?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Rapid urban growth due to unprecedented rural–urban migration is putting pressure on urban food systems. The general impression is that households engaged in urban agriculture experience improved nutritional status, higher health standards and provide towards income and employment. However, empirical research findings are limited and inconsistent. This study provides empirical knowledge on the urban agriculture–food security nexus. Data was gathered from a sample of 220 households comprising of those with small household (backyard) garden projects funded by the Department of Agriculture in the Western Cape, South Africa, and a control group. Propensity score matching was used to determine the contribution of urban agriculture to household food security. The findings indicated that households engaged in urban agriculture were benefiting from dietary diversity and the generation of income through the production of various food products. There was, however, no indication of a significant positive contribution of urban agriculture towards food security.

Highlights

Households engaged in urban agriculture are benefiting in terms of dietary diversity.

There is no significant positive contribution of urban agriculture towards food security in terms of food access, dietary diversity and income.

Urban agriculture, however, has a significantly low positive impact on the total value of food consumed, which is an indication of the availability of energy.

1. Introduction

The twenty-first century has often been dubbed ‘the first urban century’ (Brückner, Citation2012; Stewart et al., Citation2013), characterised by rapid urban growth due to unprecedented rural–urban migration. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat, Citation2011) estimated that 60% of people will reside in urban areas by 2030. The growth and migration of the population in urban areas all over Africa showed a steady increase of about 200 million people since 1990 to approximately 401 million people in 2010 (UN-Habitat, Citation2014). In the 20 year period after 1990, it was estimated that the share of the urban population of Africa, increased with 7% from 32% in to 39%. The anticipation is that this number would rise to 50% in the 2030s (Smit, Citation2016). This will result in increased pressure on urban resources, especially in cities of low- and middle-income countries, which will lead to pressure on urban food security.

There is growing recognition of the need for more holistic interventions to address the looming problem of urban food insecurity (Battersby, Citation2011). According to De Cock et al. (Citation2013), such holistic interventions should allow a better understanding of the scope of the problem, foster improvements of both farming productivity and non-farming incomes, and should be supported by numerous support systems implemented by government, civil society and the private sector (Lemba, Citation2009; D’Haese et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, the thrust of food security policies in sub-Saharan Africa has focused mainly on rural food security, with urban food security as a much neglected phenomenon in development planning and intervention (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Citation2008). This has led to policies and programmes that fail to acknowledge urban food insecurity (Battersby et al., Citation2015). In fact, Crush & Frayne (Citation2010) argued that there has been no systematic attempt to differentiate rural from urban food security, to understand the dimensions and determinants of urban food security, to assess whether the rural policy prescriptions for reducing hunger and malnutrition are workable or even relevant to urban populations. In addition, policies and programmes should be developed to assist in specific food needs, and increase circumstances of the urban poor (Crush & Frayne, Citation2010). These assertions call for increased attention on urban food security research.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the levels of urban food insecurity are high. Affordability of food is often the most important factor in determining food security. This is due to the fact that the majority of urban households depend on purchased food. Generally, when the income level of households are low, food access are the biggest cause of food insecurity, not the availability of food (De Zeeuw & Prain, Citation2011:38). The South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES) (Shisana et al., Citation2013) observed that there are 28% of households at risk of hunger and 26% are experiencing hunger. The equivalent figures in urban informal settlement areas were 32% and 36%, respectively.

