ABSTRACT

In 2012, the South African and German governments agreed to embark on a co-operative initiative to enhance violence and crime prevention in the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality. This initiative culminated in the Safety and Peace through Urban Upgrading (SPUU) programme, which was to be implemented in the community of Helenvale in Port Elizabeth. This article presents an interdisciplinary perspective on this initiative to determine its effectiveness in addressing crime, violence, socio-economic and spatial deprivation in the Helenvale community. Helenvale is afflicted by various challenges relating to crime and violence, but the most significant of these is undoubtedly gangsterism. The community has the dubious distinction of being perceived as the centre of gangsterism in the entire city. The importance of space and social marginalisation and the influence of these on violence and crime are explored. The authors employ anthropological, criminological and socio-spatial analytical approaches to interrogate the SPUU initiative, and, where necessary, suggest possible areas for revision or improvement in order to identify alternative ways to improve safety and the quality of life of the Helenvale community.

1. Introduction

The community of Helenvale in the city of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, is one of several communities that make up what are commonly referred to as the northern areas of Port Elizabeth. According to the We Care Project Initiative, a non-profit organisation founded in 2007, and that specialises in community development in the northern areas, approximately 182,000 of the 1.5 million inhabitants of Port Elizabeth live in the northern areas, also known as the Northern Suburbs (We Care Citationn.d.). The organisation stresses that the communities of the northern areas are hard hit by various challenges. According to the organisation’s website,

Daily our communities face some form of crisis, disaster or situation … The community members are currently downcast and stuck in a perpetual cycle of poverty, sickness, crime and hopelessness and therefore do not progress but regress and are in need of bold moves to be taken towards poverty eradication, medical relief, un-employment [sic] eradication, crime eradication and TOTAL eradication of ALL other known cancers killing our communities’ livelihood and hopes … (We Care Citationn.d.)

Much of the development initiatives in Helenvale are based upon the Safety and Peace through Urban Upgrading (SPUU) programme, which was started in 2012 as a joint initiative between the South African and German governments. However, not much progress appears to have been made under this initiative. One of the most significant challenges in Helenvale, gangsterism and gang-related crime and violence, continues to hamstring the community, and also has a direct impact on the successful implementation of projects. So the broad question that the authors seek to address is: how effective is the SPUU initiative in Helenvale? Within this question is another related question: what are the strengths and weaknesses of the SPUU programme? In our efforts to address these questions, the authors apply an interdisciplinary approach that encompasses anthropological, criminological and socio-spatial analytical perspectives to interrogate the SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan document that encapsulates the blueprint for the SPUU programme. This approach allows the authors to provide a critical reflection on the SPUU, and to gauge its effectiveness as an Integrated Community Development Programme (ICDP).

2. Outline of the historic, spatial, social, economic and other challenges affecting the Helenvale community

Many of the challenges facing the Helenvale community in the present have their origins in the past. Like most of the coloured communities in South Africa, Helenvale, along with the other coloured suburbs of the northern areas of Port Elizabeth, was the result of the forced removal and resettlement of coloured people under the Apartheid government’s Group Areas Act of the 1950s. According to the Affordable Land and Housing Data Centre (Citation2018), the township of Helenvale, which the Centre describes as ‘one of the oldest in Port Elizabeth’, was established ‘at the end of the 1950s as an Apartheid era Group Area for Coloureds.’ In terms of the Group Areas legislation, communities were divided into various designated residential areas on the basis of race, hence, in Port Elizabeth, the northern areas became the designated residential areas for those persons classified as coloured by the Apartheid government. However, as was characteristic of Group Areas, African and coloured communities were left under-developed and under-serviced in terms of infrastructure such as housing, land, sanitation, and various other amenities and basic services. Helenvale particularly suffered the consequences of an increasing population density without the necessary development of infrastructure. As a result, various spatial, social, economic and other challenges emerged, many of which are still a reality in the community, despite the formal ending of Apartheid era legislation such as Group Areas.

