ABSTRACT

This article examines the emotions-policy nexus within the EU’s foreign policy, specifically focusing on the EU’s human rights sanctions against China and North Korea. By embedding the discussion within an extended framework of analysis that underscores the emotional dimensions of the EU’s foreign policy, the article scrutinizes how policy decisions, unfolding through a series of actions, reactions and third-party responses, shape, and are shaped by, emotional chains via its enabling and constraining mechanisms. While the case study of China illustrates the two mechanisms via exploring the EU-China investment negotiations, human rights sanctions as well as China’s retaliatory measures and the EU’s response, the case of North Korea, using the same sanctions, shows a divergent policy response and absence of emotions albeit within a similar rhetoric. The conclusion ponders over the efficacy of sanctions policies, suggesting that the integration of emotional awareness into policy-making can foster a more holistic approach in international politics.

When the European Union (EU) imposed sanctions on China (PRC) and North Korea (DPRK) due to serious human rights violations in March 2021, the subsequent statements by both governments exhibited a striking similarity, implying the EU’s interference in respective countries’ internal affairs and threatening the EU with serious consequences: the quotes above illustrate these two nearly identical rhetorical responses by spokespersons of Chinese and North Korean ministries of foreign affairs to the EU’s restrictive measures. Yet the actions by these third parties and reactions by the EU that followed in each case took divergent paths. The key puzzle for this article therefore is: how come the display of similar emotions encapsulated in these initial reactions led to different policy decisions? Moreover, these two cases also lay the ground for examining the pivotal role of emotions in shaping, propelling and sometimes constraining EU foreign policy, especially when norm violations are at the forefront.

Anchored within the fields of political psychology and international relations, emotions have recently emerged not merely as ancillary phenomena but as crucial explanatory tools generating understanding for why certain courses of action in foreign policy are taken and why others are not. The complex emotional networks embedded in the EU’s relations with China and North Korea provide a rich material from which to explore the multifaceted and intertwining dynamics between the emotions and policy decisions, particularly in the context of sanctions in response to perceived or actual norm violations. Thus, this article seeks to delve into the emotional ecosystems that drive and are shaped by the policies, reactions and intricate relationships entangling the EU with China and North Korea.

Central to our exploration are the following overarching questions: How do emotions influence EU foreign policy, especially in the face of norm violations? What actions, or non-actions, are pursued by the EU in such contexts? How do these emotions, and the actions they induce, provoke emotions and reactions from third countries, thereby engendering a subsequent response or non-response by the EU? These queries set the stage to dissect the complex roles emotions play in crafting and at times hindering the policies and actions in the EU’s interactions not only with its partners but primarily with its adversaries as the two case studies of EU-China and EU-North Korea relations illustrate.

Following this introduction, the article outlines an extended framework of analysis predominantly drawing upon, and expanding on, the framework of analysis for understanding the role of emotions in EU foreign policy as outlined in the Introduction to this special issue (SI) by Seda Gürkan and Özlem Terzi. Gürkan and Terzi’s exploration into the emotional mechanisms operating within international relations and focus on the influence of emotions on EU policy-making offer a robust foundation to analyze and comprehend the emotional dynamics at play in the context of EU’s sanction policies and its relations with China and North Korea. The ensuing extended framework serves as a lens through which the intertwining emotional and policy elements in the two case studies can be thoroughly examined, providing a coherent theoretical pathway to understand the nuanced and multilayered emotional-policy landscapes. The extended framework envisions a chain of emotions and reactions, or non-reactions, among involved parties, making it not a one-way but a two-way street interaction with a series of steps or actions.

Pivoting to the first case study, the article dissects the intricacies of the EU-China relations after the EU has for the first time implemented its so-called European Magnitsky Act in March 2021. This segment scrutinizes the emotional ‘enabling’ and ‘constraining mechanisms’ and policy responses embedded within the multidimensional EU-China interactions. It particularly considers the post-2021 period when the emotional and policy interactions between the two entities encountered significant perturbations following the imposition of sanctions against China by the EU for human rights violations and the Chinese retaliation which, in turn, led to another retaliatory measure by the European Parliament (EP). The emotions of anger, indignation and assertiveness which permeate the official statements and actions are examined in light of the extended framework of analysis.

Transitioning to the second case study, the article navigates through the relatively opaque waters of the EU-North Korea relations. Notwithstanding the comparative lack of weight of Pyongyang in contrast to Beijing on the global stage, the emotions displayed within North Korea’s interactions with the EU, particularly following the imposition of the same Magnitsky sanctions, illuminate a contrasting emotional and policy responses when juxtaposed against the EU-China narrative. This section elucidates the emotional responses and policy reactions (or their lack of) that unfolded (or not) following the use of the EU’s Magnitsky Act against North Korean officials. While exploring the ‘constraining mechanism’ and ‘absence of emotions’, potential motivations within North Korea’s responses and actions are explored following the EU’s emotional (non)-action.

In the final section, the article seeks to compare and contrast the commonalities and divergences threading through the EU’s emotional interactions with China and North Korea. To conclude, the article synthesizes the insights into emotional reactions triggered by sanctions, exploring not just the nuances of the emotions-policy nexus but also pondering upon the implications and potential future trajectories of sanctions policies in the EU, particularly with the backdrop of an increasingly intensifying US-China competition. The revelations gleaned from the preceding exploration inform an understanding of how emotions, while often relegated to the peripheries of policy discussions, are indeed seminal in influencing, shaping and occasionally constraining policy formulations and diplomatic interactions. By unravelling the emotional dynamics and policy interplays within the EU’s relationships with China and North Korea, the article aims to offer nuanced perspectives into what multilayered roles emotions play in the realms of EU foreign policy, sanctions and international politics more broadly.

An extended framework of analysis for understanding the role of emotions in EU foreign policy

Emotions have gained prominence as a critical element in understanding the dynamics of EU foreign policy. Scholars (Clément and Sangar Citation2018; Koschut Citation2020, Gürkan and Coman Citation2021; Pace and Bilgic Citation2018; Sanchez Salgado Citation2021b, Citation2021b; Smith Citation2021; Terzi, Palm, and Gürkan Citation2021; van Rythoven and Solomon Citation2020) have increasingly recognized that emotions play a significant role in shaping the actions and decisions of both individual actors within the EU institutions and the EU as a collective entity. Emotions, such as anger, empathy or fear are acknowledged as influential factors in diplomatic interactions. These emotions can arise from various sources, including from norm violations, human rights abuses or security threats.

Emotions are often tied to the normative background of the EU (Manners Citation2021). For instance, as will also be elaborated on the case studies within this article, the violation of human rights can trigger emotional responses within the EU institutions, as they are committed to upholding human rights as a core value. Individual actors within the EU, including policymakers, diplomats and leaders, are not immune to emotional responses. Their emotional states can significantly impact the direction of EU foreign policy, as demonstrated by the case of China’s treatment of the Uyghur minority where anger toward norm violations, and empathy for affected populations, led to specific policy choices.

