population.

In 2014, the Zambian fisheries sector supported about one million people, approximately 6.5% of the entire population (DoF, Citation2014a). However, the fish consumption rate reduced from 12 kg per capita per annum in the 1970s to 7.7 kg in 2012 (Kefi & Mofya-Mukuka, Citation2015), which is probably due to the open-access nature of the fisheries that led to the overexploitation of their resources (DoF, Citation2015). Kefi & Mofya-Mukuka (Citation2015) also stated that Zambia's overexploited resources seem to have negatively affected the small-scale fishers’ livelihoods, hence the reported high poverty levels among them.

To address the issue of resource overexploitation that had a bearing on the small-scale fishers’ livelihoods, pieces of legislation were included in the amended Fisheries Act, No. 22 of 2011of the Laws of Zambia (Government of Zambia, Citation2011). These legislative pieces mandated the local fishing community to participate in the governance process of the fisheries. That entails incorporating fishers into the Fisheries Management Committee, a decision-making committee designed to preside over the governance and management of fisheries resources, as active members. This arrangement was meant to enhance sustainable fishing in the country's water bodies, thereby addressing the livelihoods of small-scale fishers (Haambiya et al., Citation2015; Kefi & Mofya-Mukuka, Citation2015). However, the impact of this legislation on the livelihoods of fishers’ households was still unknown given the continuation of fisheries resource overexploitation in most fisheries.

Considering the numerous factors that affect the small-scale fishers’ livelihoods, country and fishery-specific studies are still needed to explore the relationship between their livelihoods and sustainable inland fishing (Lynch et al., Citation2017). This study aimed at contributing to this debate. This knowledge is meant to help mitigate the unsustainable fishing and overexploitation of the fisheries resources for the benefit of the fishers’ livelihoods. The objective of this study was to assess the contribution of small-scale fishing on Lake Itezhi-Tezhi to the livelihoods of local fishers’ households, the extent of their vulnerability, the livelihood coping strategies employed, the impact of legislation on these livelihoods, and the recommendations thereof. The objective was addressed by answering the following research questions:

What is the contribution of income from fishing to fishers’ livelihood assets?

To what extent has stakeholders, vulnerability, and legislation affected the fishers’ livelihoods and their fishing?

What are the fishers’ livelihood strategies, and how have these strategies affected their livelihoods?

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study site

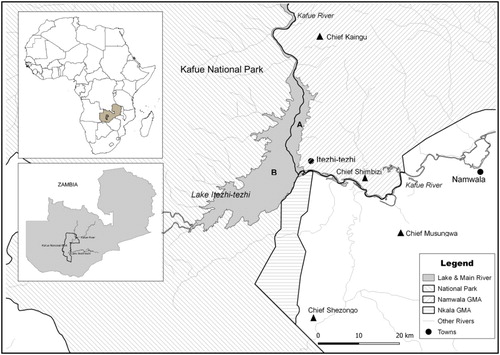

Man-made Lake Itezhi-Tezhi () lies on the Kafue River at 150 46´S and 260 02´E (Swedish Consultants, Citation1971). A dam that formed the lake of 392 km2 with a maximum depth of 55 m was built in 1977 (Godet & Pfister, Citation2007). Until hydro-power generation began in 2016, the lake stored and supplied water for the Kafue Gorge Upper Power Station about 260 km downstream (Godet & Pfister, Citation2007). No studies have been done at the lake to indicate whether or not fluctuations in the water level of the lake affected fish catches.

During the dam construction phase, employment was created for people from different parts of the country. Upon completion of the dam, the lake became an essential source for the livelihoods of the majority of the people who were now unemployed and had settled by the lake (Old retired fisher, personal communication, July 12 2016).

A larger area of the lake lies in the Kafue National Park (). The lake also shares borders with the Game Management Areas, Namwala and Nkala, and the Itezhi-Tezhi town (). The Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) and the Department of Fisheries (DoF) collaborate in conducting law enforcement activities on the lake such as control of illegal fishing practices and implementation of the closed fishing season programme (Ngoma Citation2010). Fishers access fishing sites during the fishing season (March–November) through park entry permits issued by the DNPW and fishing licences issued by the DoF. The closed fishing season is from December to February (DoF, Citation2014b), and fishers look for alternative sources of income during this period.

The lake is situated within the Itezhi-Tezhi district, which lies 347 km from Lusaka, the capital city. In the 2000–10 intercensal period, the Itezhi-Tezhi district had the fastest annual population growth rate of 4.8% in the Southern Province of Zambia (CSO, Citation2014). The district accommodates government offices, health centres, trading facilities, and housing units. Available income-generating activities for the people in the district include small-scale fishing, small-scale farming, livestock rearing, and trading in addition to formal employment in government departments, the electricity company, and the lodges around the lake (DoF, Citation2014b).

During the study period, the fishing community comprised immigrantFootnote1 and residentFootnote2 fishers. These fishers resided in the chiefdoms of four prominent chiefs, namely, Kaingu, Shimbizi, Musungwa, and Shezongo on the northern, eastern, and southern sides of the lake ().

2.2. Sustainable livelihood approach

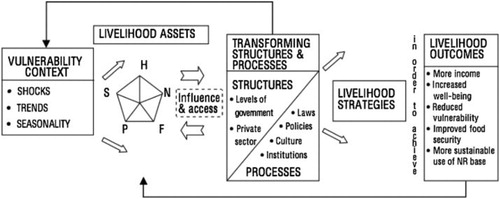

This case study regarding Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery is framed under the Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA). The SLA fits well with organisations and interventions dealing with rural communities, like the Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishing community, in developing countries and is attributed much to Robert Chambers’ work on the ‘wealth of the poor’ and participatory methodologies (May et al., Citation2009). The SLA is mainly centred on wanting to understand how different people in different environments live, how and why they make the choices that they make concerning their livelihoods (Scoones, Citation1998; Levine, Citation2014). Various livelihood frameworks exist (see De Satgé Citation2002), but the current study considered the Sustainable Livelihood Framework () by the Department for International Development (DFID, Citation1999). This framework helps to understand the different aspects of local people's livelihoods holistically, that is, their assets or capital (human, natural, financial, physical and social capital) (), the influence of structures (organisations) and processes (institutions, rules, customs, laws, and culture), their vulnerability to different shocks, livelihood strategies employed to overcome them, and the livelihood objectives being pursued to enhance such livelihoods (Scoones, Citation1998).

