ABSTRACT

How ambitious, active and influential are countries and regional groups in global environmental negotiations? We construct eight ideal types of their roles based on ambition, activity and influence. We then examine how the roles of countries and regional groups are perceived by participants in these negotiations through a large-scale online survey. The European Union, Norway and the African Group are perceived as the most prominent reformist leaders, being highly ambitious, active and influential. On the contrary, India, the Russian Federation and many regional groups are mostly perceived as conservative bystanders, with low levels of ambition, activity and influence.

Many environmental problems are global in nature and are addressed by states in multilateral negotiations taking place in international institutions and treaty regimes. In an attempt to increase their weight in such negotiations, many countries coordinate with like-minded countries within regional groups. Hence, international environmental negotiations are mostly conducted along the lines set out by major countries and regional groups. However, the academic literature on environmental negotiations still lacks a framework that captures the roles countries and regional groups play in international environmental negotiations. Most studies focus on the role of a single country, a single regional group or on leaders in environmental negotiations (see for example Bäckstrand and Elgström Citation2013; Oberthür and Groen Citation2017).

Against this backdrop, this article comprehensively examines the perceived roles of countries and regional groups in international environmental negotiations. It focuses on three dimensions of this role: the ambition of the position of countries and regional groups; their diplomatic activity; and their influence on the outcome of the negotiations. This three-dimensional role conception allows us to understand not only which countries and regional groups play a leadership role, but also what other roles exist in environmental negotiations. We particularly study how the role of countries and regional groups in international environmental negotiations is perceived. We therefore rely on a large-scale online survey with 659 country delegates who participated in the negotiations in three environmental forums in the period 2018-19. We focus on studying role perceptions, because the identity of countries and groups is constructed by their interactions with others (Lucarelli Citation2014).

Doing so, we address three shortcomings in the literature. First, the lion’s share of studies on actors in international environmental negotiations revolves around the concept of leadership (see for example, Bäckstrand and Elgström Citation2013; Liefferink and Wurzel Citation2017; Parker and Karlsson Citation2018; Parker et al. Citation2017). Whereas many studies identify leaders, they often do not distinguish among them or do not conceptualise the role of non-leaders in international environmental negotiations. Aiming to study roles in international environmental negotiations more comprehensively and without an exclusive focus on leaders, we develop a new typology of eight ideal-type roles and examine to what extent delegates to international negotiations attribute these role conceptions to countries and regional groups.

Second, the literature on the role of actors in international environmental negotiations is mostly based on actors’ own perceptions. Scholars rarely focus on how an actor is perceived by others. An exception are the studies by Charles Parker et al. (Citation2015) and Charles Parker and Christer Karlsson (Citation2018) dealing with actors’ recognition as leaders in climate change negotiations. Yet, although these two works deal with perceptions, they do not further identify what kind of leaders these countries are, nor do they address the role of non-leaders. This article therefore focuses on how the role of countries and regional groups is perceived by delegates who participated in international environmental forums and who witnessed the role played by the major countries and regional groups.

Third, the literature on actors in global environmental politics focuses to a large extent on climate negotiations (Parker et al. Citation2015; Wurzel et al. Citation2019; Parker and Karlsson Citation2018). Other environmental issues, such as the production and use of chemicals, the loss of biodiversity or air pollution are also important issues that are tackled globally. Nonetheless, they have received much less attention. The focus on climate in the literature on international environmental negotiations leaves other, less politicised, yet important domains of environmental policy comparatively understudied (Torney et al. Citation2018). Countering this bias in the literature, we examine role perceptions in three different environmental forums: the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) and the treaties on chemical and waste governance, that is the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm (BRS) Conventions.

Addressing these gaps in the literature, we explore the following research question: How do delegates to international environmental negotiations perceive the role of countries and regional groups in such negotiations? The perceived roles are examined through the dimensions of ambition, diplomatic activity and influence. These three role dimensions correspond to the main attributes of an international negotiation process: an actor starts negotiating with a particular ambition, then engages in diplomatic activities to convince others of that position in order to finally influence the negotiation outcome. We find that many survey participants perceive the countries and regional groups either with high scores on all three dimensions or with low scores on all three dimensions. Consequently, the most commonly perceived ideal types are what we will call a ‘reformist leader’ and a ‘conservative bystander’. The EU, Norway and the African Group are perceived as the most ambitious, active and influential actors (‘reformist leaders’). Conversely, many regional groups are mostly perceived as the least ambitious, active and influential actors (‘conservative bystanders’). However, the role of a number of countries (for example, India and the Russian Federation) is not perceived in the same way by all respondents, which might be related to the fact that the role of these countries vary depending on the issue under negotiation.

The article is structured as follows. The next section reviews the current literature on roles and perceptions in global environmental politics. The following section presents our typology of three-dimensional roles. The article then discusses the methodology and dataset. The next section presents the data and findings on the perceived roles of countries and regional groups in the three forums, followed by a conclusion.

International environmental negotiations: state of the art

This section reviews the literature on international environmental negotiations on which the construction of our typology of roles relies. We combine two streams of literature. First, by providing a new typology of roles in international environmental negotiations, we contribute to the scholarship on roles in global environmental politics. Second, we engage with the literature on perception and recognition, as our analysis is based on the perceptions of actors in international environmental forums.