In order to contextualise some of the challenges affecting the community, it is necessary to shed some light on the specific issues impacting on the coloured people of South Africa in general, and those in Helenvale in particular. One of the key factors that directly and indirectly impacts on communities such as that of Helenvale is the issue of past and present coloured identity dynamics. Much has been written about the historical and contemporary dynamics affecting coloured people’s perceptions of their own identity, as well as the perceptions of others about coloured identity (see, for example, Du Pre Citation1992; Erasmus Citation2001; Adhikari Citation2006, Citation2006b, Citation2008; Petrus and Isaacs-Martin Citation2012; Petrus Citation2018 forthcoming). Of particular relevance to the current discussion is the question of what is meant by coloured identity. This is an important aspect because the perceptions and meanings attached to coloured identity have a direct bearing on the context of particularly poor coloured communities, in terms of how they see themselves and why. The notion of coloured identity is a complex one, and this complexity makes it difficult to define. However, Petrus and Isaacs-Martin (Citation2012:88) provide the following broad definition:

The authors use the concept coloured identity to refer to a dynamic and fluid identity belonging to a specific group in South Africa, most often attributed to persons of mixed racial and ethnic descent who, over time and due to specific historical, social, cultural and other factors, have undergone various changes in their perceptions of their identity as Coloured people. The meaning(s) of the concept is much wider than merely race or ethnicity …

While race and ethnicity emerged as a symbol of inferiority for Coloured persons during the colonial period, after 1950 the meaning of coloured identity as an inferior identity became even more entrenched … [C]oloured identity took on the meanings not only of racial and ethnic inferiority, but also of marginalisation, as Coloured people were viewed as not belonging to any of the ‘recognised’ groups in South Africa.

After 1994, the formal ending of Apartheid saw various reactions from within the coloured population ranging from outright rejection of the identity to acceptance, to a redefinition of the identity within the indigenous Khoi and San identities. In a sense, these reactions can be attributed to the perceived ongoing fears of many coloured people that they may find themselves worse off than they were under Apartheid, especially in terms of access to resources.

The above insecurities are exacerbated in communities such as Helenvale, and often manifest in various ways including the emergence of gangs, and other social problems. Gangs, and the related problems of gang violence and gang-related crimes, are perhaps the most serious challenges facing poor coloured communities in both the Western and Eastern Cape provinces. Recent studies by Petrus (Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2017a), as well as by Petrus & Kinnes (Citation2018) suggest that gangsterism poses serious challenges not only to the communities affected by them in both the Cape Flats (Western Cape) and northern areas of Port Elizabeth (Eastern Cape), but also to governance and authority structures in these areas. In both regions, gangsterism has become such a threat to safety and security that community residents and officials have called for the army to be deployed to affected areas (Petrus Citation2014; Setokoe Citation2017; Spies Citation2017).

In terms of socio-spatial challenges, Helenvale is arguably the most negatively affected residential area in Port Elizabeth. As indicated earlier in the discussion, Helenvale was one of several residential areas or townships created for coloured people displaced under the Group Areas legislation of the 1950s. Displacement, coupled with under-development and under-servicing of the community, contributed to various social and other problems. According to the Affordable Land and Housing Data Centre (Citation2018), Helenvale can be regarded as one of the poorest communities in Port Elizabeth. In addition, the community is characterised by high unemployment, poor education levels, high levels of substance abuse, violence and prostitution. Rampant gangsterism has already been briefly outlined earlier. One of the main factors that have contributed to these issues is housing. Again with reference to the Affordable Land and Housing Data Centre (Citation2018), the housing situation in Helenvale can be characterised as follows:

Typically, most residents are accommodated in small state provided houses, most of which date back from the Apartheid era council-house (see the next point for a description)

Most houses are joined in rows to form rectangular blocks of joined units of four or two, with very little space between blocks; consequently, children have to play in the streets where they may be exposed to other dangers

Almost 80% of the houses have one or two shacks [small units constructed from low cost materials such as corrugated iron, cardboard or plastic] usually found in the backyard; these shacks have no sanitation facilities, and may be rented out to relatives or other families, thereby compounding the space problem

There is a problem with groundwater penetrating floors

Although houses may have access to some sanitation facilities, these are often overloaded due to the burden of population density

Public spaces are poorly managed

Most residents are dependent on public transportation

It should, however, be noted that there has been some housing development in Helenvale. The township can be divided into two parts, namely ‘old’ Helenvale, characterised predominantly by the above factors, and ‘new’ Helenvale, which is located further up on a steep slope, and is characterised by Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) housing structures (Petrus Citation2018; SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014:14). Unfortunately, many of these structures are sub-par, and possess structural weaknesses that make them less than ideal for human occupation.

