?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper extends the empirical analysis of child health by simultaneously considering the effects and contributions of parental bargaining to the rural–urban child health differential in Tanzania, a country where most communities are patriarchal in nature. We use the Heckman two-step procedure to correct for possible sample selection bias. The results suggest that domestic violence towards female partners increases the probability of child stunting while female autonomy in decision-making and discretion over household resources reduce the probability of child stunting. The significance of these effects are mainly observed in rural than in urban communities. Differences in female autonomy between rural and urban areas account for 5% of the rural–urban gap in child nutrition. The contribution reduces to 4% after correcting for sample selection bias. Thus, empowering rural women is essential in reducing the rural–urban child health differentials.

1. Introduction

Early health conditions of children have persistent and profound impacts on many outcomes in adulthood (Currie and Almond Citation2011). The health capital of children is an important mechanism for explaining intergenerational transmission of educational attainment, economic status and overall human capital formation (Victora et al. Citation2008; Zivin and Neidell Citation2013). Thus, investment in child health pays off to the child, to the household and to the entire economy (Fleisher et al. Citation2010). However, the household remains an important unit of production, and investment in human capital of children (Kazianga and Wahhaj Citation2017). Despite several interventions, the levels of child malnutrition and mortality remain persistently high in many developing countries (Jamison et al. Citation2016). A number of studies have found that maternal socioeconomic and demographic factors are important determinants of child health (Grépin and Bharadwaj Citation2015; Jamison et al. Citation2016). This growing body of empirical literature has confirmed the association between women’s autonomy and reproductive health outcomes (Allendorf Citation2007; Kamiya Citation2011). Evidence on the relative bargaining power within couples on reproductive health outcomes has focused mainly on fertility decisions (Rasul Citation2008), the use of health services (Maitra Citation2004; Nikiéma et al. Citation2008; Kamiya Citation2011; Mukong and Burns Citation2019) and child survival (Ghuman Citation2003; Koppensteiner and Manacorda Citation2016).

Children malnutrition outcomes are generally better in urban than in rural areas (Smith et al. Citation2005). In developing countries urban children are, on average, better than rural children in a range of health outcomes (Van de Poel et al. Citation2007; Firestone et al. Citation2011). It is evidence that child stunting is more prevalent in rural compared to urban areas (Amare et al. Citation2020; Ameye and De Weerdt Citation2020). According to Headey et al. (Citation2018), rural children are more stunted with worse dietary outcomes compared to urban children. Children in remote rural areas were found to be experiencing only a small nutritional penalty. Evidence from 80 developing countries suggests that living in slums is associated with higher infant and child mortality (Jorgenson et al. Citation2012; Jorgenson and Rice Citation2012). In 18 African countries, it is evident that child mortality rates are significantly higher in slum than in non-slum urban areas, but still lower than in many rural areas (Güther and Harttgen Citation2012). Evidence from 73 low- and middle-income countries shows that higher health risks are common among slum than non-slum urban children but lower risks compared to rural children (Fink et al. Citation2014). However, only a few studies have shown that maternal socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are important contributing factors to the rural–urban gap in child health in developing countries (Van de Poel et al. Citation2009). The novelty of the current study is in two parts. First, examining the role of parental bargaining on the rural–urban gap in child stunting. Second, the paper accounts for sample selection that has been largely ignored in the literature.

In Tanzania, while there has been a significant reduction in child malnutrition over the years, the rural–urban gap in child stunting and underweight children remains significantly high. Detailing the malnutrition situation in rural and urban Tanzania, data from the 2015/16 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) indicates that about 25% of urban children are stunted compared to 38% in rural areas. The nutritional advantage that urban children enjoy suggest that the negative consequences associated with malnutrition may be more pronounced in rural than in urban areas. Several studies have shown that the nutritional difference between rural and urban areas is primarily due to a unique set of household and community characteristics (Van de Poel et al. Citation2007; Mussa Citation2014, Headey et al. Citation2018). A number of studies have examined the determinants of child health in Tanzania (Shiratori Citation2014; Chirande et al. Citation2015). To the best of our knowledge this is one of the first papers to examine the role of parental bargaining to the rural–urban gap in child health.

