ABSTRACT

This paper explores the ‘alternative’ empowerment roles of catalyst, facilitator and advocate in community-based tourism in the context of community development practice, drawing on findings from four community-based tourism (CBT) ethnographic case studies in Kenya. A ‘friend’ or ‘neighbour’ relationship is uncovered as a possible combination of these roles. The various roles may be points or positions in a continuum, a relationship that develops over time. The roles could be realised between a community and an individual from within or outside the community. It is further proposed that understanding the roles and the relationships provides possibilities for community empowerment and sustainable community development within CBT settings. The findings point towards opportunities for the enhancement of empowerment, either driven by deliberate efforts of development practitioners or brought about in non-deliberate, organic manner through collaborative work of a wide range of actors.

1. Introduction

Empowerment is a pervasive term and applied in many fields albeit it continues to be a controversial and contested construct (Page & Czuba, Citation1999). Nevertheless, ‘empowerment and community development are irrevocably connected’ (Toomey, Citation2011:183). Power has been used as means for evaluating community development in terms of its processes and outcomes (Craig, Citation2002; Corbett & Fikkertt, Citation2012). This paper is anchored on conceptions of power as shared or relational and consequently generative (Rappaport, Citation1987; Speer & Hughey, Citation1995; Toomey, Citation2011). This aspect of power has been captured in relation to feminism (Starhawk, Citation1987), grassroot organisations, ethnic groups (Nicola-McLaughlin & Chandler, Citation1984) and individuals in families. Further, the formulation of power is characterised by collaboration, sharing and mutuality or ‘power with’ and is defined as ‘the capacity to implement’ rather than to control and dominate, in a purely Weberian fashion (Kreisberg, Citation1992:57). It is within this understanding of power that the possibility of empowerment exists and is embraced as a change process.

Empowerment is then defined as a ‘multi-dimensional social process that helps people to gain control over their own lives. It is a process that fosters power (the capacity to implement) in people, for use in their own lives, their communities, and in their society, by acting on issues that they define as important’ (Page & Czuba, Citation1999:Section 3, para. 2). This definition attempts to describe power in a less restrictive manner and allows it to be understood in the context in which it is being applied. Seen this way, empowerment has three definitional components: it is multi-dimensional—social, psychological, economic; it is multi-level— with interconnectedness between the individual, group, community; and, a process that develops over time like a journey rather than a point in space and time.

The importance of a practice-based approach to empowerment relates outcomes to its diverse settings such as a family (Grant et al., Citation2015) and community-based (Kerrigan et al., Citation2015). This paper extends the discussion of empowerment through the examination of a relationship described as ‘friend’ or ‘neighbour’ encountered in emic accounts from four community-based tourism case settings in Kenya. The disclosed relationship seemingly combines notions of power and trust by demonstrating how power by powerful actor(s) identified here as friend or friends become a part of an empowerment process based on mutual trust between them and those empowered in a collaborative manner. The empowerment approach, therefore, brings together the notions of power and trust in a way that has hardly been articulated in community-based tourism. Organisationally, the remainder of this paper unfolds in terms of four further sections of material. These relate to an examination of power in community-based tourism, the importance of trust within the conceptual context, research methods and study context, and research findings.

2. Empowerment and community-based tourism

Notwithstanding criticisms about its shortcomings (Goodwin & Santilli, Citation2009), community-based tourism (CBT) has grown in importance across sub-Saharan Africa and embraced by many communities and governments for socio-economic well-being as well as environmental and cultural preservation (Lwoga, Citation2019). CBT is a contested concept and defined here as ‘tourism development within a particular community, which uses local resources and strives for equal power relations through community ownership and control in a way that achieves community-determined outcomes’ (Mayaka, Citation2015:15). Mayaka et al. (Citation2019) opine that an evolutionary trajectory of CBT has produced two alternative conceptualisations, one that seeks to involve community in traditional tourism planning (Murphy, Citation2012) and another whose aim is community development through tourism (Giampiccoli & Saayman, Citation2014). Which model is appropriate may be determined by the context. This paper aligns with the latter. In this conceptualisation, the exercise of power and control by a community is recognised as a vital element (Mayaka et al., Citation2018), with CBT seen as empowering to communities (Jamal et al., Citation2019).

