ABSTRACT

The ninth-century poet and musician, Ziryab, is synonymous with the musical cultures of Muslim Spain (al-Andalus) and the idea of commonality between different genres across the Mediterranean. While some scholars have deconstructed the myth of Ziryab at a historiographical level, there has been less consideration of how the myth is interpreted in contemporary musical practice. This article examines how Ziryab is reinterpreted in the present through intercultural music making. Drawing on fieldwork in Madrid and Valencia (2016), I focus on the Ziryab and Us: A New Vision of the Arab-Andalusian Heritage project, in which French, Israeli, Moroccan and Spanish musicians sought to reinterpret the legend of Ziryab through the lens of their own musical traditions. I argue that Ziryab functioned as a discursive trope that engendered a series of micro-social relations between the musicians, framed by ideas of musical affinity, a shared cultural space (the Mediterranean) and cross-cultural exchange. But beyond the ideals of musical connection that Ziryab implies, the relational processes that characterised the project were not always unified. Therefore, I examine some of the points of tension that emerged when the musicians brought together distinct traditions under the rubric of a shared ‘Andalusian’ or Mediterranean heritage.

Ziryab was a medieval musician and poet (c. 789–857) who has become synonymous with the musical cultures of Muslim Spain (al-Andalus, 711–1492). According to legend, Ziryab was responsible for various musical innovations such as founding the first conservatoire in Córdoba, the creation of Arab-Andalusian musical styles, the development of music theory, advancements in oud design, as well as innovations in fashion and social etiquette. This larger-than-life figure is often incorporated into the historical narratives of musical traditions that can supposedly trace their roots to al-Andalus. While some scholars have sought to deconstruct the myth of Ziryab at a historiographical level (Davila Citation2013; Reynolds Citation2008; Shannon Citation2015: 38–40), there has been less consideration of how the myth is interpreted in contemporary musical practice. Jonathan Shannon (Citation2015: 40) describes Ziryab as a discursive trope in which people ‘hear their own cultural roots and heritage’, but a trope that also informs the idea of musical commonalities across the Mediterranean. In this article, I examine how Ziryab is reinterpreted in the present through intercultural music making, focusing on the project Ziryab and Us: A New Vision of the Arab-Andalusian Heritage. Comprised of French, Israeli, Moroccan and Spanish musicians, the project sought to reinterpret the legend of Ziryab through the lens of the musicians’ own traditions. I argue that Ziryab functioned as a discursive device that put into motion a series of micro-social relations between musicians, framed by ideas of musical affinity, a shared cultural space (the Mediterranean) and intercultural dialogue. But beyond the ideals of musical connection that Ziryab implies, the relational processes that characterised the project were not always unified. I examine the points of tension (artistic, interpersonal and political) that emerged when the musicians brought together distinct traditions under the rubric of a shared ‘Andalusian’ and Mediterranean heritage.

The Ziryab and Us project emerged from the Medinea (Mediterranean Incubator of Emerging Artists) network, a group of cultural organisations funded through the European Union that supports musical collaboration across the Mediterranean.Footnote1 Drawn from artistic residencies in 2015 and 2016 at the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, a group of talented young musicians formed a collaborative project with the goal being to ‘revisit the Ziryab legend through the cultural and aesthetic frameworks of the artists’ different musical backgrounds. Through intense intercultural exchange, the artists challenge the boundaries of their traditions and their own individual musical identities and aesthetics’ (Ziryab and Us Citation2016). Ziryab and Us was organised and managed by Virginia Pisano (development manager of the Medinea network) and consisted of the following musicians (): the Moroccan Arab-Andalusian singer Abir El Abed; Yoav Eshed, an Israeli jazz guitarist; Colin Heller, a French classical violinist and folk musician; the Spanish flamenco flautist Sergio de Lope; and Sergio Martínez, a Spanish flamenco percussionist. I attended a week-long residency with the group in May 2016, which took place at the Berklee College of Music in Valencia followed by a concert at Casa Árabe in Madrid. During this time, I observed and filmed the rehearsals and group conversations, and socialised with the musicians outside of rehearsals. As a result, I was able to observe in detail the decision-making processes and negotiations between the musicians as the project developed.Footnote2

Figure 1. Photo of the Ziryab and Us musicians. From left to right the musicians are: Sergio Martínez, Yoav Eshed, Abir El Abed, Colin Heller and Sergio de Lope. Photo by the author, Valencia, 6 May 2016.

This article is inspired by recent work in ethnomusicology that focuses on the micro-social relations that characterise intercultural music projects (Balosso-Bardin Citation2018; Bayley and Dutiro Citation2016; Brinner Citation2009; Cook Citation2012; Goldstein Citation2017). I am interested in how the musicians in Ziryab and Us brought into dialogue diverse musical systems, framed by the discursive trope of Ziryab and musical commonality across the Mediterranean. However, by focusing too heavily on the micro-social relations that characterise collaborative projects, it is easy to miss some of the broader institutional, historical and political issues that influenced the creative process. Nicholas Cook (Citation2012) describes the musical encounters of two or more cultural traditions as ‘situated’ encounters. He argues that such encounters should be framed by the wider social, ideological and historical contexts in which they take place. For Cook, these encounters involve negotiating the space between two (or more) situated cultural traditions/worldviews in ‘an attempt to bring two quite different conceptions into line with one another’ (Cook Citation2012: 203).

In balancing the micro and macro relations that underpinned Ziryab and Us, this article also interrogates the project through the theoretical framework of intercultural dialogue (ICD). Ted Cantle understands ICD as ‘a practice or a process that is instrumental to implementing the aims of interculturalism, such as fostering understanding and empathy with others’ (cited in Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2020: 11; Cantle Citation2012). It is worth here disentangling interculturalism and ICD. The former might be understood as a philosophy or political strategy that aims to develop mutual understanding between different cultural communities, based on dialogue, exchange and the fostering of shared cultural values (Cantle Citation2012).Footnote3 The latter can be understood as the process by which interculturalism as a strategy is realised – a mode of engagement through which different cultural traditions come into contact in search of something ‘new’. ICD, as a mode of creative engagement for implementing the ideals of interculturalism often forms the basis for various cultural projects across the European Union that facilitate cross-border and intercultural exchange between countries that straddle the external borders of Europe of which Medinea is one example. Very often such projects of ICD are presented as apolitical, even if their underpinnings are guided by the national and supranational politics of diversity and community cohesion.

In the musical context, Bayley and Dutiro (Citation2016: 391) argue that ‘Intercultural music-making can be understood by studying the way ideas are communicated between musicians, how roles and responsibilities are defined and how a middleground is negotiated’. I am particularly interested in the ‘middleground’: dialogic moments, the ‘interspace’ between cultures and what new cultural forms emerge from intercultural encounters, as well as what points of tension emerge. To understand the objectives and outcomes of Ziryab and Us, I analyse both the micro-scale creative processes that took place in the rehearsals and the macro-scale cultural, historical and institutional factors that underpinned the project. Here, I focus on three sets of relational processes. First, I examine the individual musicians’ relationships with their own traditions and how those relationships were influenced by the collaborative process. I then trace the group’s search for a common musical language, and the tensions that emerged between Ziryab as a metaphor for musical commonality and the bridging of distinct musical styles. Finally, I consider the influence of institutional contexts, wider discursive strategies (such as Mediterraneanism) and political/religious issues (Spanish-Moroccan (post)colonial relations and Israeli-Arab tensions) that nuanced the collaborative process.