The significant contribution of this paper to the literature can be appreciated from the background that shrinking the rural–urban inequality in child health is an important pathway to achieving national and international child health targets for most third world countries. This paper extends the empirical analysis of child health by incorporating the effect and contribution of parental bargaining on the rural–urban gap in child health in Tanzania. Our empirical analysis uses appropriate techniques to account for the potential sample selection bias. The observed contribution of parental bargaining to the rural–urban gap in child nutrition could be biased if only the nutritional status of the surviving children is observed. That is, selectivity bias is the potential problem with decomposing the rural–urban gap in child nutrition (O’Donnell et al. Citation2008) and ignoring this understates this gap. This is because on average, child health outcomes have been shown to be better in urban than in rural areas of developing countries (Van de Poel et al. Citation2007; Srinivasan et al. Citation2013). The Heckman two-step sample selection procedure is used in an attempt to correct for the possible sample selection bias. Our results suggest that the rural–urban gap in child health is understated and the contribution of parental bargaining is overstated if sample selection bias is ignored.

Many key development outcomes depend on women’s participation in the economy and their ability to negotiate favourably in the allocation of resources within the household (Doss Citation2013; Vaz et al. Citation2016). Relative to men, women are noted for devoting a larger portion of their time and income to children’s overall well-being (Thomas Citation1993; Kabeer Citation1999). Thus, differences in the relative power of couples within households might explain the disproportionate share of child health across regions. However, women remain socially and economically disadvantaged in terms of education, employment, inheritance, credit and control over household resources (Blackden et al. Citation2006; Nikiéma et al. Citation2008). The gender gap in decision-making within couples and the prevalence rate of intimate partner violence against women are systematically larger in poor (rural) than in rich (urban) communities (Duflo Citation2012; Jayachandran Citation2015). This is detrimental to the health outcomes of rural children and further compounds the health problems of disadvantaged children (Koppensteiner and Manacorda Citation2016).

The opportunity cost of child upbringing (time devoted to child care) is lower for women than men (Ray Citation1998) and the economically disadvantaged women, rather than men, are directly involved in reproductive health practices (Rasul Citation2008). Culture and gendered institutions (norms) in many developing societies overrule and limit women’s bargaining power (Mabsout and Van Staveren Citation2010). Bargaining power within couples is likely dissimilar between rural and urban communities due to differences in female education, earnings, awareness of marital rights and gender institutions between these areas. Therefore, empowering women economically improves their power in household decision-making processes resulting in better maternal and child health outcomes (Caldwell Citation1986; Ghuman Citation2003).

Child health outcomes in Tanzania could, on average, be better than the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended standards, if health outcomes in rural communities are made similar to the prevailing urban levels. Similarly, the levels of female power in household decision-making and discretion over resources are relatively low in rural than in urban communities (). For example, over 65 percent of all households in urban communities cooperate in health care seeking decisions relative to 59 in rural areas. This suggests that the observed rural–urban gap in child health can partly be attributed to differences in female autonomy. Rather than rely on intuitive assumptions, this paper investigates the contribution of parental bargaining to the rural–urban gap in child health in Tanzania, where there is no evidence of what accounts for the rural–urban child health differential.

Table 1. Comparison of determinants of child health outcomes across urban and rural areas.

2. Estimation strategies

This paper uses both the ordinary least square (OLS) technique and the probit model. This is to ensure that our results are not driven by the chosen measure of child health. We decompose the observed rural–urban child nutritional gap using the detailed Oaxaca and Blinder decomposition. The child health equation is given as:

(1)

(1) Where i refers to the individual child, j is child residential type, Hi refers to child health status,

is a vector of determinants of child health, βi is a vector of associated parameter estimates and ϵi is a random error term. The standard Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition splits the rural–urban child health differential into the observed and unobserved portion as follows:

(2)

(2) Where I is an identity matrix equal to one if

is a scalar and not a vector, D is a matrix of weights,

(

) is the predicted mean nutrition outcome for a given group of children,

is the mean vector of explanatory variables,

is a vector of parameter estimates and Δ denote a change. When D = 0, the interaction effects are embedded in the unexplained portion, whereas when D = 1, they are embedded in the explained part. Such a decomposition will be sensitive to whatever group’s health outcome that is assumed to be the norm (Madden Citation2004). Neuman et al. (Citation1998) suggested that the coefficients from the pooled regression be used. We use the pooled model with a group indicator as an additional variable as explained in Jann et al. (Citation2008).

