ABSTRACT

Regional organisations in Africa have not managed to form coherent coalitions while negotiating about Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with the European Union (EU). Either the membership of EPA groups is not congruent with the membership of existing regional organisations, or crucial member states refuse to sign the EPAs and put their regions’ unity at risk. We argue that these problems are due to the differentiated trade rules of the EU, which privilege some trade partners and some commodity exports over others. Large African countries, which enjoy privileged access to the European market, do not have incentives to implement the unpopular EPAs, which are based on reciprocal trade liberalisation. As a result, they obstruct the negotiation process or refuse to implement the EPAs. This mechanism is illustrated at the examples of the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

1. Introduction

Regional economic communities (RECs) in Africa have not been able to build up stable regional negotiation groups when bargaining with the European Union (EU) about Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs). Most notably, the member states of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) are split in four different EPA groups, which makes it impossible to proceed with regional integration and to establish a customs union (SADC-CU) on top of the current free trade area (SADC-FTA) (Muntschick Citation2017; Murray-Evans Citation2015; Stevens Citation2006, Citation2008). Other African EPA-groups also face difficulties in keeping their unity when negotiating with the EU. The East African Community (EAC) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) EPA-groups are congruent with the membership of the respective regional organizations, but single member states refuse to implement the agreed EPAs in both regions. In this way, Tanzania blocks the realization of the EAC-EPA, whereas Nigeria does the same with the ECOWAS-EPA. This disunity of the African RECs is a puzzle because the African countries could have strengthened their own bargaining position within the EPA negotiations when acting as a regional block (World Bank Citation2000, 17–21). In this way, they could have achieved more favourable trade agreements with the EU, and they could have strengthened their regional ties at the same time. However, instead of pushing regionalism in Africa, the EPA negotiations have highlighted the structural difficulties of regionalism in developing regions of the global south. This runs counter to the EU’s expressed goal to actively support regionalism in other world regions and to establish interregional relations with these regions (Buzdugan Citation2013; Haastrup Citation2013; Draper Citation2007; Elgström and Pilegaard Citation2008).

The EPAs are built upon the principle of reciprocal trade liberalisation in which course not only the EU, but also African countries open up their domestic markets for imports. Before the turn of the millennium, the Lomé convention had granted former colonies in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific (the so-called ACP-countries) unconditional access to the European market. However, during the late 1990s, the World Trade Organization (WTO) ruled that the Lomé convention was in conflict with global trade rules, because it discriminated against other developing countries in Asia and Latin America (Forwood Citation2001). To avoid further conflict with WTO rules, the Cotonou agreement of 2000 laid down that the EPAs shall establish full-fledged trade agreements between groups of African countries and the EU. Accordingly, at least 85% of all trade between the participating countries shall be tariff-free. This opening up of African markets has been heavily criticised by African countries, development agencies and academics alike (Borrmann, Busse, and de la Rocha Citation2007; Farrell Citation2005; Hallaert Citation2010; Hurt Citation2012; Langan and Price Citation2015; Slocum-Bradley and Bradley Citation2010). It endangers especially the rudimentary manufacturing sector of African countries, which is not competitive on a global scale and needs a high level of protection (Claar and Nölke Citation2013; Ilorah and Ngwakwe Citation2015). The EPAs allow for some limited exceptions from trade liberalisation and provide flanking development aid in order to reduce the negative effects of market liberalisation, but nevertheless the African countries need to lower their trade barriers considerably when implementing EPAs.

Access to the European market is extremely important for African economies, but not all African countries need to implement EPAs and open up their domestic markets in order to get this access. The EU’s external trade policy differentiates between trade partners with different economic potentials and different trade patterns (Woolcock Citation2014). This means that African countries face very different trade regimes when exporting to the EU: least developed countries (LDCs) enjoy free access to the European market under the Everything-but-Arms (EBA) initiative, oil exports from some ACP-countries do not face any barriers when entering the European market, and the Trade Development and Cooperation Agreement (TDCA) granted South Africa access to the European market until recently. These different trade regimes constitute extra-regional economic privileges for the respective African countries (Krapohl Citation2017; Krapohl, Meißner, and Muntschick Citation2014). The privileged African countries only need to implement EPAs, if they have a genuine interest in regional integration in order to secure access to regional markets within Africa. Whether neighbouring markets are important enough for them to implement EPAs depends very much on the size of the respective economies. Intraregional trade is only important for smaller economies in Africa, if they get access to the large markets of regional powers. In contrast, the exports of large regional powers cannot be absorbed by smaller economies within their own region, but they are exported to other world regions (Fink Citation2017; Krapohl and Fink Citation2013; Muntschick Citation2017). As a result, small African countries may even implement EPAs if they already enjoy privileged access to the European market, but large African countries, which enjoy the same privileges, may become obstructers of EPA negotiations with the EU. Thus, the size of the economy, the value of intra- and extra-regional trade, together with the privileged status in extra-regional markets determine the interest of African states in negotiating EPAs.

The article proceeds by developing the theoretical argument in section two. Here, it is argued that developing regions may profit considerably from regional integration, if this helps them to improve their standing in relation to extra-regional economic partners. However, these common gains may be exceeded by individual losses for some member states if they have to give up extra-regional economic privileges. Thereafter, section three analyses the EPA negotiations of EAC, ECOWAS and SADC, which are arguably the most developed RECs on the African continent. It is demonstrated that each of the three regions includes at least one privileged member state, and that this has caused problems for the adoption and implementation of uniform EPAs. The conclusion summarizes the empirical findings and discusses the consequences for the EU’s trade and development policies.

2. The extra-regional logic of regionalism in the global south

Regionalism in the global south exists in the shadow of extra-regional economic dependence (Fawcett and Gandois Citation2010; Krapohl Citation2017). Intraregional trade is usually very low in African RECs, which depend economically on investments from, and exports to Europe (Krapohl and Fink Citation2013). Unlike in Europe, intraregional economic interdependence cannot be the main driver of regional integration in Africa. Nevertheless, even if intraregional economic interdependence is low, regionalism can improve the standing of African regions on the global market. Regional groups of countries have more economic and political weight than single countries on their own, and this should increase their bargaining power and actorness in interregional trade negotiations like the EPA negotiations with the EU (Doidge Citation2007; Mattheis and Wunderlich Citation2017; World Bank Citation2000). Thus, the extra-regional effects are a major rationale for African regionalism. However, the problem is that the extra-regional interests of African countries can also become a major obstacle for regional cooperation and stable economic integration within Africa.