The range of challenges in Helenvale caused the township to be singled out for high priority upgrading and development. In 2007, former mayor of Nelson Mandela Bay, Nondumiso Maphazi, launched an urban renewal project worth seventy-eight million rands specifically for the development of Helenvale (Petrus Citation2018; Mandela Bay Development Agency Citation2014). Furthermore, the Safety and Peace through Urban Upgrading programme was also initiated ‘to invest in interventions that will create a safer Helenvale through projects that focus on both physical and social infrastructure’ (Mandela Bay Development Agency Citation2014).

However, the ongoing above challenges in Helenvale have prompted several key questions relating to the SPUU initiative. How effective has this programme been in the community? And what are its strengths and weaknesses? The following part of the discussion will focus on addressing these questions through a critical reflection on the SPUU project.

3. Analysis of and critical reflection on the Safety and Peace Through Urban Upgrading (SPUU) initiative: an interdisciplinary perspective

The authors have favoured an interdisciplinary approach for critically analysing the SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan. The motive for using such an approach is that it allows for a holistic and more in-depth analysis and interpretation. Consequently, anthropological, criminological and socio-spatial perspectives inform the selected interdisciplinary approach. These perspectives underpin the approach because each of them speaks to what the authors consider to be the main aspects impacting on the Helenvale community. As pointed out in the earlier discussion, issues of coloured identity, culture and heritage, as well as gangsterism and gang violence, and socio-spatial concerns all contribute to the overarching culture that characterises the Helenvale community. Thus, an interdisciplinary approach informed by anthropological, criminological and socio-spatial perspectives can be useful in analysing the SPUU Masterplan in reference to these main aspects.

3.1. Geographical context and spatial location of Helenvale

The Helenvale residential area is located approximately twenty-five kilometres from the Port Elizabeth central business district and, as indicated earlier, forms part of the northern areas. Helenvale consists of four parts or sections. ‘Old’ Helenvale comprises ‘Helenvale Proper’ and Die Gaat [The Hole], while ‘new’ Helenvale comprises Extension 12 and Barcelona. Helenvale’s physical features represent the physical divisions between the four sections. According to the Inception Report and Masterplan (Citation2014:14), three distinguishing physical features in the form of steep slopes separate and isolate the various sections from each other. These divisions are further worsened by gang wars to control different areas, particularly those in ‘old’ Helenvale. The socio-spatial division between ‘old’ Helenvale and ‘new’ Helenvale is noticeable, where the latter is characterised by some form of housing development, while the former is characterised by the old Apartheid-era housing infrastructure.

3.2. Background to the SPUU project and Masterplan

The SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan is an eighty-three page document that is divided into several main sections. These include an executive summary; background, general purpose and methodology; challenges and potentialities of the programme area; the programme concept; and, finally, the SPUU Masterplan itself (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan, Citation2014:i).

The background to the project, as outlined in the first section of the report, described the origins of the project, as well as its purpose. The SPUU programme for Helenvale was the culmination of a co-operative agreement relating to the achievement of socio-economic and political stability between the governments of South Africa and Germany. Helenvale was identified as the target community for the project because of the extent of social and economic challenges in the community. The Mandela Bay Development Agency (MBDA) was appointed as the Project Executing Agency. The project was co-financed by the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality (NMBM) and the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), with the details for implementation of the project agreed upon on 5 December 2012 (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan, Citation2014:6). The main objective of the project was to

contribute to increased safety and a better quality of life in Helenvale … through interventions in five SPUU Programme components … namely safety in public space, safety in schools, improved perspectives for youth, reduction in domestic violence and improvement in living space (housing) (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan, Citation2014:6).