2.1. Decomposition with selection corrected

Child nutrition is observed only for living children and this might be a selective group. To fully comprehend the prevailing rural–urban gap in child nutrition, it is essential to vigorously evaluate the health of all children born during the period under study (O’Donnell et al. Citation2008). Thus, the nutrition and survival equations can be estimated simultaneously to correct for the possible sample selection bias:

(3)

(3) Where

is a dummy variable equivalent to one if the child is alive and zero if he/she is dead and

is a continuous variable that measures the nutritional status of children alive,

and

are vectors of explanatory variables,

are associated parameter vectors and

are error terms. The error terms follow a bivariate normal distribution of the form

. Nutritional status is observed for those whom

, so that the expected nutritional status of a surviving child is:

(4)

(4) Where

,

,

is the standard normal density function and

is the standard normal cumulative density function. The estimating equation of rural–urban nutrition for surviving children (in the presence of selectivity) is expressed as:

(5)

(5)

Equation (5) is estimated using the Heckman two-step estimation procedure and correction of selectivity bias requires the child health decomposition in the form:

(6)

(6)

is the predicted mean of height-for-age Z-score of children in a given group,

is the mean vector of child health determining variables,

is an estimate of

and

is an estimate of the mean Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR). The first two terms at the right of Equation (6), are the unexplained and explained portions of the gap in child health, respectively and the third term is the selectivity component.

2.2. Measures of child health

The anthropometric measures are used as a measure of child health. This measures distinguishes between short-term changes and long-term changes in child nutrition (Onis Citation2000; O’Donnell et al. Citation2008) and is based on three key indicators of child nutrition, namely, stunting, wasting and underweight. In each of these measures, child nutrition is expressed in the form of a Z-score by either comparing the height or the weight of a child to that of a similar child from a reference healthy population (Zere and McIntyre Citation2003).

The weight-for-height measure reflects acute malnutrition, but is sensitive to short-term changes, and is essential in evaluating benefits from nutrition intervention programmes. The weight-for-age measure cannot distinguish between short-term and long-term malnutrition and is therefore difficult to interpret. Wasting and stunting are therefore appropriate anthropometric measures, as they can discriminate between temporary and permanent malnutrition. The empirical analysis in this paper makes use of the stunting measure of child nutrition as it is the most appropriate measure of childhood malnutrition (Skoufias Citation1998). It is an overall measure of deprivation and is less sensitive to temporary food shortages (Svedberg Citation1990).

2.3. Measures of parental bargaining

This paper uses such non-economic factors (domestic violence, decision-making process, discretion over household resources and differences in age and education) as indicators of parental bargaining. In our data, there are five yes or no questions used to measure domestic violence. The questions are whether women were justifiably beaten by their partners when (1) they went out without telling their partner, (2) they neglected their children, (3) they argued with their partner, (4) they refused to have sex with their partner, and (5) they burnt food. We used these indicators and the principal component analysis to construct an index of domestic violence. For decision-making, women were asked whether or not they cooperate in decisions regarding household health care use and household daily purchases. Concerning discretion over household resources women were asked whether or not getting money from their partner to seek health care was problematic. Likewise, employment status of women is used to proxy for their discretion over economic resources (Ghuman Citation2003). The selection of these measures is guided by the literature on intra-household bargaining (Nikiéma et al. Citation2008).