Roles in global environmental politics: leaders, laggards and pushers

We consider roles as social positions and specific patterns of behaviour (Harnisch Citation2011; Holsti Citation1970; Elgström and Smith Citation2006). The literature on roles in global environmental politics has employed different concepts, such as leaders, laggards or pushers, to capture how states and groups behave in environmental negotiations. The most commonly used concept is leadership. A leader is typically defined as an actor who influences and mobilises followers for a purpose and has the power to orient them (Nye Citation2008; Underdal Citation1994). In the context of international negotiations, the concept of leadership was initially introduced to study regime formation: for example, Oran Young (Citation1991) and Joyeeta Gupta and Lasse Ringius (Citation2001) examined how actors contribute to the establishment of new international institutions. The literature distinguishes between three main types of leaders: structural, directional and instrumental (Gupta and Ringius Citation2001). Usually, the focus is exclusively on influential actors, and the leadership literature falls short of conceptualising the role of non-leaders during international negotiations.

Next to the leadership conceptualisation, several other concepts capture how public actors behave in global environmental politics. Trying to include non-leaders in their study, Steinar Andresen and Shardul Agrawala (Citation2002) differentiate between leaders, pushers and laggards. This conceptualisation has later been extended by Duncan Liefferink and Rüdiger Wurzel (Citation2017), who distinguish between four roles: laggards, pioneers, pushers and symbolic leaders. Further refining this conceptualisation, Rüdiger Wurzel et al. (Citation2019) argue that a substantive leader could act as either a constructive or a conditional pusher: the former unilaterally adopts ambitious policies, the latter requires others to adopt similar measures in order to be ambitious (8). Sebastian Oberthür and Lisanne Groen (Citation2017) propose yet another categorisation to examine actors who lead and actors who do not lead in a negotiation process: leaders, bystanders and mediators. A bystander is a non-active participant who does not exercise any influence on the negotiations, whereas a mediator actively searches for opportunities to build bridges and thereby increases its chances of being influential.

Taken together, the existing literature on roles in global environmental politics has mostly tried to describe leaders. In fact, non-leaders are more difficult to conceptualise, and the current literature offers a plethora of concepts that do not allow for a comprehensive analysis of the roles of all actors in international environmental negotiations. Therefore, we introduce a new role typology capturing ambition, diplomatic activity and influence. The typology ranges from the reformist leader, who is a highly ambitious, active and influential actor, to the conservative bystander, who is unambitious, inactive and uninfluential.

Role perceptions

In international environmental negotiations, several actors regularly claim a leadership position. However, it is unclear to what extent this leadership is recognised by other actors, because perceptions in international environmental negotiations are rarely studied. Moreover, the extent to which non-leading actors play important roles in these negotiations is even less addressed in the literature. So far, few studies have focused on assessing the perceptions of countries or groups in international environmental negotiations.

A prominent exception are the aforementioned studies by Charles Parker et al. (Citation2012; Citation2015), which identify perceived leaders in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations. They show that China, the US, the EU and the Group of 77 (G77) are most often regarded as leaders by delegates to the Conference of the Parties (COP) (Parker et al. Citation2015). At the 2015 COP, the US was the most recognised leader, assessed as such by 59 per cent of respondents, while China was recognised as a leader by 54 per cent of respondents, followed by the EU with 41 per cent (Parker and Karlsson Citation2018). Whereas the BASICFootnote1 countries and the Alliance of Small Island States are equally described as leaders, they are only recognised as such by about 10 per cent of respondents (Parker et al. Citation2015; Parker and Karlsson Citation2018). Charles Parker and Christer Karlsson (Citation2018) also find that the geographical origin of participants matters when assessing the leadership of countries and regional groups. For example, the US is firmly recognised as a leader by delegates from Europe and North America, yet much less so by African and Asian delegates.

Another exception examining perceptions is the study by Julia Gurol and Anna Starkmann (Citation2020), which assesses roles in climate negotiations. It finds that, whereas the EU is mostly perceived as an (inconsistent) leader, China is usually described as a rising power. Moreover, China regularly moves between different roles, strategically switching between a strong leader and a defender of the interests of developing countries.

These studies on perceptions provide empirical evidence to better understand environmental negotiations. However, they focus on the perceived role of specific countries or leaders and are limited to climate conferences only. Leadership is essential in environmental negotiations to solve collective action problems. Nonetheless, we also need to understand the role of non-leaders, as they are the ones who usually hinder progress in global environmental politics. Charles Parker et al. (Citation2015) have criticised the literature’s strong focus on leaders and addressed this shortcoming by studying the perception by followers. Here we take this approach a step further and study how delegates to international negotiations perceive different kinds of actors.

From a different perspective, an increasing number of scholars studying the EU as an international actor argue that understanding perceptions is necessary because it impacts the EU’s success as an international player (Lucarelli and Fioramonti Citation2010). Relying on interviews with EU and non-EU delegates who attended the climate conference in 2008, Bertil Kilian and Ole Elgström (Citation2010) find that all perceived the EU as a key player. Similarly, when analysing the EU’s perceived role in the United Nations Forum on Forests as well as in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species in 2004, Ole Elgström (Citation2007) shows that the EU is perceived as an influential player that often focuses on internal coordination and is faced with internal controversies. These studies provide interesting insights into the perceived role of the EU. However, focusing solely on the EU makes it challenging to compare its role with that of other global actors. While we study the perceived roles of all major countries and regional groups, our typology is intended to be applicable to other actors in global environmental negotiations too.

