ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to evaluate South Africa’s implementation of educational Information and Communication Technology (ICT), which is led by Gauteng and the Western Cape Provinces, for participation in the global knowledge economy. Accordingly, the two provinces are in the forefront of educational ICT implementation aimed at preparing learners for participation in the global knowledge economy and national development. The paper uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to examine South Africa in comparison with fourteen developing countries to establish that its approach towards implementation of educational technology is not appropriate, sustainable nor effective for a developing country. Experiences of developing countries such as Vietnam, Zambia and Kenya, which are in the medium and low Human Development Index (HDI) categories, show that national technological cultures of people have not evolved into what is characterised as the ‘Net Natives’, which is one of the primary driving force for the adoption of blended pedagogies as an approach for implementing educational technology, to enhance participation in the global knowledge economy.

1. Introduction

South Africa is one of the countries with an emerging economy and yet, the highest ranked in development among African countries (Hart & Laher, Citation2015). Its position in Africa is partly explicable through its ICT infrastructure, which is supposed to create the opportunities for its competitive entry into the global knowledge economy (Mayisela, Citation2013; Farrukh & Singh, Citation2014; Hart & Laher, Citation2015). Accordingly, ‘technology has become so much part of our lives in the twenty-first century that even being fully literate now includes an aspect of computer literacy’ (Mayisela, Citation2013:1). South Africa, just like other developing countries, is focused on reducing the ‘digital divide’ among its population by using ICT for societal empowerment and transformation (Hart & Laher, Citation2015). According to Mayisela (Citation2013:2), digital divide is defined as ‘as any unequal information and communication technology (ICT) access pattern among populations’. Additionally, Fink and Kenny (2003:2 cited in Mayisela, Citation2013:2) describe digital divide as gaps in access to use of ICTs, ability to and actual use of ICTs and impact of its use. To realise its dream, South Africa’s White Paper on e-Education provides that all teachers and learners be ICT-capable by 2013 (Department of Education, Citation2004). This admirable goal is however not yet achieved seven years after the target date. Accordingly, one of the major reasons for not achieving this goal was mostly due to the ‘techno-determinist’ view largely adopted by the government, which prioritise access to ICT infrastructure and consider it to be sufficient for creating, encouraging and supporting the development of digital skills (Mayisela, Citation2013; Hart & Laher, Citation2015). Evidently, the adoption of educational ICT goes beyond mere access of infrastructure and online material (Farrukh & Singh, Citation2014; Hart & Laher, Citation2015).

ICT has the capacity to transform education positively through its support of collaborative, creative, innovative, adaptable and flexible teaching and learning that develop the twenty-first-century skills (Peeraer & Van Petegem, Citation2015; Ramoroka & Tsheola, Citation2016; Ramoroka et al., Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c; Akyuz, Citation2018; Han et al., Citation2019). The purpose of the paper is to evaluate South Africa’s implementation of educational ICT lead by Gauteng and the Western Cape provinces for the nation’s competitive participation in the global knowledge economy. The paper consists of six sections including this introduction and the conclusion. The second section presents the research methodology adopted in this paper. The third and fourth sections present the theoretical perspective which specifically focuses on the principles and international experiences with a focus on some of the 14 selected which will be compared with South Africa. The fifth section discusses the processes of blended pedagogies for E-learning as well as E-learning experiences from Gauteng and the Western Cape Provinces. The sixth section presents the findings of the paper and further provides a critical analysis of the findings. The last section concludes that, like many other countries, South Africa’s educational ICT infrastructure may present an appearance of being appropriate but, its planning approaches, governance models, teachers’ and learners’ skills and e-culture should be questioned for successful, sustainable and effective implementation of a totally blended pedagogic environment.

2. Research methodology

Similarly to Tsheola et al. (Citation2017), this paper conveniently sampled a total number of 15 countries which include South Africa, with a representation of the four Human Development Index (HDI) categories (‘very high’, ‘high’, ‘medium’ and ‘low’), which were determined in the 2015 United Nations Development Programme. Collectively, the 15 countries with 28 variables with a focus on planning, governance, socio-economic environment, knowledge economy and connectivity were selected for Principal Component Analysis (PCA). There are previous applications of human development variables for studying experimentations with blended learning and preconditions thereof, inclusive of planning, governance, infrastructure, skills and culture, using multivariate, factor or component analysis techniques (Webster & Son, Citation2015; Domingo & Garganté, Citation2016; Hung, Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2016; Ramoroka & Tsheola, Citation2016; Salminen et al., Citation2016; Ramoroka et al., Citation2016a, Citation2016b). In isolation, specific human development indicators are not definitive of the concept of blended learning (Domingo & Garganté, Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2016; Salminen et al., Citation2016; Ramoroka et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c). Therefore, the complexity of the process of assigning geographic units to places along the HDI levels requires analysis of interrelationships among variables that entails application of multivariate techniques. The next section discusses the principles and processes of blended pedagogies for e-learning.

3. Blended pedagogies for e-learning: principles and processes

Conventional didactics involve traditional techniques and procedures of learning wherein learners are passive recipients of information whilst teachers profess all knowledge. In practice, learners acquire knowledge in various ways, inclusive of hearing and seeing, acting and reflecting, logical reasoning, drawing and intuitively, among others, which entail a variety of teaching methods (Valtonen et al., Citation2015; Ramoroka & Tsheola, Citation2016; Salminen et al., Citation2016; Akyuz, Citation2018; Han et al., Citation2019). Seemingly, popular conventional didactics offer the levels and standards of education that provide learners with limited opportunities to compete in the global knowledge economy (Pruet, Ang, & Farzin, Citation2016). That is, the intellectual capabilities needed for participation in the global knowledge economy cannot be acquired through conventional didactics alone (Peeraer & Van Petegem, Citation2015; Valtonen et al., Citation2015; Ramoroka et al., Citation2016b). The latter causes learners’ boredom and distraction in class, poor assessment performance and increased school dropout (Gu et al., Citation2015; Wolff et al., Citation2015; Akyuz, Citation2018; Han et al., Citation2019). However, there is no call for complete replacement of conventional didactics with the digital pedagogies.