Several studies have been conducted in South Africa to assess the role of urban agriculture in contributing towards poverty alleviation and food security (see for example, Burger et al., Citation2009; Cloete et al., Citation2009; Ruysenaar, Citation2013; Battersby et al., Citation2015). The study by Burger et al. (Citation2009) on the role of urban agriculture in alleviating poverty, indicated that urban agriculture was mostly practiced by poor households, mostly female-headed households, and that it was not considered as the main source of income. In addition, households that did not engage in urban agriculture performed better in terms of household assets compared to households that were engaged in urban agriculture; hence, urban agriculture did not contribute significantly to household income. The study by Ruysenaar (Citation2013) that evaluated the impact of an urban agriculture-based programme implemented by the former Gauteng Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Environment, highlighted modest contribution to food security. However, the study called for a need to understand the systems of implementation for urban agricultural projects as a way of providing a holistic understanding of institutional and contextual nature of urban food systems. The study by Cloete et al. (Citation2009) indicated a positive correlation between the period of involvement in urban agriculture and household food security status. Households engaged in urban agriculture for longer periods had lower levels of food insecurity. The study concluded that urban agriculture is an enterprise ‘to which people have recourse once food security comes under threat- hence the higher levels of insecurity in the case of those practitioners who had been involved in UA [urban agriculture] for less than one year’ (Cloete et al., Citation2009:page number). According to Burger et al. (Citation2009), despite an increase in urban agriculture research since the 1990s, the implementation of policy support by African countries has been slow to integrate urban agricultureFootnote1 as a food supply alternative to urban areas due to lack of information and appropriate institutional responses.

Although urban agriculture has increasingly been identified by urban decision-makers and researchers as a highly promising pillar of informal food supply systems (Rogerson, Citation1998; Cofie et al., Citation2003; Mougeot, Citation2005; Paganini et al., Citation2018), the evidence of its impact on urban food security is still highly anecdotal and contested. For example, Stewart et al. (Citation2013) considered early studies as generalisations, such as those of Wayburn (Citation1985) and Rogerson (Citation1998) that supported the contribution of urban agriculture to urban food security. A study by Schmidt & Vorster (Citation1995) could not find a link between food gardens and nutritional security and no significant difference could be found between farming and non-farming households concerning nutritional status. Van Averbeke (Citation2007) reported that the contribution of urban agriculture to total household income and food security in the informal settlements of Atteridgeville near Pretoria in South Africa were mostly modest; however, it was argued that urban agriculture contributed to a better livelihood status in the study group. Ellis & Sumberg (Citation1998:221) argued that urban agriculture both claimed too much and offered too little in the policy context of urban poverty and family food security. They argued that it claimed too much by equating all food production in towns with improved food security for poor people, and offered too little by failing to consider the role of rural–urban interactions in explaining the survival capabilities of the urban poor. Webb (Citation2000) questioned the evidence for the positive nutritional impact of urban agriculture on the diets of the poor. More recently, scepticism has increasingly characterised discussion about the extent, impact and potential of food production by the poor in Southern Africa’s urban areas (Crush et al., Citation2011). Thornton (Citation2012) claimed that it has become necessary to debate the efficiency of urban agriculture in improving the livelihoods of poor urban households.

In recognition of these contestations, this study aimed at providing empirical findings on the urban agriculture–food security nexus through a case study of urban agriculture in the Western Cape province of South Africa. The Western Cape Department of Agriculture in South Africa has implemented many urban agricultural initiatives in the informal settlement areas of the Cape Town Metropole. The Department’s extension division is responsible for advice and other extension services to the beneficiaries of these initiatives that include urban household and community food gardens. The purpose of this article is to determine the significance of urban agriculture in addressing household food insecurity among lower income groups in selected informal settlement areas of the Cape Town Metropole.