Figure 2. Sustainable Livelihood Framework (Source: DFID (Citation1999)).

Table 1. Five livelihood assets or capacities.

The SLA has also been widely used as a framework and a guide for local, national and regional policy formulation concerning local fishing communities in addressing multiple livelihood issues, thereby promoting sustainable livelihoods and fisheries resource utilisation (Allison & Ellis, Citation2001; Allison & Horemans, Citation2006; Weeratunge et al., Citation2014; McClanahan et al., Citation2015). In this study, the SLA provides a methodological and analytical framework to show the influence of income from fishing on fishers’ livelihood assets or capital, the impact of their vulnerability to various shocks, their livelihood coping strategies, and the implications of legislation and policy on such aspects and on the resources of the lake fishery.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

2.3.1. Sampling and data collection methods

Data collection was conducted at the study site () from March 2016 to July 2016 using the sequential (exploratory and explanatory) mixed-methods approach to obtain both quantitative and qualitative data (Schram, Citation2014). In sequential approaches, data collection is done in sequence, so that the results of one dataset (from focus group discussions (FGDs) for instance) influence the data collection for the next dataset (for a survey for instance) (Creswell, Citation2014). Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery has approximately 40 fishing campsFootnote3 and fishing villagesFootnote4, also referred to as fishing locations in this study, and comprise several heads of households. Because the fishing community population is heterogeneous (i.e. every element of the study population did not match all the characteristics of the predefined criteria), quota sampling was used (Alvi, Citation2016). Based on the location of the fishing sites, the different distances to the fishing sites from the homesteads and the different behavioural patterns and means of accessing the fishing sites, the lake with its fishing locations was divided into three homogenous research strata. Therefore, to select the total sample size of fishing locations in each stratum, the Proportional Quota Sampling (Alvi, Citation2016) was the most appropriate at the time of data collection. Probability sampling (stratified random sampling) was not possible as most of the fishers were not available on site in some fishing locations of each stratum. Therefore, Quota Sampling helped to determine the representative sample sizes of fishers and fishing locations (), proportional to the population of fishers and fishing locations.

A total of 12 out of 40 fishing locations within the strata, representing 30% of the total number, were purposefully selected from where surveys and FGDs with fishers were conducted (). The selection was purposefully done because only 19 out of 40 fishing locations had fishers on site at the time of the study.

A survey with questionnaires was conducted based on a sample of 451 adult household fishers (≥18 years old). The selection of the respondents (fishers) was based on a confidence level of 95%, from a total of 1800 fishers in the three strata (). The population of fishers was arrived at from undocumented figures gathered by the principal researcher from traditional authorities for fishing villages and chairpersons for fishing camps. This exercise was conducted a month before the survey.

Table 2. Composition of the strata for Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery.

A snowball sampling method was used in each selected fishing location within each stratum to select the required number of fishers (Alvi, Citation2016). Although subject to sampling bias, this sampling method was the most appropriate for identifying fishers in the fishing locations. There was neither a specific list of fishers with the traditional authorities nor with most chairpersons to select them from randomly. Further, the fishers were not on site in most fishing locations. Of all the respondents captured, only eight were female household heads. There was a 100% response rate from the fishers as the questionnaires were physically administered to each one of them. A pilot study using 20 questionnaires was conducted on the same fishers in order to pre-test the reliability, validity and applicability of the instrument (Sheatsley, Citation1983).

Mixed questionnaires, that is, questionnaires which comprised both closed-ended and open-ended questions (Ghosh, Citation1992), was used through which data regarding certain identified aspects of the fishing community were collected. The questionnaire focused on fishers’ forms of livelihood assets or capital, incomes, expenditures, income sources, livelihood activities and income contributions of other household members, fish status in the fishery, accessibility to social amenities, livelihood strategies employed, fish market, and vulnerability of fishers.

Focus group discussions were also used because of the significant interactions and perceptions that they could provide on the subject matter peculiar to the fishing community (Bless et al., Citation2013). Through a sequential exploratory approach across all the strata, the general data collected through FGDs helped to structure questionnaire questions to capture specific details on a particular issue from individual fishers (Creswell, Citation2014). This technique of data collection ensured uniformity, validity and reliability of data (Babbie and Mouton, Citation2001). For fruitful discussions, each consisted of not more than ten purposefully selected adult respondents (≥18 years old) based on being involved in fishing or fishing-related activities (Bless et al. Citation2013). Three of the FGDs in stratum three (fishing villages) had a mixture of men and women and this helped to capture views from both genders.

Furthermore, 17 semi-structured interviews with 12 key stakeholders in the fishery (government departments, traditional leaders, the District Commissioner’s Office, local government, non-governmental organisations, the fishers’ association, and private firms) were conducted in order to gather additional information on the subject. However, not all stakeholders had the same level of interest in the wellbeing of the fishers. Primary stakeholders assumed a more active role in the governance and management of the fisheries resources and livelihood needs of fishers. Secondary stakeholders played consultative roles and provision of other needed resources in the process (Borrini-Feyerabend et al., Citation2013). For this study, primary stakeholders included fishers, government agencies, such as the DoF and the DNPW, traditional authorities, the Fishermen and Fish Traders Association (FFTA), and a non-governmental organisation (NGO). Secondary stakeholders comprised government agencies, such as the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Livestock, the Itezhi-Tezhi district council (local government), the District Commissioner's office, and two private firms.

Through a sequential explanatory approach, the interviews were also meant to explain and confirm earlier views gathered from fishers through the FGDs and questionnaires. The approach ensured the validity and reliability of data being collected for the study (Ghosh, Citation1992; Creswell, Citation2014). As such, purposive sampling was used to select the interviewees based on their knowledge of and level of interaction with fishers and their fishing business. The interviews and FGDs focused on the contribution of household members to household livelihoods, social relationships among different ethnic groups, levels of stakeholder support towards fishers’ livelihoods, perceptions of the causes of the decline in fish catches, and the extent of fishers’ vulnerability to shocks.