2.1 Intra- and extra-regional benefits of regionalism

The economic structure of developing regions in Africa is fundamentally different from that of well-developed regions like the EU (Fink Citation2017; Krapohl and Fink Citation2013). Due to low levels of economic development and diversification, developing economies in the global south usually depend to a high degree on the export of few commodities, whereas manufactured goods are mostly imported. However, the main markets for commodities are well-developed economies of the global north, not developing economies in the regional neighbourhood. Thus, extra-regional trade is usually much more important for African RECs than intraregional trade. Nevertheless, considerable differences exist between large and small African countries. Due to the differences in market size, large African economies can still become important export destinations for the limited exports of small African economies. On the contrary, small African economies are unlikely to absorb the greater exports of their bigger neighbours. The result is a hub-and-spoke pattern of African trade relations (Fink Citation2017; Krapohl and Fink Citation2013; Muntschick Citation2017). Large African countries like Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa are the hubs of these trade networks, whereas their smaller neighbours constitute the spokes around them. Whereas extra-regional trade is more important for the large economies and for the region as a whole, intraregional trade may nevertheless be quite important for the smaller economies.

Even when the intraregional gains of regionalism in the global south are limited, developing regions can still profit from extra-regional gains of regional cooperation. Regionalism bears positive size and stability effects (Krapohl Citation2017), which can be utilised in interregional trade negotiations. RECs necessarily constitute larger markets than each of the member states on their own. Moreover, RECs are associated with improved political stability, because their members have other means to settle their disputes than resorting back to military force (Gartzke, Li, and Boehmer Citation2001; Haftel Citation2007). As a result, integrated regional markets become more attractive as trade partners, and regional groups can gain better leverage in interregional trade negotiations than each of their member states alone.

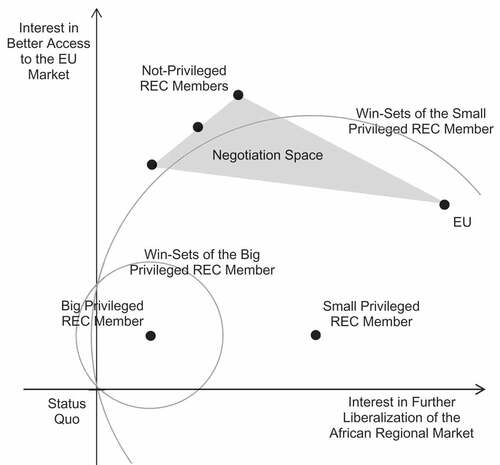

In , the three REC member states at the top of the graph can profit from forming a negotiation group. Any result of the negotiations will be located in the negotiation space between the three REC members and the EU. Together, the REC members can pull the final agreement more into the direction of EU market access and away from the liberalization of their own regional market than any of the three countries could do on their own. Thus, successful regional cooperation would be rewarded by better access to the EU market or by more protection of domestic markets or by both. This provides a motivation for regional cooperation in the global south which is very different to the motivation for regional market integration in well-developed regions like Europe. Whereas the economic gains of increasing intraregional trade are produced within well-developed regions themselves, the gains of improved extra-regional market access only emerge in the interaction with other world regions. As a result, regionalism in the global south is more sensitive to extra-regional influences than regionalism in the global north (Krapohl, Meißner, and Muntschick Citation2014).

2.2 Extra-regional economic privileges for single member states

The situation for REC negotiation groups changes fundamentally if one or more of their members already enjoy privileged access to the European market. The natures of such privileges are manifold (see section 2.3), but they all have in common that the respective REC members do not need to negotiate and implement EPAs in order to secure free access to their most important extra-regional export market. If the privileged trade relations with the EU do not require reciprocal trade liberalization, the privileged member state can avoid opening its own market by not implementing an EPA. Even if the privileged trade relations imply some degree of reciprocity, they nevertheless constitute a competitive advantage for the respective REC member in relation to its regional neighbours. Other regional economies may compete with the exports of the privileged member state on the European market, if they gain the same market access under an EPA. Thus, the privileged member state has an incentive to prevent its regional neighbours from enjoying the same beneficial trade rules as itself.

Whether a privileged REC member still has an interest in an EPA depends very much on its relative size within the region and its interest in intraregional trade liberalization. A small privileged member state may still profit from improved access to the bigger markets of its regional neighbours. In , the small privileged member state has some interest in the liberalization of the regional market, although it already has privileged access to the European market. As a result, its ideal position is relatively far away from the status quo, which implies that its win-set for interregional trade negotiations is relatively big and overlaps with the negotiation space between the not-privileged REC members and the EU (indicated by the large grey circle). Consequently, the interests of the small privileged member state can be accommodated within the REC negotiation group.

In contrast, a large privileged REC member is highly unlikely to profit a lot from intraregional trade with its smaller neighbours. The large REC member is dependent on extra-regional trade, and access to the EU market is already ensured by its privileges. As a result, the ideal position of a big privileged REC member is relatively close to the status quo. illustrates that this leads to a relatively small win-set of the privileged member state (indicated by the small grey circle), and the win-set does not overlap with the negotiation space between the not-privileged REC members and the EU. Consequently, it is very difficult to accommodate the interests of the big privileged member state within the REC negotiation group. The other REC members and the EU would need to agree on an EPA somewhere within the win-set of the privileged member state, but this would reduce their gains from interregional trade negotiations considerably. It is much more likely that the privileged REC member either obstructs the implementation of a common EPA, or that it directly leaves the negotiation group. Thus, the interregional negotiations are either stalled, or the EPA negotiation group is no longer consistent with REC membership.

