ABSTRACT

Gender-based structural inequalities in Southern African cities continue to drive poverty and food insecurity in spite of decades of development efforts to raise the social, economic, and political status of women relative to men. A 2014 survey of household food security in Maputo found that female headship is closely associated with food insecurity. This article assesses the role of employment and education in explaining this phenomenon in the city of Maputo. Using household survey data, this investigation defines the extent to which the relationship between the sex of the household head and food insecurity appears to be conditionally dependent upon employment and education. The findings provide further impetus to urban policy makers to operationalise gender equality goals.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of cities across Southern Africa has led to increasing levels of urban poverty related to inadequate housing, water and sanitation systems, employment opportunities, and social protection mechanisms.Footnote1 Urban food security is increasingly gaining attention as a cross-cutting issue with causal factors operating across scales and a range of effects on development goals for improved public health, education, environmental sustainability, and social inclusivity (Battersby, Citation2012; Frayne et al., Citation2018). Insufficient attention has been paid to the nuanced ways in which power imbalances based on gender difference shape food security outcomes in Southern African cities (Riley & Hovorka, Citation2015). This policy blind spot exists in spite of the close association between gender roles and food-related tasks at the household scale (Quisumbing et al., Citation1995), and the widely recognised link between gender and urban poverty (Chant, Citation2013; Moser, Citation2017). In many cases, these relationships are so taken for granted that they rarely attract attention from data analysts and the study of ‘gender and urban food security’ tends to be addressed with qualitative and ethnographic data that is difficult to scale up to inform policy debates (Dodson et al., Citation2012).

This article addresses the gap in city-scale household food security analysis using data on 2,071 households gathered by the Hungry Cities Partnership in Maputo, Mozambique. Section two provides information about the research context of Maputo. Section three outlines the methods employed in data collection and analysis. Section four presents the findings from this analysis. Finally, section five provides a discussion of the implications of these findings for policy development in Maputo.

2. Research context

Gender politics in Mozambique are unique in the region because of the influence of Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Mozambique Front Liberation) or FRELIMO policies directed at realising an ideal of gender equality through its revolutionary period in the 1970s and 80s. Urdang (Citation1983: 9) quoted a woman saying at a party rally in the late 1970s, ‘FRELIMO says that all of us, women and men, can develop our minds, all of us can work. FRELIMO knows that women can think very well, that women are as capable of making decisions.’ Raimundo (Citation2010) explains that the the enactment of the women’s emancipation policy following the liberation war (1964-1975) allowed women to break from cultural proscriptions that inhibited their role as decision-makers (Citation2010: 32). The emancipation of women was a key pillar in the distinction between colonial and postcolonial societies, fitting well with the three ideological goals of modernism, nationalism and socialism (Pitcher, Citation2002). These goals resonated most profoundly in urban Mozambique which housed one of Africa’s most industrialised economies at the time of independence.

Despite the implementation of progressive policies and the availability of opportunities for urban employment, the ideal of gender equality has been divorced from the reality for most women. While the reality falls short of the ideal of gender equality in many ways, there is evidence of female-headed households escaping poverty at a more rapid rate than male headed households (Tvedten et al., Citation2013). This is partly due to the growing proportion of female headship across all economic classes in Maputo and a growing diversity of female headed households. The rising number of female headed households can also be read in many cases as an expression of women’s agency in configuring their households, as Raimundo et al. (Citation2014: 6) note: ‘Women are taking increasing control over their own lives by forming female-headed households and establishing close female-focused social networks.’

The experiences of food insecurity at the household scale are instrumental in measuring the extent to which economic marginalisation is manifested in the multiple consequences of chronic food insecurity. In a survey of over 2,000 households in Maputo, McCordic (Citation2016) found that only 28.6% of surveyed households in Maputo were food secure, 11% were mildly food insecure, 22% were moderately food insecure, and 38.3% were severely food insecure. Previous research has also indicated that the sex of household heads in Maputo predicts household experiences of poverty and food insecurity. Using a 2008 household survey of poor areas in eleven Southern African cities, Dodson et al. (Citation2012) demonstrated that female-centred households were generally more food insecure. That said, among the low-income households in that survey, female-centred households appeared to have better food security outcomes than nuclear households. This observation fits with a broadly accepted idea that investments directed toward women will have a greater net benefit to households, especially vulnerable household members, than investments directed to men (Haddad et al., Citation1997; Ruel et al., Citation1998). Evidence in the context of Maputo was provided by Sahn & Alderman (Citation1997) who suggested that the education of mothers in Maputo significantly predicted infant stunting while the level of overall household income indicated a statistically significant relationship with the nutritional status of older children in the household.

Garrett & Ruel (Citation1999) suggested that, based on a national demographic and expenditure survey of Mozambique, height-for age stunting of children was significantly associated with both household income and the education-level of household heads. The authors suggested that these differences may also explain urban and rural differences in nutrition (with females having a much greater chance of being educated in urban areas). While the authors included household head gender in their analysis, this variable was not a significant predictor of stunting when other demographic variables (like education) were controlled for. McCordic (Citation2016, Citation2017) also found, using a household survey of Maputo, that the relationship between the gender of the household head (as well as the marital status of the household head) and household food insecurity was statistically insignificant when the influences of household infrastructure access was controlled for. The Hungry Cities Partnership data provides an opportunity to revive the research discussion on the instrumental role of investing in women’s education and employment opportunities as a pre-condition of progress on other goals such as urban food security.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Research objectives

This investigation is guided by the following research objectives:

Research Objective One: Determine whether there is a predictive relationship between the sex, education and employment status of the household head and the food security status of the household in a household survey of Maputo.

Research Objective Two: Identify whether the relationship between the sex of the household head and household food security status is conditionally dependent upon the education and employment of the household head among the surveyed households in Maputo.

3.2. Sample

The household survey sample used in this investigation was drawn from a city-wide survey of 2,071 households in Maputo, Mozambique in 2014 by the Hungry Cities Partnership. The survey instrument administered to these households included scales on food insecurity, poverty, food sources, food purchasing patterns, and demographic data. The sampling strategy used in this fieldwork relied on a two-stage design. In the first stage, 19 wards were randomly selected within the city. Within each of these wards, an enumerator team from the University of Eduardo Mondlane used systematic sampling to select households for the survey. The total household sample size was also distributed across the selected wards using approximate proportionate allocation (the most recently available census data at the time was from 2007).

3.3. Variables

This investigation included the following variables: the Household Food Insecurity Access Prevalence (HFIAP) scale, the sex of the household head, the employment status of the household head and the education level of the household head (). The Household Food Insecurity Access Prevalence (HFIAP) tool measures food security based on the frequency and severity of food access challenges faced by households over the previous four weeks (Coates et al., Citation2007). These food access challenges are determined by nine Likert scale questions which assess multiple dimensions of food access challenges at varying degrees of severity. Using a scoring algorithm, the answers to these questions were then used to categorise the sampled households according to their ranked food security status. For the purposes of this investigation, this ranked score was then dichotomised as a binary variable indicating whether a household was judged to be food secure (a score of 1 on the HFIAP) or food insecure (a score of 2–4 on the HFIAP) by this scale (this variable binning, allowed for more direct comparisons of adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios).

Table 1. Investigation Variables.

This investigation also includes three demographic variables: the sex of the household head, the education level of the household head, and the employment status of the household head. The education level of the household head demonstrates whether the household head has had any formal education. The employment status of the household head demonstrates whether the household head is employed (formally or informally, full-time or part-time) or unemployed (including pensioners, housewives, and those individuals not medically able to work).

3.4. Analysis

All analyses in this investigation were carried out using IBM SPSS 27 and SPSS Modeler 18. In order to achieve the first research objective, this investigation relied on odds ratios and chi-square tests of independence. Odds ratios allow for an assessment of the distribution of households in cross-tabulations of the variables included in this investigation. In this analysis, an odds ratio value greater than one indicates an increase in the odds of food insecurity given a change in the demographic variables in this investigation (e.g. a change from male to female in the sex of the household head). The p-values for these odds ratios were calculated using Pearson’s chi-square tests of independence. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (calculated using simple random sampling to select 1,000 bootstrap samples) have been included for these odds ratio calculations.

The second research objective was achieved by this investigation using adjusted odds ratios, Bayesian Network analysis, and Chi-square Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID) decision tree analysis. The adjusted odds ratio calculations were calculated using binary logistic regression analysis. These binary logistic regression models included all the variables in this investigation. In other words, this modelling calculated the odds ratio value describing the sex of the household head with the HFIAP variable while controlling for the education and employment status of the household head (based on Maximum Likelihood Estimation). Bootstrapped p-values (calculated using simple random sampling to select 1,000 bootstrap samples) have been included for the logistic regression analysis. This investigation also included a Bayesian Network which, using the Markov Blanket for the HFIAP variable, determined any conditionally dependent relationships between the variables in the investigation via a constraint-based learning algorithm (as determined by a Pearson’s Chi-Square test of independence at an alpha of 0.01 using a maximal conditioning set size of 5).

The Bayesian Network determined whether any statistically significant relationships between the variables in this investigation (based on chi-square analysis) remained significant given sub-sets of the other variables included in the investigation. Using this method, the statistically significant relationships in the Bayesian Network are indicated by an edge between the variables. The direction of these edges does not imply causality and is established via arc orientation rules in the Markov Blanket Arc learning algorithm in SPSS Modeler 18. Finally, this research objective was achieved and further explained using a CHAID decision tree to determine the categorisation of female and male-headed households using the employment status and education level of the household head as categorising variables. The CHAID decision tree was built using an exhaustive CHAID learning algorithm which used Pearson’s chi-square tests of independence to determine what variables to split upon and used stopping rules to avoid over-fitting (a minimum of 2% of the sample was allowed for any parent branches and a minimum of 1% of the sample was allowed for any child branches). The exhaustive CHAID learning algorithm operates by identifying the independent variable with the highest chi-square value against the dependent variable as a splitting variable. The algorithm then repeated the process within each category in this variable (and repeats the process again within each sub-set of those variables) until the stopping rules are triggered.

4. Results

4.1. Research Objective One results

The frequency distribution of the independent variables in this investigation against the HFIAP variable indicated some interesting findings (). Most of the sampled households (regardless of household head sex, education and employment status) were food insecure according to this scale. That said, male, formally educated, or employed household heads seemed to be more likely to be food secure than household heads that were female, not formally educated, or unemployed.

Table 2. Frequency Distribution of Independent Variables Against the Household Food Insecure Access Prevalence (HFIAP) Scale.

The odds ratio calculations of the independent variables in this investigation against the HFIAP dependent variable also demonstrated some interesting findings (). Female-headed households had greater odds of being food insecure when compared to male-headed households. The same was true of those household heads without formal education or employment. Household heads without formal education had greater odds of being food insecure (when compared to formally educated household heads) and unemployed household heads had greater odds of being food insecure (when compared with employed household heads). These odds ratio calculations demonstrated a statistically significant relationship according to the Pearson’s chi-square tests of independence (at an alpha of 0.01).

Table 3. Odds Ratio Calculations of Independent Variables Against the HFIAP.

4.2. Research Objective Two results

When the odds ratios calculated in are adjusted for the influence of all independent variables in this investigation (using maximum likelihood estimation via binary logistic regression), the relationship between the sex of the household head and the food security status of the household changes (). When controlling for the education level and employment status of the household head, the predictive relationship between the sex of the household head and the food security status of the household becomes statistically insignificant (at an alpha of 0.05). That said, even while controlling for the influence of all independent variables in this investigation, the predictive relationship between the education level and employment status of the household remains statistically significant (again at an alpha of 0.05).

Table 4. Adjusted Odds Ratio (O.R.) Calculations Against the HFIAP using Binary Logistic Regression Analysis (n = 1754).

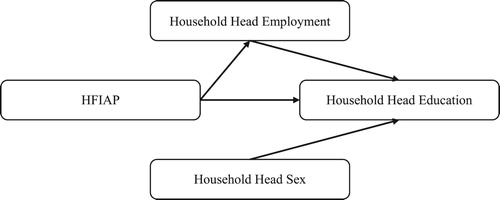

The relationships indicated in are confirmed graphically by the Bayesian Network in . This Bayesian Network demonstrates that, among the sampled households, the relationship between the sex of the household head and the food security status of the household is conditionally dependent on the education level of the household head. Furthermore, the relationship between the sex of the household head and the employment status of the household head is also conditionally dependent upon the education level of the household head (among the sampled households).

Figure 1. Bayesian Network of Conditionally Dependent Relationships Between Investigation Variables (n = 2,071).

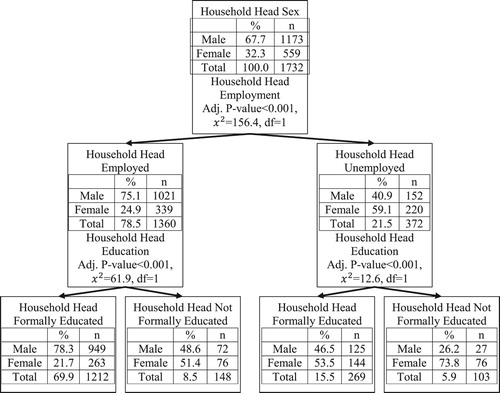

The CHAID decision tree depicted in provides some insight into why these conditionally dependent relationships might exist. Among those sampled household heads who were unemployed and had no formal education, 74% were female. At the same time, the opposite trend also existed among surveyed households. Among those sampled household heads who were employed and had a formal education, 78% were male. This decision tree depicts the gendered distribution of households based on education and employment among the surveyed households in Maputo. The CHAID decision tree learning algorithm was also implemented with the ward locations of households included as an additional independent variable and the structure of the tree remained unchanged.

5. Discussion

The findings in this analysis demonstrate that there is a statistically significant and predictive relationship between the sex of the household head and the food security status of the household among the surveyed households in Maputo. That said, this relationship appears to be conditionally dependent upon the education level and employment status of the household head. The distribution of education and employment across the sampled household heads also appears to be strongly gendered among the sampled households. Unsurprisingly, the data shows that the sex of the household head is a predictor of household food insecurity among the surveyed households. The data goes further in demonstrating that factoring in the education and the employment status of the household head reduces the food security gap between male-and female-headed households. This finding adds additional weight to the central importance of gender equality as a development goal by suggesting that the provision of educational and employment opportunities to women on par with men may be an important factor in household food security initiatives. Together, these findings suggest that the food insecurity of female-headed households may be partially explained by the inequitable distribution of education and employment across male and female-headed households in Maputo.

The findings from this investigation provide new quantitative evidence of the strong association between gender and food security in Maputo. A comparison of food security by gender and education of household head in Maputo and Nanjing, which used the same HCP dataset with a different analytical approach, suggested that the level of education is more of an equalising factor in Maputo than in Nanjing (Riley & Caesar, Citation2018). Possible reasons for different effects of gendered education levels on household food security include the differences in household formation and differences in gender dynamics in urban labour markets (Riley & Caesar, Citation2018). Comparisons in urban communities that are more culturally and economically similar to Maputo are needed to determine the extent to which these findings are applicable beyond this case study. For urban food security researchers and policymakers, this paper contributes to the understanding of the demographic predictors of food insecurity in Maputo. The data shows a continuity in the history of gender inequality shaping education and employment opportunities in Maputo while providing evidence of the extent to which other growing urban challenges (like food insecurity) may be dependent upon the distribution of these opportunities.

In sum, these findings help to explain the gendered effects underlying food insecurity suggested by a diverse literature including statistical models, historical research, and ethnographic observation. That said, these findings should be interpreted in light of both the limitations and strengths of the methods used in this investigation. While it is not possible to infer any generalisable causal mechanisms based on this research, these findings indicate the broader nuance underlying the gendered impacts of food insecurity in Maputo by identifying the nuanced system of relationships inherent in this association. The remaining discussion highlights the policy dimensions of the issues raised, drawing attention first to legislation toward gender equity in education and second to policies aimed at gender equity in employment.

Article 88 of the Constitution of the Republic of Mozambique stipulates the right to education for all Mozambican citizens and Article 122 promotes the development of women in social, cultural, political and economic spheres of activity (Mario & Nandja, Citation2006; Tvedten et al., Citation2008). The government of Mozambique has also implemented the 2001–2005 Action Plan for the Reduction of Absolute Poverty (PARPA, and later the 2006–2009 PARPA II), Law 6/92, and the 2000–2004 programme aimed at bolstering access to education as a means of combating poverty and to reinforce the political and economic model presented in the 1990 constitution (Mario & Nandja, Citation2006; Tvedten et al., Citation2008). These significant legislative instruments, which work in concert with global efforts to promote education for women and girls, have been slow to transform the gender-based inequalities observed in this study. While public education is centrally planned and managed (Roby et al., Citation2009; Tvedten et al., Citation2008), a sensitised municipal leadership could help to facilitate access to formal education by improving public transportation, utilities at schools (with sanitation services especially important for adolescent girls), and public safety in and around schools.

Gender roles also shape engagement in sectors of employment. At the national level, women have a greater participation in agriculture and a growing representation in the informal sector in Maputo (Agadjanian, Citation2002; MEF, Citation2016; Tvedten et al., Citation2008). The gender distribution across these employment sectors continues to place women in less profitable work and may hamper entry into more lucrative occupations. Nonetheless, the findings suggest that even part-time, informal, and low-paid employment is associated with improved household food security. While the long term strategic vision for gender equality with food security hinges on investments in education and public awareness of the need for cultural change, in the short term the municipality should be supporting female entrepreneurship in Maputo’s informal economy with an aim to improving household food security. Examples of policy measures include providing greater access to credit and protection from harassment during business hours.

This research has some important limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting its implications and significance. The thresholds that were set when binning the variables were meant to aid the odds ratio calculations and, potentially, assist with interpretability. That said, the way in which these variables were binned could have masked other more significant thresholds when categorising households according to their food security status. Given the limited availability of relevant census information (and the lack of list-frames and area-frames), the household survey of Maputo may not be representative. As a result, further research will be needed to verify whether the relationships observed in this paper are reproducible and generalisable. It is also important to note that no causal interpretations of the findings in this paper can be made exclusively based on the methods used in this investigation. Finally, there was a slight imbalance in the dependent variables used for the logistic regression analysis, Bayesian Network, and CHAID decision tree built in this investigation. That said, this imbalance was not significant enough to benefit from misclassification costs and resampling had the potential to change probabilities of inclusion for the sampled households in this survey. While there may have been too few wards sampled to support reliable multi-level regression modelling (Maas & Hox, Citation2005), future research should explore the extent to which the spatial distribution of the included indicators may have influenced these research findings.

There are other limitations related to the application of quantitative methods to the broader issue of gender and development. This is partly due to the obscurity of emic explanations for the configuration of households in Maputo and the gendered meanings associated with the sex of individuals recorded in the survey instrument. The scope of the article is limited to the questions that can be addressed with the data available. Related research on gender and urban food security in Southern Africa demonstrated the potential for complementary qualitative research to shine light on the complex interaction of identities, individual agency, economic and environmental conditions, and social trends in shaping the relationship between gender and urban household food security (Riley & Legwegoh, Citation2018). One notable omission from this analysis that was raised by Riley & Legwegoh (Citation2018) was the distinction between, on the one hand, female headed households with multiple women sharing caregiving and income generating roles, and on the other hand single women dividing their time and energy among multiple responsibilities. The male-headed/female headed binary could overstate the association of women with food insecurity since the female headed household category includes a higher proportion of households relying on one person to earn income and provide care.

The hazard of food insecurity in Maputo is often framed according to broader structural factors. The food sold in both formal and informal markets across the city is supplied through either local production (via the city’s green belt) or imports from South Africa, Swaziland and other international markets. Maputo’s reliance on international food imports is often highlighted to explain volatile food prices and household food insecurity in the city. This investigation, however, relied on household survey data, to explain the extent to which the relationship between the sex of the household head and food insecurity appears to be conditionally dependent upon employment and education. The paper thereby demonstrated that gender inequalities in food security are also an issue that policy makers should pay attention to. Many women in Maputo have limited access to education as are often prevented from entering the city’s labour market. As a result, this paper suggests that other public services (like education and employment assistance) may reduce the gender disparities in household food security in Maputo. This paper highlights the importance of bolstering the access to education and employment among female household heads in the city.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors of this manuscript are neither involved in nor affiliated with any organisations or entities that have either a financial or non-financial interest in the research presented in this manuscrip.

Funding Detailst

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada under grant number 895-2013-3005 and the International Development Research Centre under grant number 107775-001.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the support of the following: the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for the Hungry Cities Partnership.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This manuscript has been derived from an earlier discussion paper that was written by the authors for the Hungry Cities Partnership (McCordic et al., 2018). All requisite permissions to support the publication of this manuscript have been obtained.

References

- Agadjanian, V, 2002. Men doing “women’s work”: masculinity and gender relations among street vendors in Maputo, Mozambique. The Journal of Men’s Studies 10(3), 329–342.

- Battersby, J, 2012. Beyond the food desert: finding ways to talk about urban food security in South Africa. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 94, 141–159.

- Chant, S, 2013. Cities through a ‘gender lens’: A golden ‘urban age’ for women in the global south? Environment & Urbanization 25(1), 9–29.

- Coates, J, Swindle, A & Bilinsky, P, 2007. Household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: indicator guide. Version 3. USAID, Washington.

- Dodson, B, Chiweza, A & Riley, L, 2012. Gender and food insecurity in Southern African cities. AFSUN Food Security Series No. 10. AFSUN, Cape Town.

- Frayne, B, Crush, J & McCordic, C, eds., 2018. In Food and nutrition security in Southern African cities. Earthscan/Routledge, New York.

- Garrett, JL & Ruel, MT, 1999. Are determinants of rural and urban food security and nutritional status different? some insights from Mozambique. World Development 27(11), 1955–1975.

- Haddad, L, Hoddinott, J & Alderman, H, 1997. Intrahousehold resource allocation in developing countries. IFPRI, Baltimore.

- Maas, CJ & Hox, JJ, 2005. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences 1(3), 86–92.

- Mario, M & Nandja, D, 2006. Literacy in Mozambique: education for all challenges. UNESCO, Paris.

- McCordic, C, 2016. Urban infrastructure and household vulnerability to food insecurity in Maputo, Mozambique. PhD thesis, University of Waterloo.

- McCordic, C, 2017. Household Food Security and Access to Medical Care in Maputo, Mozambique. HCP Discussion Paper No. 7. Hungry Cities Partnership, Waterloo.

- Ministry of Economy and Finances, 2016. Poverty and well-being in Mozambique: Fourth national assessment of Budget Headcount – IOF 2014-2015. MEF, Maputo.

- Moser, C, 2017. Gender transformation in a new global urban agenda: challenges for habitat III and beyond. Environment and Urbanization 29(1), 221–236.

- Pitcher, MA, 2002. Transforming Mozambique: The politics of privatization, 1975-2000. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Quisumbing, A, Brown, L, Feldstein, H, Haddad, L & Peña, C, 1995. Women: The key to food security. IFPRI, Washington, DC.

- Raimundo, I, 2010. Gender, choice and migration: household dynamics and urbanisation in Mozambique. PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Raimundo, I, Crush, J & Pendleton, W, 2014. The state of food insecurity in Maputo, Mozambique. Urban Food Security Series No. 20. AFSUN, Cape Town.

- Riley, L & Caesar, M, 2018. Urban household food security in China and Mozambique: a gender-based comparative approach. Development in Practice 28(8), 1012–1021.

- Riley, L & Hovorka, A, 2015. Gendering urban food systems across multiple scales. In H De Zeeuw & P Drechsel (Eds.), Cities and agriculture: developing resilient urban food systems (pp. 336–357). Routledge, New York.

- Riley, L & Legwegoh, A, 2018. Gender and food security: household dynamics and outcomes. In B Frayne, J Crush & C McCordic (Eds.), Food and nutrition security in Southern African cities (pp. 86–100). Earthscan/Routledge, New York.

- Roby, J, Lambert, M & Lambert, J, 2009. Barriers to girls’ education in Mozambique at household and community levels: An exploratory study. International Journal of Social Welfare 18, 342–353.

- Ruel, MT, Garrett, JL, Morris, SS, Maxwell, D, Oshaug, A, Engle, P, … Haddad, L, 1998. Urban challenges to food and nutrition security: a review of food security, health, and caregiving in the cities. FCND Discussion Paper No. 51. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

- Sahn, DE & Alderman, H, 1997. On the determinants of nutrition in Mozambique: The importance of age-specific effects. World Development 25(4), 577–588.

- Tvedten, I, Margarida, P & Montserrat, G, 2008. Gender policies and feminisation of poverty in Mozambique. Report 2008: 13. CMI, Bergen.

- Tvedten, I, Mangueleze, L & Uate, A, 2013. Gender, class and space in Maputo, Mozambique. Policy Brief 2. CMI Brief 12(7), 1–4.

- Urdang, S, 1983. The last transition? women and development in Mozambique. Review of African Political Economy 10(27-28), 8–32.