Unpacking the Myth of Ziryab

He is said to have memorized the lyrics and melodies of ten thousand songs and to have composed innumerable songs of his own […]. He is also said to have developed new techniques for teaching the art of singing and to have added a fifth string to the Arab lute. In short, he is frequently attributed with having single-handedly crafted a style and repertory that became the foundation for all Andalusian music from the ninth century to the present. It is not uncommon for modern musicians even today, particularly in North Africa, to claim that their music is descended directly from the music and performance practices of Ziryab. (Reynolds Citation2008: 155)

Few written sources survive regarding Ziryab and those that do are largely anecdotal. Dwight Reynolds (Citation2008) and Carl Davila (Citation2013) have both thoroughly deconstructed the historiography surrounding Ziryab. As Reynolds argues, practically everything we know about the figure comes from an account by the seventeenth-century writer Shih ab al-Din Ahmad al-Maqqarī whose larger-than-life depiction of Ziryab has fed into present-day mythology. Interestingly, as Reynolds shows, a lot of the detail in al-Maqqarī’s account is actually drawn from an eleventh-century text by Ibn Hayyān, and Hayyān himself drew on an earlier anonymous text called Kitāb Akhbār Ziryāb. It is this account of Ziryab’s life that Carl Davila (Citation2013: 80–116) claims is most historically accurate, given its emphasis on court patronage for the arts at the time and its multivocal portrayals of Ziryab’s personal life. Reynolds (Citation2008: 166) argues that in al-Maqqarī’s interpretation of Ibn Hayyān’s account he ‘selected and suppressed materials […] in such a systematic ̇way that it is difficult not to see his redaction as a purposeful and conscious effort to transform Ziryab into a figure of mythic proportions’.

Today, the figure of Ziryab appears in a number of musical and non-musical settings, retaining much of the mythical status that was constructed by al-Maqqarī. What is most striking is the extent to which musicians see Ziryab as historical fact, but more than that, he is seen as a connecting bridge between genres across the Mediterranean. Indeed, the notion that the diverse musical traditions of North Africa, the Levant and Spain can be put under a single umbrella of so-called Andalusian music rests predominantly on the idea that they can all be traced back to Ziryab (Shannon Citation2015: 37). This is perhaps most prevalent in the context of flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music (particularly the al-âla tradition from Morocco), two traditions that many musicians argue have their roots in the cultural history and intermixing of different ethnicities and religions in Muslim-ruled Spain.

It is the notion of musical connection across the Mediterranean that lies at the heart of the Ziryab and Us project. When I first met Virginia Pisano, I asked her why she chose the title. While admitting that she needed to choose a title quickly, she nonetheless emphasised the popularity of the Ziryab legend and its relevance for the idea of a shared musical heritage across the Mediterranean and specifically between Spain and Morocco (personal communication, Valencia, 1 May 2016). Lähdesmäki et al. (Citation2020: 12) argue that ‘One of the societal prerequisites commonly emphasized as key for intercultural dialogue is a “shared space”’, such as a physical or virtual environment. At one level, the institutional setting of Berklee and the underpinning EU framework of Medinea provided the physical and infrastructural space for the Ziryab and Us project. However, at a more metaphorical level, one might interpret Ziryab himself as a shared space for the enactment of ICD, a space of myth building. Ziryab, I argue, functioned in the project as a discursive ‘anchor’, a metaphor for a broader discourse of cultural commonality and exchange around the Mediterranean.

The Musicians’ Relationship with Tradition

In 2014, Virginia Pisano started to work for the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence as development manager for the newly founded Medinea network. The Festival had traditionally focused on classical music and opera, but the creation of the Medinea network expanded the Festival’s connections with Mediterranean musical organisations and the inclusion of musical traditions representative of the region. Virginia was in charge of selecting young, talented musicians from across the Mediterranean and facilitating the creation of intercultural collaborations of which Ziryab and Us was one such project. Colin, Abir and Yoav had previously collaborated at residencies hosted by the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, with Sergio de Lope and Sergio Martínez joining at a small workshop held in February 2016. Therefore, when the musicians arrived in Valencia, some of the material had already been worked on at previous meetings and the musicians shared recordings in the run up to the residency. The musicians’ challenge was to create a programme for the concert in Madrid combining their diverse musical backgrounds under the rubric of Ziryab and the Arab-Andalusian musical legacy. As mentioned above, it was Virginia who chose the Ziryab and Us title and in many respects the whole concept for the project was her brainchild. However, the musicians still had significant artistic control, and during the rehearsals Virginia mostly took a back seat allowing the musicians to interpret the ‘brief’ and facilitate the rehearsals as they saw fit. For most of the musicians, this was the first time they had worked in such an explicitly intercultural setting crossing a range of genres. Therefore, alongside the chance to record with the well-known world music producer Javier Limón and a paid concert in Madrid, the residency was also an opportunity for the musicians to expand their musical horizons.

As Amanda Bayley and Chartwell Dutiro (Citation2016: 391) argue: ‘Understanding the processes involved in intercultural music-making requires exploring the space between cultures, as defined by the prefix “inter”. This space takes a different shape for each collaboration because it is determined by the individuals involved as much as by the cultures themselves’. In the following two sections, I examine the cultural (and political) dimensions of the musicians’ search for a ‘common musical language’ through the dialogue of disjunct, but discursively connected, traditions. But as Bayley and Dutiro indicate, intercultural music making is also highly dependent on the role of the individual musicians. In this section, therefore, I examine how the project nuanced the relationship between the musicians and their specific musical traditions. Virginia told me that she was inspired by the mythologising of Ziryab as a ‘musical hero’ and she wanted to personalise the myth in the project, hence the use of the object pronoun ‘us’. Ultimately, she encouraged the musicians to reconsider their own relationship with their musical traditions through intercultural collaboration. Here, the project instigated an interesting tension: it provided a seemingly neutral artistic space, free of aesthetic and stylistic constraints, in which the musicians could expand their creative horizons (at least within the predetermined framework provided by the trope of Ziryab). However, the musicians often became de facto representatives of their traditions and sometimes retreated to their comfort zones and familiar musical competencies (Stobart Citation2013).

The balance of tradition and engagement with unfamiliar styles was not easy for the musicians: Abir El Abed is a good example. Abir trained for ten years at a music conservatoire in Tangier where she received a classical training in the Moroccan Arab-Andalusian tradition of al-âla. While still only in her twenties, she has developed a prominent reputation as one of the leading voices of the tradition in Morocco, a significant achievement for a young woman in a largely male-dominated musical domain. While she has experimented with flamenco before, she told me that Ziryab and Us was the first time she had taken part in such a large-scale Mediterranean collaborative project. Indeed, she told me ‘I would never be able to do these sorts of fusions in Morocco, I would lose respect’ (personal communication, Valencia, 2 May 2016). As a young woman with relatively frequent coverage in the Moroccan media, she felt caught between the negative judgment of classical Arab-Andalusian conservatoire musicians due to her innovations and the expectations of younger Moroccans who encourage her to branch out into other, more popular, musical domains.