2.3 Differentiation, trade profiles and bilateralism

There are several reasons why a particular country may enjoy privileged trade relations with the EU which are all based on the EU’s attempt to differentiate between trade partners with different economic potentials and different trade patterns. First, the EU’s trade rules distinguish between developing countries and LDCs (Woolcock Citation2014). Currently, 34 African LDCs enjoy free access to the European market under the EBA-initiative of the EU (Yu and Jensen Citation2005).Footnote1 In contrast to the old Lomé convention, the EBA-initiative conforms with WTO rules because it generally addresses LDCs and does not discriminate against nine LDCs from Asia, which do not belong to the ACP countries. Non-LDC developing countries in Africa fall back to the EU’s general scheme of preferences (GSP). Although the GSP still grants preferential market access to developing countries, it is nevertheless more restrictive than the EBA-initiative or the possible EPAs. Thus, non-LDC developing countries depend on successful EPA negotiations in order to get free access to the European market, whereas the LDCs are privileged and already enjoy this access. The LDCs may decide not to implement EPAs in order to avoid the negative effects of reciprocal trade liberalization for their domestic producers and the competition of more developed regional neighbours on the European market.

Second, some African states export commodities, which are so important for the EU that they do not face any import tariffs. Crude oil and natural gas are such raw materials, which are crucial for the energy needs of the European economies and do not face any customs when entering the EU.Footnote2 Thus, as long as such commodities are the main export products of a REC member, the respective country is privileged in its extra-regional trade relations, and it does not necessarily need to implement an EPA. Although such a privileged REC member does not need to fear the competition of its regional neighbours on the European market, it nevertheless can avoid reciprocal trade liberalization by leaving the EPA negotiation group or by refusing to implement the respective EPA.

Third, single African countries may also enjoy bilateral trade agreements with the EU. After the end of Apartheid, the EU was not willing to grant South Africa non-reciprocal free market access under the Lomé convention because the country was much more developed in economic terms than the other ACP-countries. In order to support the regime change in South Africa, the EU granted privileged access to its market under the TDCA in 1999 (Frennhoff Larsén Citation2007). Although the TDCA was less attractive than non-reciprocal free market access under the Lomé convention, it constituted privileged extra-regional trade relations between the EU and South Africa when the Lomé convention was abandoned and the EPA negotiation started (Muntschick Citation2017). Unlike the EBA-initiative, such a bilateral trade agreement does not allow the privileged REC member to avoid reciprocal trade liberalization, but it implies a competitive advantage for this member state on the European market. Thus, once again, the privileged member state faces an incentive to protect its privileged position and to impede the interregional negotiations.

3. EPA’s, privileges and African regionalism

To illustrate the negative effects of extra-regional privileges on the adoption and implementation of EPAs, we analyse the cases of EAC, ECOWAS and SADC. To date, none of these RECs have succeeded in the adoption and implementation of a common EPA that covers all member states. Although the SADC-minus EPA group has implemented an EPA, it only includes a minority of SADC members. EAC and ECOWAS have finalised EPA negotiations as complete negotiation groups, but they are still pending signatures from important member states. What all three cases have in common is that they include at least one member state that enjoys privileges in its extra-regional economic relations with the EU, and therefore has an incentive to obstruct the negotiation or implementation of uniform EPAs.

3.1 EAC

EAC is one of the oldest regional organizations in Africa. The ‘first’ EAC originates from 1967 and included Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, but it only lasted until 1977 due to irreconcilable political differences. The current EAC was founded in 1999 by the same member states, which were joined by Burundi and Rwanda in 2009 and by South Sudan in 2016.Footnote3 EAC has established a customs union and a common market, which makes it one of the most integrated RECs on the continent. It aims to form a monetary union by 2024 and ultimately a political federation.

EAC is mainly dependent on trade with extra-regional partners, and all EAC members trade more with countries outside of the region than with their regional neighbours (see ). The EU is one of the most important trade partners to the EAC member states. In 2017, 13.6% of EAC’s total trade was with the EU. This number is relatively low compared to other RECs in Africa, because of the large involvement of China (18.4% of total EAC trade) and India (11.4%) in East Africa. However, the EU is the leading destination for exports, as it received 17.8% of EAC’s total exports in 2017. Due to market size effects, the smaller regional economies (Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda) trade more within the region than with the EU. Therefore, they have a natural interest in regional integration, especially since they are also dependent on Kenya and Tanzania for access to the sea. The larger regional economies (Kenya and Tanzania) have different interests, as their exports mainly address the extra-regional market. Their motivation for regional cooperation is not so much intraregional trade, but the effects on interregional trade negotiations.

Table 1. EAC’s intra- and extra-regional trade in 2017.Footnote4

The EU does not treat all East African countries states equally, which leads to extra-regional privileges for some EAC member states. The East African LDCs Burundi, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda have free access to the European market. Kenya is the only EAC state that does not qualify as LDC and thus cannot fall back on the EBA-initiative. If EAC and the EU fail to agree on an EPA, Kenya falls under the standard GSP under which market access is considerably less favourable compared to an EAC-EPA. It is estimated that Kenya will face export duties around 100 million USD a year (European Parliament, 2018). However, with the Brexit coming closer, Kenya’s trade interest in the EU might decrease, as in 2017 more than a quarter (27%) of EU imports from Kenya went to the United Kingdom.

The EPA negotiations with the EU seemed to have a relatively positive impact on EAC’s unification for some time, as it forced Tanzania to ‘choose side’ and commit to either EAC or SADC (Tanzania is a member of both RECs). Initially, Tanzania negotiated an EPA together with the SADC-minus EPA group, but when EAC established a customs union in 2005 and a common market in 2010, it became essential for the regional member states to participate in one single EPA in order to harmonize their external trade regimes. Thus, Tanzania joined the EAC-EPA group in 2007, and the REC members were unified in one single negotiation group. The EAC-EPA negotiations were finalized in 2014, and the EU, Kenya and Rwanda signed the agreement in 2016. The EAC-EPA is still pending signatures from Burundi, Tanzania and Uganda.Footnote6 Therefore the EPA cannot yet be enacted because the EPA requires the signatures of all parties to be put into force.

