ABSTRACT

In the Zambezi region, seemingly unrelated political visions propagate two development paths: nature conservation to promote tourism and Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM), and agricultural intensification. This study examines the unintended interrelations between these top-down visions by linking upgrading possibilities in agricultural value chains (AVC) with livelihood strategies of farmers from a bottom-up perspective. The results are based on qualitative field research that explains the how and why of the emergence of multiple rural development trajectories. We operationalise upgrading as actual and aspirational hanging in, stepping up and stepping out strategies. Findings show that although farmers envision stepping up their agricultural activities to better position themselves in AVCs, they remain in a strategic hanging in or downgrading state due CBNRM-related institutions. Concluding, we propose implications for CBNRM that synthesise competing development visions with actual livelihoods realities through the acknowledgment of small-scale agrarian systems rather than the crowding out of such.

1. Introduction

‘[The Zambezi] region, especially, has great potential to become the food basket and one of the tourism hubs in our country, and the government will work relentlessly to help make this reality’. (Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila, cited in Kooper, Citation2019).

Although the development of both agriculture and nature conservation is seemingly unrelated, their implementation on a common territory naturally results in interrelations. Large parts of Namibia are designated as national parks or conservancies; meanwhile 70% of the people depend on agriculture as the most important livelihood, and 23% on subsistence agriculture (Ruppel & Ruppel-Schlichting Citation2016). In the Zambezi region, there are 15 conservancies which cover 27% of the region’s surface. The region is relatively well-suited for agriculture with favourable climate and surrounding large rivers, but simultaneously shows increasing numbers of medium and large sized wildlife species (Mendelsohn Citation2006). As we show, the anticipated agricultural expansion is at odds with increasing efforts to establish communal conservancies across most of the region. Unlike the political narrative of two parallel paths, unintended and often detrimental interrelations exist and become evident when taking the perspective of local livelihoods.

Communal conservancies are a decentralised form of land-use and environmental management, which transfer authority to an organised committee, and offer the community opportunities to benefit primarily from tourism revenues (e.g. Bandyopadhyay et al. Citation2009; Lubilo & Hebinck Citation2019). Such Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) manifests in small, mosaic-like territories, where the institutional context significantly differs from institutions regulating communal land-use (Gargallo Citation2020). Due to the rapid expansion of CBNRM within the last three decades on the African continent, numerous studies concern the impact of conservancies on rural development (e.g. Anyolo Citation2012; Naidoo et al. Citation2019), the commodification of nature (e.g. Lenggenhager Citation2018; Koot Citation2019; Lubilo & Hebinck Citation2019; Kalvelage et al. Citation2020), and distribution of benefits within local communities (e.g. Bandyopadhyay et al. Citation2009; Silva & Mosimane Citation2014; Mosimane & Silva Citation2015; Schnegg & Kiaka Citation2018).

What is lacking in CBNRM-related research, however, is a multi-sectoral perspective that considers local residents’ livelihood strategies in response to top-down conservation efforts (Gargallo Citation2020). Moreover, little attention has been paid to differences among agricultural communities residing within and outside of conservancies. A comparative approach allows to filter out the impacts of CBNRM institutions on livelihood pathways. Against this backdrop, the paper investigates the impact of CBNRM visions and institutions on agricultural development and ultimately the livelihood strategies of small-scale farmers in the Zambezi region.

While we illustrate the changing livelihood strategies in agricultural value chains, this paper does not analyse the value chain per se, in its entirety from crop production to consumption. Rather, it focuses on the regional production segment and the prospects and limits of upgrading caused by interrelations with nature conservation by addressing the following questions: how do differing institutional settings, both in and outside of conservancies, shape farmers’ livelihood strategies? Which possibilities exist to upgrade their position within the regional agricultural value chain? The findings can contribute to a broader understanding of policy coherence and participation across localities in southern Africa, where nature conservation efforts often collide with people’s dependency on agricultural production and envisioned upgrading of agricultural value chains. Sections 2, 3, 4, and 5 present theoretical debates, methodology, empirical results, and policy implications respectively. We conclude by summarising our findings and reflecting on the need for further research.

2. Missing links in CBNRM research

In a recent reflection on both successes and failures of CBNRM, Koot et al. state that ‘CBNRM programs globally may fall short of their high expectations […]. Failures in terms of the gap between presented visions and the execution of these visions are observed as a feature of market-based dimensions of CBNRM’ (Citation2020:5). In other words, possibilities for households located in conservancies to generate income and establish sustainable livelihoods based on CBNRM are not sufficiently pronounced and diversified.

This missing link between vision and execution is especially relevant in the agrarian context (Gargallo Citation2020; Koot et al. Citation2020). Prior studies identify two major reasons for the disconnection between CBNRM benefits and agricultural livelihoods: as wildlife increases in protected areas, conflict with humans increases causing damage on agricultural infrastructure (Silva & Mosimane Citation2014; Schnegg & Kiaka Citation2018), and resource use for agricultural purposes such as water and land are restricted (Koot et al. Citation2020). By explicitly including agricultural value chains (AVC) in CBNRM studies, farmers’ livelihood strategies and upgrading possibilities can be associated to institutions brought about by communal conservancies. The subsequent sections set forth two concepts that help addressing the gap in CBNRM-related research: livelihood strategies and value chain upgrading.