The household income recall period was every month over one year. For the performance and activities of the Fishermen and Fish Traders Association (FFTA) and other stakeholders, the recall period was five years. Regarding the fish catch status, the period was five to ten years.

2.3.2. Data analysis

Qualitative data collected through the FGDs and interviews were analysed based on themed content analysis of transcribed scripts (Bless et al., Citation2013). Atlas.ti software was used for the analysis. Quantitative data collected through the questionnaires were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics (Bless et al., Citation2013) with the aid of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 20. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to identify the main characteristics of the fishers. Inferential statistics were used to assess whether or not relationships existed between specific fishers’ characteristics and fishing income. For instance, chi-square (Pearson’s χ2) and maximum likelihood (MLχ2) coefficients together with Cramer's V (v) were used to determine the extent of associations between two nominal or ordinal variables (fishing income levels and other income sources) (McHugh, Citation2013).

Finally, ordinal logistic regression predicted the extent to which the set of independent variables influenced the dependent variables (fishing income, expenditures, and physical assets) (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Citation2008). Reliability and validity were addressed by the use of different sources of data (triangulation) (Kohn, Citation1997) and a Quota sampling technique (Shi, Citation2015).

3. Results

3.1. Fishing income contribution and status of fishers’ livelihood assets

3.1.1. Human capital

Regardless of the research strata, the fishing community was mostly composed of fishers who had not gone beyond primary education, who were married and who were within the age group of 18–40 years (). On average, each household had 4.5 members. The majority of fishers residing in the fishing locations of Lake Itezh-Tezhi were migrants from other places within Zambia (). The majority of immigrants were in strata two and three (i.e. 90% and 93% respectively), with stratum one demonstrating 61% of immigrants.

Table 3. Characteristics of human assets in the fishing community (n = 451).

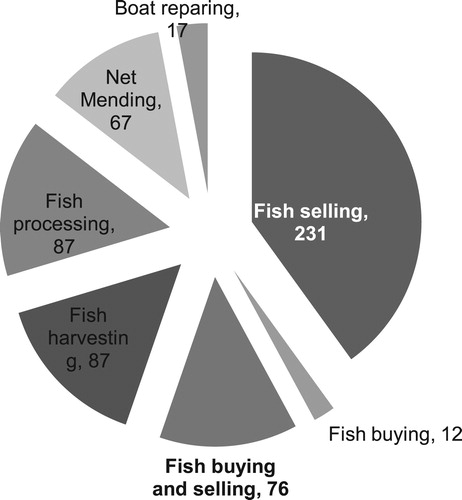

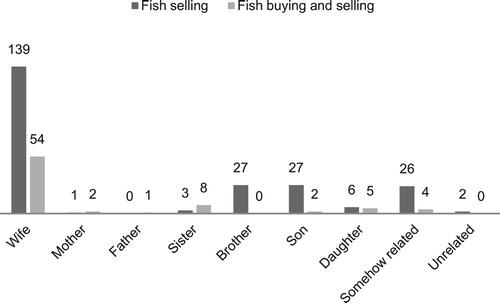

Of the 1 916 members comprising the fishers’ households, 577 members (30.1%) were involved in fishing-related activities. See . Of these, 231 members (40%) were fish sellers only and 76 members (13.2%) were fish buyers-cum-fish sellers. See . However, of the 231 fish sellers and the 76 fish buyers-cum-fish sellers, 60.2% (139) fish sellers and 71.1% (54) fish buyers-cum-fish sellers were fishers’ wives. See . The fishers’ wives played a significant role in contributing to household income through fish selling. However, the FGDs revealed that most of the married fishers worked together as couples to earn their household income through fish trading.

3.1.2. Natural capital

The survey revealed that 98% of all fishers in all the research strata depended on fish as a significant source of income, and over 90% of fishers consumed fish daily. Over 77% of fishers in all the strata used firewood as a source of energy for cooking. Over 65% of fishers in all the strata had access to pieces of land under the customary laws of land acquisition. About 80% of fishers in strata one and two had access to clean drinking water, but only 45% of fishers in stratum three had such access.

3.1.3. Financial capital

The Ordinal Logistic Regression () revealed that only the fishers’ education levels and the location of their fishing areas influenced their fishing income levels. Fishers who were in research strata one and two tended to earn more income through fishing than those in stratum three. The scenario implies that strata one and two (comprising fishing camps with fishers focused on fishing alone) had most of the fishers who earned more than $200/month compared with stratum three (comprising fishing villages with fishers also involved in other activities) who had most of the fishers who earned less than $100/month. Furthermore, fishers who had some education (either primary or secondary education) tended to earn more fishing income than those who had no education ().

Table 4. Factors that influenced fishing income levels among fishers (n = 451; R2 = 0.06; p < 0.001).

Fishing was the major source of income for fishers in all the research strata (). While controlling for research strata, the chi-square analysis showed that there was no significant association in the three research strata between income earned through fishing and income earned through each of the non-fishing activities, that is, crop production, livestock production, and others (). As such, income earned through fishing had no bearing on how non-fishing income was generated. Additionally, from the survey of the 274 fishers (60.7%) who had engaged in non-fishing income sources across all the strata, only 13.4% of the fishers confirmed earning income from crop production (maize and sweet potatoes) within the range of $0.1−$200 per year, 5.1% from livestock production (chickens) and 6.2% from additional income sources within the same range. The majority of the fishers felt that the contribution to the household income of these alternative sources of income was not significant compared with the income gained from fishing ().

Table 5. Percentages of fishers based on major income sources and income ranges.

With regard to the 1 916 fisher household members, 80.2% did not make any financial contribution to the household. This lack of contribution was because these members were too young or too old to work, or were pupils or students. Thus, only 19.8% contributed income through fish selling, self-employment, formal employment, and small grants from government, churches, and non-governmental organisations. In monetary terms, 7.2%, 6.1%, 3.7% and 2.8% of the 1 916 household members contributed less than $50/month, $50.1−$100/month, $100.1−$200/month, and more than $200/month respectively to household income.