Emotions can thus spread and influence decision-making processes within the EU. When key actors, including top officials on behalf of EU institutions, express strong emotions, it can create a domino effect, shaping the overall emotional tone of EU foreign policy discussions. Emotions can therefore drive the EU to take action in response to external events. For instance, moral outrage at human rights violations can lead to the imposition of sanctions as we will see later in the next sections, while empathetic responses might drive humanitarian assistance efforts. Such a dual situation has developed in the EU’s ‘critical engagement’ policy towards North Korea (Novotná and Ford Citation2019) that will be discussed later in this article and its population which is suffering both from human rights abuses and food shortages. Nonetheless, we can also see similar examples in other parts of the world, from Ukraine (as discussed in other contributions to this SI) through the Middle East up to Cuba and Venezuela where both feelings of anger and solidarity are simultaneously at play.

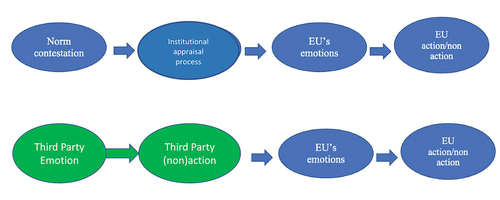

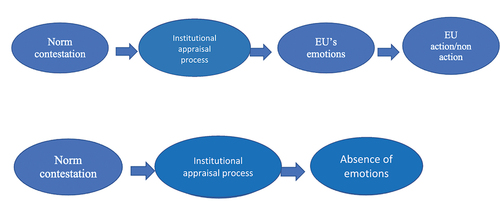

Central to our discussion about emotions in EU foreign policy is the concept of norm contestation. An international norm violation induces an institutional appraisal process (Gürkan and Terzi Citation2024) in the EU which may evoke emotions among EU actors. For instance, when a third country breaches an international norm such as protection of human rights or territorial integrity, an institutional appraisal process will take place which may elicit emotions from the EU, prompting action or inaction. Emotions therefore stand out as pivotal, not merely as responsive, elements but as shapers of policy actions, particularly as a result of the institutional appraisal process.

During the institutional appraisal process, whenever we observe a situation in which emotions translate into action, we will call this an ‘enabling mechanism’. However, should the emotions turn into a non-action, or a lack of action, we will consider this a ‘constraining mechanism’, giving rise to the concept of an ‘emotion-action gap’ (Smith Citation2021) where an action would be expected but it does not happen. Nonetheless, there is also a third alternative where a norm violation does not produce either emotion (or action) which is an indicator of the absence of emotions. In other words, in this configuration the actor just does not care. below illustrates this process in a simplified manner which is described in a closer detail in the Introduction to this SI.

Figure 1. A simplified model of international norm violation leading to the institutional appraisal process which may induce EU’s emotions and, subsequently, its action or non-action.

The simplified model above provides a foundation to investigate the relationship between EU’s emotional responses and its subsequent actions in the international arena. Nonetheless, our analysis does not stop here. As much as the EU’s foreign policy is shaped by its emotions, foreign policies of other states and international actors are influenced by their emotions, too. Emotions – and emotionally-led policy decisions – within EU foreign policy can trigger reactions from third parties, such as target states or international actors. The way in which the EU expresses its emotions eliciting actions therefore leads to counter-responses, further enhancing the emotional dynamics in international arena.

The EU’s actions/non-actions thus stimulate emotions in the third parties, leading to their subsequent emotional responses and actions/non-actions and further impacting the original actor’s (e.g. EU) emotional and policy decisions. Consequently, there’s an intricate cycle where emotions instigated by third state actions influence yet again EU foreign policy, leading to further emotional reactions, thus generating chains of reactions which either provoke actions or result in inaction while establishing a cyclical dynamic.

This yields a bracelet-like chain, where emotions and actions continuously shape and reshape one another in a sequence of enabling and constraining mechanisms. This complex chain creates a ripple effect where emotions spur specific EU foreign policy actions (or non-actions), which then incite emotions in other foreign policy actors, thereby leading to their actions (or non-actions) and impacting back the EU which then reacts (or not) based on its new set of emotions. The key rationale of this article is therefore to contribute to understanding how the role of emotions in EU foreign policy is essential for comprehending the chain of reactions that ensue when norm violations occur and how emotions serve as enabling and constraining mechanisms through a series of interconnected emotional and policy response chains.

This cyclicality of emotions leading to actions, which in turn spark new emotions, is encapsulated in the extended framework of analysis that builds on the simplified model above as well as on the overall framework of analysis as posited in the Introduction to this SI (Gürkan and Terzi Citation2024). Unlike earlier models that delineate a linear progression from norm violation through institutional appraisal process to emotional response, this approach advocates for a multi-layered perspective in which emotions and reactions can act in a chain-like, recursive manner, affecting both initial actors and third parties.

visualizes this extended framework of analysis in which the ensuing emotional and action-based reactions create a loop, affecting not just third parties but also the primary entity. These chains of reactions, which elicit responses or non-responses from involved entities, generate subsequent emotions and actions that further impact the EU’s diplomatic relations and policy decisions, adding a layer of complexity to the initial process or event. As demonstrates, the extended framework of analysis does not consider emotional responses just as singular, one-dimensional reactions but as evolving responses in an interconnected web of international relations. This approach transcends merely observing a norm violation-institutional appraisal process-emotion-response pattern and introduces a more complex, multi-step emotions-policy nexus, examining how each action or non-action generates a set of new emotions, affecting not just immediate third parties but also the initial actors themselves. Emotions herein are evaluated for their dual role – as a two-way street of emotional chain reactions – influencing the EU’s actions and policies.

As shown in , an intricate chain formed by emotions, policy decisions and responses, especially as a result of norm violations, unveils a complex interplay that is crucial to effective policy-making in EU foreign policy. Exploring the multi-faceted emotions-policy nexus will be further elucidated in this article on distinct case studies of the EU’s responses to norms violations in China/PRC and North Korea/DPRK. Despite apparent similarities in norm violations, notably, human rights abuses, and comparable initial reactions (targeted sanctions) by the EU towards China and North Korea, the ensuing emotional and action chains diverge significantly, as we will see in the next two sections.

Nonetheless, despite these dissimilarities in third-party reactions, the subsequent emotional-affective and policy shifts within the EU foreign policy manifest a complex, intertwined relationship between emotions and policy actions. The dual case studies illustrate that emotions not only create an initial response but also instigate a subsequent chain of emotions and actions, highlighting the imperative to explore beyond a singular emotional instance, and instead to scrutinize the interconnected emotional and policy dynamics. This article underscores the importance of evaluating emotions as a key element which is intertwined in a chain of actions and reactions, and which is pivotal to understanding the unfolding international crises, policy formulations and policies such as imposition of sanctions. In deciphering the complex web of emotions and diplomatic (non)actions, the next two sections explore the interaction of EU sanctions, emotional responses and subsequent actions or non-actions within international interactions with China and North Korea.