Burundi and Uganda are relatively small EAC member states, and their share of intraregional trade is slightly bigger than their trade with the EU (see ). Thus, the two countries should have an interest in regional cooperation in order to profit from the intraregional gains of regional market liberalization. In addition, the smaller EAC member states are landlocked and exports need to pass through Kenya or Tanzania to access the sea. Thus, Uganda has expressed its intention to sign the EPA,Footnote7 but it seems to await a full consensus between the EAC member states. However, Burundi is under sanctions of the EU since 2016. The EU has cut financial support for the government of Burundi and initiated a travel ban and asset freeze against four Burundian persons as a response to the political and humanitarian crisis in Burundi.Footnote8 Burundi naturally has expressed its dissatisfaction with the EU measures and has proclaimed it will not sign the EPA due to its ‘deteriorating relations with Europe’.Footnote9 If relations between the EU and Burundi improve and these sanctions are lifted, Burundi is likely to sign the EAC-EPA. Thus, neither of the two smaller member states is opposing the EAC-EPA in principle, and either the EU or the other EAC member states could motivate them to sign the agreement.

The situation is different for Tanzania, which is the second largest economy of EAC. Tanzania has less of an interest in an EAC-EPA than Kenya because it already enjoys free access to the European market as an LDC under the EBA-initiative. It also has less interest in the regional market than the smaller EAC member states (Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda) because it trades more with the EU (see ) and South Africa (13.3% of its exports in 2016). On the contrary, not signing the already agreed-on EAC-EPA has two potential advantages for Tanzania. Firstly, the EAC-EPA includes reciprocal trade liberalization, whereas the EBA-initiative grants non-reciprocal access to the European market. Thus, Tanzania would give up its ability to protect its economy against competition with European imports by implementing the EAC-EPA. Secondly, the Tanzanian economy is not complementary to, but competing with the Kenyan economy, as both countries mainly export agricultural products to the European market (Cooksey Citation2016). Both countries’ largest exports to the EU consist of similar products like cut-flowers, tobacco, coffee and tea.Footnote10 If Tanzania keeps on blocking the implementation of the EPA, the probable outcome is that Kenya will have to trade with the EU under the GSP. This would result in Kenyan exports losing competitiveness in relation to Tanzanian exports on the European market. To sum up, Tanzania has strong incentives to retain its privileged trade relations with the EU ahead of a reciprocal trade agreement including its regional neighbours. The reasons for Tanzania to initially go ahead with the negotiations of an EAC-EPA but deciding not to sign it later on, could be a strategic one. Tanzania may have pretended to cooperate in the first stages and prolonged the final implementation later on in order to prevent other EAC member states from agreeing on a profitable trade agreement that threatens Tanzania’s competitiveness on the European market. Tanzania now holds the key that determines the success of the EAC-EPA on which its regional partners depend. The process of the EPA-negotiations and the Tanzanian position seem to affect the intraregional relations of EAC negatively and distrust between the countries grows.Footnote11 Moreover, Kenya has been working on ways to move further with the EPA without the full signatories of all EAC members, which itself could also be problematic for further regional integration in EAC.Footnote12

3.2 ECOWAS

ECOWAS was established in 1975, and currently comprises fifteen member states (see ). The ECOWAS Trade Liberalization Scheme (ETLS) was already set up in 1979 in order to establish a free trade area, but is yet to be fully implemented. Eight French speaking ECOWAS members form the West African Economic and Monetary Union (Union Économique et Monétaire Ouest-Africaine, UEMOA), which has established a customs and monetary union. Six other ECOWAS members (mainly English speaking) form the West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ), which plans to introduce a common currency. In the long-run, the West African states aim to integrate UEMOA and WAMZ towards an ECOWAS customs and monetary union.

Table 2. ECOWAS’ intra and extra-regional trade in 2017.Footnote13

Like in EAC, intraregional trade in ECOWAS is limited. Only 9.6% of member states’ imports and exports are traded on the regional market (see ). Most extra-regional trade takes place with China (44.8%), and with the EU (31.8%), followed at a long distance by India (8%). As expected, ECOWAS’ three big economies – Ghana, Ivory Coast and Nigeria – trade more with the EU than with their smaller neighbours. However, the big economies in West Africa do not constitute attractive markets for their smaller neighbours as is the case in East Africa. Intraregional trade is only dominant in three of ECOWAS’ smaller member states (Gambia, Mali and Togo), a few other member states have comparable trade relations with their neighbours and the EU, and most states trade considerably more with the EU than within the region. Thus, the intraregional gains from regional cooperation should be even lower and the dominance of extra-regional interests even stronger than in EAC.

Most ECOWAS member states have a great interest in access to the European market but, like in the case of EAC, the EU does not treat them equally.Footnote16 First, 11 of the 15 ECOWAS member states qualify as LDC and enjoy non-reciprocal access to the European market under the EBA-initiative. However, the LDCs of ECOWAS are all small member states, whereas the big member states Ghana, Ivory Coast and Nigeria do not profit from the EBA-initiative. ECOWAS’ small LDCs have some interest in the regional market, and they have less economic and political weight to resist pressure from the bigger member states to join the ECOWAS-EPA. Thus, the LDCs of ECOWAS are less likely to pose problems for the EPA negotiations than Tanzania does within EAC. Second, the regional power Nigeria also enjoys privileges in its trade relations with the EU. Due to large oil reserves and successful industrialization, Nigeria has a GDP that is higher than the GDPs of all the other ECOWAS states combined. The regional power trades 39.2% of its total trade value with the EU, whereas its intraregional trade accounts for only 3.7%. Nigeria’s main export is oil, and the EU does not charge any tariffs on oil entering the European market. The total value of Nigeria’s exports to the EU in 2017 was 16.3 billion US dollar of which oil accounted for 15.7 billion US dollar.Footnote17 This means that 96% of Nigeria’s exports to the EU can enter the European market for free. Nigeria thus enjoys a privileged position compared to Ghana and the Ivory Coast.