3.3. Critical reflection on the SPUU Masterplan (Component 1: job creation through upgrading of public spaces and infrastructure)

As referred to earlier, the SPUU Masterplan identified five key components for targeted interventions. The implementation for four of the components was done in August and October 2014 (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan, Citation2014:41). One of the objectives of the public space and infrastructure development project (component 1) was the creation of short-term employment for community members (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan, Citation2014:45). However, although this appeared to be a good strategy in the short-term, in the medium to long-term this has created further challenges. Given that unemployment is a major challenge in Helenvale, it is reasonable to expect that unemployed community members would compete for the short-term work opportunities. Unfortunately, when this short-term work expired, many of those who benefitted simply went back to being unemployed. Furthermore, the limited work opportunities in the project exacerbated competition and potential conflicts between community residents. A third problem was that those community members who volunteered to work on projects started to expect, and even demand payment. Hence, these issues hampered the effectiveness of the project.

3.4. Critical reflection on the SPUU Masterplan (Component 2: safer schools)

As indicated in the report, the main objective of the safer schools component was to develop and implement systems of violence prevention and conflict management in the four schools in Helenvale, and to do this in partnership with the community (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan, Citation2014:46). This objective was based on four main principles:

Building community partnerships that promote a sense of community ownership of schools and involve parents in their children’s schooling

Strengthening school governing bodies to create safe environments for learners and teachers

Mobilising school support networks to protect learners

Promoting optimum development of learners

While each of these principles is laudable, there are however various challenges that negatively affect the implementation of these principles. Firstly, one major challenge is that many learners in the community are in single-parent families, or in families headed by grandparents. In addition, many households are affected by substance abuse and domestic violence among parents. Thus, it is difficult to see how parents could see the value in becoming involved in their children’s schooling if these problems are not addressed.

Second, creating safe school environments requires first addressing the existing subcultures of violence that exist in the schools. Petrus (Citation2017b), for example, identified the stone-throwing subculture among school boys as a significant precursor to involvement in gangsterism. In fact, Petrus (Citation2017b:46) found that ‘Gangs start with the stone-throwing (sub)culture’ as many of the children who become involved in this are recruited into existing gangs, or even form new gangs.

Thirdly, the last principle of promoting the optimum development of learners is confronted by the major challenge of factors affecting the learning abilities of children. While environmental factors such as gangsterism, violence, socio-economic deprivation and poor facilities play a role, another key factor is learning difficulties created by foetal alcohol syndrome. A study conducted by the Foundation for Alcohol Related Research in 2016, found that Grade One learners in fourteen schools (including Helenvale) in Port Elizabeth had foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (Ellis Citation2016; Wadvalla Citation2016). The problem of foetal alcohol syndrome is symptomatic of the underlying (sub)culture of poverty, as identified and described by anthropologist Oscar Lewis in 1966. According to Lewis (Citation1966:21), the culture of poverty ‘represents an effort [on the part of the poor and marginalised communities] to cope with feelings of hopelessness and despair that arise from the realization … of the improbability of their achieving success in terms of the prevailing values and goals.’ The values and associated behaviours of this subculture are transferred to successive generations and thus, typically, perpetuate themselves. Substance abuse is one of the behaviours emanating from the subculture of poverty, and this is where the problem of foetal alcohol syndrome begins. Thus, promoting the optimum development of learners should involve a two-pronged approach. First, attention must be paid to addressing the root causes of foetal alcohol syndrome, and second, special facilities need to be made available for learners already affected so that they do not become school drop-outs and consequently find themselves easy targets for gang recruitment or other forms of criminal activity.

3.5. Critical reflection on the SPUU Masterplan (Component 3: perspectives for youth)

In some ways, this part of the Masterplan was perhaps the most important, especially since the major challenge of gangsterism in Helenvale mostly impacted on the youth. The perspectives for the youth component were organised around the following four interventions: career guidance; skills training for employability; entrepreneurial support; and lastly waste management for job creation (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan, Citation2014:53).