The notion of community empowerment through tourism community-based development approaches attracts substantial academic attention (Akama, Citation1996; Scheyvens, Citation1999, Citation2000; Sofield, Citation2003; Panta & Thapa, Citation2018). A holistic concept of empowerment identifies its economic, social, psychological and political components (Scheyvens, Citation1999). The possibility of CBT ventures opening up empowerment opportunities for marginalised sections of society has been pursued (see Akama, Citation1996; Panta & Thapa, Citation2018), with a growth of such ventures observable since the 1980s (Scheyvens, Citation2000). We argue that, to a large extent, the dominant views in this sustainable tourism development and empowerment nexus have focused on determined strategic outcomes at a cost of neglecting important social processes. There is a need to examine empowerment as a process if (and when) it takes place in natural settings in a less deterministic manner (Mayaka et al., Citation2018). Empowerment can be applied as the theoretical lens to examine CBT development as social change (Lardier, Citation2018; Zimmerman et al., Citation2018). Overall, the need is to incorporate understanding of empowerment as a praxis encompassing generative and productive aspects of power rather than hegemonies (Kang, Lee, & Kim, 2017; Gök, 2020) (Kang et al., Citation2017; Gök, Citation2020). Since trust represents a critical aspect of the relationships between development organisations, or outside actors, and communities (Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2016) it is essential to explore further the importance of the concept.

3. Importance of trust in empowerment

The concept of trust is applied across a wide range of fields including tourism research (Nunkoo et al., Citation2012; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2012; Nunkoo, Citation2015; Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2016, Citation2017). Arguably, trust is an important lens through which relationships in community development settings can be analysed (Rousseau et al., Citation1998; Seligman, Citation2000; Weber & Carter, Citation2003). Further, as is observed in the context of community development research and practice, trust has the potential to ‘enhance learning … build relationships [and] allow dialogue between different actors’ (Lachapelle, Citation2008:54). The quality and level of trust can be a measure of community control as it affects and directs relationships within a community as well as between a community and outside players. That said, there are certain ambiguities in its usage (Arnott, Citation2007).

Trusting another party carries a degree of vulnerability or risk (Rousseau et al., Citation1998). The key characteristics of trust, therefore, include expectations, vulnerability or risk and perceptions. Seligman (Citation2000) points out that a relational view positions trust as an underlying condition that shapes how individuals act and interact with each other. Of relevance is the realm of close interpersonal relationships built upon friendship (Weber & Carter, Citation2003). Taking these views into account, trust is hereby defined as a state of being that accepts vulnerability based upon expectations of good intentions by another actor (Rousseau et al., Citation1998). Broadening the idea of trust, as opposed to relying on analyses of power relations and hegemonies, allows the interrogation of community development challenges in diverse settings (Lachapelle, Citation2008). Trust is used along with power to examine empowering relationships in Community-based Tourism Enterprise (CBTE) settings in four study sites. The analysis seeks to shed fresh light on empowerment and development in rural African settings through a process-based examination of the roles of empowering parties. In doing so, it adds to the current understanding of empowerment and challenges the application of less generative views of power. The caveat must be made that while it is not expected that the study findings will apply to all cases, they present alternative workable interpretations of the roles of community outsiders and community perspectives on power and trust relationships.

4. Method and Cases

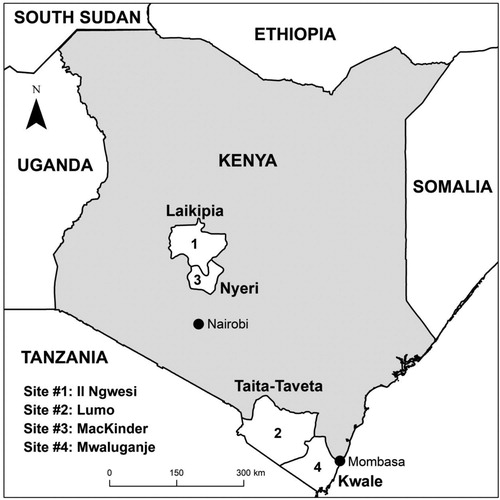

This paper reports emic descriptions of what is deemed an empowerment process emerging from an ethnographic study involving four community-based case studies in Kenya (), a country which has adopted a CBT strategy (Government of Kenya, Citation2013) and located in a region of Africa that is experiencing growth of CBT (van der Duim et al., Citation2015). The study included 50 in-depth semi-structured interviews, involving seven organisational members, two private investors and 41 community members, all of whom were connected to the creation of CBTEs. These participants were selected as key informants with direct, relevant knowledge of the process involved in the creation and operation of the CBTEs. They also represented a broad spread of ethnicities, roles and insider/outsider perspectives. Of the 41 community members, 12 were founders (referred to as founding members if part of a founding team) whilst nine were either current/past managers or leaders in the CBT boards. Most interviews were conducted in Kiswahili, the lingua franca. In addition to detailed interviews, the research involved participant (researcher) observation and the examination of relevant documents where available, to provide triangulation of findings. The cases were purposively selected for their likelihood to illuminate CBT issues under scrutiny in the primary research focus (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). The cases have a known reputation (Miles et al., Citation2014) within the CBT literature (Manyara & Jones, Citation2007). One case (Il Ngwesi), in particular, has a paradigmatic quality as it has potential to typify a CBTE (Dreyfus, Citation1987) and was selected in the field as participants from other cases made frequent reference to it (Creswell, Citation2013). The four cases display cultural diversity as they represent varying ethnic communities and regions in Kenya.