This sense of straddling two worlds was evident in how she approached the Ziryab and Us project. Although her very involvement was by default breaking the mould of traditional Arab-Andalusian music, her felt need to maintain tangible links with classical practice sometimes held back her ability to experiment in the residency. For example, on one occasion she volunteered to lead a rehearsal as the group leader, Sergio Martínez,Footnote6 was absent from the session and the musicians were working on a piece from the classical Arab-Andalusian repertoire that she had introduced to the group. As the group sought to construct their own arrangement that suited the musicians’ diverse musical competencies, Abir tried to restrict the arrangement according to a more classically Arab-Andalusian aesthetic in terms of orchestration and melodic accompaniment. At one point during the rehearsals when the musicians were struggling to settle on a unified direction that melded together their different backgrounds, Virginia decided to intervene asking them: ‘Do you prefer to put yourself in an uncomfortable situation that is less safe, but probably more interesting? Or do you prefer to play it safe?’ (group conversation, Valencia, 4 May 2016). While this comment was directed at the whole group, it was Abir in particular who tended to ‘play it safe’. Virginia encouraged the musicians to ‘leave behind and forget a part of themselves in order to work towards an innovative, collaborative project’ (Valencia, 4 May 2016).

As the rehearsals progressed, the perceived neutral aesthetic space of the project enabled Abir to step outside of her comfort zone. While some of the group’s repertoire was grounded in a more familiar Arab-Andalusian style, she soon moved beyond what she was used to, singing in flamenco-pop oriented songs that were a world apart from her training. Drawing on Brinner’s work, Goldstein (Citation2017: 53) argues that ‘the collaborative encounter can also spark musical growth and the expansion of musical competence, as musicians can potentially learn from one another and expand their own competences’. This expansion of competencies was certainly the end result of Abir’s own process of musical development throughout the collaboration. For Abir then, the experience of creation and dialogue engendered by the intercultural collaboration was, partly, an emancipatory one. The interspace between different musical and cultural traditions enabled here to expand her own worldview.

Sometimes, however, ICD instigates a clash of musical worldviews as individuals work through their relationships with each other and with their own traditions. Yoav, the guitarist for the project, is a particularly interesting example. At the end of the rehearsal process, he told me that he had felt like the ‘odd one out’, for two reasons. First, the organised format of the rehearsals was a departure from his usual compositional and ‘conceptual approach’ to music making (Goldstein Citation2017: 53). He is accustomed to being band leader and to engaging in improvisation around jazz idioms, allowing arrangements to emerge ‘organically’ through collaboration and experimentation. In Ziryab and Us, however, Yoav became a follower rather than a leader and he was working in a somewhat orchestrated context in which the rehearsals focused on the arrangement of existing compositions, with a lot of discussion and planning, rather than his usual preference to ‘let the music speak’. This was a conscious, and somewhat selfless, decision on Yoav’s part, because he felt that his normal modus operandi did not fit with how the other musicians worked. Second, as an Israeli jazz musician less aligned than the other musicians with the concept of a shared Arab-Andalusian heritage, Yoav was unfamiliar with the Ziryab trope that underpinned the project and, as a result, the default conceptual framework of musical commonality did not influence his own musical thinking.

Perhaps more so than the other musicians, however, Yoav treated the rehearsals as an opportunity to experiment with unfamiliar styles. Being that flamenco was one of the core traditions underpinning the project, Yoav tried to adapt his playing to suit a flamenco aesthetic, an endeavour that was in part spurned on by Sergio de Lope. Early on in the rehearsals, Yoav asked for a nylon-string guitar to play on rather than his jazz guitar in order to give the music the right ‘feel’. Sergio de Lope also encouraged Yoav to play in a manner that was identifiably flamenco, in terms of the placement of chords, rhythmic patterns, a harsh timbre and strumming techniques. This was particularly apparent in moments where Sergio was leading relatively traditional flamenco pieces in which he felt adherence to an identifiable flamenco aesthetic was particularly important. However, given the short time frame and complexities of flamenco guitar performance that take years to master, Yoav struggled to adapt his jazz style to the peculiarities of flamenco, and other members of the group felt that he needed to foreground more clearly his own musical training as a jazz guitarist rather than attempting to mimic a style with which he had no direct experience.

The point I wish to make here is that the relational processes that characterised this intercultural project were not determined exclusively by cultural parameters but began with the individuals’ own relationships with traditional practice and the competencies needed to navigate the interspace between different musical worldviews. Indeed, as Barrett has pointed out, ICD requires the development of particular skills, such as ‘open-mindedness, empathy, multiperspectivity, cognitive flexibility, communicative awareness, the ability to adapt one’s behaviour to new cultural contexts, and linguistic, sociolinguistic and discourse skills including skills in managing breakdowns in communication’ (Barrett Citation2013: 26; Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2020: 12). The seemingly neutral artistic space of the project enabled the musicians to expand their sense of musical self, the relationship with their own traditions and the skills necessary to navigate at times quite disjunct musical competencies. Yet the results of these negotiations were not clear cut. Early on in the rehearsals, some members of the group, and particularly Virginia, felt that Abir was too grounded in her classical training and thus encouraged her to expand her musical horizons. Yet Yoav, keen to experiment with other styles, was actually encouraged by some members of the group to return to his comfort zone and bring forward to the group something of himself.

In Search of a ‘Common Musical Language’

As well as a metaphor for revisiting one’s relationship with tradition, Virginia also saw the Ziryab and Us title as a discursive framework for ICD through which she encouraged the group to search for a common language. As Brinner notes, musicians in collaborative projects such as this often reject the term ‘fusion’, but rather seek the creation of a ‘new musical language’ (Brinner Citation2009: 124; Bayley and Dutiro Citation2016: 395). It is this idea of a common language that underpins much of the discourse surrounding the musical legacies of al-Andalus. In returning to the framework of ICD, it is worth considering Cantle’s (Citation2012) understanding of interculturalism as the synthesis of shared cultural values and dialogue. Through the process of ICD, the musicians in Ziryab and Us sought to retrieve the ideals of an allegedly shared Mediterranean past (through the myth of Ziryab) as the basis for ICD in the creation of something new. However, the search for a common language was far from easy and the residency raised a number of questions: what was the basis for this common language and which traditions were foregrounded? What aesthetic issues mediated the collaborative process? In this section, I consider the relational processes that emerged across genres, as the musicians sought to establish a cohesive musical identity within a very short space of time.