2.4. Estimation issues

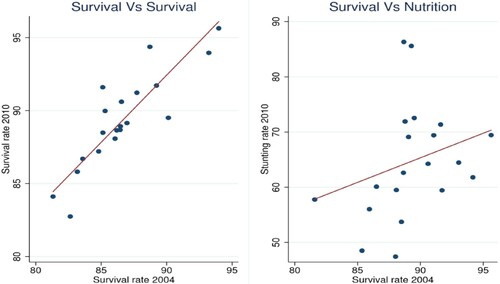

The use of Heckman two-step procedure automatically corrects for the sample selection problems highlighted in this study (Cameron and Trivedi Citation2005). In this paper, we use regional child survival rates in 2004 as an exclusion restriction for the 2010 child survival. The correlation coefficient for regional child survival rates in 2010 and 2004 is 0.81 (highly correlated), but the correlation coefficient for regional child stunting rate in 2010 and regional child survival rate in 2004 is 0.27 (). It should be noted that the reference population to which a child’s nutritional status is compared takes account of only children alive and thus it is less likely that current regional nutritional outcomes depend on previous regional survival rates. In addition, children observed in 2004 are independent of children observed in 2010. Data from the 2004/05 Tanzania Demography and Health Survey (TDHS) is used to compute regional child survival rates.

We acknowledge that any regional intervention could alter or reverse the survival or stunting trends, thereby reducing the strong association between previous regional survival rates and current stunting rates. Based on our knowledge, there have been no region-specific child health care policies in Tanzania within this period. In addition to the theoretical justification, the empirical results show that the regional child survival rate in 2004 is a significant predictor of child survival probability in 2010 (). For sensitivity analysis we decompose the rural–urban gap in child nutrition with and without selection and use a nonlinear decomposition by Fairlie (Citation2005) to decompose the rural–urban gap in child survival.

Table 2. Marginal effects of child survival rate in 2004 on child survival probability in 2010

3. Data and data analysis

We use the 2010 Tanzanian Demography and Health Survey (TDHS). This is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted by the Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). The survey is designed to provide a comprehensive picture of reproductive health outcomes, household background characteristics, and general living conditions in the country. For the purpose of this paper, we limited our sample to children aged 0–59 months, and further divided the sample into rural and urban sub-samples.

Results in reveal interesting differences in child health outcomes and parental bargaining indicators between rural and urban households. Malnutrition in this paper strictly refers to stunting, and the two terminologies are used interchangeably. As expected, child nutrition and survival outcomes are significantly better in urban than in rural areas. For instance, about 38% of rural children are stunted relative to 25% for urban children. The under-five survival rate is 89% in rural areas compared to 91% in urban areas. These are relatively higher than the survival rates of 86% for the rural sample and 89% for the urban sample in 2004.

In terms of parental bargaining attributes, there exist significantly low levels of cooperation in decision-making in rural households. In 60% of all rural households, partners cooperate in health care decisions relative to 69% of urban households. Rural women are more prone to domestic violence than their urban counterparts. For example, while over 43% of rural women are beaten when they argue with partners, only 33% of urban women are beaten when they argue with their partners. Household socioeconomic status is, on average, significantly better in urban than in rural areas. For example, only 20% of rural households belong to the high income quintile compared to 86% of urban households.

In , child stunting rates are significantly higher for violence prone households. For example, stunting is 5 percentage points higher in households where women are beaten when they went out without telling their partners. As expected, the rate of stunting is generally lower if couples cooperate in household decision-making processes. The stunting rate is 2 percentage points lower when couples cooperate in health care use decisions. Children of employed women are less likely to be stunted relative to children of unemployed women. A larger proportion of children from the poorest households (42%) are stunted, and only about 20% from affluent households are stunted. It is observed that the proportion of stunted children decreases with the level of household well-being.

Table 3. Mean comparison of child stunting across various characteristics.

4. Empirical results

presents the estimated effects of parental bargaining on child nutritional status. Panel A presents estimates from the probit model (dependent variable is 1 for stunted children and zero otherwise) and Panel B presents estimates from an OLS.Footnote1 The results suggest that child stunting increases with the level of female domestic violence. Women exposed to physical intimate partner violence in Tanzania are three time more likely to experience preterm delivery and low birth weight (Sigalla et al., Citation2017). The probability of child stunting is 7% higher among women with limited discretion over household wealth (column 1 of ). This confirms the argument that women’s limited discretion over household resources reduces their ability to seek care and to provide the required nutrients to their children (Ghuman Citation2003). Partner cooperation in health care use decisions, reduces the probability of child stunting by 9%. Partner cooperation in household daily purchase decisions reduces the probability of child stunting by 4%. This is in line with evidence from Bangladesh, suggesting that aspects of female bargaining power, including participation in health care decision, daily purchases are associated with better child health outcomes (Schmidt, Citation2012). Evidence in Tanzania suggest that an increase in wife’s bargaining power leads to a more gender-equal allocation to children (Ringdal & Hoem, Citation2017). Children of mothers with more bargaining power in rural Senegal are found to have better child nutritional status (Lépine & Strobl, Citation2013). These estimates are generally insensitive to the inclusion of maternal and household characteristics but vary significantly between the estimated approaches (Panel A and Panel B of for comparison). However, the OLS estimates are slightly different from the probit estimates in terms of level of significance when only rural and urban sub-samples are considered and household characteristics are included (Column 8 and 9 of for comparison). While it is difficult to provide a clear justification for this observation, it is important to note that this could be attributed to methodological differences or it could be that the different measures are sensitive to the inclusion of household characteristics.