It cannot be disputed that the above interventions are all significant for youth development in Helenvale. However, what is lacking is the need to address issues of heritage and identity among the youth. One of the mechanisms to break the subculture of poverty intergenerational spiral is to attempt to change the prevailing negative value system among the younger generations. This could be done by instilling a sense of pride in the youth for who they are by highlighting the specific contribution that they can make to their community and to society at large. One of the consequences of the subculture of poverty is that the marginalised poor feel themselves alienated from the wider society, and respond to this alienation by rebelling against the very society that they hold responsible for their situation. The gangs represent symbols of rebellion against this perceived marginality (Petrus Citation2018), and since the gangs are mostly involving the youth, it could be argued that the youth themselves are driving this rebellion. It has been argued (Petrus Citation2013:74) that historical and contemporary coloured identity dynamics have played a significant part in the proliferation of gangsterism in the predominantly coloured residential communities of the northern areas, and Helenvale is perhaps the most significant illustration of this. Hence, any programme aimed at youth development in Helenvale would need to include a programme on heritage and identity, as this would assist in addressing some of the root causes of perceptions of marginalisation.

3.6. Critical reflection on the SPUU Masterplan (Component 4: domestic violence prevention)

According to the Masterplan, domestic violence had a particularly negative impact on children and youth. It was found that sixty-six percent of school-going children were beaten, and that they were more likely to be violent themselves, to abuse substances and to become involved in gangs (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014:59-60). The Masterplan proposed three interventions to address this challenge: strengthening social services delivery by the Department of Social Development; integration with current service provision and school-based networks; and the establishment of a one-stop victim care centre (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014:60).

Again, as indicated earlier, domestic violence, like gangsterism, substance abuse and the various other social challenges in the community, are all linked to the prevailing subculture of poverty. While the above measures may be useful in dealing with the short-term issues relating to domestic violence, they appear to be more reactive than pro-active. Long-term and pro-active interventions would need to address the underlying subculture of poverty, otherwise any intervention will be merely addressing the symptoms of the problem rather than getting down to the root causes. While the short-term interventions highlighted above are necessary to deal with already existing cases, the medium and longer-term interventions should be included to address the underlying causes.

3.7. Critical reflection on the SPUU Masterplan (Component 5: living space)

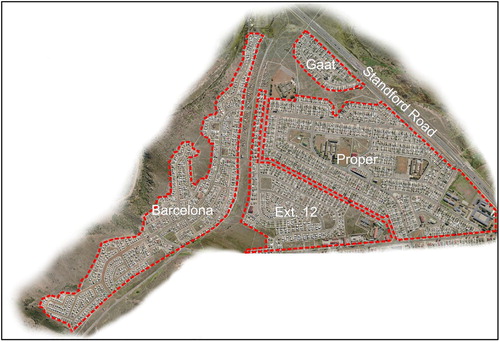

Helenvale had an estimated population of 21,236 during 2014 and consists of four sub-areas, namely Helenvale Proper, Die Gaat (The Hole), Allan Heights and Barcelona (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014) (See ). As indicated earlier, Helenvale was conceived as a township for coloured residents that were forcefully removed from inner city areas of Port Elizabeth during the Apartheid era. Helenvale was, from the outset, established as a low-income residential area, much different from the socially and racially mixed inner-city neighbourhoods from where most of its residents originated. Thus, from its inception, the design and composition of this township were, therefore, not conducive for its development as a functional and sustainable area.

Figure 1. Helenvale Sub-Areas (Source: SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014).

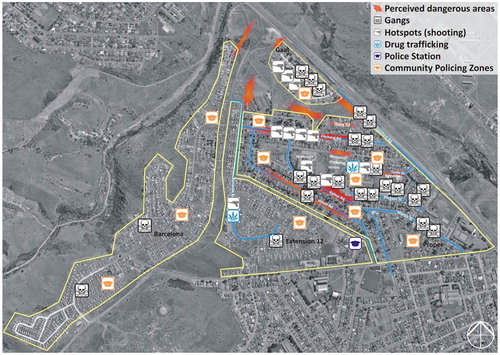

Helenvale is located on steep slopes and the separation of sub-areas is exacerbated by the control of different areas by opposing gangs and political parties (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014). The isolation of different sub-areas was also a conscious approach by Apartheid planners to ensure better control of townships by the security forces during periods of political turmoil and social unrest .