3.1.4. Physical capital

Fishers with less fishing income were more likely to own mud and thatched houses than fishers earning more fishing income (). As the fishing income of fishers increased, fishers were more likely to own unburnt and burnt brick houses with iron sheet roofs. Furthermore, fishers who earned a greater fishing income tended to own more fishing canoes and nets and household furniture and to possess solar panels for electrifying their homes, electronic information gadgets, and transportation vessels. However, fishing income made less than a 10.6% (R2) statistically significant contribution to the regression model for all the physical assets under study ().

Table 6. Ordinal logistic regression prediction of whether or not fishers’ ownership of physical assets was dependent on different levels of fishing income. Reference fishing income = more than $200; n = 451; * Significant (Sig.) at p < 0.05 or ** p ≥ 0.001, ns: Not significant at p ≥ 0.05.

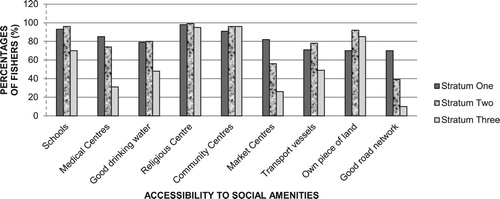

The survey showed that over 55% of the fishers in research strata one and two had access to almost all social amenities, while less than 50% of fishers in research stratum three did not have easy access to medical centres, clean drinking water, market centres, transport vessels, and reliable roads (). Fishers in stratum three (FGDs) attributed their difficulty in accessing medical and market centres to the considerable distances of these facilities from their fishing villages. Unsafe drinking water from wells and the lake were the fishers’ primary water sources in stratum three (FGDs). Poor access to vehicles (transport vessels) was attributed mainly to the poor road network ().

3.1.5. Social capital

Despite fishers in all the strata indicating the availability of religious and community centres meant for developing the fishing community and improving people's livelihoods, participation at these centres was low (). Of the 451 fishers surveyed, only 66 (14.6%) indicated being registered members of committees and associations available in the community. These institutions ranged from the FFTA to religious, political, educational, agricultural, traditional, youth, and village committees. Only 22 (4.9%) fishers surveyed were registered members of the FFTA, an association that deals with the welfare of all fishers who trade on the lake. Low membership indicates that the majority of fishers are uninterested in the operations of the FFTA. The survey data was supported by the FGDs, indicating that the FFTA did very little to attend to fishers’ livelihood needs.

Social interactions seemed to be lacking among the majority of fishers in the fishing community. However, results from both the FGDs and the survey indicated that regardless of ethnicity, there were cordial social relationships among the fishers while fishing.

3.2. Organisational (stakeholders) support

Of the 451 fishers surveyed, 74% considered the DoF to be mandated to govern and manage the fisheries’ resources. However, FGDs in all the strata revealed that the DoF could not address their livelihood demands. The fishers in the FGDs also revealed that most of the other stakeholders had not offered the needed support to enhance their livelihoods in the fishing community. For instance, fishers indicated that they had no access to financial support in terms of loans from financial lending organisations or government to boost their other income-generation ventures. However, most of these organisations (stakeholders) contended that they did not provide much support because fishers seemed institutionally disorganised in their operations.

3.3. Vulnerability and livelihoods

3.3.1. Vulnerability to food shortages and price fluctuations

Regardless of fishing income levels, over 80% of the fishers had experienced food shortages in the last five years. The shortages occurred mostly during January and February, which coincided with the closed fishing season. During this period, fishers’ income was cut off, negatively affecting their food security and livelihoods. Additionally, income from fish sales was negatively affected by market prices during the fishing season due to the high supply of fish on the markets.

3.3.2. Vulnerability to fishing duration and fish catches

Fishers currently take longer to meet their fishing target during the peak harvesting season than ten years ago. Presently, reaching this fish catch target takes about 51 ± 25 days while ten years ago, it took about 20 ± 14 days. The increased fishing duration was attributed to low fish catches in the lake by 84% of fishers. Low fish catches were attributed to the high influx of fishers on the lake over the past five to ten years (FGDs in all strata). Headmen interviews suggested the influx of fishers came about because most village headmen allowed any Zambian fisher to settle in their villages; there were no severe restrictions for the settlement of fishers.

3.3.3. Vulnerability to other factors

From the survey of the 142 (31.5%) fishers-cum-crop farmers, 78.2% had their crop yields affected by inadequate or excessive rainfall over the past five years, and 47.2% had their crop yields affected by expensive inputs. In addition, of 169 (37.5%) fisher-cum-livestock farmers, 20.8% had their livestock production affected by disease outbreaks and 15.5% by predators. Almost half of the FGDs highlighted other significant shocks such as exposure to dangerous wild animals during fishing expeditions, fluctuations in fish catches due to hot and cold seasons, and high transport costs to fish markets.

3.4. Livelihood coping strategies and their impact

3.4.1. Fish selling locations

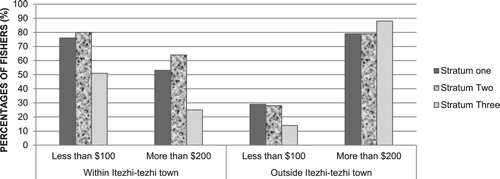

Apart from being involved in crop and livestock production as livelihood strategies by a few fishers, selling fish in markets other than local markets to obtain a better price was a coping strategy. In all the strata, the majority of fishers with less fishing income preferred to sell their fish within Itezhi-Tezhi town, while those with a higher fishing income sold outside Itezhi-Tezhi town (). Such preference in fish selling location, especially for stratum three, was reflected in the level of fishing income earned; 51% of fishers with a lower fishing income sold within Itezhi-Tezhi town compared with 25% of fishers with a higher fishing income. Only 14% of fishers with a lower fishing income sold outside Itezhi-Tezhi town compared with 88% of fishers with a higher income ().