2.1. The structural component of livelihood strategies

The livelihoods perspective (Scoones Citation1998, Citation2009) has recently been included in value chain studies to assess the impacts of our globalised economy from a structural, bottom-up perspective (Fold Citation2014; Vicol et al. Citation2019). We understand the term ‘livelihood’ as complex, diverse, and historically shaped pathways of pursuing life, either individually or within a household or community. The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) helps to conceptualise strategies that local actors choose to cope with their environment (Scoones Citation1998, Citation2009; Vicol et al. Citation2019). This paper does not aim to implement a ‘classic’ SLA which analyses each household’s physical, social, financial, natural and human capital. This approach has been critiqued by several researchers (e.g. Dorward Citation2009) for its instrumental conceptualisation of five capitals and for methodological individualism that underestimates the exploratory power of structures and institutions.

Rather than knowing which capitals are accessible, we argue that it is more important to provide reasons for specific capital endowments and resulting livelihood strategies. The institutional setting is crucial to depict reasons as to why certain strategies can or cannot be carried out. Institutions manifest in the form of laws, regulations and policies or local norms, values, and socio-economic regulations that shape livelihood aspirations and ultimately people’s agency to carry out certain actions. The institutional setting is simultaneously constituted by internal norms and values and externally implemented visions and regulations. In the case of CBNRM, novel institutions are for instance the establishment of a conservancy management board, the development of zonation maps to allocate land-use towards tourism, wildlife and agricultural areas and the management of income that is generated by the conservancy body (Mosimane & Silva Citation2015; Lenggenhager Citation2018). Thus, livelihood strategies are not developed individually and out of context; rather, they are shaped by structural conditions and institutional settings (Scoones et al. Citation2012; Vicol et al. Citation2018).

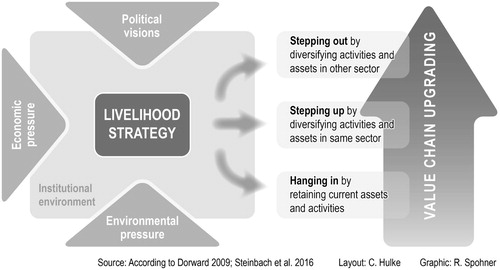

Dorward (Citation2009) usefully categorises livelihood strategies under the influence of various internal and external conditions through interrelations between livelihood strategies, their institutional environment and assets. Livelihood strategies are grouped according to three trajectories, referred to as hanging in, stepping up, and stepping out (Dorward Citation2009). These typologies have been applied in case studies on climate resilience, poverty, and small-scale farming (e.g. Dorward et al. Citation2009; Scoones et al. Citation2012; Steinbach et al. Citation2016; Vicol Citation2019; Yobe et al. Citation2019). Hanging in refers to households, often under precarious conditions that maintain their current activities without investment in new assets and thus do not upgrade their economic situation or position in the value chain. Stepping up entails efforts to upgrade current activities through investment in further assets, such as agricultural inputs or on-farm diversification. Stepping out refers to shifting to different activities that would deprive assets from their previous use for investment in new, more promising income generating activities, such as shifting from agricultural production to stable employment (Dorward et al. Citation2009; Dorward Citation2009; Vicol Citation2019).

To overcome the static nature of the SLA, livelihood strategies are therefore regarded as dynamic, aspirational trajectories that households do not always achieve, as they may drop out, move back or move up (Dorward Citation2009). ‘The possibilities of different households to hang in, step up, or step out (…) hinge on their location within the socio-political structure’ (Vicol et al. Citation2019:142), which becomes evident through conceptually linking development trajectories on the micro-level to structural and institutional dynamics.

2.2. Upgrading in agricultural value chains

In many rural areas in Africa, agriculture is an important livelihood and the main driver of economic development. Hinting towards the importance of upgrading in rural, agriculture-based contexts, Vicol et al. note that: ‘Value chain upgrading interventions have emerged in recent years as a dominant approach to rural development’ (Citation2018:26), and must be critically examined with regard to ‘livelihoods and local agrarian dynamics’ (Citation2018). Smallholder farmers, amongst other disadvantaged groups within value chains (e.g. female labourers in the Global South), have weaker positions in negotiating trade conditions or prices and thus less opportunities to capture value (Ponte & Ewert Citation2009). Therefore, questions of agency, power and benefit distribution of upgrading are recently gaining momentum in value chain research. Global Value Chain (GVC) approaches especially focus on firms’ upgrading strategies within the value chain – according to a ‘moving up the chain’ logic (Ponte Citation2019) – rather than impacts on and strategies of individual livelihoods (Vicol et al. Citation2018). Although we do not employ a GVC theory, we adapt the concept of upgrading in value chain-driven development to the livelihoods dimension in the following ways (e.g. Bair & Gereffi Citation2003; Barrientos et al. Citation2011; Barrientos et al. Citation2016; Lee et al. Citation2012; Vicol et al. Citation2018).

First, the basic understanding of the term ‘upgrading’ does not reflect horizontal hierarchies and unequal agency, such as the access to land or social networks within a chain. A multi-facetted use of the upgrading concept includes the acknowledgment of various upgrading trajectories, such as strategic downgrading, and asks for reasons not to ‘move up the chain’ (Ponte Citation2019; Ponte & Ewert Citation2009; Vicol et al. Citation2018).