Repertoire Choices and the Flamenco-Andalusí Nexus

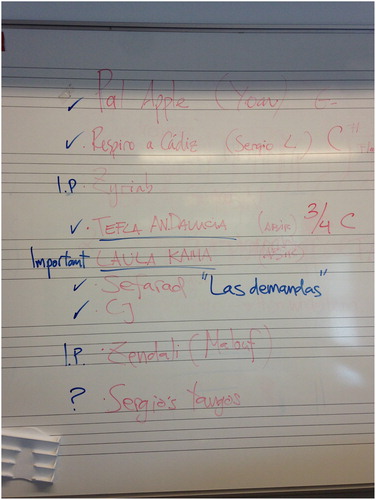

It is worth reflecting on the group’s repertoire choices to understand better the rocky path towards a common musical language. In an attempt to represent the diversity of training and perceived musical connections across the Mediterranean, there were a number of styles that made an appearance. This included genres that allegedly trace their lineage to al-Andalus most notably Arab-Andalusian music (from across different maghrebi traditions, but with particular emphasis on the Moroccan al-âla repertoire due to Abir’s own training) and flamenco, but also chaabiFootnote7 and Sephardi romances; and genres that fell outside of the Andalusí legacy such as gnawa, jazz, pop and European folk music. One of the most difficult parts of the rehearsal process that caused the most friction between the musicians was settling on a repertoire list that best represented the collective identity of the group. Given that the musicians only had six days to put together a complete concert to be held at Casa Árabe in Madrid, they ended up creating arrangements of existing compositions rather than new pieces, even though some people in the group felt the only way to really cement a unique group identity was to create a composition from scratch. The final repertoire list ended up with a combination of existing compositions by the individual musicians arranged for the whole group and arrangements of pieces from traditional repertoires (). The rehearsal process was fascinating to observe as the musicians combined notation, improvisation and learning from YouTube examples and recordings in the creation of a programme ready for the concert ().

Figure 2. The repertoire list during the rehearsals. Photo taken by the author, Valencia, 4 May 2016.

Although the musicians tried to balance a diverse range of genres, it became apparent that the arrangements gravitated towards the fusion between flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music as the base denominator for the collaboration. Ziryab is often viewed as the ‘founding father’ of flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music (the so-called sons of Ziryab), and many musicians refer to these two genres as ‘sisters’ that possess the same genealogical root and allegedly stylistic similarities. As a result of this notion of musical commonality, since Spain’s transition to democracy in the 1980s numerous Spanish and Moroccan musicians have sought to bring flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music into dialogue in what is often described by musicians as a sonic reconciliation of history. Such a narrative of musical commonality functions as a powerful rhetorical device in the promotion of convivial relations between Spaniards and Moroccans, particularly in the context of the social integration of Moroccan communities in Andalusia.Footnote8 The piece that perhaps best illustrates this type of fusion was a medley based on Salim Halali’s (1920–2005) song ‘Andaloussia’. Salim Halali was a Jewish Algerian Arab-Andalusian singer who arrived in France in the late 1930s and became an icon of the French-Arab café and cabaret scene. Hisham Aidi (Citation2014: 263) argues that ‘it was in these cafés that the French-Cabaret sound was born as […] Halali, and others, mixed the sounds of interwar Paris–big band, rumba, bolero, tango, flamenco–with their Andalusian training’. Halali became well-known throughout France and the Maghreb for performing light flamenco styles (such as sevillanas) in Arabic. Moreover, given his multiple identities as a gay Jewish Arab who performed a range of musical styles rooted in the mythology of al-Andalus, Halali is often upheld today as a ‘symbol of convivencia’ (Aidi Citation2014: 319).Footnote9 Given the symbolism surrounding Halali, it is not surprising then that the Ziryab and Us group chose his most famous track ‘Andaloussia’.Footnote10 The song was brought to the group by Abir and the other musicians listened intently via YouTube multiple times as they gradually worked out their own version. Eventually, the musicians settled on a lengthy medley incorporating Halali’s song, a flamenco fandango melody and tanguillos, and a Moroccan chaabi piece by the composer Abdessadaq Chekara (1931–1998).

The notion of a shared musical history between flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music also characterised the interpersonal relations between Sergio de Lope and Abir. In the absence of linguistic affinities, the notion of musical affinity frequently emerged in the interactions between these two musicians. Throughout the week spent with the group, I witnessed numerous ‘sing offs’ between the two musicians both inside and outside of the rehearsals, where they traded melodies that circulated the Strait of Gibraltar and conflated musical styles. Abir boldly stated on more than one occasion that ‘Spanish and Moroccan music are the same, they come from the same root’ (personal communication, Valencia, 2 May 2016). At one point during the rehearsals when Abir was improvising a florid, ornamented melody, Sergio responded ‘olé, Marchena!’. Olé is the term a flamenco artist or aficionado would use to demonstrate satisfaction with a particular performance, a codified response to a musical flourish that is deemed aesthetically pleasing. With Marchena, Sergio was referring to the flamenco singer Pepe Marchena (1903–1976) who was renowned for his highly ornamented vocal style and which Sergio heard in Abir’s own vocal style.

It was these spontaneous performances of musical affinity that reinforced the flamenco/Arab-Andalusian nexus as central to the project. What was most striking in the musical interactions between Abir and Sergio was how they translated across musical systems. For example, Sergio would conceive of Abir’s chaabi rhythm (itself derived from the driving rhythmic patterns most often associated with gnawa) as a flamenco tanguillos; he was able to make an unfamiliar musical structure feel familiar by ‘correcting’ the rhythmic pattern ‘to fit [his] existing acculturated schemata or categories’ (Stobart Citation2013: 129).Footnote11 Such acts of musical translation are common in intercultural collaborative projects, as musicians make sense of unfamiliar styles according to their own musical experience, a process of communication and the formation of musical choices based on extant knowledge that Feld refers to as ‘interpretive moves’ (Feld Citation2005. Also see Bayley Citation2011: 401–404).

The key point here though is that, while we may be able to account for these acts of translations as a process of cognitive consonance and the adaptation of unfamiliar musical structures to suit familiar modes of ‘cultural hearing’ (Stobart Citation2013), the musical translations between Serio and Abir were, to cite Cook again, ‘situated encounters’. Their musical interactions were anchored in the idea of a shared genealogy between flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music, an idea that became a ‘way of relating’ both musically and personally (Goldstein Citation2017: 102). Moreover, given the discursive framing of the project around the myth of Ziryab, a figure so intrinsic to the origin narratives of flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music, it was logical that Abir and Sergio’s musical relations both inside and outside the rehearsals would become the base denominator for the whole project. Ultimately, what is significant here is how the intertwining of discourse and musical practice actually structured the interpersonal (musical) relations between two individuals who were unable to relate to each other, in any great depth, at a linguistic level. And, the emergence of flamenco/Arab-Andalusian music as the base denominator was not so much a conscious decision, but a consequence of the symbolic ‘anchoring’ of Ziryab, the project’s focus on revisiting the Arab-Andalusian legacy and the interactions between Abir and Sergio.