3.4.2. Strategic household expenditures

The less the income of the fishers through fishing, the less fishers are likely to spend on foodstuff (). The low-income earners had fewer than three meals per day as a livelihood coping strategy. In addition, less of the fishing income was spent on cetain non-food goods and services such as school fees for children or relatives, transport, and energy sources (). However, fishing income only made less than a 3.3% (R2) statistically significant contribution to the regression model for all the fishers’ expenditure levels under study ().

Table 7. Ordinal logistic regression predictions of whether or not fishers’ expenditures were dependent on different levels of fishing income. Reference for fishing income = more than $200; n = 451; * Significant at p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.001, ns: Not significant at p ≥ 0.05.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Income and livelihood assets

In many African countries, inland small-scale fishing contributes to fishers’ livelihoods. Small-scale fishing provides income to access goods and services such as food, health, education, clothing, fishing inputs, and agricultural labour (Béné & Heck, Citation2005; Béné et al., Citation2009; Welcomme et al., Citation2010). The current study confirmed this view and demonstrated that income from fishing had a bearing on the fishers’ livelihoods depending on the levels of income earned. The higher the income through fishing, the more it empowered fishers to invest in several physical assets (capital) and to access goods and services for their households. This study also showed that fishing income alone was not enough to enhance fishers’ livelihoods. In addition, other factors such as the vulnerability of fishers to various shocks affected their livelihoods.

Education level influenced the level of fishing income. Fishers with a relatively higher education earned a greater fishing income per month. This scenario reinforces the need for education through consistent awareness-raising and capacity-building programmes organised by stakeholders (Allison & Horemans, Citation2006; FAO, Citation2015) to empower fishers with knowledge and skills. Capacity-building programmes could range from financial and business management to sustainable fishing techniques.

The current study agrees with the studies of Ngoma (Citation2010) and Sililo (Citation2016) conducted on the Kafue floodplain fishery in Zambia that showed that immigration of fishers from other parts of Zambia contributed to the reduction in fish catches per fisher. In the current study, low fishing income was also attributed to the influx of immigrants. A review of certain African and Asian fisheries by Béné (Citation2003) and a study of West African fisheries by Binet et al. (Citation2012) also showed that migration of fishers into fisheries was a common problem that usually resulted in overexploitation of fisheries’ resources and a negative impact on the livelihoods of the local fishing communities.

The low fish catches experienced by the Itezhi-Tezhi fishers seemed to have limited the fishers’ ability to earn more income for further investments and to meet household needs. The other sources of income did not contribute sufficiently to total household income, and this was attributed to a lack of stakeholders’ support in making these alternative sources viable. Regarding the presence of stakeholder support as recommended by the FAO (Citation2015) in its voluntary guidelines for securing sustainable small-scale fisheries, the current study concurs and states that sustained technical and financial support for fishers by identified stakeholders at Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery is crucial. Such support would enhance fishers’ crop and livestock production and other business ventures, thereby improving their income levels.

Another aspect is the role of women in income contribution to household food security and income through fish trading (Kleiber et al., Citation2015; Harper et al., Citation2017). The current study argues that if local women were empowered by formalising their fish trading through a deliberate policy framework, they would exert a more positive impact on the livelihoods of their households. Policy-driven fish trading for women would perhaps help them to access credit facilities to venture into new businesses, resulting in more income for household use. Huchzermeyer (Citation2013) alluded to the same in his study on the fishery at Lake Bangweulu floodplain in Zambia although the focus in the research was on local fish traders regardless of gender.

4.2. Vulnerability, governance, legislation, and policy

Vulnerability incorporates exposure to shocks, risks, and susceptibility (Béné, Citation2009). In the current study, crop and livestock production failures, a closed fishing season of three months, fluctuating fish catches due to changes in yearly seasons, and high transport costs to distant markets were some of the shocks that negatively affected fishers’ livelihoods. The closed fishing season demonstrated a greater negative impact on the fishers since it usually coincided with their low or absent crop and livestock production. The impact of vulnerability on small-scale fishers was also reported by Allison & Ellis (Citation2001), Béné (Citation2009), and Ngoma (Citation2010) who associated higher reliance on a single source of income such as fishing with higher vulnerability to risks and poverty, particularly in poor households. In agreement with the argument of Belhabib et al. (Citation2015), the extent of most fishers’ vulnerability in the current study seemed to have contributed to fishing being a last resort activity rather than a source of sustainable livelihood.

Nevertheless, the processes and root causes of vulnerability among fishers are different from one fishery to another (Adger et al., Citation2004). In the current study, the causes of vulnerability among fishers were firstly, lack of stakeholder support towards alternative livelihood strategies, secondly, lack of fisheries’ policy direction on the matter and thirdly, the increase in immigrant fishers.

Solving the problem of immigration was elusive in the current study at both local and national levels. There has been no enforcement of appropriate legislation and customary laws by local authorities and traditional leaders respectively to minimise the influx of immigrant fishers simply because everyone is considered a Zambian citizen with the liberty to settle anywhere. Njock & Westlund (Citation2008) argue that internal migration and the transboundary migration of fishers usually in search of better livelihoods and fish stock abundance is a global phenomenon. As such, the United Nations Development Programme through the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (UNDP, Citation2015) and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM, Citation2010) have been advocating the creation of migration policies and ratification of conventions and protocols by member countries in order to protect the rights and privileges of all migrants. The SDG 10 in particular focuses on facilitating responsible migration of people through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies. For Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery, this is one aspect in which stakeholders can engage the central government and the local government to adopt adequate policy interventions to increase the positive impacts and decrease the negative impacts of immigrant fishers on the resources of the fishery.

Furthermore, the majority of the fishers in this study showed apathy, not only to social asset-enhancing community groupings but also to the operations of their association (the FFTA). However, their apathy towards the FFTA was primarily due to the association’s weak local governance approach that prevented fishers’ participation and failed to meet the livelihood needs of the fishers. The study of Lundström & Nordlund (Citation2016) reveals that proper participation of local fishers in the co-management governance of fisheries resulted in positive socio-economic effects on the fishers of Ggaba, Uganda. A stronger local governance structure is, therefore, required for the Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery.