Given the article’s focus on emotions leading up to, and third-party emotional responses to, the imposition of autonomous sanctions by the EU, the article additionally contributes to the literature on sanctions, highlighting the role of emotions such as anger and resentment when levying and countering sanctions, especially when these sanctions could be seen as a symbolic form of punishment (Onderco Citation2024) rather than a tool of policy enforcement.

The case of EU-China relations: evaluating the emotional dimensions in the EU’s human rights sanctions towards China

In the previous section, we have outlined how emotions influence EU foreign policy more broadly, resulting from the institutional appraisal process following a norm violation. In this section, we will examine the specific case study of EU-China relations which exemplifies how policy decisions, unfolding through a series of actions, reactions and third-party responses, shape, and are shaped by, emotions and emotional chains via its enabling and constraining mechanisms. In the context of EU-China relations, the section will navigate through the negotiations over the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) and the EU sanctions imposed in 2021 due to human rights violations as well as China’s retaliatory measures and the EU’s response. Using the backdrop of EU-China relations, this section explicates the interplay of emotional reactions and subsequent policy actions, emphasizing the bidirectional influence between emotions and political decision-making.

Negotiations over an investment treaty between the EU and China have been ongoing for several years. However, in the latter half of 2020 under the German EU rotating presidency, there was a concerted effort to wrap them up in order to rebalance EU-China relations. Chancellor Angela Merkel, a driving force behind these efforts, intended to strike a deal to bolster the standing of German (and European) industries on the Chinese market, all within the context of post-pandemic economic recovery (Telò Citation2021) and US President Trump’s fraught relationship with China. The CAI agreement was aimed to enhance market access in China for European businesses across various sectors, including the automotive, manufacturing, financial, telecommunications, health and R&D, and to limit forced technology transfers and subsidies for Chinese state-owned enterprises, while embedding sustainable development provisions. As has been argued elsewhere (Novotná Citation2022a), for Merkel, CAI was to be a pinnacle achievement of her last EU Presidency and her 16-year tenure leading Germany, and arguably, Europe.

During the course of the German EU Presidency, Chancellor Merkel planned an in-person meeting between President Xi and 27 EU leaders for September 2020 in Leipzig which was eventually canceled due to COVID-19 health and safety concerns. However, the EU conducted unprecedented three virtual summits with China within approximately six months, one of which replaced the canceled Leipzig meeting. By the close of the year and after 35 negotiation rounds, Beijing and Brussels, with strong backing from Berlin and Paris, agreed in principle on CAI, a pact under development for almost eight years since the initial decision to commence EU-China negotiations in February 2012 which then officially began in 2013.

Although Berlin undeniably drove the final push to conclude CAI, the motivation extended beyond bilateral trade relations with Beijing, especially in light of the increasing US-China rivalry. The investment agreement sought to ensure that European businesses could enjoy similar benefits to those garnered by the U.S. through Donald Trump’s ‘phase one deal’ with Beijing – particularly as the Biden administration was poised to take office. In essence, CAI was as much an endeavor to level the European playing field with the US as with China (Friedlander Citation2020). Moreover, Merkel coordinated closely with French President Emmanuel Macron, aiming to strengthen the EU’s position and ensure a more unified approach vis-à-vis China, with the view of ratifying CAI during the French EU Presidency in the first half of 2022. This coordination between Germany and France, as the two most influential EU member states, was essential for successful completion of the agreement.

Nonetheless, CAI was not merely an economic enterprise but represented a practical implementation of the two streams of the EU’s three-pronged approach to Beijing, as earlier announced in the ‘EU-China Strategic Outlook’ (European Commission, and EEAS Citation2019). This strategy casts China simultaneously as a cooperation partner, an economic competitor and a systemic rival, with the investment deal primarily addressing the first two roles. From the emotional standpoint, there was a sense of hope and anticipation among EU leaders and officials, as well as a sense of relief of bringing the long-winded negotiations with China to a close as social media posts by the German EU Presidency around the Christmas period of 2020 indicate.Footnote1

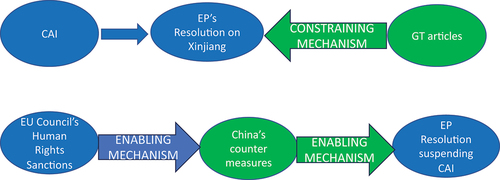

However, the EU has also implemented the third element of its EU-China strategy – known as ‘systemic rivalry’ – focusing on human rights. Parallel to the CAI negotiations, the European Parliament (EP) passed a resolution on 17 December 2020, addressing forced labour and the situation of the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (European Parliament Citation2020). Simultaneously, the Council adopted a Decision which set up a framework for targeting serious human rights abuses worldwide, establishing the EU global human rights sanctions regime on 7 December 2020 (Council of the European Union Citation2020).

In contrast to the German EU Presidency’s upbeat statements about CAI, the EP resolution on human rights violations in Xinjiang uses strongly worded language, ‘deeply deploring’ (1×), being ‘strongly concerned’ (1×), ‘expressing strong concern’ (2×) ‘strongly condemning’ (2×), ‘calling on’ the Chinese (2×), ‘requesting’ China (1×), ‘criticizing’ (1×) and ‘urging’ (2×) China to improve the situation in Xinjiang. The EP resolution also welcomes the adoption of the EU Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime while calling for maximum use of it. Additionally, it advocates for the inclusion of forced labour provisions in CAI. While there were calls for an EU ban on products made with Uyghur forced labour (S&D Group Citation2020), these did not gain enough traction in 2020. Although forced labour regulation was already proposed by the European Commission in September 2022 (Ellena Citation2023), the Council has adopted a mandate for negotiations with the EP only in January 2024 (Council of the European Union Citation2024).

The Chinese response was swift and assertive. The next day, on 18 December 2020, the Global Times (Citation2020b), a major state-run English-language Chinese newspaper, released an editorial mocking the EP’s resolution and Raphaël Glucksmann, one of the French MEPs behind the draft, denying any wrongdoings in Xinjiang and pointing to slanderous content of the resolution. Nonetheless, given the CAI negotiations nearing its finish, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin (Global Times Citation2020c) stated in a press briefing that the EP would not sidetrack CAI negotiations and the Global Times editors praised the impending agreement as a win-win breakthrough for global cooperation (Global Times Citation2020a).

Observing the emotional drivers behind the EU foreign policy and responses from third parties, it’s noticeable that, despite EU’s and especially the EP’s strong expressions of feelings of concern and indignation and emotions of outrage about human rights abuses in Xinjiang, the EP resolution did not lead to immediate action like suspending the CAI negotiations or imposing an EU ban on forced labour, creating a constraining mechanism which prevents further reactions. This constraining mechanism is thus reflected in an emotion-action gap where strong emotions do not translate into any action, aligning it with the research by Smith (Citation2021). Moreover, the emotional chains reveal that, even though the Chinese counterparts expressed anger over the EP’s and its members’ accusations of the Chinese government violating international norms, this wasn’t enough for China to react more severely than using its main mouthpiece to criticize the EP and its members. Thus, at this stage, a constraining mechanism which manifested itself in an emotion-action mismatch was exhibited on both the Chinese and European sides. Nevertheless, this entire spat was merely a preliminary clash, or a warning shot, foreshadowing what would come within the following three months.