Case one is the 8,675 acres (3,511 hectares) Il Ngwesi lodge which is community-owned and managed and situated in Laikipia County in the semi-arid northern rangelands, a part of Kenya subject to extreme dry periods and drought. The Il Ngwesi Maasai community consists of over 700 households with a total population of 8,000 of which 3,000 live within the communal ranch. Eighty per cent of the land has been set aside by the community for wildlife conservation. For several hundred years this land has been occupied predominantly by the Maasai people and used mainly for cattle grazing since the Maasai lost areas of more fertile arable land during the colonial period (Northern Rangelands Trust, Citation2013). As is the case for many sub-Saharan communities, cattle symbolise wealth for the Maasai and represent a significant cultural element. The harsh conditions in Kenya’s north impose severe restrictions on the viability of cattle ranching. The Il Ngwesi Maasai were trapped in a cultural web of dependence on cattle in an area unsuited to cattle production.

Case two is Lumo Community Wildlife Sanctuary which is in a wildlife migration corridor in Taita Taveta County 377 km from Nairobi and 160 km from Mombasa (). Lumo is an acronym derived from the names of the three community ranches, Lualenyi, Mramba, and Oza. The area is made up of lowlands and hill country, extending from an altitude of 150 metres to the highest point of 1,800 metres. Lumo lies within the Tsavo ecosystem which hosts Kenya’s largest wildlife parks, Tsavo East National Park, 11 747 km2 in size, and Tsavo West, spanning 9,065 km2. The neighbouring Taita Hills Game Sanctuary is privately-owned. In 1948, the establishment of the Tsavo National Park displaced the Taita people, removing their access to farmland. A 1992 policy change encouraged community involvement and regarded as a critical moment that facilitated the establishment of the Lumo Wildlife Sanctuary (Akama & Kieti, Citation2007).

Case three is the Mackinder Eagle Owl Sanctuary a small CBTE at Kiawara village in Kenya’s Central Highlands. The sanctuary was the brainchild of a farmer Paul Muriithi who turned part of his land over to the preservation of an endangered owl species. The preservation of the owl ran contrary to his Kikuyu community’s beliefs that it represents a harbinger of death. Getting the community onside and altering traditional attitudes to the birds were vital for the success of his conservation plans. This attitudinal shift was affected in no small part by the creation of a tourism business and the sharing of profits/decision-making with the community.

Case study four is the Golini-Mwaluganje Community Wildlife Conservation Limited, commonly known as Mwaluganje Elephant Sanctuary, which is located in the impoverished Kwale County, 45 kilometres southwest of Mombasa. Together with the adjacent Shimba Hills National Reserve, a government-owned protected area, Mwaluganje is a part of what is known as the Shimba Hills ecosystem. Mwaluganje was established as a company in 1994. The company manages the sanctuary for the conservation and preservation of elephants. It is a CBTE consisting of land that local Digo and Duruma farmers donated to the project while delimiting their shareholding in the sanctuary which is registered as a company.

4.1. Coding and analysis

In keeping with contstructivist practices, codes were developed inductively from the cases. Following Miles et al. (Citation2014), a double-cycle schema was applied to capture the process of creation and development of the CBTEs. Within-case analysis included descriptive data emanating from the interviews, archival material from the all the four cases as well as observations made by the researcher. First-cycle coding holisticly assigned a single code to a ‘large unit of data in the corpus, rather than line-by-line coding’ (Miles et al., Citation2014:77). Such blocks of data have the potential to yield more than one second-level code. The aim of the first level analysis is to come up with a descriptive write-up of each case study in order to ‘become intimately familiar with each case as a stand-alone entity’ (Eisenhardt, Citation1989:540). As such, the coding produced the background to the cases as well as the other descriptive details that tell the CBTE creation and development story.

The second level consisted of interpretive codes that are the ideas, as analytically interpreted by the researcher based on the research question. The aim of second-cycle coding is to develop categories, themes or patterns from the first-level data to offer explanations and attempt to derive meaning therefrom. First and second level codes are contained in .

Table 1. First and second level coding

Being deeply qualitative this research is not intended to be broadly generalisable or directly replicable. The nature of ethnographic research means that the researcher’s own habitus necessarily influences the interpretation of results. The researcher and lead author is an ethnic African, born and raised in rural Kenya. One co-author is an ethnic Mzungu (European) also born in Kenya. But, whilst interpretations might be limited to a Kenyan perspective, we would argue that certain of the conclusions are applicable to other contexts, which would require further research either through additional case studies or rigorous quantitative studies.

5. Findings

The results highlight a thread of relationships between the communities and different individuals from outside the community playing different roles in the process of the establishment and development of the CBTEs. The search to develop better understanding of these relationships led us to Toomey’s (Citation2011) analysis of different actor roles within the community development practice context (). Toomey (Citation2011) styles empowerment as a complex web of interacting elements, including solidarity, respect, and propensity for collective action. She then outlines four ‘traditional’ empowerment roles, namely those of rescuer, provider, moderniser and liberator, as well as four non-traditional or ‘alternative’ roles, namely those of catalyst, facilitator, ally and advocate. The alternative-roles model provided a suitable framework for examination of the Kenyan findings.