Reinventing Ziryab: Breaking the Mould

The centrality of the flamenco/Arab-Andalusian nexus was, however, challenged throughout the project. Virginia and Colin, in particular, suggested that the group should try to break free of the stereotypical associations grounded in the Arab-Andalusian legacy of Ziryab. They wanted to modernise Ziryab, to bring him into dialogue with the twenty-first century and with a broader range of musical practices. Indeed, an integral part of the value system underpinning ICD is ‘a critique of the essentialist notions of identity: intercultural dialogue is described as stipulating and fostering identities as transforming, plural, and fluid’ (Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2020: 12), which was evident in Ziryab and Us. As a result of group conversations, the musicians sought to overcome the dominance of flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music in the project in order to create a more equal basis for the different genres that constituted the intercultural encounter.

One way this was achieved was by fully incorporating jazz harmonic frameworks and rhythmic sensibilities into the project. While Colin Heller brought a unique melodic twist to the group drawing from central European folk music and classical violin, it was Yoav who was central in reframing the boundaries of the group’s direction given that he provided the harmonic, and to a certain extent, rhythmic grounding. As discussed in the previous section, Yoav experimented with flamenco guitar playing particularly with some pressure from Sergio de Lope. However, when it became clear that flamenco was beginning to dominate and that Yoav was not getting the chance to foreground his own musical personality, the group sought to address this imbalance of styles. Virginia said that she was offered a flamenco guitarist for the project, but she wanted to take a different direction hence the inclusion of Yoav as a jazz guitarist. Even Abir herself (despite personally and culturally invested in the narrative of musical commonality between flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music) said ‘I want to hear jazz, jazz – flamenco, andalusí and jazz. Everyone does just flamenco-andalusí’ (group conversation, Valencia, 5 May 2016). From this point, there was a marked shift in Yoav’s playing, where jazz harmonic progressions and guitaristic techniques became a more fundamental structural element of the project rather than simply a flavour.

However, the search for a common musical language that could offer a fresh interpretation of a well-worn legend did not lie entirely within the control of the group. The Berklee College of Music as an institution also had a bearing on the group’s collaborative efforts. Twinned with the Berklee College in Boston, Massachusetts, the Valencia campus offers programmes in popular music performance, music production and the global music business. Present at the residency was the artistic director, Javier Limón, a well-known Spanish producer who has worked with internationally renowned flamenco musicians such as Paco de Lucía. As part of the residency, Ziryab and Us had the opportunity to record two tracks with Javier: the ‘Andaloussia’ track and another track with students at Berklee. For the latter, they chose a piece by Sergio Martínez called CJ, which was a flamenco-pop oriented composition based on a bulería rhythm,Footnote12 with elements of a conventional pop song structure (for example, melodic hook, verse, chorus) and with English lyrics.Footnote13 In conversation with the group prior to the recording, Javier encouraged the musicians to ‘think of this recording as something that can be really big, so we can present the project to Universal or to a record company, have all that in mind. We are not only [making] a recording in Berklee for the Medinea project, we really can do something important and big’ (group conversation, Valencia, 4 May 2016). Throughout the recording session, Javier’s vision as a producer and the musical exchanges with the students thrust the Ziryab and Us project (and the discourse of Ziryab itself) into a very different aesthetic domain grounded in the commercial parameters of the world music industry. Therefore, the search for a common musical language around which the project could coalesce was not simply a case of threading together the divergent competencies of the group, but was also nuanced by the Berklee institution through Javier Limon’s own commercial vision for what constituted a successful world music project.

Macro-Social Influences on Ziryab and Us

I have thus far focused on the micro-social relational processes that emerged in the rehearsals, exploring how the musicians navigated their own individual musical identities vis-à-vis tradition and the search for a common musical language. However, by focusing too heavily on the minutiae of the rehearsals, it is easy to miss the wider contextual issues that may influence such intercultural encounters. I wish to move my analysis from the micro-social domain of interaction, interpersonal relations and human agency, and towards a consideration of how the musicians’ artistic choices were nuanced by wider historical and political factors. I argue that such a macro-social approach is particularly important in projects such as Ziryab and Us that are ostensibly packaged as purely artistic and apolitical in nature. Virginia was eager to stress to me the apolitical nature of the project, keenly aware of the ways in which music is politicised in the region. Yet, no project of intercultural dialogue, however ‘artistic’ and neutral its aims may be, emerges in a vacuum.

At one level, (post)colonial relations between Morocco and Spain lay in the background of the collaborative process. The fact that musical commonalities between flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music became the base denominator has a historical precedent that deserves mention. The very idea of a shared heritage between flamenco and Arab-Andalusian music is intertwined with the legacies of Spanish colonialism in Morocco (1912–1956). In an attempt to foster a so-called Spanish-Moroccan ‘brotherhood’ and to legitimise colonial rule, the Spanish drew cultural capital from the alleged links between these musical styles to promote the idea of a more benevolent form of colonialism. According to Eric Calderwood (Citation2018: 230–250), the Spanish believed they had a genealogical right to study and ‘speak for’ Moroccan Arab-Andalusian music given its roots in medieval Spain, and that Moroccans needed the Spanish to preserve a tradition that, in Spanish eyes, had fallen into decay under Moroccan patronage. Moreover, flamenco, like Arab-Andalusian music, was seen as an offspring of the cultural interactions between different religious and ethnic communities that allegedly took place both during and following Muslim occupancy in the Iberian Peninsula.

This perceived shared sonic imaginary rooted in the colonial encounter has echoes in the present. Given the high levels of Moroccan immigration in Southern Spain since the 1980s, the idea of a shared musical history is harnessed by Spanish cultural and governmental institutions to promote the social integration of immigrants and cultural diplomacy with Morocco.Footnote14 While the capacity for such institutional projects to promote integration and actually overcome unequal power relations is questionable, intercultural musical encounters do present one way in which Spaniards and Moroccans might foster mutual understanding and cultural interaction (Machin-Autenrieth Citation2020). Abir and Sergio’s frequent allusions to musical affinity discussed above might be read, therefore, as the playing out of these colonial and postcolonial relations. Given the Ziryab myth’s rootedness in a Spanish-Moroccan shared musical imaginary, the project gravitated towards the flamenco/Arab-Andalusian nexus as the default basis for the collaboration. And this nexus was a musical realisation of the historical and cultural connections between Spain and Morocco, which framed the personal and artistic relationship between Abir and Sergio. Individual and interpersonal agency, in this respect, is imprinted with the wider legacy of international relations across the Strait of Gibraltar. Inverting Stobart’s (Citation2013: 131) statement that ‘a range of social processes, including class, race, gender, ideology, politics and economics, or the presupposition of difference, often contribute to rendering certain musics unfamiliar’, it is precisely the socio-historical and political convergences and encounters that characterise Spanish-Moroccan relations that contributed to a sense of musical familiarity rather than unfamiliarity in the Ziryab and Us project.