Second, by moving past the firm-centric understanding of industrial economic upgrading through the four modes of process, products, functional, and inter-chain upgrading (Humphrey & Schmitz Citation2002; Ponte & Ewert Citation2009), scholars have increasingly included a social dimension to consider broader institutional structures that produce inequality and uneven power relations (Bolwig et al. Citation2010; Barrientos et al. Citation2011; Selwyn Citation2013). From a conceptual viewpoint, this paper applies an understanding of upgrading trajectories that may benefit smallholder farmers envisioned livelihoods. Hence, we consider the aspirational nature of either striving for stepping up or stepping out, as these indicate a desire for socio-economic upgrading. The critical question of who benefits from evolving value chains can be addressed through the conceptualisation of upgrading implications for livelihoods connected to chain segments, rather than by focusing on the chain as a whole. We therefore capture upgrading not solely through increases in agricultural income, but as the agency of farmers to carry out envisioned livelihood strategies. The acquisition of such agency can require an improved positionality within the value chain through know-how and social networks that does not lead to economic upgrading directly and measurably but causes relational improvement (Glückler & Panitz Citation2016; Krishnan Citation2017). summarises the conceptual framework of this study, linking livelihood strategies with dynamic upgrading in AVCs.

3. Methodology

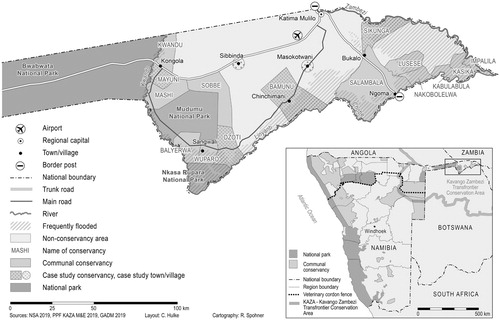

During field work in Zambezi region and the capital Windhoek from September to November 2018, we applied a qualitative, exploratory research design that employed three methodological approaches (). To identify reasons for developing livelihood strategies and aspirations connected with value chain upgrading, the core of this study was a bottom-up, participatory method based on focus-group discussions (FGD) and go-along interviews (GA) with farmers in selected case study conservancies and non-conservancy settlements. Institutional influences and political visions were captured through semi-structured interviews (I) with stakeholders from both the agricultural and conservation sector. The inter-sectoral perspective is used to differentiate the impact of visions for both conservation and agricultural intensification on local livelihoods. By considering delimited territories – communal conservancies and non-conservancies – we take direct influences of institutions on livelihood strategies into account.

Table 1. Conducted interviews by category from September until November 2018.

In Namibia, communal farmers are distinguished from commercial farmers by being non-title deed holders and title deed holders, respectively. This contribution focusses on small-scale communal farmers, characterised through small land parcels where mixed crops are grown, such as rain-fed staple crops (maize, pearl millet), other traditional crops (beans, ground nuts, leafy vegetables), or fruits and vegetables (horticulture products) (Mendelsohn Citation2006). Individual communal farmers typically cultivate land parcels less than 5 ha in size (according to Mendelsohn (Citation2006), the average size of cultivated land in Zambezi region amounts to 1.6 ha).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in Windhoek and in Katima Mulilo, the capital of the Zambezi region, with stakeholders from national and regional government bodies, non-governmental-organisations (NGOs) and the private sector (consulting, lobbying, associations). These interviews, conducted in English, were recorded and later transcribed. To address the bottom-up perspective, FGDs were held with communal farmers in six case study areas: four conservancies (Sikunga, Bamunu, Dzoti, Mayuni) and two non-conservancy settlements (Sibbinda, Masokotwani, ) as a comparison group. Sikunga conservancy was chosen because it is the only locality where conservation directly overlaps with the regions’ only Green Scheme (commercial irrigation scheme) for agricultural intensification. The other three conservancies offered heterogeneous insights through their varied population sizes, age structures, income sources, and locations. The two comparison settlements located in proximity to the conservancies allowed for comparisons based not on geographical location but rather on institutional frameworks ().

The FGDs were conducted in the local languages, mainly Silozi. Permission for recording was obtained and anonymity and confidentiality is maintained. The sampling of the FGDs was undertaken via local gate keepers, according to the following criteria: balanced numbers of male and female farmers, range of ages, crops produced, and field sizes. The total number of participants was 155 (F = 73, M = 82), the group size ranged from 5 to 20, with a mean of 9. One co-researcher guided the discussion in the local language according to a structured interview guideline, while a second research assistant offered ad hoc translation to enable the researcher to intervene when necessary. The FGDs were recorded, translated, and transcribed by the research assistants. Through their participatory, interactive nature, FGDs generate more reflective and layered insights on research topics compared to one-on-one interviewing. Ideally, social control mechanisms within the rounds of discussion and a more diversified range of opinions contribute to a solid database (Onwuegbuzie et al. Citation2009).

Go-along interviews with successful farmers identified in the FGDs functioned as micro case studies. As a qualitative approach, the go-along employed elements from ethnography by combining interviewing with participant observation in everyday life practices. Through the joint observation and mutual activity, the strict question-answer settings are broken up and an atmosphere was created that better reflected the interviewee’s reality (Kusenbach Citation2003).