Table 4. Marginal effects and regression estimates of parental bargaining including other controls.

4.1. Decomposition results

The decomposition analysis seeks to answer three fundamental questions. First, what is the child nutritional gap between rural and urban communities if the sample of children alive is random? This is given by the total gap without correcting for sample selection. Second, what would the nutritional gap be if the sample of children alive is not random? This is the total gap from a selectivity corrected child health equation. Third, what would the nutritional gap be if rural households were identical to urban households, except for differences in parental bargaining? This is the contribution of parental bargaining to the nutritional gap. To answer these fundamental questions, the detailed Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition with and without selection is used. The nutritional variable here is continuous with high values implying better nutritional outcomes. In addition, a generalised non-linear decomposition by Fairlie (Citation2005) is used to identify the contribution of parental bargaining to the rural–urban gap in child survival rates.

presents results from an extended decomposition of the rural–urban gap in child health, with an attempt to correct for selection bias. The gap is divided into the explained (due to differences in observable characteristics) and unexplained (due to differences in coefficients and unobservables). Without adjusting for sample selection, the average nutritional status (z-score) is −1.14 for urban children and −1.59 for rural children. These values decreased to −1.39 and −1.89 respectively after correcting for selection bias. The overall rural–urban gap in child nutrition is 0.45 and increased to 0.50 after correcting for sample selection bias. The results reveal that about 69% of the gap is explained by differences in the distribution of observable covariates between rural and urban regions. The total explained gap reduces to 62% after correcting for selection bias. In the non-linear decomposition, 79% of the gap in child survival is due to differences in observable characteristics. The results suggest that differences in household socioeconomic status remain the main drivers of the rural–urban gap in child nutrition, but this can be exacerbated by differences in parental bargaining. Failure to correct for sample selection bias underestimates the rural–urban gap in child health.

Table 5. Extended rural–urban child health decomposition (sample selection corrected).

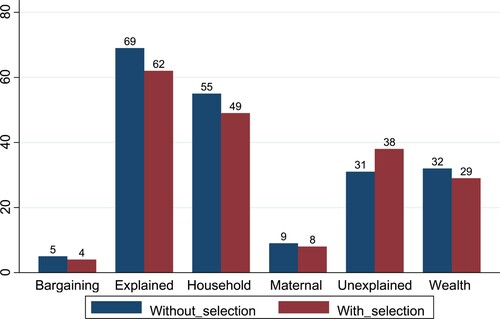

presents the contribution of each covariate to the observed rural–urban gap in child nutrition. Parental bargaining indicators account for 5% of the gap without selection and 4% with selection (6% of the total explained gap). Maternal and child specific characteristics account for 10.8% of the total gap without selection and 9.7% with selection (16% of the total explained gap). Differences in socioeconomic status between rural and urban households account for 78% of the total explained gap (53.4% without selection and 47.9% with selection). Van de Poel et al. (Citation2009) also confirmed that a greater part (67%) of the rural–urban gap in infant mortality is attributed to differences in household socioeconomic status.

Table 6. Detailed decomposition of rural–urban child nutrition correcting for sample selection.