Mediterraneanism

The project was also underpinned by a wider sense of Mediterraneanism beyond just Spanish-Moroccan relations. Here, I find it useful to reflect on the work of Christian Bromberger who characterises the Mediterranean as a highly complex region of confluence, exchange, tension and conflict. He presents three ‘images’ of the Mediterranean: one of coexistence and commonality; one of conflict and hatred; and one of a ‘system of complementary differences’ (Bromberger Citation2007). In the context of Ziryab and Us, it is the first image that is perhaps most prevalent – the ICD at the centre of the project was predicated on the wider notion of cultural affinity and dialogue across the Mediterranean. As Bromberger (Citation2007: 293) notes, ‘Out of this Mediterranean of tolerant coexistences, of meetings, of the interpenetration of cultural works, there emerge some emblematic personal figures who have been naturally seized upon by the pioneers of the dialogues of civilization’. Ziryab might be understood as one such individual – a quasi-mythical figure who threads together a complex patchwork of interrelated, yet disjunct, Mediterranean musical styles and cultural identities.

As Goffredo Plastino (Citation2003: 10) argues ‘it is through its music that the Mediterranean is continually and variously defined and defines itself’. Music provides a space for a sort of conceptual unity; it enables a number of diversities to coexist through the ‘spirit’ of Mediterranean-ness. This concept of Mediterranean unity was particularly apparent in how Ziryab and Us was promoted, where there was emphasis on the circulation and integration of musical styles from across the basin. Most significant in this respect was the broader institutional structure for the project in terms of the Medinea network that supported the residency. The Medinea’s mission statement is to support ‘the professional integration of young Mediterranean musicians, by developing intercultural projects that enhance dialogue, transmission, and mobility around the Mediterranean basin’.Footnote15 Medinea was founded in 2014 through the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence and consists of a network of cultural organisations from across the region that host a range of intercultural ‘creation sessions’ (residencies and workshops). The network also functions as a promotional agency for young up-coming artists from the Mediterranean, of which Colin Heller is one such artist. Funded through the European Union, the network states that the tackling of contemporary challenges in the Euro-Mediterranean region (such as, interreligious relations and social integration) through acts of ICD is one of its fundamental goals. Music is promoted as a tool to move beyond linguistic and cultural barriers, and echoing Plastino’s notion of a Mediterranean ‘spirit’, the network contends that Mediterranean musical heritage ‘has been shaped over the centuries thanks to permanent interaction and re-appropriation of various artistic traditions, demonstrating richness and diversity which must be made known, highlighted, and renewed’.Footnote16

The institutional goals of the Medinea network found a musical corollary in the Ziryab and Us project given the diversity of the repertoire and the language of commonality and dialogue used in the project’s promotional material and by the musicians themselves. But the notion of Mediterranean unity can only go so far. Plastino (Citation2003: 17) argues that Mediterraneanism is sometimes employed as an arbitrary label, and that any sense of geographical and cultural unity quickly falls apart when divergent genres are brought together. While it would be churlish to call the project’s embracement of Mediterraneanism as ‘arbitrary’, the difficulty the group had in reconciling musical worldviews as described above does underscore the fragility of Mediterraneanism as a unified cultural concept.

What was most striking though was the political tensions that emerged at points during the rehearsals, which reflected wider societal tensions across the Mediterranean. As Bromberger (Citation2007) highlights, the ideals of unity and commonality clash against the ‘cacophony’ of the Mediterranean. A Mediterranean that is ‘face-to-face rather than […] side-by-side’ (Bromberger Citation2007: 294).

When I first met Virginia, we were discussing the wider ramifications of the project particularly in relation to the context of Arab-Israeli relations and the overcoming of religious animosity. I asked whether she felt the project had any political implications, drawing parallels with the West-Eastern Divan orchestra and Israeli-Palestinian musical collaborations.Footnote17 She insisted that Ziryab and Us had no political agenda whatsoever, instead viewing it as an aesthetic journey; an apolitical and intercultural space for individuals to collaborate and grow as musicians. However, despite Virginia’s best efforts, the project was still influenced by wider societal issues and, as a result, her belief in intercultural dialogue as an apolitical, aesthetic enterprise was called into question. For example, early on in the rehearsals, the musicians were discussing possible repertoire choices. Abir suggested to perform a piece that she knew with lyrics in both Arabic and Hebrew, to which Yoav expressed reservations. Surprised by his response, the group pushed him as to why he did not want to perform it. It transpired that he was fearful that Casa Árabe, the cultural organisation hosting the concert in Madrid, would not welcome a song with lyrics in Hebrew. As an Israeli, he was even nervous to perform in the venue and make his identity explicitly known. The rest of the group was surprised by his comments, because they felt that the project’s essence was to cross religious and linguistic divides.

However, Yoav’s concerns were not entirely unfounded. Created in 2006, Casa Árabe operates as a strategic centre for Spanish relations with the Arab world, engaging in public diplomacy through business, politics, academia, education, the arts and heritage. Spain’s leading pro-Israeli organisation and lobby group, Acción y Comunicación sobre Medio Oriente [Action and Communication about the Middle East], has accused Casa Árabe of possessing an anti-Israel agenda and a biased, unilateral vision of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.Footnote18 Medinea, as well, opposes collaboration with Israeli institutions while stressing that it does collaborate with individual Israeli musicians. As the only Israeli musician, Yoav, perhaps more than the other musicians, was sensitive to the potential political reverberations of Ziryab and Us even if the other musicians lauded its ability to overcome barriers and to promote dialogue. The group did not end up performing the Hebrew-Arabic song that Abir had suggested. This was just one of a number of seemingly aesthetic decisions that had wider political reverberations, illustrating what happens when the discourse of intercultural apoliticism collides with political realities. Even when Ziryab and Us was framed as a purely creative, apolitical project, existing fractures across the Mediterranean still nuanced how the musicians related to each other artistically and personally. As Bromberger (Citation2007: 299) contends, ‘Everyone is defined, here [the Mediterranean] perhaps more than elsewhere, in a game of mirrors (customs, behaviours, affiliations) with his neighbour. This neighbour is a close relation who shares Abrahamic origins and his behaviour only makes sense in this relational game’.

Conclusion

As Cook (Citation2012: 206) reminds us ‘all intercultural perceptions are bilateral – intercultural analysis is always situated, always a performative transaction, always replete with meaning’. He encourages us ‘to move musical encounters, of whatever nature, to the centre of musicological explanation, emphasizing how they embody the specific actions, judgements and choices of human agents, and how those are afforded but not determined by the specific circumstances within which people act, judge and choose’ (Cook Citation2012: 194). In so doing, he advocates for a relational approach that in effect balances out the micro and macro forces that influence the creative choices made by individual musicians. In this article, I too have sought to bring the musical encounter into the centre of my analysis and to balance micro and macro readings of an intercultural collaborative project. I have explored how musicians from divergent backgrounds engaged in intercultural music making with a focus on three relational processes: the individuals’ own relationship with tradition, the search for musical commonality across styles and the macro-social factors (institutional, historical, political) that influenced the collaborative process.