Discourse on effective teaching and learning has increasingly been captivated by the didactics of passive versus active learning (Wolff et al., Citation2015; Salminen et al., Citation2016). The traditional teachers’ delivery of information to learners is criticised for reinforcing passive learning and suboptimal knowledge acquisition (Gu et al., Citation2015) because learners ‘do not retain a significant portion of what is taught during lectures’ (Wolff et al., Citation2015:1). Learners using e-learning have been likely to achieve higher grades than those who rely solely on the face-to-face didactic model alone (Gu et al., Citation2015; Salminen et al., Citation2016; Ramoroka et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017c). Extremes of arguments include, on one hand, ‘insinuations that computers are essentially incompatible with teaching’, whilst at the other end some studies affirm that ICT improves knowledge acquisition (Schmidt et al., 2014:286 cited in Webster & Son, Citation2015:85). According to Suh (2004:1040 cited in Webster & Son, Citation2015:85), the question of how to integrate digital technology in teaching and learning for national development is one of the ‘major challenges facing educational policy in the information age’. Using conventional didactics or e-learning alone would not equip learners with the required knowledge and skills; however, blending of the two approaches holds potential for effective and active knowledge acquisition, preparedness for participation in the global knowledge economy and promotion of national development (Peeraer & Van Petegem, Citation2015; Valtonen et al., Citation2015; Salminen et al., Citation2016; Akyuz, Citation2018; Han et al., Citation2019).

Blended learning involves rich technological content that promotes and supports interactivity, creativity, flexibility and collaboration between learners and teachers in order to bring knowledge shared through conventional didactics to life (Hung, Citation2016). Therefore, e-learning should not be seen as an alternative knowledge transfer and acquisition method to conventional didactics. As Park et al. (Citation2016:1) put it, ‘Blended learning is recognised as one of the major trends in higher education today’. Blended learning is more than a mere act of teachers transferring course content into the learning management system and using basic features which include posting the course content and uploading lecturer notes and/or slides (Hung, Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2016; Ramoroka et al., Citation2017c). It is deeply involved; and, it requires clarity of understanding of the instructional interventions adopted, sometimes at an institutional scale, as well as the approaches and support mechanisms for leveraging the various features of learning management system for blended learning (Hung, Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2016; Akyuz, Citation2018; Han et al., Citation2019). To this extent, national frameworks are critical to successful implementation of blended pedagogies. International experiences with a focus on some of the 14 selected which will be compared with South Africa are discussed in the next section.

4. International experiences: synopsis of the selected countries

International illustrations for appropriateness of planning approaches and infrastructure use experiences from 5 countries across the HDI categories. The countries include the Republic of Korea with very high HDI, Thailand with high HDI, Vietnam and Zambia with medium HDI, and, Kenya with low HDI (Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). In South Korea, Webster & Son (Citation2015), conducted a study aimed at ‘discovering the insights into teachers’ decision-making related to consideration of technology use’ (cited in Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b:27). More often than not, teachers were challenged in the application of technological skills acquired from their education, training and experience (Webster & Son, Citation2015; Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). Instead, teachers were ‘doing what works rather than what they knew works best’ (Webster & Son, Citation2015 cited in Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). Generally, Thailand’s ICT infrastructure is developing at a stable pace although its level of quality is not satisfactory enough to fulfil the needs of the population (Pruet et al., Citation2016; Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). With its ICT infrastructure, Thailand has also managed to train more than half of its teachers’ population in e-learning (Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). Observing the future trend of e-learning, the Thais intend to adopt advanced technology to respond to the digital divide (Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). For successful implementation of blended learning in Vietnam, it was very important to target the learning management system in all higher education institutions, provide digital resources to both teachers and learners through an online portal as well as to reduce the digital divide between the poor rural and well-developed urban schools (Peeraer & Van Petegem, Citation2015). Planning and policy development are the most critical; therefore, the Vietnam national policy and plan for technology in education should be consistent with the national vision for ICT in pedagogy and that it be sealed with a definite financial plan.

In Zambia, lack of institutional and sectoral policies on the integration of ICT into education and training is still a challenge regardless of the development and adoption of a national ICT policy as well as an adaptive model that has been adopted for the governance of this educational ICT (Annie et al., Citation2015; Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). This lack of policies suggests a non-existence of ICT competency framework which is at the centre of ensuring technological changes in education and training for both teachers and learners (Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). In practice, the integration of e-learning with conventional didactics by Kenyan teachers has not yet been realised in the classrooms (Nyagowa et al., Citation2013; Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). Although teachers were trained to integrate ICT in their teaching and learning activities, they still fail to use the technology as expected in the existing curriculum (Nyagowa et al., Citation2013; Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). Therefore, to successfully implement blended learning the availability and accessibility of infrastructure as well as teachers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge must first be developed (Ramoroka et al., Citation2017b). Overall, the slow pace of the adoption of blended learning reflects at most, the inappropriateness of the planning approaches and limited infrastructure provided. South Africa’s experiences with a focus on Gauteng and Western Cape Provinces are discussed in the succeeding section.