The material was analysed using qualitative content analysis according to Mayring (Citation2000), applying structured deductive category application with the coding software MaxQDA. The coding categories reflect the guideline for the FGD, which was structured according to: livelihood wellbeing; AVC trajectory/farming activities; constraints; potentials; actors involved (associations, private businesses, governmental actors, NGOs, conservancy); future plans/aspirations.

4. Evidence from agricultural value chains in conservation areas in the Zambezi region

In the following, we first elaborate on the predominance of top-down visions and institutions related to CBNRM that impact the agricultural value chain and then uncover the corresponding impacts on livelihood strategies within and outside of conservancies in Zambezi.

4.1. Top-down visions and institutions of CBNRM

The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) and several NGOs supporting nature conservation create local institutions that predominantly shape development in conservancies. These conservation endeavours go back to the 1990s, following Namibia’s independence from South Africa. On the one hand, safari and hunting tourism has heavily benefitted from the growing number of conservancies and has managed to capture a substantial share of international value (Kalvelage et al. Citation2020). On the other hand, the change of land-use gradually caused a ‘crowding out’ of agricultural activities within conservancies (Gargallo Citation2020). Differing institutional frameworks and processes of commodification of natural resources, both within and outside of conservancies, as we argue, cause different possibilities for participating in AVCs and value chain upgrading.

Although conservancies aim at benefitting their members by generating income through natural resource use and tourism, farmers within conservancies complain about various constraints on agricultural production that can be linked to top-down conservation initiatives favouring tourism. Land-use restriction manifested in conservancy zoning plans, in particular, severely affect farmers, especially in accessing crucial inputs such as water. Conservancies are obliged to develop zoning maps, which define core wildlife areas, hunting areas, tourism areas, and settlement/cropping areas (NACSO Citation2017). Based on our findings, the dangers for power abuse with respect to land allocation, causes insecurities for farmers:

The conservancy management lied to us, they told us we would be able to plough and live with wild animals. The conservancy is paying little compared to the income I was going to get if I had harvested my crops. (FGD2-Bamunu-M)

Around here most of the fertile land is next to river and we cannot settle there anymore because it has become a core area for wildlife in this conservancy. (FGD2-Mayuni-F)

Table 2. Top-down visions of CBNRM, derived from FGDs and stakeholder interviews.

summarises the amount of income generated in the case study conservancies in 2017, including the source of income and the distribution of benefits, according to financial data gathered by the Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organizations (NACSO). The uneven distribution becomes evident when firstly looking at differences in the share of benefits, which are distributed among the members between the four conservancies. In Bamunu and Mayuni, roughly a quarter of the income generated is used for benefits, whereas Sikunga only distributes about 4% of its income to members. Second, how money is spent plays a major role in members’ satisfaction with the conservancy management. Corruption of conservancy management bodies in the process of income distribution is mentioned as a constraint of development within conservancies. Therefore, some communities are hesitant to establish a conservancy: ‘Having a conservancy doesn’t guarantee that the resources or benefits will be for the community. The community is just like a shepherd looking after those animals but, the larger shares go to the hands of the “mafias”’ (FGD2-Sibbinda-M).

Table 3. Accumulated income of case study conservancies and income distribution in 2017. Own calculations, based on NACSO (Citation2017).

A proclaimed goal of conservancies is the harmonious co-existence of humans and wildlife. To counteract impacts of increased Human-Wildlife-Conflicts (HWC), such as destruction of fields, attacks on cattle, or even humans, the conservancy compensates losses caused by wildlife through HWC offsets. Those payments are a crucial instrument to achieve legitimacy of conservation in agrarian contexts, and to increase satisfaction and support among farmers who suffer losses by virtue of their location within conservancies. Only Bamunu and Dzoti invested in HWC offsets, as shown in . Nonetheless, these measures are not sufficient to compensate losses and disadvantages associated with living and farming near wildlife (FGD2-Bamunu; FGD2-Mayuni). Finally, the income in all four conservancies is almost exclusively generated through hunting and other tourism, showing that conservancies largely depend on the tourism sector.

Farmers in conservancies state that there is a lack of support for agriculture (FGD1-Bamunu; FGD2-Sikunga). One reason is the administrative affiliation of territories gazetted as conservancies. They are under the umbrella of the MEFT, supported by NGOs, which give nature conservation priority over agricultural development (I_Gov5; I_NGO3; I_NGO4).

summarises the effect mechanisms identified in the implementation of top-down policies and visions both within and outside of conservancies. In the following subsection, we address how these mechanisms affect livelihood strategies and thus possibilities for upgrading.

Table 4. Generalised effect mechanisms of small-scale agriculture, derived from FGDs, go-along interviews and stakeholder interviews.

4.2. Impacts on livelihood strategies

Within conservancies, constraints in AVC upgrading and thus stepping up strategies occur especially in the production and marketing segments (). In the production segment, accessing inputs is the main limiting factor (FGD-Bamunu/Dzoti/Sikunga/Mayuni). The management zoning plans resulted in relocations of farmers from their previous crop lands when these were located near water bodies or forests. These areas are potentially suitable for irrigated agriculture but are also best suited for tourism (FGD1-Mayuni; FGD2-Sikunga). The increased HWCs have caused losses in yields (FGD-Dzoti/Mayuni). Therefore, AVC upgrading through stepping up – invest in agricultural activities and diversification – is barely visible. This prohibits farmers within conservancies to upgrade their positionality in supply channels and formalised value chains and puts them in a (perceived) position of comparative disadvantage compared to farmers outside of conservancies.