Table 2. Empowering roles in community development: A process view.

Briefly explained, the catalyst shares new ideas and experiences in a horizontal learning situation but can also display a vertical relationship wherein the empowered and the empowering are in different levels of power (Vail, Citation2007). The facilitator role is characterised by a number of elements, including decision making, resource mobilisation, management, communication, coordination or even conflict resolution in a way that builds community capacity (Datta, Citation2007). The ally fulfils a helping role that shows compassion, respect and mutuality in a more or less horizontal relationship with the community and its members (Wallerstein & Duran, Citation2006). The advocate is similar to the ally in expressions of solidarity and support for individuals and communities. However, the advocate plays more of a politically active role. Advocates tend to be passionate supporters of struggles through involvement in social movements ‘as marchers’ (Toomey, Citation2011:192). The concept of trust appeared frequently in the emic accounts and so was included in the analysis.

The core findings reveal that many actors as agents of community development fit into multiple and overlapping alternative empowerment roles (catalyst, facilitator, ally and advocate) in the establishment and development of CBTEs. Although most come from outside the community, empowerment roles can be played by members from within the community itself. Moreover, the roles may apply in what would arguably be vertical and horizontal relationships. Some actors switch between roles at different stages of the development in a way that demonstrates relationships shaped by an interplay between power and trust. Admittedly, the accounts are based on the interview participants’ viewpoints and so should not be read uncritically. The following sub-sections examine the respective roles of catalyst, facilitator, ally and advocate, the actors who filled them, and the circumstances in which they did so.

5.1. Catalyst

In the case of Il Ngwesi, a neighbouring Mzungu, Ian Craig, shared his ideas with the community on how to start a tourism business based on his own Lewa Downs Ranch. The interviewees used the words ‘neighbour’ and ‘friend’ interchangeably when referring to Craig who encouraged the community to follow his example and create a tourism enterprise in order to generate ongoing income in the face of drought-related livestock losses. A severe drought in 1983/84 caused a disruption of normal life in the Il Ngwesi environments. The death of the livestock triggered a process of diversification of local socio-economic activities to include tourism as an addition to pastoralism. The circumstances of drought spawned discussions between Craig and the Il Ngwesi Maasai elders about setting aside some land (traditionally valued for its use as pasture) for conservation of wildlife as a tourism resource. Previously, tourism was alien to the traditions of the Il Ngwesi Maasai, and this marked a significant shift in Maasai self-image which is tied to cattle ownership. The interview data corroborate information in the Il Ngwesi Strategic Plan for 2010–2014.

Members of Il Ngwesi II Group Ranch entered into discussions with Ian Craig from neighbouring Lewa Downs [Lewa Conservancy] about setting aside some of their land for wildlife conservation and about tourist-related business ventures that could raise income for the community (Il Ngwesi, Citation2010).

You see, we had visited and had talked to more elders. You know in our customs an elder, of a certain age and calibre, cannot tell lies, and their word is respected. Of particular mention is Mzee Ole Ntuntu … So, we drew from the wisdom of this Mzee [elder] because he had applied the same wisdom and got results (Olonana, founding member).

We also went to Loitokitok and we went to Kimana, tumeelimika [we have been educated] about the protection of our animals (Chirau, founding member, Mwaluganje).

Overall, the Il Ngwesi and Mackinder cases are illustrative of the catalytic role in vertical as well as horizontal relationships. In addition, the importance of trust is demonstrated by the Il Ngwesi Maasai’s faith in Craig and Ole Ntuntu, both of whom could be viewed as powerful in etic terms (Manyara & Jones, Citation2007; Geheb & Mapedza, Citation2008).

5.2. Facilitator

The facilitator role is characterised by elements such as decision making, resource mobilisation, management, communication, coordination or even conflict resolution in a way that builds community capacity (Datta, Citation2007). Interviews with the founding members at Il Ngwesi, revealed how Ian Craig helped to build capacity by, among other things, facilitating visits to other communities. The shift to looking after wildlife alongside livestock farming was a major change for the predominantly pastoralist Il Ngwesi Maasai:

Nobody was concerned with wildlife as it belonged to KWS [Kenya Wildlife Service] and it wasn’t at all ours (Olonana, founding member).

Craig also facilitated partnerships with funders of the project. One founding member, drew a distinction between Craig and the partners in the creation of Il Ngwesi CBTE:

A while ago Il Ngwesi had partners. There was KWS in as far as the wildlife issues were concerned. Then there are neighbours such as Lewa, and it is from Lewa that we got many more partners and friends, because Lewa is well known (Olonana, founding member).