5. Experiences from Gauteng and the Western Cape Provinces

From the early 2000, South Africa’s revised school curriculum supported an ‘inquiry-based approach’ to learning that encourages learners to ‘explore objects, situations and events in their immediate environment, to collect data and record information and draw conclusions accurately’ (Department of Education, Citation2002:34). As a response to the need for integrating ICT in pedagogy, the Department of Education (Citation2004) set ‘ambitious’ targets that should have been achieved by 2013. Two of the targets are that ‘all schools will have access to a networked computer facility for teaching and learning, and to high quality educational resources’; and, ‘all schools, teachers and learners will be confident and competent users of ICT, and ICTs will be integrated into teaching and learning at all schools’ (Bialobrzeska & Cohen, Citation2005:14 cited in Ramoroka & Tsheola, Citation2015). South Africa’s education system had hoped to develop learners’ skills needed to identify and solve problems; make decisions in a critical, innovative, creative and collaborative way of thinking; collecting, analysing, organising and critically evaluating information and knowledge using technology effectively (Department of Basic Education, Citation2011). Gauteng and Western Cape Provinces responded by taking a lead in the implementation of educational ICT and their experiences are important for the purposes of this paper, and they are briefly reviewed hereunder for illustration of the educational digital technologies rush.

5.1. Gauteng Province schools going ‘paperless’

Gauteng Province started by introducing ICT in June 2013 among ‘school principals, district cluster and circuit leaders, human resource management officials, and curriculum officials, district and head office officials’ for better, improved and strengthened communication between and among these various personnel (Jacobs, Citation2013; Gauteng Department of Education, Citation2014). A total number of 2600 principals, district cluster and circuit leaders, human resource management and curriculum officials as well as district and head office officials were given Samsung Tablets in addition to 2200 Blackberry Smartphones which were rolled out in 2010 (Jacobs, Citation2013; Gauteng Department of Education, Citation2014). With the total costs of R15 million for project implementation and operation annually, the Tablets and phones are provided with R400 airtime as a top-up prepaid system (Jacobs, Citation2013; Gauteng Department of Education, Citation2014). All designated officials have personal e-mail addresses which enable them to access data to facilitate effective communication while receiving training support by technical staff members from the Department of Education on using the devices (Jacobs, Citation2013).

The ‘Big Switch On Pilot Project’ was launched in 14 January 2015 by the Gauteng Province MEC of Education, Mr Panyaza Lesufi in collaboration with the then Deputy President of the Republic of South Africa, Mr Cyril Ramaphosa, and other government officials in seven schools within the province (Maune, Citation2015; Phakathi, Citation2015; Ramoroka & Tsheola, Citation2015; South Africa.Info, Citation2015a). The Big Switch On Pilot Project is ‘a paperless education system which will give learners access to learning materials, workbooks and other subject matter through the use of ICT’ (South Africa.Info, Citation2015a:n.p cited in Ramoroka & Tsheola, Citation2015). The aim of the project was to promote ‘paperless classrooms’, reliant on digital technologies for collaborative teaching and learning in all high schools in the province by 2019 (Maune, Citation2015; Ramoroka & Tsheola, Citation2015). The Big Switch on Project is one of the steps in realising Gauteng Province's vision of ‘building a world-class education system by modernising public education and improving the standard of performance across the entire system’ (South Africa.Info, Citation2015a:n.p.). Accordingly, the schools received ‘state-of-the-art internet connection’, interactive LED whiteboards whereas each learner was provided with a tablet with the hope of transforming ordinary schools into technological ‘classrooms of the future’ (South Africa.Info, Citation2015a). Learners from some of the seven schools confirmed that the tablets will make their knowledge acquisition more exciting and that there would not be any reason to fail science or maths ever (South Africa.Info, Citation2015a).

From the pilot phase that was implemented in the seven schools, a mere six months later, an additional 375 high schools mainly in township and rural areas were embraced into the Big Switch On Project (Areff, Citation2015; Bothma, Citation2015; Monama, Citation2015; Nkosi, Citation2015). On 21 July 2015 the MEC of Education in Gauteng Province, Mr Panyaza Lesufi, officially implemented the Big Switch on Project at the 375 high schools which offers Grade 12 wherein all learners and teachers were given Tablets and laptops, respectively with unlimited data bundles from 5 am to 9 pm daily for educational purposes (Areff, Citation2015; Bothma, Citation2015; Monama, Citation2015; Nkosi, Citation2015; Mzekandaba, Citation2016). Even though teachers and Grade 12 learners have unlimited access to the Internet for free, which is connected to a server through ‘broadband’, ‘Wi-Fi’ and ‘4G’, all social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp and other irrelevant sites are banned from the Tablets and the laptops (Nkosi, Citation2015). According to Mr Lesufi, ‘Almost 98% of the teachers in the schools sacrificed their school holidays to be trained’ to be able to use technology in knowledge transfer and acquisition (Areff, Citation2015; Bothma, Citation2015; Monama, Citation2015; Nkosi, Citation2015; Mzekandaba, Citation2016). He further asserted that teachers would, overnight, never give learners an exercise through an exercise book. He argued that ‘Chalkboards were becoming a thing of the past in Gauteng. (and that) chalkboard and duster … (would be relegated) to a museum’ (Areff, Citation2015:n.p.; Nkosi, Citation2015:n.p.). More than 4000 Grade 12 classrooms were renovated by changing ceilings, fitting specialised lights and installing blinds to improve the environment for the 1800 interactive smartboards while 17 000 tablets, fitted with security tracking devices, were distributed (Bothma, Citation2015; Mzekandaba, Citation2016). In 2015, only Grade 12 learners are taught using ICT in the 375 schools (Areff, Citation2015; Bothma, Citation2015; Monama, Citation2015; Mzekandaba, Citation2016).