Table 5. Expressions of bottom-up perceptions on possible livelihood strategies, derived from FGDs.

The geographical reach of AVCs within conservancies is mostly restricted to neighbouring villages. The marketing segment is thus limited to selling occasional surplus on local markets with low value added. Agricultural inputs, such as chemical pesticides or herbicides, are not accessible as there is simply no market in the rural areas and insufficient financial capital. Therefore, only organic fertiliser (manure) is used on the fields (GA_Con1/2).

The quality differs, imported crops have high quality because they use fertilisers, us local farmers cannot afford to buy fertilisers and hybrid seeds because they are expensive but when we sell, we sell at a cheaper price. (FGD1-Bamunu-F)

The strategy of stepping out of agriculture is rarely mentioned. The few non-agricultural income-generating activities include employment in tourism enterprises or conservancy management boards (e.g. as cleaning staff, ranger, area representatives), or small vendors/services (e.g. hair braiding, sewing, selling sweets). However, permanent jobs are rare, resulting in dependency on crop farming: ‘For us, farming is everything we have, that’s how we maintain our livelihoods’ (FGD1-Mayuni-M). But apart from farming for reasons of necessity, farming is also seen as an important part of local culture and tradition that has been passed on for generations (FGD-Dzoti/Sibbinda). This cultural dynamic helps to explain the predominating aspiration for stepping up through AVC upgrading rather than stepping out altogether.

The presence of poor farmers in rural areas of the region depending on agriculture is a fact that the regional government is well aware of:

Of course, we have the small-scale farmers if we were going to go in the tourism way, will they be benefiting from it? Would there be food security from their side? Obviously, the answer is no. (…) Therefore, the two must run parallel, so we must have tourism on one side and agricultural production on the other side. But if you say forget about agricultural production, we must just have tourism alone – that would be a tragedy for the poor. (I_Gov4)

By contrast, farmers in non-conservancy areas express more freedom to choose the locations for their agricultural activities, as land is not allocated to certain uses, as in conservancies’ zoning. Contact to regional lead actors (local supermarket and an association for farmers), which are mostly located in Katima Mulilo, the only urban centre in the region, is crucial for developing successful stepping up strategies.

Whenever opportunities of stepping up arise, farmers would indeed dynamically adjust their livelihood strategy, e.g. changing from traditional rain fed crops to horticulture, establishing irrigation systems to increase productivity, or negotiate verbal contracts with buyers such as supermarkets (GA_NonCon1). Stepping up strategies that continue with existing practices of diversification of crops towards horticulture production was mentioned to be most successful.

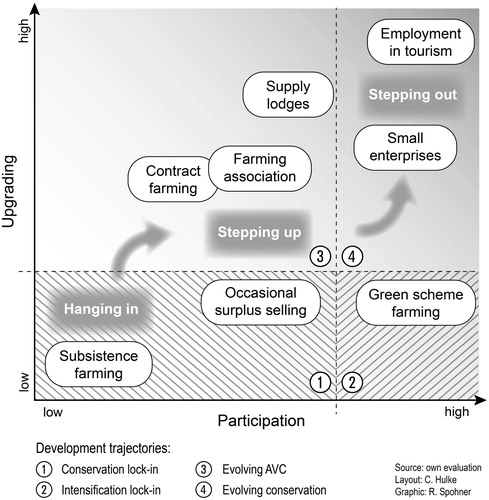

5. Development trajectories and resulting policy implications

Based on our findings presented above, we sketch out four development trajectories that are related to the various strategies and derive how the pursuit of envisioned strategies can be better supported by government initiatives. illustrates examples of how livelihood strategies of hanging in, stepping up and stepping out are carried out in the case study region and how these can be linked to value chain participation and upgrading: first, a conservation lock-in which contains hanging in due to locational constrains of being in a conservancy; second, an intensification lock-in, meaning hanging in through integration into a Green Scheme, which was only described by two farmers in Sikunga conservancy; third, evolving AVC which entails stepping up aspirations towards diversifying agricultural production and using assets to improve activities; and fourth evolved conservation, stepping out through the rare scenario of leaving agriculture and finding stable employment in the tourism sector.

However, a recent study by Kalvelage et al. (Citation2020), estimates the employment of tourism in Zambezi conservancies at 566 jobs. This represents a marginal share of 1.4% of the total labour force of 41 600 people in the region (NSA Citation2019). The tourism sector’s capacity is thus very limited to reduce the dependency on agriculture (see also Gargallo Citation2020). The political goals of providing alternative income sources through tourism and conservation in order to decrease dependency on crop production in conservancies – as is also the case with intensification measures through Green Schemes – have not sufficiently materialised on the ground.

Although livelihood strategies mostly aim at upgrading related to the AVC, e.g. through contract farming to supply lodges or collective action in associations, livelihoods within conservancies – due to several constraints outlined above – remain oriented towards subsistence farming and local surplus-selling. Regardless the support of market-based CBNRM initiatives, agriculture-based livelihoods are still dominant. Therefore, strengthening AVCs within conservancies is necessary.