The three big member states Ghana, Ivory Coast and Nigeria (as well as the small island state Cape VerdeFootnote18), are not LDCs and should have been the driving force behind the EPA negotiations. Indeed, Ghana and the Ivory Coast signed bilateral and interim ‘stepping stone’ EPAs with the EU, which entered into force in 2016. Simultaneously, all ECOWAS member states and Mauritania negotiated a single ECOWAS-EPA, which was agreed in June 2014. Together with the EU, all ECOWAS member states except Gambia and Nigeria signed the agreement in December 2014. The small country Gambia, which trades heavily on the regional market, signed the agreement in August 2018, but the regional power Nigeria refuses to sign and thereby blocks the agreement.Footnote19

Nigeria’s reluctance to sign the ECOWAS-EPA is likely to be the result of its privileged position as an oil-exporting country. The country has shown its reluctance to sign free trade deals.Footnote20 Nigeria does not need to accept reciprocal trade liberalization under the EPA, because its main export product, oil, does not face any tariffs when entering the European market.Footnote21 In contrast, Ghana and the Ivory Coast signed the EPA to secure their access to the European market, while the LDCs signed the agreement due to their interest in intraregional trade or to receive supplemental development aid from the EU. The other ECOWAS member states lack the capacities to push Nigeria into signing the ECOWAS-EPA. Nigeria is the dominant regional power (Omo-Ogbebor and Sanusi Citation2017), and the other ECOWAS member states are dependent on Nigeria for its contributions to ECOWAS. In addition, Nigeria is the region’s main military power and the main contributor to peacekeeping operations in the region. While Nigeria has leverage on the other ECOWAS states, the opposite is not true.

Unlike the case of EAC, the failure to implement a unified EPA does not conflict with the existing level of economic integration in ECOWAS. The REC has not yet agreed on an inclusive customs union, which implies that the member states can still uphold different external trade regimes. Besides, the UEMOA member states, that form a customs and monetary union with each other, were able to keep a unified stance during the EPA negotiations because the defector Nigeria is a member of the rival WAMZ. Nevertheless, the EPA negotiations did not contribute positively to further regional cooperation and integration in West Africa. The goal to unify UEMOA and WAMZ in a single ECOWAS customs union cannot be reached, as long as Nigeria does not harmonize its external trade rules with that of the other ECOWAS member states.

3.3 SADC

Today’s SADC emerged out of its predecessor – the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC) – in 1992. South Africa joined the REC after the end of Apartheid in 1994 (Hentz Citation2005), and currently SADC comprises 16 member states (see ).Footnote22 Almost all SADC member states (except Angola, the DR Congo and the Seychelles) have formed a free trade area since 2008. A more integrated customs union – the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) – exists within SADC between South Africa and the so-called BLNS-countries (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland). SADC adopted a very ambitious integration agenda during the 1990s under which a SADC customs union should have been established in 2010, a common market in 2015, an economic union in 2016 and a monetary union in 2018 (Pallotti Citation2004), but this has not materialised.

Table 3. SADC’s intra and extra-regional trade in 2017.Footnote23

Like in EAC and ECOWAS, intraregional trade is relatively low in SADC (20.1%), and is exceeded by extra-regional trade with the EU (22.8%, see ). The dependence on extra-regional trade is especially high for the bigger economies of Angola and South Africa, whereas the smaller member states also trade significantly on the regional market – meaning most of all with the regional power South Africa. Like Nigeria in ECOWAS, South Africa has a much higher GDP than the other SADC states, and it functions as a trade hub within the region (Muntschick Citation2017; Amos Citation2010). Thus, whereas the regional power South Africa and the oil-exporting Angola are dependent on access to the EU market, the smaller SADC member states need to ensure their access to the regional market. An exception to this clear-cut pattern are the small island economies of Madagascar, Mauritius and the Seychelles, which trade more with the EU than with South Africa.

Three different extra-regional economic privileges exist within SADC. First, roughly half of the SADC member states are LDCs and have access to the European market under the EBA-initiative. However, most of the LDCs – with the exception of Angola and Madagascar – are small member states with strong intraregional trade links to South Africa. Thus, they have a strong interest in the regional market and are unlikely to obstruct the interregional EPA negotiations. Second, like Nigeria in EAC, Angola has huge oil reserves and exports big amounts of this oil to the European market. As a result, Angola’s main export product does not face any tariffs when entering the EU. Finally, South Africa has had its own bilateral trade agreement with the EU since 1999. The TDCA created a free trade area covering 90% of bilateral trade between South Africa and the EU.Footnote25 Consequently, the regional power, which is key for regional cooperation, did not need an EPA in order to ensure access to the European market.

The different extra-regional economic privileges of SADC member states led to a fragmentation of the EPA negotiations. The BLNS-countries plus Angola, Mozambique and Tanzania formed the so-called SADC-minus EPA group. South Africa was initially excluded from the EPA negotiations, but participated in the SADC-minus EPA negotiations from 2006 (Murray-Evans Citation2015; Borrmann, Busse, and de la Rocha Citation2007). Many smaller and less developed SADC member states did not want to join the SADC-minus EPA group in order to avoid being subject to the same liberalization schedule as the more industrialized South Africa (Vickers Citation2011; Meyn Citation2004). Consequently, half of the SADC countries negotiated an EPA with five other Eastern and Southern African (ESA) states, the DR Congo joined the Central Africa-EPA together with seven Central African states, and Tanzania left the SADC-minus group in 2007 to join the EAC-EPA group. Thus, SADC split up over four different EPAs, which made the harmonization of external trade regimes impossible.

Even the negotiations of the shrunken SADC-minus EPA group were cumbersome, resulting in an interim agreement with Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland and Mozambique signed in 2007.Footnote26 Until 2016, South Africa refused to sign any new agreement with the EU and relied on the TDCA. Consequently, the regional power did not provide the necessary leadership in order to pull the other SADC member states into a common EPA group by taking the lead in the negotiations and compensating smaller member states for possible losses (Muntschick Citation2017). The opposite was true: South Africa halted the negotiations and refused to consider interregional liberalization in areas like services and investment. Some of the smaller SADC member states would have been open to negotiate these issues with the EU, but they were not willing to risk the customs union with South Africa (Vickers Citation2011). Only when the terms of the SADC-EPA moved closer to an improved version of the TDCA, South Africa became more cooperative and eventually signed the EPA in 2016 (Berends Citation2016).Footnote27,Footnote28 Thus, the SADC-minus group finally succeeded in signing an EPA, which looked very similar to the old TDCA, in June 2016. The liberalisation schedule of the SADC-minus EPA was only a minor problem for the BLNS-countries, because they form a customs union with South Africa (SACU) and consequently already had to implement the previous TDCA-rules (Murray-Evans Citation2015; Meyn Citation2004). The SADC-minus EPA thus reaffirmed the common external tariff of SACU.Footnote29