5.2. Smart schools in Western Cape Province

The Western Cape Province has also made massive investments for the ‘Smart Schools Project’ launched in July 2015 for improving the quality and standard of teaching and learning (Mawson, Citation2015; Phakathi, Citation2015; Western Cape Department of Education, Citation2015; South Africa.Info, Citation2015b; Mzekandaba, Citation2016). According to the former Premier of the province, Helen Zille’s, Citation2015 State of the Province Address, R1.2 billion was invested for the following five years specifically for the establishment of ICT infrastructure and e-learning in schools. Hellen Zille asserted that ‘the rate of increase in the Western Cape's pupil numbers’ meant that the province would ‘never … afford the number of teachers … need’ instead, ‘e-learning will have to play an increasingly important complementary role to supplement the teachers in … schools’ (Mzekandaba, Citation2016:n.p.). Accordingly, 1250 schools would be beneficiaries of the ‘Smart Classroom Project’ over five years, starting from 2015 (Fredericks, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Mawson, Citation2015; Zille, Citation2015; Mzekandaba, Citation2016). The Smart Classroom Project aimed at providing all classrooms in the Western Cape Province with Wi-Fi connectivity to broadband, digital projector, whiteboard and teacher computing device, which serves as minimum technological resources for the implementation of e-learning (Fredericks, Citation2015a; Western Cape Department of Education, Citation2015). The classrooms are further provided with mobile trolleys, overhead projectors and laptops, among other gadgets to assist in teaching and learning, while 126 computer laboratories mostly in poor schools were completed by the end of April 2015 (Fredericks, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Mawson, Citation2015; Phakathi, Citation2015; Western Cape Department of Education, Citation2015; Zille, Citation2015). The implementation of e-learning in the province is expected to assist in tackling some of the problems faced, including increasing access to quality education in disadvantaged communities, providing support for struggling learners, contributing towards teachers’ training and professional development, and improving management and administration at schools (Fredericks, Citation2015b; Phakathi, Citation2015; Western Cape Department of Education, Citation2015). It seeks to provide learners with the skills for participation in the ‘increasingly technology-based economy in the future’ (Western Cape Department of Education, Citation2015:n.p.).

The Western Cape Government’s aim was to connect the majority of schools to the WAN by the end of 2016. A total number of 1250 schools should have been connected to ‘high-speed broadband’ by July 2016 together with 366 schools which were connected by June 2015 (Mawson, Citation2015; Phakathi, Citation2015; Western Cape Department of Education, Citation2015; Mzekandaba, Citation2016). As of mid-2016, a total number of 692 schools have been connected, with 92 libraries whereas 169 corporate sites were developed. Additionally, the Western Cape government confirmed that it managed to deliver more than 3300 smart classrooms during the 2014/15 financial year (Mzekandaba, Citation2016). The Western Cape Department of Education introduced the ‘Smart School Project’, which includes refreshing of the existing Khanya Project laboratories and the provision of ‘Smart Classrooms’, in order to fully utilise their Internet networks which were created through the ‘WAN’ and the ‘LAN’ specifically for teaching and learning purposes (Mawson, Citation2015; Phakathi, Citation2015; Western Cape Department of Education, Citation2015).

6. Prospects of South Africa’s successful implementation of digital technology for education

The NDP 2030 confirms that the implementation of educational technology is a good, provided that it is supported by ‘effective governance’ and funding mechanisms to promote ‘coordination and collaboration’ among various stakeholders (National Planning Commission, Citation2012), which is the missing link in the two provinces digital rush in South Africa. In practice, there is a challenge between what policy legislation and plans prescribe in terms of the provision of educational ICT and what is actually happening in the school classrooms. South Africa’s policy legislation and plans recommend provision of ICT infrastructure in all schools without a clear prescription of the strategy and processes to be followed. Hence, replacement of conventional didactics with e-learning predominates blending at provincial scale. However, the challenge for South Africa remains that the same ICT transformation in education has been unsustainable and inefficient even for some of the most developed countries with very high human development index. Therefore, South Africa’s expectation of sustainability and effectiveness of the infrastructure provision for participation in the global knowledge economy and national development cannot be guaranteed. A quantitative comparative analysis through Principal Components (PC) based on correlations reveals the challenges that South Africa is facing.

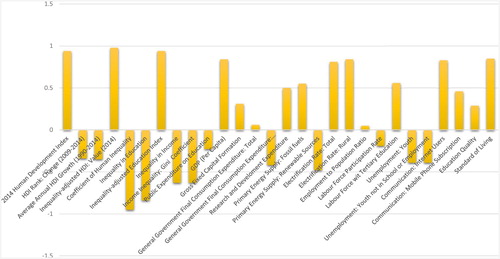

Correlation matrix is a ‘parametric statistic that provides a more accurate measure of coefficient of determination most widely used in spatially-oriented research’ (Tsheola, Citation2012:1059). Furthermore, it was used as a descriptive measure of strength and direction of correlations and as measures of the linear relationships between variables based on the basis of the assumption that the form of the relationship is linear (Edbon, 1985:97 cited in Tsheola, Citation2012). Therefore, the correlation matrix describes the relationship between pairs of variables. Given that the raw data consisted of 15 observations by 28 variables, a 28 by 28 variables correlation matrix was constructed (). That is, each of the 28 variables is correlated with the twenty-seven as well as itself. Hence, the matrix consists of a diagonal line ranging from top left to bottom right of perfect direct correlations of 1.00. That diagonal set of correlations describes relationships of each variable with itself. To this extent, each side of the diagonal line is a reflection of the other. However, in this study, the relationship between Y and X is similar to that between X and Y, without insinuating a cause–effect relationship. Therefore, the analysis of the correlation matrix will be based on only one side of the diagonal line.