Scholars agree that conservation is a significant constraint for agricultural development (Nyambe & Belete Citation2018; Gargallo Citation2020). This study provides an explanation for the exclusionary effects: commercial agriculture that would allow farmers to integrate into regional AVCs and lead towards relational upgrading is merely possible due to land insecurities, restricted water access and HWC. The resulting strategies of hanging in are not addressed by CBNRM initiatives, they rather create institutions that hinder rural development in the Zambezi region and can therefore be described as ‘a placebo type of relief to the unsustainable livelihoods’ (Nyambe & Belete Citation2018:2). The slowly emerging research on the importance of agricultural livelihoods within conservancies pinpoint towards a crucial reason for the rise of critical voices that contradict the predominantly positive narrative of CBNRM as an empowerment tool of rural communities (e.g. Lenggenhager Citation2018).

On the one hand, farmers within and outside of conservancies target a stepping up strategy, which is also envisioned by agricultural policies. On the other hand, these aspirations could, to a large extent, not be put into practice, as the production and marketing segments in AVCs are limited within conservancies. The fact that the larger share of farmers within conservancies does not directly participate in its benefit sharing schemes () and can therefore neither step up nor step out, confirms that development interventions through upgrading are ‘necessarily exclusionary’ (Vicol et al. Citation2018:35). Therefore, top-down initiatives need to acknowledge and include various forms of agricultural activities as livelihood strategies in multi-sectoral and participatory implementation schemes.

Moreover, land-use restrictions and HWCs disconnect farmers from elaborated AVCs, production intensification, and food security, contradicting the government’s vision of increasing domestic food production and commercialising smallholders. This finding, however, is consistent with development goals propagated by the MEFT or conservation NGOs that exclude agricultural development because it contradicts land-use requirements for nature conservation (). This calls for harmonising top-down visions with local realities and livelihood needs through cooperation between stakeholders in both sectors to establish a coherent, participatory policy-making that integrates various sectors and development trajectories.

Finally, we characterise decision-making of communal farmers as a logical, strategic response to exogenous influences and frictions in policy-making that limit their scope of action. The seemingly passive notion of hanging in can rather be seen as a strategic assessment – or strategic downgrading – of the situation based on experience and a limitation of farming activities adapted to the unstable institutional environment. Vicol et al. (Citation2018) point to the fact that farm households do not always follow neoclassical economic principles such as profit maximisation, which helps to make sense of the resistance that many farmers in conservancies have to stepping out of agricultural activities. Hence, the economic dimension of upgrading is not necessarily prioritised by farmers compared to a cultural and social dimension (Barrientos et al. Citation2011).

Moreover, as argued by Hazell et al. (Citation2010), due to changing political agendas and unpredictable dynamics in emerging economies, farming trajectories seldom pronounced as a linear path of growing and expanding, but rather remain a small-scale structure, which our results clearly show. The answer may be an alternative paradigm in agriculture to remain ‘small’, meaning to retain a small-scale structure and remain autonomous (Dorward Citation2009). This would, in turn, need an incremental institutional change in order to support participation and representation of smallholders endogenously, e.g. through collective action, to overcome dependency on international donors and trade imports (Andersson & Gabrielsson Citation2012; Dorward Citation2009; Naziri et al. Citation2014).

For this study, the ways that the four dominating development trajectories are interlinked, indicates that stepping up strategies are not automatically achieved through value chain upgrading; nor are stepping out strategies possible via the mere existence of alternative income sources, such as tourism in conservancies. It is more a question of agency and participation in the implementation of political visions that can lead to evolved positions within AVCs and inclusive, beneficial CBNRM institutions.

6. Summary and conclusion

Coming back to the Prime Minister’s statement on the promising development of both agriculture and tourism in the Zambezi region, the current nexus of initiatives and local strategies does not indicate the realisation of this vision.

Identifying interrelations between the two main development pathways, which mostly worsen the positionality of farmers within AVCs, contributed to a nuanced understanding of the reasons for failure in the implementation of political visions. The study has shown that up until now, the broader development implications of CBNRM visions and the contradictory goals of intensifying agriculture and expanding value chains, have not materialised in the Zambezi region. These unintended links between both sectors could be uncovered through the lens of aspired and achieved livelihood upgrading or downgrading.

Summarising, the findings revealed that farmers do aim at stepping up their livelihoods through intensification of agricultural produce, diversification of crops, or additional off-farm businesses. Subsistence farming for food security coupled with strategic surplus-selling on local or regional markets was identified as a predominant livelihood strategy. Although most farmers did envision stepping up strategies, upgrading their farming activities or diversifying was seldom possible. The results have shown that the two paths must be considered as intertwined rather than disconnected in order to harmonise the demands on resources by a variety of actors that come together in conservancy spaces (tourists, farmers, conservationists, flora and fauna, traders etc.). Otherwise, the high political expectations will not become reality.

Future policies could support existing local networks following a place-based approach. Here, the potential of collective action, contract farming, and backward and forward linkages for input access and marketisation needs to be explored further (e.g. Fold & Neilson Citation2016). As opportunities to step out of agriculture are limited in the case study region, a policy aiming at ‘accumulation from below’ (Aliber & Hall Citation2012) could strengthen local or regional AVCs without preventing farmers from pursuing farming, which is a major cultural and identity-forming activity.