In March 2021, utilizing its new sanctions regime to address global human rights violations, the Council of the European Union (Citation2021) imposed targeted sanctions on four Chinese individuals and an entity believed to be complicit in mistreating the Uyghur population in Xinjiang. It was the first time that the EU put its new ‘European Magnitsky Act’ into practice, acknowledging international norm violations. Apart from Chinese officials and entities, the EU levelled its sanctions against perpetrators from the DPRK (which we will discuss in the next section), Russia, Libya, South Sudan, Eritrea and, separately, Myanmar’s junta. The sanctions consisted of visa bans and asset freezes in the EU and prohibition from making any EU funds available, either directly or indirectly, to those listed.

In the case of China, EU ministers selected officials in Xinjiang alleged to be the architects of the large-scale surveillance, detention and indoctrination programme and a state-owned economic and paramilitary organisation considered to be in charge of the management of the detention centers in Xinjiang. Chen Quanguo, the Communist Party Secretary in Xinjiang and China’s Politburo member, seen as the top official in the region, was not blacklisted as much as none of the high-ranking officials in Beijing (Euronews Citation2021). The sanctions were therefore highly specific, targeting individuals immediately involved in implementing the human rights abuses rather than the decision-makers in Beijing.

Despite the EU’s endeavor to enact restrictive measures that would be carefully calibrated and were accompanied by a toned down text, China’s retaliation was much more expressive in its rhetoric and far-reaching in its scope. On the same day, Beijing designated ten individuals and four entities, including five members of the European Parliament (MEPs), such as Reinhard Bütikofer, the chair of China delegation and previously mocked Raphaël Glucksmann, the entirety of the EP’s Human Rights Subcommittee, the EU’s Political and Security Committee, or PSC (comprising 27 ambassadors from all EU member states), various members of national parliaments and several Swedish, Danish and German academics and think tanks.

The Chinese move not only substantially escalated diplomatic tensions but, crucially, introduced a powerful emotional element into the dynamic, exemplifying the emotions-driven chains of enabling mechanisms. Official statements from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and state-run media, such as the Global Times (GT), offer insights into China’s emotional stance influencing its decisions during this period. GT published a series of articles with harsh critiques in which it referenced ‘resolute, strong and just countermeasures’ (GT Citation2021d) and conveyed that sanctions were imposed on those ‘spreading rumors and deceitful narratives’ (GT Citation2021a) regarding Xinjiang, thereby ‘impairing China’s sovereignty and interests’ (GT Citation2021b) and warned that ‘individuals in EU countries who have behaved badly will not escape punishment’ (GT Citation2021e).

The angry and personalized undertone of the barrage of accusatory pieces was intense. German scholar, Adrian Zenz, was pinpointed as an ‘anti-China pseudo-researcher’ (GT Citation2021g), while Reinhard Bütikofer, chair of the EP’s China Delegation, was counseled to anticipate punitive measures (GT Citation2021f). Similarly, the EU’s actions were portrayed as exuding ‘moral arrogance’ (GT Citation2021b) and Cui Hongjian, a Director at the China Institute of International Studies, a research institute directly administered by the PRC’s foreign ministry, admonished the EU that it exploits human rights as its ‘most useful and advantageous weapon’ (GT Citation2021e). Cui further threatened, if ‘sanity remains in the EU’ (GT Citation2021c), to prevent human rights disputes from extending into the trade relationship, thereby insisting that ‘the EU will suffer much more pains, at a much higher cost if China makes a move’ (GT Citation2021e). Nonetheless, a spillover into trade sector is exactly what happened as we will see later.

China’s furious and overly retributory countermeasures altered the discourse and resulted in yet another institutional appraisal process in the EU. Even so, in stark contrast to China’s vehement backlash, European statements offered a more subdued depiction of EU relations with China. The Chair of the China Delegation Bütikofer, for instance, blamed the Chinese of no intention ‘to pursue any form of cooperation’ despite prior attempts to establish exchanges and contacts (European Parliament Citation2021a). Moreover, a joint statement (European Parliament Citation2021c) from leading MEPs (including the chairs of China delegation, foreign affairs, human rights and disinformation committees and subcommittees) and from the EP’s President Sassoli (together with the speakers of parliaments in Belgium, Netherlands and Lithuania) expressed solidarity with the sanctioned entities and individuals (European Parliament Citation2021d), underscoring a cohesive European stance against China’s retaliatory measures.

Notwithstanding the unclarity of who the actual persons under Beijing’s sanctions against the EP’s human rights subcommittee and the Council’s PSC are, China’s vitriolic and seemingly overreaching countermeasures may, paradoxically, have undermined its own political objectives. Even prior to Beijing’s excessive response, the CAI, already on precarious grounds due to concerns over forced labor in Xinjiang, has been plunged into further jeopardy. The sanctions against its own members made the EP decidedly unlikely to endorse the investment agreement. Consequently, during its May 2021 plenary session, the EP passed a resolution (European Parliament Citation2021b) with a massive majority of 599 out of 687 votes, suspending any vote on the CAI until Beijing lifts its sanctions.

This suspension showcased another emotionally charged episode in EU-China relations, with the EP resolution (European Parliament Citation2021b) condemning the Chinese measures as ‘baseless’, ‘entirely unsubstantiated and arbitrary’ and an ‘attack against the EU and its Parliament as a whole, the heart of European democracy and values’ and expressing that ‘intimidation attempts are futile’ and a ‘part of a totalitarian threat’ (European Parliament, Citation2021b). In addition to demands for lifting sanctions, the EP’s CAI resolution welcomes the EU human rights sanctions, invites other EU players to increase their cooperation on China with the US, review the EU’s China strategy and, finally, lists support for an investment agreement with Taiwan – all issues that are an anathema to Beijing.

Whether or not China’s leadership, including President Xi, fully grasped the intricacies of EU decision-making or the crucial role of the EP in approving the CAI and other China-related policies, they ought to have understood that agreements with Merkel (and Macron) do not automatically translate into agreements with the rest of Europe. Akin to TTIP, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (Morin et al. Citation2015), which did not proceed after President Trump took office, the CAI is now in a ‘freezer’, as phrased by a former EU trade Commissioner (Malmström Citation2017). A vital distinction exists, however, in that while the EU waited for the Biden administration to revive transatlantic trade discussions, a similar changeover is highly improbable anytime soon in Beijing. Ultimately, if President Xi intended to force the EU to ‘distance itself from Washington’s extreme policies to contain China’ (GT Citation2021b), the Chinese hostile overreaction may well have had the opposite effect.