Table 1. Correlation matrix of 15 selected countries by 28 variables.

6.1. Principal Components 1 and 2

Twelve (12) of the 28 variables have strong positive loadings on PC 1; and, stated in the descending order, they are Inequality-adjusted HDI (0.98), Inequality-adjusted Education Index (0.94), HDI (0.94), Standard of Living (0.85), per capita GDP (0.84), Rural Electrification Rate (0.84), Internet Users Communication (0.83), Total Electrification Rate (0.81), Mobile Phone Subscription Communication (0.46), Research & Development Expenditure (0.50), Fossil Fuels Primary Energy Supply (0.55), Labour Force with Tertiary Education (0.56). But the strongest positive loadings relate to only three variables, which are Inequality-adjusted HDI (0.98), Inequality-adjusted Education Index (0.94) and HDI (0.94) (). The second category of the strongest positive loadings is in the range 0.80-0.85; and, they include five variables as follows: Standard of Living (0.85), per capita GDP (0.84), Rural Electrification Rate (0.84), Internet Users Communication (0.83) and Total Electrification Rate (0.81). The next strongest positive loadings involve four variables in the range 0.46-0.56, which are: Mobile Phone Subscription Communication (0.46), Research & Development Expenditure (0.50), Fossil Fuels Primary Energy Supply (0.55) and Labour Force with Tertiary Education (0.56). However, Mobile Phone Subscription Communication also loads positively and relatively strongly on PC 2 (0.54) and PC 5 (0.50) (). Collectively, these positive loadings on PC 1, especially the strongest ones, imply that this PC describes multifaceted development, which transcends the usual modernisation philosophy to encapsulate societal equality and equitable access to national resources. Furthermore, there is evidence of social development as denoted in the strong positive loadings of variables related to education, standard of living and human development.

This observation is supported by the pattern of four negative loadings that are strong on PC 1, which include: Human Inequality Coefficient (−0.95), Inequality in Education (−0.84), Income Inequality Gini-coefficient (−0.68) and Inequality in Income (−0.63). That is, PC 1 is strongly and directly associated with progressive qualities of equitable multifaceted societal development as well as inversely and strongly correlated with variables that denote antithesis of the three values of development, which are standard of living, high self-esteem and freedom of choice, especially due to the significance of labour force with tertiary education, as well as relatively low levels of societal inequality in education, income and access to basic resources. The strong positive loading of Internet use for communication (0.83), together with the virtually universal access to electricity, inclusive of rurality, should suggest that connectivity through modern infrastructure and technologies are at relatively advanced state. Therefore, it would not be farfetched to denote PC 1 as a representation of modern development with first world infrastructure, education, culture, skills and expertise, economic performance and governance that serve to regulate societal ills and inequality downward by providing equitable access and opportunity to societal progress. These development qualities and eventualities are evidence of advanced planning and management.

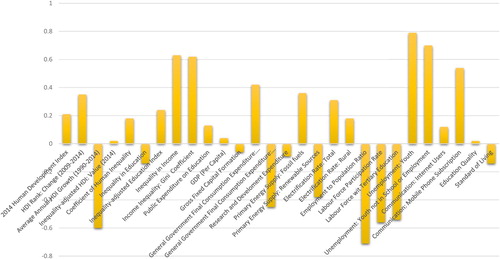

On its part, PC 2 is characterised by two relatively strongest positive loadings of Youth Unemployment (0.79) and Unemployment among Youth who are not in School (0.70). Additionally, the PC is associated with two strong positive loadings of Income Inequality (0.63) and Income Inequality Gini-coefficient (0.62) (). Together, these strong and relatively strongest positive loadings on PC 2 signal antithesis to shared societal modernisation and development. A society in conditions as described in this PC should be far less prepared for blended pedagogies; and, unrelenting push for e-infrastructure, e-governance, e-skills and e-culture will be mere attempt at imposition of e-learning and therefore a replacement behaviour rather than integration of conventional didactic with digital technologies. Hence, the use of mobile phones for communication loads relatively strongly and positively (0.54) on PC 2, simultaneously with relatively strong negative loadings of Employment as Ratio of Population (−0.71), HDI Annual Growth (−0.60), Labour Force Participation Rate (−0.56) and Labour Force with Tertiary Education (−0.54).

This combination of loadings indicates that PC 2 involves the antitheses of development, which include societal inequality, slow annual growth in HDI (if not stagnation), negligible access to resources as attested to by total and rural electrification (0.31 and 0.18, respectively) as well as supplies of fossil fuels and renewable energy (0.36 and −0.38, respectively). This PC can be justifiably denoted as Frustrated Development, where the struggle for modernisation has exacerbated societal inequities. Amidst these indications of frustrated development, Annual Average Growth in Government Consumption Expenditure is negatively loaded (−0.45) on PC 2, implying that the state is struggling for resources mobilisation and wealth generation because the reasonable positive loading of Total Government Consumption Expenditure (0.42) suggests that there is political and administrative will to promote shared societal progress. Therefore, a country that scores positively and highly on PC 2 would imply the absence of an enabling environment for the implementation and operationalisation of blended pedagogies. That is, the status of governance, infrastructure, skills and culture would remain less optimal for the adoption of blended pedagogies.