A typology of roles in international environmental negotiations

As mentioned, we conceptualise the perceived roles of countries and regional groups based on three dimensions: ambition, diplomatic activity and influence. Ambition is the extent to which a country or regional group prefers a negotiation outcome that will lead to a high level of environmental protection. The country or regional group is considered ambitious if it is among those actors that prefer the most stringent environmental policy outcomes (Burns et al. Citation2020). Diplomatic activities are the actions employed by a country or regional group to promote its positions in international environmental negotiations and to reach out to third countries. Influence is the extent to which the country or regional group has an impact on the outcome of international negotiations. Briefly, ambition refers to what the country or regional group wants, activity to what it does and influence to what it achieves. A low level of ambition, activity or influence means being among the least ambitious, least active or least influential countries and regional groups in the negotiations. Conversely, a high level of ambition, activity or influence refers to the country or regional group being among the most ambitious, active or influential countries and regional groups.

Based on these three role dimensions, we distinguish between eight ideal types of perceived roles of countries and regional groups in international environmental negotiations (). Each ideal type is a combination of different levels (low/high) of ambition, diplomatic activity and influence.

A reformist leader has a highly ambitious position, a high level of diplomatic activity and a high level of influence on the negotiation outcome. The reformist leader is similar to what is usually meant in the literature by leader, that is, an actor who is influential and able to mobilise followers (Nye Citation2008; Underdal Citation1994). Moreover, leadership is often associated with a ‘leading-by-example’ approach (Schunz Citation2019), whereby countries and regional groups demonstrate domestically that more ambitious policies are achievable. Therefore, leaders are commonly understood as being ambitious, active and influential in international negotiations.

A conservative leader puts forward a position with a low level of ambition, is highly active in the negotiations and achieves a high level of influence. Following the argument that a leader does not necessarily push for ambitious goals of collective benefit (Parker and Karlsson Citation2014), ‘leader’ is also used as the label for this second ideal type.

A lucky reformist bystander enters the negotiations with a high level of ambition, but abstains from most diplomatic activity. Nonetheless, the lucky reformist bystander is influential, but that is rather ‘by chance’ – which is, admittedly, quite unlikely (see further).

An influential blocker has a low level of ambition and shows a low level of engagement in diplomatic activity. Nonetheless, the influential blocker achieves a high level of influence – which is not impossible but rather implausible.

A failing pusher prefers a highly ambitious outcome of the international negotiations and is highly active in pursuing that objective. However, these activities do not pay off as the ambitious preferences are not reflected in the outcome, and the influence of the failing pusher is low.

A failing conservative actor puts forward a position with a low level of ambition and engages in diplomatic activity during international negotiations. However, despite being active and preferring an outcome close to the status quo, a failing conservative actor does not succeed in influencing the outcome of the negotiations.

A reformist bystander enters the negotiations with a highly ambitious position. However, it engages little in diplomatic activity and has a low level of influence.

A conservative bystander has a low level of ambition, engages little in diplomatic activity and has little influence. The conservative bystander does not want to change the status quo, is not active and is not successful in influencing the negotiation outcome.

Table 1. Ideal types of roles

These eight ideal types are theoretical constructs. The typology captures the variety of roles countries and regional groups can have in international environmental negotiations, based on the assumption that an actor can be perceived as having either high or low values on the three role dimensions. We apply this typology to the perceptions of different countries and regional groups to examine which ideal types can be observed empirically. Testing our typology against empirical material will reveal if the theoretically constructed ideal types also exist in practice. Whereas some ideal types seem less likely to occur in reality (for example, the lucky reformist bystander and the influential blocker), we do not exclude a priori that a country or regional group can be perceived as playing that role in international environmental negotiations. In the conclusion, we will reflect on how plausible the occurrence of the different ideal types is.

Data and methodology

To assess the perceived roles of countries and regional groups, we conducted an online survey with country delegates who attended the 2019 BRS COPs, the 2018 CBD COP and the 2019 UNEA meeting. These negotiations took place in the same period (2018-2019) in United Nations-wide forums dealing with environmental matters and characterised by quasi-universal membership, high levels of institutionalisation and a lower level of politicisation than climate negotiations. To identify the delegates to the specific meetings, we relied on the lists of participants published by the forums’ secretariats and contacted every delegate with a valid e-mail address. In total, 659 out of 3144 invited delegates responded to our survey, which represents a response rate of 21 per cent. The survey was completed by 222 delegates to the BRS Conventions (that is, a response rate of 25.9 per cent), 332 delegates to CBD (response rate of 22.3 per cent) and 105 delegates to UNEA (response rate of 13.1 per cent). The relatively low response rate is rather common in studies of elite populations, as they usually have less time to participate (Walgrave and Joly Citation2018).