Figure 2. Helenvale Areas of Separation and Conflict (Source: SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014).

Helenvale Resource Centre was completed in 2013 and has become a landmark facility in this impoverished community. The area is well served with primary school and secondary school facilities as well as the nearby Gelvandale Magistrates Court and the Gelvandale Police Station. The SPUU Masterplan included improvement of living spaces such as pedestrian walkways, sports fields, the refurbishment of schools, a pilot housing project, street lighting and landscaping along roads. Criteria for the identification and prioritisation of projects included the contribution to conflict reduction; benefit to pedestrians, especially children; the impact on and connection to the transportation network; and the link with other components of the SPUU programme. The Masterplan noted that most of the gang conflict and vandalism in public spaces occurred in the older areas of Helenvale Proper and Die Gaat, and in the open spaces along the arterial routes. Most of the roads and several public parks have been upgraded, while the Integrated Public Transport System (IPTS) covering the metro area includes Stanford Road and Gail Road, two of the main roads in the community. These interventions will be supported by crosscutting organisational processes, comprising forums and networks between educators, school governing bodies and parents.

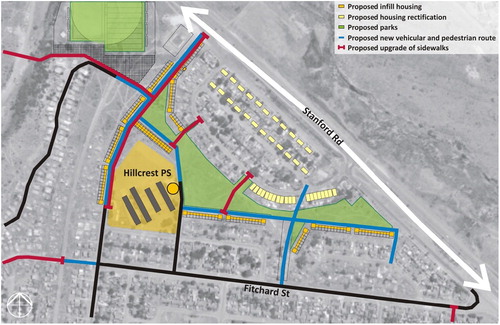

The Masterplan notes that although these developments have improved the status of physical infrastructure considerably, the upgrading of public spaces has not reduced conflict and vandalism, while the environment has remained unconducive to teaching and learning. This has resulted in the upgrading programme being placed on hold, while formal and community policing were explored. Consequently, pedestrian walkways have remained incomplete, street lights have been vandalised, high mast lights are non-functional, the Resource Centre is underutilised, while an informal settlement, consisting of some 150 structures was established in the road reserve. Housing remains, however, the major concern for residents and the most significant underlying reason of stress and violence in Helenvale. Concerns include the dilapidated and small size of the housing units and the increasing number of backyard dwellings due to overspill from the brick structures. The Masterplan proposed a pilot housing project in addition to the improvements of sidewalks and parks (SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014). shows an extract of the pilot housing proposals.

Figure 3. Pilot Housing Proposals (Source: SPUU Inception Report and Masterplan Citation2014).

4. The dialectic between people and space

John Western’s (Citation1982) classic on Outcast Cape Town reflects on the impact of forced removals on coloured residents from inner city areas to the Cape Flats. Western

recognises the dialectic of person and place … that people create places, that the structure of society is inevitably mirrored in the form of the city, although probably with a time lag because social relations can metamorphose more quickly than concrete and clay (Citation1982:4).

The critical reflection on Component 5 of the SPUU plan, dealing specifically with living space, illustrates the argument above, namely that spatial location derives from a position in society. As was the case with coloured residential areas in Cape Town, the Helenvale community was deliberately created as a marginalised space for a marginalised people. The creation of Helenvale as a deliberately under-developed, under-resourced, vulnerable and fragile space provided the environmental context for the kinds of social challenges and problems discussed to flourish. Hence, the relationship between space and community plays itself out, with the negative characteristics of the spatial environment reflected in the negative conditions and dynamics inherent in the community.

4.1. Social production of space

Henry Lefebvre’s theory on the social production of public spaces, the representation of racial identities and the existence of subject identity and material urban spaces in a mutually constitutive relationship (McCann Citation1999) has relevance. Lefebvre’s conceptual triad consists of representations of space (the abstract space of economist, planners and bureaucrats, constructed through discourse), representational space (the space of the imagination through which life is directly lived, for example the work of artists, photographers, filmmakers and poets), and spatial practices (the everyday routines and experiences that ‘secrete’ their own social space) (McCann Citation1999). These are also referred to as conceived, perceived and lived spaces. McCann (Citation1999) argued that space is continually produced and reproduced, for example by the media, and by the state and images from the black community of a segregated city with social and physical barriers and this results in racialized geographies in, for example, American cities. This perception of separate spaces reflects the differentiated experiences, perceptions and imaginations of the city by diverse residents.