In the Ziryab and Us project, the myth of Ziryab provided a discursive framework for intercultural dialogue built on the concept of a shared musical space. However, as the project’s subtitle boldly states, this was a ‘new vision’ for the Arab-Andalusian legacy: one that sought to offer an innovative, modern interpretation of a well-worn legend. Ziryab and Us was also intended as an apolitical, intercultural collaboration – one that emphasised individual creativity and development, and the bringing together of distinct musical styles into a common language. However, various points of tension emerged during the rehearsals that inhibited the journey towards a common musical language – if it was ever reached at all. Following the 2016 residency, the group participated in a handful of other events including another residency, an outreach project and concerts. Since 2017, however, the group has been inactive, and, to the best of my knowledge, the musicians have no plans to continue with the project. Why, then, has the Ziryab and Us project not continued? At one level, there were numerous logistical issues: Virginia Pisano has since moved into academia; the geographical spread of the musicians makes it difficult to rehearse; and the musicians have their own individual projects that require huge investment in terms of time and creative energy. While it was hoped the project would continue, in the end geography and logistics have been major factors in preventing its continuation.

At another level, I believe that Ziryab and Us is reflective of the problems that are inherent in some projects of intercultural dialogue. As Bayley and Dutiro (Citation2016: 399–400) note, ‘There are two ways in which collaboration fails to work properly: (1) when the emphasis is placed on an end product for promotional purposes and commercial gain; and […] (2) when the relationship is immediately directive rather than collaborative and means dialogue cannot take place’. The project thrust musicians from divergent musical backgrounds into a rehearsal context that was largely manufactured. While not directly for commercial gain, emphasis was placed on an ‘end product’ (the concert at Casa Árabe and recording at Berklee). Moreover, the project was underpinned by a loose and deterministic discursive framework (that is, Ziryab and the Arab-Andalusian legacy) that favoured the fusion of certain styles over others. Therefore, it was difficult for the musicians to build a cohesive repertoire that could speak to the broader vision of Mediterranean unity and the musicians’ divergent backgrounds. Perhaps most significantly, the project was underpinned by a directive institutional agenda (through Medinea) that set the terms of reference – an institutional agenda that promotes intercultural dialogue and diversity across the Mediterranean as an apolitical enterprise, even if the institution itself is guided by political strategies around diversity and community cohesion.

For Virginia and the musicians, the project was envisioned as an opportunity for creative engagement and innovation that, while rooted in an image of Mediterranean unity and ‘polyphony’ (to cite Bromberger Citation2007), was an apolitical project built on the ideals of music’s universality. However, the interactions between the musicians and the institutional framework of the project cannot be divorced from wider historical and political factors that underpinned and, at times, undermined the vision of intercultural dialogue as an apolitical enterprise. The points of commonality (imagined or otherwise) that threaded together the project were pushed and pulled in different directions, illustrating the relational game of mirrors that often plays out in the Mediterranean (Bromberger Citation2007). Ultimately, as Shannon (Citation2015: 29) notes, Ziryab is ‘good to think’: a figure of thought that occupies an uneasy space between discourse and practice; a historical, musical utopia that, when brought into the context of intercultural dialogue in the present, cannot quite become a musical reality.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the researchers on my ERC team (Samuel Llano, Stephen Wilford and Vanessa Paloma Elbaz) and Amanda Bayley for their thoughts and comments on a draft version of this article. Most importantly, I extend my gratitude to Virginia Pisano, Javier Limón and all the members of Ziryab and Us for allowing me to observe rehearsals and spend time within them throughout the residency. Finally, I thank the anonymous reviewers for their in-depth feedback on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew Machin-Autenrieth

Dr. Matthew Machin-Autenrieth is Lecturer in Ethnomusicology at the Department of Music, University of Aberdeen and the Principal Investigator for the European Research Council funded project ‘Past and Present Musical Encounters across the Strait of Gibraltar’ (2018–23). He is also a Visiting Research Fellow at the Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge (until 2023). Matthew completed his Masters and PhD in Ethnomusicology at Cardiff University. Following his studies, Matthew was appointed as a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Cambridge (2014–17) and then Senior Research Associate (2018-20).

Notes

1 Medinea will be discussed in more detail below. See https://medinea-community.com [accessed 14 September 2020].

2 My methodology was influenced by Amanda Bayley’s (Citation2011) ethnographic analysis of a contemporary string quartet rehearsal where she also focused on the micro-social relations and decision-making processes in a collaborative context. It is important to note that this research only focuses on the creative process and ethnography with the musicians, it does not consider audience reception.

3 Such an approach to interculturalism is often positioned as a counterpoint to the perceived failings of multiculturalism.The emphasis on the dialogue between cultures has been adopted by national and European institutions as a more suitable framework for the social integration of minority communities than multiculturalism, as the latter tends to favour the preservation and protection of discrete cultural identities and practices. For a wider discussion of the politics of interculturalism in the musical context, see Conversi and Machin-Autenrieth (Citation2020).

4 For more information on the standard narrative of Ziryab see Reynolds (Citation2008) and Shannon (Citation2015: 38–40).

5 The term nūba (pl. nūbāt) is used to refer to suites in Arab-Andalusian music, consisting of a combination of different vocal and instrumental sections with varying rhythms that are grouped according to mode. It is important to note that these suites differ across national boundaries (for example, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia) and across different musical traditions (for example, garnati, ma’aluf). For a description of the nūbāt in the Moroccan context (as pertaining to the al-âla tradition), see Davila (Citation2013: 7–9).

6 Sergio Martínez became the de facto group leader. This was not decided upon, but his role seemed to develop naturally out of the interactions in the group. This was probably due to his position as a teacher at Berklee, his amiable personality and his fluent English and Spanish which enabled him to translate between some of the group members.

7 Chaabi literally means ‘of the people’ or ‘popular’ and so, in a musical context, is often used across the Maghreb and Middle East to refer loosely to ‘popular music’ encompassing a range of different styles. In the Ziryab and Us project, Abir in particular drew on Moroccan chaabi music, a collection of popular styles that cross Arab, Andalusí and Amazigh influences with both rural and urban derivations. She is particularly influenced by the chaabi performances of prolific figures such as Abdessadeq Chekara (1931–1998) and the pioneering chaabi group from the 1970s, Nass el-Ghiwane (Simour Citation2016).

8 Elsewhere I have written about intercultural music making in the context of Moroccan migration (Machin-Autenrieth Citation2019, Citation2020). Also see the work of Ian Goldstein (Citation2017); Brian Karl (Citation2015); Brian Oberlander (Citation2017); and Jonathan Shannon (Citation2015) who explore similar issues around Spanish-Moroccan musical exchange, the narrative of a shared cultural history and Moroccan migration.

9 Convivencia (coexistence) is the term used to refer to the alleged peaceful coexistence and exchange between Christians, Jews and Muslims in al-Andalus. While the term has been roundly deconstructed at a historical level, it is often employed today to promote interreligious tolerance and exchange. For a useful introduction to the history of convivencia as an idea and its contemporary usages see: Aidi (Citation2005); Akasoy (Citation2010); Anidjar (Citation2006); Baxter Wolf (Citation2009); Doubleday and Coleman (Citation2008); and Hirschkind (Citation2014).