Even though PRC has in the meantime proceeded to ratify several International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions on forced labour in April 2022 (ILO Citation2022) that could potentially apply to the situation in Xinjiang, only a newly elected members of the EP after the June 2024 elections may change the EP’s tune. Nonetheless, even that it is unlikely as Commission President von der Leyen indicated. In her speech about ‘de-risking’ from China from March 2023, she argued that the EU needs to reassess CAI in light of a wider China strategy (European Commission Citation2023) at an event that was emblematically co-organized by MERICS, one of the sanctioned think tanks. Likewise, considering the cultural importance of ‘saving one’s face’, it would be challenging for Beijing to de-escalate now from its side, too.

The trajectory of EU-China relations shows an interplay between emotions and (EU) foreign policy, where policy decisions are intricately tied to emotional responses, thereby highlighting a complex emotion-policy nexus. Beginning with optimism about enhanced trade cooperation, shifting through responses to human rights norm violations and culminating in emotionally charged tit-for-tat sanctions and countersanctions significantly impacted policy outcomes. illustrates the process of the intertwined nature between emotions and policy decision through a process of enabling and constraining mechanisms, with arrows pointing into one or the other direction to signify the two mechanisms. Understanding and managing such emotions is thus critical for navigating through and potentially resolving complex international dilemmas, particularly within the delicate context of EU-China relations. The next section will turn to our second case study – relations between the EU and North Korea, showing another example of how the emotions-policy nexus can play out.

Unfazed by sanctions: evaluating the emotional dimensions in the EU-North Korea relations

The prior discussion illuminated EU-China relations through a lens of complex chains of emotions, reactions and policy decisions influenced by both enabling and constraining mechanisms. Moving to our second case study involving the EU and North Korea/DPRK, it will be apparent that the emotions-policy nexus will reveal an alternative narrative, despite North Korea’s lesser prominence on the global stage. This section will delineate the emotional and policy chains that have transpired for nearly two decades since the EU first sanctioned the DPRK, with an examination of North Korea’s intertwined emotional and policy responses.

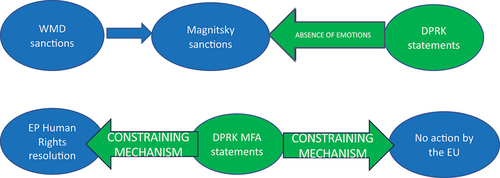

Different from its relationship with China, the EU initiated a robust sanctions regime against the DPRK in 2006, primarily to counteract its nuclear and ballistic missile programs. Broadly speaking, the EU sanctions on North Korea fall into three categories. The first entails the implementation of mandatory sanction regimes as dictated by the UN Security Council (UNSC), reflecting the UN members’ duty to enforce UNSC resolutions. The second includes the EU’s amplification of UNSC sanctions, a practice sometimes referred to as ‘gold-plating.’ The final strand involves the EU deciding its own autonomous restrictive measures without a UNSC mandate. below provides a summary of the EU’s security-related sanctions imposed on North Korea, distinguishing between those that implement the UN mandate (type: ‘UN’) and those that constitute its own autonomous restrictive measures (type: ‘EU’).

Table 1. Overview of EU sanctions against North Korea.

From the ,Footnote2 follows that the EU’s DPRK sanctions have been comprehensive, consisting of an arms embargo, restrictions on imports and exports of certain raw materials and goods, asset freezes, travel bans and additional economic and political pressures through bans on financial resources, luxury goods and overseas labour. Initially launched in 2006 as a response to North Korea’s first nuclear test and progressively intensified with successive nuclear and ballistic missile launches and program developments in 2013, 2016, 2017 and 2019 when the last nuclear test took place. Over the years, the sanctions’ scope was systematically expanded, incorporating both blanket bans and targeted measures against individuals and entities. In fact, until the Russian invasion of Ukraine shifted the focus to Moscow, the DPRK held the distinction of being the most sanctioned country by the EU globally (Novotná Citation2022b).

The accelerating EU sanctions are anchored in a blend of global security concerns and a principled opposition to nuclear proliferation. Under the label of its ‘critical engagement’ strategy, the EU has endeavored to not only curb the DPRK’s weapons programs but also coax Pyongyang into a dialogue and adherence to international norms, including human rights. Ballbach (Citation2022) identifies three logics behind EU sanctions on North Korea – coercion, constraining and signaling. However, the effectiveness of the EU’s critical engagement strategy, including its sanctions regime, aiming to simultaneously impede the DPRK’s military programs and encourage it to move towards diplomatic engagement, has been thoroughly assessed (Bondaz Citation2020; Ford Citation2018) and found persistently ineffectual both from the EU and international perspective.

While the EU’s North Korea sanctions are formulated in a factual, emotionless way, they are typically accompanied by statements from entities such as the EEAS Spokesperson, the High Representative (HRVP), or HRVP on behalf of the EU, and follow confrontational actions by the DPRK like missile launches, thus announcing them with a layered diplomatic weight (Fanoulis Citation2018). Nevertheless, even these statements often exhibit a pattern and carry minimal emotional load. For instance, a 2019 statement from the EEAS Spokesperson (EEAS Citation2019) denounced the DPRK’s ballistic missile launch, demanded restraint and urged a return to negotiations centered on the complete, verifiable and irreversible dismantlement (CVID) of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal.

Whereas the EU often asserts its demands toward the DPRK, the language utilized in its official statements tends to adhere to a consistent, or ‘agreed,’ wording. This uniformity in communication is evident in several of the EU’s statements, including potentially most potent discursive documents such as the ‘Declaration by HRVP on behalf of the EU on the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) Launch’ from March 2022 (Council of the EU Citation2022) and a statement by HRVP concerning an ICBM launch in July 2023 (Council of the EU Citation2023). Despite the latter being notably more detailed, it replicates portions of previous EU communications. Consequently, the DPRK’s reactions (when they do occur at all) unsurprisingly mirror this repetitive communication style. For instance, a press statement issued by an Adviser from the Korea-Europe Association on 29 August 2019 (KCNA Citation2019/Juche 108) exemplifies North Korea’s typical response which entails condemning the EU and its member states for interference in its domestic affairs and asserting its right to self-defense.

In sum, the repetitive emotion-less nature of the EU’s declarations, coupled with the DPRK’s consistent breaches of all sanction regimes and the perceived lack of the EU’s importance as an actor on the Korean peninsula, has failed to generate a chain of emotional responses. In essence, North Korea typically exhibits a standard reaction of absence of emotions.

Given that all the previously mentioned sanctions and statements are related to Pyongyang’s nuclear and WMD activities, is there a different approach when addressing human rights issues? As discussed earlier in this article, in March 2021, the EU employed the same global human rights sanctions against North Korea, similar to those applied to China, targeting two individuals and one entity, i.e. ministers of state police and secret police and the office of the DPRK’s prosecutor. While these ‘European Magnitsky sanctions’ symbolically targeted mid-level figures without directly implicating the Kim family (Zwirko Citation2021), North Korea’s response contrasted sharply with China’s, illustrating varying emotional chains and policy reactions.