The survey included participants (civil servants, heads of delegation, diplomats, ministers) from all five electoral groups of the UN. We selected countries and groups that are considered the major actors in international environmental negotiations. Our assessment is based on exploratory interviews, secondary literature as well as reports of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin. The selection was also designed to ensure broad geographical coverage. The selected countries are Brazil, Canada, China, the EU, India, Japan, Norway, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Switzerland and the US. The US was only included in the UNEA survey, because the US has only an observer status in the BRS Conventions and CBD. In addition, we included the EU in a comparison between individual countries, because the EU’s status in these forums largely resembles the status of the other selected countries. Unlike all other regional groups, the EU is a party to the BRS Conventions and CBD. Even though the EU is only an observer in UNEA, it normally negotiates as a single actor within that forum too. Hence, we consider the EU as a single negotiator in all three forums and thus included it in both the analysis of countries and the analysis of groups. Consequently, we did not consider any EU member state separately in the comparison between countries. As far as groups are concerned, we selected electoral groups, regional organisations and political groups, as they all play a major role in environmental negotiations. Those are the African Group, the Asia-Pacific Group, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the EU, the G77, the Latin American and Caribbean Group (GRULAC), JUSCANZ,Footnote2 the Like-Minded Megadiverse Countries (LMMC) and the Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

The survey was structured into three parts, focusing respectively on the ambition, diplomatic activity and influence of different countries and regional groups. At the beginning of each section, we provided a definition of ambition, activity and influence in order to ensure that all survey participants had the same understanding of these concepts. In the survey, we asked delegates to rate the general level of ambition/activity/influence of the different countries and regional groups. Delegates compared countries with other countries, and regional groups with other regional groups.Footnote3 The responses to all survey questions were based on a Likert Scale from 1 to 5, where 1 stands for ‘is among the least ambitious/active/influential countries/groups’; 2 for ‘is less ambitious/active/influential than the average countries/groups’; 3 for ‘is among the average ambitious/active/influential countries/groups’; 4 for ‘is more ambitious/active/influential than the average countries/groups’; and 5 for ‘is among the most ambitious/active/influential countries/groups’. All questions included a ‘don’t know/not applicable’ option in the event that survey participants could or would not like to rate a country or regional group. In addition, we gave them the opportunity to explain their ratings in open-ended questions after each section.

As we defined the scale points of the Likert Scale, we cannot assume that they are all at the same distance. Consequently, we are not able to calculate an average score per actor. Moreover, we had to dichotomise our results, since our typology of roles is based on dichotomous (low/high) variables. To construct the ideal types for the countries and regional groups, we first classified each score as either ‘low’ or ‘high’, where 1, 2 and 3 stand for ‘low’ and 4 and 5 stand for ‘high’.Footnote4 Recoding the results into dichotomous variables allowed us to identify, for each participant, the ideal type they attributed to each country and regional group. Only fully complete surveys for all three dimensions – that is, without ‘don’t know/not applicable’ responses – were included in our analysis.

Role perceptions of countries and regional groups

This section discusses how delegates perceive the roles of countries and regional groups in international environmental negotiations. The combined results on the role of countries and the role of groups show that the most commonly observed ideal types are the reformist leader and the conservative bystander (). Overall, 43 per cent of all survey participants identified countries and regional groups as reformist leaders, meaning they attributed them a high score for all three role dimensions. Twenty-eight per cent of survey participants assessed countries and regional groups as conservative bystanders, with a low level of ambition, activity and influence. With 9 per cent of responses, the conservative leader is the third most common ideal type.

Table 2. Total frequency of ideal types

Each of the five remaining ideal types is identified in only 5 per cent or less of the responses. As mentioned above, from a theoretical point of view, the occurrence of two ideal types – the lucky reformist bystander and the influential blocker – is less likely. The combination of not being active in the negotiations, but still being influential is indeed rather implausible. Despite the theoretical implausibility of the occurrence of these ideal types, some countries and regional groups are perceived as playing that role, which indeed shows that they could not be excluded a priori from our list of ideal types. Yet, the mechanism behind this combination remains unclear. Furthermore, the ideal types of the failing pusher, failing conservative actor and reformist bystander are theoretically more logical, but they also occur rarely. This is most likely due to our selection of countries and regional groups. Our sample includes rather large, powerful countries, which are – just like regional groups – generally less likely to be inactive and uninfluential in the negotiations.

We did not find significant differences based on the origin of survey participants. In contrast to Charles Parker and Christer Karlsson (Citation2018), who found that countries and regional groups are more often recognised as leaders by negotiators from the country or regional group they belong to, we do not find this pattern in our data (Delreux and Ohler Citation2021). In other words, our data do not show a pattern in which countries or regional groups are assessed as more ambitious, active or influential by delegates from that region than by delegates from other regions of the world.Footnote5

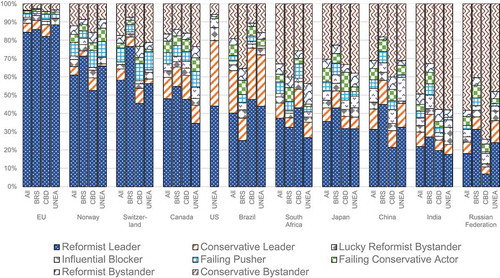

Role perceptions of countries in international environmental negotiations

Our results on role perceptions of countries show that the EU, Norway and Switzerland are the most recognised reformist leaders in international environmental negotiations (). For all forums combined, over 50 per cent of survey participants identify these actors as reformist leaders. The EU especially stands out, as over 80 per cent of participants consistently describe it as a reformist leader. Canada, the US and Brazil are also – albeit to a lower extent (over 40 per cent) – often described as reformist leaders. South Africa, Japan and China are perceived as reformist leaders by about one third of participants. By contrast, India and the Russian Federation are recognised as reformist leaders by only about 20 per cent of participants.