Mozambique, an LDC and the poorest country in the region, is not a SACU member state, but has a large interest in intra-regional trade, especially in trade with South Africa (27,1% of its trade is within the region). Thus, its motivation to join the SADC-minus EPA is likely to be based on its interest in regional integration, namely in the flexible rules of origin and in the cooperation on regulatory standards to boost its exports.Footnote30 Only Angola, which enjoys a privileged position as an LDC and as an oil-exporter, decided not to sign the EPA, but it can join the agreement in the future.Footnote31

The EPA negotiations were not in conflict with the already established SADC-FTA, and at least the unity of SACU was preserved within the SADC-minus group. However, further economic integration in the entire SADC was made impossible by the fragmentation of the region’s external trade regime (Muntschick Citation2017). A SADC customs union could not be established in 2010 because it would have required the harmonization of the region’s external trade rules towards the EU. And because the SADC customs union was not implemented, further integration towards a common market, an economic union and a monetary union became obsolete. Thus, the EPA negotiations had a long-lasting negative impact on regionalism in Southern Africa.

4. Conclusion

EAC, ECOWAS and SADC have been unable to build up coherent and stable EPA groups in their trade negotiations with the EU. This is due firstly to the fact that large African economies like Tanzania, Nigeria or South Africa have already enjoyed privileged access to the European market without implementing the unpopular EPAs. In its external trade and development policies, the EU differentiates between least developed countries, developing countries, advanced economies like South Africa and the import of highly-demanded raw materials like oil. This differentiation leads to extra-regional economic privileges for some African countries. Moreover, Tanzania’s, Nigeria’s and South Africa’s intraregional trade share is much lower than that of smaller regional member states, which means that the regional powers have no interest in access to the regional market either. Small privileged countries like Rwanda in East Africa, Togo in West Africa or Mozambique in Southern Africa nevertheless participate in EPAs because they have a genuine interest in African regionalism, but large privileged countries obstruct the EPAs in order to protect their privileges. Tanzania, the second largest economy of the EAC, qualifies as an LDC and enjoys free access to the European market under the EBA-initiative. By blocking the implementation of the EAC-EPA, Tanzania avoids reciprocal trade liberalization and gains a competitive advantage on the European market in relation to the exports of its neighbour Kenya. Nigeria, a regional power, mainly exports oil to the European market, where this commodity does not face any import tariffs. Nigeria can afford to reject the ECOWAS-EPA in order to avoid opening up its own domestic market. SADC became completely fragmented during the EPA negotiations, because it included several privileged member states. Half of SADC’s member states are LDCs, Angola is an oil-exporting country and – most importantly – the regional power South Africa enjoyed the bilateral TDCA with the EU. In the end, only the SACU member states and Mozambique joined the SADC-minus EPA, whereas the other SADC member states joined other EPA groups.

The incongruence of EPA-groups and the membership of RECs poses a problem for deeper regional integration in Africa. The establishment of customs unions requires that REC members to harmonise their external trade regimes which is almost impossible if they do not implement single and coherent EPAs. EAC’s customs union is put at risk by Tanzania’s refusal to sign the EPA, a full ECOWAS customs union cannot be established without cooperation of the regional power Nigeria, and the planned SADC customs union could not be established in 2010. Without being able to establish customs unions, deeper regional integration towards economic and monetary unions becomes highly unlikely in Africa. Thus, instead of deepening regional integration within the different African RECs, African countries recently seem to opt for more shallow trade agreements on a larger scale. In 2015, the member states of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), EAC and SADC agreed to form the so-called Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA), which should allow for free trade from the Cape to Cairo. Similarly, 44 of the 55 member states of the African Union (AU) – excluding the important regional powers Nigeria and South Africa – signed an agreement in March 2018 to establish an African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Such free trade agreements are less affected by extra-regional economic relations of some member states, because they do not harmonise the external trade regimes and allow for member states’ independent external trade policies.

The negative impact of the EPA-negotiations on African regionalism contradicts the EU’s support of regional integration in other world regions (Draper Citation2007). The EU claims that regionalism is a necessary tool to create economic development, and it consequently supports regional initiativesFootnote32 and institutions in the global south (Lenz Citation2011; Söderbaum, Stålgren, and van Langenhove Citation2005). The EPAs were also planned to support African regionalism, because the EU aimed to negotiate with regional groups of ACP-countries, contrary to single countries individually. However, instead of unifying EAC, ECOWAS and SADC further, the EPA negotiations and the privileged positions of some REC members split the regions and built up further obstacles for deeper economic integration. Such privileged relations with the EU do not only exist for member states of African RECs, but they are a more general phenomenon of regionalism in the global south. For example, Brazil signed a bilateral strategic partnership agreement with the EU in 2007. So far, this agreement excludes trade issues in order not to endanger the customs union of the South American Common Market (MERCOSUR). However, the interregional trade negotiations between the EU and MERCOSUR have moved slowly for almost 20 years, and were only recently finalised . The EU also started bilateral trade negotiations with single member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nation (ASEAN) in 2010. Although these bilateral agreements are deemed to be a stepping-stone for an interregional trade agreement between ASEAN and the EU, it has yet to be seen, whether this can be realized, or whether the bilateral trade agreements prevail and become a problem for regionalism in Southeast Asia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. European Commission: ‘Everything But Arms’ (http://trade.ec.europa.eu/tradehelp/everything-arms).

2. EU Tariffs on imports to the single market can be obtained at: http://madb.europa.eu/madb/euTariffs.htm.

3. We exclude South Sudan from the following analysis, because there is barely any data available, and the country plays only a marginal role in EAC. South Sudan joined the REC only recently and is currently struggling with a civil war and a famine.

4. Trade numbers obtained from trade map (www.trademap.org), an online database that relies mainly on UN Comtrade data.

5. GDP numbers obtained from the Worldbank (data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD).

6. The signature of South Sudan is not yet required, because the country joined EAC after the EPA negotiations ended and is still formalising its EAC membership.