In the Lumo case, an official with African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), John Kiio, assumed a facilitator role by brokering relationships between the community and other organisations:

We went through AWF to get Community Development Trust Fund (CDTF) money, Kiio connected us (Mghanga, board member).

He had a particular love for Lumo community because at one time we suggested that he would be sitting on the board, and he would become one of the members of the board of trustees, and in fact we were thinking seriously of involving him. Unfortunately, it is during that time that he resigned from AWF (Mghanga, board member).

In the Mwaluganje case a similar facilitation role was observed in 1994 by a community outsider, Kamau, who was at the time Kwale District Warden. Kamau made a proposal for the formation the Golini-Mwaluganje Community Conservation Ltd (Mburu & Birner, Citation2007). Upon retirement from the KWS he was approached to become the first manager of the sanctuary. Community members referred to his contribution to the development of Mwaluganje in his time as the manager. This information was corroborated through a personal interview with Kamau himself. Kamau still has an interest in Mwaluganje despite declining approaches from the elders to return to take up a position as the sanctuary manager. Community members who participated in the interviews cited Kamau’s contribution in negotiating with partners along with his ‘exceptional work’ as a manager, which was evidenced by the record earnings in the period of 1997–2000 of Kshs1,500 (over US $16) per share. Nevertheless, in 2000–2001, members of the community decided to terminate his services as the manager:

Mr. Kamau is the one who negotiated with all these people [at] Eden Rock [and] KWS because he was a former warden here, senior warden. Things were running smoothly, but because of the community, they came one day and said they didn’t want this manager and this manager must go (Rai, founding member).

Now, where things went wrong on our part, we were asked now, can you manage, where you have reached can you take over the management of the project? There are some people who are hot-headed, as a matter of fact we had not really gotten there. We said we can now manage. There was a manager who was being paid by Eden. He was called Kamau (Rai, founding member).

A powerful actor also played a facilitation role at Mackinder in its earliest days of operation.

I received my first visitor after the [initial] four Canadians [bird watchers]; Sir Jeffrey James, the British High Commissioner to Kenya (Paul, founder).

5.3. Ally

The ally fulfils a friendship/supporter/helping role that shows compassion, respect and mutuality in a more or less horizontal relationship with the community and its members (Wallerstein & Duran, Citation2006). Ian Craig’s Il Ngwesi activities of sharing and exchange of ideas, as well as the support given to the community in getting partners, fit within this role. The same can be said of Kiio’s help to Lumo to secure funding, and Kamau’s role at Mwaluganje. Kamau, a former game warden who lived in the locality for over 17 years. While working with the KWS (a Mwaluganje partner organisation) he contributed to the project by making proposals for solutions to the human-wildlife conflict. As already noted, during 2001 he switched roles from being a senior warden with KWS to become manager of Mwaluganje out of a commitment to the CBT and community development. It is of particular note that Kamau continues to assist the project despite having been removed from his managerial position and having no ongoing, official relationship with the enterprise.

Up to today, people remember Kamau. He became a manager, he used to look for white people [tourists]. Even today if we call him, he can come. You must like someone who helps you. (Kidombo, founding member).

When the ambassador came to our home, my parents were shocked and knew my fortunes [had turned] (Paul, founder).

When I went to take a carving of an owl to the ambassador, we talked like brothers. I was not even harassed by security people (Paul, founder).

5.4. Advocate

The activities that may be associated with the advocate role were evidenced only in the two cases of Il Ngwesi and Lumo. At Il Ngwesi this is illustrated by Craig’s instigation of the community to act against certain exploitative business activities. Campsites operated by whites from outside the community employed a few local Maasai as manual, casual labourers. As a ‘friend’ Craig alerted the community members of group of Wazungu entrepreneurs.

One friend of ours came to us and told us, there are people, Wazungu, who come here and employ our people; they do camping (Ntimama, founding member).

Craig began to be at loggerheads with these Wazungu who do camping. The Wazungu started to talk to the people they employed. This mzee [referring to Craig] is starting to incite you against us.’ (Ole Tipis, founding member)

This friend told us, this is your money, you people don’t know. He said, find three wazee to take them to Narok to see a Group Ranch. (Ntimama, founding member).

Kiio’s commitment and passion for Lumo characterised the advocate role. One interviewee, (Evan) who in this context can be regarded as an outsider and observer in the events, noted the enthusiasm exhibited by Kiio, then a community-based enterprise expert with AWF.

I watched a guy called Paul Kiio from AWF dealing with big meetings, AGMs, government meetings, and he could really whip up the enthusiasm and he is very good at that. (Evan, investor).