The Russian Federation and India are mostly perceived as conservative bystanders. About 50 per cent of survey participants describe the Russian Federation and India as such. Moreover, about one third of participants perceive China, Japan and South Africa as conservative bystanders. Those countries are thus perceived either as reformist leaders or as conservative bystanders. Less than 20 per cent see Brazil, Canada, Norway and Switzerland as conservative bystanders.

Several countries are perceived as conservative leaders, who favour unambitious positions and are active and influential. The strongest conservative leader is the US, with 36 per cent of participants describing it as such. Twenty-three per cent of respondents consider Brazil to be a conservative leader. In addition, Canada and China are perceived as conservative leaders by slightly over 10 per cent of participants. The other ideal types are only observed very rarely.

Even though the results for many countries are rather similar for the three environmental forums (BRS, CBD and UNEA), we observe some differences between the role perceptions in different forums (). In the BRS Conventions, the EU, Norway, Switzerland and Canada are perceived as reformist leaders by over 50 per cent of participants. China and Japan, too, are seen as reformist leaders, by approximately 45 per cent of respondents. On the contrary, the Russian Federation and South Africa are described as conservative bystanders (40 per cent). Finally, Brazil and India are difficult to attribute to one ideal type in the BRS Conventions. Whereas one third of participants identify them as conservative bystanders, one quarter assess them as reformist leaders, and still over 10 per cent consider them as conservative leaders.

In CBD, the EU and Norway are the strongest reformist leaders, being recognised as such by over 50 per cent of survey participants. In addition, Brazil, Canada, South Africa and Switzerland are seen as reformist leaders by more than 40 per cent of respondents. An additional 28 per cent of respondents identify Brazil as a conservative leader. The Russian Federation and India are perceived as conservative bystanders in CBD by the majority of respondents. Moreover, 40 per cent see China as a conservative bystander: hence, contrary to the BRS Conventions, China is more often identified as a conservative bystander than as a reformist leader in the CBD context. The results for Japan are intriguing, as there is a strong division among survey participants. One third see Japan as a reformist leader, another third as a conservative bystander and 10 per cent as a failing conservative actor.

In UNEA, the EU, Norway and Switzerland are recognised as reformist leaders by over 50 per cent of respondents. In addition, while Brazil and the US are clearly seen as leaders, delegates are split on their level of ambition. In both cases, 44 per cent of participants perceive them as reformist leaders, but another 28 per cent regard Brazil as a conservative leader, and 36 per cent see the US as a conservative leader. Canada is mostly seen as a reformist leader, although only by 35 per cent. In UNEA, according to 58 per cent of respondents, India is the strongest conservative bystander. Moreover, the Russian Federation and South Africa are described as such by over 40 per cent of participants. Survey participants are instead divided over China and Japan: whereas one third identify the two countries as reformist leaders, another third see them as conservative bystanders. Moreover, 13 per cent perceive China to be a conservative leader or an influential blocker.

Our results show that international environmental negotiations are not characterised by a single country playing the role of leader. Rather, multiple actors are perceived as leading, at least to some extent. However, in all forums, the EU consistently stands out as the most prominent reformist leader. Survey participants argue that the EU is typically well prepared and has more resources, making it easier for the Union to be active and influential. Others claim that the EU constantly tries to gain support from both developed and developing countries. Along with the EU, Norway, Switzerland and Canada are important reformist leaders. In UNEA, the US and Brazil are also leaders, but survey participants are divided over whether they advocate for ambitious or unambitious outcomes, and therefore describe them as either reformist or conservative leaders.

Whereas some actors show similar results in all three environmental forums, we identify critical differences for others. Brazil is not perceived as having a leading role in the BRS Conventions but is seen as being among the most active and influential countries in CBD and UNEA. Japan and China are both reformist leaders in the BRS Conventions, but do not perform leading roles in the other forums. In addition, South Africa is rather a conservative bystander in the BRS Conventions and UNEA, though it is a reformist leader in CBD.

Furthermore, our results do not show one clear ideal type per forum for all countries. In fact, for several countries, there is no clear ideal type for some of the forums, as their role is not perceived in the same way by all respondents. For example, our results do not provide a clear picture of the role of the Russian Federation and India in the BRS Conventions. This might be related to the different issues negotiated at the BRS COPs in 2019. While both countries were rather inactive in the negotiation of a new agreement on the management of plastic waste, they opposed the listing of chrysotile asbestos in the annex to the Rotterdam Convention (Templeton et al. Citation2019). Our tentative explanation for these diverging results is that survey respondents attributed very different roles to these countries, depending on the issues that each respondent was involved in during the negotiations.