Pyongyang, while issuing a statement lambasting the EU’s actions, did not counteract with its own sanctions or similar policies, revealing a discernible constraining mechanism, or emotion-action gap, in the relationship. In a manner akin to Beijing, however, Pyongyang utilized vivid language to convey its indignation, employing terms somewhat parallel to those used by outlets such as the Global Times. A spokesperson from the DPRK’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (KCNA Citation2021/Juche 110) called the EU Magnitsky sanctions a ‘farce’ and a ‘futile act [that] will incur only disgrace and shame,’ describing it as ‘an evil legislation contrived to put pressure on those countries that do not kowtow to EU,’ which was portrayed as a puppet of the United States.

The spokesperson ultimately issued a caution, stating, ‘EU needs to bear in mind that if it persistently clings to the futile anti-DPRK “human rights” smear campaign in disregard of our repeated warnings, it will inevitably be faced with unimaginable and miserable consequence’, leaving the nature of these ‘unimaginable and miserable consequences’ unspecified. Following North Korea’s eloquent yet in effect lackluster response, the EU did not take any further immediate action either. A year and a half later, in December 2022, the EU extended its human rights sanctions regime against North Korean offenders for a second consecutive year (Bremer Citation2022a) without designating any new wrongdoers. On this occasion, Pyongyang’s response was distinctively muted – it opted not to respond at all, displaying yet again an absence of emotions.

To control for the objective of sanctions – human rights violations vs security developments – as well as for the involvement of the European Parliament as a separate EU institution, the EP’s resolution of 7 April 2022 concerning human rights in North Korea, especially pertaining to the persecution of religious minorities, warrants scrutiny. Despite the commendable focus of the resolution, its foundation on an NGO report of questionable veracity including alleged executions of priests raised concerns (Bremer Citation2022b).

While it’s undisputed that religious groups in North Korea undergo severe persecution, the DPRK’s foreign ministry (KCNA Citation2022/Juche 110) issued a vehement rebuttal, labeling the EP ‘a gang of liars concocting falsehoods’ and declaring the resolution’s adoption ‘an intolerable provocation and an act of hostility scheming to tarnish the dignified image of our Republic.’ However, unlike in the EU-China situation, the DPRK government refrained from taking any additional factual steps, showcasing a kind of restrained anger and exposing a constraining mechanism and emotion-action gap. This instance once again presents a scenario where a limited chain of emotional and reactive interactions occurred. illustrates the EU-North Korea relations in which norm violations do not precipitate a moment that would fuel further emotional responses, instead revealing a constraining mechanism and/or absence of emotions.

Concluding reflections: comparative insights and implications for policy makers

Our investigation into the interlinked realms of emotions and (EU) foreign policy, specifically through the lens of the EU sanctions related to human rights violations, unveils a composite structure of theoretical and practical considerations. This concluding discussion seeks to weave through the intricate threads of the emotional underpinnings of foreign policy decisions, examining these dynamics in two distinct geopolitical contexts, i.e. EU-China and EU-North Korea/DPRK relations. While comparing and contrasting the two case studies, the concluding section attempts to encapsulate the overarching narrative that emerges from these multifaceted analyses and distills them into coherent policy-oriented insights.

In its second section, this article outlined the extended framework of analysis which intrinsically links emotions and policy into multistep chains, recognizing the cruciality of emotions in influencing, directing and, at times, constraining policy decisions. The extended framework attempts to visualize a deeper understanding of the EU’s foreign policy, incorporating the emotional responses and policy actions particularly related to sanctions imposed concerning human rights issues.

Navigating through the extended framework of analysis that captures the nexus between emotions and policy decisions, it is essential to emphasize that emotions both influence and are influenced by policy actions or non-actions in a two-way street manner. Emotions are not merely reactionary but are constitutive of the political landscapes within which policies are formulated and enacted. Thus, emotions, in this context, are wielded and experienced by national governments and entities such as the EU, transcending beyond individual affective responses and emerging as collective emotional expressions.

Human rights sanctions, often embedded with value and ethical judgments, naturally engender emotional responses from both imposing and recipient entities, thereby initiating a chain of emotionally-charged interactions. Emotionally-infused human rights sanctions not only communicate moral standings but also become mediums through which identities and values are expressed and contested.

The third section of this article examined the EU-China relationship as encompassing various domains, such as trade and human rights. Particularly under the impact of the US-China rivalry, human rights have become an increasingly significant point of contention and emotional dispute between the EU and China. The imposition of human rights sanctions by the EU in March 2021, based on reports of international norm violations in Xinjiang, demonstrates an overt emotional response by the EU to reported injustices. Here, emotions such as empathy towards affected individuals and moral outrage towards the Chinese government were evident.

In a reciprocal manner, Beijing, too, unleashed its emotional policy responses. These emotions were manifest in Chinese diplomatic and media statements that conveyed anger, disdain and threats, reflecting not only an emotional response to the imposition of sanctions but also a calculated expression meant to convey Beijing’s political sentiments. Subsequently, China imposed retaliatory measures against the EU, reflecting an evident policy impact resulting from these emotional responses. Here, emotions provided the substance that influenced and justified policy responses, serving as both a mediator and a communicator of underlying principles and policy positions. The EU-China bilateral relationship thus became trapped in a complex cycle where policy decisions and emotional responses became reciprocally influential, thereby signaling a nexus where emotions played an enabling and constraining role in determining policy directions.

Contrastingly, as explored in the fourth section of this article, the EU-North Korea/DPRK dynamic offers a different portrait of emotions-policy nexus. The EU, adhering to its critical engagement policy and also aligning itself with UN mandate, has for a long time maintained a strict sanctions regime against the DPRK primarily due to its nuclear proliferation activities. Human rights violations that came only later as justification for EU’s new sanctions evoked emotions of moral indignation and empathy from the EU, but did not substantially alter the EU’s already stringent policy stance against the DPRK.

Interestingly, the DPRK’s responses have been uniquely divergent from that of China. Emotional expressions from the DPRK, often conveyed through vocal, colourful rhetoric, manifested emotions of defiance, condescension and perhaps a concealed sense of vulnerability. However, these emotional expressions were not directly translatable to immediate policy alterations. Despite vehement objections and emotive declarations, the DPRK has consistently sustained its strategic pathways, indicating a potential decoupling or differential application of emotions within its policy-making calculus. In essence, possibly due to Pyongyang’s accustomed designation as the international community’s pariah and its disregard for the EU’s role in NE Asia, regardless of the underlying rationale, it did not view the EU’s human rights sanctions as a deviation from the norm, nor deemed it worthy of a specific response.