These differentiated views are also evident in Helenvale, with conceived space reflected in products and processes associated with the municipality and the SPUU programme, contrasting with the perceived spaces by those involved, for example, with gang-related activities and divergent with the horrid lived reality of residents that are striving to survive in this hostile environment. Townships are consistently reproduced by the media as negative spaces and this has significant impact on private (including household) investment patterns in structures such as dwelling units, with only informal and marginalised activities finding spaces to exist.

However, an argument can be made that people do have agency to influence their place. In a critique of Lefebvre’s idea of the social production of space, Unwin (Citation2000:27) argued that ‘Whereas we cannot change space–time, we do have the means to influence place.’ This suggests that people do have agency to influence their spatial environments, whether for the better or for the worse. Unwin (Citation2000:27) further asks the questions of ‘how’ do we influence place, and ‘for whom’? Both of these questions directly impact on the spatial concerns pertaining to Helenvale. Given the already discussed social and spatial context of Helenvale, and the argument that contemporary social challenges, such as gangsterism, are a product of of this context, is it possible that the people of Helenvale are able to influence this context for the better? If it is possible, how would they be able to do that, and who would benefit? The SPUU is an attempt to answer these questions, and time will tell to what extent the programme will be deemed successful in empowering the community to utilise its agency to positively influence the environment.

It is therefore argued that Helenvale was politically, socially and economically conceived and constructed as a dormitory and dysfunctional township wholly for impoverished coloureds. The area’s location far from the city centre with its social, economic and recreational opportunities, as well as the absence of diversity in terms of income and social classes, significantly undermine the possibility of transforming Helenvale into a healthy, coherent and thriving neighbourhood. Helenvale epitomises the worst of the Apartheid planning experiment, and its continued existence locks its residents into a continued downward spiral of deprivation and marginalisation. The interventions attempted by the SPUU programme can at best be regarded as scratching the surface, or putting plasters on a ghetto deliberately created by the Apartheid state. It is argued that what is rather required is the complete reconstruction of this neighbourhood, the dispersal of poorer residents throughout the city, the generation of mixed land uses, mixed income and mixed social class neighbourhoods, interconnected through a web of communication, transportation and economic transactions, drawing on lessons from neighbourhoods with the social, spatial and economic structures that existed before the Apartheid state began with this destructive social engineering programme.

5. Conclusion

There is little doubt that vulnerable and fragile communities are the most difficult to develop because of the many challenges and obstacles that they face. However, despite the perceived difficulties, vulnerable communities need to be prioritised for development initiatives. The community of Helenvale has been singled out as a priority site for urban upgrading and development. This article has sought to critically reflect on a development initiative that has been in operation in the target community for just over five years. An interdisciplinary perspective revealed that while the SPUU programme appears to be a viable initiative, there are aspects of it that require some reconsideration. This article has highlighted the main components of the programme and has attempted to show where some of the shortcomings of the programme are, particularly in relation to each of the programme components. What emerges from this critical reflection is the fact that while the programme can be effective, there are weaknesses in it that require attention. No development programme is completely without any flaw, and by no means do the authors argue that the Helenvale SPUU programme should be perfect. However, it is the authors’ contention that, firstly, development practitioners and stakeholders should be aware of the weaknesses in the programme, and secondly, sufficient attention should be given to addressing those weaknesses as far as possible. This could only serve to enhance the strengths and effectiveness of the programme, thereby improving the chances that the programme delivers on what is expected.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adhikari, M, 2006a. Hope, fear, shame, frustration: Continuity and change in the expression of coloured identity in white supremacist South Africa, 1910-1994. Journal of Southern African Studies 32(3), 467–87.

- Adhikari, M, 2006b. ‘God made the white man, god made the black man … ’: Popular racial stereotyping of coloured people in apartheid South Africa. South African Historical Journal 55, 142–64.