Despite the apathy, there was a cordial, social cohesion among the fishers in this study that enabled them to work together outside the FFTA and helped to mitigate the impact of vulnerability in their fishing businesses. Such cohesion indicates that there is a possibility for a healthy and inclusive governance structure through the FFTA to help address the challenge of vulnerability. The potential of such social cohesion in collaborative local governance was also highlighted by Nunan et al. (Citation2018) in her study on Lake Victoria fishing communities. Allison & Horemans (Citation2006) and Sulu et al. (Citation2015) also confirm that a reliable local governance approach in fishing-dependent fisheries is critical for attending to fishers’ vulnerability and livelihood assets.

4.3. Livelihood coping strategies of fishers and impact on livelihoods

Some fishers in the current study attempted various livelihood strategies beyond fishing as additional income sources, primarily crop and livestock production. However, there was little or no success in crop and livestock production due to drought, floods, expensive inputs, and livestock diseases. As such, the income levels and the livelihoods of the fishers were negatively affected.

Besides, the small town of Itezhi-Tezhi did not have many employment opportunities (DoF, Citation2014b). Béné (Citation2006) argues that the high dependence on fishing income by fishers may be because other employment options with higher returns are not available to them. Therefore, the level of unemployment in Itezhi-Tezhi district further explains the influx of people into fishing and fish trading around the fishery and the resultant negative impact on livelihoods.

Alternative livelihood strategies enable fishers’ households to become involved in different economic sectors, thus cushioning the effects of variations in fisheries’ resources (Charles, Citation2011). Involvement in alternative livelihood strategies seemed to be the way forward for the Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishers since fishing income was no longer dependable. However, support from the fishery's stakeholders towards such strategies was needed. This study revealed that the lack of stakeholders’ support was partly because fishers and the FFTA leadership were perceived to be too institutionally disorganised to warrant such support. As such, there is a need for fishers to cultivate stronger collaborations with other stakeholders in order to attract their expertise and resources and help boost alternative income sources as was demonstrated by small-scale fishers and the government on Lake Chiuta, Malawi (Donda, Citation2017).

5. Conclusion

Based on the Sustainable Livelihood Approach, the findings of this study revealed that the dynamic, small-scale Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery requires a holistic and multi-sectoral approach to address the livelihood needs and challenges of the fishers’ households and to achieve livelihood sustainability. To enhance the livelihoods of the households of small-scale fishers at Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery, this study suggests the following strategies: (a) support of fishery stakeholders towards alternative income sources; (b) development of a legally mandated local governance system to meet livelihood needs; (c) development or adoption of fisheries-related migration policies and strengthening of customary laws to minimise the negative impact of immigrant fishers; and (d) development of a livelihood-inclusive fisheries policy framework. The outcome of these strategies may also help to reduce pressure on the resources of the Lake Itezhi-Tezhi fishery and enhance the sustainable use of these resources.

Beyond Lake Itezhi-tezhi fishery, this study contributes lessons to the small-scale inland fishing and livelihoods debate. The study highlights the need for the development or enactment of the right livelihood-tailored fisheries policies and legislative frameworks that would compel the engagement and incorporation of appropriate stakeholders in fishers’ livelihoods and sustainable fishing, besides the government. These policies and legislative frameworks should be developed or revised and strictly adhered to by all stakeholders concerned.

A further study is needed that would assess and analyse the status of the existing governance approach for the small-scale fishery at Lake Itezhi-Tezhi and its fishing status in order to ascertain the level of fishers’ involvement in the governance of the fisheries resources. This study would contribute to the understanding of the governance of African small-scale inland fisheries in relation to sustainable fishing and livelihoods.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the doctoral thesis of the corresponding author. Our thanks go to all Lake Itezhi-Tezhi stakeholders for participating in the study. We also extend our thanks for financial support to the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) through the Norwegian Programme for Capacity Development in Higher Education and Research for Development (NORHED) project.

Disclosure statement

No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Notes

1 For this study: Fishers who migrated to this fishing community to stay there permanently or temporarily

2 For this study: Fishers who were born in this fishing community and have continued to stay there

3 A temporary place by the lake with shelters set by the fishers where they stay and conduct their fishing activities during the fishing season

4 A permanent residential area along the lake shore where the fishers reside as they conduct their fishing and other activities

References

- Adger, WN, Brooks, N, Bentham, G & Agnew, M, 2004. New indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research Technical Paper No. 7. University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK.

- Allison, EH & Ellis, F, 2001. The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy 25(5), 377–88. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(01)00023-9

- Allison, EH & Horemans, B, 2006. Putting the principles of the sustainable livelihoods approach into fisheries development policy and practice. Marine Policy 30(6), 757–66. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2006.02.001

- Alvi, HM, 2016. A Manual for selecting sampling techniques in research. Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper No. 70218. Munich Univesity, Germany.

- Babbie, E, & Mouton, J, 2001. The practice of social research. Oxford University Press Southern Africa Ltd, South Africa.

- Belhabib, D, Sumaila, UR & Pauly, D, 2015. Feeding the poor: contribution of West African fisheries to employment and food security. Ocean and Coastal Management 111, 72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.04.010

- Béné, C, Neiland, A, Jolley, T, Ovie, S, Sule, O, Ladu, B, Mandjimba K, Belal, E, Tiotsop, F, Baba, M, Dara, L, Zakara, A, & Quensiere, J, 2003. Inland fisheries poverty, and rural livelihoods in the Lake Chad Basin. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 38(1), 17–51. doi: 10.1177/002190960303800102

- Béné, C, 2003. When fishery rhymes with poverty: A first step beyond the old paradigm on poverty. World Development 31(6), 949–75. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00045-7

- Béné, C, 2006. Small-scale fisheries: assessing their contribution to rural livelihood in developing countries. FAO Fisheries Circular No. 1008. Rome.