6. Discussion

provides a summary of the different empowerment roles played by different actors in the four Kenya case studies. It discloses that Craig at Il Ngwesi, Kiio at Lumo, Kamau at Mwaluganje and both Paul and Sir Jeffrey in the case of Mackinder, assumed different empowerment roles, albeit with obvious overlaps in the development of the CBTEs. It is shown that some players can act in more than one capacity. Arguably, these roles can be considered as part of a continuum of a friendship relationship. This friend relationship and the nuances of its manifestation across the four cases are fulfilled by an individual rather than by an organisation. The individual may be an outsider or a member of the community who acts out of a commitment to the community (representing one end of the continuum) or a cause (representing the opposite pole).

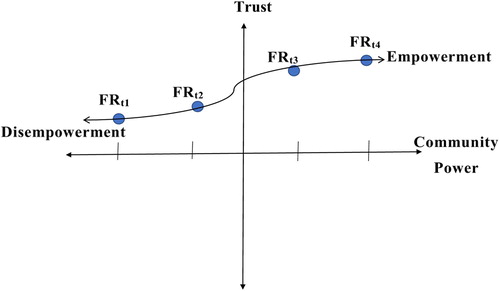

Two individuals, Craig (in the case of Il Ngwesi) and Kiio in the case of Lumo, extended their activities into the role of advocacy in the development of the CBTEs () Based on the findings it appears that the emic view of ‘friend’ or ‘neighbour’ explicitly used when referring to Craig connotes not just an empowerment role, but instead a more complex, lasting relationship. The roles may be visualised as points or positions along a continuum of friendship or neighbour relationships that evolve over time. It is possible to conceptualise and plot any of the CBTEs or initiatives at different points in time of the friendship relationship, which we argue is shaped by the interplay between power and trust. In turn, this means that the relationship has different effects in the community empowerment process. These are shown schematically in which reveals the empowerment roles of friend (FR) at different times (t1-t4) in the development of Il Ngwesi. As is evident, the actors may move between the roles at different stages of the development dependent on different combinations of trust and power. However, changes cannot be plotted strictly along a straight line. A movement of the relationship from catalyst and facilitator to ally and advocate roles can be seen as empowering. This explains the special relationship between Craig and Il Ngwesi as well as between Kiio and Lumo. Both actors were invited to join the respective boards of Il Ngwesi and Lumo as part of the communities. Such friendship relationships demand deeper investigation. Arguably, an authentic friendship relationship may be misinterpreted at some point in the earlier stages of development (FRt1 and FRt2) as disempowering because of the friend’s more prominent involvement as catalyst or facilitator (Manyara & Jones, Citation2007) Neverheless, over time these roles are replaced in prominence with ally and advocate (FRt3 and FRt4).

Figure 2. A plot of empowerment roles of friend (FR) at different times (t1−t4) of Il Ngwesi’s development. Source: Authors

Empowerment roles also have contradictions and challenges. For example, the late Ted Goss of Eden Wildlife Trust was a former warden in the area and partner who helped obtain initial funding for the Mwaluganje project. Although Goss is regarded by older members of the CBTE as a friend of the community a younger-generation, former chairman of the board, described him as mkoloni (colonialist).

The problem was there between the old men picked by Ted Goss. There was a system where young guys were saying that what he was doing was unfair (Nyae, founding member).

The examination of the multiple alternative empowerment roles, catalyst, facilitator, ally and advocate and their nuances highlights the utility of the empowerment concept in community-level sustainable tourism development. In particular, the concept of ‘friend’ or ‘neighbour’ uncovers the possibility of complex lasting relationships within communities as well as between communities and external actors. Such discussion has the potential of strengthening the interdependencies of conditions, groups and individuals and power in generative terms of what power can achieve. The ‘friend’ or ‘neighbour’ concept enriches the proposition for consideration of power alongside trust in CBT and sustainable tourism development (cf. Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2016).

Future research should explore further the friendship relationships including the lived world of such ‘friends’ and ‘neighbours’ and their views. Such an approach might enhance knowledge in the search for strategies to address developmental agendas such as poverty alleviation, sustainability and the necessary global partnerships to address them.

7. Conclusion

Although researchers such as Toomey (Citation2011) have identified specific roles of actors in the development and empowerment processes these are not clearly delineated in practice. Instead, there appear to be considerable overlaps between them. Moreover, actors can adopt more than one role in any given project. As we have argued, these roles are a part of a more complex friendship relationship. Friends might act in more of these overlapping functions. The friend relationship and the nuances of its manifestation across the four cases as uncovered by this research, is fulfilled by an individual rather than by organisations. This individual may be an outsider or a member of the community who acts out of a commitment to the community or a cause. The relationship may flow to the community at large (the Il Ngwesi case) or through one or more individuals within that community (in the Mackinder case). The friend ultimately acts to empower or advantage the community or individual and never to disempower. The friend might or might not be a ‘practitioner’. In the case of a mzungu, the friend role would appear to run contrary to that which might be predicted by a post – or neo-colonial analysis suggesting that such perspectives need to be applied in a more critical fashion. Indeed, nurturing friend relationships as uncovered in this study might prove vital for the success of community-based tourism development since the friend has no overt desire to wrestle control away from the community. The friend, therefore, can be a potent agent of community empowerment as well as a trusted catalyst of community development through enhancing agency and solidarity.