- Adhikari, M, 2008. From narratives of miscegenation to post-modernist re-imagining: Toward a historiography of coloured identity in South Africa. African Historical Review 40(1), 77–100.

- Affordable Land and Housing Data Centre, 2018. http://www.alhdc.org.za/static_content/?p=1930 Accessed 11 June 2018.

- Du Pre, R, 1992a. Strangers in their own country: A political history of the “Coloured” people of South Africa 1652-1992 – an introduction. Southern History Association, East London, South Africa.

- Ellis, E, 2016. Shocking levels of foetal alcohol syndrome in Bay, Herald Live, 15 April, accessed at: http://www.heraldlive.co.za/news/2016/04/15/northern-areas-thought-highest-rate-world/ (16 February 2018).

- Erasmus, Z, 2001. Coloured by history, shaped by place: New perspectives on coloured identities in Cape Town. Kwela Books, Cape Town.

- Lewis, O, 1966. The culture of poverty. Scientific American 215(4), 19–25.

- Mandela Bay Development Agency, 2014. Projects: Township. Helenvale. http://www.mbda.co.za/ProjectView.aspx?Project=15 Accessed 18 June 2018.

- McCann, J, 1999. Race, protest and public space: Contextualizing Lefebvre in the US city. Antepode 31(2), 163–84.

- Petrus, T, 2013. Social (re)organisation and identity in the ‘Coloured’ street gangs of South Africa. Acta Criminologica 26(1), 71–85.

- Petrus, T, 2014. Policing South Africa’s ganglands: A critique of a paramilitary approach. Acta Criminologica 27(2), 14–24.

- Petrus, T, 2015a. Enemies of the “state”: Vigilantism and street gangs as symbols of resistance in South Africa. Aggression and Violent Behavior 22, 26–32.

- Petrus, T, 2015b. ‘They smoke it, then they go mal [mad] … ’: An anthropological perspective on the drugs-gangs-violence connection and South Africa’s national drug plan. Acta Criminologica Special Edition 3, 180–95.

- Petrus, T, 2017a. From policy to practice: A comparative overview of policies and interventions to curb street gangs in both the international and local contexts. Acta Criminologica 30(2), 65–78.

- Petrus, T, 2017b. Die klipgooiers [The stone-throwers]: Gangsterism and the influence of the stone-throwing subculture in a gang-affected community in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Acta Criminologica 30(5), 38–50.

- Petrus, T, 2018. The dynamics of social development in a coloured community in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Journal of Social Development in Africa 33(2), 111–34.

- Petrus, T & Isaacs-Martin, W, 2012. The multiple meanings of coloured identity in South Africa. Africa Insight 42(1), 87–102.

- Petrus, T & Kinnes, I, 2018. New social bandits? A comparative analysis of gangsterism in the Western Cape and Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa. Criminology and Criminal Justice. doi 10.1177/1748895817750436

- Safety and Peace through Urban Upgrading Inception Report and Masterplan, 2014. Mandela Bay Development Agency, Port Elizabeth.

- Setokoe, T, 2017. ‘We are bringing the army’, News 24, 22 November. https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/Local/PE-Express/we-are-bringing-the-army-20171120 Accessed 18 June 2018.

- Sorokin, P, 1964. Sociocultural causality, space, time. Russell and Russell, New York.

- Spies, D, 2017. Mbalula vows to end gang rule in Nelson Mandela Bay, News 24, 18 November. https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/mbalula-vows-to-end-gang-rule-in-nelson-mandela-bay-20171118 Accessed 18 June 2018.

- Unwin, T, 2000. A waste of space? towards a critique of the social production of space … . Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 25(1), 11–29.

- Wadvalla, BA, 2016. South Africa’s foetal alcohol syndrome problem, Aljazeera, 27 May. http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2016/05/south-africa-foetal-alcohol-syndrome-problem-160505130246555.html Accessed 16 February 2018.

- We Care Project Initiative, n.d. Background. http://www.wecareproject.co.za/index.php Accessed 7 June 2018.

- Western, J, 1982. Outcast Cape Town. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.