- Béné, C, 2009. Are fisheries poor or vulnerable? Assessing economic vulnerability in small-scale fishing communities. Journal of Development Studies 45(6), 911–33. doi: 10.1080/00220380902807395

- Béné, C & Friend, RM, 2011. Poverty in small-scale fisheries: Old issue, new analysis. Progress in Development Studies 11(2), 119–144. doi: 10.1177/146499341001100203

- Béné, C & Heck, S, 2005. Fish and food security in Africa. NAGA. WorldFish Center Quarterly 28, 8–13.

- Béné, C, Emma, B, Baba, MO, Ovie, S, Raji, A, Malasha, I, Andi, MN & Russell, A, 2008. Governance, decentralisation, and co-management: lessons from Africa. In AL Shriver (Ed.), 14th IIFET Proceedings, July 22–25th (pp. 1–11).: Achieving a sustainable future: managing aquaculture, fishing, trade and development, Oregon, Nha Trang, Vietnam.

- Béné, C, Steel, E, Luadia, BK & Gordon, A, 2009. Fish as the “bank in the water” - Evidence from chronic-poor communities in Congo. Food Policy 34(3), 108–18. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.07.001

- Binet, T, Failler, P & Thorpe, A, 2012. Migration of Senegalese fishers: a case for a regional approach to management.”. Maritime Studies 11, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/2212-9790-11-1

- Bless, C, Higson-Smith, C & Sithole, SL, 2013. Fundamentals of social research methods: an African perspective. 5th ed. Juta and Company Ltd, Cape Town.

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G, Dudley, N, Jaeger, T, Lassen, B, Broome, NP, Phillips, A, & Sandwith, T, 2013. Governance of Protected Areas: From understanding to action. Gland, IUCN Best Practice Protected Area Guideline Series No. 20, Switzerland.

- Charles, A, 2011. Good practices in the governance of small-scale fisheries, with a focus on rights-based approaches. In R Chuenpagdee (Ed.), World small-scale fisheries contemporary visions. Delft. Eburon Academic Publishers, The Netherland. pp 285–98.

- Creswell, JW, 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. SAGE Publications, London, UK.

- CSO (Central Statistics Office), 2014. 2010 Census of population and housing - Southern Province Analytical Report, Central Statistics Office, Lusaka, Zambia.

- De Graaf, G, Bartley, DM, Valbo-Jorgensen, J & Marmulla, G, 2015. The scale of inland fisheries, can we do better? Alternative approaches for assessment. Fisheries Management and Ecology 22, 64–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2011.00844.x

- De Satgé, R, 2002. Learning about livelihoods: Insights from Southern Africa. Periperi Publication, South Africa.

- DFID (Department for International Development), 1999. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. http://www.livelihoodscentre.org/documents/20720/ (Accessed on 21 March 2017).

- DoF (Department of Fisheries), 2014a. 2013 Annual Report, Department of Fisheries, Chilanga, Zambia.

- DoF (Department of Fisheries), 2014b. Frame survey report on Lake Itezhi-tezhi, Department of Fisheries, Zambia, Itezhi-tezhi, Zambia

- DoF (Department of Fisheries), 2015. 2014 Fisheries Statistics Annual Report, Department of Fisheries, Chilanga, Zambia

- Donda, S, 2017. Who benefits from fisheries co-management? A case study in Lake Chiuta, Malawi. Marine Policy 80, 147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.10.018

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation), 2009. A Fishery manager’s guidebook. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, UK, Rome.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation), 2015. Voluntary guidelines for securing sustainable small-scale fisheries in the context of food security and poverty eradication. FAO, Rome.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation), 2016. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2016 - contributing to food security and nutrition for all. FAO, Rome.

- Ghosh, BN, 1992. Scientific method and social research (3rd edn). Sterling Publishers Pvt Ltd, New Delhi.

- Godet, F & Pfister, S, 2007. Case study on the Itezhi-tezhi and the Kafue Gorge Dam. The science and politics of international water management, SS 07. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich.

- Government of Zambia, 2011. The Fisheries Act of 2011, No. 22. Zambia. http://www.parliament.gov.zm/sites/default/files/documents/acts/The Fisheries Act%2C 2011.pdf. (Accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Haambiya, L, Kaunda, E, Likongwe, J, Kambewa, D & Muyangali, K, 2015. Local-scale governance: A review of the Zambian approach to fisheries management. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 5(2), 82–91.

- Harper, S, Grubb, C, Stiles, M, Sumaila, UR, Harper, S, Grubb, C & Sumaila, UR, 2017. Contributions by women to fisheries economies: Insights from five maritime countries. Coastal Management 45(2), 91–106. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2017.1278143

- Hauzer, M, Dearden, P & Murray, G, 2013. The fisherwomen of Ngazidja island, Comoros: fisheries livelihoods, impacts, and implications for management. Fisheries Research 140, 28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2012.12.001

- Huchzermeyer, CF, 2013. Fish and Fisheries of Bangweulu Wetlands, Zambia. MSc Thesis, Rhodes University, South Africa.

- IOM (International Organisation for Migration), 2010. Regional assessment on HIV-prevention needs of migrants and mobile populations in Southern Africa. IOM, Pretoria.

- Isaacs, M, 2012. Recent progress in understanding small-scale fisheries in Southern Africa. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 4(3), 338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2012.06.002

- Kadfak, A, 2019. More than just fishing: The formation of livelihood strategies in an urban fishing community in Mangaluru, India. Journal of Development Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1650168.

- Kébé, M & Muir, J, 2008. The sustainable livelihoods approach: New directions in West and Central African small-scale fisheries. In Achieving poverty reduction through responsible fisheries. Lessons from West and Central Africa. Part 2 (pp. 5–84).

- Kefi, AS & Mofya-Mukuka, R, 2015. The fisheries sector in Zambia : status, management, and challenges. Indaba Agriculture Policy Research Institute Technical Paper No. 3, Zambia.

- Kleiber, D, Harris, LM & Vincent, ACJ, 2015. Gender and small-scale fisheries: a case for counting women and beyond. Fish and Fisheries 16(4), 547–62. doi: 10.1111/faf.12075

- Kohn, LT, 1997. Methods in case study analysis. The Center for Studying Health System Change, Technical Publication No. 2. Washington DC.