2. Conceptual framework

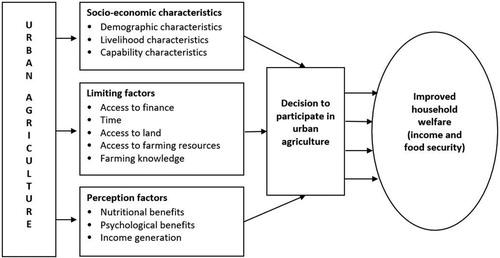

This study adopted a conceptual framework from Gamhewage et al. (Citation2015). The decision to participate in urban agriculture is affected by three categories of factors. These factors include socio-economic factors, perception on urban agriculture, and the constraints which hinder the efforts to participate (). The socio-economic factors influence the availability of resources such as human resources, time, investments, access to land area (space for urban agriculture) and practical knowledge of urban agriculture. The socio-economic factors are influenced by demographic characteristics, livelihood characteristics and capability characteristics (Swanepoel et al., Citation2017). Some limiting factors that may act as barriers for households to enter into urban agriculture include access to finance, time, access to land and farming resources, and knowledge of farming. Participation is also influenced by some perceptual factors, such as the nutritional and psychological benefits as well as income generation. When the socio-economic factors are in positive conditions, they stimulate the participation in urban agriculture; but in contrast, if the factors are negative, they can act as barriers for engagement (Gamhewage et al., Citation201Citation5). The perceptions on the importance of urban agriculture vary among individuals. For example, according to Adebisi & Monisola (Citation2012), the main reasons for women in Nigeria to enter into urban agriculture include food security, supplementing income and accessibility to land. Jongwe (Citation2014) indicated that production for home consumption, to cover some food shortages and income enhancement, are the main reasons for households to take up urban agriculture.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for participation in urban agriculture (adapted from Gamhewage et al. Citation2015).

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection

The study was conducted in the informal settlement areas in the Cape Town Metropole of the Western Cape province in South Africa. The areas covered by the study were Kraaifontein, Khayelitsha, Philippi, Mitchell’s Plain, Bonteheuwel and Guguletu. These areas house some of the poorest communities in the Cape Town Metropole. The study population comprised households in these informal settlement areas involved in urban agricultural activities. These households formed part of the Farmer Support and Development programme of the Department of Agriculture in the Western Cape and included household food gardening projects. Assistance included funding and extension services. A purposive sampling method was applied. The sample was implicitly selected (thus identified and referred by the Western Cape Department of Agriculture) to be a representative sample to meet the aims of the research. This sampling group consisted of households that benefited from government-funded household food garden projects. A total of 220 households were selected, of which 154 were farming households and 66 non-farming households. Non-farming households were selected through random sampling. The purpose of this sampling method was to select an unbiased representation of the total population.

By means of structured questionnaires, quantitative data were obtained. Questions included households’ social characteristics, households’ food security information based on different food security indicators, income and expenditure information, as well as methods households produce food and the types of food produced, access to water, markets and government support programmes. The data collected contributed to a thorough analysis of the social and economic aspects of food security at household level. Furthermore, the indicators affecting food security at household level were identified by including the four main components of food security. These include food availability, accessibility, utilisation and food stability.

3.2. Data analysis

3.2.1. Propensity score matching

Matched comparison evaluation techniques are the most researched methods of evaluation methodology. According to Baker (Citation2000), this is one of the best quasi-experimental design techniques to use as an alternative towards experimental design. Rosenbaum & Rubin (Citation1983) defined the propensity score as the conditional probability of receiving a treatment, given pre-treatment observable characteristics. It is thus a model used to predict the probability of an event occurring.

The propensity score matching method was used to determine the contribution of urban agriculture on household food security. According to Randolph et al. (Citation2014), the attributing outcomes to programme interventions are often challenging since difficulties are experienced in observing the outcome in counterfactual and treatment situations. In this study, propensity score matching reduced selection bias and strengthened causal conclusions.

Another reason for selecting the propensity score matching method was the lack of historical data on the control group. Therefore, the econometric model was used to estimate the effect of urban farming on income and food security of the households experiencing food insecurity. A statistical counter-factual group was thus created based on the probability that the group would contribute to urban agriculture by using the observed household characteristics.

The validity of this method, however, depended on the provisional independence and overlap in propensity scores across the treated and control group, while propensity score matching depends on both the number of variables required to estimate participation and outcomes, as well as in the number of participants and non-participants entering the matching process (Bryson et al., Citation2002). Therefore, the results based on small samples of non-participants should be interpreted cautiously. However, studies by Bryson et al. (Citation2002) showed that even though the propensity score matching method requires data to show good matches, efficient small samples can be analysed sufficiently where single treatment is being evaluated.

3.2.2. Model specification and estimation

The first step in propensity score matching was to make an estimation regarding the probability of participation of urban agriculture – the decision to participate in urban agriculture as outlined in . This was done by means of the Probit model, which in turn is required to estimate the propensity scores. Borrowing from Heinrich et al. (Citation2010), the Probit model is identified as follows:

(1)

(1) The particular pre-treatment household characteristics that influence urban farming determines the conditional probability of participation; these include socio-economic characteristics, limiting factors and perception factors as outlined in .

Where D = (0, 1) indicator of participation in urban agriculture; X = vector of pre-participation household characteristics.

According to a study by Swanepoel et al. (Citation2018), the following most important household characteristics showing significance were included in the analysis:

Access to land (sufficient area to produce).

Gender of household head.

Distance from selling markets (where produce would be sold – measured in travelling time from house to market).

Where D=1, a household would participate in urban agriculture, and where D=0, the household would not participate in urban agriculture. The smaller number of conditional variables provided outcomes that were more robust.

When propensity scores were measured, matching was done by using methods as suggested by Heinrich et al. (Citation2010), namely nearest neighbour matching, kernel matching, and stratification matching algorithms. Y1 (D1) then defined the most likely outcomes for the total population. The treatment effect on the total population is expressed as:

(2)

(2) It was not possible to determine the effect of an individual treatment since it would produce only one possible outcome; the focus was therefore on average impact (Heinrich et al. Citation2010). The main purpose of this analysis was to determine the Average Treatment effect on the Treated (ATT), namely the display of the outcome of contribution of urban agriculture towards food security and income. This analysis therefore showed the difference in outcome between households involved in urban agriculture and households not involved in urban agriculture. Heinrich et al. (Citation2010) defined this analysis as:

(3)

(3) Where Υ1 = income per month or food security outcomes for households involved in urban agriculture; Υ0 = the situation for households not involved in urban agriculture.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Urban agriculture production levels

This study showed significant differences between male- and female-headed households for the production of maize, with maize production was dominated by male-headed farmers. Spinach was mostly produced by female-headed farmers, while other leafy vegetables where mostly produced by male-headed farmers (). The reason for the dominance in maize production by male-headed households might be due to its production effort. From it is clear that spinach was the most popular agricultural product produced by 29.3% and 39.7% of male- and female-headed households, respectively. Cabbages, onions and carrots were other agricultural products produced by more than 20% of both male- and female-headed households. More than 10% of male- and female-headed households reported to produce potatoes, beans and tomatoes. It is thus clear that the majority of households in the informal settlement area of the Cape Town Metropole produced vegetables, while 11% of male-headed households also produced maize. Only one percent of the households in the study produced fruit, and bred livestock and poultry.

Table 1. Urban agriculture production levels.

4.2. Food security indicators

shows the farming status (non-farming or farming) of households for the food security indicators. No significant difference could be observed between farming and non-farming households for any of the food security indicators. The analysis showed that non-farming households were more food secure than the farming households. Values of respectively 14.05 and 13.52, were observed respectively on the household food insecurity access scale. Furthermore, more than 75% of the households of farming and non-farming households experience severe food insecurity, with a higher percentage of farming households experiencing severe food insecurity.

Table 2. Household farming status by food security indicators.

No significant difference could be observed when looking at the household diet diversity score (HDDS). The level of diet diversity for farming households measured a little higher (10.4) than the non-farming households (10.3). Similar findings were made by the Western Cape Department of Agriculture (Citation2015), which reported that households participating in the production of food mostly showed higher diet diversity.

On average, non-farming households spent R286.35 on food consumed per month, while R359.35 per month is spent by farming households. Even though households involved in farming spend R70.00 less on food consumed per month, no significant difference could be seen between the different types of households. Similar results were evident for the share of household income spent by farming (51%) and non-farming households (47%). Furthermore also shows an average income of R3 690.00 for non-farmering households, while the average income of farming households are R3 486.47 per month.

According to , only 35.7% of urban farmers earned more than US$2 per capita per day, while this was the case for 45.5% of non-farmers. Similar observations were evident for the US$1.25 income per capita level for non- and urban farmers. There was no significant difference observed for farming type (Swanepoel & van Niekerk, Citation2018).

Table 3. Levels of per capita income per day in US$ in the different informal settlement areas of the Cape Town Metropole.

4.3. Propensity score matching

Three variables were identified to estimate propensity scores to include in the analysis, namely the gender of the household head, access to land and distance to markets. These variables were selected based on results obtained from a study conducted by Swanepoel et al. (Citation2018) on the informal settlement areas and urban farming in the city of Cape Town Metropole.

Even though household income may influence the household’s decision to include urban farming as alternative means to contribute to the household’s diet, income or food security situation, the variable was not included in the propensity score matching analysis due its independent nature. The factors that would have an influence on the likelihood for households to be participating in agriculture were identified by means of the Probit regression analysis.

The results from the Probit regression analysis are presented in . Consequently, the gender of the household head, distance from the markets and access to land proved to be significant determinants for households to participate in agricultural production.

Table 4. Likelihood of participating in urban agriculture (Probit Model).

4.4. Average treatment of participating in urban agriculture

shows the average treatment effects on the untreated (ATT) of participating in urban agriculture on income and food security outcomes by using the propensity scores and identification of indicators of the urban agricultural impact. The ATT analysis was done in STATA 11 based on a number of matching techniques. Since access to land, gender of household head and distance to markets were found to significantly affect the likelihood to participating in urban agriculture in the Probit model, these three factors were therefore used as conditional variables. The common support region and balancing property was satisfied.

Table 5. Average treatment effect on the treated (participating in urban agriculture) using nearest neighbours, stratification and radius matching methods.

From the results in , it is clear that participating in urban farming has a significant positive effect on total value of food consumption (TVC) (financial value of food consumed) in all estimations. Significance was found, especially on TVC ranging from R78.00 to R88.06 per capita per month. From this result, it can be concluded that urban farming does improve food availability and food access among households. It is nonetheless important to note that the TVC does not involve the diet diversity or nutritional value of the food consumed by the household. More so, the size of effect is very low, given the high food prices in South Africa (National Agricultural Marketing Council, Citation2015).

further shows that urban agriculture had a negative effect on the household food insecurity access scale, and consequently there was no significance, as well for the kernel, stratification and near neighbour techniques. The analysis of the effect of urban agriculture on the HDDS showed a positive effect, but also had no significant influence on the three estimations. From the above results, it can be concluded that urban agriculture does not contribute significantly to the accessibility and nutritional diversity of household food security in the informal settlement areas of the Cape Town Metropole.

Although some researchers encouraged urban agriculture as a means to contribute meaningfully to food security (see, for example, Schmidt & Vorster, Citation1995; Maxwell et al., Citation1998), the findings in this study showed otherwise. The fact that this study showed that urban agriculture did not significantly improve household food security and diet diversity in the informal settlement areas of the Cape Town Metropole, are supported by other researchers, including Schmidt & Vorster (Citation1995) (Slough, North West province); Van Averbeke (Citation2007) (among the informal settlements of Atteridgeville, Gauteng province); Aliber & Hart (Citation2009) (Limpopo province), Burger et al. (Citation2009) (role of agriculture in poverty alleviation in South Africa) and Battersby (Citation2011) (informal settlements of the Cape Town Metropole).

The effect of urban agriculture on monthly household income per capita was positive but not significant for all three tests. For the three matching techniques, monthly household income per capita ranged from R61.00, R52.91 and R182.18 for the stratification, kernel and nearest neighbour techniques, respectively. These values were very low in relation to that of other studies. This finding is inconsistent from the views accorded to urban agriculture in most large cities of Africa (Zezza & Tasciotti, Citation2010). This concludes that the impact of urban agriculture is still very low on income for the poor.

It is also noteworthy that urban agriculture has a positive effect on the total share of expenditure. This means that urban agriculture has negatively affected the share of spending on total expenditure. Significance was found with all three matching techniques. The results of these analyses are a clear indication that urban agriculture does not significantly contribute to income. According to research by Frayne et al. (Citation2014), it was found that in 2008, 77% of households engaged in urban agriculture in 11 cities in Southern Africa reported conditions of food insecurity. However, given the high food price and inflation in South Africa (National Agricultural Marketing Council, Citation2015), it could be that the marginal effect on income has been outstripped by price changes. Nevertheless, this argument can be verified with further investigation on income and food prices.

5. Conclusion

Although the literature shows contradicting results regarding the contribution of urban agriculture to household food security, it is important to keep in mind that methods of measurement differ, and cities also differ regarding their urban agricultural characteristics. In addition, different policy approaches are adapted and assistance towards urban agriculture also differs. The results furthermore indicate that urban farming households benefit to a certain extent in terms of diet diversity due to the production of different food groups produced. There is, however, no indication of a significant positive contribution of urban agriculture towards household food security in terms of food access and income. Urban agriculture does, however, have a significantly low positive impact on total value of food consumed. It is therefore concluded that the household gardens in the sample group were not contributing significantly to household food security.

6. Policy implications

Policy and support towards urban agriculture in South Africa and the Western Cape province were thoroughly discussed in the past, but further discussions and research are necessary towards land distribution, land utilisation, optimisation of land, analysis of urban farming constraints, measurement of food security and educating urban farmers (Webb, Citation2011; Drimie, Citation2016). Institutionalised support for urban farmers should be carefully considered. Governmental policymakers need to awaken to the fact that substantial investment in urban farming is not always viable due to a lack in sustainability. It is therefore advisable that more research should be conducted on sustainable urban agricultural systems on household level and production of high-valued produce on small areas. Furthermore, job creation should be one of the key focal points in urban informal settlement areas to reduce poverty and enable households to access food.

Author contribution

The main author, Dr Swanepoel, conducted this study as part of his doctoral thesis; thus, he did the data collection, data analysis and writing of the article. Dr Van Niekerk assisted in his capacity as supervisor and editing of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 In this paper, urban agriculture follows a definition by Thornton (2008), who referred to ‘any agriculturally-related activities, which include production, processing and marketing, occurring in built-up “intra-urban” areas and in the “peri-urban” fringes (often “green belts”) of cities and towns’.

References

- Adebisi, A & Monisola, TA, 2012. Motivations for women involvement in urban agriculture in Nigeria. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development 2(3), 337–43. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.197979

- Aliber, M & Hart, TGB, 2009. Should subsistence agriculture be supported as a strategy to address rural food security? Agrekon 48(4), 434–58. doi:10.1080/03031853.2009.9523835

- Baker, JL, 2000. Evaluating the impact of development projects on poverty: a handbook for practitioners. Directions for development. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/13949

- Battersby, J, 2011. The state of urban food insecurity in Cape Town. Urban Food Security Series No. 11. Kingston and Cape Town: Queens’ University and AFSUN. http://www.afsun.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/AFSUN_11.pdf Accessed 4 January 2021.

- Battersby, J, Haysom, G, Marshak, M, Kroll, F & Tawodzera, G, 2015. Looking beyond urban agriculture. Extending urban food policy responses. Policy Brief, South African Cities Network. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1668.7441

- Brückner, M, 2012. Economic growth, size of the agricultural sector, and urbanization in Africa. Journal of Urban Economics 71(1), 26–36. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2011.08.004

- Bryson, A, Dorsett, R & Purdon, S, 2002. The use of propensity score matching in the evaluation of active labour market policies. Working Paper No. 4. London: Department for Works and Pensions. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/4993

- Burger, P, Geldenhuys, JP, Cloete, J, Marais, L & Thornton, A, 2009. Assessing the role of urban agriculture in addressing poverty in South Africa. Global Development Network (GDN) Working Paper Series. Working Paper No. 28, October 2009.

- Cloete, J, Lenka, M, Marais, L & Venter, A, 2009. The role of urban agriculture in addressing household poverty and food security: The case of South Africa. Global Development Network (GDN) Working Paper No. 15, September 2009.

- Cofie, OO, Van Veenhuizen, R & Drechsel, P, 2003. Contribution of urban and peri-urban agriculture to food security in Sub-Saharan Africa. IWMI-ETC paper presented at the 3rd WWF, 17 March, Kyoto.