The paper contributes to theory with regard to productive aspects of power (Kang et al., Citation2017; Gök, Citation2020) and a practice-based approach of empowerment that allows the examinations of its outcomes in different contexts (Grant, Ballard, & Olson-Madden, Citation2015; Kerrigan, et al., Citation2015). The friend relationship in the Kenyan CBT cases demonstrates an empowerment process that combines role of powerful individuals and mutual trust and collaboration with community. In the final analysis this research advances the growing interest in the application of empowerment as a theoretical framework in the relationship between communities and tourism development in general and CBT in particular (Scheyvens, Citation1999; Boley et al., Citation2014; Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2016) and underlines the need for further scholarship around the role of power and trust in this context. In addition, the Kenya findings extend Sofield's (Citation2003) work on process aspects of empowerment. Additionally, they have relevance in relational community-based process oriented developmental approaches (Corbett & Fikkert, Citation2012). While the friend relationship in community empowerment in CBTE settings might be unique to Kenya, there is no reason to believe that it cannot exist in other sub-Saharan contexts and even beyond the African continent. Further research is needed to examine the relationship, particularly incorporating views and perspectives of the friends.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akama, JS, 1996. Western environmental values and nature-based tourism in Kenya. Tourism Management 17(8), 567–74.

- Akama, JS & Kieti, D, 2007. Tourism and socio-economic development in developing countries: A case study of Mombasa resort in Kenya. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(6), 735–48.

- Arnott, DC, 2007. Trust – current thinking and future research. European Journal of Marketing 41(9/10), 981–7.

- Boley, BB, McGehee, NG, Perdue, RR & Long, P, 2014. Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Annals of Tourism Research 49, 33–50.

- Corbett, S & Fikkert, B, 2012. When helping hurts: How to alleviate poverty without hurting the poor and yourself. Moody, Chicago.

- Craig, G, 2002. Towards the measurement of empowerment: the evaluation of community development. Community Development 33(1), 124–46.

- Creswell, JW, 2013. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 3rd edn. SAGE, London.

- Datta, D, 2007. Sustainability of community-based organizations of the rural poor: learning from Concerns rural development projects, Bangladesh. Community Development Journal 42(1), 47–62.

- Dreyfus, HL, 1987. Mind over machine: the power of human intuition and expertise in the era of the computer. IEEE Expert 2(2), 110–1.

- Eisenhardt, KM, 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14(4), 532–50.

- Eisenhardt, KM & Graebner, ME, 2007. Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. The Academy of Management Journal 50(1), 25–32.

- Geheb, K & Mapedza, E, 2008. The political ecologies of bright spots. In Bossio, D & Geheb, K (Eds.), Conserving land, protecting water, 51–68. CABI, Wallingford.

- Giampiccoli, A & Saayman, M, 2014. A conceptualisation of alternative forms of tourism in relation to community development. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(27), 1667–77.

- Gök, FA, 2020. ‘I wanted my child dead’ – Physical, social, cognitive, emotional and spiritual life stories of Turkish parents who give care to their children with schizophrenia: A qualitative analysis based on empowerment approach. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 66(3), 249–58.

- Goodwin, H & Santilli, R, 2009. Community-based tourism: A success? Leeds: ICRT Occasional Paper No. 11.

- Government of Kenya, 2013. National tourism strategy 2013–2018. Department of tourism, ministry of East Africa. Commerce and Tourism, Nairobi.

- Grant, C, Ballard, ED & Olson-Madden, JH, 2015. An empowerment approach to family caregiver involvement in suicide prevention: Implication for practice. The Family Journal: Counselling and Therapy for Couples and Families 23(3), 295–304.

- Il Ngwesi, 2010. Il Ngwesi group ranch strategic plan 2010–2014: Integrating community development and sustainable environmental management. Il Ngwesi, Nanyuki.

- Jamal, T, Budke, C & Barradas-Bribies, I, 2019. Community-based tourism and ‘development’. In Sharpley, R & Harrison, D (Eds.), A research agenda for tourism and development, 125–50. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK.

- Kang, YJ, Lee, JY & Kim, H-W, 2017. A psychological empowerment approach to online knowledge sharing. Computers in Human Behavior 74, 175–87.

- Kerrigan, D, Kennedy, CE, Morgan-Thomas, R, Reza-Paul, S, Mwangi, P & Win, KT, 2015. A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. Lancet 385, 172–85.

- Kreisberg, S, 1992. Transforming power: domination, empowerment, and education. State University of New York Press, Albany, NY.

- Lachapelle, P, 2008. A sense of ownership in community development: understanding the potential for participation in community planning efforts. Community Development 39(2), 52–9.