Over half of the contributions of parental bargaining are from women’s limited discretion over household resources. Differences in domestic violence account for 0.1% of the gap, while differences in the level of cooperation in household decision-making account for 0.54% of the gap. The positive contribution of parental bargaining to the rural–urban gap in child health in Tanzania is as expected. Evidence suggests that better parental bargaining outcomes are associated with improved child health (Schmidt, Citation2012; Lépine & Strobl, Citation2013; Ringdal & Hoem, Citation2017; Sigalla et al., Citation2017). Since intimate partner violence and weak parental bargaining outcomes are generally higher in rural than urban Tanzania (Chegere, Citation2020), part of the observed differences is child health can be attributed to differences in parental bargaining. Differences in educational attainment between couples account for 0.52% and differences in age 0.2% of the gap. The contribution of each of these indicators reduces slightly after correcting for sample selection bias. The relative contributions of the observed factors to the explained and the unexplained gaps are presented in .

This paper has identified evidence of sample selection bias and how it affects the total gap in rural–urban child nutrition, due to observable and unobservable covariates. It is also observed that the increase in the overall gap after correcting for selectivity is explained by the unobservable characteristics. The results suggest that differences in household factors, especially household wealth, remain the main drivers of the rural–urban gap in child nutritional status. Maternal and child attributes are the second most important contributors to the gap; however, the role of differences in bargaining power within couples cannot be ignored. The results further suggest that failure to correct for possible sample selection bias results in underestimation of the rural–urban gap in child health.

5. Conclusion

This paper has investigated the contribution of parental bargaining to the rural–urban gap in child nutrition in Tanzania, a country where most communities are patriarchal with traditional norms, practices, and attitudes concentrated on male power, with limited legal protection of women.Footnote2 We argue that parents care about the health of their children, but their actions may affect child health inputs, which in turn affects child health. Therefore, increasing parental cooperation in household decision-making and female discretion over household resources can help reduce the rural–urban gap in child nutrition. This offers an attractive policy option, particularly when compared to the difficult alternative of household wealth redistribution. The study further suggests that the overall gap is likely to be underestimated if sample selection bias is not adequately addressed.

To check for the sensitivity of our results, different measures of child heath were used. A variety of parental bargaining attributes were used to examine the relationship between parental bargaining and the probability of child stunting. The results suggest that parental cooperation in decision-making, maternal discretion over household resources and domestic violence are significant determinants of child nutrition. The effects are significant mostly in rural but not in urban communities. The magnitude of the coefficients of parental bargaining is less sensitive to the inclusion of household characteristics. Taken together, the results suggest that maternal, child specific and household attributes are important in explaining the probability of child stunting.

The decomposition results suggest that differences in parental bargaining account for 4–5% of the rural–urban gap in child nutrition. The results confirm that over 69% of the gap is explained by differences in the distribution of observable child health determinants, whereas differences in unobservables account for 31% of the gap. The paper illustrates the significance of properly correcting for sample selection bias, as failure to do so clearly understates the gap. A bulk of the total explained gap is due to differences in household wealth. Poor child health and the rural–urban gap derived from differences in household and community factors can be exacerbated by the inability of parents to cooperate in their actions. From this perspective, we argue that policies need not be limited to correcting community deficiencies and household endowment, but should empower women as empowering rural women reduces the parental bargaining gap directly through discretion over resources and indirectly through their participation in household decision-making processes.

We acknowledge that parental bargaining estimates between rural and urban areas could be sensitive to differences in family composition or formation between these areas, that is, parental bargaining is only relevant if children live in two-parent households. However, the data used suggests that over 84% of women that had under-five children during this period were either married or living with a partner. Regarding rural and urban sub-samples, over 81% of women in the urban sample were either married or living with a partner relative to 85% for the rural sample. Thus, we are confident that the observed difference is less likely to significantly influence the results.

Acknowledgement

We wish to express our deep appreciation to African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) and Carnegie Foundation for the financial support to carry out this research. We are also grateful to the resource persons and members of AERC's thematic group A for various comments and suggestions that helped the evolution of this study from its inception to completion. We are indebted to the anonymous referees who reviewed the paper and provided comments and suggestions that helped in shaping and improving the overall quality of the paper. The findings made and opinions expressed in this paper are exclusively those of the author(s). The authors are also solely responsible for content and any errors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 It should be noted that the child health variable for the OLS is continuous (height-for-age Z-score) with high values indicating better nutritional outcomes and vice versa

2 World Bank (2013a) Women, Business, and the Law [database] http://wbl.worldbank.org/ (accessed 25 November 2013)

References

- Allendorf, K, 2007. Couples’ reports of women’s autonomy and health-care use in Nepal. Studies in Family Planning 38(1), 35–46.