7. The Monitor: ‘East Africa: Uganda Struggles to Deliver EPA to Success’ (allafrica.com/stories/201703010049.html).

8. Council of the European Union: ‘Burundi: EU Closes Consultations under Article 96 of the Cotonou Agreement’ (www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/14-burundi-eu-closes-consultations-cotonou-agreement).

9. The East African: ‘Tanzania allowed 4 months to resolve EPA impasse’ (www.theeastafrican.co.ke/business/Tanzania-allowed-4-months-to-resolve-EPA-impasse/2560-4975576-100d0i1z/index.html).

10. Export profiles obtained from trade map (www.trademap.org).

11. Forbes Africa: ‘Elusive Trade Deal Split East Africa’ (https://www.forbesafrica.com/investment-guide/2017/04/01/elusive-trade-deal-split-east-africa/).

12. The East African: ‘EPA: Test of unity as Kenya breaks away’ (www.theeastafrican.co.ke/business/EPA-test-of-unity-as-Kenya-breaks-away-/2560-4954710-aul875/index.html).

13. Trade numbers obtained from trade map (www.trademap.org). No recent data for Guinea-Bissau. Most recent data for Guinea-Bissau is from 2005.

14. GDP numbers obtained from the Worldbank (data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD).

15. Excluding Guinea-Bissau.

16. European Commission: ‘The Economic Impact of The West Africa – EU Economic Partnership Agreement: An analysis prepared by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Trade’ (trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/april/tradoc_154422.pdf).

17. Trade numbers obtained from trade map (www.trademap.org).

18. Cape Verde graduated from LDC status in 2008 and lost its EBA access to the EU in 2011 after a transition period of three years. Since 2011 Cape Verde enjoys enhanced access to the EU under the GSP+.

19. Business Times: ‘Buhari: Why Nigeria Is Yet To Sign Economic Partnership Agreement With EU’ (www.businesstimes.com.ng/buhari-why-nigeria-is-yet-to-sign-economic-partnership-agreement-with-eu/).

20. CNN: ‘Nigeria rejects West Africa-EU free trade agreement’ (edition.cnn.com/2018/04/06/africa/nigeria-free-trade-west-africa-eu/index.html).

21. Leadership: ‘Pressure To Sign Economic Partnership Agreement’ (leadership.ng/2017/08/07/pressure-sign-economic-partnership-agreement/).

22. The Comoros are the newest member state and joined SADC in 2016. Because the Comoros were not a member state of SADC during the EPA negotiations, they are disregarded in this study.

23. Trade numbers obtained from trade map (www.trademap.org).

24. GDP numbers obtained from the Worldbank (data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD).

25. European Commission: ‘Countries and Regions: South Africa’ (ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/south-africa).

26. European Commission: ‘The Southern African Development Community (SADC) EPA’ (ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/developing-countries/acp/sadc_en.pdf).

27. The upgrade consists of full liberalization of the fish sector and improved commitments from the EU on tariff lines under tariff rate quota (TRQ) for certain products (Berends Citation2016).

28. Media statement of the Department of Trade and Industry of the Republic of South Africa and the European Union Delegation to the Republic of South Africa (www.thedti.gov.za/editmedia.jsp?id=3867).

29. European Commission: ‘The Economic Impact of the SADC EPA Group – EU Economic Partnership Agreement: An analysis prepared by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Trade’ (trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/june/tradoc_154663.pdf).

30. Ibid.

31. European Commission: ‘The Southern African Development Community (SADC)’ (ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/regions/sadc).

32. European Commission International Cooperation and Development, ‘Funding for Regional Integration’ (https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sectors/economic-growth/regional-integration/funding_en).

References

- Amos, S. 2010. “The Role of South Africa in SADC Regional Integration: The Making or Breaking of the Organization.” Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology 5: 124.

- Berends, G. 2016. “‘what Does the EU-SADC EPA Really Say? an Analysis of the Economic Partnership Agreement between the European Union and Southern Africa.” South African Journal of International Affairs 23: 457–474. doi:10.1080/10220461.2016.1275763.

- Borrmann, A., M. Busse, and M. de la Rocha. 2007. “Consequences of Economic Partnership Agreements between East and Southern African Countries and the EU for Inter- and Intra-regional Integration.” International Economic Journal 21: 233–253. doi:10.1080/10168730701345398.

- Buzdugan, S. R. 2013. “Regionalism from Without: External Involvement of the EU in Regionalism in Southern Africa.” Review of International Political Economy 20: 917–946. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.747102.

- Claar, S., and A. Nölke. 2013. “Deep Integration in North-South Relations: Compatibility Issues between the EU and South Africa.” Review of African Political Economy 40: 274–289. doi:10.1080/03056244.2013.794726.

- Cooksey, B. 2016. “Tanzania and the East African Community: A Comparative Political Economy.” (Discussion Paper 186, European Centre for Development Policy Management, Maastricht).

- Doidge, M. 2007. “Joined at the Hip: Regionalism and Interregionalism.” Journal of European Integration 29: 229–248. doi:10.1080/07036330701252474.

- Draper, P. 2007. “EU-Africa Trade Relations: The Political Economy of Economic Partnership Agreements” (Jan Tumlir Policy Essays, No. 02/2007, European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE), Brussels).

- Elgström, O., and J. Pilegaard. 2008. “Imposed Coherence: Negotiating Economic Partnership Agreements.” Journal of European Integration 30: 363–380. doi:10.1080/07036330802141949.

- Farrell, M. 2005. “A Triumph of Realism over Idealism? Cooperation between the European Union and Africa.” Journal of European Integration 27: 263–283. doi:10.1080/07036330500190107.

- Fawcett, L., and H. Gandois. 2010. “Regionalism in Africa and the Middle East: Implications for EU Studies.” Journal of European Integration 32: 617–636. doi:10.1080/07036337.2010.518719.

- Fink, S. 2017. “Trade Network Analyses.” In Regional Integration in the Global South: External Influence on Economic Cooperation in ASEAN, MERCOSUR and SADC, edited by S. Krapohl, 91–112. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Forwood, G. 2001. “The Road to Cotonou: Negotiating a Successor to Lomé.” Journal of Common Market Studies 39: 423–442. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.00297.