Comparing the EU’s relationships with China and the DPRK brings into stark contrast the variances in how emotions-policy nexus can unfold within different international contexts. Particularly under the umbrella of the US-China competition, the reciprocal policy and emotional responses between the EU and China exhibit a more directly relational approach where emotional responses and policy decisions are deeply intertwined and reflective. In contrast, the EU-DPRK dynamic exhibits a more unidirectional emotional impact where North Korea’s emotional expressions and policy reactions do not match. Such contrasting cases underscore the fluidity of emotions-policy chains and spotlight the necessity to contextualize emotional analyses within specific bilateral relationships and geopolitical contexts.

In synthesizing insights from both case studies, it is evident that emotions cannot be extricated from policy reactions and that the emotions-policy nexus can yield varied chains of emotional reactions contingent upon the entities involved. The impact of sanctions, particularly those anchored in human rights concerns, extends beyond directly-linked economic or geopolitical spheres, permeating and influencing the subsequent policy deliberations and directions. Future research may delve deeper into deciphering the subtle and overt roles emotions play within varied international contexts, thereby enriching the analytical frameworks through which we understand, navigate and predict international relations and foreign policy.

If we step further into the policy-making sphere, embracing the understanding that emotions permeate political decision-making, especially in the context of sanctions, may present practitioners with a complex, albeit enriching, palette of considerations. The emotions-policy nexus showcased through the EU’s relations with China and the DPRK highlights that the impact of sanctions is intrinsically tied to the emotional narratives and counter-narratives that they construct. Based on the two case studies, these findings raise pertinent questions regarding the types of sanctions and their effectiveness imposed not only by the EU but also by UN and other international actors, though a thorough debate on this matter would warrant a dedicated article.

All in all, it is imperative for policymakers, in Europe or elsewhere, to conscientiously engage with the emotional dimensions embedded within sanctions, and foreign policy more broadly, recognizing that emotions communicate, provoke and reshape policy outcomes. Navigating through various emotional chains can potentially enhance the efficacy and resonance of sanctions and other types of foreign policies, aligning them more congruently with intended objectives and mitigating unintended or counterproductive emotional and policy reactions, or non-reactions. Whether or not policymakers are aware of the vital role that emotions play in (EU) foreign policy-making remains to be seen in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. For the activities of the German EU Presidency, including social media, see https://www.eu2020.de/.

2. In the , the ‘UN’ type designates EU sanctions that transpose UNSC-mandated sanctions; the ‘EU’ type designates the EU’s autonomous restrictive measures. On 12 December 2016, the Council of the EU released its conclusions related to the DPRK’s nuclear test rather than sanctions. The table has been created based on the data available on the Council of the EU website: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/history-north-korea/. Compiled by the author.

References

- Ballbach, E. J. 2022. “Moving Beyond Targeted Sanctions: The Sanctions Regime of the European Union Against North Korea.” SWP Research Paper 2022/RP 04, Accessed February 18, 2022. https://doi.org/10.18449/2022RP04.

- Bondaz, A. 2020. ‘From Critical Engagement to Credible Commitments: A Renewed EU Strategy for the North Korean Proliferation Crisis, EU Non-Proliferation and Disarmament.’ Consortium, Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Papers, No. 67 (February 2020).

- Bremer, I. 2022a. “European Council Renews Human Rights Sanctions on Top North Korean Officials.” NK News. December 6. https://www.nknews.org/2022/12/european-council-renews-human-rights-sanctions-on-top-north-korean-officials/?t=1696804482.

- Bremer, I. 2022b. “North Korea Slams European Parliament As ‘Gang of liars’ After Human Rights Vote.” NK News, April 20. https://www.nknews.org/2022/04/north-korea-slams-european-parliament-as-gang-of-liars-after-human-rights-vote/.

- Clément, M., and E. Sangar. 2018. Researching Emotions in International Relations: Methodological Perspectives on the Emotional Turn. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Council of the European Union. 2020. “Council Decision (CFSP) 2020/1999 of 7 December 2020 Concerning Restrictive Measures Against Serious Human Rights Violations and Abuses.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2020:410I:TOC.

- Council of the European Union. 2021. “Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/478 of 22 March 2021 Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1998 Concerning Restrictive Measures Against Serious Human Rights Violations and Abuses.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2021:099I:FULL&from=EN.

- Council of the European Union. 2022. “Declaration by the High Representative on Behalf of the EU on the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM).” launch https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/03/25/dprk-declaration-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-eu-on-the-intercontinental-ballistic-missile-icbm-launch/.

- Council of the European Union. 2023. “Statement by the High Representative on Behalf of the European Union on the Launch of an Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile.” July 14. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/07/14/north-korea-dprk-statement-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-european-union-on-the-launch-of-an-inter-continental-ballistic-missile/.

- Council of the European Union. 2024. “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Prohibiting Products Made with Forced Labour on the Union Market - Mandate for Negotiations with the European Parliament.” January 26. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5903-2024-INIT/en/pdf.

- EEAS. 2019. “Statement by the Spokesperson on the Latest Provocation by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.” October 2. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/statement-spokesperson-latest-provocation-democratic-people’s-republic-korea_en.

- Ellena, S. 2023. “EU Lawmakers Seek More Ambitious Ban on Forced Labour Products.” Euractiv. July 19, 2023. https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/eu-lawmakers-seek-more-ambitious-ban-on-forced-labour-products/.

- Euronews. 2021. “EU Agrees First Sanctions on China in More Than 30 Years.” Euronews. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2021/03/22/eu-foreign-ministers-to-discuss-sanctions-on-china-and-myanmar.

- European Commission. 2023. “Speech by President von der Leyen on EU-China Relations to the Mercator Institute for China Studies and the European Policy Centre.” March 30. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_2063.

- European Commission, and EEAS. 2019. “EU-China – a Strategic Outlook.” Accessed April 30, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2020. “European Parliament Resolution of 17 December 2020 on Forced Labour and the Situation of the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (2020/2913(RSP)).” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0375_EN.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2021a. “Chair’s Statement of 23 March 2021 on EU Sanctions on Human Rights Violations.” Counter-sanctions by the PRC. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/delegations/en/d-cn/documents/communiques.

- European Parliament. 2021b. “Chinese Countersanctions on EU Entities and MEPs and MPs.” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0255_EN.html.

- European Parliament. 2021c. “Joint Statement of 23 March 2021 on Human Rights Abuses in China.” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20210323IPR00601/meps-continue-to-firmly-condemn-human-rights-abuses-in-china.

- European Parliament. 2021d. “Joint Statement of 29 March 2021 on Chinese Sanctions Against Members of Parliaments.” https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/233366/03_31_D(2021)06031_Annex%20-%20Joint%20Declaration.pdf.

- Fanoulis, E. 2018. “The EU’s Democratization Discourse and Questions of European Identification.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56:1362–1375. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12747.

- Ford, G. 2018. Talking to North Korea: Ending the Nuclear Standoff. London: Pluto Press.