- Amare, M, Arndt, C, Abay, KA & Benson, T, 2020. Urbanization and child nutritional outcomes. The World Bank Economic Review 34(1), 63–74.

- Ameye, H & De Weerdt, J, 2020. Child health across the rural–urban spectrum. World Development 130, 104950.

- Blackden, M, Canagarajah, S, Klasen, S & Lawson, D, 2006. Gender and growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Issues and evidence, number 2006/37, Research Paper, UNU-WIDER, United Nations University (UNU).

- Caldwell, JC, 1986. Routes to low mortality in poor countries. Population and Development Review 12(2), 171–220.

- Cameron, AC & Trivedi, PK, 2005. Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Chegere, MJ, 2020. Intimate partner violence and Labour Market outcomes in Tanzania. African Journal of Economic Review 8(2), 82–101.

- Chirande, L, Charwe, D, Mbwana, H, Victor, R, Kimboka, S, Issaka, AI, Baines, SK, Dibley, MJ & Agho, KE, 2015. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives in Tanzania: evidence from the 2010 cross-sectional household survey. BMC Pediatrics 15(1), 165. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0482-9

- Currie, J & Almond, D, 2011. Human capital development before age five. Handbook of Labor Economics 4, 1315–486.

- Doss, C, 2013. Intra-household bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries. The World Bank Research Observer 28(1), 52–78.

- Duflo, E, 2012. Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature 50(4), 1051–79.

- Fairlie, RW, 2005. An extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 30(4), 305–16.

- Fink, G, Gunther, I & Hill, K, 2014. Slum residence and child health in developing countries. Demography 51(4), 1175–97.

- Firestone, R, Punpuing, S, Peterson, KE, Acevedo-Garcia, D & Gortmaker, SL, 2011. Child overweight and undernutrition in Thailand: Is there an urban effect? Social Science & Medicine 72(9), 1420–8.

- Fleisher, B, Li, H & Zhao, MQ, 2010. Human capital, economic growth, and regional inequality in China. Journal of Development Economics 92(2), 215–31.

- Ghuman, SJ, 2003. Women’s autonomy and child survival: A comparison of Muslims and non-Muslims in four Asian countries. Demography 40(3), 419–36.

- Grépin, KA & Bharadwaj, P, 2015. Maternal education and child mortality in Zimbabwe. Journal of Health Economics 44, 97–117.

- Günther, I & Harttgen, K, 2012. Deadly cities? Spatial inequalities in mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review 38(3), 469–86.

- Headey, D, Stifel, D, You, L & Guo, Z, 2018. Remoteness, urbanization, and child nutrition in sub-Saharan Africa. Agricultural Economics 49(6), 765–75.

- Jamison, DT, Murphy, SM & Sandbu, ME, 2016. Why has under-5 mortality decreased at such different rates in different countries? Journal of Health Economics 48, 16–25.

- Jann, B, et al., 2008. A stata implementation of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Stata Journal 8(4), 453–79.

- Jayachandran, S, 2015. The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Economics 7(1), 63–88.

- Jorgenson, AK & Rice, J, 2012. Urban slums and children’s health in less-developed countries. Journal of World-Systems Research 18(1), 103–15.

- Jorgenson, A, Rice, J & Clark, B, 2012. Assessing the temporal and regional differences in the relationships between infant and child mortality and urban slum prevalence in less developed countries, 1990–2005. Urban Studies 49(16), 3495–512.

- Lépine, A & Strobl, E, 2013. The effect of women’s bargaining power on child nutrition in rural Senegal. World Development 45, 17–30.

- Kabeer, N, 1999. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30(3), 435–64.

- Kamiya, Y, 2011. Women’s autonomy and reproductive health care utilisation: empirical evidence from Tajikistan. Health Policy 102(2), 304–13.

- Kazianga, H & Wahhaj, Z, 2017. Intra-household resource allocation and familial ties. Journal of Development Economics 127, 109–32.