- Lardier, DT, Jr, 2018. An examination of ethnic identity as a mediator of the effects of community participation and neighbourhood sense of community on psychological empowerment among urban youth of colour. Journal of Community Psychology 46(5), 551–66.

- Lwoga, NB, 2019. International demand and motives for African community-based tourism. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 25(2), 408–28.

- Manyara, G & Jones, E, 2007. Community-based tourism enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 15(6), 628–44.

- Mayaka, MA, 2015. The role of entrepreneurship in community-based tourism. PhD. dissertation, Monash University, Melbourne.

- Mayaka, M, Croy, WG & Cox, JW, 2018. Participation as motif in community-based tourism: a practice perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26, 416–32.

- Mayaka, M, Croy, WG & Cox, JW, 2019. A dimensional approach to community-based tourism: Recognising and differentiating form and context. Annals of Tourism Research 74, 177–90.

- Mburu, J & Birner, R, 2007. Emergence, adoption, and implementation of collaborative wildlife management or wildlife partnerships in Kenya: a look at conditions for success. Society & Natural Resources 20(5), 379–95.

- Miles, MB, Huberman, AM & Saldana, J, 2014. Qualitative data analysis: A methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. SAGE, Los Angeles.

- Murphy, PE, 2012. Tourism: A community approach (Vol. 4). Routledge, Oxon.

- Nicola-McLaughlin, A & Chandler, Z, 1984. Urban politics in the higher education of black women: A case study. In Bookman, A & Morgen, S (Eds.), Women and the politics of empowerment, 180–201. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

- Northern Rangelands Trust, 2013. The story of the northern rangelands trust. Ascent, Nairobi.

- Nunkoo, R, 2015. Tourism development and trust in local government. Tourism Management 46, 623–34.

- Nunkoo, R & Gursoy, D, 2016. Rethinking the role of power and trust in tourism planning. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 25(4), 512–22.

- Nunkoo, R & Gursoy, D, 2017. Political trust and residents’ support for alternative and mass tourism: an improved structural model. Tourism Geographies 19(3), 318–39.

- Nunkoo, R & Ramkissoon, H, 2012. Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Annals of Tourism Research 39(2), 997–1023.

- Nunkoo, R, Ramkissoon, H & Gursoy, D, 2012. Public trust in tourism institutions. Annals of Tourism Research 39(3), 1538–64.

- Okech, RN, 2011. Ecotourism development and challenges: a Kenyan experience. Tourism Analysis 16(1), 19–30.

- ole Ndaskoi, N, 2005. The root causes of Maasai predicament. Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi) Paper 442. http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/442 Accessed 8 February 2018.

- Page, N & Czuba, CE, 1999. Empowerment: what is it? Journal of Extension 37(5), 1–5.

- Panta, SK & Thapa, B, 2018. Entrepreneurship and women's empowerment in gateway communities of Bardia National Park, Nepal. Journal of Ecotourism 17(1), 20–42.

- Rappaport, J, 1987. Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology 15(2), 121–48.

- Rousseau, DM, Sitkin, SB, Burt, RS & Camerer, C, 1998. Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review 23(3), 393–404.

- Scheyvens, R, 1999. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management 20(2), 245–9.

- Scheyvens, R, 2000. Promoting women’s empowerment through involvement in ecotourism: Experiences from the third world. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 8(3), 232–49.

- Seligman, AB, 2000. The problem of trust. Princeton University, Princeton.

- Sofield, TH, 2003. Empowerment for sustainable tourism development. Elsevier, Oxford.

- Speer, PW & Hughey, J, 1995. Community organizing: an ecological route to empowerment and power. American Journal of Community Psychology 23(5), 729–48.

- Starhawk, H, 1987. Truth or Dare. Harper & Row, San Francisco.

- Toomey, AH, 2011. Empowerment and disempowerment in community development practice: eight roles practitioners play. Community Development Journal 46(2), 181–95.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012. Il Ngwesi group ranch, Kenya. Equator initiative case study series. UNDP, New York.

- Vail, SE, 2007. Community development and sports participation. Journal of Sport Management 21, 571–96.

- van der Duim, R, Lamers, M & van Wijk, J, 2015. Novel institutional arrangements for tourism, conservation and development in eastern and Southern Africa. In van der Duim, R, Lamers, M & van Wijk, J (Eds.), Institutional arrangements for conservation, development and tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa, 1–16. Springer, New York.

- Wallerstein, NB & Duran, B, 2006. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice 7(3), 312–23.

- Weber, LR & Carter, AI, 2003. The social construction of trust. Plenum, New York.

- Zimmerman, MA, Eisman, AB, Reischl, TM, Morrel-Samuels, S, Stoddard, S, Miller, AL, Hutchinson, P, Franzen, S & Rupp, L, 2018. Youth empowerment solutions: evaluation of an after-school program to engage middle school students in community change. Health Education & Behaviour 45(1), 20–31.