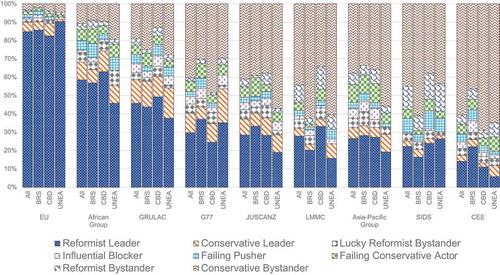

Role perceptions of regional groups in international environmental negotiations

The results on how survey participants perceive the role of regional groups show that also among the latter, the EU stands out as the actor who is most frequently recognised as a reformist leader (85 per cent). No other regional group comes close to this level. However, the African Group scores high as well, as 59 per cent of survey participants describe it as a reformist leader. Whereas 46 per cent of respondents identify GRULAC as a reformist leader, only between 22 and 30 per cent consider that the G77, JUSCANZ, LMMC, the Asia-Pacific Group and the SIDS are reformist leaders. CEE has the lowest level of recognition as reformist leader, as only 14 per cent perceive it as such.

Most regional groups are strongly perceived as conservative bystanders. Sixty-one per cent of respondents describe CEE as such, while approximately 40 per cent include the Asia-Pacific Group, G77, JUSCANZ, LMMC and SIDS in this ideal type. The results for the African Group and GRULAC are considerably lower, but nonetheless over 10 per cent of respondents describe them as conservative bystanders.

Many ideal types occur only to a small extent. The African Group, GRULAC and the G77 are recognised as conservative leaders by over 10 per cent of participants. On the contrary, the LMMC and SIDS are described as reformist bystanders by over 10 per cent of respondents. In addition, 10 per cent describe the Asia-Pacific Group as a failing conservative actor. The remaining ideal types, that is, the lucky reformist bystander, influential blocker and failing pusher, are only rarely perceived.

Similar to what we observed for countries, the role of regional groups is relatively similar in the three forums, but there are also notable differences (). In the BRS Conventions, the EU and the African Group are the strongest reformist leaders, with recognition levels of 55 per cent or higher. Moreover, also GRULAC is highly recognised in that ideal type, as 44 per cent of survey participants describe it as such. Several other regional groups are instead perceived as conservative bystanders. More than 60 per cent describe the LMMC and the SIDS as such. In addition, 46 per cent see CEE as a conservative bystander. Results for the Asia-Pacific Group, G77 and JUSCANZ are mixed. Whereas one third of delegates perceive them as reformist leaders, another third identify them as conservative bystanders. In addition, a further 10 per cent consider that the Asia-Pacific Group and JUSCANZ are failing conservative actors.

In the context of CBD, the EU and the African Group are described as reformist leaders by over 60 per cent of delegates. In addition, GRULAC is a strong reformist leader, with 49 per cent of respondents identifying it as such. The strongest conservative bystanders are CEE (69 per cent) and the G77 (49 per cent). For the Asia-Pacific Group, JUSCANZ, LMMC and the SIDS, results are rather mixed. However, participants identify them more as conservative bystanders than as reformist leaders. In addition, the Asia-Pacific Group is described as a failing conservative actor (11 per cent), the SIDS as a failing pusher (10 per cent) and the LMMC (12 per cent) as well as the SIDS (14 per cent) as reformist bystanders.

In UNEA, the EU scores the highest as a reformist leader, with a considerable advantage over all other regional groups: whereas the EU is perceived to be a reformist leader by 90 per cent of survey participants, the second strongest reformist leader is the African Group, at 46 per cent. In the context of UNEA, many regional groups are clearly described as conservative bystanders. Over 55 per cent of respondents perceive the Asia-Pacific Group, CEE, JUSCANZ and LMMC as conservative bystanders. The SIDS are identified as conservative bystanders by 43 per cent of delegates. The results for G77 and GRULAC are less straightforward. Over 35 per cent of respondents consider them as reformist leaders. However, nearly 30 per cent believe that they are conservative bystanders, and over 16 per cent describe them as conservative leaders.

On the whole, these results clearly indicate that, among the regional groups, the EU is the strongest reformist leader in all environmental forums. The African Group also is an important reformist leader. Both regional groups meet regularly and coordinate their positions and actions, and they are the groups that put forward a common position most frequently. This is also reflected in the results, as we asked survey participants to choose ‘don’t know/not applicable’, if they assessed that a regional group does not act as a group. This option is chosen to a considerably lesser extent for the EU and the African Group than for the other groups. Moreover, some survey participants argued in the open survey questions that only the EU, the African Group and, to some extent, GRULAC are actually acting as a group in negotiations. Across the three forums, CEE is clearly the best example of a conservative bystander. This can be explained by the high number of countries being a member of both CEE and the EU. As the EU normally has a common position and is actively engaging in negotiations, CEE is rarely of relevance to EU member states, thereby considerably reducing its overall importance. One survey participant from BRS responded to an open survey question that CEE only meets to discuss candidates for the elections to the BRS bodies.

The Asia-Pacific Group, JUSCANZ, the LMMC and the SIDS are perceived as conservative bystanders, because they rarely represent a common position. Rather, member countries act individually in the negotiations. In addition, the SIDS face the challenge of including countries with very small delegations, making it difficult for the group to be active and influential. For GRULAC and the LMMC, this is less a problem, although they include countries with opposing views, as one CBD participant claims. The Asia-Pacific Group is faced with sheer diversity of culture and interests, which makes it difficult for it to have a common position on any matter. The drastic differences between the EU and the other regional groups can, to some extent, be explained by the differences in their legal status, especially in the BRS Conventions and CBD, to which the EU is a party. The results for those regional groups that do not regularly represent a common position should be interpreted with some caution, as many survey participants chose the ‘don’t know/not applicable’ option for those groups, thereby considerably reducing the number of responses used to assess their role perception. It may also explain the difficulties encountered in attributing an ideal type to some of these groups.