6.2. Country scores on Principal Components 1 and 2

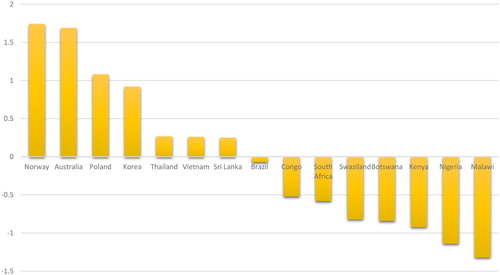

South Africa's component score on PC 1 is −0.58 (), which would in terms of the analysis mean that this country lacks the character of modernised planning, governance, infrastructure, skills and culture necessary for engendering blended pedagogies. In this way, South Africa cannot be expected to successfully plan and execute blended pedagogies because of the inherent deficiencies in governance, infrastructure, skills and culture. It is for this reason that countries such as Norway, Australia, Poland, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka that have variably trotted the blended pedagogies route are on the opposite side of South Africa in terms of their component scores on PC 1. Besides, some of these countries have not been fully successful in blended pedagogies notwithstanding their apparently enabling environment. The countries that have relatively successfully trotted with blended pedagogies with some degree of enabling environment in this case can be classified into three categories.

The relatively highly successful category would include Norway and Australia, followed by the group of Poland and Korea, and the class of Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka. However, even countries such as Norway and Australia that have successfully established credible enabling environment for blended pedagogies have continued to experience serious problems of scepticism and user apathy and/or resistance (Peeraer & Van Petegem, Citation2015; Park et al., Citation2016; Pruet et al., Citation2016). Also, Poland and Korea, which are relatively advanced in terms of modernisation, planning processes, governance, infrastructure, skills and appropriateness of the e-learning culture in comparison with South Africa, have continued to struggle to attain complete adoption and buy-in with regard to integration of digital technologies with conventional didacticism. It has to be mentioned that South Africa is in terms of modernised planning, governance, infrastructure, skills and culture some distance below Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka. Yet, South Africa is in the same Medium HDI category as Vietnam, explaining the significance of variable maturity of the planning and governance processes (see ).

Table 2. HDI category and range of sampled countries.

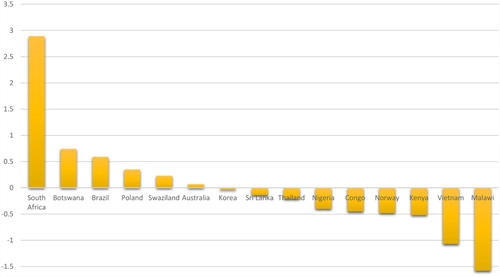

Given that South Africa is in the Medium HDI, questions of appropriateness of its planning, governance, infrastructure, skills and culture are indictment for trotting with e-learning in an environment of deep societal inequities and regional inequalities. The negative component score on PC 1 means that South Africa’s education, standard of living and human development are not supportive of the necessary situational prerequisites for the implementation of blended pedagogies. South Africa's component score on PC 2 is extraordinarily higher than all of the 14 countries (see ). This country's score is 2.89, which 2.15 higher than the nearest score. Countries that have relatively successfully trotted with blended pedagogies such as Vietnam, which is in the same Medium HDI Category as South Africa, have far lesser positive and mostly significantly larger negative scores on PC 2. Indeed, South Africa is characterised by high levels of Youth Unemployment and Unemployment of Youth not in School that is succinctly captured by PC 2. Youth are the drivers of the adoption of digital technologies, especially the social media (Domingo & Garganté, Citation2016; Hung, Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2016; Pruet et al., Citation2016; Salminen et al., Citation2016). The concept of ‘Net Natives’ attests to the leading role of youth in digital technologies; and, youth are supposed to be creating pressure in schools and universities for the adoption and implementation of e-learning. Given that Youth Unemployment is high, especially with youth that are not in school, it means that South Africa lacks the quality that is required for the adoption and implementation of digital technologies. Thus, one major challenge that South Africa is facing is societal refreshment for the future. To this extent, it would be difficult to envision how South Africa could probably implement blended pedagogies in a situation where youth are out of school and unemployed.

Other than unemployment of youth, South Africa's significantly large positive score on PC 2 shows that this country is also deeply unequal. Societal inequality in income and inequities in human development described in PC 2 are deep. Besides, South Africa's move in Gauteng and Western Cape provinces would instead serve to accentuate the societal inequalities and inequities. Clearly, the use of mobile phones in South Africa is itself ubiquitous whilst the population is generally experiencing high levels of unemployment with lack of growth in HDI, declining rates of Labour Participation in the economy, large proportions of Labour Force without Tertiary Education, as well as continuing limitations in access to electrification and heavy reliance on fossil fuels, points to poverty of planning and governance. Overall, South Africa's negative score on PC 1 and positive on PC 2 shows that there has been a serious failure in planning and governance because a country cannot hope to adopt and implement e-learning without prior preparations based on material conditions of the nation. Indeed, South Africa is symptomatic of frustrated development wherein societal inequalities are exacerbated by failed modernisation projects as the state struggled for resources mobilisation with high levels of Government Consumption Expenditure. This scenario points to a bloated bureaucracy, devoid of modernised planning nor governance, which would constitute environmental limitations as demonstrated in the literature review (see for example, Stern et al., Citation2009; Carlson et al., Citation2013; Lysko et al., Citation2013; Ramoroka, Citation2014; Masonta et al., Citation2015).