- Lawrence, TJ, 2015. Investigating the challenges and successes of community participation in the fishery co-management program of Lake Victoria, East Africa. PhD Thesis. University of Michigan, USA.

- Levine, S, 2014. How to study livelihoods: Bringing a sustainable livelihoods framework to life. Working Paper 22, ODI, London, UK.

- Lundström, L & Nordlund, S, 2016. Exploring co-management: a minor field study on Lake Victoria Beach. BSc Thesis, Linköpings University, Sweden.

- Lynch, AJ, Cowx, IG, Fluet-chouinard, E, Glaser, SM, Phang, SC, Beard, TD, Bowerf, SD, Brooksf, JL, Bunnellg, DB, Claussenh, JE, Cookef, SJ, Kaoi, Y-C, Lorenzenj, K, Myersa, BJE, Reidf, AJ, Taylorf, JJ & Youni, S, 2017. Inland fisheries – Invisible but integral to the UN sustainable development agenda for ending poverty by 2030. Global Environmental Change 47, 167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.10.005

- May, C, Brown, G, Cooper, N, & Brill, L, 2009. The sustainable livelihoods handbook: an asset-based approach to poverty. UK: Church Action on Poverty/Oxfam GB.

- McClanahan, T, Allison, EH & Cinner, JE, 2015. Managing fisheries for human and food security. Fish and Fisheries 16(1), 78–103. doi: 10.1111/faf.12045

- McHugh, ML, 2013. The Chi-square test of independence lessons in biostatistics. Biochemia Medica 23(2), 143–9. doi: 10.11613/BM.2013.018

- Mills, D, Béné, C, Ovie, S, Tafida, A, Sinaba, F, Kodio, A, Russell, A, Andrew, N, Morand, P & Lemoalle, J, 2011. Vulnerability in the African small-scale fishing communities. Journal of International Development 23, 308–13. doi: 10.1002/jid.1638

- Neiland, AE, Madakan, SP & Béné, C, 2005a. Traditional management systems, poverty and change in the arid zone fisheries of Northern Nigeria. Journal of Agrarian Change 5(1), 117–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0366.2004.00096.x

- Neiland, EA, Chimatiro, S, Khalifa, U, Ladu, BMB & Nyeko, D, 2005b. Inland fisheries in Africa. NEAPD-Fish for All Summit.Technical Review Paper Abuja, Nigeria.

- Ngoma, PG, 2010. The welfare value of inland small-scale floodplain fisheries of the Zambezi River Basin. PhD Thesis, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

- Njock, J & Westlund, L, 2008. Understanding the mobility of fishing people and the challenge of migration to devolved fisheries management. In: Westlund, L, Holvoet, K, & Kébé, M. Achieving Poverty Reduction through Responsible Fisheries. Lessons from West and Central Africa. Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 513. FAO, Rome.

- Nunan, F, Cepić, D, Mbilingi, B, Odongkara, K, Yongo, E, Owili, M, Salehe, M, Mlahagwa, E & Onyango, P, 2018. Community cohesion: social and economic ties in the personal networks of fisherfolk. Society and Natural Resources 31(3), 306–19. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2017.1383547

- Nunan, F, Hara, M & Onyango, P, 2015. Institutions and co-management in East African inland and Malawi fisheries: A critical perspective. World Development 70, 203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.01.009

- Ogutu-Ohwayo, R & Balirwa, JS, 2006. Management challenges of freshwater fisheries in Africa. Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management 11(4), 215–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1770.2006.00312.x

- Onyango, PO, 2011. Occupation of last resort? small-scale fishing in Lake Victoria, Tanzania. In S Jentoft & A Eide (Eds.), Poverty mosaics: Realities and prospects in small-scale fisheries (pp. 97–124). Springer, Dordrecht.

- SADC (Southern Africa Development Community), 2016. The SADC protocol on fisheries: Focus on the Zambian fisheries Sector. SADC Fisheries Fact Sheet, Vol. 1., Botswana.

- Schram, AB, 2014. A mixed methods content analysis of the research literature in science education. International Journal of Science Education 36(15), 2619–2638. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2014.908328

- Scoones, I, 1998. Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. IDS Working Paper No.72. Institute of Development Studies, UK.

- Sheatsley, PB, 1983. Questionnaire Construction and Item Writing. In P. H. Rossi, J. D. Wright, & A. B. Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of Survey Research. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Shi, F, 2015. Study on a stratified sampling investigation method for resident travel and the sampling rate. Hindawi - Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society 2015, 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/496179

- Sililo, AM, 2016. Institutions and human mobility in an African river fishery: a case study of fishing camps on the Kafue Flats, Zambia. MSc Thesis, Monash University, South Africa.

- SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), 2008. SPSS regression 17.0. SPSS Incorporated, Chicago.

- Sulu, RJ, Eriksson, H, Schwarz, AM, Andrew, NL, Orirana, G, Sukulu, M, Oetal, J, Harohau1, DS, Sibiti, S, Toritela, A & Beare, D, 2015. Livelihoods and fisheries governance in a contemporary Pacific Island setting. PLoS ONE 10(11), 1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143516

- SWECO (Swedish Consultants), 1971. Kafue River Hydro-electric power development stage II Report. Sweden.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), 2015. Sustainable Development Goals. UN. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (Accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Weeratunge, N, Béné, C, Siriwardane, R, Charles, A, Johnson, D, Allison, EH, Nayak, PK & Badjeck, MC, 2014. Small-scale fisheries through the wellbeing lens. Fish and Fisheries 15(2), 255–79. doi: 10.1111/faf.12016

- Welcomme, RL, Cowx, IG, Coates, D, Béné, C, Funge-Smith, S, Halls, A & Lorenzen, K, 2010. Inland capture fisheries. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 365(1554), 2881–96. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0168

- Yuerlita, 2013. Livelihoods and fishing strategies of small-scale fishing households faced with resource decline: a case study of Singkarak Lake, West Sumatra, Indonesia. PhD Thesis. Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand.