?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In global value research, Muslim-majority countries emerge not only as consistently more patriarchal but also as a rather homogeneous cultural cluster to that effect. We, however, know little about the variation within Muslim-majority countries in these values through comparative analysis of subnational units. This limits the possibility of identifying ‘localized pockets of transformation’ in support for gender equality in what the global research depicts as a relatively stagnate region. This manuscript is a first attempt at explaining the subnational variation in gender egalitarian values across Muslim-majority countries and its effect on key individual-level variables like gender. We model province and individual-level variance across 64 provinces in Egypt, Iran and Turkey with multilevel analysis (Hierarchical Linear Modeling HLM 7.0). Results show that whether provinces are more urban positively influences gender egalitarian values. At the individual level, we find that whether provinces are more urban has the most powerful impact on unmarried women in increasing support for gender equality. Based on the results, we conclude that research must pay greater attention to the local contexts in which Muslim women are embedded, like their provinces, in terms of the opportunities they create outside of the ‘marriage market’ and the implications for their support of gender equality.

Introduction

The challenge of a Islamic religious heritage to democracy occupies many in the research on religious legacies and democratization around the world (see for instance Alexander & Welzel, Citation2011a; Fish, Citation2002; Gellner, Citation1994; Inglehart & Norris, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2005; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2002, Citation2004; Welzel, Citation2013; Yuchtman-Yaar & Alkalay, Citation2007). The bulk of this research uses global comparisons across countries to evidence a deep value divide between the Muslim world and the West. In much of this research, gender equality is seen as central to the puzzle of an Islamic religious heritage and the region’s lag in democracy (Fish, Citation2002; Inglehart & Norris, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Moaddel, Citation2006).

Indeed, in their path-breaking work on gender egalitarian values and value change, Inglehart and Norris (Citation2003a, Citation2003b) note that the most basic cultural fault line between the Western and Islamic countries concerns issues of gender equality. Following the work of Inglehart and Norris, additional evidence from public opinion research overwhelmingly indicates that citizens of Muslim societies are significantly less supportive on issues related to gender equality than those living in Western, democratic countries (e.g.; Alexander & Welzel, Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Moaddel, Citation2006; Welzel, Citation2013).

While this literature has amassed convincing cross-national, global evidence of more pronounced patriarchal values in Muslim-majority countries, there is a tendency to potentially overstate the cultural homogeneity in patriarchal values and institutions across these countries. Among these studies, the interpretation of the data emphasizes a rather uniform, stagnate context of patriarchy, which implies that processes that compete with and challenge traditional doctrine and practice potentially have little transformative power within these countries.

Contrary to this portrayal, some cross-national research offers counter evidence demonstrating significant variation across Muslim-majority countries in democratization (Robinson, Citation2006) and patriarchy (Rizzo, Abdel-Latif, & Meyer, Citation2007; Ross, Citation2008). Similarly, a bulk of qualitative research supports key differences in patriarchal beliefs and practices across Muslim-majority countries, within these countries and overtime (Charrad, Citation2011; Keddie, Citation2007; Kelly & Breslin, Citation2010; Moghadam, Citation2003a).

This disparity in perspectives calls for new evidence and approaches for assessing diversity in patriarchal values in the Muslim world. One new avenue for such assessment is subnational analysis of public opinion. The variations in patriarchal values in Muslim-majority countries have not been properly assessed from a subnational perspective with public opinion data.

This neglect of the subnational-level limits the possibility of identifying ‘localized pockets of transformation’ in support for gender equality in what some of the literature portrays as an otherwise relatively stagnate cluster of countries. Identifying such variation could lend deeper insights into drivers of change in spaces characterized by otherwise deeply rooted, patriarchal path-dependencies. According to Walby (Citation1989, p. 214) ‘patriarchy is a system of social structures and practices in which men dominate, oppress and exploit women.’ As Moghadam (Citation2003a, pp. 126–127) notes, the patriarchal contract in Muslim-majority countries finds its most basic roots within the family and household structures. Households are ultimately embedded in local, communal spaces. Therefore, their structural transformation and the transformation of patriarchal relations within them will be most sensitive to pockets of transformation occurring in wider local contexts. Subnational analysis of public opinion allows us to look closer at that interplay between diverse local contexts and patriarchy.

This manuscript is a first attempt at explaining the regional variation in Muslim-majority countries in gender egalitarian values. Using data from the World Values Surveys (WVS), we use the variable, ‘place of residence,’ to model variation in subnational units across Egypt, Iran, and Turkey. We also draw on various sources, including reports of 2005, 2006, and 2008 censuses for subnational data from the three countries. With these data, we model aggregate and individual-level variance across 64 Muslim-majority provinces with multilevel analysis using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM 7.0).

At the aggregate level, we look in particular at the influence of whether a province is more urban on gender egalitarian values. We theoretically motivate this factor based on a larger literature on subnational variation in gender equality in developing countries as well as qualitative literature on subnational variation in gender equality in Muslim-majority countries. At the individual level, we build off studies of individuals in Muslim-majority countries that find that women are more supportive of gender equality. We also investigate how the relationship between being female and support for gender equality varies by whether a province is more urban.

Literature review

The assumption of Islamic homogeneity and its critics

A tradition of scholars in political culture research have argued that nations clump together in larger socio-cultural units labeled ‘cultural zones’ or ‘civilizations’ and that nations belonging to the same zones or civilizations tend to share similar values and institutional traditions (Eisenstadt, Citation1986; Gellner, Citation1994; Huntington, Citation1996; Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2005 Weber, Citation1958;; Welzel, Citation2013). Under these perspectives, ultimately, civilizations constitute cultural zones of supranational diffusion that homogenize regions along similar patterns of deeply held beliefs and, in turn, send regions on their own particular trajectories in societal development and values.

Of all the factors in this tradition of research, religion is highlighted as one of the central defining characteristics of cultural zones or civilizations. Building on religion, scholars of this tradition assess the fault lines along which civilizations diverge most and potentially clash. Repeatedly, countries that share an Islamic religious legacy are considered most at odds compared to those with Western legacies (Eisenstadt, Citation1986; Gellner, Citation1994; Huntington, Citation1993, Citation1996; Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2005; Weber, Citation1958; Welzel, Citation2013).

(Inglehart and Norris (Citation2003a, Citation2003b) position gender center stage in this literature when they show that patriarchal values are a central factor driving the value divide between the Muslim world and the West. Indeed, Inglehart and Norris (Citation2003a, Citation2003b) introduce patriarchal values as the source of Islamic exceptionalism and the lag in democratic institutionalization in the region. Their research shows that while Islamic populations largely support democratic procedures for authorizing and holding accountable political leaders, they are not supportive of gender equality. While Inglehart and Norris offer an important and, for our purposes, key qualification in the Islam and democracy debate, they continue with an assumption that carries through the larger cross-national literature on which they build: an Islamic heritage powerfully homogenizes gender value systems as patriarchal across nations and subnational space.

While the perspective of a more monolith Muslim world is rather established in the above cross-national literature, a group of alternative cross-national studies dispute the monolithic portrayal, offering evidence, instead, of significant variation across Muslim-majority countries in democratization (Stephan and Robertson Citation2003) and patriarchy (Rizzo et al., Citation2007; Ross, Citation2008). This research demonstrates variation in Arab compared to non-Arab Muslim-majority countries and by level of oil production among Muslim-majority countries.

In addition, several qualitative studies challenge monolithic cultural representations of the Muslim world with a rich set of ethnographic findings that demonstrate differences in patriarchal beliefs and practices across Muslim-majority countries, within these countries and overtime (Abu-Lughod, Citation1998; Al-Ali, Citation2000; Charrad, Citation2011; Hoodfar & Sadeghi, Citation2009; Kandiyoti, Citation1988, Citation1991; Keddie, Citation2007; Kelly & Breslin, Citation2010; Moghadam, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Singerman, Citation1995; Tohidi, Citation2003). For instance, in Charrad’s (Citation2011, p. 418) overview of critiques of Islamic exceptionalism in the field, she notes that scholars (1) underscore the diversity of interpretations within Islamic tradition, (2) show considerable variation in the extent to which Middle Eastern states define gender ideology and enact policies that affect women, and (3) evidence different forms of women’s agency either through formal organizing or resistance in everyday life.

These alternative sets of evidence suggest a more nuanced view of the diversity of values within Muslim-majority countries. One strategy for building on this evidence base is expanding the research to analysis of public opinion at the subnational level. This expands the possibility of identifying ‘localized pockets of transformation’ in support for gender equality in what some of the literature portrays as an otherwise relatively stagnate cluster of countries. With its roots in household structures and family relations, patriarchy is a practice that impacts individuals’ everyday lives, in communal, grassroots’ spaces (Moghadam Citation2003a, pp. 126–127). Ultimately, these spaces are local. Thus, the factors that can potentially permeate and create pocketed erosion in support for patriarchy are likely to also be most effective and observable among these wider local contexts. From this perspective, focusing on the national level to understand variation in patriarchal attitudes is rather imprecise. Instead, subnational analysis of public opinion is a more precise option because this gives us a closer look at that interplay between diverse local contexts and patriarchy.

In the following section, we turn to the literature on the individual-level and within country factors that influence gender equality in Muslim-majority countries. According to our review of the literature, gender on the individual-level and whether spaces are urban on the macro-level emerge as key factors.

Theorizing drivers of ‘Localized Pockets of Transformation’: the role of women and urban spaces

Gender is an important individual-level variable in the literature on support for gender equality in Muslim-majority countries. Alexander and Welzel (Citation2011a) find that women are significantly less supportive of patriarchy than men are when comparing attitudes among Muslims in Muslim-majority countries. Moreover, Charrad (Citation2009, p. 546) notes that ‘Starting in the 1970s and continuing to the present, a rich literature has argued that as elsewhere in the world, Muslim women have not only resisted subordination but have actively shaped their own destiny.’ Along these lines, Moghadam (Citation2004, p. 13) shows that Islamic feminists condemn women’s placements in subordinate positions in Muslim-majority countries and criticize discriminatory structures in the family, economy and law. There is also evidence of Muslim women engaging in feminist reinterpretations of the Qur’anic verses that strive to deconstruct the links between Islam and discrimination against women (Moghadam, Citation2004, pp. 13–14; Wadud, Citation1999, Citation2006). In some cases, these women argue that the religious texts actually prescribe gender egalitarianism (e.g. Abu-Ali & Reisen, Citation1999).

The evidence also suggests that these critical views and reinterpretations mobilize women in the region. According to Moghadam (Citation2004, p. 15) this ‘has led to the formation of a women’s movement consisting of women’s organizations and groups of activists that utilize a variety of discursive and political strategies towards women’s inclusion, equality, and empowerment, as well as overall social change.’ Indeed, Moghadam describes vast proliferation in several types of women’s organizations beginning in the 1990s across the Arab/Middle Eastern region (Moghadam, Citation2004, p. 51).

The above research describes the rise and impact of women as transformative agents across Muslim-majority countries. Cross-national research has identified this gender difference, but confirms this only at the individual-level (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2011a). However, one could imagine more nuanced processes behind this transformative agency when considering the local contexts in which women are embedded across these countries and the heightened implication of local contexts for affecting the organization of households and patriarchal relations within them. Indeed, alluding to this, Charrad (Citation2011, p. 425) notes ‘women’s activism in the region can only be understood in localized, contextualized terms.’ Such nuance potentially goes lost under cross-national approaches. This begs the following question: What subnational processes likely drive women’s empowerment and their greater support of gender egalitarian values?

The literature on the effects of more urban environments suggests that whether a space is urban is a key aspect of variation across regions within countries that potentially increases support for gender equality and female empowerment. This literature generally considers urban spaces as dynamic and progressive compared to rural spaces (Simmel, Citation1971; Tönnies, Citation1963). This has positive implications for gender equality (Evans, Citation2015). Recent cross-national research, particularly focused on the developing world, associates urbanization with multiple gender egalitarian outcomes (Evans, Citation2015). This includes greater support for gender equality among young women (Boudet, Petesch, Turk, & Thumala, Citation2012), less justification for violence against women (Uthman, Lawoko, & Moradi, Citation2009), higher rates of later female age of marriage (World Bank, Citation2014, p. 110), higher rates of later age of pregnancy (UNFPA, Citation2007, p. 28), greater access to sexual and reproductive health services (UNFPA, Citation2007, p. 28), less support for female genital cutting (UNICEF, Citation2013), higher rates of education among girls (Lloyd, Citation2005, p. 78), less gender bias in household spending on education (Mussa, Citation2013), greater participation of women in household decision-making (Head, Yount, Hennink, & Sterk, Citation2015), and smaller gender gaps in education (Zeng, Pang, Zhang, Medina, & Rozelle, Citation2014).

In research focused on Muslim-majority countries in particular, evidence from ethnographic studies and case studies shows strong support for the positive influence of more urban spaces on gender equality. Moghadam (Citation2003a, p. 69) highlights this when arguing that in a patriarchal context, such as that found in Muslim-majority countries, women’s status is especially likely to vary by location: ‘Women certainly have more options in an urban setting, whereas in rural areas patriarchal family arrangements limit their options.’ Indeed, according to Moghadam (Citation2003a, p. 143) in more urban settings in the Middle East, local spaces are subjected to the impact of ‘capital penetration, infrastructural development, legal reform, mass education and employment’ which are the material bases under which ‘classic patriarchy crumbles’.

One of the key mechanisms through which ‘the crumbling of patriarchy’ occurs is through a restructuring of households from patrilineal to neolocal residences (Kandiyoti, Citation1988; Moghadam, Citation2003a). Extended patrilineal households ultimately operate through male kinship bonds, under which the senior male has control over all others and women’s status is severely subordinated for the purposes of kin reproduction (Kandiyoti, Citation1988, p. 278; Moghadam, Citation2003a, p. 119). Women are ultimately seen as property of the patrilineal kinship group and their production value is ultimately tied to their capability to ‘produce’ male children. This severely limits their status and value within the patrilineal extended household (Moghadam, Citation2003a, p. 119). Restructuring from patrilineal to neolocal households reduces the importance of elders and the strength of kinship bonds. What was a larger, rigid hierarchical system dependent on kinship replacement for survival of the household decentralizes into smaller units of household arrangements with less reliance on kinship replacement. Under such household restructuring, opportunities then emerge for women to become more autonomous and less reliant on extended kin, marriage and childbearing for security over their lifecycles. This tends to result in important demographic changes for female autonomy such as lower fertility rates, higher age of first marriage for women, and greater female access to education, all of which slowly erode support for patriarchy (Moghadam, Citation2003a).

To summarize, from this review of the literature, we derive four expectations to develop hypotheses. First, there is reason to believe that attitudes vary subnationally across Muslim-majority countries. The literature shows that subnational analysis of public opinion in Muslim-majority countries is a neglected area of research and an important strategy for building on research to understand what influences intra-regional variation in patriarchal beliefs and practices in the Muslim world. Second, individual-level evidence suggests that women will be more open and influenced in their support for gender equality attitudes compared to men in Muslim-majority countries. Third, whether a space is urban is a key subnational factor as more urban spaces have been linked to more support for gender equality. From these expectations, we derive four hypotheses.

H1: Gender egalitarian values will vary within and between provinces in Muslim-majority countries.

H2: Women are more supportive than men of gender egalitarian values.

H3: Respondents in provinces that are more urban are more supportive of gender egalitarian values.

H4: The relationship between being female and support for gender egalitarian values is stronger among respondents in provinces that are more urban.

Research strategy

This article explores differences in respondents’ support for gender egalitarian values within three Muslim-majority countries examined in the World Values Surveys (WVS) between 2006 and 2007. We sample 64 provinces across Egypt, Iran and Turkey.

Due to the difficulties in collecting province-level data in Muslim-majority countries (see Moghadam, Citation2003a, pp. 44–45 for a discussion of similar difficulties encountered in ethnographic research), we are limited to selecting a manageable, smaller sample of countries among those that have been surveyed in the fifth wave of the WVS. We choose Egypt, Iran and Turkey for the following reasons. First, in the most recent classification of countries into cultural zones with WVS data, Welzel (Citation2013) places all three of these countries in the Islamic East cultural zone, which the data show is by far the most patriarchal of all cultural zones. In this case, based on the data, these countries appear to share a uniformly high patriarchal value climate. They are therefore least likely cases for observing sub-national variation and therefore particularly critical for testing this theory. In addition, they are the largest countries in terms of population size in comparison to the other Muslim-majority countries placed in this cultural zone: Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco and Saudi Arabia. Given their size, we can expect more subnational variation, particularly in terms of populations living in urban compared to rural spaces. Finally, Egypt, Iran and Turkey are also some the most frequent cases on which much of the ethnographic research on Muslim-majority countries that we have cited are based. Thus, this gives us good reasons to expect the theory to match the data. We admit, however, that such a small sample of countries is an important limitation to our research. Future research that expands the number of cases with subnational data is needed to substantiate the generalizability of these results.

On the province-level, our sample includes 22 provinces in Egypt, 30 in Iran, and 12 in Turkey. On the individual-level, we have over 5,000 respondents nested in the 64 provinces that compose our sample. Appendix A displays the provinces by number of respondents.Footnote1

The survey data come from the fifth wave of the WVS, which is a large-scale quantitative survey administered between 2005 and 2009 across the globe. In each country of the WVS, a representative random probability sample was drawn with strict quality controls employed to ensure that all three national samples met the requirements for representativeness. Wave 5 of the WVS contained a module on gender attitudes and the variable, place of residence, comprising of information on views of gender equality and place of living at the province level. This makes the questionnaire particularly suitable for our purposes. Given our interest in the literature on Muslim identification and patriarchal values, we include only Muslim respondents. All other cases were excluded from the analysis. Correspondingly, the very few cases among the non-Muslim within the Turkish (1 case, 0.1% of total sample), Iranian (23 cases, 0.8% of total sample) and Egyptian (195 cases, 6.4% of total sample) sample were excluded.

With this sample, we develop cross-level models based on predictors from previous studies and our above presented hypotheses. We combine province-level and individual-level data into hierarchal linear models to explain support for gender egalitarian values across our sample of 64 provinces. The models are analyzed with HLM 7.0.

Data

As our dependent variable, we work with a composite index of questions that measure respondents’ support of gender equality across three categories: political leadership, business leadership and labor force participation. The questions ask respondents whether (1) ‘men make better political leaders than women do’; (2) ‘when jobs are scarce a man has more right to a job then a girl’; and, (3) ‘men make better business executives than women do.’Footnote2 For question one, on leaders, and three, on business executives, respondents could answer (1) strongly agree, (2) agree, (3) disagree or (4) strongly disagree. For question two, on jobs, respondents could answer (1) agree, (2) neither or (3) disagree. Ultimately, we combine the responses to these three items into one index to measure attitudes towards gender equality per respondent. We do this in the following way. First, we rescale responses to each single item so that they run from 0 to 1.0 and so that egalitarian responses are scored higher and traditional views lower. For example, for responses to the question on leaders, we rescale these so that a response of strongly disagree is scored 4 and a response of strongly agree 1. We then divide each response by the maximum possible score, in this case 4Footnote3, so that the response value ultimately runs between 0 and 1.0. Then, we add the scores per respondent for the three items, all ranging between 0 and 1.0. This gives us a score between 0 and 3 per respondent. From here, we divide each respondent's score by 3. This creates a scale per respondent that runs from 0-1.0 with lower scores indicating least egalitarian attitudes and a score of 1 indicating most egalitarian attitudes.

We introduce the following independent variables at the individual-level: sex, level of religiosity, age, marital status, education and income.Footnote4 For sex, female is coded 1 and male 0. For religiosity, we use a standard question in the WVS: ‘How important is God in your life?’. Then, respondents are given the option of placing themselves on a 10-point scale, where 10 means very important and 1 means not important. Age is measured as years since birth. Marital status is measured as 1 for unmarried and 0 for married. We measure education as an interval-like scale, by which 8 indicates the highest education level and 0 the lowest. Finally, with respect to income, respondents are asked to place themselves on a subjective income scale, from 1.0 for the lowest decile to 10.0 for the highest decile.Footnote5

Independent variables at the province–level

As in many other developing countries, Egypt, Iran and Turkey have incomplete subnational information. Nevertheless, we attempt to identify existing reliable sources on related province levels in which individuals in our sample are nested. To match the individual-level data to provinces, we use the WVS item called place of residence. These data used at the province level come from various sources. These include level of urbanization, infant mortality rate and average household size.

Level of urbanization is measured as the percent of the population living in urbanized areas in a province. The data for Egypt come from the Human Development Report in 2008 (based on the census of 2006), for Iran from the National Population and Housing Census in 2011 (based on the census of 2006)Footnote6 and for Turkey from the Turkish Health Statistics Yearbook in 2012. As province-level controls, we include a measure of human development and wealth. To proxy development, we use data on infant mortality rates by province, and to proxy wealth, we use data on average household size.Footnote7 The infant mortality rate is the number of deaths of infants under one year old per 1,000 live births. This was measured in 2005–06 for Egypt based on data from the Egypt Human Development Report (Citation2008). These data are also based on 2005–06 for Turkey and come from the Turkish Statistical Institute. These data for Iran are measured in 2005 based on the 2000 census. Average size of household is calculated as the average number of people (adults and children) per household for households of a given type by province. The data for Egypt and Iran refer to 2006 Census, and for Turkey to the 2004 Census.

Results

Model specification

To test our full set of hypotheses, we use the following formula:

Support for H1

H1 simply expects gender egalitarian values to vary within and between the 64 provinces. In this case, we run a reduced form of the formula above by running an intercept-only (or unconditional) model with HLM 7.0. Here, we run a restricted maximum likelihood estimation including only our individual-level dependent variable. In the final estimation of fixed effects with robust standard errors, the coefficient is 1.17 denoting the overall mean in support of gender egalitarian values and, with a p-value of ≤ .001, that this differs significantly from 0. With this result, we confirm H1, gender egalitarian values vary both within and between our 64 provinces.

Support for H2, H3 and H4

To test H2, H3 and H4, we introduce our full set of independent variables at the province and individual levels in the multilevel model in . H2 expects women to be more supportive than men of gender egalitarian values. H3 expects respondents in more urban provinces to be more supportive of gender egalitarian values. H4 expects the relationship between being female and support for gender egalitarian values to be stronger among respondents in provinces that are more urban.

Table 1. Explaining support for gender egalitarian values across provinces and individuals in Egypt, Iran and Turkey (MLM with HLM 7.0).

To be consistent with H2, at the individual-level, female should be positive and significant. To be consistent with H3, at the province-level, urban should be positive and significant. Finally, testing H4 requires cross-level modeling. Toward this end, we also include an interaction term between the measure of how urban a province is and female at the individual-level. To be consistent with H4, the interaction should be positive and significant.

reports the multilevel results of the final estimation of fixed effects with robust standard errors. Among the individual-level factors, female is positive and significant. This is consistent with H2. In addition to being female, respondents with lower levels of religiosity, unmarried, higher levels of education and higher income are also more supportive of gender egalitarian values. On the province-level, the measure of whether a province is more urban is significant and positive, which is consistent with H3. In addition to whether a province is more urban, larger average household size is positively and significantly related to support for gender equality values, and the measure of province-level infant mortality rates is negatively related to support for gender equality, but only approaches significance. Finally, the model in also includes a cross-level interaction term between urban and female. Consistent with H4, this interaction effect is positively related to support for gender equality values, however the variable just approaches significance at the p ≤ .08 level. In this case, there is some evidence for H4, that women’s support for gender egalitarian values compared to men is even stronger when they reside in a province that is more urban.

Given that the interaction only approaches significance, we were curious as to whether the effect among women was stronger if we considered additional information, such as age, marital status or education, and whether this differed from men. Thus, we test two new models, one for the female sample (n = 2805) and one for the male sample (n = 2623). In these models, we interact urban with religion, age, marital status, education and income.

reports the results from the model run over the female sample. Urban is positive and significant and only the interaction with marital status is positive and significant (p = .03). This result tells us that the relationship among women between being unmarried and support for gender egalitarian values is stronger in urban provinces.

Table 2. The cross-level effect of urbanization on women’s support for gender egalitarian values across provinces and individuals in Egypt, Iran and Turkey (MLM with HLM 7.0).

Interestingly, the same result does not hold for the male model. reports these results. The main effect of urban is significant, albeit weaker than in the female model, but the model contains no significant interaction. This suggests that a strong confirmation of H4 is conditional depending on whether we are looking at married or unmarried women. Whether a province is more urban significantly increases the relationship between being female and unmarried and support for gender egalitarian values. The same effect does not hold for men. Thus, in urban provinces unmarried women most strongly diverge from men in their support for gender egalitarian values.

Table 3. The cross-level effect of urbanization on men’s support for gender egalitarian values across provinces and individuals in Egypt, Iran and Turkey (MLM with HLM 7.0).

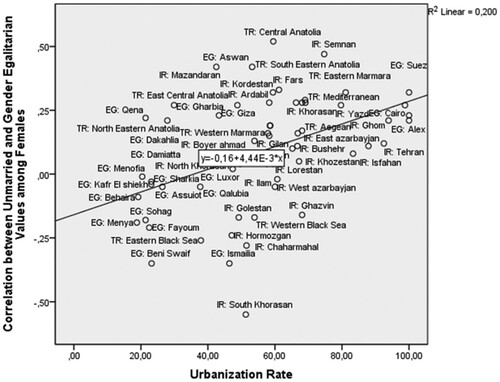

For illustrative purposes, plots the simple bivariate relationship between a province’s level of urbanization and the strength of the individual-level relationship between being unmarried and level of gender egalitarian values among the female sample. The correlation is positive with a Pearson’s r of .45 and significant at the p ≤ .001 level. Examples of provinces that are high in both indicators are Suez in Egypt, Ghom in Iran and Mediterranean in Turkey.

Discussion

Contrary to one of the stronger tendencies to portray Muslim-majority countries as a rather monolithic cultural space in global, cross-national research, our evidence supports a more dynamic picture of within country variation across provinces in Egypt, Iran and Turkey. According to the results, there is variation both between and within these provinces in support for gender egalitarian values. When we dig further, we find that whether provinces are more urban is a key macro-level variable that increases support for gender egalitarian values. On the individual-level, we reconfirm that women are more supportive than men and there is some evidence (significant at p = .08) of a cross-level interaction that denotes that in more urban provinces the positive relationship between being female and support for gender egalitarian values is stronger. Given that these results were somewhat weak, we looked closer at whether the effect among women was stronger if we considered additional information, such as age, marital status or education, and whether this differed from men. Moving in this direction, we found a significant cross-level interaction among women: the strength of the relationship between being unmarried and support for gender egalitarian values among individuals increases in more urban provinces. The same interaction did not appear when modeled across the male sample. In this case, whether provinces are urban has the most powerful impact on unmarried women in decreasing support for patriarchal values across the Egyptian, Iranian and Turkish provinces.

How might we understand this more nuanced result that underscores the interplay between urban spaces, marriage and female support for gender equality? Both Moghadam (Citation2003a) and Kandiyoti (Citation1988) note that in more rural spaces in Muslim-majority countries extended patrilineal networks are especially strong and, thus, women find security almost exclusively by entering into marriage and a strict system of patriarchy within the household. In this case, women develop patriarchal norms to prepare themselves for the marriage market, because this is a primary pathway to security over their adult lifecycles. Thus, whether they are married or not does not vary the level of their patriarchal orientations.

To the contrary, urban spaces tend to diminish the strength of patrilineal kinship bonds as the primary sources of security, generally, and marriage as the only option for security for women. In this case, women in urban spaces may adjust their expectations to the possibility of a more autonomous life particularly when they are unmarried, because this is a more viable option in this local space.

Other research on female public opinion in Muslim-majority countries lends support to this interpretation of the evidence. Blaydes and Lizner (Citation2008) explain support for fundamentalist beliefs among Muslim women in 18 Muslim-majority countries. As a subset of fundamentalist beliefs, they look at some of the same measures of patriarchal values that are the focus of our study. Similar to our findings, Blaydes and Lizner also find that unmarried Muslim women are least supportive of patriarchy. To explain this, they argue that support of fundamentalist values, like patriarchy, increases the appeal of women as marriage partners, and, therefore, if women lack opportunities that give them greater autonomy over their own security and development, such as economic opportunities, this pushes them into marriage as the only opportunity for achieving security over their lifetimes. Under such conditions, to appeal to the expectations of the ‘marriage market’, they adopt more fundamentalist values, among them support for patriarchy.

Blaydes and Lizner do not look at the subnational level and therefore do not consider the relevance of within country variation, like whether provinces are urban, that may create contexts where women are less dependent on marriage for security. However, our results support the idea that contexts that increase opportunities for Muslim women reduce their reliance on marriage as the primary source of personal security and growth, and this decreases their likelihood to support more patriarchal ideals, at least before they have married. Thus, in addition to thinking of the resources available to Muslim women at the individual-level, we must also consider the local contexts in which they are embedded, like their provinces, in terms of the opportunities they create outside of the ‘marriage market’ and the consequences for traditional patriarchal roles.

Conclusion

This manuscript is a first attempt at explaining the regional variation in gender egalitarian values across provinces in three Muslim-majority countries. We look at variation in individuals’ attitudes across 64 provinces in Egypt, Iran and Turkey. We use multilevel analysis to determine whether and how these values vary across this sample of provinces.

We derive and test four hypotheses based on various strands of literature including: (1) critiques of the global values and value change literature, (2) literature on individuals in Muslim-majority countries that find that women are more supportive of gender equality, and (3) literature on urban spaces in explanations of subnational variation in gender equality in developing countries and Muslim-majority countries. Based on this review, we expect gender egalitarian values to vary within and between the 64 provinces (H1), women to be more supportive than men of gender egalitarian values (H2), respondents in provinces that are more urban to be more supportive of gender egalitarian values (H3), and the relationship between being female and support for gender egalitarian values to be stronger among respondents in provinces that are more urban (H4). The evidence is strongly consistent with the first three hypotheses and, while weaker, consistent with the fourth hypothesis.

Given that the results in favor of the fourth hypothesis were somewhat weak, we looked closer at whether the effect of being in a more urban province on support of gender egalitarian values among women was stronger if we considered additional information, such as age, marital status or education, and whether this differed from men. Moving in this direction, we found a significant cross-level interaction among women: the strength of the relationship between being unmarried and support for gender egalitarian values increases under more urban provinces. The same interaction did not appear when modeled across the male sample. To interpret this result, we speculated that contexts, such as more urban spaces, increase opportunities for Muslim women. This, in turn, reduces their reliance on marriage as the primary source of personal security and growth, and thereby decreases their likelihood to support ideals that are more patriarchal before entering marriage.

Overall, these findings suggest that research on patriarchal values should move in the direction of subnational analysis. Subnational analysis of public opinion allows us to look closer at that interplay between diverse local contexts and patriarchy. If the patriarchal contract is ultimately rooted in the family and household than it is through this turn to more local units of analysis that we can more precisely understand processes behind its transformation.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful for the comments we recieved from participants of the Research Colloquium organized by Steffen Kuehnel at the Department of Sociology, Georg-August-university Goettingen. We would also like to thank Anne-Katrin Kreft for helpful feedback on an earlier draft.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amy C. Alexander

Amy C. Alexander is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Gothenburg University, Sweden. She is also a research fellow with the Quality of Government Institute under the Performance of Democracies Project at Gothenburg University.

Sara Parhizkari

Sara Parhizkari is a research associate at the Center of Methods in Social Science at the University of Goettingen.

Notes

1. The fewest respondents we have from a given province are 19 in one province in Egypt and 20 in three provinces in Iran and Turkey. Especially low numbers of groups within a level or as little as one observation for some groups are not worrisome from a statistical perspective (Gelman & Hill, Citation2007, p. 275).

2. We do not include an additional item that is typical of this kind of index construction using WVS data: “a boy has more right to a university education than a girl.” In comparison to the other items, support for more gender equality in education is much higher among our respondents. For instance, 30 percent of our respondents strongly disagree with this statement, compared to about 10 percent or less in response to the other items. In auxiliary analyses, we ran our final models with the education item included in the index and this only slightly changed the results. Rizzo et al. (Citation2007, p. 1158) also do not include the education item in their construction of a gender equality index for Muslim-majority countries.

3. For the question on jobs, the maximum score would be 3, so we divide by this to create a comparable 0 to 1.0 scale.

4. It would have been ideal to also introduce an individual-level variable on individual’s urban/rural residence. Unfortunately, the WVS did not ask for this demographic information in this wave.

5. We do not include an individual-level control for women’s labor force participation for the following reasons. Women’s labor force participation, either as employed full or part time, is low in Egypt, Turkey and Iran. Indeed among our sample of WVS respondents, women make up approximately 12 percent of full or part time employees in Egypt, Iran and Turkey. Furthermore, among those that have indicated full or part time work, the responses may be biased according to whether the women are engaging in paid labor or unpaid subsistence labor.

6. The urbanization rate of the province Tehran for 2006 has been calculated based on the provinces Tehran and Alborz for 2011.

7. We also acquired data that measures the equivalent of the UNDP’s Human Development Index across most provinces. This data does not cover all provinces. In addition, there was not much variation in this data across provinces with a mean of .71 and a standard deviation of .045. It is therefore less optimal compared to the infant mortality data. In auxiliary models including this variable instead of the infant mortality variable does not change the results.

References

- Abu-Ali, A., & Reisen, C. A. (1999). Gender role identity among adolescent Muslim girls living in the U.S. Current Psychology, 18(2), 185–192. doi: 10.1007/s12144-999-1027-x

- Abu-Lughod, L. (1998). Remaking women: Feminism and modernity in the Middle East. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Al-Ali, N. (2000). Secularism, gender and the state in the Middle East: The Egyptian women’s movement. Cambrdige: Cambridge University Press.

- Alexander, A. C., & Welzel, C. (2011a). Islam and patriarchy: How robust is Muslim support for patriarchal values? International Review of Sociology, 21, 249–276. doi: 10.1080/03906701.2011.581801

- Alexander, A. C., & Welzel, C. (2011b). Empowering women: The role of emancipative beliefs. European Sociological Review, 27(3), 364–384. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcq012

- Blaydes, L., & Lizner, D. A. (2008). The political economy of women's support for fundamentalist islam. World Politics, 60, 576–609. doi: 10.1353/wp.0.0023

- Boudet, A. M. M., Petesch, P., Turk, C., & Thumala, A. (2012). On norms and agency: Conversations about gender equality with women and Men in 20 countries. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Charrad, M. M. (2009). Kinship, Islam, or Oil: Culprits of gender inequality? Politics and Gender, 5, 546–553. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X09990353

- Charrad, M. M. (2011). Gender in the Middle East: Islam, state, agency. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 417–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102554

- Egypt Human Development Report (EHDR). (2008). Egypt's social contract: The role of civil society, Cairo.

- Eisenstadt, S. N. (1986). Introduction: The axil Age breakthroughs: Their characteristics and Origons. In S. N. Eisenstadt (Ed.), The origins and the diversity of axial Age civilizations (pp. 1–25). New York: SUNY Press.

- Evans, A. (2015). Urban Social Change and Rural Continuity in Gender Ideologies and Practices. University of Cambridge Working Paper.

- Fish, S. M. (2002). Islam and authoritarianism. World Politics, 55, 4–37. doi: 10.1353/wp.2003.0004

- Gellner, E. (1994). Conditions of liberty, civil society and its rivals. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Head, S. K., Yount, K. M., Hennink, M. M., & Sterk, C. E. (2015). Customary and contemporary resources for women's empowerment in Bangladesh. Development in Practice, 25(3), 360–374. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2015.1019338

- Hoodfar, H., & Sadeghi, F. (2009). Against All odds: The women’s movement in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Development, 52( 2), 215–223. doi: 10.1057/dev.2009.19

- Huntington, S. P. (1993). The clash of civilizations? Foreign affairs, pp. 22–49.

- Huntington, S. P. (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003a). Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003b). The true clash of civilizations. Foreign Policy 135(March/April), pp. 63–70.

- Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change and democracy. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with patirarchy. Gender and Society, 2, 274–290. doi: 10.1177/089124388002003004

- Kandiyoti, D. (Ed.). (1991). Women, Islam and the state. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Keddie, N. (2007). Women in the Middle East: Past and present. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kelly, S., & Breslin, J. (2010). Women’s rights in the Middle East and north Africa. New York: Freedom House.

- Lloyd, C. B. (Ed.). (2005). Growing up global: The changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Moaddel, M. (2006). The Saudi public speaks: Religion, gender, and politics. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 38(1), 79–108. doi: 10.1017/S0020743806412265

- Moghadam, V. M. (2003 [1993]a). Modernizing women. Gender and social change in the Middle East. Boulder, London: Lynne Rienner.

- Moghadam, V. M. (2003b). Is gender equality in Muslim societies a barrier to modernization and democratization? Paper prepared for the Center for Strategic International Studies, Washington, D.C. (July).

- Moghadam, V. M. (2004). Towards gender equality in the Arab/ Middle East region: Islam, culture, and feminist activism: A background paper for HDR, UNDP Human Development Report Office - occasional paper.

- Mussa, R. (2013). Rural–urban differences in parental spending on children's primary education in Malawi. Development Southern Africa, 30(6), 789–811. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2013.859066

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2002). Islam and the West: Testing the ‘Clash of Cvilizations’ Thesis. Faculty Research Working Papers Series, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, April.

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2004). Sacred and secular. Religion and politics worldwide. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Rizzo, H., Abdel-Latif, A.-H., & Meyer, K. (2007). The relationship between gender equality and democracy: A comparison of Arab versus Non-Arab muslim societies. Sociology, 41, 1151–1170. doi: 10.1177/0038038507082320

- Robinson, J. A. (2006). Economic development and democracy. Annual Review of Political Science, 9, 503–527. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.092704.171256

- Ross, M. (2008). Oil, Islam and women. American Political Science Review, 102, 107–123. doi: 10.1017/S0003055408080040

- Simmel, G. (1971). On individuality and social forms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Singerman, D. (1995). Avenues of participation: Family, politics and networks in urban quarters of Cairo. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Stephan, A. C, & Robertson, G. B. (2003). An ‘Arab’ more than a ‘Muslim’ democracy gap. Journal of Democracy, 14(3), 30–44. doi: 10.1353/jod.2003.0064

- Tohidi, N. (2003). Women’s rights in the Muslim world: The universal particular interplay. Haawwa: Women Middle East Islamic World, 1, 152–188. doi: 10.1163/156920803100420324

- Tönnies, F. (1963). Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft–Grundbegriffe der reinen Soziologie, Darmstadt.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2013). Female genital mutilation/cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. New York: Author.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2007). Growing up urban, state of world population 2007: Youth supplement. New York, NY: Author.

- Uthman, O. A., Lawoko, S., & Moradi, T. (2009). Factors associated with attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women: A comparative analysis of 17 sub-Saharan countries. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 9, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-14

- Wadud, A. (1999). Quran and women: Rereading the sacred text from a women’s perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wadud, A. (2006). Inside the gender jihad: Women’s reform in Islam. Oxford: Oneworld.

- Walby, S. (1989). Theorising patriarchy. Sociology, 23(2), 213–234. doi: 10.1177/0038038589023002004

- Weber, M. (1958). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. New York, NY: Scribners.

- Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising. Human empowerment and the quest for emancipation. Cambridge: Cambridge. University Press.

- World Bank. (2014). The world bank annual report 2014. Washington, DC: Author.

- Yuchtman-Yaar, E., & Alkalay, Y. (2007). Religious zones, economic development and modern value orientations: Individual versus contextual effects. Social Science Research, 36, 789–807. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.06.004

- Zeng, J., Pang, X., Zhang, L., Medina, A., & Rozelle, S. (2014). Gender inequality in education in China: A meta-regreession analysis. Contemporary Economic Policy, 32(2), 474–491. doi: 10.1111/coep.12006