7. Conclusion

This paper revealed the principles and processes of various teaching and learning approaches which include conventional didactics, e-learning and blended pedagogies. Drawing from the discussed experiences from Gauteng and the Western Cape Provinces, in the context of the comparative PCA interpretation provided in the paper, the massive investments made for e-learning environments in a democratic South Africa are questionable. For both provinces, the appropriateness of the adopted planning approaches, governance models, infrastructure, skills and culture need to be evaluated especially for online teaching and learning environment. The two provinces seem to be replacing conventional didactics with e-learning instead of the implementation of blended learning because South Africa itself does not meet the preconditions as determined through comparative analysis with 14 other countries in different categories of the HDI. Like many other countries, South Africa’s educational ICT infrastructure may present an appearance of being appropriate but, its planning approaches, governance models, teachers’ and learners’ skills and e-culture should be questioned for successful, sustainable and effective implementation of a totally online pedagogic environment. There is a realistic potential for the societal inequalities to be exacerbated in a democratic South Africa through ICT interventions that were designed to undermine the divides in the first place. The paper recommends that the nation should first seek to establish the minimum standards as set in the preconditions, rather than allow for ad hoc expressions such as those of Gauteng and Western Cape provinces.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akyuz, D, 2018. Measuring technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) through performance assessment. Computers & Education 125, 212–25.

- Annie, P, Ndhlovu, D & Kasonde-Ng’andu, S, 2015. Establishing traditional teaching methods used and how they affected classroom participation and academic performance of learners with visual impairment in Zambia. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development 2(3), 397–412.

- Areff, A, 2015. Unlimited data for Gauteng township schools as they go digital. News24. http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/Unlimited-data-for-Gauteng-township-schools-as-they-go-digital-20150720. Accessed 23 July 2015.

- Bialobrzeska, M & Cohen, S, 2005. Managing ICTs in South African schools: A guide for school principals. South African Institute for Distance Education (SAIDE), Johannesburg.

- Bothma, B, 2015. Gauteng Education Department to expand ‘paperless classroom’ technology. eNCA, https://www.enca.com/technology/gauteng-education-department-extend-paperless-classroom-technology. Accessed 23 July 2015.

- Carlson, J, Ntlatlapa, N, King, J, Mgwili-Sibanda, F, Hart, A & Geerdts, C, 2013. Studies on the use of television white spaces in South Africa: Recommendations and learnings from the Cape Town television white spaces trial. https://www.tenet.ac.za/tvws/recommendation-and-learnings-from-the-cape-town-tv-white-spaces-trial. Accessed 12 December 2015.

- Department of Basic Education, 2011. Curriculum and assessment policy statement: Further education and training phase grades 10-12. Department of Basic Education, Johannesburg.

- Department of Education, 2002. Revised national curriculum statement for grades R-9. Department of Education, Pretoria.

- Department of Education, 2004. White paper on e-education. Department of Education, Pretoria.

- Domingo, MG & Garganté, AB, 2016. Exploring the use of educational technology in primary education: Teachers’ perception of mobile technology learning impacts and applications’ use in the classroom. Computers in Human Behavior 56, 21–8.

- Farrukh, S & Singh, SP, 2014. Teachers’ attitude towards use of ICT in technical and non-technical institutes. Journal of Educational and Social Research 4(7), 153–60.

- Fredericks, I, 2015a. Cape classrooms set to go Hi-tech. IOL News. http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/western-cape/cape-classrooms-set-to-go-hi-tech-1886429. Accessed 4 August 2015.

- Fredericks, I, 2015b. Wi-fi to be rolled out in W Cape schools. IOL News. http://www.iol.co.za/scitech/technology/internet/wi-fi-to-be-rolled-out-in-w-cape-schools-1824527. Accessed 9 March 2016.

- Gauteng Department of Education, 2014. Annual report 2013/2014. Gauteng Department of Education, Pretoria.

- Gu, X, Shao, Y, Guo, X & Lim, CP, 2015. Designing a role structure to engage students in computer-supported collaborative learning. Internet and Higher Education 24, 13–20.

- Han, X, Wang, Y & Jiang, L, 2019. Towards a framework for an institution-wide quantitative assessment of teachers’ online participation in blended learning implementation. The Internet and Higher Education 42, 1–12.

- Hart, SA & Laher, S, 2015. Perceived usefulness and culture as predictors of teachers attitudes towards educational technology in South Africa. South African Journal of Education 35(4), 1–13.

- Hung, M-L, 2016. Teacher readiness for online learning: Scale development and teacher perceptions. Computers & Education 94, 120–33.

- Jacobs, M, 2013. Tablets, smartphones for Gauteng principals. ITWeb Training and Learning. http://www.itweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=64613. Accessed 9 March 2015.

- Lysko, A, Masonta, M & Mfupe, L, 2013. Field measurements done on operational TVWS trial network in Tygerberg. Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria.

- Masonta, MT, Ramoroka, TM & Lysko, AA, 2015. Using TV White Spaces and e-learning in South African rural schools. In Cunningham, P & Cunningham, M (Eds.), IST-Africa 2015 conference proceedings. IIMC International Information Management Corporation, Ireland, pp. 1–12.

- Maune, B, 2015. Education Department to add security features to tablets and return them to school. Sunday Times. http://www.timeslive.co.za/scitech/2015/05/15/education-department-to-add-security-features-to-tablets-and-return-them-to-schools. Accessed 5 May 2015.

- Mawson, N, 2015. W Cape pulls ahead in broadband race. ITWeb Wireless. http://www.itweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=141361. Accessed 9 March 2016.

- Mayisela, T, 2013. The potential use of mobile technology: Enhancing accessibility and communication in a blended learning course. South African Journal of Education 33(1), 1–18.

- Monama, T, 2015. Soweto School Set to Go Digital. IOL News. http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/gauteng/soweto-school-set-to-go-digital-1886189. Accessed: 23 July 2015.

- Mzekandaba, S, 2016. Paperless Classroom Hotspot for Thieves. ITWeb Security. http://www.itweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=145049. Accessed 9 March 2016.

- National Planning Commission, 2012. National development plan 2030: Our future-make it work. Government Printers, Pretoria.

- Nkosi, B, 2015. ‘Chalkboards are now a thing of the past’ – Lesufi. Mail & Guardian. http://mg.co.za/article/2015-07-21-chalkboards-will-be-a-thing-of-the-past-lesufi-1. Accessed 21 July 2015.

- Nyagowa, HO, Ocholla, DN & Mutula, SM, 2013. The influence of infrastructure, training, content and communication on the success of NEPAD’S pilot e-schools in Kenya. Information Development 30(3), 235–46.

- Park, Y, Yu, JH & Jo, I-H, 2016. Clustering blended learning courses by online behaviour data: A case study in a Korean higher education institute. Internet and Higher Education 29, 1–11.

- Peeraer, J & Van Petegem, P, 2015. Integration or transformation? Looking in the future of Information and Communication Technology in education in Vietnam. Evaluation and Program Planning 48, 47–56.

- Phakathi, B, 2015. Western Cape rolls out e-learning to improve schooling. BDlive, http://www.bdlive.co.za/national/education/2015/02/23/western-cape-rolls-out-e-learning-to-improve-schooling. Accessed 5 March 2015.

- Pruet, P, Ang, CS & Farzin, D, 2016. Understanding tablet computer usage among primary school students in underdeveloped areas: Students’ technology experience, learning styles and attitudes. Computers in Human Behavior 55, 1131–44.

- Ramoroka, T, 2014. Wireless internet connection for teaching and learning in rural schools of South Africa: The University of Limpopo TV white space trial project. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5(15), 355–9.

- Ramoroka, T & Tsheola, J, 2015. E-didactics and e-learning for modern development in the Western Cape Province, South Africa: Pros and cons. Proceedings of the 3rd Biennial Conference on Business Innovation and Growth, pp. 170–82.

- Ramoroka, T & Tsheola, J, 2016. Blended pedagogies for modern development in South Africa: Challenges and prospects for success. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology 13(1), 56–67.

- Ramoroka, TM, Tsheola, JP & Sebola, MP, 2016a. Governance of blended pedagogies in the 21st century for participation in the knowledge economy. In MP Sebola & JP Tsheola (Eds.), Governance in the 21st century organisation. International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives (IPADA), Polokwane. pp. 454–78.

- Ramoroka, TM, Tsheola, JP & Sebola, MP, 2016b. Planning and governance of blended pedagogies for national development in South Africa: Is the puzzle complete without the local government? In MP Sebola & JP Tsheola (Eds.), 20 years of South Africa’s post-apartheid local government administration. South African Association of Public Administration and Management (SAAPAM), Pretoria, pp. 334–41.

- Ramoroka, T, Tsheola, J & Sebola, MP, 2017a. E-culture as a panacea for successful implementation of blended pedagogies in South Africa. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology 14(2), 31–40.

- Ramoroka, T, Tsheola, J & Sebola, MP, 2017b. Planning for blended pedagogies: appropriateness for modern transformation in the 21st century. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology 14(1), 16–32.

- Ramoroka, T, Tsheola, J & Sebola, MP, 2017c. South Africa’s pedagogical transformation for participation in the global knowledge economy: Is it a panacea for modern development? African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 9(3), 315–22.

- Salminen, L, Gustafsson, M, Vilén, L, Fuster, P, Istomina, N & Papastavrou, E, 2016. Nurse teacher candidates learned to use social media during the international teacher training course. Nurse Education Today 36, 354–9.

- South Africa.Info, 2015a. South Africa turns on digital classroom. South Africa.Info. http://www.southafrica.info/about/education/paperless-education-14115.htm. Accessed 5 March 2015.

- South Africa.Info, 2015b. South Africa’s Western Cape invests in E-learning. South Africa.Info. http://www.southafrica.info/about/education/elearning-230215.htm. Accessed 5 March 2015.

- Stern, MJ, Adams, AE & Elsasser, S, 2009. Digital inequality and place: The effects of technological diffusion on Internet proficiency and usage across rural, suburban, and urban counties. Sociological Inquiry 79(4), 391–417.

- Tsheola, J, 2012. Trade regionalism, decolonization-bordering and the new partnership for Africa’s development. China-USA Business Review 11(8), 1051–68.

- Tsheola, J, Ramoroka, T & Sebola, M, 2017. South Africa’s “structural power”: “Competition” states in the globality of private economies of selected countries. Journal of Global Business and Technology 13(2), 82–95.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), 2015. Human development report 2015 – Work for human development. United Nations Development Programme, New York.

- Valtonen, T, Kukkonen, J, Kontkanen, S, Sormunen, K, Dillon, P & Sointu, E, 2015. The impact of authentic learning experiences with ICT on pre-service teachers’ intentions to use ICT for teaching and learning. Computers and Education 81, 49–58.

- Webster, TE & Son, JB, 2015. Doing what works: A grounded theory case study of technology use by teachers of English at a Korean university. Computers and Education 80, 84–94.

- Western Cape Department of Education, 2015. WCED announces details on e-learning “smart schools” project. Western Cape Department of Education, Cape Town.

- Wolff, M, Wagner, MJ, Poznanski, S, Schiller, J & Santen, S, 2015. Not another boring lecture: Engaging learners with active learning techniques. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 48, 85–93.

- Zille, H, 2015. State of the province address. Western Cape Office of the Premier, Cape Town.