Concluding, it must be recognised that CBNRM is a prominent and promising development tool in many countries in southern Africa. The framework and outcome of this analysis can be relevant for academia and practitioners beyond the borders of Namibia as it stresses the importance of integrating local resident’s perspectives and other, interrelated economic sectors. While this study’s complex, multi-layered actor setting shows certain patterns influencing livelihood strategies, the findings are not representative beyond the Zambezi region. The bottom-up approach considering aspirations of local actors, and contrasting those with top-down policies, initiatives and visions is necessarily subjective. Hence, we captured the perspective of farmers who feel disconnected from top-down intensification and conservation attempts and examined reasons for their discontent. Acknowledging the importance of space-specific local institutional settings and historical preconditions more empirical examples are needed on non-firm actors and horizontal – social and spatial – dynamics in other regions of sub-Saharan Africa which are shaped by nature conservation to identify beneficial development strategies associated with such top-down interventions.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted under the umbrella of the DFG-funded CRC TRR 228/1 ‘Future Rural Africa’. The corresponding author would like to thank collaborators at the University of Namibia, Katima Mulilo Campus. The research would not have been possible without the enormous support of our co-researcher and research assistant, Image Katangu and Pauline Munyindei (UNAM). The corresponding author would like to thank all the farmers and other research participants for openly sharing their knowledge. Two anonymous reviewers have contributed to final version of the paper and have improved it with constructive comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aliber, M & Hall, R, 2012. Support for smallholder farmers in South Africa: Challenges of scale and strategy. Development Southern Africa 29(4), 548–62. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2012.715441

- Andersson, E & Gabrielsson, S, 2012. ‘Because of poverty, we had to come together’: collective action for improved food security in rural Kenya and Uganda. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 10(3), 245–62. doi:10.1080/14735903.2012.666029

- Anyolo, PN, 2012. Conservancies in Namibia: Tools for sustainable development. In Hinz, MO, Ruppel, OC & Mapaure, C (Eds.), Knowledge lives in the lake: case studies in environmental and customary law from Southern Africa, 29–40. Namibia Scientific Society, Windhoek.

- Bair, J & Gereffi, G, 2003. Upgrading, uneven development, and jobs in the North American apparel industry. Global Networks 3(2), 143–69. doi:10.1111/1471-0374.00054

- Bandyopadhyay, S, Humavindu, M, Shyamsundar, P & Wang, L, 2009. Benefits to local communities from community conservancies in Namibia: An assessment. Development Southern Africa 26(5), 733–54. doi:10.1080/03768350903303324

- Barrientos, S, Gereffi, G & Pickles, J, 2016. New dynamics of upgrading in global value chains: shifting terrain for suppliers and workers in the global south. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48(7), 1214–19. doi:10.1177/0308518X16634160

- Barrientos, SW, Gereffi, G & Rossi, A, 2011. Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: A new paradigm for a changing world. International Labour Review 150(3-4), 319–40. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2011.00119.x

- Bolwig, S, Ponte, S, Du Toit, A, Riisgaard, L & Halberg, N, 2010. Integrating poverty and environmental concerns into value-chain analysis: A conceptual framework. Development Policy Review 28(2), 173–94. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00480.x

- Dorward, A, 2009. Integrating contested aspirations, processes and policy: development as hanging in, stepping up and stepping out. Development Policy Review 27(2), 131–46. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00439.x

- Dorward, A, Anderson, S, Bernal, YN, Vera, ES, Rushton, J, Pattison, J & Paz, R, 2009. Hanging in, stepping up and stepping out: livelihood aspirations and strategies of the poor. Development in Practice 19(2), 240–7. doi:10.1080/09614520802689535

- Fold, N, 2014. Value chain dynamics, settlement trajectories and regional development. Regional Studies 48(5), 778–90. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.901498

- Fold, N & Neilson, J, 2016. Sustaining supplies in smallholder-dominated value chains. In Squicciarini, MP & Swinnen, JFM (Eds.), The economics of chocolate, 195–212. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Gargallo, E, 2020. Community conservation and land use in Namibia: visions, expectations and realities. Journal of Southern African Studies, 1–19. doi:10.1080/03057070.2020.1705617

- Glückler, J & Panitz, R, 2016. Relational upgrading in global value networks. Journal of Economic Geography 16(6), 1161–85. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbw033

- Hazell, P, Poulton, C, Wiggins, S & Dorward, A, 2010. The future of small farms: trajectories and policy priorities. World Development 38(10), 1349–61. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.012

- Humphrey, J & Schmitz, H, 2002. How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies 36(9), 1017–27. doi:10.1080/0034340022000022198

- Kalvelage, L, Revilla Diez, J & Bollig, M, 2020. How much remains? local value capture from tourism in Zambezi, Namibia. Tourism Geographies 145(4), 1–22. doi:10.1080/14616688.2020.1786154

- Kooper, L, 2019, July 27. Thousands at Masubia cultural festival in Zambezi. The Namibian online. https://www.namibian.com.na/191256/archive-read/Thousands-at-Masubia-cultural-festival-in-Zambezi.

- Koot, S, 2019. The limits of economic benefits: Adding social affordances to the analysis of trophy hunting of the Khwe and Ju/’hoansi in Namibian community-based natural resource management. Society & Natural Resources 32(4), 417–33. doi:10.1080/08941920.2018.1550227

- Koot, S, Hebinck, P & Sullivan, S, 2020. Science for success—A conflict of interest?: researcher position and reflexivity in socio-ecological research for CBNRM in Namibia. Society & Natural Resources 365(6456), 1–18. doi:10.1080/08941920.2020.1762953

- Krishnan, A, 2017. Re-thinking the environmental dimensions of upgrading and embeddedness in production networks: The case of Kenyan horticulture farmers. University of Manchester, School of Environment, Education and Development. Manchester, UK.