- Friedlander, J. 2020. “Furor Over Europe’s Investment Agreement with China Is Overblown.” Accessed April 30, 2021. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/furor-over-europe’s-investment-agreement-china-overblown-175397.

- Global Times. 2020a. “China-EU Investment Treaty Breakthrough Win-Win for Global Cooperation.” Global Times editorial. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1210391.shtml.

- Global Times. 2020b. “EU Parliament Needs Return to Common Sense on China: Global Times Editorial.” Global Times editorial. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1210348.shtml.

- Global Times. 2020c. “FM Refutes Report on EU-China CAI; Steady Bilateral Relations Benefit World.” Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1210654.shtml.

- Global Times. 2021a. “China Hits Back at EU Sanctions Over Xinjiang Affairs, Sending Strong Signal Urging Foreign Countries to Stop Meddling in Its Internal Affairs.” https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219138.shtml.

- Global Times. 2021b. “China’s Sanctions Over EU Officials and Entities Are Justified and Timely: Global Times Editorial.” https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219143.shtml.

- Global Times. 2021c. “EU ‘Insane’ to Extend Conflict to Economic Field: Observers.” https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219240.shtml.

- Global Times. 2021d. “Exclusive: China Formulating Countermeasures Against Planned EU Sanctions Over Xinjiang; No Escape for Some EU Institutions and Poorly Behaving Individuals.” https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1218882.shtml.

- Global Times. 2021e. “High-Profile Individuals, Including European Parliament Officials, Are Likely to Be Included in China’s Countermeasures; Legal Procedures to Follow, Warned Experts.” https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219069.shtml.

- Global Times. 2021f. “No. 1 on China’s Sanction List, MEP Reinhard Bütikofer, Should Have Been Sanctioned Earlier: Senior Expert.” https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219146.shtml.

- Global Times. 2021g. “Who Are Those on China’s Sanctions List Against EU, and Why These Sanctions Are Justified?” https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219259.shtml.

- Gürkan, S., and R.Coman. (2021). “The EU–Turkey deal in the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’: when intergovernmentalism cast a shadow on the EU’s normative power.“ Acta Polit 56 (2): 276–305. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00184-2.

- Gürkan, S., and O. Terzi. 2024. “Emotions in EU Foreign Policy – When and How Do They Matter?.” Journal of European Integration 5 (46).

- ILO. 2022. “ILO Welcomes China’s Move Towards the Ratification of Two Forced Labour Conventions.” International Labour Organization. April 2022. https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_842739/lang–en/index.htm.

- KCNA /Juche 108. 2019. “Press Statement Issued by Adviser from Korea-Europe Association.” August 29. http://www.kcna.kp/en/article/q/59b4eb9b3cc6925359ade3537d043ec8ec6e0f0df639b9dbdae7112f0217dca7.kcmsf.

- KCNA Juche 110. 2021. “Futile Act Will Incur Only Disgrace and Shame: Spokesperson for DPRK Foreign Ministry.” March 23. http://www.kcna.kp/en/article/q/59b4eb9b3cc6925359ade3537d043ec88cbd782387e28313b642b0d2a9ab8494.kcmsf.

- KCNA Juche 111. 2022. “Gang of Liars Concocting Falsehood.” April 19. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1650360718-734750978/gang-of-liars-concocting-falsehood/.

- Koschut, S., ed. 2020. The Power of Emotions in World Politics. London and New York: Routledge.

- Malmström, C. 2017. Safeguarding Common Values in the Age of Globalisation: Speech by Cecilia Malmström. EEAS: European Commissioner for Trade UNAM University. Accessed May 24, 2024. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/25813en.

- Manners, I. 2021. “Political Psychology of Emotion(al) Norms in European Union Foreign Policy.” Global Affairs 7 (2): 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2021.1972819.

- Morin, J. F., T. Novotná, F. Ponjaert, and M. Telò, eds. 2015. The Politics of Transatlantic Trade Negotiations: TTIP in a Globalized World. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Novotná, T. 2022a. “From Connectivity to Sanctions and from Soft to Hard Power Approaches: How the European Union and South Korea Have Been Responding to the US- China Competition.” In Korea, the Iron Silk Road and the Belt and Road Initiative Soft Power and Hard Power Approaches, edited by B. Seliger and R. Wrobel, 185–201. Berlin: Peter Lang.

- Novotná, T. 2022b. “What North Korea Has Been Learning from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine.” East-West Center. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.eastwestcenter.org/publications/what-north-korea-has-been-learning-russias-invasion-ukraine.

- Novotná, T., and A. Ford. 2019. “Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un Need the European Union.” The Bulletin. Accessed 3 May 2019. https://thebulletin.org/2019/05/donald-trump-and-kim-jong-un-need-the-european-union/.

- Onderco, M. 2024. “Why Sanctioning? Rise and Purpose of Sanctions in International Politics.” In Punishment in International Society: Norms, Justice, and Punitive Practices, edited by W. Wagner, 142–159. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pace, M., and A. Bilgic. 2018. “Trauma, Emotions, and Memory in World Politics: The Case of the European Union’s Foreign Policy in the Middle East Conflict.” Political Psychology 39 (3): 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12459.

- Sanchez Salgado, R. 2021a. “Emotions in European Parliamentary Debates: Passionate Speakers or Unemotional Gentlemen?” Comparative European Politics 19 (4): 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-021-00244-7.

- Sanchez Salgado, R. 2021b. “Emotions in the European Union’s Decision-Making: The Reform of the Dublin System in the Context of the Refugee Crisis.” The European Journal of Social Science Research 35 (1): 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2021.1968355.

- S&D Group. 2020. “S&Ds Call for Human Rights Sanctions and EU Ban on Products Made with Uyghur Forced Labour.” S&D Group Press Release. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://mailchi.mp/socialistsanddemocrats/sds-call-for-human-rights-sanctions-and-eu-ban-on-products-made-with-uyghur-forced-labour-762534?e=6483f6871a.

- Smith, K. 2021. “Emotions and EU Foreign Policy.” International Affairs 97 (2): 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa218.

- Telò, M. 2021. “Controversial Developments of EU–China Relations: Main Drivers and Geopolitical Implications of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investments.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (S1): 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13226.

- Terzi, Ö., Trineke Palm, and Seda Gürkan. 2021. “Introduction: Emotion(al) Norms in European Foreign Policy.” Global Affairs 7 (2): 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2021.1953394.

- van Rythoven, E., and T. Solomon. 2020. “Encounters Between Affect and Emotion: Studying Order and Disorder in International Politics.” In Methodology and Emotion in International Relations: Parsing the Passions, edited by E. Van Rythoven and M. Sucharov, 133–151. London and New York: Routledge.

- Zwirko, C. 2021. “EU Hits North Korea with Human-Rights Related Sanctions for the First Time.” NK News. https://www.nknews.org/2021/03/eu-hits-north-korea-with-human-rights-related-sanctions-for-the-first-time/.