- Frennhoff Larsén, M. 2007. “Trade Negotiations between the EU and South Africa: A Three-Level Game.” Journal of Common Market Studies 45: 857–881. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00751.x.

- Gartzke, E., Q. Li, and C. Boehmer. 2001. “Investing in the Peace: Economic Interdependence and International Conflict.” International Organization 55: 391–438. doi:10.1162/00208180151140612.

- Haastrup, T. 2013. “EU as Mentor? Promoting Regionalism as External Relations Practice in EU-Africa Relations.” Journal of European Integration 35: 785–800. doi:10.1080/07036337.2012.744754.

- Haftel, Y. Z. 2007. “Designing for Peace: Regional Integration Arrangements, Institutional Variation, and Militarized Interstate Disputes.” International Organization 61: 217–237. doi:10.1017/S0020818307070063.

- Hallaert, J.-J. 2010. “Economic Partnership Agreements: Tariff Cuts, Revenue Losses and Trade Diversion in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of World Trade 44: 223–250.

- Hentz, J. J. 2005. “South Africa and the Political Economy of Regional Cooperation in Southern Africa.” Journal of Modern African Studies 43: 21–51. doi:10.1017/S0022278X0400059X.

- Hurt, S. R. 2012. “The EU-SADC Economic Partnership Agreement Negotiations: ‘locking In’ the Neoliberal Development Model in Southern Africa?” Third World Quarterly 33: 495–510. doi:10.1080/01436597.2012.657486.

- Ilorah, R., and C. C. Ngwakwe. 2015. “Economic Partnership Agreements between African-Caribbean-Pacific Countries and the European Union: Revisiting Contested Issues.” Journal of African Business 16: 322–338. doi:10.1080/15228916.2015.1089689.

- Krapohl, S. 2017. “Two Logics of Regional Integration and the Games Regional Actors Play.” In Regional Integration in the Global South: External Influence on Economic Cooperation in ASEAN, MERCOSUR and SADC, edited by S. Krapohl, 33–62. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Krapohl, S., and S. Fink. 2013. “Different Paths of Regional Integration: Trade Networks and Regional Institution-Building in Europe, Southeast Asia and Southern Africa.” Journal of Common Market Studies 51: 472–488. doi:10.1111/jcms.12012.

- Krapohl, S., K. L. Meißner, and J. Muntschick. 2014. “Regional Powers as Leaders or Rambos of Regional Integration? Unilateral Actions of Brazil and South Africa and Their Negative Effects on MERCOSUR and SADC.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52: 879–895. doi:10.1111/jcms.12116.

- Langan, M., and S. Price. 2015. “Extraversion and the West African EPA Development Programme: Realising the Development Dimension of ACP-EU Trade?” Journal of Modern African Studies 53: 263–287. doi:10.1017/S0022278X15000579.

- Lenz, T. 2011. “Spurred Emulation: The EU and Regional Integration in Mercosur and SADC.” West European Politics 35: 155–173. doi:10.1080/01402382.2012.631319.

- Mattheis, F., and U. Wunderlich. 2017. “Regional Actorness and Interregional Relations: ASEAN, the EU and Mercosur.” Journal of European Integration 39: 723–738. doi:10.1080/07036337.2017.1333503.

- Meyn, M. 2004. “Are Economic Partnership Agreements Likely to Promote or Constrain Regional Integration in Southern Africa?” In Monitoring Regional Integration in Southern Africa Yearbook, edited by D. Hansohm, W. Breytenbach, T. Hartzenberg, and C. McCarthy, 29–58. Vol. 4. Windhoek: Namibian Economic Policy Research Unit.

- Muntschick, J. 2017. “SADC.” In Regional Integration in the Global South: External Influence on Economic Cooperation in ASEAN, MERCOSUR and SADC, edited by S. Krapohl, 179–208. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Murray-Evans, P. 2015. “Regionalism and African Agency: Negotiating an Economic Partnership Agreement between the European Union and SADC-Minus.” Third World Quarterly 36: 1845–1865. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1071659.

- Omo-Ogbebor, D. O., and A. H. Sanusi. 2017. “Asymmetry of ECOWAS Integration Process: Contribution of Regional Hegemon and Small Country.” Vestnik RUDN International Relations 17: 59–73. doi:10.22363/2313-0660-2017-17-1.

- Pallotti, A. 2004. “SADC: A Development Community without A Development Policy?” Review of African Political Economy 31: 513–531. doi:10.1080/0305624042000295576.

- Slocum-Bradley, N., and A. Bradley. 2010. “Is the EU’s Governance ‘good’? an Assessment of EU Governance in Its Partnership with ACP States.” Third World Quarterly 31: 31–49. doi:10.1080/01436590903557314.

- Söderbaum, F., P. Stålgren, and L. van Langenhove. 2005. “The EU as A Global Actor and the Dynamics of Interregionalism: A Comparative Analysis.” Journal of European Integration 27: 365–380. doi:10.1080/07036330500190297.

- Stevens, C. 2006. “The EU, Africa and Economic Partnership Agreements: Unintended Consequences of Policy Leverage.” Journal of Modern African Studies 44: 441–458. doi:10.1017/S0022278X06001844.

- Stevens, C. 2008. “Economic Partnership Agreements: What Can We Learn?” New Political Economy 13: 211–223. doi:10.1080/13563460802018562.

- Vickers, B. 2011. “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Small States in the EU-SADC EPA Negotiations.” The Round Table 100: 183–197. doi:10.1080/00358533.2011.565631.

- Woolcock, S. 2014. “Differentiation within Reciprocity: The European Union Approach to Preferential Trade Agreements.” Contemporary Politics 20: 36–48. doi:10.1080/13569775.2014.881603.

- World Bank. 2000. Trade Blocs: A World Bank Policy Research Report. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Yu, W., and T. V. Jensen. 2005. “Tariff Preferences, WTO Negotiations and the LDCs: The Case of the ‘everything but Arms’ Initiative.” World Economy 28: 375–405. doi:10.1111/twec.2005.28.issue-3.