- Kusenbach, M, 2003. Street phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography 4(3), 455–85. doi:10.1177/146613810343007

- Lee, J, Gereffi, G & Beauvais, J, 2012. Global value chains and agrifood standards: Challenges and possibilities for smallholders in developing countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(31), 12326–31. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913714108

- Lenggenhager, L, 2018. Ruling nature, controlling people: nature conservation, development and War in north-eastern Namibia since the 1920s. Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Basel.

- Lubilo, R & Hebinck, P, 2019. ‘Local hunting’ and community-based natural resource management in Namibia: Contestations and livelihoods. Geoforum 101, 62–75. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.020

- Mayring, P, 2000. Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 1(2), Art. 20.

- Mendelsohn, JM, 2006. Farming systems in Namibia. Research & Information Services in Namibia, Windhoek.

- Mosimane, AW & Silva, JA, 2015. Local governance institutions, CBNRM, and benefit-sharing systems in Namibian conservancies. Journal of Sustainable Development 8(2), doi:10.5539/jsd.v8n2p99

- NACSO, 2017. Namibia’s communal conservancies: Annual conservancy performance ratings & audit reports for the year 2017. NACSO.

- Naidoo, R, Gerkey, D, Hole, D, Pfaff, A, Ellis, AM, Golden, CD & Fisher, B, 2019. Evaluating the impacts of protected areas on human well-being across the developing world. Science Advances 5, 4. eaav3006. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav3006.

- Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA), 2019. The Namibia labour force Survey 2018 Report. Windhoek Namibia: Namibia Statistics Agency.

- Naziri, D, Aubert, M, Codron, J-M, Loc, NTT & Moustier, P, 2014. Estimating the impact of small-scale farmer collective action on food safety: The case of vegetables in Vietnam. The Journal of Development Studies 50(5), 715–30. doi:10.1080/00220388.2013.874555

- Nyambe, J & Belete, A, 2018. Analyzing the agricultural livelihood strategic components in the Zambezi region, Namibia. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology 24(2), 1–11. doi:10.9734/AJAEES/2018/28619

- Onwuegbuzie, AJ, Dickinson, WB, Leech, NL & Zoran, AG, 2009. A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8(3), 1–21. doi:10.1177/160940690900800301

- Ponte, S, 2019. Business, power and sustainability in a world of global value chains. Zed Books Ltd, London, UK.

- Ponte, S & Ewert, J, 2009. Which way is “up” in upgrading?: trajectories of change in the value chain for South African wine. World Development 37(10), 1637–50. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.03.008

- Republic of Namibia. 2017. Namibia’s 5th national development plan (NDP5): 2017 – 2022. Republic of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia.

- Ruppel, OC & Ruppel-Schlichting, K (Eds.), 2016. Environmental law and policy in Namibia: towards making Africa the tree of life. 3rd ed. Windhoek, Namibia.

- Schnegg, M & Kiaka, RD, 2018. Subsidized elephants: Community-based resource governance and environmental (in)justice in Namibia. Geoforum 93, 105–15. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.05.010

- Scoones, I, 1998. Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. Institute of Development Studies, IDS Working Paper 72.

- Scoones, I, 2009. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36(1), 171–96. doi:10.1080/03066150902820503

- Scoones, I, Marongwe, N, Mavedzenge, B, Murimbarimba, F, Mahenehene, J & Sukume, C, 2012. Livelihoods after land Reform in Zimbabwe: understanding processes of rural Differentiation. Journal of Agrarian Change 12(4), 503–27.

- Selwyn, B, 2013. Social upgrading and labour in global production networks: A critique and an alternative conception. Competition & Change 17(1), 75–90. doi:10.1179/1024529412Z.00000000026

- Silva, JA & Mosimane, A, 2014. “How could I live here and not be a member?”: economic versus social drivers of participation in Namibian conservation programs. Human Ecology 42(2), 183–97. doi:10.1007/s10745-014-9645-9

- Steinbach, D, Wood, GR, Kaur, N, D’Errico, S, Choudhary, J, Sharma, S, Rahar, V & Jhajharia, V, 2016. Aligning social protection and climate resilience: A case study of WBCIS and MGNREGA in Rajasthan: Working paper. IIED, London, UK.

- Vicol, M, 2019. Potatoes, petty commodity producers and livelihoods: contract farming and agrarian change in Maharashtra, India. Journal of Agrarian Change 19(1), 135–61. doi:10.1111/joac.12273

- Vicol, M, Fold, N, Pritchard, B & Neilson, J, 2019. Global production networks, regional development trajectories and smallholder livelihoods in the Global South. Journal of Economic Geography 19, 973–93. doi:10.1093/jeg/lby065

- Vicol, M, Neilson, J, Hartatri, DFS & Cooper, P, 2018. Upgrading for whom?: Relationship coffee, value chain interventions and rural development in Indonesia. World Development 110, 26–37. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.020

- Yobe, CL, Mudhara, M & Mafongoya, P, 2019. Livelihood strategies and their determinants among smallholder farming households in KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. Agrekon 58(3), 340–53. doi:10.1080/03031853.2019.1608275