Conclusion

By applying our role typology to the perceptions of various countries and regional groups, we can highlight their typical roles in international environmental negotiations. Highly ambitious actors are often active in negotiations and able to influence their outcome: they are reformist leaders. Conversely, actors with a low level of ambition are mostly less active and less influential in international negotiations: these are conservative bystanders. Other countries are conservative leaders, as they favour rather unambitious outcomes, but are highly active and influential. The ideal type of conservative leader allows for distinguishing the role played by countries such as Brazil and the US from more reformist leaders such as the EU or Norway. Our typology therefore makes it possible to identify different types of leaders, proposing an alternative to the traditional differentiation between structural, directional and instrumental leaders (Gupta and Ringius Citation2001). In addition, our typology encompasses a vast portion of non-leaders, such as the Russian Federation or India, which are perceived to be conservative bystanders. Testing our typology showed that the other proposed ideal types are less common. However, this might have been different had smaller countries been included in the analysis, calling for future research.

We also find that the role of many countries and regional groups is perceived in a rather consistent manner in the three forums. We can therefore assume that those actors will occupy similar roles in other environmental negotiations. This is especially accurate for those actors with the most consistent results, like the EU, Norway and most regional groups. Overall, the EU is the most prominent reformist leader, followed by Norway, Switzerland, Canada and the US. The US is clearly a leader, although participants are divided on its level of ambition (and thus on whether it is a reformist or a conservative leader). For other countries, such as China, Japan and South Africa, role perceptions are more diverse, making it difficult to draw clear conclusions on their roles. Our tentative explanation is that these countries are perceived differently depending on the issue under negotiation. Whereas we have provided only a few examples in this article, further research could look more closely into some key issues, trying to examine how the level of ambition, activity and influence of each country in a specific forum varies depending on the issue under discussion.

For regional groups, results are more straightforward. The EU, the African Group and GRULAC are reformist leaders; all other regional groups are instead conservative bystanders in international environmental negotiations. This is mostly explained by the fact that those groups do not consistently coordinate a common position, and their member countries rather rely on ad-hoc coalitions. Many regional groups align their position only on very specific items that are critical to the region.

To conclude, this article contributes to the literature on leadership and roles in international environmental negotiations by studying a large set of countries and regional groups. It highlights that role perceptions in forums such as the BRS Conventions, CBD and UNEA differ from those in climate change negotiations. In fact, whereas Charles Parker and Christer Karlsson (Citation2018) argued that in climate negotiations, China is more often perceived as a leader than the EU, our results on non-climate regimes show that the EU is most often recognised as leader and that China has rather mixed results. Our analysis contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the roles that countries and regional groups are perceived to play in international environmental negotiations. However, our descriptive survey data do not allow us to identify the reasons that underlie those findings. Further research would therefore benefit from more qualitative data and a focus on specific countries or regional groups to explain the reasons for their role perceptions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Marine Bardou for her research assistance. The authors acknowledge the UACES Research Network ‘The Role of Europe in Global Challenges: Climate Change and Sustainable Development’ for the organisation of a dedicated online workshop, and the co-editors for bringing this Special Issue to fruition. The Jean Monnet Network ‘Governing the EU’s climate and energy transition in turbulent times’ (GOVTRAN: www.govtran.eu), which is funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union, deserves credit for additional support. The authors would also like to thank colleagues from ISPOLE (UCLouvain), participants of the 2020 UACES Virtual Conference and three anonymous referees for their valuable input and comments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Frauke Ohler

Frauke Ohler is a PhD candidate at the Institut de sciences politiques Louvain-Europe (ISPOLE), University of Louvain (UCLouvain), and the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS), Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium.

Tom Delreux

Tom Delreux is Professor of EU politics at the Institut de sciences politiques Louvain-Europe (ISPOLE), University of Louvain (UCLouvain), Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. Email: [email protected]; Twitter: @tomdelreux

Notes

1 The BASIC Group is made up of Brazil, South Africa, China and India.

2 The name of the group is the acronym of the founding members: Japan, the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

3 For regional groups, we asked participants to rank them according to their ambition, activity and influence as a regional group and not to consider member countries individually. If the delegates felt that a regional group does not engage in the negotiations as a group, they should select the option ‘don’t know/not applicable’.

4 A score of 3, which means being among the average countries/groups, is less evidently attributable to ‘high’ or ‘low’. However, based on the survey results as well as previous interview experience, we can well argue that a score of 3 refers to a low level of ambition, diplomatic activity and influence. In fact, we observed a bias towards the more positive results on all questions, in the sense that a score of 4 or 5 was selected in 65.5 per cent of responses, whereas a score of 1 was selected in 2.9 per cent and a score of 2 in 8.8 per cent of responses. Moreover, as negotiations are usually consensus-based, some delegates claimed that all actors are active and influential to some extent. Consequently, respondents were reluctant to attribute a score of 1 or 2. For these reasons, we evaluate a score of ‘3’ as ‘low’.

5 We operationalised the geographical affiliation of participants by referring to the UN electoral groups to which their country belongs.