- Crush, J & Frayne, B, 2010. The invisible crisis: Urban food security in Southern Africa. Urban Food Security Series No. 1. Queen’s University and AFSUN: Kingston and Cape Town.

- Crush, J, Hovorka, A & Tevera, D, 2011. Food security in Southern African cities: The place of urban agriculture. Progress in Development Studies 11(4), 285–305. doi:10.1177%2F146499341001100402

- De Cock, N, D’Haese, M, Vink, N, Van Rooyen, CJ, Staelens, L, Schönfeldt, HC & D’Haese, L, 2013. Food security in rural areas of Limpopo province, South Africa. Food Security 5(2), 269–82. doi:10.1007/s12571-013-0247-y

- D’Haese, L, Vasile, M & Romo, L, 2013. Research project “Rajah Grow Together” food security in Ekurhuleni, Gauteng Province, South Africa, 1–123. Independent study.

- De Zeeuw, H & Prain, G, 2011. Effects of the global financial crisis and food price hikes of 2007/2008 on the food security of poor urban households. Urban Agriculture Magazine 25, 36–38.

- Drimie, S, 2016. Understanding South African food and agricultural policy: Implications for agri-food value chains, regulation, and formal and informal livelihoods (August). http://www.plaas.org.za/sites/default/files/publications-pdf/WP39Drimie_0.pdf Accessed 4 February 2017.

- Ellis, F & Sumberg, J, 1998. Food production, urban areas and policy responses. World Development 26(2), 213–25. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10042-0

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2008. The state of food insecurity in the world 2008: High food prices and food security – Threats and opportunities. Rome.

- Frayne, B, Mccordic, C & Shilomboleni, H, 2014. Growing out of poverty: does urban agriculture contribute to household food security in Southern African cities? Urban Forum 25, 177–89. doi:10.1007/s12132-014-9219-3

- Gamhewage, MI, Sivashankar, P, Mahaliyanaarachchi, RP, Wijeratne, AW & Hettiarachchi, IC, 2015. Women participation in urban agriculture and its influence on family economy – Sri Lankan experience. Journal of Agricultural Sciences 10(3), 192–206. doi:10.4038/jas.v10i3.8072

- Heinrich, C, Maffioli, A & Vázquez, G, 2010. A primer for applying propensity-score matching: Impact-evaluation guidelines. Technical notes, No. IDB-TN-161 (August), 1–56. Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/A-Primer-for-Applying-Propensity-Score-Matching.pdf Accessed 5 January 2021.

- Jongwe, A, 2014. Synergies between urban agriculture and urban household food security in Gweru City, Zimbabwe. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics 6(2), 59–66. doi:10.5897/JDAE2013.0506

- Lemba, J, 2009. Intervention model for sustainable food security in the drylands of Kenya: case study of Makueni district. Doctoral thesis, Universiteit Gent. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-715892

- Maxwell, D, Levin, C & Csete, J, 1998. Does urban agriculture help prevent malnutrition? Evidence from Kampala. Food Policy 23(5), 411–24. doi:10.1016/S0306-9192(98)00047-5

- Mougeot, LJA, 2005. Agropolis. The social, political and environmental dimensions of urban agriculture. IDRC, London.

- National Agricultural Marketing Council, 2015. Food price monitor, Issue 2015/February. Markets and Economic Research Centre. https://www.namc.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/NAMC-Food-Price-Monitor-February-2015.pdf Accessed 5 January 2021.

- Paganini, N, Lemke, S & Raimundo, I, 2018. The potential of urban agriculture towards a more sustainable urban food system in food-insecure neighbourhoods in Cape Town and Maputo. Economia Agro-Alimentare/Food Economy 20(3), 399–421. doi:10.3280/ECAG2018-003008

- Randolph, JJ, Falbe, K, Manuel, AK & Balloun, JL, 2014. A step-by-step guide to propensity score matching in R. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation 19(18), 1–6. http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=19&n=18 Accessed 4 January 2021.