- Koppensteiner, MF & Manacorda, M, 2016. Violence and birth outcomes: evidence from homicides in Brazil. Journal of Development Economics 119, 16–33.

- Mabsout, R & Van Staveren, I, 2010. Disentangling bargaining power from individual and household level to institutions: evidence on women’s position in Ethiopia. World Development 38(5), 783–96.

- Madden, D, 2004. Labour market discrimination on the basis of health: an application to UK data. Applied Economics 36(5), 421–42.

- Maitra, P, 2004. Parental bargaining, health inputs and child mortality in India. Journal of Health Economics 23(2), 259–91.

- Mukong, AK & Burns, J, 2019. Bargaining power within couples and health care provider choice in Tanzania. African Development Review 31(3), 380–92.

- Mussa, R, 2014. A matching decomposition of the rural–urban difference in malnutrition in Malawi. Health Economics Review 4(1), 11.

- Neuman, S, Oaxaca, RL, et al., 1998. Estimating labour market discrimination with selectivity corrected wage equations: methodological considerations and an illustration from Israel, number 1915, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Nikiéma, B, Haddad, S & Potvin, L, 2008. Women bargaining to seek healthcare: norms, domestic practices, and implications in rural Burkina Faso. World Development 36(4), 608–24.

- O’Donnell, OA, Wagstaff, A, et al., 2008. Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. World Bank Publications, Washington, DC.

- Onis, Md, 2000. Measuring nutritional status in relation to mortality. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(10), 1271–4.

- Rasul, I, 2008. Household bargaining over fertility: Theory and evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Development Economics 86(2), 215–41.

- Ray, D, 1998. Development economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Ringdal, C & Hoem Sjursen, I, 2017. Household Bargaining and Spending on Children: Experimental Evidence from Tanzania. NHH Dept. of Economics Discussion Paper, (19).

- Schmidt, EM, 2012. The effect of women’s intra-household bargaining power on child health outcomes in Bangladesh. Undergraduate Economic Review 9(1), 4.

- Shiratori, S, 2014. Determinants of child malnutrition in Tanzania: a quantile regression approach, Technical report.

- Sigalla, GN, Mushi, D, Meyrowitsch, DW, Manongi, R, Rogathi, JJ, Gammeltoft, T & Rasch, V, 2017. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and its association with preterm birth and low birth weight in Tanzania: A prospective cohort study. PloS One 12(2), e0172540.

- Skoufias, E, 1998. Determinants of child health during the economic transition in Romania. World Development 26(11), 2045–56.

- Smith, LC, Ruel, MT & Ndiaye, A, 2005. Why is child malnutrition lower in urban than in rural areas? evidence from 36 developing countries. World Development 33(8), 1285–305.

- Srinivasan, CS, Zanello, G & Shankar, B, 2013. Rural-urban disparities in child nutrition in Bangladesh and Nepal. BMC Public Health 13(1), 581.

- Svedberg, P, 1990. Undernutrition in sub-saharan Africa: Is there a gender bias? The Journal of Development Studies 26(3), 469–86.

- Thomas, D, 1993. The distribution of income and expenditure within the household. Annales d’Economie et de Statistique 29, 109–135.

- Van de Poel, E, O’Donnell, O & Van Doorslaer, E, 2007. Are urban children really healthier? Evidence from 47 developing countries. Social Science & Medicine 65(10), 1986–2003.

- Van de Poel, E, O’donnell, O & Van Doorslaer, E, 2009. What explains the rural-urban gap in infant mortality: household or community characteristics? Demography 46(4), 827–50.

- Vaz, A, Pratley, P & Alkire, S, 2016. Measuring women’s autonomy in Chad using the relative autonomy index. Feminist Economics 22(1), 264–94.

- Victora, CG, Adair, L, Fall, C, Hallal, PC, Martorell, R, Richter, L, Sachdev, HS, Maternal, G & et al, CUS, 2008. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. The Lancet 371(9609), 340–57.

- Zere, E & McIntyre, D, 2003. Inequities in under-five child malnutrition in South Africa. International Journal for Equity in Health 2(1), 7.

- Zivin, JG & Neidell, M, 2013. Environment, health, and human capital. Journal of Economic Literature 51(3), 689–730.