References

- Andresen, Steinar, and Agrawala, Shardul. 2002. Leaders, Pushers and Laggards in the Making of the Climate Regime. Global Environmental Change 12 (1): 41–51.

- Bäckstrand, Karin, and Elgström, Ole. 2013. The EU’s Role in Climate Change Negotiations: From Leader to ‘Leadiator’. Journal of European Public Policy 20 (10): 1369–86.

- Burns, Charlotte, Eckersley, Peter, and Tobin, Paul. 2020. EU Environmental Policy in Times of Crisis. Journal of European Public Policy 27 (1): 1–19.

- Delreux, Tom, and Ohler, Frauke. 2021. Ego versus Alter: Internal and External Perceptions of the EU’s Role in Global Environmental Negotiations. Journal of Common Market Studies. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13182.

- Elgström, Ole. 2007. The European Union as a Leader in International Multilateral Negotiations: A Problematic Aspiration? International Relations 21 (4): 445–58.

- Elgström, Ole, and Smith, Michael, eds. 2006. The European Union’s Roles in International Politics: Concepts and Analysis. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gupta, Joyeeta, and Ringius, Lasse. 2001. The EU’s Climate Leadership: Reconciling Ambition and Reality. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 1 (2): 281–99.

- Gurol, Julia, and Starkmann, Anna. 2020. New Partners for the Planet? The European Union and China in International Climate Governance from a Role‐Theoretical Perspective. Journal of Common Market Studies. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13098.

- Harnisch, Sebastian. 2011. Role Theory: Operationalization of Key Concepts. In Sebastian Harnisch, Cornelia Frank, and Hanns W. Maull, eds. Role Theory in International Relations: Approaches and Analyses: 7–15. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Holsti, K. J. 1970. National Role Conceptions in the Study of Foreign Policy. International Studies Quarterly 14 (3): 233–309.

- Kilian, Bertil, and Elgström, Ole. 2010. Still a Green Leader? The European Union’s Role in International Climate Negotiations. Cooperation and Conflict 45 (3): 255–73.

- Liefferink, Duncan, and Wurzel, Rüdiger K. 2017. Environmental Leaders and Pioneers: Agents of Change? Journal of European Public Policy 24 (7): 951–68.

- Lucarelli, Sonia. 2014. Seen from the Outside: The State of the Art on the External Image of the EU. Journal of European Integration 36 (1): 1–16.

- Lucarelli, Sonia, and Fioramonti, Lorenzo. 2010. External Perceptions of the European Union as a Global Actor. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nye, Joseph. 2008. The Powers to Lead. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oberthür, Sebastian, and Groen, Lisanne. 2017. The European Union and the Paris Agreement: Leader, Mediator, or Bystander? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 8 (1): e445.

- Parker, Charles F., and Karlsson, Christer. 2014. Leadership and International Cooperation. In R. A. W. Rhodes and Paul t’Hart, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Political Leadership: 580–94. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Parker, Charles F., and Karlsson, Christer. 2018. The UN Climate Change Negotiations and the Role of the United States: Assessing American Leadership from Copenhagen to Paris. Environmental Politics 27 (3): 519–40.

- Parker, Charles F., Karlsson, Christer, and Hjerpe, Mattias. 2015. Climate Change Leaders and Followers: Leadership Recognition and Selection in the UNFCCC Negotiations. International Relations 29 (4): 434–54.

- Parker, Charles F., Karlsson, Christer, and Hjerpe, Mattias. 2017. Assessing the European Union’s Global Climate Change Leadership: From Copenhagen to the Paris Agreement. Journal of European Integration 39 (2): 239–52.

- Parker, Charles F., Karlsson, Christer, Hjerpe, Mattias, and Linnér, Björn-Ola. 2012. Fragmented Climate Change Leadership: Making Sense of the Ambiguous Outcome of COP-15. Environmental Politics 21 (2): 268–86.

- Schunz, Simon. 2019. The European Union’s Environmental Foreign Policy: From Planning to a Strategy? International Politics 56: 339–58.

- Templeton, Jessica, et al. 2019. Summary of the Meetings of the Conferences of the Parties to the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions: 29 April – 10 May 2019. Earth Negotiations Bulletin, International Institute for Sustainable Development 15 (269).

- Torney, Diarmuid, Biedenkopf, Katja, and Adelle, Camilla. 2018. Introduction: European Union External Environmental Policy. In Camilla Adelle, Katja Biedenkopf and Diarmuid Torney, eds. European Union External Environmental Policy: Rules, Regulation and Governance beyond Borders: 1–15. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Underdal, Arild. 1994. Leadership Theory: Rediscovering the Arts of Management. In I. William Zartman, ed. International Multilateral Negotiation: Approaches to the Management of Complexity: 178–97. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Joly, Jeroen K. 2018. Surveying Individual Political Elites: A Comparative Three-country Study. Quality & Quantity 52 (5): 2221–37.

- Wurzel, Rüdiger K., Liefferink, Duncan, and Torney, Diarmuid. 2019. Pioneers, Leaders and Followers in Multilevel and Polycentric Climate Governance. Environmental Politics 28 (1): 1–21.

- Young, Oran R. 1991. Political Leadership and Regime Formation: On the Development of Institutions in International Society. Journal of International Organization 45 (3): 281–308.