- Rogerson, CM, 1998. Urban agriculture and urban alleviation. South African Debates 37(2), 171–88. doi:10.1080/03031853.1998.9523503

- Rosenbaum, PR & Rubin, DB, 1983. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1), 41–55. doi:10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

- Ruysenaar, S, 2013. Reconsidering the ‘Letsema principle’ and the role of community gardens in food security: evidence from Gauteng, South Africa. Urban Forum 24, 219–49. doi:10.1007/s12132-012-9158-9

- Schmidt, MI & Vorster, HH, 1995. The effect of communal vegetable gardens on nutritional status. Development Southern Africa 12(5), 713–24. doi:10.1080/03768359508439851

- Shisana, O, Labadarios, D, Rehle, T, Simbayi, L, Zuma, K, Dhansay, A, Reddy, P, Parker, W, Hoosain, E, Naidoo, P, Hongoro, C, Mchiza, Z, Steyn, NP, Dwane, N, Makoae, M, Maluleke, T, Ramlagan, S, Zungu, N, Evans, MG, Jacobs, L, Faber, M & SANHANES-1 Team, 2013. South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1). HSRC Press, Cape Town. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageNews/72/SANHANES-launch%20edition%20%28online%20version%29.pdf Accessed 5 January 2021.

- Smit, W, 2016. Urban governance and urban food systems in Africa: examining the linkages. Cities 58, 80–86. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.05.001

- Stewart, R, Korth, M, Langer, L, Rafferty, S, Rebelo da Silva, M & Van Rooyen, C, 2013. What are the impacts of urban agriculture programs on food security in low and middle-income countries? Environmental Evidence 2, 7. doi:10.1186/2047-2382-2-7

- Swanepoel, JW & Van Niekerk, JA, 2018. The level of household food security of urban farming and non-farming households in the informal settlement area of the Cape Town Metropole in South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 46(2), 89–106. doi:10.17159/2413-3221/2018/v46n2a468

- Swanepoel, JW, Van Niekerk, JA & D’Haese, LS, 2017. The socio-economic profile of urban farming and non-farming households in the informal settlement area of the Cape Town metropole in South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 45(1), 131–40. doi:10.17159/2413-3221/2017/v45n1a447

- Swanepoel, JW, Van Niekerk, JA & Van Rooyen, CJ, 2018. An analysis of the indicators affecting urban household food insecurity in the informal settlement area of the Cape Town metropole. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 46(1), 113–29. doi:10.17159/2413-3221/2018/v46n1a467

- Thornton, AC, 2012. Urban agriculture in South Africa: a study of the Eastern Cape province. Edwin Mellen Press, New York.

- UN-Habitat (United Nations Human Settlements Programme), 2011. Third United Nations conference on housing and sustainable urban development (Habitat III), 44813 (August). https://unhabitat.org/habitat-iii

- UN-Habitat (United Nations Human Settlements Programme), 2014. The state of African cities 2014: Re-imagining sustainable urban transitions. Nairobi, Kenya. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/State%20of%20African%20Cities%202014.pdf

- Van Averbeke, W, 2007. Urban farming in the informal settlements of Atteridgeville, Pretoria, South Africa. Water SA 33(3), 337–42. (special edition) doi:10.4314/wsa.v33i3.49112

- Wayburn, L, 1985. Urban gardens: a lifeline for cities? The Urban Edge 9, 4–5.

- Webb, N, 2000. Food-gardens and nutrition: three Southern African case studies. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences 28, 62–7. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jfecs/article/download/52792/41393 Accessed 5 January 2021.

- Webb, NL, 2011. When is enough, enough? Advocacy, evidence and criticism in the field of urban agriculture in South Africa. Development Southern Africa 28(2), 195–208. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2011.570067

- Western Cape Department of Agriculture, 2015. Impact evaluation of the food security programme on household food security in the Western Cape. https://www.elsenburg.com/sites/default/files/Food%20security_0.pdf Accessed 1 February 2016.

- Zezza, A & Tasciotti, L, 2010. Urban agriculture, poverty, and food security: empirical evidence from a sample of developing countries. Food Policy 35(4), 265–73. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.04.007