10 There has been something of a resurgence in popularity of Halali’s recordings, particularly given his appearance in the popular French film, Les Hommes Libres. For more information on Halali and his appearance in the film, see Aidi (Citation2014: 260–264, 293–294, 318–323).

11 Goldstein (Citation2017: 71) also notes that the tanguillos-chaabi connection is a common point of reference between flamenco and Arab-Andalusian musicians. For an example of a tanguillos rhythm see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Acher5B5-Kk, and for a chaabi rhythm see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8CS8C9aUczA [accessed 27 August 2019].

12 The bulería rhythm is characterised by a twelve-beat cycle that is based on a hemiola (3/4 against 6/8 time).

13 A recording of CJ can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KFplrSfCslY [accessed 14 September 2020].

14 See Conversi and Machin-Autenrieth (Citation2020); and Machin-Autenrieth (Citation2020).

15 https://medinea-community.com/the-network/ [accessed 26 August 2020].

16 https://medinea-community.com/manifesto/ [accessed 26 August 2020].

17 For a critical analysis of the West-Eastern Divan orchestra see Beckles Willson (Citation2009a, Citation2009b). For a rich ethnographic account of Israeli-Palestinian collaborative projects, see Brinner (Citation2009).

18 For more information, see the report ‘Casa Árabe, the think tank of Spanish public institutions against Israel’ http://a-com.es/spanish-institutions-against-israel/ [accessed 26 August 2020].

References

- Aidi, H., 2005. The Interference of al-Andalus: Spain, Islam and the West. Social Text, 24 (2), 67–88.

- Aidi, H., 2014. Rebel Music: Race, Empire and the New Muslim Youth Culture. New York: Vintage Books.

- Akasoy, A., 2010. Convivencia and Its Discontents: Interfaith Life in al-Andalus. International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 42, 489–499.

- Anidjar, G., 2006. Futures of al-Andalus. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, 7 (3), 225–239.

- Balosso-Bardin, C., 2018. #No Borders. Världens Band: Creating and Performing Music across Borders. The World of Music, 7 (1–2), 81–106.

- Barrett, M., 2013. Introduction: Interculturalism and Multiculturalism: Concepts and Controversies. In: M. Barrett and M. Barrett, eds. Interculturalism and Multiculturalism: Similarities and Differences. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 15–42.

- Baxter Wolf, K., 2009. Convivencia in Medieval Spain: A Brief History of an Idea. Religion Compass, 3 (1), 72–85.

- Bayley, A., 2011. Ethnographic Research into Contemporary String Quartet Rehearsal. Ethnomusicology Forum, 20 (3), 385–411.

- Bayley, A. and Dutiro, C., 2016. Developing Dialogues in Intercultural Music-Making. In: P. Burnard, E. Mackinlay, and K. Powell, eds. The Routledge International Handbook of Intercultural Arts Research. Abingdon: Routledge, 391–403.

- Beckles Willson, R., 2009a. The Parallax Worlds of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 134 (2), 319–347.

- Beckles Willson, R., 2009b. Whose Utopia? Perspectives on the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. Music and Politics, 3 (2). Available from: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mp/9460447.0003.201/–whose-utopia-perspectives-on-the-west-eastern-divan?rgn=main;view=fulltext [Accessed 18 July 2019].

- Brinner, B., 2009. Playing Across a Divide: Israeli-Palestinian Musical Encounters. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bromberger, C., 2007. Bridge, Wall, Mirror; Coexistence and Confrontations in the Mediterranean World. History and Anthropology, 18 (3), 291–307.

- Calderwood, E., 2018. Colonial al-Andalus: Spain and the Making of Modern Moroccan Culture. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Cantle, T., 2012. Interculturalism: The New Era of Cohesion and Diversity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cook, N., 2012. Anatomy of the Encounter: Intercultural Analysis as Relational Musicology. In: S. Hawkins, ed. Critical Musicological Reflections: Essays in Honour of Derek B. Scott. Aldershot: Ashgate, 193–208.

- Conversi, D., and Machin-Autenrieth, M., 2020. The Musical Bridge: Intercultural Regionalism and the Immigration Challenge in Contemporary Andalusia. Genealogy, 4 (5). https://www.mdpi.com/2313-5778/4/1/5.

- Davila, C., 2013. The Andalusian Music of Morocco: History, Society and Text. Wiesbaden: Reichart.

- Doubleday, S. and Coleman, D., eds, 2008. In Light of Medieval Spain: Islam, the West and the Relevance of the Past. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Feld, S., 2005. Communication, Music and Speech about Music. In: C. Keil, and S. Feld, eds. Music Grooves. 2nd ed. Tucson, AZ: Fenestra Books, 77–95.

- Goldstein, I., 2017. Experiencing Musical Connection: Sonic Interventions in Mediterranean Social Memory. PhD Diss., University of California, Berkeley.

- Hirschkind, C., 2014. The Contemporary Afterlife of Moorish Spain. In: N. Gole, ed. Islam and Public Controversy in Europe. Farnham: Ashgate, 227–240.

- Karl, B., 2015. Across a Divide: Cosmopolitanism, Genre and Crossover among Immigrant Moroccan Musicians in Contemporary Andalusia. Migration Studies, 3 (1), 111–130.

- Lähdesmäki, T., Koistinen, A.K., and Ylönen, S.C., 2020. Introduction: What Is Intercultural Dialogue and Why Is It Needed in Europe Today. In: T. Lähdesmäki, A.K. Koistinen, and S.C. Ylönen, eds. Intercultural Dialogue in the European Education Policies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–20.

- Machin-Autenrieth, M., 2019. Spanish Musical Responses to Moroccan Immigration and the Cultural Memory of al-Andalus. Twentieth-Century Music, 16 (2): 259–287.

- Machin-Autenrieth, M., 2020. The Dynamics of Intercultural Music Making in Granada: ‘Everyday’ Multiculturalism and Moroccan Integration. Ethnomusicology, 64 (3), 422–446.

- Oberlander, B., 2017. Deep Encounters: The Practice and Politics of Flamenco-Arab Fusion in Andalusia. PhD Diss. Northwestern University, Illinois.

- Plastino, G., 2003. Introduction: Sailing the Mediterranean Musics. In: G. Plastino, ed. Mediterranean Mosaic: Popular Music and Global Sounds. New York: Routledge, 1–36.

- Reynolds, D., 2008. Al-Maqqarī’s Ziryab: The Making of a Myth. Middle Eastern Literatures, 11 (2), 155–168.

- Shannon, J.H., 2015. Performing al-Andalus: Music and Nostalgia across the Mediterranean. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Simour, L., 2016. Larbi Batma, Nass el-Ghiwane and Postcolonial Music in Morocco. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

- Stobart, H., 2013. Unfamiliar Sounds? Approaches to Intercultural Interaction in the World’s Musics. In: E. King and H. Prior, eds. Music and Familiarity: Listening, Musicology and Performance. Farnham: Ashgate, 109–136.

- Ziryab and Us, 2016. Ziryab and Us: A New Vision of the Arab-Andalusian Heritage. Valencia: Promotional Booklet.